Albanians

| File:Albanians.png | |

| Total population | |

|---|---|

| approx. 7.8-7.9 Million | |

| Regions with significant populations | |

| Balkans: | 6 Million |

| 1,587,000[1] | |

| 500,000 1[2] | |

| 506,083[3] | |

| 274,390 - 600,000[4][5] | |

| 61,647[6] | |

| 33,600[7] | |

| 15,082 | |

| 10,000[8] | |

| 6,186[9] | |

| Rest of Europe: | 1,426,788+ |

| 700,000[10][11] | |

| 320,000 2 | |

| 200,000[12][13] | |

| 8,500[14] | |

| 60,000 | |

| 30,000[15] | |

| 10,000 | |

| 8,000[16] | |

| 2,788[17] | |

| Northern America: | 217,553+ |

| 201,118[18] | |

| 16,435[19] | |

| Languages | |

| Albanian (Gheg, Tosk, Arvanitika, Arbëresh, Cham) | |

| Religion | |

| Albanians are predominantly Muslim. In Albania there is a significant Christian minority with some professing non-religious . | |

1 Albanians are not recognized as a minority in Turkey. However approximately 500,000 people are reported to profess an Albanian identity. A more accurate number is hard to obtain, as most of Albanians living in Turkey do not speak Albanian, and some of them have only partial Albanian ancestry.

| |

| Part of a series on |

| Albanians |

|---|

|

|

|

Albanians (Template:Lang-sq) are a nation and ethnic group from southeast Europe who live in Albania, Kosovo and neighboring countries. They speak the Albanian language. Less than half of all Albanians live in Albania, with other large groups residing in Kosovo[a], Turkey, the Republic of Macedonia, Italy, Montenegro, Serbia, and Greece. The Albanian diaspora also exists in a number of other countries.

Ethnonym

While the exonym Albania for the general region inhabited by the Albanians does hark back to Classical Antiquity, and possibly to an Illyrian tribe, the name was lost within the Albanian language, the Albanian endonym being shqiptar, from the term for the Albanian language, shqip, a derivation of the verb shqiptoj "to speak clearly". This theory pertains to Hahn and it holds that perhaps the word is ultimately a loan from Latin excipio.[21] Thus, the Albanian endonym, like Slav and others, is in origin a term for "those who speak [intelligibly, the same language]". However another plausible theory has been advanced by Maximilian Lambertz to explain the endonym as derived from the Albanian noun shqype or shqiponjë (eagle), which, according to Albanian folk etymology, denoted a bird totem dating from the times of Skanderbeg, as displayed on the Albanian flag.[22]

In the 2nd century AD, Ptolemy, the geographer and astronomer from Alexandria, drafted a map that shows the city of Albanopolis (Greek,"Ἀλβανόπολις")[23] (located Northeast of Durrës). Ptolemy also mentions the Illyrian tribe named Albanoi, who lived around this city.

In History written in 1079–1080, the Byzantine historian Michael Attaliates referred to the Albanoi as having taken part in a revolt against Constantinople in 1043 and to the Arbanitai as subjects of the duke of Dyrrachium. It is disputed, however, whether that refers to Albanians in an ethnic sense.[24] The first reference to a lingua albanesca dates to the later 13th century (around 1285).[25]

The Albanians are and have been referred to by other terms as well. Some of them are:

- Arbër, Arbën, Arbëreshë; the old native term denoting ancient and medieval Albanians and sharing the same root with the latter. At the time the country was called Arbër (Gheg: Arbën) and Arbëria (Gheg: Arbënia). This term is still used for the Albanians that migrated to Italy during the Middle Ages.

- Arnauts (ارناود); old term used mainly from Turks and by extension by European authors during the Ottoman Empire. A derivate of the Turkish Arvanid (اروانيد), which derives from the Greek Arvanites.

- Skipetars; the historical rendering of the ethnonym Shqiptar (or Shqyptar by French, Austrian and German authors) in use from the 18th century (but probably earlier) to the present, the literal translation of which is subject of the eagle. The term Šiptari is a derivation used by Yugoslavs which the Albanians consider derogatory, preferring Albanci instead.

History

Albanians in the Middle Ages

What is possibly the earliest written reference to the Albanians is that to be found in an old Bulgarian text compiled around the beginning of the eleventh century. It was discovered in a Serbian manuscript dated 1628 and was first published in 1934 by Radoslav Grujic. This fragment of a legend from the time of Tsar Samuel endeavours, in a catechismal 'question and answer' form, to explain the origins of peoples and languages. It divides the world into seventy-two languages and three religious categories: Orthodox, half-believers (i.e. non-Orthodox Christians) and non-believers. The Albanians find their place among the nations of half-believers. If we accept the dating of Grujic, which is based primarily upon the contents of the text as a whole, this would be the earliest written document referring to the Albanians as a people or language group.[26]

It can be seen that there are various languages on earth. Of them, there are five Orthodox languages: Bulgarian, Greek, Syrian, Iberian (Georgian) and Russian. Three of these have Orthodox alphabets: Greek, Bulgarian and Iberian. There are twelve languages of half-believers: Alamanians, Franks, Magyars (Hungarians), Indians, Jacobites, Armenians, Saxons, Lechs (Poles), Arbanasi (Albanians), Croatians, Hizi, Germans.

The Albanians appear in the historical record in Byzantine sources of the late 11th century. At this point, they are already fully Christianized. Very little evidence of pre-Christian Albanian culture survives, and Albanian mythology and folklore, as it presents itself, is notoriously syncretized from various sources, showing in particular Greek influence.[27][need quotation to verify]

Regarding the classification of the Albanian language, it forms a separate branch of Indo-European, belonging to the Satem[28] group, and its late attestation, the first records dating to the 15th century, makes it difficult for historical linguistics to make confident statements on its genesis.[citation needed]

Other Latin provinces in Southeastern Europe (3rd century AD - 7th century AD)

The Balkans' prime function was to provide a bridge between the two halves of Empire; and many resources were devoted to maintaining the roads, and the towns and way-stations along them.[29][citation needed] Around 296 Emperor Diocletian secured the Danube frontier by building new fortresses.[30][citation needed] In the 4th century, the Danubian Plain north of the Haemus Mountains was still dotted with Roman towns and villas.[29]

However, the late 4th and early 5th century layers of the recently excavated Nicopolis ad Istrum are striking for the number of rich houses that suddenly appeared inside the city walls; it looks as though, since their country villas were now too vulnerable, the rich were running their estates from safe inside the city walls.[29] After the middle of the 5th century, medium-sized estates completely disappeared (with just a few exceptions, mainly in the coastal areas).[31][citation needed]

By 500, most, if not all, major cities in the Balkans had contracted and regrouped around a fortified precinct, almost always dominated by a church building.[31] A relatively large number of small houses was built in the 6th century in every city of the region, often within the ruins of previously large buildings.[31]

When Justinian I sought to re-establish Roman Illyricum in the 6th century, the essential foundation of strategically placed cities in the valleys created in the 1st and 2nd centuries, linked by policed roads and bridges, no longer existed.[32] During his reign, relatively small forts were built along the Danube and in the immediate hinterland.[31] Many forts on the mountain passes across the Stara Planina were comparatively larger.[31] Inside the walls, houses were built; and no other buildings exist besides churches.[31]

After 620, occupation ceased on most urban or military sites in the central Balkans, whose existence may have continued in one form or another into the early 7th century.[31] In several cases, there are clear signs of destruction by fire at some point after 600 AD.[31]

The key evidence for the population of the period between the 7th and 8th centuries is the Komani-Kruja group of cemeteries whose distribution is centered on Dyrrhachium (Durrës, Albania), and the general character of the remains suggests communities that were town-based and Christians.[32][citation needed]

There can surely be no doubt that the Komani-Kruja cemeteries indicate the survival of a non-Slav population between the sixth and ninth centuries, and their most likely identification seems to be with a Romanized population of Illyrian origin driven out by Slav settlements further north, the Romanoi mentioned by Constantine Porphyrogenitus.

Wilkes, John, 1995 (p. 278)

Albanians under the Ottoman Empire

The Ottoman supremacy in the Balkan region began in 1385 with the Battle of Savra but was briefly interrupted in the 15th century, when Gjergj Kastrioti, an Albanian warrior known as Skanderbeg, allied with some Albanian chiefs, formed the League of Lezhe and fought-off Turkish rule from 1443–1478 (although Kastrioti died in 1468). Kastrioti's strongholds included Kruja, Shkodra, Durres, Lezha, Petrela, Koxhaxhik and Berat.

Upon the Ottomans' return, a large number of Albanians fled to Italy, Greece and Egypt and maintained their Arbëresh identity.

Albanian national awakening

By the 1870s, the Sublime Porte's reforms aimed at checking the Ottoman Empire's disintegration had clearly failed. The image of the "Turkish yoke" had become fixed in the nationalist mythologies and psyches of the empire's Balkan peoples, and their march toward independence quickened. The Albanians, because of the higher degree of Islamic influence, their internal social divisions, and the fear that they would lose their Albanian-populated lands to the emerging Balkan states—Serbia, Montenegro, Bulgaria, and Greece—were the last of the Balkan peoples to desire division from the Ottoman Empire.[33]

Distribution

Balkans

Approximately 6.5 million Albanians are to be found within the Balkan peninsula[citation needed] with only about half this number residing in Albania and the other divided between Kosovo, Montenegro, the Republic of Macedonia, Greece and to a much smaller extent Bosnia, Bulgaria, Croatia, Romania, Serbia and Slovenia.

Albania

Albania has an estimated 3.2 million inhabitants,[34] of which Albanians amounting to 98.6% of the country's total population, making Albania one of the ethnically most homogenous states of Europe[citation needed].

Former Yugoslavia

An estimated 2.5 million Albanians live in the territory of Former Yugoslavia, the greater part (close to two million) in Kosovo[a].

Rights to use the Albanian language in education and government were given and guaranteed by the 1974 Constitution of SFRY and were widely utilized in Macedonia and in Montenegro before the Dissolution of Yugoslavia.[35]

Greece

Due to different waves of migration, Albanians and groups of Albanian descent are generally divided into three distinct groups.

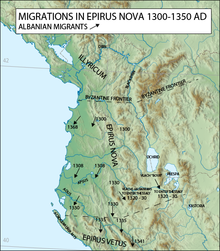

The first group is that of Arvanites and Albanian-speakers of Western Thrace, who retain a distinct ethnic identity, but self-identify nationally as Greeks. The Arvanites are descended from Tosk Albanians that migrated to Greece during the Middle Ages. They are Greek Orthodox Christians, and though they traditionally speak a dialect of Tosk Albanian known as Arvanitika, they have fully assimilated into the Greek nation and do not identify with the modern Albanian nation. They reportedly resent the designation "Albanians".[36] Arvanitika is in a state of attrition due to language shift towards Greek and large-scale internal migration to the cities and subsequent intermingling of the population during the 20th century.

The second group is that of the Cham Albanians and their descendants, in Epirus, in northwestern Greece. Muslim Chams were expelled from Epirus during World War II, by an anti-communist resistance group, as a result of their participation in a communist resistance group and the collaboration with the Axis occupation.

Alongside these two indigenous groups, about 10 percent of the population of Albania entered Greece after the fall of Communism, forming the third community of Albanian origin in Greece, the largest single expatriate group in the country today and the country's largest population group after the ethnic Greek majority. Their numbers are thought to range between 200,000 and 500,000.[citation needed]

Diaspora

This section needs additional citations for verification. (November 2009) |

The largest Albanian diasporic communities outside of the Balkans are found in Turkey (about 1.3 million, 13% of Albanians, 1.7% of host population), Italy (260,000), the United States (201,118; 0.09% of the total US population), Switzerland (320,000; about 2.5% of the total Swiss population), and Germany (over 300,000).

Europe

Approximately 3 million are dispersed throughout the rest of Europe, most of these in the United Kingdom, Italy, Germany, Switzerland, Sweden, Austria and France.

Italy has a historical Albanian minority known as the Arbëreshë which are scattered across Southern Italy, but the majority of Italo-Albanians have arrived since 1991 to surpass that of the older populations of Arbëreshë.

Turkey

According to a 2008 report prepared for the National Security Council of Turkey by academics of three Turkish universities in eastern Anatolia, there were approximately 1,300,000 people of Albanian descent living in Turkey.[37] A part of these people have assimilated to the culture of Turkey, and consider themselves more Turkish than Albanian. Nonetheless, more than 500,000 families of Albanian descents still recognize their ancestry like their languages, culture and traditions.

Americas

According to data from the 2008 Census of the United States Government, there are 201,118 Americans of full or partial Albanian descent.[38]

Asia and Oceania

In Australia and New Zealand 22,000 in total. Albanians are also known to reside in China, India, Iran, Japan, Korea, Malaysia, Pakistan and Singapore, but the numbers are generally small. 200,000 in all these countries. Albanians have been present in Arab countries such as Iraq, Jordan, Lebanon and Syria for about 5 centuries as a legacy of Ottoman Turkish rule.

Africa

In Egypt there are 18,000 Albanians, mostly Tosk speakers. Many are descendants of the soldiers of Mehmet Ali. A large part of the former nobility of Egypt was Albanian in origin. A small community also resides in South Africa.

Language

The Albanian language forms a separate branch of Indo-European languages family tree. A traditional view links the origin of Albanian with Illyrian, though this theory is broadly contested and challenged.[39]

Unattested prior to the second half of the 15th century, the Albanian language is one of the youngest languages of Europe in terms of first written account.

Albanian in a revised form of the Tosk dialect is the official language of Albania and Kosovo[a]; and is official in the municipalities where there are more than 20% ethnic Albanian inhabitants in the Republic of Macedonia. It is also an official language of Montenegro where it is spoken in the municipalities with ethnic Albanian populations.

Religion

The Albanians first appear in the historical record in Byzantine sources of the late 11th century.[40] At this point, they were already fully Christianized. Christianity was later overtaken by Islam, which kept the scepter of the major religion during the period of Ottoman Turkish rule from the 15th century until year 1912. Eastern Orthodox Christianity and Roman Catholicism continued to be practiced with less frequency.

During the 20th century the monarchy and later the totalitarian state followed a systematic secularization of the nation and the national culture. This policy was chiefly applied within the borders of the current Albanian state. It produced a secular majority in the population. All forms of Christianity, Islam and other religious practices were prohibited except for old non-institutional Pagan practices in the rural areas, which were seen as identifying with the national culture. The current Albanian state has revived some pagan festivals, such as the lunar Spring festival (Template:Lang-sq) held yearly on March 14 in the city of Elbasan. It is a national holiday.

A recent Pew Research Center demographic study put the percentage of Muslims in Albania at 79.9%.[41] Most of the Muslims in Albania are Sunni Muslims and Bektashi Shi'a Muslims[42][43] There are also Orthodox Christians, predominantly in Southern Albania, bordering Greece, and Roman Catholics is the main religion among those Albanians living predominantly in northern Albania, bordering the Republic of Montenegro. After 1992 an influx of foreign missionaries has brought more religious diversity with groups such as Jehovah's Witnesses, Mormons, Hindus, Bahá'í, a variety of Christian denominations and others. This rich blend of religions has however rarely caused religious strife. People of different religions freely intermarry. For part of its history, Albania has also had a Jewish community. Some of the members of the Jewish community were saved by a group of Albanians during the Nazi occupation.[44] Many left for Israel circa 1990-1992 after borders were open due to fall of communist regime in Albania.

Culture

Albanian music displays a variety of influences. Albanian folk music traditions differ by region, with major stylistic differences between the traditional music of the Ghegs in the north and Tosks in the south. Modern popular music has developed around the centers of Korca, Shkodër and Tirana. Since the 1920s, some composers such as Fan S. Noli have also produced works of Albanian classical music.

Notable Albanians

Gallery

-

Albanians in 1898.

-

Albanians in 1911.

-

Traditional presence of non Albanian communities in Albania.

-

Albanians outside Albania.

-

Albanians in Europe.

See also

- Albanoi

- Demographics of Albania

- Cham Albanians

- Arvanites

- Albanian diaspora

- Mandritsa

- Arbëreshë

- Albanian-American

- List of Albanians

- List of Albanian-Americans

Notes

Footnotes

| a. | ^ Template:Kosovo-note |

Citations

- ^ See [1] Template:Sh icon UN estimate, Kosovo’s population estimates range from 1.9 to 2.4 million. The last two population census conducted in 1981 and 1991 estimated Kosovo’s population at 1.6 and 1.9 million respectively, but the 1991 census probably under-counted Albanians. The latest estimate in 2001 by OSCE puts the number at 2.4 Million. The World Factbook gives an estimate of 1,804,838 persons living in Kosovo for the year 2009, 88% of them are Albanians. (see "Kosovo". The World Factbook (2024 ed.). Central Intelligence Agency.).

- ^ "Türkiye'deki Kürtlerin sayısı!" (in Turkish). 6 June 2008. Retrieved 17 August 2010.

- ^ "2002 Macedonian Census" (PDF). Retrieved 2010-09-22.

- ^ Migration and Migration Policy in Greece. Critical Review and Policy Recommendations. Anna Triandafyllidou. Hellenic Foundation for European and Foreign Policy (ELIAMEP). Data taken from Greek ministry of Interiors. p. 5 "the total number of Albanian citizens residing in Greece, including 185,000 co-ethnics holding special identity cards"

- ^ Gialis, Gialis. "Spatial demography of the Balkans: trends and challenges" (PDF). IVth International Conference of Balkans Demography. p. 4. Retrieved 4 November 2010., Kees, Groenendijk. "The status of quasi-citizenship in EU member states: Why some states have "almost-citizens"" (PDF). University of Edinburgh. pp. 415–416. Retrieved 4 November 2010.

- ^ Template:Sr icon Template:PDFlink, pp. 12-13

- ^ CIA Monenegro

- ^ "Date demografice" (in Romanian). Retrieved 18 August 2010.

- ^ "Population by ethnic affiliation in Slovenia". Stat.si. Retrieved 2010-09-22.

- ^ "Microsoft Word - pippo.doc" (PDF). Retrieved 2010-09-22.

- ^ "Ethnologue". Ethnologue. Retrieved 2010-09-22.

- ^ "Die Albaner in der Schweiz: Geschichtliches – Albaner in der Schweiz seit 1431" (PDF). Retrieved 2010-09-22.

- ^ "Im Namen aller Albaner eine Moschee?". Infowilplus.ch. 2007-05-25. Retrieved 2010-09-22.

- ^ "CBS - 8,5 duizend Kosovaren in Nederland - Webmagazine". Cbs.nl. Retrieved 2010-09-22.

- ^ Bennetto, Jason (2002-11-25). "Total Population of Albanians in the United Kingdom". London: Independent.co.uk. Retrieved 2010-09-22.

- ^ "National statistics of Denmark". Dst.dk. Retrieved 2010-09-22.

- ^ "Official Belgian Population Statistics" (in Template:Nl icon). Statbel.fgov.be. Retrieved 2010-09-22.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: unrecognized language (link) - ^ "US Census Bureau". Factfinder.census.gov. Retrieved 2010-09-22.

- ^ "Canadian Census of 2006". 2.statcan.gc.ca. 2008-06-10. Retrieved 2010-09-22.

- ^ The Albanian connection[dead link]

- ^ Robert Elsie, A dictionary of Albanian religion, mythology and folk culture, C. Hurst & Co. Publishers, 2001, ISBN 9781850655701, p. 79.

- ^ "ALBANCI". Enciklopedija Jugoslavije 2nd ed. Vol. Supplement. Zagreb: JLZ. 1984. p. 1.

- ^ Dictionary of Greek and Roman Geography (1854)William Smith, LLD, Ed.,Ptolemy is the earliest writer in whose works the name of the Albanians has been distinctly recognised. He mentions (3.13.23) a tribe called ALBANI (Ἀλβανοί) and a town ALBANOPOLIS (Ἀλβανόπολις), in the region lying to the E. of the Ionian sea; and from the names of places with which Albanopolis is connected, it appears clearly to have been in the S. part of the Illyrian territory, and in modern Albania. There are no means of forming a conjecture how the name of this obscure tribe came to be extended to so considerable a nation.

- ^ Pritsak, Omeljan (1991). "Albanians". Oxford Dictionary of Byzantium. Vol. 1. New York/Oxford: Oxford University Press. pp. 52–53.

- ^ "Robert Elsie, ''The earliest reference to the existence of the Albanian Language''". Scribd.com. 2007-05-28. Retrieved 2010-09-22.

- ^ Extract from: Grujic, Radoslav: Legenda iz vremena Cara Samuila o poreklu naroda. in: Glasnik skopskog naucnog drustva, Skopje, 13 (1934), p. 198 200. Translated from the Old Church Slavonic by Robert Elsie. First published in R. Elsie: Early Albania, a Reader of Historical Texts, 11th - 17th Centuries, Wiesbaden 2003, p. 3. Albanian History

- ^ Mircea Eliade, Charles J. Adams, The Encyclopedia of religion, Macmillan, 1987, ISBN 9780029097007, p. 179.

- ^ Encyclopaedia Britannica

- ^ a b c Heather. [Title needed]. [Publisher needed]. [Dated needed].

- ^ Treadgold. [Title needed]. [Publisher needed]. [Dated needed].

- ^ a b c d e f g h Curta. [Title needed]. [Publisher needed]. 2006.

- ^ a b Wilkes, John. [Title needed]. [Publisher needed]. p. [Page needed]. 1995.

- ^ Raymond Zickel and Walter R. Iwaskiw, editors. date= 1994. "National Awakening and the Birth of Albania, mut.us/albania/index.htm".

{{cite web}}:|access-date=requires|url=(help);|author=has generic name (help); Missing or empty|url=(help); Missing pipe in:|author=(help)CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) - ^ "Population as of 1 January 2010 (Popullsia më 1 Janar 2010)". Republic of Albania Institute of Statistics. Retrieved 2010-09-07.

- ^ Civil resistance in Kosovo By Howard Clark, pg. 12

- ^ GHM (1995).

- ^ Milliyet, Türkiyedeki Kürtlerin Sayısı. 2008-06-06.

- ^ "TOTAL ANCESTRY CATEGORIES TALLIED FOR PEOPLE WITH ONE OR MORE ANCESTRY CATEGORIES REPORTED". U.S. Census Bureau. Retrieved 2010-08-17.

- ^ Hans Henrich Hock, Brian D. Joseph: Language history, language change, and language relationship, pp. 54

- ^ Comnena, Anna. The Alexiad, Book IV.

- ^ Miller, Tracy, ed. (2009), Mapping the Global Muslim Population: A Report on the Size and Distribution of the World’s Muslim Population (PDF), Pew Research Center, retrieved 2009-10-08

{{citation}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) [dead link] - ^ Albania. The World Factbook.

- ^ Muslims in Europe: Country guide: Albania. BBC.

- ^ Rescue in Albania: One Hundred Percent of Jews in Albania Rescued from Holocaust". "The Jews of Albania". California: Brunswick Press, 1997. Retrieved on 29 January 2007.

Further reading

External links

- Albanians in Turkey

- Albanian Canadian League Information Service (ACLIS)

- Albanians in the Balkans U.S. Institute of Peace Report, November 2001

- Books about Albania and the Albanian people (scribd.com) Reference of books (and some journal articles) about Albania and the Albanian people; their history, language, origin, culture, literature, etc. Public domain books, fully accessible online.

- Albanian people

- Ethnic groups in Europe

- Ethnic groups in Albania

- Ethnic groups in Kosovo

- Ethnic groups in the Republic of Macedonia

- Ethnic groups in Montenegro

- Ethnic groups in Serbia

- Ethnic groups in Russia

- Ethnic groups in Bosnia and Herzegovina

- Ethnic groups in Greece

- Ethnic groups in Italy

- Indo-European peoples

- Muslim communities

- Ethnic groups in the Balkans