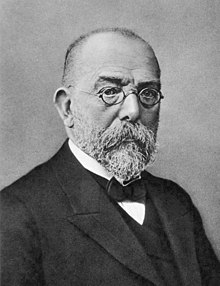

Robert Koch

Robert Koch | |

|---|---|

| |

| Born | 11 December 1843 |

| Died | 27 May 1910 (aged 66) |

| Nationality | German |

| Alma mater | University of Göttingen |

| Known for | Discovery bacteriology Koch's postulates of germ theory Isolation of anthrax, tuberculosis and cholera |

| Awards | Nobel Prize in Medicine (1905) |

| Scientific career | |

| Fields | Microbiology |

| Institutions | Imperial Health Office, Berlin, University of Berlin |

| Doctoral advisor | Friedrich Gustav Jakob Henle |

| Signature | |

| |

Robert Heinrich Herman Koch (December 11, 1843-May 27, 1910), considered to be the founder of modern bacteriology, is known for his role in identifying the specific causative agents of tuberculosis, cholera, and anthrax and for giving experimental support for the concept of infectious disease.[2] In addition to his pioneering studies on these diseases, Koch created and improved significant laboratory technologies and techniques in the field of microbiology, and made a number of key discoveries pertaining to public health.[3] His research led to the creation of Koch’s postulates, a series of four generalized principles linking specific microorganisms to particular diseases which remain today the “gold standard” in medical microbiology.[3] As a result of his groundbreaking research on tuberculosis, Koch received the Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine in 1905.[3]

Personal life

Robert Koch was born in Klausthal, Hanover, Germany on December 11, 1843 to Hermann Koch and Mathilde Julie Henriette Biewand.[4] Koch excelled in academics from an early age. Before entering school in 1848, Koch had taught himself how to read and write.[2] He graduated from high school in 1862, having excelled in science and math.[2] At the age of 19, Koch entered the University of Göttingen, studying natural science.[5] However, after two semesters, Koch decided to change his area of study to medicine, as he aspired to be a physician.[2] During Koch’s fifth semester of medical school, Jacob Henle, an anatomist who had published a theory of contagion in 1840, asked Koch to participate in his research project on uterine nerve structure.[2] In his sixth semester, Koch began to conduct research at the Physiological Institute, where he studied succinic acid secretion.[2] This would eventually form the basis of his dissertation.[3] In January 1866, Koch graduated from medical school, earning honors of the highest distinction.[2] In July 1867, following his graduation from medical school, Koch married Emma Adolfine Josephine Fraatz, and the two had a daughter, Gertrude, in 1868.[3] After his graduation in 1866, he worked as a surgeon in the Franco-Prussian War, and following his service, worked as a physician in Wollstein (now Wolsztyn, Poland).[5] Koch’s marriage with Emma Fraatz ended in 1893, and later that same year, he married actress Hedwig Freiberg.[3] From 1885 to 1890, Koch served as an administrator and professor at Berlin University.[2] Koch suffered a heart attack on April 9, 1910 and never made a complete recovery.[2] On May 27, only three days after giving a lecture on his tuberculosis research at the Berlin Academy of Sciences, Robert Koch died at Baden Baden at the age of 66.[5] Following his death, the Institute named its establishment after him in his honor.[2]

Research contributions

Anthrax

Robert Koch is widely-known for his work with anthrax, discovering the causative agent of the fatal disease to be Bacillus anthracis.[6] Koch discovered spore formation in the anthrax bacteria, which could remain dormant under specific conditions.[5] However, under optimal conditions, he found that the spores were activated and caused disease.[5] To determine this causative agent, he dry-fixed bacterial cultures onto glass slides, used dyes to stain the cultures, and then observed them through a microscope.[2] Koch’s work with anthrax is notable in that he was the first to link a particular microorganism with a given disease, rejecting the idea of spontaneous generation and proving the germ theory of disease.[6]

Koch's Four Postulates

Koch accepted a position as government advisor with the Imperial Department of Health in 1880.[7] During his time as government advisor, he published a report in which he stated the importance of pure cultures in isolating disease-causing organisms and explained the necessary steps to obtain these cultures, methods which are summarized in Koch’s four postulates.[8] Koch’s discovery of the causative agent of anthrax led to the formation of a generic set of postulates which can be used in the determination of the cause of any infectious disease.[6] These postulates, which not only outlined a method for linking cause and effect of an infectious disease but also established the significance of laboratory culture of infectious agents, are listed here: 1. The organism must always be present, in every case of the disease. 2. The organism must be isolated from a host containing the disease and grown in pure culture. 3. Samples of the organism taken from pure culture must cause the same disease when inoculated into a healthy, susceptible animal in the laboratory. 4. The organism must be isolated from the inoculated animal and must be identified as the same original organism first isolated from the originally diseased host.[6]

Isolating pure culture on solid media

Koch began conducting research on microorganisms in a laboratory that was connected to his patient examination room.[5] Koch’s early research in this laboratory proved to yield one of his major contributions to the field of microbiology, as it was there that he developed the technique of growing bacteria. Koch's second postulate calls for the isolation and growth of a selected pathogen in pure laboratory culture.[9] In an attempt to grow bacteria, Koch began to use solid nutrients such as potato slices.[9] Through these initial experiments, Koch observed individual colonies of identical, pure cells.[9] Coming to the conclusion that potato slices were not suitable media for all organisms, Koch later began to use nutrient solutions with gelatin.[9] However, he soon realized that gelatin, like potato slices, was not the optimal medium for bacterial growth, as it did not remain solid at 37˚C, the ideal temperature for growth of most human pathogens.[9] Therefore, Koch eventually began to utilize agar to grow and isolate pure cultures, as this polysaccharide remains solid at 37˚C, is not degraded by most bacteria, and results in a transparent medium.[9]

Cholera

Koch next turned his attention to cholera, and began to conduct research in Egypt in the hopes of isolating the causative agent of the disease.[5] However, Koch was not able to complete the task before the epidemic in Egypt ended, and he subsequently went to India to continue with his study.[2] In India, Koch was indeed able to determine the causative agent of cholera, isolating Vibrio cholera.[2]

Tuberculosis

During his time as the government advisor with the Imperial Department of Health in Berlin in the 1880s, Robert Koch became interested in tuberculosis research.[2] At the time, it was widely believed that tuberculosis was an inherited disease.[2] However, Koch was convinced that the disease was caused by a bacterium and was infectious, and tested his four postulates using guinea pigs.[2] Through these experiments, Koch found that his experiments with tuberculosis satisfied all four of his postulates.[2] In 1882, he published his findings on tuberculosis, in which he found the causative agent of the disease to be the slow-growing Mycobacterium tuberculosis.[9] His work with this particular disease won Koch the Nobel Prize in Physiology and Medicine in 1905.[2] Additionally, Koch's research on tuberculosis, along with his studies on tropical diseases, won him the Prussian Order Pour le Merits in 1906 and the Robert Koch medal, established to honor the greatest living physicians, in 1908.[2]

Timeline

References

- ^ Thomas D. Brock (1988). Robert Koch: A Life in Medicine and Bacteriology. ASM Press. p. 296. ISBN 9781555811433.

He loved seeing new things, but showed no interest in politics. Religion never entered his life.

{{cite book}}:|access-date=requires|url=(help) - ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s "Robert Koch." World of Microbiology and Immunology. Ed. Brenda Wilmoth Lerner and K. Lee Lerner. Detroit: Gale, 2006. Biography In Context. Web. 14 Apr. 2013.

- ^ a b c d e f "Brock, Thomas. Robert Koch: A life in medicine and bacteriology. ASM Press: Washington DC, 1999. Print.

- ^ Metchnikoff, Elie. The Founders of Modern Medicine: Pasteur, Koch, Lister. Classics of Medicine Library: Delanco, 2006. Print.

- ^ a b c d e f g "Heinrich Hermann Robert Koch." World of Scientific Discovery. Gale, 2006. Biography In Context. Web. 14 Apr. 2013.

- ^ a b c d "Germ theory of disease." World of Microbiology and Immunology. Ed. Brenda Wilmoth Lerner and K. Lee Lerner. Detroit: Gale, 2007. Biography In Context. Web. 14 Apr. 2013.

- ^ O’Connor, T.M. “Tuberculosis, Overview.” International Encyclopedia of Public Health. 2008. Web.

- ^ Amsterdamska, Olga. “Bacteriology, Historical.” International Encyclopedia of Public Health. 2008. Web.

- ^ a b c d e f g Madigan, Michael T., et al. Brock Biology of Microorganisms: Thirteenth edition. Benjamin Cummings: Boston, 2012. Print.

Further reading

- Brock, Thomas D. (1999). Robert Koch: A Life in Medicine and Bacteriology. Washington, D.C.: ASM Press. ISBN 978-1-55581-143-3. OCLC 39951653.

- Morris, Robert D (2007). The blue death: disease, disaster and the water we drink. New York: Harper Collins. ISBN 978-0-06-073089-5. OCLC 71266565.

- Gradmann, Christoph (2009). Laboratory Disease: Robert Koch's Medical Bacteriology. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press. ISBN 978-0-8018-9313-1.

- Weindling, Paul. "Scientific elites and laboratory organization in fin de siècle Paris and Berlin: The Pasteur Institute and Robert Koch’s Institute for Infectious Diseases compared," in Andrew Cunningham and Perry Williams, eds. The Laboratory Revolution in Medicine (Cambridge University Press, 1992) pp: 170–88.

External links

- Robert Koch Biography at the Nobel Foundation website

- MPIWG-Berlin, Robert Koch Biography and bibliography in the Virtual Laboratory of the Max Planck Institute for the History of Science

- Musoptin.com, original microscope out of the laboratory Robert Koch used in Wollstein (1877)

- Musoptin.com, microscope objectives: as they were used by Robert Koch for his first photos of microorganisms (1877–1878)

Texts on Wikisource:

Texts on Wikisource:

- "Koch, Robert". Encyclopedia Americana. 1920.

- Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). "Koch, Robert". Encyclopædia Britannica (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press.

- Gilman, D. C.; Peck, H. T.; Colby, F. M., eds. (1905). New International Encyclopedia (1st ed.). New York: Dodd, Mead.

{{cite encyclopedia}}: Missing or empty|title=(help)

- Use dmy dates from July 2011

- 1843 births

- 1910 deaths

- People from Goslar (district)

- Deaths from myocardial infarction

- German biologists

- German inventors

- German microbiologists

- German military personnel of the Franco-Prussian War

- German Nobel laureates

- German physicians

- Humboldt University of Berlin faculty

- Members of the Prussian Academy of Sciences

- Members of the Royal Swedish Academy of Sciences

- Nobel laureates in Physiology or Medicine

- People from the Kingdom of Hanover

- Phthisiatrists

- Recipients of the Pour le Mérite (civil class)

- Tuberculosis

- University of Göttingen alumni

- Foreign Members of the Royal Society