Donkey Kong (1981 video game)

| Donkey Kong | |

|---|---|

| Donkey Kong Title Screen | |

| Developer(s) | Nintendo |

| Publisher(s) | Nintendo |

| Designer(s) | Shigeru Miyamoto |

| Platform(s) | |

| Release | 1981 |

| Genre(s) | Retro/Platform |

| Mode(s) | Up to two players, alternating turns |

| Arcade system | Main CPU: Zilog Z80 (@ 3.072 MHz) Sound CPU: I8035 (@ 400 kHz) Sound Chips: DAC (@ 400 kHz), Samples (@ 400 kHz) |

Donkey Kong (Japanese: ドンキーコング) is an arcade game created by Nintendo and released in 1981. The game is an early example of the platform genre; gameplay focuses on maneuvering the main character across a series of platforms while dodging obstacles. The storyline is thin but well developed for its time. In it, Mario (originally called Jumpman) must rescue a damsel in distress from a giant ape named Donkey Kong. The hero and ape would go on to be two of Nintendo's more popular characters.

The game was the latest of Nintendo's efforts to break into the North American market. Nintendo president Hiroshi Yamauchi assigned the project to a first-time game designer named Shigeru Miyamoto. Drawing from a wide range of inspirations, including Popeye and King Kong, Miyamoto developed the scenario and designed the game alongside Nintendo's chief engineer, Gunpei Yokoi. The two men broke new ground by using graphics as a means of characterization, including cut scenes to advance the game's plot, and integrating multiple stages into the gameplay.

Despite initial misgivings on the part of Nintendo's American staff, Donkey Kong proved a tremendous success in both North America and Japan. Nintendo licensed the game to Coleco, who developed home console versions for numerous platforms; other companies simply cloned Nintendo's hit and avoided royalties altogether. Miyamoto's characters appeared on cereal boxes, television cartoons, and dozens of other places. A court suit brought on by Universal City Studios alleging that Donkey Kong violated their trademark of King Kong ultimately failed. The success of Donkey Kong and Nintendo's win in the courtroom helped position the company to dominate the video game market in the 1980s and early 1990s.

Story and characters

The eponymous Donkey Kong plays the game's de facto villain. He is the pet of a carpenter named Jumpman (an amalgamation of Walkman and Pac-Man, later renamed Mario).[1] The carpenter mistreats the ape, so Donkey Kong escapes and kidnaps Jumpman's girlfriend, originally known as the Lady, but later renamed Pauline. The player must take the role of Jumpman and rescue the girl. This was the first occurrence of the inherently heterosexual damsel-in-distress scenario that would provide the template for countless video games to come.[2]

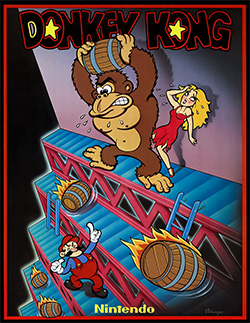

The game uses graphics and animation as vehicles of characterization. Donkey Kong smirks upon Jumpman's demise. Pauline is instantly recognized as female from her pink dress and long hair,[3] and "HELP!" appears frequently beside her. Jumpman, depicted in red overalls and cap, is an everyman character, a type common in Japan. Graphical limitations forced his design: Drawing a mouth was too difficult, so the character got a mustache;[4] the programmers could not animate hair, so he got a cap; and to make his arm movements visible, he needed white gloves and colored overalls.[5] The artwork used for the cabinets and promotional materials make these cartoon-like character designs even more explicit. Pauline, for example, appears as a disheveled Fay Wray in a torn dress and stiletto heels.

Donkey Kong is the first example of a complete narrative told in video game form, and it employs cut scenes to advance its plot. The game opens with the gorilla climbing a pair of ladders to the top of a construction site. He sets Pauline down and stamps his feet, causing the steel beams to change shape. He then moves to his final perch and sneers. This brief animation sets the scene and adds background to the gameplay, a first for video games. Upon reaching the end of the stage, another cut scene begins. A heart appears between Jumpman and Pauline, but Donkey Kong grabs the woman and climbs higher, causing the heart to break. The narrative concludes when Jumpman reaches the end of the final stage. He and Pauline are reunited, and the game's end titles play.[6]

Gameplay

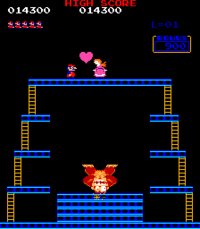

Donkey Kong is an early example of the platform genre (it is sometimes said to be the first platform game, although it was preceded by Space Panic and Apple Panic).[7] The game is divided into four different one-screen stages. Each represents 25 meters of the structure Donkey Kong has climbed, one being 25 meters higher than the previous. The final screen occurs at 100m.

Winning the game requires patience and the ability to accurately time Jumpman's ascent.[2] In addition to presenting the goal of saving the lady, the game also gives the player a score. Points are awarded for finishing screens; leaping over obstacles; destroying objects with a hammer power-up; collecting items such as hats, umbrellas and purses (presumably belonging to Pauline); and completing other tasks. The player receives three lives with a bonus awarded for every 7,000 points. The screens are as follows:

- Screen 1 (25m) — Jumpman/Mario must scale a seven-story construction site made of crooked girders and ladders while jumping over or hammering barrels and oil barrels tossed by Donkey Kong. The hero must also avoid flaming balls, which generate when an oil barrel collides with an oil drum.

- Screen 2 (50m) — Jumpman/Mario must climb a five-story structure of conveyor belts, each of which transports pans of cement. The fireballs also make another appearance. This screen does not appear in the Nintendo Entertainment System version of the game and some other console versions. This stage is sometimes referred to as the pie factory due to the resemblance of the cement pans to pies.

- Screen 3 (75m) — Jumpman/Mario rides up and down elevators while avoiding fireballs and bouncing objects, presumably spring-weights. The bouncing weights (the hero's greatest danger in this screen) emerge on the top level and drop near the rightmost elevator.

- Screen 4 (100m) — Jumpman/Mario must remove eight rivets, which support Donkey Kong. The fireballs remain the main obstacle. Removing the final rivet causes Donkey Kong to fall and the hero to be reunited with Pauline. This is the final screen of each level. The victory music alternates between levels 1 and 2.

These screens combine to form levels, which become progressively harder. For example, Donkey Kong begins to hurl barrels more rapidly and sometimes diagonally, and fireballs get quicker. The 22nd level is unofficially known as the kill screen due to an error in the game's programming that starts the clock with far less time than is necessary to complete the stage. At four screens, Donkey Kong at its debut was the biggest video game ever produced. In fact, the only use of multiple levels to precede it was Gorf by Midway Games.

-

Screen 1

-

Screen 2

-

Screen 3

-

Screen 4

Development

By the late 1970s, Nintendo's efforts to crack the North American market had all failed, culminating with the flop Radarscope in 1979. In order to keep the company afloat, company president Hiroshi Yamauchi decided to convert unsold Radarscope games into something new. He approached a young industrial designer named Shigeru Miyamoto, who had been working for Nintendo since 1977, to see if Miyamoto thought that he could design an arcade game. Miyamoto said said that he could.[8] Yamauchi appointed Nintendo's head engineer, Gunpei Yokoi, to supervise the project.

At the time, Nintendo was pursuing a license to make a game based on the Popeye comic strip. When this fell through, Nintendo decided that it would take the opportunity to create new characters that could then be marketed and used in later games.[5] Miyamoto came up with many characters and plot concepts, but he eventually settled on a gorilla/carpenter/girlfriend love triangle that mirrored the rivalry between Bluto and Popeye for Olive Oyl.[1] Bluto became an ape, who in Miyamoto's words was "nothing too evil or repulsive". He would be the pet of the main character, "a funny, hang-loose kind of guy".[9] Miyamoto has also named "Beauty and the Beast" and the 1933 film King Kong as influences.[10] Although its origin as a comic strip license played a major part, Donkey Kong marked the first time that the storyline for a video game preceded the game's programming rather than simply being appended as an afterthought.[11]

Yamauchi wanted to primarily target the North American market, so he mandated that the game be given an English title. Miyamoto decided to name the game for the ape, whom he felt to be the strongest character.[1] The story of exactly how Miyamoto came up with the name Donkey Kong varies; one telling claims that he looked in a Japanese-English dictionary for something that would mean stubborn gorilla.[12] Another version claims that Donkey was meant to convey silly and that Kong was common Japanese slang for gorilla.[5] Another claim is that he worked with Nintendo's export manager to come up with the name, and that Donkey was meant to represent stupid and goofy.[13]

Miyamoto had high hopes for his new project. He lacked the technical background to program it himself, so he instead came up with concepts and ran them by the technicians to see if they were possible. He wanted to make the characters different sizes, move them in different manners, and make them react in various ways. Yokoi declared Miyamoto's original design too complex.[14] Another idea that Yokoi himself suggested was to use see-saws that the hero could use to catapult himself across the screen; this too proved too difficult to program. Miyamoto then came up with the idea to use sloped platforms, barrels, and ladders. When he specified that the game would have multiple stages, the four-man programming team complained that he was essentially asking them to make the game over and over.[15] Nevertheless, they followed Miyamoto's design, creating about 20k of code.[16] Meanwhile, Miyamoto composed the game's music on an electronic keyboard.

Hiroshi Yamauchi knew that Nintendo had a hit on its hands and called up Minoru Arakawa, head of Nintendo's operations in the U.S., to tell him.[17] Arakawa went to work securing a trademark patent, and Ron Judy and Al Stone, Nintendo's American distributors, brought him to a lawyer named Howard Lincoln.

The game was sent to Nintendo of America for testing. The sales manager hated it for being too different from the maze and shooter games common at the time,[18] and Judy and Lincoln expressed reservations over the strange title. Still, Arakawa swore that it would be big.[17] American staffers pleaded with Yamauchi to at least change the name, but he refused. Resigned, Arakawa and the American staff set about translating the storyline for the cabinet art and naming the other characters. They chose "Pauline" for the girl, after Don James's wife, Polly. "Mario" was named for Mario Segale, the landlord of Nintendo's Redmond, Washington, warehouse.[19] These character names were printed on the American cabinet art and used in promotional materials. Donkey Kong was ready for release.

Stone and Judy convinced the managers of two bars in Seattle, Washington, to set up Donkey Kong machines. The managers initially showed reluctance, but when they saw sales of $30 a day—or 120 plays—for a week straight, they requested more units.[20] In their Redmond headquarters, a skeleton crew composed of Arakawa, his wife Yoko, James, Judy, Phillips, and Stone set about gutting 2,000 surplus Radarscope machines and converting them with Donkey Kong mother boards and power supplies from Japan. The game officially went on sale in July 1981.

In his 1982 book Video Invaders, Steve Bloom describes Donkey Kong as "another bizarre cartoon game, courtesy of Japan."[21] To American and Canadian gamers, however, Donkey Kong was irresistible. The game's initial 2,000 units sold through, and more orders poured in. Arakawa began manufacturing the electronic components in Redmond because waiting for shipments from Japan was taking too long.[22] By October, Donkey Kong was selling 4,000 units a month, and by late June 1982, Nintendo had sold 60,000 Donkey Kong games over all and earned some $180 million.[23] Judy and Stone, who worked on straight commission, became millionaires.[22] Arakawa used Nintendo's profits to buy 27 acres of land in Redmond in July 1982.[24] The game made another $100 million in its second year of release.[25] It remained Nintendo's top seller even into Summer 1983.[26] Donkey Kong sold steadily in Japan, as well.[27]

Its success entrenched the game in American popular culture. In 1982, Buckner and Garcia and R. Cade and the Video Victims both recorded songs based on the game. Artists like DJ Jazzy Jeff and the Fresh Prince and Trace Adkins referenced the game in songs, as did The Simpsons in the episode "Homer and Ned's Hail Mary Pass". Sound effects from the Atari 2600 version often serve as generic video game sounds in films and television shows. The Killer List of Videogames ranks Donkey Kong the third most popular arcade game of all time and places it at #25 on the "Top 100 Videogames" list. Today, Donkey Kong is the fifth most popular arcade game among collectors.[28]

Licensing and ports

By late June 1982, Donkey Kong's success had prompted more than 50 parties in the U.S. and Japan to license the game's characters.[29] Mario and his simian nemesis appeared on cereal boxes, board games, pajamas, and manga. In 1983, the animation studio Ruby-Spears produced a Donkey Kong cartoon (as well as Donkey Kong Jr) for the Saturday Supercade program on CBS. In the show, mystery crime-solving plots in the mode of Scooby-Doo are framed around the premise of Mario chasing Donkey Kong, who has captured Pauline. The show lasted two seasons.

Makers of video game consoles were interested, as well. Taito offered a considerable sum to buy all rights to Donkey Kong, but Nintendo turned them down.[30] Rivals Coleco and Atari approached Nintendo in Japan and the United States respectively. In the end, Yamauchi granted Coleco exclusive home-version and tabletop rights to Donkey Kong because he felt that "It [was] the hungriest company".[31] In addition, Arakawa felt that as a more estabished company in the US, Coleco could better handle marketing. In return, Nintendo would receive an undisclosed lump sum plus $1.40 per game cartridge sold and $1 per tabletop unit. On 24 December 1981, Howard Lincoln drafted the contract. He included language that Coleco would be held liable for anything on the game cartridge, an unusual clause for a licensing agreement.[32] Arakawa signed the document the next day, and on 1 February 1982, Yamauchi persuaded the Coleco representative in Japan to sign without running the document by the company's lawyers.[33]

Coleco did not offer the game stand-alone; instead, they bundled it with their Colecovision. The units went on sale in July 1982. Coleco's version is very close to the arcade, moreso than ports of earlier games that had been done. Six months later, Coleco offered Atari 2600, Intellivision, and VCS versions, too. Coleco's sales doubled to $500 million and their earnings quadrupled to $40 million.[34]

Meanwhile, Atari got the rights to the floppy disk version of Donkey Kong and prepared the Atari 800 version of the game. When Coleco unveiled the Adam Computer, playing a port of Donkey Kong at the 1983 Summer Consumer Electronics Show in Chicago, Illinois, Atari protested. Yamauchi demanded that Arnold Greenberg, Coleco's president, shelve his Adam port. This version of the game was cartridge-based, and thus not a violation of Nintendo's license with Atari; still, Greenberg complied. Ray Kassar of Atari was fired the next month, and the home PC version of Donkey Kong fell through.[35]

Miyamoto created a greatly simplified version for the Game & Watch multiscreen, and in 1983, Donkey Kong was an early release for the Nintendo Entertainment System (NES) in Japan. This version remained in production until 1988. Other ports include the Apple II, Atari 7800, Commodore 64, Commodore VIC-20, PC, ZX Spectrum, Mini-Arcade, and TI-99/4A.

In 1994, Nintendo released the enhanced remake Donkey Kong on the Game Boy, the first game with enhanced Super Game Boy support. This port features many new stages, enhanced graphics and controls. A version of the game appears in the Nintendo 64 game Donkey Kong 64 and another in the GameCube game Animal Crossing (although that is the NES port, not the original arcade version). In 2004, Nintendo released the NES version for the Game Boy Advance Classic NES series and on the e-Reader.

Clones and sequels

Other companies bypassed Nintendo completely. In 1981, O. R. Rissman, president of Tiger Electronics, obtained a license to use the name King Kong from Universal City Studios. Under this title, Tiger created a handheld game with a scenario and gameplay based directly on Nintendo's creation.

Crazy Kong is another example, a clone manufactured by Falcon and licensed for some non-American markets. Nevertheless, Crazy Kong machines found their way into some American arcades during the early 1980s, often installed in cabinets marked as Congorilla. Nintendo was quick to take legal action against those distributing the game in the U.S.[36] Bootleg copies of Donkey Kong also appeared in both North America and France under the Crazy Kong or Donkey King names. In 1983, Sega created its own Donkey Kong clone called Congo Bongo. The game features an isometric perspective, but the gameplay is very similar.

Donkey Kong spawned two direct sequels: Donkey Kong Jr. and Donkey Kong 3. Mario Bros. is a spin-off featuring Mario. Rareware revived the Donkey Kong license in the 1990s for a series of platform games and spin-offs, beginning with Donkey Kong Country in 1994. Donkey Kong 64 (1999) is the latest in this series.

Universal City Studios, Inc. v. Nintendo Co., Ltd.

- Main article: Universal City Studios, Inc. v. Nintendo Co., Ltd.

Nintendo's success with Donkey Kong was not without obstacles. In April 1982, Sid Sheinberg, a seasoned lawyer and president of MCA and Universal City Studios, learned of the game's success and suspected it might be a trademark infringement of Universal's own King Kong.[23] On 27 April 1982, he met with Arnold Greenberg of Coleco and threatened to sue. Coleco agreed on 5 May to pay royalties to Universal of 3% of their Donkey Kong's net sale price, worth about $4.6 million.[37] Meanwhile, Steinberg revoked Tiger's license to make its King Kong game, but O. R. Rissman refused to acknowledge Universal's claim to the trademark.[38] For their part, Howard Lincoln and Nintendo refused to cave to Universal's threats. In preparation for the court battle ahead, Universal agreed to allow Tiger to continue producing its King Kong game as long as they distinguished it from Donkey Kong.

Universal officially sued Nintendo on 29 June 1982 and announced its license with Coleco. The company sent cease-and-decist letters to Nintendo's licensees, all of which agreed to pay royalties to Universal except Milton Bradley and Ralston Purina.[39]

Universal City Studios, Inc. v. Nintendo, Co., Ltd. was heard in the United States District Court for the Southern District of New York by Judge Robert W. Sweet. Over seven days, Universal's counsel, the New York firm Townley & Updike, argued that the names King Kong and Donkey Kong were easily confused and that the plot of the game was an infringement on that of the films.[40] Nintendo's counsel, John Kirby, countered that Universal had themselves argued in a previous case that King Kong's scenario and characters were in the public domain. Judge Sweet ruled in Nintendo's favor, awarding the company Universal's profits from Tiger's game ($56,689.41), damages, and attorney's fees.[41]

Universal appealed, trying to prove consumer confusion by presenting the results of a telephone survey and examples from print media where people had allegedly assumed a connection between the two Kongs.[42] On 4 October 1984, however, the court upheld the previous verdict.

Nintendo and its licensees filed counterclaims against Universal. On 20 May 1985, Judge Sweet awarded Nintendo $1.8 million for legal fees, lost revenues, and other expenses.[43] However, he denied Nintendo's claim of damages from those licensees who had paid royalties to both Nintendo and Universal.[44] This judgement was appealed by both parties, but the verdict was upheld on 15 July 1986.[45]

Nintendo thanked John Kirby with a $30,000 sailboat christined the Donkey Kong along with "exclusive worldwide rights to use the name for sailboats."[46] More importantly, the court battle was a rite of passage for the company, teaching Nintendo that they could compete with the giants of the entertainment industry.[47]

Notes

- ^ a b c Kohler 39.

- ^ a b De Maria 82.

- ^ Ray 19-20.

- ^ Kohler 37.

- ^ a b c De Maria 238.

- ^ Kohler 40-2.

- ^ Crawford 94.

- ^ Kent 157.

- ^ Both quotes from Sheff 47.

- ^ Kohler 36.

- ^ Kohler 38.

- ^ Kent 158.

- ^ Sheff 48-9.

- ^ Sheff 47-48.

- ^ Kohler 38-39.

- ^ Kent 530.

- ^ a b Kent 159.

- ^ Sheff 49.

- ^ Sheff 109.

- ^ Sellers 68.

- ^ Quoted in Kohler 5.

- ^ a b Kent 160.

- ^ a b Kent 211.

- ^ Sheff 113.

- ^ Sheff 111.

- ^ Kent 284.

- ^ Kohler 46.

- ^ McLemore.

- ^ Kent 215.

- ^ Sheff 110.

- ^ Quoted in Sheff 111.

- ^ Kent 208-9.

- ^ Sheff 112.

- ^ Kent 210.

- ^ Kent 283-5.

- ^ Second Court of Appeals, 1984, 119.

- ^ Sheff 121.

- ^ Kent 214.

- ^ Second Court of Appeals, 1986, 74-5.

- ^ Second Court of Appeals, 1986, 74.

- ^ Kent 217.

- ^ Second Court of Appeals, 1984, 118.

- ^ Kent 218.

- ^ Second Court of Appeals, 1986, 72.

- ^ Second Court of Appeals, 1986, 77-8.

- ^ Quoted in Sheff 126.

- ^ Sheff 127.

References

- Consalvo, Mia (2003). “Hot Dates and Fairy-tale Romances”. ‘’The Video Game Theory Reader’’. New York: Routledge.

- Crawford, Chirs (2003). Chris Crawford on Game Design. New Riders Publishing.

- De Maria, Rusel, and Wilson, Johnny L. (2004). High Score!: The Illustrated History of Electronic Games. 2nd ed. New York: McGraw-Hill/Osborne.

- Kent, Steven L. (2001). The Ultimate History of Video Games: The Story behind the Craze that Touched Our Lives and Changed the World. New York City: Three Rivers Press.

- Kohler, Kris (2005). Power-up: How Japanese Video Games Gave the World an Extra Life. Indianapolis, Indiana: BradyGAMES.

- McLemore, Greg, et al. (2005). "The Top Coin-operated Videogames of All Time". Accessed 15 February 2006.

- Miyamoto, Shigeru, designer (1981). Donkey Kong. Nintendo.

- Ray, Sheri Graner (2004). Gender Inclusive Gave Design: Expanding the Market. Hingham, Massachusetts: Charles Rivers Media, Inc.

- Schodt, Frederick L. (1996). Dreamland Japan: Writings on Modern Manga. Berkeley, California: Stone Bridge Press.

- Sellers, John (2001). Arcade Fever: The Fan's Guide to the Golden Age of Video Games. Philadelphia: Running Book Publishers.

- Sheff, David (1999). Game Over: Press Start to Continue: The Maturing of Mario. Wilton, Connecticut: GamePress.

- United States Court of Appeals, Second Circuit (4 October 1984). Universal City Studios, Inc. v. Nintendo Co., Ltd.

- United States Court of Appeals, Second Circuit (15 July 1986). Universal City Studios, Inc. v. Nintendo Co., Ltd.

External links

- Mario platform games

- Arcade games

- 1981 computer and video games

- 1981 arcade games

- Apple II games

- Atari 2600 games

- Atari 7800 games

- Atari 8-bit family games

- ColecoVision games

- Commodore 64 games

- Commodore VIC-20 games

- E-Reader games

- Game & Watch games

- Game Boy Advance games

- Intellivision games

- NES games

- TI-99/4A games

- ZX Spectrum games