Police brutality

Police brutality is the wanton use of excessive force, usually physical, but potentially in the form of verbal attacks and psychological intimidation, by a police officer.

Widespread police brutality exists in many countries, even those that prosecute it.[1] It is one of several forms of police misconduct, which include:[citation needed] false arrest; intimidation; racial profiling; political repression; surveillance abuse; sexual abuse; and police corruption. However, as aformentioned, it may involve physical force but never reaching death under police custody.[citation needed]

History

The word "brutality" has several meanings; the sense used here (savage cruelty) was first used in 1633.[2] The first known use of the term "police brutality" was in the New York Times in 1893,[3] describing a police officer's beating of a civilian.

The origin of modern policing based on the authority of the nation state is commonly traced back to developments in seventeenth and eighteenth century France, with modern police departments being established in most nations by the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. Cases of police brutality appear to have been frequent then, with "the routine bludgeoning of citizens by patrolmen armed with nightsticks or blackjacks."[4] Large-scale incidents of brutality were associated with labor strikes, such as the Great Railroad Strike of 1877, the Pullman Strike of 1894, the Lawrence textile strike of 1912, the Ludlow massacre of 1914, the Steel strike of 1919, and the Hanapepe massacre of 1924.

Portions of the population may perceive the police to be oppressors. In addition, there is a perception that victims of police brutality often belong to relatively powerless groups, such as minorities, the disabled, the young, and the poor.[5]

Hubert Locke writes,

When used in print or as the battle cry in a black power rally, police brutality can by implication cover a number of practices, from calling a citizen by his or her first name to a death by a policeman's bullet. What the average citizen thinks of when he hears the term, however, is something midway between these two occurrences, something more akin to what the police profession knows as "alley court"—the wanton vicious beating of a person in custody, usually while handcuffed, and usually taking place somewhere between the scene of the arrest and the station house.[6]

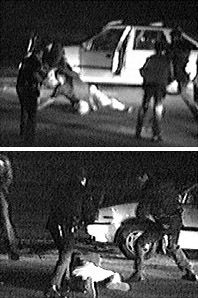

In 1992, Los Angeles police harshly beat African American Rodney King. The police officers involved were acquitted and is widely believed to have lead up to the Los Angeles riots of 1992, causing 53 deaths, 2,383 injuries, more than 7,000 fires, damage to 3,100 businesses, and nearly $1 billion in financial losses. After facing federal trial, the officers received 32 months prison sentence. The case was widely seen as a key factor in the reform of the Los Angeles police department.

International

Belgium

Brussels' police arrested 30 rioters on 26 September 45 rioters on 27 September and 53 rioters on 28 September during 2006 Brussels riots.[7] Police said some of those arrested were carrying material to make petrol bombs.[8] At least 242 crime files were opened by the police.

France

2007 civil unrest in Villiers-le-Bel unrest began when the minibike, on which the youths were riding, collided with a police vehicle.[9] The families of the youths allege that police rammed the motorcycle and left the two teenagers for dead.[10] The police deny this, saying that the motorcycle was stolen[11][12] and was an unregistered vehicle not valid for street use, travelling at high speed, and that the youths were not wearing any protective headgear - an account, according to French newspaper reports, confirmed by two eyewitnesses.[13] A police investigation indicated that the motorcycle was in third (top) gear and that the police car was not going over 40 km/h (25 mph).[13]

People's Republic of China

Politically motivated riots and protest have occurred historically in China, notably with the Tiananmen Square protests of 1989. Within the past decade, groups such as Falun Gong have protested party measures and been broken up by riot police. Chinese dissidents have been able to arrange effective mobilization through use of social media and informal communication like Twitter and its Chinese counterparts Weibo or microblogs.[14]

Foreign journalists from Switzerland have reported cases of police harassment. Media suppression has increased in the wake of the Jasmine Revolution in Tunisia. Plainclothes policemen are often deployed during demonstrations to suppress violence. Censorship is often maintained as a measure to maintain political stability in China. Web activists can be charged by the police for using false identities to surf the Internet. After arrests, homes of the arrested individual are often searched for incriminating evidence such as computers, hard drives, and flash drives.[15]

Russia

Russian protests have gained media attention with the reelection of Vladimir Putin in 2012. Attention has been given to incidence of violence via posting videos online. President Dmitry Medvedev has initiated reforms of the police force, in an attempt to minimize the violence by firing Moscow police chief and centralizing police powers. Police divisions in Russia are often based on loyalty systems that favor bureaucratic power amongst political elites. Phone tapping and business raids are common practice in the country, and often fail to give due process to citizens. Proper investigations of police officials still remains lacking by western standards.[16]

In 2012, Russia's top investigative agency investigated charges that four police officers had tortured detainees under custody. Human rights activists claim that Russian police use torture techniques to extract false confessions from detainees. Police regulations require quotas of officers for solved crimes, a practice that encourages false arrests to meet their numbers.[17]

Indonesia

Islamic extremists in Indonesia have been targeted by police as terrorists in the country. Police may either capture or kill dissidents. Cases of police corruption with hidden bank accounts and retaliation against journalists who attempt to uncover these cases have occurred such as in June 2012, when Indonesian magazine Tempo had journalist activists beaten by police. Separately, on August 31, 2010 police officers in Central Sulawesi province fired into a crowd of people protesting the death of a local man in police custody. Five people were killed and 34 injured. History of violence goes back to the military-backed Suharto regime (1967-1998), from which Suharto seized power during an anti-Communist purge.[18]

Criminal investigations into human rights violations by the police are rare, punishments light and Indonesia has no independent national body to deal effectively with public complaints. Amnesty International has called on Indonesia to review police tactics during arrests and public order policing, to ensure that they meet international standards.[19]

Canada

There have been a number of high profile cases of alleged police brutality including, 2010 G-20 Toronto summit protests,[20] the 2012 Quebec student protests[21] and the Robert Dziekański taser incident. The recent public incidents in which police judgments or actions have been called into question have raised fundamental concerns about police accountability and governance.[22]

Turkey

Turkey has a history of police brutality, including (particularly between 1977 and 2002) the use of torture. Police brutality featuring excessive use of tear gas (including targeting protestors with tear gas canisters), pepper spray and water cannon as well as physical violence against protestors has been seen, for example, in the suppression of Kurdish protests and May Day demonstrations. The 2013 protests in Turkey were in response to the brutal police suppression of an environmentalist sit-in protesting the removal of Taksim Gezi Park.

In 2012 a number of officials received prison sentences for their role in the death in custody of political activist Engin Çeber.

Sweden

On 19 May 2013, youth riots broke out in Husby, a suburb with a relatively high proportion of immigrant and Muslim residents, in northern Stockholm, Sweden.[23] The riots were reportedly a response to the shooting and killing by police of an elderly man, allegedly a Portuguese expat,[24][25][26] armed with a machete[9] or a jackknife, after breaking into his apartment, and then allegedly trying to cover up the incident.[27]

United Kingdom

On 3 December 2012, Belfast City Council voted to limit the days that the Union Flag (the flag of the United Kingdom) flies from Belfast City Hall.[28] Since 1906, the flag had been flown every day of the year. The vote means that it will now be flown no more than 18 days a year. The move to limit the number of days was backed by the council's Irish nationalists and the Alliance Party; it was opposed by the unionist councillors. As a response, loyalists and unionists have held street protests throughout Northern Ireland. The loyalist and unionist protesters see the change as an "attack on their cultural identity".[29] In December 2012 and early 2013 they held almost daily street protests throughout Northern Ireland. Most involved the protesters blocking roads while carrying Union Flags and banners. Some of these protests led to clashes between loyalists and the Police Service of Northern Ireland (PSNI), sparking riots. Attacks were made on Alliance Party offices and the homes of Alliance Party members, while Belfast City councillors were sent death threats. Unlike the Irish nationalist parties, Alliance has offices in loyalist areas.[29] According to police, some of the violence has been orchestrated by high-ranking members of the Ulster Volunteer Force (UVF) and Ulster Defence Association (UDA).[30] These are the two main loyalist paramilitary groups, who waged armed campaigns during The Troubles but declared ceasefires in 1994. The Belfast Telegraph claimed that some of the violence has been fuelled by youngsters engaging in "recreational rioting".[31] There was also a rise in sectarian attacks on Catholic churches by loyalist militants, which some have linked to the flag protests.[32][33][34] The cost of policing the protests has been estimated at £20 million (up to 7 March 2013).[35]

United States

Police brutality in the United States is the most widely discussed, since United States of America wants to export democracy and human rights. The first known use of the term "police brutality" was in the New York Times in 1893,[36] describing a police officer's beating of a civilian. Police brutality increased especially after September 11, 2001 attacks on the World Trade Center. The brutality by police was observed almost in all states of the country.

Causes

Police officers are legally permitted to use force, and their superiors — and the public — expect them to do so. According to Jerome Herbert Skolnick, in dealing largely with disorderly elements of the society, some people working in law enforcement may gradually develop an attitude or sense of authority over society, particularly under traditional reaction-based policing models; in some cases the police believe that they are above the law.[37]

However, this "bad apple paradigm" is considered by some to be an "easy way out". A broad report commissioned by the Royal Canadian Mounted Police on the causes of misconduct in policing calls it "a simplistic explanation that permits the organization and senior management to blame corruption on individuals and individual faults – behavioural, psychological, background factors, and so on, rather than addressing systemic factors."[38] The report goes on to discuss the systemic factors, which include:

- Pressures to conform to certain aspects of "police culture", such as the Blue Code of Silence, which can "sustain an oppositional criminal subculture protecting the interests of police who violate the law"[39] and a "'we-they' perspective in which outsiders are viewed with suspicion or distrust"[38]

- Command and control structures with a rigid hierarchical foundation ("results indicate that the more rigid the hierarchy, the lower the scores on a measure of ethical decision-making" concludes one study reviewed in the report);[40] and

- Deficiencies in internal accountability mechanisms (including internal investigation processes).[38]

Police use of force is kept in check in many jurisdictions by the issuance of a use of force continuum.[41] A use of force continuum sets levels of force considered appropriate in direct response to a subject's behavior. This power is granted by the civil government, with limits set out in statutory law as well as common law.

Violence used by police can be excessive despite being lawful, especially in the context of political repression. Indeed "police brutality" is often used to refer to violence used by the police to achieve politically desirable ends and, therefore, when none should be used at all according to widely held values and cultural norms in the society (rather than to refer to excessive violence used where at least some may be considered justifiable).

Global prevalence

- The Amnesty International 2007 report on human rights also documents widespread police misconduct in many other countries, especially countries with authoritarian regimes.[1]

- In the UK, the reports into the death of New Zealand teacher and anti-racism campaigner Blair Peach in 1979 was published on the Metropolitan Police website on 27 April 2010. The conclusion was that Blair Peach was killed by a police officer, but that the other police officers in the same unit had refused to cooperate with the inquiry by lying to investigators, making it impossible to identify the actual killer.[citation needed]

- In the UK, Ian Tomlinson was filmed by an American tourist apparently being hit with a baton and then pushed to the floor, as he walked home from work during the 2009 G-20 London summit protests. Tomlinson then collapsed and died. Although he was arrested on suspicion of manslaughter, the officer who allegedly assaulted Tomlinson was released without charge.

- In Serbia, police brutality occurred in numerous cases during protests against Slobodan Milošević, and has also been recorded during protests against governments since Milošević lost power.[citation needed] The most recent case was recorded in July 2010, when five people, including two girls, were arrested, handcuffed and then beaten with clubs and otherwise mistreated for one hour. Security camera recordings of the beating were obtained by the media, causing public outrage.[42][43] The police officials, including Ivica Dačić, the Serbian minister of internal affairs, denied this sequence of events and accused the victims "to have attacked the police officers first". He also publicly stated that "police isn't here to beat up citizens", but that it is known "what one is going to get when attacking the police".[44]

- Some recent episodes of police brutality in India include the Rajan case, the death of Udayakumar,[45] and of Sampath.[46]

- Police violence episodes against peaceful demonstrators appeared during the 2011 Spanish protests.[47][48][49] Furthermore, in August 4, 2011, Gorka Ramos, a journalist of Lainformacion was beaten by police and arrested while covering 15-M protests near the Interior Ministry in Madrid.[50][51][52][53][54] A freelance photographer, Daniel Nuevo, was beaten by police while covering demonstrations against Pope's visit in August 2011.[55][56]

Investigation

In England and Wales, an independent organization known as the Independent Police Complaints Commission investigates reports of police misconduct. They automatically investigate any deaths caused by, or thought to be caused by, police action.

A similar body operates in Scotland, known as the Police Complaints Commissioner for Scotland. In Northern Ireland the Police Ombudsman for Northern Ireland has a similar role to that of the IPCC and PCCS.

Independent oversight

Various community groups have criticized police brutality. These groups often stress the need for oversight by independent citizen review boards and other methods of ensuring accountability for police action.

Umbrella organizations and justice committees (often named after a deceased individual or those victimized by police violence) usually engage in a solidarity of those affected. Amnesty International is another organization active in the issue of police brutality.

Tools used by these groups include video recordings, which are sometimes broadcast using websites such as YouTube.[57]

Citizens and communities have begun independent projects to monitor police activity in an effort to reduce violence and misconduct. These are often called "Cop Watch" programs.[58]

Proper supervision by competent police supervisors and administration can reduce police misconduct.

See also

- List of cases of police brutality

- List of cases of police brutality in the United States

- Police misconduct

- Police riot

- Prisoner abuse

- High Speed Pursuit Syndrome

- International Day Against Police Brutality (March 15)

- Legal observer

- List of killings by law enforcement officers in the United States

General:

US specific:

- Police brutality (United States)

- Police brutality cases (United States)

- Christopher Commission

- Copwatch

- Pitchess motion

References

- ^ a b "Amnesty International Report 2007". Amnesty International. 2007. Archived from the original on 2007-08-07. Retrieved 2007-08-08.

- ^ Oxford English Dictionary

- ^ "Police officers in trouble: Charges against policeman McManus by his sergeant". New York Times. June 23, 1893.

- ^ Johnson, Marilynn S. (2004). Johnson (ed.). Street Justice: A History of Police Violence in New York City. Beacon Press. p. 365. ISBN 0-8070-5023-7.

- ^ Powers, Mary D. (1995). "Civilian Oversight Is Necessary to Prevent Police Brutality". In Winters, Paul A. (ed.). Policing the Police. San Diego: Greenhaven Press. pp. 56–60. ISBN 1-56510-262-2.

- ^ Locke, Hubert G. (1966–1967). "Police Brutality and Civilian Review Boards: A Second Look" (Document). J. Urb. L. p. 625.

{{cite document}}: Unknown parameter|url=ignored (help); Unknown parameter|volume=ignored (help) - ^ Beliën, Paul (28 September 2006). "Brussels Returns to Normal, for Now". The Brussels Journal. Retrieved 31 August 2010.

- ^ Cite error: The named reference

BBC 28 September 2006was invoked but never defined (see the help page). - ^ a b Cite error: The named reference

BBCwas invoked but never defined (see the help page). - ^ "Paris rioters 'criminals' says PM". BBC News. 27 November 2007. Archived from the original on 29 November 2007. Retrieved 27 November 2007.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ Paris suburb riots after deaths of two teens in crash

- ^ Riots break out in Paris suburbs

- ^ a b Cite error: The named reference

premiersélémentswas invoked but never defined (see the help page). - ^ http://articles.cnn.com/2012-04-30/asia/world_asia_china-chen-internet_1_sina-weibo-chinese-censors-chen-guangcheng?_s=PM:ASIA

- ^ http://en.rsf.org/china-police-violence-against-28-02-2011,39643.html

- ^ http://www.economist.com/node/15731344

- ^ http://www.huffingtonpost.com/2012/03/29/russia-police-torture_n_1387421.html

- ^ http://www.economist.com/node/17419881

- ^ http://www.amnesty.org/en/news/indonesia-must-end-impunity-police-violence-2012-04-25

- ^ http://rabble.ca/news/2010/07/medics-g20-protests-speak-out-against-police-brutality-0

- ^ http://rabble.ca/news/2012/03/police-violence-rise-montreal

- ^ http://www.cpc-cpp.gc.ca/cnt/tpsp-tmrs/police/projet-pip-pep-eng.aspx

- ^ "Stockholm restaurant torched as riots spread". BBC. Retrieved 2013-05-26.

- ^ http://www.dw.de/sweden-sends-reinforcements-to-capital-after-fifth-night-of-rioting/a-16835451

- ^ http://online.wsj.com/article/SB10001424127887323975004578503260805490322.html

- ^ http://www.guardian.co.uk/world/2013/may/24/swedish-police-stockholm-rioting

- ^ http://www.thelocal.se/48196/20130528/

- ^ "Police attacked, use water cannons against protesters in Northern Ireland". The Washington Post. 5 January 2013. Retrieved 6 January 2013.

- ^ a b Cite error: The named reference

bbcqawas invoked but never defined (see the help page). - ^ Cite error: The named reference

autogenerated1was invoked but never defined (see the help page). - ^ "Kids are enjoying the riots too much to stop, says cleric". Belfast Telegraph, 12 January 2013

- ^ http://www.irishcentral.com/news/Police-patrols-protect-Catholic-Churches-in-Armagh-after-spate-of-attacks---VIDEO-190176591.html

- ^ http://www.breakingnews.ie/ireland/bomb-found-outside-antrim-church-could-be-linked-to-flags-protest-says-priest-586741.html

- ^ http://www.belfastdaily.co.uk/2013/02/03/revealed-renegade-loyalists-target-catholic-churches/

- ^ http://www.independent.ie/irish-news/union-flag-protests-cost-20m-29116278.html

- ^ "Police officers in trouble: Charges against policeman McManus by his sergeant". New York Times. June 23, 1893.

- ^ Skolnick, Jerome H. (1995). "Community-Oriented Policing Would Prevent Police Brutality". In Winters, Paul A. (ed.). Policing the Police. San Diego: Greenhaven Press. pp. 45–55. ISBN 1-56510-262-2.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ a b c Loree, Don (2006). "Corruption in Policing: Causes and Consequences; A Review of the Literature" (PDF). Research and Evaluation Community, Contract and Aboriginal Policing Services Directorate. Royal Canadian Mounted Police. Retrieved 2007-09-01.

- ^ Skolnick, Jerome H. (2002). "Corruption and the Blue Code of Silence". Police Practice and Research. 3 (1): 7. doi:10.1080/15614260290011309.

- ^ Owens, Katherine M. B. (2002). "Police Leadership and Ethics: Training and Police Recommendations". The Canadian Journal of Police and Security Services. 1 (2): 7.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ Stetser, Merle (2001). The Use of Force in Police Control of Violence: Incidents Resulting in Assaults on Officers. New York: LFB Scholarly Publishing L.L.C. ISBN 1-931202-08-7.

- ^ B92 (video)

- ^ Blic (video)

- ^ B92: Dačić: Police isn't here to beat up citizens

- ^ "Police question forensic experts". The Hindu. Chennai, India. 4 October 2005.

- ^ "Sampath case: 4 police officers to turn approvers". The Hindu. Chennai, India. 17 May 2011.

- ^ Spanish police clash with protesters over clean-up - The Guardian

- ^ Los Mossos d'Esquadra desalojan a palos la Plaza de Catalunya - Público Template:Es

- ^ Indignats - Desallotjament de la Plaça Catalunya on YouTube

- ^ Spanish riot police clash in Madrid with anti-austerity protesters - The Guardian

- ^ Los periodistas, detenidos y golpeados al cubrir las manifestaciones del 15-M - El Mundo Template:Es

- ^ Doce policías para detener a un periodista - Público Template:Es

- ^ Gorka Ramos: "Me tiraron al suelo, me patearon y luego me detuvieron" - Lainformación Template:Es

- ^ La policía detiene al periodista Gorka Ramos - El País Template:Es

- ^ Spanish police officer slaps girl during Pope protests - The Telegraph

- ^ La policía golpea a un fotógrafo y a una joven - Público Template:Es

- ^ Veiga, Alex (November 11, 2006). "YouTube.com prompts police beating probe". Associated Press. Retrieved 2006-11-12. [dead link]

- ^ Krupanski, Marc (March 7, 2012). "Policing the Police: Civilian Video Monitoring of Police Activity". The Global Journal. Retrieved 2012-03-13.

Further reading

- della Porta, D., A. Peterson and H. Reiter, eds. (2006). The Policing of Transnational Protest. Aldershot, Ashgate.

- della Porta, D. and H. Reiter (1998). Policing Protest: The Control of Mass Demonstrations in Western Democracies. Minneapolis, University of Minnesota Press.

- Donner, F. J. 1990. Protectors of Privilege: Red Squads and Police Repression in Urban America. Berkeley, University of California Press.

- Earl, Jennifer S. and Sarah A. Soule. 2006. “Seeing Blue: A Police-Centered Explanation of Protest Policing.” Mobilization 11(2): 145–164.

- McPhail, Clark, David Schweingruber, and John D. McCarthy (1998). “Protest Policing in the United States, 1960-1995.” pp. 49–69 in Policing Protest: The Control of Mass Demonstrations in Western Democracies, edited by D. della Porta and H. Reiter. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press.

- Oliver, P. (2008). “Repression and Crime Control: Why Social Movements Scholars Should Pay Attention to Mass Incarceration Rates as a Form of Repression” Mobilization 13(1): 1–24.

- Zwerman G, Steinhoff P. (2005). When activists ask for trouble: state-dissident interactions and the new left cycle of resistance in the United States and Japan. In Repression and Mobilization, ed. C. Davenport, H. Johnston, C. Mueller, pp. 85–107. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press.

External links

- World wide Police Brutalities archive

- Bringing awareness of Excessive Force, Malicious Prosecution and Police Brutality

- Names of Victims of Police Brutality In Canada

- Copwatch Project - includes the Copwatch Database: a permanent, searchable repository of complaints filed against police officers.

- [1] - information, statistics, and readings about state repression

- Cop Spotting - First-hand encounters with police abuse recorded on video.

- Policing the Police: Civilian Video Monitoring of Police Activity