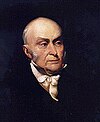

John Quincy Adams

John Quincy Adams (July 11, 1767 – February 23, 1848) was the sixth President of the United States from March 4, 1825, to March 4, 1829. He was also an American diplomat and served in both the Senate and House of Representatives. He was a member of the Federalist, Democratic-Republican, National Republican, and later Anti-Masonic and Whig parties. Adams was the son of President John Adams and his wife Abigail Adams. He and his father were the only Presidents in the first fifty years of the presidency to serve only one term.[2][pn 1]

As a diplomat, Adams was involved in many international negotiations, and helped formulate the Monroe Doctrine as Secretary of State. Historians agree he was one of the great diplomats in American history.[3]

As president he proposed a program of modernization and educational advancement, but was stymied by Congress, controlled by his enemies. Adams lost his 1828 bid for re-election to Andrew Jackson. In doing so, Adams became the first President since his father to serve a single term. As president Adams presented a vision of national greatness resting on economic growth and a strong federal government, but his presidency was not a success as he lacked political adroitness, popularity or a network of supporters, and ran afoul of politicians eager to undercut him.

Adams is best known as a diplomat who shaped American's foreign policy in line with his deeply conservative and ardently nationalist commitment to America's republican values. More recently he has been portrayed as the exemplar and moral leader in an era of modernization when new technologies and networks of infrastructure and communication brought to the people messages of religious revival, social reform, and party politics, as well as moving goods, money and people ever more rapidly and efficiently.[4]

Adams was elected a U.S. Representative from Massachusetts after leaving office, the only president ever to do so, serving for the last 17 years of his life. In the House he became a leading opponent of the Slave Power and argued that if a civil war ever broke out the president could abolish slavery by using his war powers, which Abraham Lincoln partially did during the American Civil War in the 1863 Emancipation Proclamation. Deeply troubled by slavery, Adams correctly predicted the dissolution of the Union on the issue, though the series of bloody slave insurrections he foresaw never came to pass.

Early life

Adams was born to John Adams and his wife [5] Abigail Adams in what is now Quincy, Massachusetts. Quincy in 1767 was the "north precinct" of Braintree, Massachusetts; Quincy became incorporated as an independent town in 1792 and was named for John Quincy, just as John Quincy Adams had been. The John Quincy Adams Birthplace is now part of Adams National Historical Park and open to the public. It is near Abigail Adams Cairn, marking the site from which Adams witnessed the Battle of Bunker Hill at age seven.

In 1779 Adams began a diary that he kept until just before his death in 1848.[6]

Adams first learned of the Declaration of Independence from the letters his father wrote his mother from the Second Continental Congress in Philadelphia.

Much of Adams' youth was spent accompanying his father overseas. John Adams served as an American envoy to France from 1778 until 1779 and to the Netherlands from 1780 until 1782, and the younger Adams accompanied his father on these journeys.

Adams acquired an education at institutions such as Leiden University. For nearly three years, at the age of 14, he accompanied Francis Dana as a secretary on a mission to St. Petersburg, Russia, to obtain recognition of the new United States. He spent time in Finland, Sweden, and Denmark and, in 1804, published a travel report of Silesia.[7]

During these years overseas, Adams gained a mastery of French and Dutch and a familiarity with German and other European languages. He entered Harvard College and graduated in 1788, Phi Beta Kappa.[8] (Adams House at Harvard College is named in honor of Adams and his father.)

He apprenticed as a lawyer with Theophilus Parsons in Newburyport, Massachusetts, from 1787 to 1789. He was admitted to the bar in 1791 and began practicing law in Boston.

Early career

George Washington appointed Adams minister to the Netherlands (at the age of 26) in 1794 and Portugal in 1796. He then was promoted to the Berlin Legation.

When the elder Adams became president, he appointed his son in 1797 as Minister to Prussia at Washington's urging. There Adams signed the renewal of the very liberal Prussian-American Treaty of Amity and Commerce after negotiations with Prussian Foreign Minister Count Karl-Wilhelm Finck von Finckenstein. He served at that post until 1801.

While serving abroad, Adams married Louisa Catherine Johnson, the daughter of an American merchant, in a ceremony at the church of All Hallows-by-the-Tower, London. Adams remains the only president to have a foreign-born First Lady.

On his return to the United States Adams was appointed a commissioner of bankruptcy in Boston by a Federal District Judge. However, Thomas Jefferson rescinded this appointment. He again tried his hand as a lawyer, but shortly entered politics. John Quincy Adams was elected a member of the Massachusetts State Senate in April 1802. In November 1802 he lost in a congressional election where he was the Federalist candidate for a seat in the United States House of Representatives.[9]

The Massachusetts General Court elected Adams as a Federalist to the U.S. Senate soon after, and he served from March 4, 1803, until 1808, when he broke with the Federalist Party. Adams, as a Senator, had supported the Louisiana Purchase and Jefferson's Embargo Act, actions which made him very unpopular with Massachusetts Federalists. The Federalist-controlled Massachusetts Legislature chose a replacement for Adams on June 3, 1808, several months early. On June 8, Adams broke with the Federalists, resigned his Senate seat, and became a Democrat-Republican.[10] While a member of the Senate, Adams also served as a professor of rhetoric at Harvard University.[11]

New President James Madison appointed Adams as the first ever United States Minister to Russia in 1809. Louisa Adams was with him in St. Petersburg almost the entire time. While not officially a diplomat, Louisa Adams did serve an invaluable role as wife-of-diplomat, becoming a favorite of the tsar and making up for her husband's utter lack of charm. She was an indispensable part of the American mission.[12] In 1812 Adams reported back to Washington the news of Napoleon's invasion of Russia in 1812 and his disastrous retreat. In 1814, Adams was recalled from Russia to serve as chief negotiator of the U.S. commission for the Treaty of Ghent, which ended the War of 1812 between the United States and Great Britain. Finally, he was sent to be minister to the Court of St. James's (Britain) from 1815 until 1817.[10]

Secretary of State

Adams served as Secretary of State in the Cabinet of President James Monroe from 1817 until 1825, a tenure during which he was instrumental in the acquisition of Florida. Typically, his views concurred with those espoused by Monroe. As Secretary of State, he negotiated the Adams-Onís Treaty and wrote the Monroe Doctrine, which warned European nations against meddling in the affairs of the Western Hemisphere. Adams' interpretation of neutrality was so strict that he refused to cooperate with Great Britain in suppressing the slave trade.[citation needed] On Independence Day 1821, in response to those who advocated American support for Spanish America's independence movement from Spain,[13] Adams gave a speech in which he said that American policy was moral support for but not armed intervention on behalf of independence movements, stating that America "goes not abroad in search of monsters to destroy."[14] After the Napoleonic wars Spain lost control of most of the American colonies. They revolted and declared independence. Rebels used American ports to equip privateers to attack Spanish ships, a practice defended by Henry Clay, who severely criticized both Monroe and Adams for their more cautious wait-and-see policy. The Floridas, still Spanish territory but with no Spanish presence to speak of, became a refuge for runaway slaves and Indian raiders. Spain was not in charge. Monroe sent in General Andrew Jackson who pushed the Seminole Indians south, executed two British merchants who were supplying weapons, deposed one governor and named another, and left an American garrison in occupation. Jackson thought he had Washington's approval, but the orders were vague. President Monroe and all his cabinet, except Adams, believed Jackson had exceeded his instructions. Secretary of War John C. Calhoun proposed to punish Jackson. Adams argued that since Spain had proved incapable of policing her territories, the United States was obliged to act in self-defense. Adams so ably justified Jackson's conduct as to silence protests either from Spain or Britain. Congress debated the question, with Clay as the leading opponent of Jackson, but it would not disapprove of what Jackson had done.

Adams negotiated the "Transcontinental Treaty" with Spain in 1819 that turned Florida over to the U.S. and resolved border issues regarding the Louisiana Purchase. The treaty recognized Spanish control of Texas (a claim taken up by Mexico when it declared independence of Spain). The post of Secretary of State was the normal path to the White House. After 1820 Adams, intent on winning the presidency, was less successful at the State Department. He failed to make key commercial treaties because he feared the necessary American concessions would be used to attack his candidacy. Instead the nation suffered from trade wars that could have been prevented.

1824–25 presidential election

As the election of 1824 drew near people began looking for candidates. New England voters admired Adams' patriotism and political skills and it was mainly due to their support that he entered the race. The old caucus system of the Democratic-Republican Party had collapsed; indeed the entire First Party System had collapsed and the election was a free-for-all based on regional support. Adams had a strong base in New England. His opponents included John C. Calhoun, William Crawford, Henry Clay and the hero of New Orleans, Andrew Jackson. During the campaign Calhoun dropped out, and Crawford fell ill giving further support to the other candidates. When the election day came, Andrew Jackson won, although narrowly, pluralities of the popular and electoral votes, but not the necessary majority of electoral votes.

Under the terms of the Twelfth Amendment, the presidential election was thrown to the House of Representatives to vote on the top three candidates: Jackson, Adams, and Crawford. Clay had come in fourth place and thus was ineligible, but he retained considerable power and influence as Speaker of the House. Crawford was unviable due to the stroke.

Clay's personal dislike for Jackson and the similarity of his American System to Adams' position on tariffs and internal improvements caused him to throw his support to Adams, who was elected by the House on February 9, 1825, on the first ballot. Adams' victory shocked Jackson, who had gained the plurality of the electoral and popular votes and fully expected to be elected president. When Adams appointed Clay as Secretary of State—the position that Adams and his three predecessors had held before becoming President—Jacksonian Democrats were outraged, and claimed that Adams and Clay had struck a "corrupt bargain." This contention overshadowed Adams' term and greatly contributed to Adams' loss to Jackson four years later, in the 1828 election.

Presidency 1825–1829

Adams served as the sixth President of the United States from March 4, 1825, to March 4, 1829. He took the oath of office on a book of laws, instead of the more traditional Bible, to preserve the separation of church and state.[15][16]

Politics

Adams' singular intelligence, vast experience, unquestionable integrity, and devotion to his country should have made him a great chief executive. But like his father he lacked political sense and an ability to command public support, and his contentious spirit spelled defeat for him personally and for many of his policies. He proposed a comprehensive program of internal improvements (roads, ports and canals), the creation of a national university, and federal support for the arts and sciences. He favored a high tariff to encourage the building of factories, and restricted land sales to slow the movement west. Opposition from the states' rights faction quickly killed the proposals,[17] Even more serious was the attack by the followers of Jackson, who accused him of being a partner to a "corrupt bargain" to obtain Clay's support in the election and then appoint him secretary of state. Refusing to play politics, Adams did little or nothing to build up a personal following committed to his re-election. He refused to discharge federal officeholders when they actively joined the opposition, and even considered appointing Jackson to his cabinet. Losing control of Congress in the elections of 1826, he still persisted in his independent policies and thus insured his own overwhelming defeat by Jackson two years later. He was particularly embittered by the unfounded accusations of fraud and extravagance made against him during the campaign by his opponents (not to mention the false accusation that he had pimped for the Czar of Russia[18]). The Adams administration recorded no major legislative, diplomatic, military or administrative achievements. Congress did pass the high Tariff of 1828--the "tariff of abominations" that created a violent outcry especially in South Carolina. Jackson defeated Adams in a landslide in 1828, and created the the modern Democratic party and thus inaugurating the Second Party System.

Domestic policies

During his term, he worked on developing the American System, consisting of a high tariff to support internal improvements such as road-building, and a national bank to encourage productive enterprise and form a national currency. In his first annual message to Congress, Adams presented an ambitious program for modernization that included roads, canals, a national university, an astronomical observatory, and other initiatives. The support for his proposals was limited, even from his own party. His critics accused him of unseemly arrogance because of his narrow victory. Most of his initiatives were opposed in Congress by Jackson's supporters, who remained outraged over the 1824 election.

Nonetheless, some of his proposals were adopted, specifically the extension of the Cumberland Road into Ohio with surveys for its continuation west to St. Louis; the beginning of the Chesapeake and Ohio Canal, the construction of the Delaware and Chesapeake Canal and the Portland to Louisville Canal around the falls of the Ohio; the connection of the Great Lakes to the Ohio River system in Ohio and Indiana; and the enlargement and rebuilding of the Dismal Swamp Canal in North Carolina.

One of the issues which divided the administration was protective tariffs. Henry Clay was a leading advocate, but Vice President John C. Calhoun was an opponent. After Adams lost control of Congress in 1827, the situation became more complicated. By signing into law the Tariff of 1828 (also known as the Tariff of Abominations), extremely unpopular in the South, he limited his chances to achieve more during his presidency.

Adams and Clay set up a new party, the National Republican Party, but it never took root in the states. In the elections of 1826, Adams and his supporters lost control of Congress. New York Senator Martin Van Buren, a future president and follower of Jackson, became one of the leaders of the senate.

Much of Adams' political difficulties were due to his refusal, on principle, to replace members of his administration who supported Jackson (contending that no one should be removed from office except for incompetence). For example, his Postmaster General, John McLean, continued in office through the Adams administration, although he was using his powers of patronage to curry favor with Jacksonites.

Another blow to Adams' presidency was his generous policy toward Native Americans. Settlers on the frontier, who were constantly seeking to move westward, cried for a more expansionist policy. When the federal government tried to assert authority on behalf of the Cherokees, the governor of Georgia took up arms. In contrast, Andrew Jackson and Martin Van Buren instigated the policy of Indian removal to the west (i.e. the Trail of Tears).[19] Adams defended his domestic agenda as continuing Monroe's policies.

Honors presidents' deaths

On July 4, 1826, former presidents Thomas Jefferson and John Adams died. John Quincy Adams gave an Executive Order on July 11, 1826, that was a commemoration to both Thomas Jefferson and John Adams. The order included a day of rest at each military station and flags were set at half mast.[20]

Foreign policies

Adams is regarded as one of the greatest diplomats in American history, and during his tenure as Secretary of State he was the chief designer of the Monroe Doctrine.[21]

On July 4, 1821, he gave an address to Congress:

... But she goes not abroad, in search of monsters to destroy. She is the well-wisher to the freedom and independence of all. She is the champion and vindicator only of her own.[22]

During his term as president, however, Adams achieved little of consequence in foreign affairs. A reason for this was the opposition he faced in Congress, where his rivals prevented him from succeeding.[21]

Among the few diplomatic achievements of his administration were treaties of reciprocity with a number of nations, including Denmark, Mexico, the Hanseatic League, the Scandinavian countries, Prussia and Austria. However, thanks to the successes of Adams' diplomacy during his previous eight years as Secretary of State, most of the foreign policy issues he would have faced had been resolved by the time he became President.

Administration and Cabinet

| The Adams cabinet | ||

|---|---|---|

| Office | Name | Term |

| President | John Quincy Adams | 1825–1829 |

| Vice President | John C. Calhoun | 1825–1829 |

| Secretary of State | Henry Clay | 1825–1829 |

| Secretary of the Treasury | Richard Rush | 1825–1829 |

| Secretary of War | James Barbour | 1825–1828 |

| Peter B. Porter | 1828–1829 | |

| Attorney General | William Wirt | 1825–1829 |

| Secretary of the Navy | Samuel L. Southard | 1825–1829 |

Judicial appointments

Supreme Court

- Robert Trimble – June 16, 1826 – August 25, 1828

Other courts

Adams was able to make eleven other appointments, all to United States district courts.

States admitted to the Union

None

Departure from office

John Quincy Adams left office on March 4, 1829, after losing the election of 1828 to Andrew Jackson. Adams did not attend the inauguration of his successor, Andrew Jackson, who had openly snubbed him by refusing to pay the traditional "courtesy call" to the outgoing President during the weeks before his own inauguration. He was one of only three Presidents who chose not to attend their respective successor's inauguration; the others were his father and Andrew Johnson.

Election of 1828

After the inauguration of Adams in 1825,[23][24] Jackson resigned from his senate seat. For four years he worked hard, with help from his supporters in Congress, to defeat Adams in the Presidential election of 1828. The campaign was very much a personal one. As was the tradition of the day and age in American presidential politics, neither candidate personally campaigned, but their political followers organized many campaign events. Both candidates were rhetorically attacked in the press. This reached a low point when the press accused Jackson's wife Rachel of bigamy. She died a few weeks after the elections. Jackson said he would forgive those who insulted him, but he would never forgive the ones who attacked his wife.

Adams lost the election by a decisive margin, 178–83 in the Electoral College. He won exactly the same states that his father had won in the election of 1800: the New England states, New Jersey, and Delaware. Jackson won everything else except for New York, which gave 16 of its electoral votes to Adams, and Maryland, which cast 6 of its votes for Adams.

Member of Congress

Adams did not retire after leaving office. Instead he ran for and was elected to the House of Representatives in the 1830 elections as a National Republican. He was the first president to serve in Congress after his term of office, and one of only two former presidents to do so; Andrew Johnson later served in the Senate. He was elected to eight terms, serving as a Representative for 17 years, from 1831 until his death. Through redistricting Adams represented three districts in succession: Massachusetts's 11th congressional district (1831–1833), 12th congressional district (1833–1837), and 8th congressional district (1837–1843), serving from the 22nd to the 30th Congresses. He became a Whig in 1834.

In Congress, he was chair of the Committee on Commerce and Manufactures (23rd, 24th, 25th, 26th, 28th and 29th), the Committee on Indian Affairs (for the 27th Congress) and the Committee on Foreign Affairs (also for the 27th Congress). He became an important antislavery voice in the Congress. During the years 1836–37 Adams presented many petitions for the abolition of slavery and the slave trade in the District of Columbia and elsewhere to Congress. The Gag rule prevented discussion of slavery from 1836 to 1844, but he frequently managed to evade it by parliamentary skill.

In 1834 he unsuccessfully ran as the Anti-Masonic candidate[25] for Governor of Massachusetts, losing to John Davis. Adams then continued his legal career.

In 1841, he had the case of a lifetime, representing the defendants in United States v. The Amistad Africans in the Supreme Court of the United States. He successfully argued that the Africans, who had seized control of a Spanish ship on which they were being transported illegally as slaves, should not be extradited or deported to Cuba (still under Spanish control) but should be considered free. Under Andrew Jackson's successor Martin Van Buren, the United States Department of Justice argued the Africans should be deported for having mutinied and killed officers on the ship. Adams won their freedom, with the chance to stay in the United States or return to Africa. Adams made the argument because the U.S. had prohibited the international slave trade, although it allowed internal slavery. He never billed for his services in the Amistad case.[26]

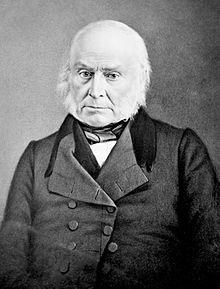

Adams sat for the earliest confirmed photograph still in existence of a U.S. president in 1843.[27] The original daguerreotype is in the collection of the National Portrait Gallery of the Smithsonian Institution.[28]

Although there is no indication that the two were close, Adams met Abraham Lincoln during the latter's sole term as a member of the House of Representatives, from 1847 until Adams' death. Thus, it has been suggested that Adams is the only major figure in American history who knew both the Founding Fathers and Abraham Lincoln.[citation needed]

Death and burial

On February 21, 1848, the House of Representatives was discussing the matter of honoring US Army officers who served in the Mexican-American War. Adams firmly opposed this idea, so when the rest of the house erupted into 'ayes', he cried out, 'No!'[29] Immediately thereafter, Adams collapsed, having suffered a massive cerebral hemorrhage.[30] Two days later, on February 23, he died with his wife and son at his side in the Speaker's Room inside the Capitol Building in Washington, D.C. His last words were reported to have been, "This is the last of Earth. I am content."

His original interment was temporary, in the public vault at the Congressional Cemetery in Washington, D.C.. Later, he was interred in the family burial ground in Quincy at the First Unitarian Church, called Hancock Cemetery. After his wife's death, his son, Charles Francis Adams, had him reinterred with his wife in a family crypt in the United First Parish Church across the street. His parents are also buried there, and both tombs are viewable. Adams' original tomb at Hancock Cemetery is still there, marked simply "J.Q. Adams".[31]

Family

John Quincy Adams and Louisa Catherine (Johnson) Adams had three sons and a daughter. Louisa was born in 1811 but died in 1812 while the family was in Russia. They named their first son George Washington Adams (1801–1829) after the first president. Both George and their second son, John (1803–1834), led troubled lives and died in early adulthood.[32][33] (George committed suicide and John was expelled from Harvard before his 1823 graduation.)

Adams' youngest son, Charles Francis Adams (who named his own son John Quincy), also pursued a career in diplomacy and politics. In 1870 Charles Francis built the first memorial presidential library in the United States, to honor his father. The Stone Library includes over 14,000 books written in twelve languages. The library is located in the "Old House" at Adams National Historical Park in Quincy, Massachusetts.

John Adams and John Quincy Adams were the first father and son to each serve as president (the others being George H. W. Bush and George W. Bush). In addition, each Adams served only one term as President.

Harvard professor of rhetoric

Disowned by the Federalists and not fully accepted by the Republicans, Adams used his Boylston Professorship of Rhetoric and Oratory at Harvard as a new base.[34] Adams' devotion to classical rhetoric shaped his response to public issues. He remained inspired by classical rhetorical ideals long after the neo-classicalism and deferential politics of the founding generation had been eclipsed by the commercial ethos and mass democracy of the Jacksonian Era. Many of Adams's idiosyncratic positions were rooted in his abiding devotion to the Ciceronian ideal of the citizen-orator "speaking well" to promote the welfare of the polis.[35] Adams was influenced by the classical republican ideal of civic eloquence espoused by British philosopher David Hume.[36] Adams adapted these classical republican ideals of public oratory to America, viewing the multilevel political structure as ripe for "the renaissance of Demosthenic eloquence." Adams's Lectures on Rhetoric and Oratory (1810) looks at the fate of ancient oratory, the necessity of liberty for it to flourish, and its importance as a unifying element for a new nation of diverse cultures and beliefs. Just as civic eloquence failed to gain popularity in Britain, in the United States interest faded in the second decade of the 18th century as the "public spheres of heated oratory" disappeared in favor of the private sphere.[37]

See also

- Adams political family

- Adams-Onís Treaty

- Mount Quincy Adams

- Treaty of Ghent

- Mendi Bible

- U.S. presidential election, 1820

- U.S. presidential election, 1824

- U.S. presidential election, 1828

- List of United States political appointments that crossed party lines

Pronunciation note

- ^ The name Quincy has subsequently been used for at least nineteen other places in the United States. Those places were either directly or indirectly named for John Quincy Adams (for example, Quincy, Illinois was named in honor of Adams while Quincy, California was named for Quincy, Illinois). The Quincy family name was Template:Pron-en, as is the name of the city in Massachusetts where Adams was born ( of Adams' name). However, all of the other place names are locally Template:Pron-en. Though technically incorrect, this pronunciation is also commonly used for Adams' middle name. Sources: "Frequently Asked Questions". City of Quincy. Retrieved 2009-07-09.; Wead, Doug (2005). The raising of a president: the mothers and fathers of our nation's leaders. New York: Atria Books. p. 59. ISBN 0743497260. OCLC 57358429. Retrieved 2009-07-09.

Notes

- ^ "John Quincy Adams". Metropolitan Museum of Art. Retrieved 2009-09-04.

- ^ The name "Quincy" having come from Abigail's maternal grandfather, Colonel John Quincy, after whom Quincy, Massachusetts is also named.Herring, James (1853). The National Portrait Gallery of Distinguished Americans. D. Rice & A.N. Hart. p. 1. Retrieved 2008-10-22.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ Bemis (1949)

- ^ See Howe (2007)

- ^ This Day in History in 1828, www.history.com, retrieved 3-13-2008

- ^ The text of his 50-volume diary (plus a supplemental volume) at the Massachusetts Historical Society can be found at Massshist.org

- ^ John Quincy Adams: Letters on Silesia: Written During a Tour Through that Country in the Years 1800,1801 Books.Google.com

- ^ U.S. Presidents Who Are Phi Beta Kappa Members, Phi Beta Kappa website, accessed Oct 4, 2009

- ^ McCullough. John Adams. pp. 575–576

- ^ a b NPS bio of JQA

- ^ David McCoulough. John Adams. (New York: Simon & Schuster, 2005) p. 587

- ^ Allgor, (1997).

- ^ Francis Sempa essay

- ^ Adams speech July 4, 1821

- ^ "Presidential Inaugurations Past and Present: A Look at the History Behind the Pomp and Circumstance". Fpc.state.gov. Retrieved 2008-09-16.

- ^ Romero, Frances (15 January 2009). "A Brief History Of: Swearing In". Time (magazine). Retrieved 18 January 2009.

- ^ Lynn H. Parsons, John Quincy Adams (1999)

- ^ The charge was made by Isaac Hill, leader of the Jacksonians in New Hampshire. Lynn Parsons, Andrew Jackson, John Quincy Adams, and the Election of 1828 (2009) P. 150

- ^ Ronald N. Satz, American Indian Policy in the Jacksonian Era (1975)

- ^ The American Presidency Project (1999–2010). "Executive Order July 11, 1826".

- ^ a b Bemis John Quincy Adams and the Union (1956)

- ^ Miller Center for Public Affairs, University of Virginia

- ^ Adams, John Quincy Memoirs of John Quincy Adams: comprising portions of his diary, Volume 6, accessed Oct 8, 2009

- ^ "Wednesday, February 9, 1825". Library of Congress. Retrieved 2008-09-16.

- ^ Richards, Leonard L. (1986). The Life and Times of Congressman John Quincy Adams. Oxford [Oxfordshire]: Oxford University Press. p. 48. ISBN 0-19-504026-0.

- ^ Miller, William Lee, pg 402

- ^ Krainik, Clifford. "Face the Lens, Mr. President: A Gallery of Photographic Portraits of 19th-Century U.S. Presidents" (PDF). The White House Historical Association. Retrieved 2009-09-04.

- ^ "CAP Search results related to Bishop". National Portrait Gallery. Retrieved 2009-09-04.

- ^ Parker, Theodore (1848). A discourse occasioned by the death of John Quincy Adams. Boston: Published by Bela Marsh, 25 Cornhill. p. 26. OCLC 6354870. Retrieved 2009-08-02.

- ^ Widmer, Edward L. (2008). Ark of the liberties: America and the world. New York: Hill and Wang. p. 120. ISBN 978-0809027354. OCLC 191882004. Retrieved 2009-08-02.

- ^ John Quincy Adams (1767–1848) – Find A Grave Memorial (original burial site

- ^ "Brief Biographies of Jackson Era Characters (A)". Jmisc.net. Retrieved 2008-09-16.

- ^ Shepherd, Jack, Cannibals of the Heart: A Personal Biography of Louisa Catherine and John Quincy Adams, New York, McGraw-Hill 1980

- ^ He was appointed in 1805, after turning down the presidency of Harvard.

- ^ Lyon Rathbun, "The Ciceronian Rhetoric of John Quincy Adams." Rhetorica (2000) 18(2): 175–215.

- ^ See David Hume, "Of Eloquence," in Essays, Political and Moral *1742)

- ^ Adam S. Potkay, "Theorizing Civic Eloquence in the Early Republic: the Road from David Hume to John Quincy Adams." Early American Literature (1999) 34(2): 147–170.

References

- Allgor, Catherine (1997). "'A Republican in a Monarchy': Louisa Catherine Adams in Russia". Diplomatic History. 21 (1): 15–43. doi:10.1111/1467-7709.00049. ISSN 0145-2096.

{{cite journal}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help) Fulltext in Swetswise, Ingenta and Ebsco. - Bemis, Samuel Flagg. John Quincy Adams and the Foundations of American Foreign Policy. vol 1 (1949), John Quincy Adams and the Union (1956), vol 2. Pulitzer prize biography.

- Crofts, Daniel W. (1997). "Congressmen, Heroic and Otherwise". Reviews in American History. 25 (2): 243–247. ISSN 0048-7511.

{{cite journal}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help) Fulltext in Project Muse. Adams role in antislavery petitions debate 1835–44. - Holt, Michael F. The Rise and Fall of the American Whig Party: Jacksonian Politics and the Onset of the Civil War. 1999.

- Lewis, James E., Jr. John Quincy Adams: Policymaker for the Union. Scholarly Resources, 2001. 164 pp.

- Mattie, Sean (2003). "John Quincy Adams and American Conservatism". Modern Age. 45 (4): 305–314. ISSN 0026-7457.

{{cite journal}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help) fulltext online - McMillan, Richard (2001). "Election of 1824: Corrupt Bargain or the Birth of Modern Politics?". New England Journal of History. 58 (2): 24–37.

{{cite journal}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help) - Miller, Chandra (2000). "'Title Page to a Great Tragic Volume': the Impact of the Missouri Crisis on Slavery, Race, and Republicanism in the Thought of John C. Calhoun and John Quincy Adams". Missouri Historical Review. 94 (4): 365–388. ISSN 0026-6582.

{{cite journal}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help) Shows that both men considered splitting the country as a solution. - Miller, William Lee (1995). Arguing About Slavery. John Quincy Adams and the Great Battle in the United States Congress. Vintage Books. ISBN 0-3945-6922-9.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|city=ignored (|location=suggested) (help) - Nagel, Paul C. John Quincy Adams: A Public Life, a Private Life (1999)

- Parsons, Lynn Hudson (1 October 2003). "In Which the Political Becomes Personal, and Vice Versa: the Last Ten Years of John Quincy Adams and Andrew Jackson". Journal of the Early Republic. 23 (3): 421–443. doi:10.2307/3595046. ISSN 0275-1275.

{{cite journal}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help) - Parsons, Lynn H. The Birth of Modern Politics: Andrew Jackson, John Quincy Adams, and the Election of 1828 (2009) excerpt and text search

- Portolano, Marlana (2000). "John Quincy Adams's Rhetorical Crusade for Astronomy". Isis. 91 (3): 480–503. doi:10.1086/384852. ISSN 0021-1753.

{{cite journal}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help) Fulltext online at Jstor and Ebsco. He tried and failed to create a national observatory. - Potkay, Adam S. (1999). "Theorizing Civic Eloquence in the Early Republic: the Road from David Hume to John Quincy Adams". Early American Literature. 34 (2): 147–170. ISSN 0012-8163.

{{cite journal}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help) Fulltext online at Swetswise and Ebsco. - Rathbun, Lyon (2000). "The Ciceronian Rhetoric of John Quincy Adams". Rhetorica. 18 (2): 175–215. doi:10.1525/rh.2000.18.2.175. ISSN 0734-8584.

{{cite journal}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help) - Remini, Robert V. (2002). John Quincy Adams. New York: Times Books. ISBN 0805069399.

{{cite book}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help) - Wood, Gary V. (2004). Heir to the Fathers: John Quincy Adams and the Spirit of Constitutional Government. Ladham, MD: Lexington. ISBN 0739106015.

{{cite book}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help) - Brinkley, Alan (2004). The American Presidency. Boston: Houghton Mifflin. ISBN 0618382739.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help)

Primary sources

- Adams, John Quincy. Memoirs (12 vol 1874–77), partly online, books.google.com

- Adams, John Quincy. Writings ed. W. C. Ford (7 vol. 1913–1917), vol 7 online, books.google.com

- Butterfield, L. H. et al., eds., The Adams Papers (1961– ). Multivolume letterpress edition of all letters to and from major members of the Adams family, plus their diaries; still incomplete.Masshist.org

- Adams, John Quincy. Lectures on Rhetoric and Oratory, 1810 (facsimile ed., 1997, Scholars' Facsimiles & Reprints, ISSN 9780820115078).

External links

- Official NPS website: Adams National Historical Park

- White House Biography, whitehouse.gov

- John Quincy Adams Biography and Fact File, american-presidents.com

- Biography of John Quincy Adams, usa-presidents.info

- Biography of John Quincy Adams by Appleton's and Stanley L. Klos, johnqadams.org

- Inaugural Address, yale.edu

- State of the Union Addresses: 1825, 1826, 1827, 1828, usa-presidents.info

- July 4, 1821, Independence Day Speech, fff.org

- Works by John Quincy Adams at Project Gutenberg

- United States Congress. "John Quincy Adams (id: A000041)". Biographical Directory of the United States Congress.

- Medical and Health history of John Quincy Adams, doctorzebra.com

- Armigerous American Presidents Series, americanheraldry.org

- The Jubilee of the Constitution: A Discourse, lonang.com

- Dermot MacMorrogh,: or, The conquest of Ireland. An historical tale of the twelfth century. In four cantos./ By John Quincy Adams, quod.lib.umich.edu

- Essay on John Quincy Adams and essays on each member of his cabinet and First Lady from the Miller Center of Public Affairs, millercenter.org

- Poems of religion and society.: With notices of his life and character by John Davis and T. H. Benton, quod.lib.umich.edu

- Encyclopedia Britannica: Adams, John Quincy, encyclopedia.jrank.org

- Collection of John Quincy Adams Letters, familytales.org

- Nagel, Paul. Descent from Glory: Four Generations of the John Adams Family., Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1999 hup.harvard.edu

- Adams, John Quincy. Life in a New England Town, 1787, 1788: Diary of John Quincy Adams. Published in 1903. Diary of J.Q. Adams while he apprenticed as a lawyer in Newburyport, Massachusetts under Theophilus Parsons. books.google.com

- Index entry for John Quincy Adams at Poets' Corner, theotherpages.org

- Presidents of the United States

- United States presidential candidates, 1820

- United States presidential candidates, 1824

- United States presidential candidates, 1828

- United States Secretaries of State

- Massachusetts State Senators

- United States Senators from Massachusetts

- United States ambassadors to the Netherlands

- United States ambassadors to Russia

- United States ambassadors to the United Kingdom

- United States ambassadors to Prussia

- Members of the United States House of Representatives from Massachusetts

- Massachusetts lawyers

- Harvard University alumni

- Leiden University alumni

- Harvard University faculty

- Adams family

- John Quincy Adams

- Presidency of John Quincy Adams

- Children of Presidents of the United States

- People from Quincy, Massachusetts

- People from Boston, Massachusetts

- 19th-century people

- People from Norfolk County, Massachusetts

- American Unitarians

- English Americans

- Deaths from cerebral hemorrhage

- People from Braintree, Massachusetts

- Massachusetts Whigs

- Quincy family

- 1767 births

- 1848 deaths

- 19th-century presidents of the United States