Climate change

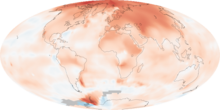

Global warming is the increase in the average temperature of Earth's near-surface air and oceans since the mid-20th century and its projected continuation. According to the 2007 Fourth Assessment Report by the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC), global surface temperature increased 0.74 ± 0.18 °C (1.33 ± 0.32 °F) during the 20th century.[2][A] Most of the observed temperature increase since the middle of the 20th century has been caused by increasing concentrations of greenhouse gases, which result from human activity such as the burning of fossil fuel and deforestation.[3] Global dimming, a result of increasing concentrations of atmospheric aerosols that block sunlight from reaching the surface, has partially countered the effects of warming induced by greenhouse gases.

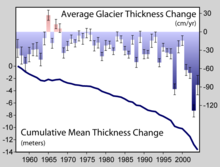

Climate model projections summarized in the latest IPCC report indicate that the global surface temperature is likely to rise a further 1.1 to 6.4 °C (2.0 to 11.5 °F) during the 21st century.[2] The uncertainty in this estimate arises from the use of models with differing sensitivity to greenhouse gas concentrations and the use of differing estimates of future greenhouse gas emissions. An increase in global temperature will cause sea levels to rise and will change the amount and pattern of precipitation, probably including expansion of subtropical deserts.[4] Warming is expected to be strongest in the Arctic and would be associated with continuing retreat of glaciers, permafrost and sea ice. Other likely effects include changes in the frequency and intensity of extreme weather events, species extinctions, and changes in agricultural yields. Warming and related changes will vary from region to region around the globe, though the nature of these regional variations is uncertain.[5] As a result of contemporary increases in atmospheric carbon dioxide, the oceans have become more acidic; a result that is predicted to continue.[6][7]

The scientific consensus is that anthropogenic global warming is occurring.[8][9][10][B] Nevertheless, political and public debate continues. The Kyoto Protocol is aimed at stabilizing greenhouse gas concentration to prevent a "dangerous anthropogenic interference".[11] As of November 2009, 187 states had signed and ratified the protocol.[12]

Temperature changes

Evidence for warming of the climate system includes observed increases in global average air and ocean temperatures, widespread melting of snow and ice, and rising global average sea level.[13][14][15][16][17] The most common measure of global warming is the trend in globally averaged temperature near the Earth's surface. Expressed as a linear trend, this temperature rose by 0.74 ± 0.18 °C over the period 1906–2005. The rate of warming over the last half of that period was almost double that for the period as a whole (0.13 ± 0.03 °C per decade, versus 0.07 °C ± 0.02 °C per decade). The urban heat island effect is estimated to account for about 0.002 °C of warming per decade since 1900.[18] Temperatures in the lower troposphere have increased between 0.13 and 0.22 °C (0.22 and 0.4 °F) per decade since 1979, according to satellite temperature measurements. Temperature is believed to have been relatively stable over the one or two thousand years before 1850, with regionally varying fluctuations such as the Medieval Warm Period and the Little Ice Age.[19]

Estimates by NASA's Goddard Institute for Space Studies (GISS) and the National Climatic Data Center show that 2005 was the warmest year since reliable, widespread instrumental measurements became available in the late 1800s, exceeding the previous record set in 1998 by a few hundredths of a degree.[20][21] Estimates prepared by the World Meteorological Organization and the Climatic Research Unit show 2005 as the second warmest year, behind 1998.[22][23] Temperatures in 1998 were unusually warm because the strongest El Niño in the past century occurred during that year.[24] Global temperature is subject to short-term fluctuations that overlay long term trends and can temporarily mask them. The relative stability in temperature from 2002 to 2009 is consistent with such an episode.[25][26]

Temperature changes vary over the globe. Since 1979, land temperatures have increased about twice as fast as ocean temperatures (0.25 °C per decade against 0.13 °C per decade).[27] Ocean temperatures increase more slowly than land temperatures because of the larger effective heat capacity of the oceans and because the ocean loses more heat by evaporation.[28] The Northern Hemisphere warms faster than the Southern Hemisphere because it has more land and because it has extensive areas of seasonal snow and sea-ice cover subject to ice-albedo feedback. Although more greenhouse gases are emitted in the Northern than Southern Hemisphere this does not contribute to the difference in warming because the major greenhouse gases persist long enough to mix between hemispheres.[29]

The thermal inertia of the oceans and slow responses of other indirect effects mean that climate can take centuries or longer to adjust to changes in forcing. Climate commitment studies indicate that even if greenhouse gases were stabilized at 2000 levels, a further warming of about 0.5 °C (0.9 °F) would still occur.[30]

External forcings

External forcing refers to processes external to the climate system (though not necessarily external to Earth) that influence climate. Climate responds to several types of external forcing, such as radiative forcing due to changes in atmospheric composition (mainly greenhouse gas concentrations), changes in solar luminosity, volcanic eruptions, and variations in Earth's orbit around the Sun.[31] Attribution of recent climate change focuses on the first three types of forcing. Orbital cycles vary slowly over tens of thousands of years and thus are too gradual to have caused the temperature changes observed in the past century.

Greenhouse gases

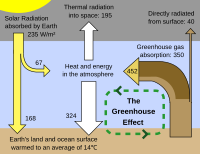

The greenhouse effect is the process by which absorption and emission of infrared radiation by gases in the atmosphere warm a planet's lower atmosphere and surface. It was proposed by Joseph Fourier in 1824 and was first investigated quantitatively by Svante Arrhenius in 1896.[32] The question in terms of global warming is how the strength of the presumed greenhouse effect changes when human activity increases the concentrations of greenhouse gases in the atmosphere.

Naturally occurring greenhouse gases have a mean warming effect of about 33 °C (59 °F).[33][C] The major greenhouse gases are water vapor, which causes about 36–70 percent of the greenhouse effect; carbon dioxide (CO2), which causes 9–26 percent; methane (CH4), which causes 4–9 percent; and ozone (O3), which causes 3–7 percent.[34][35][36] Clouds also affect the radiation balance, but they are composed of liquid water or ice and so have different effects on radiation from water vapor.

Human activity since the Industrial Revolution has increased the amount of greenhouse gases in the atmosphere, leading to increased radiative forcing from CO2, methane, tropospheric ozone, CFCs and nitrous oxide. The concentrations of CO2 and methane have increased by 36% and 148% respectively since 1750.[37] These levels are much higher than at any time during the last 650,000 years, the period for which reliable data has been extracted from ice cores.[38][39][40] Less direct geological evidence indicates that CO2 values higher than this were last seen about 20 million years ago.[41] Fossil fuel burning has produced about three-quarters of the increase in CO2 from human activity over the past 20 years. Most of the rest is due to land-use change, particularly deforestation.[42]

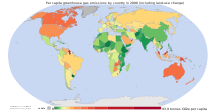

Over the last three decades of the 20th century, GDP per capita and population growth were the main drivers of increases in greenhouse gas emissions.[43] CO2 emissions are continuing to rise due to the burning of fossil fuels and land-use change.[44][45]: 71 Emissions scenarios, estimates of changes in future emission levels of greenhouse gases, have been projected that depend upon uncertain economic, sociological, technological, and natural developments.[46] In most scenarios, emissions continue to rise over the century, while in a few, emissions are reduced.[47][48] These emission scenarios, combined with carbon cycle modelling, have been used to produce estimates of how atmospheric concentrations of greenhouse gases will change in the future. Using the six IPCC SRES "marker" scenarios, models suggest that by the year 2100, the atmospheric concentration of CO2 could range between 541 and 970 ppm.[49] This is an increase of 90-250% above the concentration in the year 1750. Fossil fuel reserves are sufficient to reach these levels and continue emissions past 2100 if coal, tar sands or methane clathrates are extensively exploited.[50]

The destruction of stratospheric ozone by chlorofluorocarbons is sometimes mentioned in relation to global warming. Although there are a few areas of linkage, the relationship between the two is not strong. Reduction of stratospheric ozone has a cooling influence on the entire troposphere, but a warming influence on the surface.[51] Substantial ozone depletion did not occur until the late 1970s.[52] Ozone in the troposphere (the lowest part of the Earth's atmosphere) does contribute to surface warming.[53]

Aerosols and soot

Global dimming, a gradual reduction in the amount of global direct irradiance at the Earth's surface, has partially counteracted global warming from 1960 to the present.[54] The main cause of this dimming is aerosols produced by volcanoes and pollutants. These aerosols exert a cooling effect by increasing the reflection of incoming sunlight. The effects of the products of fossil fuel combustion—CO2 and aerosols—have largely offset one another in recent decades, so that net warming has been due to the increase in non-CO2 greenhouse gases such as methane.[55] Radiative forcing due to aerosols is temporally limited due to wet deposition which causes aerosols to have an atmospheric lifetime of one week. Carbon dioxide has a lifetime of a century or more, and as such, changes in aerosol concentrations will only delay climate changes due to carbon dioxide.[56]

In addition to their direct effect by scattering and absorbing solar radiation, aerosols have indirect effects on the radiation budget.[57] Sulfate aerosols act as cloud condensation nuclei and thus lead to clouds that have more and smaller cloud droplets. These clouds reflect solar radiation more efficiently than clouds with fewer and larger droplets.[58] This effect also causes droplets to be of more uniform size, which reduces growth of raindrops and makes the cloud more reflective to incoming sunlight.[59] Indirect effects are most noticeable in marine stratiform clouds, and have very little radiative effect on convective clouds. Aerosols, particularly indirect effects, represent the largest uncertainty in radiative forcing.[60]

Soot may cool or warm the surface, depending on whether it is airborne or deposited. Atmospheric soot aerosols directly absorb solar radiation, which heats the atmosphere and cools the surface. In isolated areas with high soot production, such as rural India, as much as 50% of surface warming due to greenhouse gases may be masked by atmospheric brown clouds.[61] Atmospheric soot always contributes additional warming to the climate system. When deposited, especially on glaciers or on ice in arctic regions, the lower surface albedo can also directly heat the surface.[62] The influences of aerosols, including black carbon, are most pronounced in the tropics and sub-tropics, particularly in Asia, while the effects of greenhouse gases are dominant in the extratropics and southern hemisphere.[63]

Solar variation

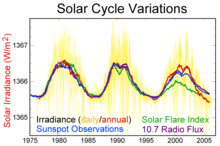

Variations in solar output have been the cause of past climate changes.[64] The consensus among climate scientists is that changes in solar forcing probably had a slight cooling effect in recent decades. This result is less certain than some others, with a few papers suggesting a warming effect.[31][65][66][67]

Greenhouse gases and solar forcing affect temperatures in different ways. While both increased solar activity and increased greenhouse gases are expected to warm the troposphere, an increase in solar activity should warm the stratosphere while an increase in greenhouse gases should cool the stratosphere.[31] Observations show that temperatures in the stratosphere have been cooling since 1979, when satellite measurements became available. Radiosonde (weather balloon) data from the pre-satellite era show cooling since 1958, though there is greater uncertainty in the early radiosonde record.[68]

A related hypothesis, proposed by Henrik Svensmark, is that magnetic activity of the sun deflects cosmic rays that may influence the generation of cloud condensation nuclei and thereby affect the climate.[69] Other research has found no relation between warming in recent decades and cosmic rays.[70][71] The influence of cosmic rays on cloud cover is about a factor of 100 lower than needed to explain the observed changes in clouds or to be a significant contributor to present-day climate change.[72]

Feedback

Feedback is a process in which changing one quantity changes a second quantity, and the change in the second quantity in turn changes the first. Positive feedback amplifies the change in the first quantity while negative feedback reduces it. Feedback is important in the study of global warming because it may amplify or diminish the effect of a particular process. The main positive feedback in global warming is the tendency of warming to increase the amount of water vapor in the atmosphere, a significant greenhouse gas. The main negative feedback is radiative cooling, which increases as the fourth power of temperature; the amount of heat radiated from the Earth into space increases with the temperature of Earth's surface and atmosphere. Imperfect understanding of feedbacks is a major cause of uncertainty and concern about global warming.

Climate models

The main tools for projecting future climate changes are mathematical models based on physical principles including fluid dynamics, thermodynamics and radiative transfer. Although they attempt to include as many processes as possible, simplifications of the actual climate system are inevitable because of the constraints of available computer power and limitations in knowledge of the climate system. All modern climate models are in fact combinations of models for different parts of the Earth. These include an atmospheric model for air movement, temperature, clouds, and other atmospheric properties; an ocean model that predicts temperature, salt content, and circulation of ocean waters; models for ice cover on land and sea; and a model of heat and moisture transfer from soil and vegetation to the atmosphere. Some models also include treatments of chemical and biological processes.[73] Warming due to increasing levels of greenhouse gases is not an assumption of the models; rather, it is an end result from the interaction of greenhouse gases with radiative transfer and other physical processes.[74] Although much of the variation in model outcomes depends on the greenhouse gas emissions used as inputs, the temperature effect of a specific greenhouse gas concentration (climate sensitivity) varies depending on the model used. The representation of clouds is one of the main sources of uncertainty in present-generation models.[75]

Global climate model projections of future climate most often have used estimates of greenhouse gas emissions from the IPCC Special Report on Emissions Scenarios (SRES). In addition to human-caused emissions, some models also include a simulation of the carbon cycle; this generally shows a positive feedback, though this response is uncertain. Some observational studies also show a positive feedback.[76][77][78] Including uncertainties in future greenhouse gas concentrations and climate sensitivity, the IPCC anticipates a warming of 1.1 °C to 6.4 °C (2.0 °F to 11.5 °F) by the end of the 21st century, relative to 1980–1999.[2]

Models are also used to help investigate the causes of recent climate change by comparing the observed changes to those that the models project from various natural and human-derived causes. Although these models do not unambiguously attribute the warming that occurred from approximately 1910 to 1945 to either natural variation or human effects, they do indicate that the warming since 1970 is dominated by man-made greenhouse gas emissions.[31]

The physical realism of models is tested by examining their ability to simulate current or past climates.[79] Current climate models produce a good match to observations of global temperature changes over the last century, but do not simulate all aspects of climate.[42] Not all effects of global warming are accurately predicted by the climate models used by the IPCC. For example, observed Arctic shrinkage has been faster than that predicted.[80]

Attributed and expected effects

Global warming may be detected in natural, ecological or social systems as a change having statistical significance.[81] Attribution of these changes e.g., to natural or human activities, is the next step following detection.[82]

Natural systems

Global warming has been detected in a number of systems. Some of these changes, e.g., based on the instrumental temperature record, have been described in the section on temperature changes. Rising sea levels and observed decreases in snow and ice extent are consistent with warming.[17] Most of the increase in global average temperature since the mid-20th century is, with high probability,[D] atttributable to human-induced changes in greenhouse gas concentrations.[83]

Even with current policies to reduce emissions, global emissions are still expected to continue to grow over the coming decades.[84] Over the course of the 21st century, increases in emissions at or above their current rate would very likely induce changes in the climate system larger than those observed in the 20th century.

In the IPCC Fourth Assessment Report, across a range of future emission scenarios, model-based estimates of sea level rise for the end of the 21st century (the year 2090-2099, relative to 1980-1999) range from 0.18 to 0.59 m. These estimates, however, were not given a likelihood due to a lack of scientific understanding, nor was an upper bound given for sea level rise. Over the course of centuries to millennia, the melting of ice sheets could result in sea level rise of 4–6 m or more.[85]

Changes in regional climate are expected to include greater warming over land, with most warming at high northern latitudes, and least warming over the Southern Ocean and parts of the North Atlantic Ocean.[84] Snow cover area and sea ice extent are expected to decrease. The frequency of hot extremes, heat waves, and heavy precipitation will very likely increase.

Ecological systems

In terrestrial ecosystems, the earlier timing of spring events, and poleward and upward shifts in plant and animal ranges, have been linked with high confidence to recent warming.[17] Future climate change is expected to particularly affect certain ecosystems, including tundra, mangroves, and coral reefs.[84] It is expected that most ecosystems will be affected by higher atmospheric CO2 levels, combined with higher global temperatures.[86] Overall, it is expected that climate change will result in the extinction of many species and reduced diversity of ecosystems.[87]

Social systems

There is some evidence of regional climate change affecting systems related to human activities, including agricultural and forestry management activities at higher latitudes in the Northern Hemisphere.[17] Future climate change is expected to particularly affect some sectors and systems related to human activities.[84] Water resources may be stressed in some dry regions at mid-latitudes, the dry tropics, and areas that depend on snow and ice melt. Reduced water availability may affect agriculture in low latitudes. Low-lying coastal systems are vulnerable to sea level rise and storm surge. Human health in populations with limited capacity to adapt to climate change. It is expected that some regions will be particularly affected by climate change, including the Arctic, Africa, small islands, and Asian and African megadeltas. Some people, such as the poor, young children, and the elderly, are particularly at risk, even in high-income areas.

Responses to global warming

Mitigation

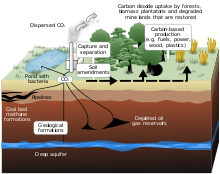

Reducing the amount of future climate change is called mitigation of climate change. The IPCC defines mitigation as activities that reduce greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions, or enhance the capacity of carbon sinks to absorb GHGs from the atmosphere.[88] Many countries, both developing and developed, are aiming to use cleaner, less polluting, technologies.[45]: 192 Use of these technologies aids mitigation and could result in substantial reductions in CO2 emissions. Policies include targets for emissions reductions, increased use of renewable energy, and increased energy efficiency. Studies indicate substantial potential for future reductions in emissions.[89] Since even in the most optimistic scenario, fossil fuels are going to be used for years to come, mitigation may also involve carbon capture and storage, a process that traps CO2 produced by factories and gas or coal power stations and then stores it, usually underground.[90]

Adaptation

Other policy responses include adaptation to climate change. Adaptation to climate change may be planned, e.g., by local or national government, or spontaneous, i.e., done privately without government intervention.[91] The ability to adapt is closely linked to social and economic development.[89] Even societies with high capacities to adapt are still vulnerable to climate change. Planned adaptation is already occurring on a limited basis. The barriers, limits, and costs of future adaptation are not fully understood.

Another policy response is engineering of the climate (geoengineering). This policy response is sometimes grouped together with mitigation.[92] Geoengineering is largely unproven, and reliable cost estimates for it have not yet been published.[93]

UNFCCC

Most countries are Parties to the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC).[94] The ultimate objective of the Convention is to prevent "dangerous" human interference of the climate system.[95] As is stated in the Convention, this requires that GHGs are stabilized in the atmosphere at a level where ecosystems can adapt naturally to climate change, food production is not threatened, and economic development can proceed in a sustainable fashion.

The UNFCCC recognizes differences among countries in their responsibility to act on climate change.[96] In the Kyoto Protocol to the UNFCCC, most developed countries (listed in Annex I of the treaty) took on legally binding commitments to reduce their emissions.[97] Policy measures taken in response to these commitments have reduced emissions.[98] For many developing (non-Annex I) countries, reducing poverty is their overriding aim.[99]

At the 15th UNFCCC Conference of the Parties, held in 2009 at Copenhagen, several UNFCCC Parties produced the Copenhagen Accord.[100] Parties agreeing with the Accord aim to limit the future increase in global mean temperature to below 2 °C.[101]

Views on global warming

There are different views over what the appropriate policy response to climate change should be.[102][103] These competing views weigh the benefits of limiting emissions of greenhouse gases against the costs. In general, it seems likely that climate change will impose greater damages and risks in poorer regions.[104]

Politics

Developing and developed countries have made different arguments over who should bear the burden of costs for cutting emissions. Developing countries often concentrate on per capita emissions, that is, the total emissions of a country divided by its population.[105] Per capita emissions in the industrialized countries are typically as much as ten times the average in developing countries.[106] This is used to make the argument that the real problem of climate change is due to the profligate and unsustainable lifestyles of those living in rich countries.[105] On the other hand, commentators from developed countries more often point out that it is total emissions that matter.[105] In 2008, developing countries made up around half of the world's total emissions of CO2 from cement production and fossil fuel use.[107]

The Kyoto Protocol, which came into force in 2005, sets legally binding emission limitations for most developed countries.[97] Developing countries are not subject to limitations. This exemption led the U.S. and Australia to decide not to ratify the treaty.[108][109] At the time, almost all world leaders expressed their disappointment over President Bush's decision.[109] Australia has since ratified the Kyoto protocol.[110]

Public opinion

In 2007–2008 Gallup Polls surveyed 127 countries. Over a third of the world's population was unaware of global warming, with people in developing countries less aware than those in developed, and those in Africa the least aware. Of those aware, Latin America leads in belief that temperature changes are a result of human activities while Africa, parts of Asia and the Middle East, and a few countries from the Former Soviet Union lead in the opposite belief.[111] In the Western world, opinions over the concept and the appropriate responses are divided. Nick Pidgeon of Cardiff University finds that "results show the different stages of engagement[clarification needed] about global warming on each side of the Atlantic"; where Europe debates the appropriate responses while the United States debates whether climate change is happening.[112][113][vague][dubious – discuss]

Other views

Most scientists accept that humans are contributing to observed climate change.[44][114] National science academies have called on world leaders for policies to cut global emissions.[115] There are, however, some scientists and non-scientists who question aspects of climate change science.[116][117]

Organizations such as the libertarian Competitive Enterprise Institute, conservative commentators, and companies such as ExxonMobil have challenged IPCC climate change scenarios, funded scientists who disagree with the scientific consensus, and provided their own projections of the economic cost of stricter controls.[118][119][120][121] Environmental organizations and public figures have emphasized changes in the current climate and the risks they entail, while promoting adaptation to changes in infrastructural needs and emissions reductions.[122] Some fossil fuel companies have scaled back their efforts in recent years,[123] or called for policies to reduce global warming.[124]

Etymology

The term global warming was probably first used in its modern sense on 8 August 1975 in a science paper by Wally Broecker in the journal Science called "Are we on the brink of a pronounced global warming?".[125][126][127] Broecker's choice of words was new and represented a significant recognition that the climate was warming, previously the phrasing used by scientists was "inadvertent climate modification," because while it was recognized humans could change the climate, no one was sure which direction it was going.[128] The National Academy of Sciences first used global warming in a 1979 paper called the Charney Report, it said: "if carbon dioxide continues to increase, [we find] no reason to doubt that climate changes will result and no reason to believe that these changes will be negligible."[129] The report made a distinction between referring to surface temperature changes as global warming, while referring to other changes caused by increased CO2 as climate change.[128] This distinction is still often used in science reports, with global warming meaning surface temperatures, and climate change meaning other changes (increased storms, etc..)[128]

Global warming became more widely popular after 1988 when NASA scientist James E. Hansen used the term in a testimony to Congress.[128] He said: "global warming has reached a level such that we can ascribe with a high degree of confidence a cause and effect relationship between the greenhouse effect and the observed warming."[130] His testimony was widely reported and afterward global warming was commonly used by the press and in public discourse.[128]

See also

Notes

- ^ Increase is for years 1905 to 2005. Global surface temperature is defined in the IPCC Fourth Assessment Report as the average of near-surface air temperature over land and sea surface temperature. These error bounds are constructed with a 90% confidence interval.

- ^ The 2001 joint statement was signed by the national academies of science of Australia, Belgium, Brazil, Canada, the Caribbean, the People's Republic of China, France, Germany, India, Indonesia, Ireland, Italy, Malaysia, New Zealand, Sweden, and the UK. The 2005 statement added Japan, Russia, and the U.S. The 2007 statement added Mexico and South Africa. The Network of African Science Academies, and the Polish Academy of Sciences have issued separate statements. Professional scientific societies include American Astronomical Society, American Chemical Society, American Geophysical Union, American Institute of Physics, American Meteorological Society, American Physical Society, American Quaternary Association, Australian Meteorological and Oceanographic Society, Canadian Foundation for Climate and Atmospheric Sciences, Canadian Meteorological and Oceanographic Society, European Academy of Sciences and Arts, European Geosciences Union, European Science Foundation, Geological Society of America, Geological Society of Australia, Geological Society of London-Stratigraphy Commission, InterAcademy Council, International Union of Geodesy and Geophysics, International Union for Quaternary Research, National Association of Geoscience Teachers, National Research Council (US), Royal Meteorological Society, and World Meteorological Organization.

- ^ Note that the greenhouse effect produces an average worldwide temperature increase of about 33 °C (59 °F) compared to black body predictions without the greenhouse effect, not an average surface temperature of 33 °C (91 °F). The average worldwide surface temperature is about 14 °C (57 °F).

- ^ In the IPCC Fourth Assessment Report, published in 2007, this attribution is given a probability of greater than 90%, based on expert judgement.[131] According to the US National Research Council Report – Understanding and Responding to Climate Change - published in 2008, "[most] scientists agree that the warming in recent decades has been caused primarily by human activities that have increased the amount of greenhouse gases in the atmosphere."[44]

References

- ^ 2009 Ends Warmest Decade on Record. NASA Earth Observatory Image of the Day, January 22, 2010.

- ^ a b c IPCC (2007-05-04). "Summary for Policymakers" (PDF). Climate Change 2007: The Physical Science Basis. Contribution of Working Group I to the Fourth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change. Retrieved 2009-07-03.

- ^

"Understanding and Responding to Climate Change" (PDF). United States National Academy of Sciences. 2008. Retrieved 30 May 2010.

Most scientists agree that the warming in recent decades has been caused primarily by human activities that have increased the amount of greenhouse gases in the atmosphere.

- ^

Lu, Jian (2007). "Expansion of the Hadley cell under global warming" (PDF). Geophysical Research Letters. 34: L06805. doi:10.1029/2006GL028443.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ IPCC (2007). Climate Change 2007: Synthesis Report. Contribution of Working Groups I, II and III to the Fourth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (Full free text). [Core Writing Team, Pachauri, R.K and Reisinger, A. (eds.)]. Geneva, Switzerland: IPCC.

- ^ "Future Climate Change — Future Ocean Acidification". US Epa. 2006-06-28. Retrieved 2010-08-26.

- ^ "What is Ocean Acidification?". Pmel.noaa.gov. Retrieved 2010-08-26.

- ^ Oreskes, Naomi (December 2004). "BEYOND THE IVORY TOWER: The Scientific Consensus on Climate Change". Science. 306 (5702): 1686. doi:10.1126/science.1103618. PMID 15576594.

Such statements suggest that there might be substantive disagreement in the scientific community about the reality of anthropogenic climate change. This is not the case. [...] Politicians, economists, journalists, and others may have the impression of confusion, disagreement, or discord among climate scientists, but that impression is incorrect.

- ^ "Joint Science Academies' Statement" (PDF). Retrieved 2010-08-09.

- ^ "Understanding and Responding to Climate Change" (PDF). Retrieved 2010-08-09.

- ^ "Article 2". The United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change. Retrieved 15 November 2005.

Such a level should be achieved within a time-frame sufficient to allow ecosystems to adapt naturally to climate change, to ensure that food production is not threatened and to enable economic development to proceed in a sustainable manner

- ^ "Kyoto Protocol: Status of Ratification" (PDF). United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change. 2009-01-14. Retrieved 2009-05-06.

- ^ Joint science academies’ statement (16 May 2007). "Joint science academies' statement: sustainability, energy efficiency and climate protection". UK Royal Society website. Retrieved 2010-04-17.

{{cite web}}:|author=has generic name (help) - ^

NRC (2008). "Understanding and Responding to Climate Change" (PDF). Board on Atmospheric Sciences and Climate, US National Academy of Sciences. p. 4. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2008-08-04. Retrieved 2009-05-20.

{{cite web}}: External link in|publisher= - ^ Slingo, J. (n.d.). "Explaining the evidence of climate change". UK Met Office website. Retrieved 2010-04-17.

- ^ USGRCP (n.d.). "Key Findings. On (website): Global Climate Change Impacts in the United States". U.S. Global Change Research Program website. Retrieved 2010-04-17.

- ^ a b c d IPCC (2007). "1. Observed changes in climate and their effects. In (section): Summary for Policymakers. In (book): Climate Change 2007: Synthesis Report. Contribution of Working Groups I, II and III to the Fourth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (Core Writing Team, Pachauri, R.K and Reisinger, A. (eds.))". Book publisher: IPCC, Geneva, Switzerland. This version: IPCC website. Retrieved 2010-04-17.

- ^ Trenberth, Kevin E. (2007). "Chapter 3: Observations: Surface and Atmospheric Climate Change". IPCC Fourth Assessment Report (PDF). Cambridge, United Kingdom and New York, NY, USA: Cambridge University Press. p. 244.

{{cite book}}: External link in|chapterurl=|chapterurl=ignored (|chapter-url=suggested) (help); Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ Jansen, E., J. Overpeck; Briffa, K.R.; Duplessy, J.-C.; Joos, F.; Masson-Delmotte, V.; Olago, D.; Otto-Bliesner, B.; Peltier, W.R.; Rahmstorf, S.; Ramesh, R.; Raynaud, D.; Rind, D.; Solomina, O.; Villalba; Zhang, R. (2007-02-11). "Palaeoclimate". In Marquis, S.; Qin, D.; Manning, Z.; Chen, M.; Tignor, M.; Miller, H.L. (eds.). Climate Change 2007: The Physical Science Basis : contribution of Working Group I to the Fourth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change. IPCC Fourth Assessment Report. Cambridge and New York: Cambridge University Press. pp. 466–478. ISBN 978-0521705967. OCLC 132298563.

{{cite book}}:|editor6-first=missing|editor6-last=(help);|first16=missing|last16=(help); External link in|chapterurl=|editor6=(help); More than one of|editor1-last=and|editor-last=specified (help); Unknown parameter|chapterurl=ignored (|chapter-url=suggested) (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Hansen, James E. (2006-01-12). "Goddard Institute for Space Studies, GISS Surface Temperature Analysis". NASA Goddard Institute for Space Studies. Retrieved 2007-01-17.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ "NOAA/NCDC 2009 climate". Retrieved 2010-02-15.

- ^ "Global Temperature for 2005: second warmest year on record" (PDF). Climatic Research Unit, School of Environmental Sciences, University of East Anglia. 2005-12-15. Archived from the original (PDF) on April 17, 2007. Retrieved 2007-04-13.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ "WMO statement on the status of the global climate in 2005" (PDF). World Meteorological Organization. 2005-12-15. Retrieved 2009-04-24.

- ^ Changnon, Stanley A. (2000). El Niño, 1997–1998: The Climate Event of the Century. London: Oxford University Press. ISBN 0195135520.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ Knight, J.; Kenney, J.J.; Folland, C.; Harris, G.; Jones, G.S.; Palmer, M.; Parker, D.; Scaife, A.; Stott, P. (August 2009). "Do Global Temperature Trends Over the Last Decade Falsify Climate Predictions? [in "State of the Climate in 2008"]" (PDF). Bull.Amer.Meteor.Soc. 90 (8): S75–S79. Retrieved 2009-09-08.

- ^ Global temperature slowdown — not an end to climate change. UK Met Office. Retrieved 2009-09-08.

- ^ "IPCC Fourth Assessment Report, Chapter 3" (PDF). 2007-02-05. p. 237. Retrieved 2009-03-14.

- ^ Rowan T. Sutton, Buwen Dong, Jonathan M. Gregory (2007). "Land/sea warming ratio in response to climate change: IPCC AR4 model results and comparison with observations". Geophysical Research Letters. 34: L02701. doi:10.1029/2006GL028164. Retrieved 2007-09-19.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (2001). "Atmospheric Chemistry and Greenhouse Gases". Climate Change 2001: The Scientific Basis. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0521014956.

{{cite book}}: External link in|chapterurl=|chapterurl=ignored (|chapter-url=suggested) (help) - ^ Meehl, Gerald A. (2005-03-18). "How Much More Global Warming and Sea Level Rise" (PDF). Science. 307 (5716): 1769–1772. doi:10.1126/science.1106663. PMID 15774757. Retrieved 2007-02-11.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ a b c d

Hegerl, Gabriele C. (2007). "Understanding and Attributing Climate Change" (PDF). Climate Change 2007: The Physical Science Basis. Contribution of Working Group I to the Fourth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change. IPCC.

Recent estimates indicate a relatively small combined effect of natural forcings on the global mean temperature evolution of the second half of the 20th century, with a small net cooling from the combined effects of solar and volcanic forcings.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ Weart, Spencer (2008). "The Carbon Dioxide Greenhouse Effect". The Discovery of Global Warming. American Institute of Physics. Retrieved 21 April 2009.

- ^ IPCC (2007). "Chapter 1: Historical Overview of Climate Change Science" (PDF). IPCC WG1 AR4 Report. IPCC. pp. p97 (PDF page 5 of 36). Retrieved 21 April 2009.

To emit 240 W m–2, a surface would have to have a temperature of around −19 °C. This is much colder than the conditions that actually exist at the Earth's surface (the global mean surface temperature is about 14 °C). Instead, the necessary −19 °C is found at an altitude about 5 km above the surface.

{{cite web}}:|pages=has extra text (help) - ^ Kiehl, J.T.; Trenberth, K.E. (1997). "Earth's Annual Global Mean Energy Budget" (PDF). Bulletin of the American Meteorological Society. 78 (2): 197–208. doi:10.1175/1520-0477(1997)078<0197:EAGMEB>2.0.CO;2. Retrieved 21 April 2009.

- ^ Schmidt, Gavin (6 Apr 2005). "Water vapour: feedback or forcing?". RealClimate. Retrieved 21 April 2009.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: year (link) - ^ Russell, Randy (May 16, 2007). "The Greenhouse Effect & Greenhouse Gases". University Corporation for Atmospheric Research Windows to the Universe. Retrieved Dec 27, 2009.

- ^ EPA (2007). "Recent Climate Change: Atmosphere Changes". Climate Change Science Program. United States Environmental Protection Agency. Retrieved 21 April 2009.

- ^ Spahni, Renato (November 2005). "Atmospheric Methane and Nitrous Oxide of the Late Pleistocene from Antarctic Ice Cores". Science. 310 (5752): 1317–1321. doi:10.1126/science.1120132. PMID 16311333. Retrieved 27 December 2009.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ Siegenthaler, Urs (November 2005). "Stable Carbon Cycle–Climate Relationship During the Late Pleistocene" (PDF). Science. 310 (5752): 1313–1317. doi:10.1126/science.1120130. PMID 16311332. Retrieved 25 August 2010.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ Petit, J. R. (3 June 1999). "Climate and atmospheric history of the past 420,000 years from the Vostok ice core, Antarctica" (PDF). Nature. 399 (6735): 429–436. doi:10.1038/20859. Retrieved 27 December 2009.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ Pearson, PN; Palmer, MR (2000). "Atmospheric carbon dioxide concentrations over the past 60 million years". Nature. 406 (6797): 695–699. doi:10.1038/35021000. PMID 10963587.

{{cite journal}}: More than one of|author=and|last1=specified (help) - ^ a b IPCC (2001). "Summary for Policymakers" (PDF). Climate Change 2001: The Scientific Basis. Contribution of Working Group I to the Third Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change. IPCC. Retrieved 21 April 2009.

- ^ Rogner et al., 2007. 1.3.1.2 Intensities

- ^ a b c

NRC (2008). "Understanding and Responding to Climate Change" (PDF). Board on Atmospheric Sciences and Climate, US National Academy of Sciences. p. 2. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2008-08-04. Retrieved 2009-05-20.

{{cite web}}: External link in|publisher= - ^ a b World Bank (2010). World Development Report 2010: Development and Climate Change. The International Bank for Reconstruction and Development / The World Bank, 1818 H Street NW, Washington DC 20433. doi:10.1596/978-0-8213-7987-5. ISBN 9780821379875. Retrieved 2010-04-06.

- ^ Fisher, B.S., N. Nakicenovic, K. Alfsen, J. Corfee Morlot, F. de la Chesnaye, J.-Ch. Hourcade, K. Jiang, M. Kainuma, E. La Rovere, A. Matysek, A. Rana, K. Riahi, R. Richels, S. Rose, D. van Vuuren, R. Warren (2007). 3.1 Emissions scenarios. In (book chapter): Issues related to mitigation in the long term context. In: Climate Change 2007: Mitigation. Contribution of Working Group III to the Fourth Assessment Report of the Inter-governmental Panel on Climate Change (B. Metz, O.R. Davidson, P.R. Bosch, R. Dave, L.A. Meyer (eds)). Print version: Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, United Kingdom and New York, NY, USA. This version: IPCC website. ISBN 9780521705981. Retrieved 2010-06-19.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Morita, T. and J. Robertson (co-ordinating lead authors). A. Adegbulugbe, J. Alcamo, D. Herbert, E.L.L. Rovere, N. Nakicenovic, H. Pitcher, P. Raskin, K. Riahi, A. Sankovski, V. Sokolov, B. de Vries, and D. Zhou (lead authors). K. Jiang, Ton Manders, Y. Matsuoka, S. Mori, A. Rana, R.A. Roehrl, K.E. Rosendahl, and K. Yamaji (contributing authors). M. Chadwick and J. Parikh (review editors) (2001). 2.5.1.4 Emissions and Other Results of the SRES Scenarios. In (book chapter): 2. Greenhouse Gas Emission Mitigation Scenarios and Implications. In: Climate Change 2001: Mitigation. Contribution of Working Group III to the Third Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (B. Metz, O. Davidson, R. Swart, and J. Pan (eds.)). Print version: Cambridge University Press. This version: GRID-Arendal website. doi:10.2277/0521807697. ISBN 9780521807692. Retrieved 2010-06-19.

{{cite book}}:|author=has generic name (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Rogner et al., 2007, Figure 1.7

- ^ Prentice, I.C. (co-ordinating lead author). G.D. Farquhar, M.J.R. Fasham, M.L. Goulden, M. Heimann, V.J. Jaramillo, H.S. Kheshgi, C. Le Quéré, R.J. Scholes, D.W.R. Wallace (lead authors). D. Archer, M.R. Ashmore, O. Aumont, D. Baker, M. Battle, M. Bender, L.P. Bopp, P. Bousquet, K. Caldeira, P. Ciais, P.M. Cox, W. Cramer, F. Dentener, I.G. Enting, C.B. Field, P. Friedlingstein, E.A. Holland, R.A. Houghton, J.I. House, A. Ishida, A.K. Jain, I.A. Janssens, F. Joos, T. Kaminski, C.D. Keeling, R.F. Keeling, D.W. Kicklighter, K.E. Kohfeld, W. Knorr, R. Law, T. Lenton, K. Lindsay, E. Maier-Reimer, A.C. Manning, R.J. Matear, A.D. McGuire, J.M. Melillo, R. Meyer, M. Mund, J.C. Orr, S. Piper, K. Plattner, P.J. Rayner, S. Sitch, R. Slater, S. Taguchi, P.P. Tans, H.Q. Tian, M.F. Weirig, T. Whorf, A. Yool (contributing authors). L. Pitelka, A. Ramirez Rojas (review editors) (2001). Executive Summary. In (book chapter): 3. The Carbon Cycle and Atmospheric Carbon Dioxide. In: Climate Change 2001: The Scientific Basis. Contribution of Working Group I to the Third Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (J.T. Houghton, Y. Ding, D.J. Griggs, M. Noguer, P.J. van der Linden, X. Dai, K. Maskell, C.A. Johnson (eds)). Print version: Cambridge University Press. This version: GRID-Arendal website. ISBN 9780521807678. Retrieved 2010-06-19.

{{cite book}}:|author=has generic name (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Nakicenovic., N.; et al. (2001). "An Overview of Scenarios: Resource Availability". IPCC Special Report on Emissions Scenarios. IPCC. Retrieved 21 April 2009.

{{cite web}}: Explicit use of et al. in:|author=(help) - ^ Ramaswamy, V.; Schwarzkopf, M.D.; Shine, K.P. (1992). "Radiative forcing of climate from halocarbon-induced global stratospheric ozone loss". Nature. 355: 810–812. doi:10.1038/355810a0.

- ^ Sparling, Brien (May 30, 2001). "Ozone Depletion, History and politics". NASA. Retrieved 2009-02-15.

- ^ Shindell, Drew; Faluvegi, Greg; Lacis, Andrew; Hansen, James; Ruedy, Reto; Aguilar, Elliot (2006). "Role of tropospheric ozone increases in 20th-century climate change". Journal of Geophysical Research. 111: D08302. doi:10.1029/2005JD006348.

- ^ Mitchell, J.F.B.; et al. (2001). "Detection of Climate Change and Attribution of Causes: Space-time studies". Climate Change 2001: The Scientific Basis. Contribution of Working Group I to the Third Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change. IPCC. Retrieved 21 April 2009.

{{cite web}}: Explicit use of et al. in:|author=(help) - ^ Hansen, J; Sato, M; Ruedy, R; Lacis, A; Oinas, V (2000). "Global warming in the twenty-first century: an alternative scenario". Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 97 (18): 9875–80. doi:10.1073/pnas.170278997. PMC 27611. PMID 10944197.

{{cite journal}}: More than one of|author=and|last1=specified (help) - ^ Ramanathan, V.; Carmichael, G. (2008). "Global and regional climate changes due to black carbon". Nature Geosciences. 1: 221–227. doi:10.1038/ngeo156.

- ^ Lohmann, U. & J. Feichter (2005). "Global indirect aerosol effects: a review". Atmos. Chem. Phys. 5: 715–737. doi:10.5194/acp-5-715-2005.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: unflagged free DOI (link) - ^ Twomey, S. (1977). "Influence of pollution on shortwave albedo of clouds". J. Atmos. Sci. 34: 1149–1152. doi:10.1175/1520-0469(1977)034<1149:TIOPOT>2.0.CO;2.

- ^ Albrecht, B. (1989). "Aerosols, cloud microphysics, and fractional cloudiness". Science. 245 (4923): 1227–1239. doi:10.1126/science.245.4923.1227. PMID 17747885.

- ^ IPCC, 2007: Summary for Policymakers. In: Climate Change 2007: The Physical Science Basis. Contribution of Working Group I to the Fourth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change [Solomon, S., D. Qin, M. Manning, Z. Chen, M. Marquis, K.B. Averyt, M.Tignor and H.L. Miller (eds.)]. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, United Kingdom and New York, NY, USA.

- ^ Ramanathan, V.; Chung, C; Kim, D; Bettge, T; Buja, L; Kiehl, JT; Washington, WM; Fu, Q; Sikka, DR (2005). "Atmospheric brown clouds: Impacts on South Asian climate and hydrological cycle". Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 102 (15): 5326–5333. doi:10.1073/pnas.0500656102. PMC 552786. PMID 15749818.

{{cite journal}}: More than one of|first1=and|first=specified (help); More than one of|last1=and|last=specified (help); Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ Ramanathan, V.; et al. (2008). "Report Summary" (PDF). Atmospheric Brown Clouds: Regional Assessment Report with Focus on Asia. United Nations Environment Programme.

{{cite web}}: Explicit use of et al. in:|author=(help) - ^ Ramanathan, V.; et al. (2008). "Part III: Global and Future Implications" (PDF). Atmospheric Brown Clouds: Regional Assessment Report with Focus on Asia. United Nations Environment Programme.

{{cite web}}: Explicit use of et al. in:|author=(help) - ^ National Research Council (1994). Solar Influences On Global Change. Washington, D.C.: National Academy Press. p. 36. ISBN 0-309-05148-7.

- ^ Duffy, Santer and Wigley, "Solar variability does not explain late-20th-century warming" Physics Today, January, 2009, pp 48-49. The authors respond to recent assertions by Nicola Scafetta and Bruce West that solar forcing "might account" for up to about half of 20th-century warming.

- ^ Hansen, J. (2002). "Climate". Journal of Geophysical Research. 107: 4347. doi:10.1029/2001JD001143.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|unused_data=ignored (help) - ^ Hansen, J. (2005). "Efficacy of climate forcings". Journal of Geophysical Research. 110: D18104. doi:10.1029/2005JD005776.

- ^ Randel, William J.; Shine, Keith P.; Austin, John; Barnett, John; Claud, Chantal; Gillett, Nathan P.; Keckhut, Philippe; Langematz, Ulrike; Lin, Roger (2009). "An update of observed stratospheric temperature trends". Journal of Geophysical Research. 114: D02107. doi:10.1029/2008JD010421.

- ^ Marsh, Nigel (November 2000). "Cosmic Rays, Clouds, and Climate" (PDF). Space Science Reviews. 94 (1–2): 215–230. doi:10.1023/A:1026723423896. Retrieved 2007-04-17.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ Lockwood, Mike (2007). "Recent oppositely directed trends in solar climate forcings and the global mean surface air temperature" (PDF). Proceedings of the Royal Society A. 463: 2447. doi:10.1098/rspa.2007.1880. Archived from the original (PDF) on September 26, 2007. Retrieved 2007-07-21.

Our results show that the observed rapid rise in global mean temperatures seen after 1985 cannot be ascribed to solar variability, whichever of the mechanisms is invoked and no matter how much the solar variation is amplified

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help); Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ T Sloan and A W Wolfendale (2008). "Testing the proposed causal link between cosmic rays and cloud cover". Environ. Res. Lett. 3: 024001. doi:10.1088/1748-9326/3/2/024001.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|DUPLICATE DATA: page=ignored (help) - ^ Pierce, J.R. and P.J. Adams (2009). "Can cosmic rays affect cloud condensation nuclei by altering new particle formation rates?". Geophysical Research Letters. 36: L09820. doi:10.1029/2009GL037946.

- ^ Denman, K.L.; et al. (2007). "Chapter 7, Couplings Between Changes in the Climate System and Biogeochemistry" (PDF). Fourth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change. IPCC. Retrieved 2008-02-21.

{{cite web}}: Explicit use of et al. in:|author=(help) - ^ Hansen, James (2000). Climatic Change: Understanding Global Warming. Health Press. ISBN 9780929173337. Retrieved 2007-08-18.

{{cite book}}:|work=ignored (help) - ^ Stocker, Thomas F. (2001). "7.2.2 Cloud Processes and Feedbacks". Climate Change 2001: The Scientific Basis. Contribution of Working Group I to the Third Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change. IPCC. Retrieved 2007-03-04.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ Torn, Margaret (2006). "Missing feedbacks, asymmetric uncertainties, and the underestimation of future warming". Geophysical Research Letters. 33 (10): L10703. doi:10.1029/2005GL025540. L10703. Retrieved 2007-03-04.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ Harte, John (2006). "Shifts in plant dominance control carbon-cycle responses to experimental warming and widespread drought". Environmental Research Letters. 1 (1): 014001. doi:10.1088/1748-9326/1/1/014001. 014001. Retrieved 2007-05-02.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ Scheffer, Marten (2006). "Positive feedback between global warming and atmospheric CO2 concentration inferred from past climate change" (PDF). Geophysical Research Letters. 33: L10702. doi:10.1029/2005gl025044. Retrieved 2007-05-04.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ Randall, D.A.; et al. (2007). "Chapter 8, Climate Models and Their Evaluation" (PDF). Fourth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change. IPCC. Retrieved 2009-03-21.

{{cite web}}: Explicit use of et al. in:|author=(help) - ^ Stroeve, J.; et al. (2007). "Arctic sea ice decline: Faster than forecast". Geophysical Research Letters. 34: L09501. doi:10.1029/2007GL029703.

{{cite journal}}: Explicit use of et al. in:|author=(help) - ^ IPCC (2007d). "1.1 Observations of climate change. In (section): Synthesis Report. In (book): Climate Change 2007: Synthesis Report. Contribution of Working Groups I, II and III to the Fourth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (Core Writing Team, Pachauri, R.K and Reisinger, A. (eds.))". Book version: IPCC, Geneva, Switzerland. This version: IPCC website. Retrieved 2010-04-26.

- ^ IPCC (2007d). "2.4 Attribution of climate change. In (section): Synthesis Report. In (book): Climate Change 2007: Synthesis Report. Contribution of Working Groups I, II and III to the Fourth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (Core Writing Team, Pachauri, R.K and Reisinger, A. (eds.))". Book version: IPCC, Geneva, Switzerland. This version: IPCC website. Retrieved 2010-04-26.

- ^ IPCC (2007d). "2. Causes of change. In (section): Summary for Policymakers. In (book): Climate Change 2007: Synthesis Report. Contribution of Working Groups I, II and III to the Fourth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (Core Writing Team, Pachauri, R.K and Reisinger, A. (eds.))". Book version: IPCC, Geneva, Switzerland. This version: IPCC website. Retrieved 2010-04-26.

- ^ a b c d IPCC (2007d). "3. Projected climate change and its impacts. In (section): Summary for Policymakers. In (book): Climate Change 2007: Synthesis Report. Contribution of Working Groups I, II and III to the Fourth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (Core Writing Team, Pachauri, R.K and Reisinger, A. (eds.))". Book version: IPCC, Geneva, Switzerland. This version: IPCC website. Retrieved 2010-04-26.

- ^ IPCC (2007b). "Magnitudes of impact. In (section): Summary for Policymakers. In (book): Climate Change 2007: Impacts, Adaptation and Vulnerability. Contribution of Working Group II to the Fourth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (M.L. Parry, O.F. Canziani, J.P. Palutikof, P.J. van der Linden and C.E. Hanson, Eds.)". Book version: Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, UK. This version: IPCC website. Retrieved 2010-04-26.

- ^

Fischlin, A., G.F. Midgley, J.T. Price, R. Leemans, B. Gopal, C. Turley, M.D.A. Rounsevell, O.P. Dube, J. Tarazona, A.A. Velichko (2007). "Executive Summary. In (book chapter): Ecosystems, their properties, goods and services. In: Climate Change 2007: Impacts, Adaptation and Vulnerability. Contribution of Working Group II to the Fourth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (M.L. Parry, O.F. Canziani, J.P. Palutikof, P.J. van der Linden and C.E. Hanson, Eds.)" (PDF). Book version: Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, UK. This version: IPCC website. p. 213. Retrieved 2010-04-26.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^

Schneider, S.H., S. Semenov, A. Patwardhan, I. Burton, C.H.D. Magadza, M. Oppenheimer, A.B. Pittock, A. Rahman, J.B. Smith, A. Suarez and F. Yamin (2007). "19.3.4 Ecosystems and biodiversity. In (book chapter): Assessing Key Vulnerabilities and the Risk from Climate Change. In: Climate Change 2007: Impacts, Adaptation and Vulnerability. Contribution of Working Group II to the Fourth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (M.L. Parry, O.F. Canziani, J.P. Palutikof, P.J. van der Linden and C.E. Hanson, Eds.)". Book version: Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, UK. This version: IPCC website. Retrieved 2010-04-26.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Verbruggen, A. (ed.) (2007). Glossary J-P. In (book section): Annex I. In: Climate Change 2007: Mitigation. Contribution of Working Group III to the Fourth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (B. Metz, O.R. Davidson, P.R. Bosch, R. Dave, L.A. Meyer (eds.)). Print version: Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, U.K., and New York, N.Y., U.S.A.. This version: IPCC website. ISBN 9780521880114. Retrieved 2010-04-23.

{{cite book}}:|author=has generic name (help) - ^ a b IPCC (2007). 4. Adaptation and mitigation options. In (book section): Summary for Policymakers. In: Climate Change 2007: Synthesis Report. Contribution of Working Groups I, II and III to the Fourth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (Core Writing Team, Pachauri, R.K and Reisinger, A. (eds.)). Print version: IPCC, Geneva, Switzerland. This version: IPCC website. ISBN 9291691224. Retrieved 2010-04-26.

- ^ Robinson, Simon (2010-01-22). "How to reduce Carbon emmissions: Capture and Store It?". Time.com. Retrieved 2010-08-09.

- ^ Smit, B. and O. Pilifosova. Lead Authors: I. Burton, B. Challenger, S. Huq, R.J.T. Klein, G. Yohe. Contributing Authors: N. Adger, T. Downing, E. Harvey, S. Kane, M. Parry, M. Skinner, J. Smith, J. Wandel. Review Editors: A. Patwardhan and J.-F. Soussana (2001). 18.2.3. Adaptation Types and Forms. In (book chapter): Adaptation to Climate Change in the Context of Sustainable Development and Equity. In: Climate Change 2001: Impacts, Adaptation and Vulnerability. Contribution of Working Group II to the Third Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (J.J. McCarthy, O.F. Canziani, N.A. Leary, D.J. Dokken, K.S. White (eds.)). Print version: Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, U.K., and New York, N.Y., U.S.A.. This version: GRID-Arendal website. ISBN 0521807689. Retrieved 2010-01-10.

{{cite book}}:|author=has generic name (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Barker, T., I. Bashmakov, A. Alharthi, M. Amann, L. Cifuentes, J. Drexhage, M. Duan, O. Edenhofer, B. Flannery, M. Grubb, M. Hoogwijk, F. I. Ibitoye, C. J. Jepma, W.A. Pizer, K. Yamaji (2007). 11.2.2 Ocean fertilization and other geo-engineering options. In (book chapter): Mitigation from a cross-sectoral perspective. In: Climate Change 2007: Mitigation. Contribution of Working Group III to the Fourth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (B. Metz, O.R. Davidson, P.R. Bosch, R. Dave, L.A. Meyer (eds)). Print version: Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, U.K., and New York, N.Y., U.S.A.. This version: IPCC website. ISBN 9780521880114. Retrieved 2010-04-05.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ IPCC (2007). C. Mitigation in the short and medium term (until 2030). In (book section): Summary for Policymakers. In: Climate Change 2007: Mitigation. Contribution of Working Group III to the Fourth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (B. Metz, O.R. Davidson, P.R. Bosch, R. Dave, L.A. Meyer (eds)). Print version: Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, U.K., and New York, N.Y., U.S.A.. This version: IPCC website. ISBN 9780521880114. Retrieved 2010-05-15.

- ^ UNFCCC (n.d.). "Essential Background". UNFCCC website. Retrieved 2010-05-18.

- ^ UNFCCC (n.d.). "Full text of the Convention, Article 2". UNFCCC website. Retrieved 2010-05-18.

- ^ UNFCCC (n.d.). "Full text of the Convention, start". UNFCCC website. Retrieved 2010-05-18.

- ^ a b Liverman, D.M. (2008). "Conventions of climate change: constructions of danger and the dispossession of the atmosphere" (PDF). Journal of Historical Geography. 35: 12–14. doi:10.1016/j.jhg.2008.08.008. Retrieved 2009-08-08.

- ^ UNFCCC (19 November 2007). "Compilation and synthesis of fourth national communications. Executive summary. Note by the secretariat. Document code: FCCC/SBI/2007/INF.6". United Nations Office at Geneva, Switzerland. p. 11. Retrieved 2010-05-17.

- ^ UNFCCC (25 October 2005). "Sixth compilation and synthesis of initial national communications from Parties not included in Annex I to the Convention. Note by the secretariat. Executive summary. Document code: FCCC/SBI/2005/18". United Nations Office at Geneva, Switzerland. p. 6. Retrieved 2010-05-17.

- ^ Müller, Benito (February 2010). Copenhagen 2009: Failure or final wake-up call for our leaders? EV 49 (PDF). Dr Benito Müller's web page on the Oxford Institute for Energy Studies website. p. i. ISBN 978190755046. Retrieved 2010-05-18.

{{cite book}}: Check|isbn=value: length (help) - ^ UNFCCC (30 March 2010). "Decision 2/CP. 15 Copenhagen Accord. In: Report of the Conference of the Parties on its fifteenth session, held in Copenhagen from 7 to 19 December 2009. Addendum. Part Two: Action taken by the Conference of the Parties at its fifteenth session" (PDF). United Nations Office at Geneva, Switzerland. p. 5. Retrieved 2010-05-17.

- ^

Rogner, H.-H., D. Zhou, R. Bradley. P. Crabbé, O. Edenhofer, B.Hare, L. Kuijpers, M. Yamaguchi (2007). "Executive Summary. In (book chapter): Introduction. In: Climate Change 2007: Mitigation. Contribution of Working Group III to the Fourth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (B. Metz, O.R. Davidson, P.R. Bosch, R. Dave, L.A. Meyer (eds))". Print version: Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, United Kingdom and New York, NY, USA. Web version: IPCC website. Retrieved 2010-05-05.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Banuri, T., K. Göran-Mäler, M. Grubb, H.K. Jacobson and F. Yamin (1996). Equity and Social Considerations. In: Climate Change 1995: Economic and Social Dimensions of Climate Change. Contribution of Working Group III to the Second Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (J.P. Bruce, H. Lee and E.F. Haites, (eds.)) (PDF). This version: Printed by Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, U.K., and New York, N.Y., U.S.A.. PDF version: IPCC website. p. 87. doi:10.2277/0521568544. ISBN 9780521568548.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Banuri et al., 1996, p. 83

- ^ a b c Banuri et al., 1996, pp. 94-95

- ^ Grubb, M. (July–September 2003). "The Economics of the Kyoto Protocol" (PDF). World Economics. 4 (3): 144. Retrieved 2010-03-25.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: date format (link) - ^ PBL (25 June 2009). "Global CO2 emissions: annual increase halves in 2008". Netherlands Environmental Assessment Agency (PBL) website. Retrieved 2010-05-05.

- ^

IEA (2005). "Energy Policies of IEA Countries — Australia- 2005 Review". International Energy Agency (IEA), Head of Publications Service,

9 rue de la Fédération, 75739 Paris Cedex 15, France. p. 51. Retrieved 2010-04-29.

{{cite web}}: line feed character in|publisher=at position 65 (help) - ^ a b Dessai, S. (2001). "The climate regime from The Hague to Marrakech: Saving or sinking the Kyoto Protocol? Tyndall Centre Working Paper 12". Tyndall Centre website. pp. 5–6. Retrieved 2010-05-05.

- ^ UNFCCC (20 January 2009). "Report of the in-depth review of the fourth national assessment communication of Australia". United Nations Office at Geneva, Switzerland. p. 3. Retrieved 2010-05-05.

- ^ Pelham, Brett (2009-04-22). "Awareness, Opinions About Global Warming Vary Worldwide". Gallup. Retrieved 2009-07-14.

- ^ "Summary of Findings". Little Consensus on Global Warming. Partisanship Drives Opinion. Pew Research Center. 2006-07-12. Retrieved 2007-04-14.

- ^ Crampton, Thomas (2007-01-04). "More in Europe worry about climate than in U.S., poll shows". The New York Times. Retrieved 2010-06-09.

- ^ Wallace, D. and J. Houghton (March 2005). "A guide to facts and fictions about climate change". UK Royal Society website. pp. 3–4. Retrieved 2010-05-05.

- ^ Academia Brasileira de Ciéncias (Brazil), Royal Society of Canada, Chinese Academy of Sciences, Académie des Sciences (France), Deutsche Akademie der Naturforscher Leopoldina (Germany), Indian National Science Academy, Accademia Nazionale dei Lincei (Italy), Science Council of Japan, Academia Mexicana de Ciencias, Russian Academy of Sciences, Academy of Science of South Africa, Royal Society (United Kingdom), National Academy of Sciences (United States of America) (May 2009). "G8+5 Academies' joint statement: Climate change and the transformation of energy technologies for a low carbon future" (PDF). US National Academies website. Retrieved 2010-05-05.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Weart, S. (July 2009). "The Public and Climate Change (cont. – since 1980). Section: After 1988". American Institute of Physics website. Retrieved 2010-05-05.

- ^ SEPP (n.d.). "Frequently Asked Questions About Climate Change". Science & Environmental Policy Project (SEPP) website. Retrieved 2010-05-05.

- ^ Begley, Sharon (2007-08-13). "The Truth About Denial". Newsweek. Retrieved 2007-08-13.

- ^ Adams, David (2006-09-20). "Royal Society tells Exxon: stop funding climate change denial". London: The Guardian. Retrieved 2007-08-09.

- ^ "Exxon cuts ties to global warming skeptics". MSNBC. 2007-01-12. Retrieved 2007-05-02.

- ^ Sandell, Clayton (2007-01-03). "Report: Big Money Confusing Public on Global Warming". ABC. Retrieved 2007-04-27.

- ^ "New Report Provides Authoritative Assessment of National, Regional Impacts of Global Climate Change" (PDF) (Press release). U.S. Global Change Research Program. June 6, 2009. Retrieved 2009-06-27.

- ^ Reuters (May 18, 2007). "Greenpeace: Exxon still funding climate skeptics". USA Today. Retrieved Jan 21, 2010.

{{cite news}}:|author=has generic name (help) - ^ "Global Warming Resolutions at U.S. Oil Companies Bring Policy Commitments from Leaders, and Record High Votes at Laggards" (Press release). Ceres. May 13, 2004. Retrieved 2010-03-04.

- ^ Stefan (28 July 2010). "Happy 35th birthday, global warming!". RealClimate. Retrieved 10 August 2010.

[Broecker's article is] the first of over 10,000 papers for this search term according to the ISI database of journal articles

- ^ Johnson, Brad (3 August 2010). "Wally's World". Foreign Policy. Retrieved 10 August 2010.

- ^ Wallace Broecker, "Climatic Change: Are We on the Brink of a Pronounced Global Warming?" Science, vol. 189 (8 August 1975), 460-463.

- ^ a b c d e Erik Conway. "What's in a Name? Global Warming vs. Climate Change", NASA, December 5, 2008

- ^ National Academy of Science, Carbon Dioxide and Climate, Washington, D.C., 1979, p. vii.

- ^ U.S. Senate, Committee on Energy and Natural Resources, "Greenhouse Effect and Global Climate Change, part 2" 100th Cong., 1st sess., 23 June 1988, p. 44.

- ^ IPCC (2007d). "Introduction. In (section): Synthesis Report. In (book): Climate Change 2007: Synthesis Report. Contribution of Working Groups I, II and III to the Fourth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (Core Writing Team, Pachauri, R.K and Reisinger, A. (eds.))". Book version: IPCC, Geneva, Switzerland. This version: IPCC website. Retrieved 2010-04-26.

Further reading

- Association of British Insurers (2005–06). Financial Risks of Climate Change (PDF).

{{cite book}}: Check date values in:|year=(help) - Ammann, Caspar (2007). "Solar influence on climate during the past millennium: Results from transient simulations with the NCAR Climate Simulation Model" (PDF). Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 104 (10): 3713–3718. doi:10.1073/pnas.0605064103. PMC 1810336. PMID 17360418.

Simulations with only natural forcing components included yield an early 20th century peak warming of ≈0.2 °C (≈1950 AD), which is reduced to about half by the end of the century because of increased volcanism

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - Barnett, Tim P.; Adam, JC; Lettenmaier, DP (2005-11-17). "Potential impacts of a warming climate on water availability in snow-dominated regions" (abstract). Nature. 438 (7066): 303–309. doi:10.1038/nature04141. PMID 16292301.

{{cite journal}}: More than one of|first1=and|first=specified (help); More than one of|last1=and|last=specified (help); Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - Behrenfeld, Michael J.; O'malley, RT; Siegel, DA; Mcclain, CR; Sarmiento, JL; Feldman, GC; Milligan, AJ; Falkowski, PG; Letelier, RM (2006-12-07). "Climate-driven trends in contemporary ocean productivity" (PDF). Nature. 444 (7120): 752–755. doi:10.1038/nature05317. PMID 17151666.

{{cite journal}}: More than one of|first1=and|first=specified (help); More than one of|last1=and|last=specified (help); Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - Choi, Onelack (May 2005). "The Impacts of Socioeconomic Development and Climate Change on Severe Weather Catastrophe Losses: Mid-Atlantic Region (MAR) and the U.S." Climate Change. 58 (1–2): 149–170. doi:10.1023/A:1023459216609.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - Dyurgerov, Mark B. (2005). Glaciers and the Changing Earth System: a 2004 Snapshot (PDF). Institute of Arctic and Alpine Research Occasional Paper #58. ISSN 0069-6145.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - Emanuel, Kerry A. (2005-08-04). "Increasing destructiveness of tropical cyclones over the past 30 years" (PDF). Nature. 436 (7051): 686–688. doi:10.1038/nature03906. PMID 16056221.

{{cite journal}}: More than one of|first1=and|first=specified (help); More than one of|last1=and|last=specified (help) - Hansen, James (2005-06-03). "Earth's Energy Imbalance: Confirmation and Implications" (PDF). Science. 308 (5727): 1431–1435. doi:10.1126/science.1110252. PMID 15860591.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - Hinrichs, Kai-Uwe (2003-02-21). "Molecular Fossil Record of Elevated Methane Levels in Late Pleistocene Coastal Waters". Science. 299 (5610): 1214–1217. doi:10.1126/science.1079601. PMID 12595688.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - Hirsch, Tim (2006-01-11). "Plants revealed as methane source". BBC.

- Hoyt, Douglas V. (1993–11). "A discussion of plausible solar irradiance variations, 1700–1992". Journal of Geophysical Research. 98 (A11): 18, 895–18, 906. doi:10.1029/93JA01944.

{{cite journal}}: Check date values in:|year=(help); Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - "Climate Change: Adapting to the inevitable" (PDF). Institution of Mechanical Engineers. Retrieved 2009-03-07.

- Karnaukhov, A. V. (2001). "Role of the Biosphere in the Formation of the Earth's Climate: The Greenhouse Catastrophe" (PDF). Biophysics. 46 (6).

- Kenneth, James P. (2003-02-14). Methane Hydrates in Quaternary Climate Change: The Clathrate Gun Hypothesis. American Geophysical Union.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - Keppler, Frank (2006-01-18). "Global Warming – The Blame Is not with the Plants". Max Planck Society.

{{cite news}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - Lean, Judith L. (2002–12). "The effect of increasing solar activity on the Sun's total and open magnetic flux during multiple cycles: Implications for solar forcing of climate" (abstract). Geophysical Research Letters. 29 (24): 2224. doi:10.1029/2002GL015880.

{{cite journal}}: Check date values in:|date=(help); Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - Lerner, K. Lee (2006-07-26). Environmental issues: essential primary sources. Thomson Gale. ISBN 1414406258.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - Muscheler, Raimund, R; Joos, F; Müller, SA; Snowball, I (2005-07-28). "Climate: How unusual is today's solar activity?" (PDF). Nature. 436 (7012): 1084–1087. doi:10.1038/nature04045. PMID 16049429.

{{cite journal}}: More than one of|last1=and|last=specified (help); Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - Oerlemans, J. (2005-04-29). "Extracting a Climate Signal from 169 Glacier Records" (PDF). Science. 308 (5722): 675–677. doi:10.1126/science.1107046. PMID 15746388.

- Purse, Bethan V.; Mellor, PS; Rogers, DJ; Samuel, AR; Mertens, PP; Baylis, M (February 2005). "Climate change and the recent emergence of bluetongue in Europe" (abstract). Nature Reviews Microbiology. 3 (2): 171–181. doi:10.1038/nrmicro1090. PMID 15685226.

{{cite journal}}: More than one of|first1=and|first=specified (help); More than one of|last1=and|last=specified (help); Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - Revkin, Andrew C (2005-11-05). "Rise in Gases Unmatched by a History in Ancient Ice". The New York Times.

- Ruddiman, William F. (2005-12-15). Earth's Climate Past and Future. New York: Princeton University Press. ISBN 0-7167-3741-8.

- Ruddiman, William F. (2005-08-01). Plows, Plagues, and Petroleum: How Humans Took Control of Climate. New Jersey: Princeton University Press. ISBN 0-691-12164-8.

- Solanki, Sami K.; Usoskin, IG; Kromer, B; Schüssler, M; Beer, J (2004-10-23). "Unusual activity of the Sun during recent decades compared to the previous 11,000 years" (PDF). Nature. 431 (7012): 1084–1087. doi:10.1038/nature02995. PMID 15510145.

{{cite journal}}: More than one of|first1=and|first=specified (help); More than one of|last1=and|last=specified (help); Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - Solanki, Sami K. (2005-07-28). "Climate: How unusual is today's solar activity? (Reply)" (PDF). Nature. 436: E4–E5. doi:10.1038/nature04046.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - Sowers, Todd (2006-02-10). "Late Quaternary Atmospheric CH4 Isotope Record Suggests Marine Clathrates Are Stable". Science. 311 (5762): 838–840. doi:10.1126/science.1121235. PMID 16469923.

- Svensmark, Henrik (2007-02-08). "Experimental evidence for the role of ions in particle nucleation under atmospheric conditions". Proceedings of the Royal Society A. 463 (2078). FirstCite Early Online Publishing: 385–396. doi:10.1098/rspa.2006.1773.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help)(online version requires registration) - Walter, K. M.; Zimov, SA; Chanton, JP; Verbyla, D; Chapin Fs, 3rd (2006-09-07). "Methane bubbling from Siberian thaw lakes as a positive feedback to climate warming". Nature. 443 (7107): 71–75. doi:10.1038/nature05040. PMID 16957728.

{{cite journal}}: More than one of|first1=and|first=specified (help); More than one of|last1=and|last=specified (help); Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help)CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) - Wang, Y.-M. (2005-05-20). "Modeling the sun's magnetic field and irradiance since 1713" (PDF). Astrophysical Journal. 625: 522–538. doi:10.1086/429689.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - Royal Society (2005). "Joint science academies' statement: Global response to climate change". Retrieved 19 April 2009.

External links

- Research

- Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change — collection of IPCC reports

- Climate Change at the National Academies — repository for reports

- Nature Reports Climate Change — free-access web resource

- Met Office: Climate change — UK National Weather Service

- Global Science and Technology Sources on the Internet — extensive commented list of internet resources

- Educational Global Climate Modelling (EdGCM) — research-quality climate change simulator

- DISCOVER — satellite-based ocean and climate data since 1979 from NASA

- Global Warming Art — collection of figures and images

- Educational

- What Is Global Warming? — by National Geographic

- Global Warming Frequently Asked Questions — from NOAA

- Understanding Climate Change – Frequently Asked Questions — from UCAR

- Global Climate Change: NASA's Eyes on the Earth — from NASA's JPL and Caltech

- OurWorld 2.0 — from the United Nations University

- Pew Center on Global Climate Change — business and politics

- Best Effort Global Warming Trajectories – Wolfram Demonstrations Project — by Harvey Lam

- Koshland Science Museum – Global Warming Facts and Our Future — graphical introduction from National Academy of Sciences

- The Discovery of Global Warming – A History — by Spencer R. Weart from The American Institute of Physics

- Climate Change: Coral Reefs on the Edge — A video presentation by Prof. Ove Hoegh-Guldberg, University of Auckland

- Climate Change Indicators in the United States Report by United States Environmental Protection Agency, 80 pp.

- Global Warming

Template:Link FA Template:Link FA Template:Link FA Template:Link FA Template:Link FA Template:Link FA Template:Link FA Template:Link GA Template:Link GA Template:Link GA Template:Link GA