Billy the Kid

Billy the Kid | |

|---|---|

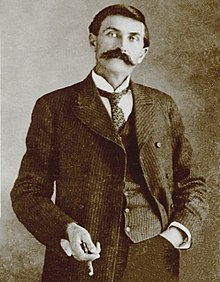

Billy the Kid posing for a ferrotype photograph | |

| Born | Henry McCarty September 17, 1859 New York City |

| Died | July 14, 1881 (buried July 15, 1881) |

| Cause of death | Gunshot wound from Pat Garrett |

| Resting place | 34°24′13″N 104°11′37″W / 34.40361°N 104.19361°W |

| Other names | William H. Bonney, Henry Antrim, Kid Antrim |

| Occupation(s) | Horse rustler, cowboy, gambler, outlaw |

| Height | 5 ft 8 in (173 cm) |

| Parents |

|

| Relatives | Brother: Joseph McCarty |

Henry McCarty (September 17, 1859 –July 14, 1881), better known under the pseudonyms of Billy the Kid and William H. Bonney, was a 19th-century gunman who participated in the Lincoln County War and became a frontier outlaw in the American Old West. According to legend, he killed twenty-one men,[1] but it is now generally believed that he killed eight,[1] with the first on August 17, 1877.[2]

McCarty was 5 ft 8 in (173 cm) tall with blue eyes, blond or dirty blond hair, and a smooth complexion. He was described as being friendly and personable at times,[3][4] and as lithe as a cat.[3] Contemporaries described him as a "neat" dresser who favored an "unadorned Mexican sombrero".[3][5] These qualities, along with his cunning and celebrated skill with firearms, contributed to his paradoxical image as both a notorious outlaw and a folk hero.[1]

He was relatively unknown during most of his lifetime, but was catapulted into legend in 1881 when New Mexico's governor Lew Wallace placed a price on his head. In addition, the Las Vegas Gazette (Las Vegas, New Mexico) and the New York Sun carried stories about his exploits.[6] Other newspapers followed suit. Several biographies written about the Kid after his death portrayed him in varying lights.[6]

Early life

New York City

The birth of Billy the Kid remains the subject of debate. Robert M. Utley, one of the leading Billy the Kid researchers, paid tribute to three historians who had "tracked Billy the Kid through public records and stripped away much of the myth."[7] Utley cited the work of Philip J. Rasch,[8] as well as Robert N. Mullin, who later co-authored a landmark article with Rasch.[9] Finally, Utley cited an article by Jack DeMattos, written in 1980, which was the first one to provide documentary evidence of Billy the Kid's birth, baptism, and residence in New York City.[10]

The story of Billy the Kid began on June 15, 1851 when 21-year-old Patrick McCarty married 20-year-old Catherine Devine. The ceremony was performed at the Church of St. Peter at 16 Barclay Street in New York City. The Rev. M.A. Madden performed the ceremony. The first of three children born to this union was Bridget McCarty in 1853. The second and most celebrated of the McCarty children was born at 210 Greene Street in New York City on September 17, 1859. He was christened Henry McCarty on September 28, 1859 at the same church where his parents had been married. His godparents were Thomas Cooney and Mary Clark.[11]

The next documentation concerning the future "Billy the Kid" and his family was provided on June 26, 1860 when they were enumerated on the census for that year by Assistant Marshal Edward Hogan of New York City. Hogan misspelled their surnames as "McCarthy" rather than "McCarty," but there is no doubt that these Manhattan First Ward residents were the same McCarty family who resided at 210 Greene Street. They were listed as: Patrick McCarthy [sic], age 30, born United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland; Catherine McCarthy [sic], age 29, born United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland; Bridget McCarthy [sic], age 7, born New York; and Henry McCarthy [sic], age 1, born New York.[12]

The 1860 New York City Directory did manage to get the family's surname correct. That directory only recorded the head of a household's name, and listed Patrick McCarty, "day laborer," as living at "210 Greene Street."[13] The surname spelling was confused again in the 1863 New York City Directory, which listed "Patrick McCarthy" [sic] as living at 210 Greene Street. This was also the last listing for the father of Billy the Kid.[14]

The final McCarty child was born at 210 Greene Street on October 14, 1863. He was born Joseph McCarty, but later took his stepfather's surname and was known for most of his life as "Joseph Antrim." He was routinely identified by historians as Billy the Kid's older brother. That theory was based on a death certificate which suggested that he was born in 1854, rather than the correct year of 1863. That theory persisted for years, until other documents were uncovered which proved that the 1863 birth date was the correct one. One of the earliest supporting documents was an 1880 U.S. Census record in which Joseph Antrim gave his age as seventeen and his birthplace as New York.[15] On an 1885 Colorado State Census for Arapahoe County, Joseph Antrim gave his age as 21, which he still was in the summer of 1885 when the census was taken.[16]

Patrick McCarty died shortly after the birth of his third child. The cause of his death has not yet been learned. All that is known is that he was last listed in the 1863 New York City Directory. The following year marked the only appearance of his widow as being the head of a family living at 210 Greene Street. In that 1864 city directory, she was listed as "Catherine McCarty, widow of Patrick."[17]

Indianapolis

No solid documentation has been yet uncovered for the McCarty family's exact whereabouts between late 1864 (when they were last listed in New York City) and the summer of 1870 (when they turned up in Kansas). Some historians have suggested an 1868 Indianapolis residence, due to a city directory listing of "Catherine McCarty, widow of Michael" living at 199 North East Street recorded that year.[18] However, it seems unlikely for this person to be Billy the Kid's mother, considering the New York listing for her as the "widow of Patrick".[19]

Wichita

The first time that the McCarty family can be located again with any certainty is August 10, 1870 when they settled in Kansas. On September 12, 1870 Mrs. Catherine McCarty was given title to a vacant lot in Wichita.[20] During February 1871, William Henry Harrison Antrim was given title to lots adjoining those of Mrs. Catherine McCarty in Wichita. Then, on March 25, 1871, Mrs. McCarty paid $200 for a quarter section of land at the going price of $1.25 per acre. To support her claim, Antrim submitted a sworn statement that read in part: "I have known Catherine McCarty for 6 years last past; that she is a single woman over the age of twenty-one years, the head of a family consisting of two children and a citizen of the United States."[21]

New Mexico

Both the McCarty family and Antrim next turn up on March 1, 1873 in Santa Fe, New Mexico. On that date, William Henry Harrison Antrim married Catherine Devine McCarty at Santa Fe's First Presbyterian Church. They were married by a minister named David F. McFarland. The witnesses were Harvey Edmonds, Mrs. A.R. McFarland, her daughter Katie, and the bride's two sons, 13 year-old Henry and 9 year-old Joseph, who was called "Josie."[22] Shortly after the ceremony, the family moved from Santa Fe to Silver City, New Mexico. Eighteen months after her second marriage, on September 16, 1874, Catherine Devine McCarty Antrim died. The only known obituary for Billy the Kid's mother appeared three days later:

- "Died in Silver City, on Wednesday the 16th inst., Catherine, wife of William Antrim, aged 45 years. Mrs. Antrim and her husband and family came to Silver City about one year and a half ago, since which time her health has not been good, having suffered from an affliction of the lungs. For the last four months she has been confined to her bed. The funeral occurred from the family residence on Main Street, at 2 o'clock on Thursday."[23]

Henry McCarty had his first known run-in with the law exactly one year after his mother's death, and just one day before his sixteenth birthday. A Silver City newspaper gave this report of the event:

- "Henry McCarty, who was arrested on Thursday [September 16, 1875] and committed to jail to await the action of the Grand Jury upon the charge of stealing clothes from Charley Sun and Sam Chung, celestials, sans cues, sans joss sticks, escaped from prison yesterday through the chimney. It's believed that Henry was simply the tool of "Sombrero Jack," who done the stealing while Henry done the hiding. Jack has skinned out."[24]

First major crimes

According to some accounts, McCarty eventually found work as an itinerant ranch hand and shepherd in southeastern Arizona.[25] In 1876, McCarty settled in the vicinity of the Fort Grant Army Post in Arizona where he worked on ranches and tested his skills at local gaming houses.[26]

During this time, he became acquainted with John R. Mackie, a Scottish-born ex-cavalry private with a criminal bent.[27] The two men supposedly became involved in the risky but profitable enterprise of horse thievery. McCarty stole from local soldiers and became known by the name of "Kid Antrim".[28] Biographer Robert M. Utley writes that the nickname arose because of McCarty's slight build and beardless countenance, his young years, and his appealing personality.[29]

The future "Billy the Kid" managed to keep out of the news for nearly two years. His next press clipping came from Arizona, where he killed his first documented victim Frank P. Cahill on August 17, 1877. He was exactly one month shy of his eighteenth birthday. A Tucson paper gave this account of the killing:

- "Austin [sic] Antrim shot F.P. Cahill near Camp Grant on the 17th instant, and the latter died on the 18th. Cahill made a statement before his death to the effect that he had some trouble with Antrim during which the shooting was done ... The coroner's jury found that the shooting 'was criminal and unjustifiable,' and that 'Henry Antrim, alias Kid, is guilty thereof.' The inquest was held by M.L. Wood, J.P., and the jurors were M. McDowell, Geo. Teague, T. McCleary, B.E. Norton, Jas. L. Hunt and D.H. Smith."[30]

In fear of Cahill's friends, McCarty fled the Arizona Territory and entered into New Mexico Territory.[31] He eventually arrived at the former army post of Apache Tejo, where he joined a band of cattle rustlers who raided the sprawling herds of cattle magnate John Chisum.[32] During this period, McCarty was spotted by a resident of Silver City, and the teenager's involvement with the notorious gang was mentioned in a local newspaper.[32] McCarty rode for a time with the gang of rustlers known as the Jesse Evans Gang, but then turned up at Heiskell Jones's house in Pecos Valley, New Mexico.[33][34]

According to this account, Apaches stole McCarty's horse, forcing him to walk many miles to the nearest settlement, which happened to be Jones's home. When he arrived, the young man was supposedly near death, but Mrs. Jones nursed him back to health.[34] The Jones family developed a strong attachment to McCarty and gave him one of their horses.[34] At some point in 1877, McCarty began to refer to himself as "William H. Bonney".[35]

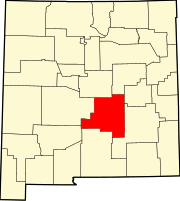

Lincoln County War

In 1877, McCarty (now widely known as William Bonney) moved to Lincoln County, New Mexico and was hired by Doc Scurlock and Charlie Bowdre to work in their cheese factory.[36] Through them, he met Frank Coe, George Coe, and Ab Saunders, three cousins who owned their own ranch near the ranch of Richard M. Brewer.

Late in 1877, McCarty, Brewer, Bowdre, Scurlock, the Coes, and Saunders were hired by John Tunstall, an English cattle rancher, banker, and merchant, and his partner Alexander McSween, a prominent lawyer, to drive and guard cattle due to their proficiency with firearms.[37]

The conflict known today as the Lincoln County War had erupted between established town merchants Lawrence Murphy and James Dolan, versus competing business interests headed by Tunstall and McSween.[37] Before the arrival of Tunstall and McSween, Murphy and Dolan presided over a monopoly of Lincoln County's cattle and merchant trade; their far-reaching operation was known locally as "The House", after a large mansion in Lincoln that served as Murphy and Dolan's headquarters. There was also an ethnic element to the House's conflict with Tunstall: Murphy and Dolan were both Irish immigrants and were strongly opposed to an Englishman like Tunstall cutting into their business.[38]

Events turned bloody on February 18, 1878 when Tunstall was spotted driving a herd of nine horses towards Lincoln and was murdered by a posse composed of William Morton, Tom Hill, Frank Baker, Jesse Evans, and Lincoln County Sheriff William J. Brady – who had been sent to attack McSween's holdings.[37] After murdering Tunstall, the gunmen shot his prized bay horse.[39] "As a wry and macabre joke on Tunstall's great affection for horses, the dead bay's head was then pillowed on his hat", writes Frederick Nolan, Tunstall's biographer.[40] Members of the House sought to portray Tunstall's death as a "justifiable homicide", but evidence at the scene suggested that Tunstall attempted to avoid a confrontation before he was shot down.[41] Tunstall's murder enraged McCarty and the other ranch hands.[37]

McSween abhorred violence and took steps to punish Tunstall's murderers through legal means, obtaining warrants for their arrests from local justice of the peace John B. Wilson.[37] Tunstall's men formed their own group called the Regulators.[42] Tunstall's foreman Brewer had been appointed a special constable and given a warrant to arrest the murderers of Tunstall. He deputized the Regulators, and they then proceeded to the Murphy-Dolan store.[43] Two of the wanted men, Bill Morton and Frank Baker, attempted to flee, but they were captured on March 6. Upon returning to Lincoln, the Regulators reported that Morton and Baker had been shot on March 9, near Agua Negra during an alleged escape attempt.[43][44][45] During their journey to Lincoln, the Regulators killed one of their members, a man surnamed McCloskey, whom they suspected of being a traitor.[43][45][46]

Governor Samuel Beach Axtell arrived in Lincoln County on the day that McCloskey, Morton, and Baker were slain, in order to investigate the ongoing violence. The governor, accompanied by James Dolan and associate John Riley, proved hostile to the faction now headed by McSween. The Regulators "went from lawmen to outlaws".[43] Axtell refused to acknowledge the so-called "Santa Fe Ring", a group of corrupt politicians and business leaders led by U.S. Attorney Thomas Benton Catron.[47] Catron cooperated closely with the House, which was perceived as part of the notorious "ring".[48]

The Regulators planned to settle a score with Sheriff William J. Brady, who had arrested McCarty and fellow deputy Fred Waite in the aftermath of Tunstall's murder. At the time when Brady arrested them, the two men were trying to serve a warrant on him for his suspected role in looting Tunstall's store after the Englishman's death, as well as against his posse members for the murder of Tunstall.[37] On April 1, the Regulators (Jim French, Frank McNab, John Middleton, Fred Waite, Henry Brown, and McCarty/Bonney) ambushed Sheriff Brady[49] and his deputy George W. Hindman,[50] killing them both in Lincoln's main street.

McCarty was shot in the thigh while attempting to retrieve a rifle that Brady had seized from him during an earlier arrest.[46] With this move, the Regulators disillusioned many former supporters, who came to view both sides as "equally nefarious and bloodthirsty".[51] The connection was ambiguous between McSween and the Regulators, however. McCarty was loyal to the memory of Tunstall, though not necessarily to McSween.[52] Jacobsen doubts whether McCarty and McSween were acquainted at the time of Brady's death. According to a contemporary newspaper account, the Regulators disclaimed "all connection or sympathy with McSween and his affairs" and expressed that their sole desire was to track down Tunstall's murderers.[52]

On April 4, in what became known as the Gunfight of Blazer's Mills, the Regulators sought the arrest of Buckshot Roberts, a former buffalo hunter whom they suspected of involvement in the Tunstall murder.[53] Roberts refused to be taken alive, although he suffered a severe bullet wound to the chest.[54] During the gun battle, he shot and killed the Regulators' leader Dick Brewer.[53][55] Four other Regulators were wounded in the skirmish.[46] The incident had the effect of further alienating the public, as many local residents "admired the way Roberts put up a gutsy fight against overwhelming odds."[56]

Killing of Frank McNab and after

After Brewer's death, the Regulators elected Frank McNab as captain. For a short period, the Regulators benefited from the appointment of Sheriff John Copeland, who proved sympathetic to their cause. Copeland's authority was undermined by the House, which recruited members from among Brady's former deputies. Meanwhile, the Jesse Evans gang formed a posse together with the Seven Rivers Warriors, who were under the direction of former Brady deputy George W. Peppin. On April 29, 1878, this posse engaged in a shootout at the Fritz Ranch against McNab, Ab Saunders, and Frank Coe. They killed McNab, severely wounded Saunders, and captured Frank Coe—though Coe managed to escape from custody a short time later.[56]

The next day, the Regulators took up defensive positions in the town of Lincoln, where they traded shots with Dolan's men as well as U.S. cavalrymen.[56] The only casualty was Dutch Charley Kruling, a House gunman wounded by a rifle slug fired by George Coe.[57] By shooting at US government troops, the Regulators gained a new set of enemies. On May 15, the Regulators tracked down Seven Rivers Warriors gang member Manuel Segovia, the suspected murderer of Frank McNab, and killed him.[58] Around the time of Segovia's death, the Regulators gained a new member, a young Texas "cowpoke" named Tom O'Folliard, who became McCarty's close friend and constant companion.[58]

The Regulators' position worsened when the governor removed Copeland, in a quasi-legal move, and appointed House ally George Peppin as sheriff.[58] McCarty and the other Regulators were under indictment for the Brady killing, and they spent the next several months in hiding. They were trapped on July 15 in McSween's home (along with McSween) in Lincoln by members of the House and some of Brady's men.[58] On July 19, a column of U.S. cavalry soldiers entered the fray. The soldiers were ostensibly neutral, but their actions favored the Dolan faction.[59] After a five-day siege, the posse set McSween's house on fire,[59] and McCarty and the other Regulators fled. The posse shot McSween when he escaped the fire, essentially marking the end of the Lincoln County War.[59]

Lew Wallace and amnesty

In the Autumn of 1878, President Rutherford B. Hayes appointed Lew Wallace as Governor of the New Mexico Territory.[60] (Wallace was a former Union Army general.) In an effort to restore peace to Lincoln County, Wallace proclaimed an amnesty for any man involved in the Lincoln County War who was not already under indictment.[60] McCarty had fled to Texas after his escape from McSween's house and was already under indictment, but he sent Wallace a letter requesting immunity in return for testifying in front of the Grand Jury.[61] In March 1879, Wallace and McCarty met in Lincoln County to discuss the possibility of a deal. McCarty greeted the governor with a revolver in one hand and a Winchester rifle in the other.[62] After taking several days to consider Wallace's offer, McCarty agreed to testify in return for amnesty.[61]

The arrangement called for McCarty to submit to a token arrest and a short stay in jail until the conclusion of his courtroom testimony.[61] McCarty's testimony did help to indict John Dolan, but the district attorney disregarded Wallace's order to set McCarty free after his testimony (the district attorney was one of the powerful "House" faction leaders).[63] After the Dolan trial, McCarty and O'Folliard escaped on horses supplied by friends.[63]

For the next year and a half, McCarty survived by rustling, gambling, and taking defensive action. In January 1880, he reportedly killed a man named Joe Grant in a Fort Sumner saloon.[64] Grant did not realize who his opponent was and boasted that he would kill "Billy the Kid" if he ever encountered him. In those days, men loaded their revolvers with only five rounds, with the hammer down on an empty chamber. This was done to prevent an accidental discharge should the hammer be struck. The Kid asked Grant if he could see his ivory-handled revolver and, while looking at the weapon, rotated the cylinder so that the hammer would fall on the empty chamber when the trigger was pulled. He then told Grant his identity. When Grant fired, nothing happened, and McCarty shot him. When asked about the incident later, he remarked, "It was a game for two, and I got there first."[64]

Other versions of this story exist. Biographer Joel Jacobsen recounts the story describing Grant as a "drunk" who was "making himself obnoxious in a bar".[65] "The Kid" is described as rotating the cylinder "so an empty chamber was beneath the hammer".[65] In Jacobsen's recounting of the incident, Grant tried to shoot McCarty in the back. "As [McCarty] was leaving the saloon, his back turned to Grant, he heard a distinct click. He spun around before Grant could reach a loaded chamber. Always a good marksman, he shot Grant in the chin."[65]

In November 1880, a posse pursued and trapped the Kid's gang inside a ranch house owned by his friend James Greathouse at Anton Chico in the White Oaks area.[66] James Carlysle[67] of the posse entered the house under a white flag, in an effort to negotiate the group's surrender.[66] Greathouse was sent out to act as a hostage for the posse.[68] At some point in the evening, Carlysle evidently decided that the outlaws were stalling. According to one version, Carlysle heard a shot that had been accidentally fired outside, concluding that the posse had shot down Greathouse. He chose escape, crashed through a window, and was fired upon and killed.[66] Recognizing their mistake, the posse became demoralized and scattered, enabling McCarty and his gang to slip away. McCarty vehemently denied shooting Carlysle, and later wrote to Governor Wallace, claiming to be innocent of this crime and others which had been attributed to him.[66]

Pat Garrett

During this time, McCarty became acquainted with an ambitious local bartender and former buffalo hunter named Pat Garrett.[64] Popular accounts often depict McCarty and Garrett as "bosom buddies", but there is no evidence that they were actual friends.[66] Garrett was elected as sheriff of Lincoln County in November 1880, running on a pledge to rid the area of rustlers. In early December, he assembled a posse and set out to arrest McCarty, by that time known almost exclusively as "Billy the Kid." The Kid carried a $500 bounty on his head that had been authorized by governor Lew Wallace.[66][69]

Garrett's posse fared well, and his men closed in quickly. On December 19, McCarty barely escaped a midnight ambush in Fort Sumner, which left gang member Tom O'Folliard dead.[66] On December 23, the Kid was tracked to an abandoned stone building in a remote location known as "Stinking Springs" (near present-day Taiban, New Mexico). Garrett's posse surrounded the building while McCarty and his gang were asleep inside, and waited for sunrise. The next morning, a cattle rustler named Charlie Bowdre stepped outside to feed his horse.[70] He was mistaken for McCarty and was shot down by the posse.[70]

Soon afterwards, somebody from within the building reached for the horse's halter rope, but Garrett shot and killed the horse, whose body blocked the building's only exit.[71] The lawmen then began to cook breakfast over an open fire, and Garrett and McCarty engaged in a friendly exchange. Garrett invited McCarty outside to eat, and McCarty invited Garrett to "go to hell." Realizing that they had no hope of escape, the besieged and hungry outlaws finally surrendered and were allowed to join in the meal.[71]

Escape from Lincoln

The Kid was transported from Fort Sumner to Las Vegas, where he gave an interview to a reporter from the Las Vegas Gazette.[72] Next, the prisoner was transferred to Santa Fe, where he sent four separate letters over the next three months to Governor Wallace seeking clemency. Wallace refused to intervene,[72] and the Kid's trial was held in April 1881 in Mesilla.[73] The Kid was found guilty on April 9 of the murder of Sheriff Brady, after two days of testimony, the only conviction ever secured against any of the combatants in the Lincoln County War. On April 13, he was sentenced by Judge Warren Bristol to hang, with his execution scheduled for May 13.[73]

The Kid was removed to Lincoln, where he was held under guard on the top floor of the town courthouse by two of Garrett's deputies, Bob Olinger and James Bell. The Kid killed both guards and escaped on April 28, while Garrett was out of town.[74]

Deputy James Bell reportedly showed the Kid respect and "never, by word or action, did he betray his prejudice if it existed".[75] Deputy Olinger reportedly treated the Kid badly. Olinger's favorite weapon and tool of choice when tormenting the Kid was his double-barreled shotgun. He had loaded it with buckshot and was overconfident in his abilities as a guard. On April 28, 1881, Olinger left the prison for lunch, leaving his shotgun in Bell's custody. The Kid got his hands on a gun somehow and shot Bell, fatally wounding him.[76] It is not clear how the gun came into the Kid's possession, though various theories have been suggested. The Kid himself later claimed that he never wanted to kill Bell, but the other man stood in the way of his escape.

The second guard was across the street with some other prisoners, and the Kid waited at the upstairs window for him to respond to the gunshot and come to Bell's aid. As Olinger came running into view, the Kid leveled the shotgun at him, called out "Hello Bob!", and shot him dead.[74][77] The site of these killings is preserved in Lincoln County with the hole in the wall on display where Bell was shot, as well as a plaque where Olinger was gunned down.[78] His escape was delayed for an hour while he worked himself free of his leg irons[79] with an axe. Then he mounted a horse and rode out of town, reportedly singing.[74] The horse returned two days later.[80]

Death

Sheriff Pat Garrett responded to rumors that McCarty was lurking in the vicinity of Fort Sumner almost three months after his escape. Garrett and two deputies set out on July 14, 1881 to question one of the town's residents, a friend of McCarty's named Pete Maxwell (son of land baron Lucien Maxwell).[80] Close to midnight, Garrett and Maxwell sat talking in Maxwell's darkened bedroom when McCarty unexpectedly entered the room.[81]

There are at least two versions of what happened next. One version suggests that, as the Kid entered, he failed to recognize Garrett in the poor light. He drew his revolver and backed away, asking "¿Quién es? ¿Quién es?" (Spanish for "Who is it? Who is it?").[81] Recognizing McCarty's voice, Garrett drew his own revolver and fired twice, the first bullet striking McCarty in the chest just above his heart, although the second one missed and struck the mantel behind him. McCarty fell to the floor, gasped for a minute, and died.[81]

In the second version, McCarty entered carrying a knife, evidently heading for a kitchen area. He noticed someone in the darkness, and uttered the words, "¿Quién es? ¿Quién es?" at which point he was shot and killed. The popularity of the first story persists and portrays Garrett in a better light, although some historians contend that the second version is probably the accurate one.[82]

Garrett allowed the Kid's friends to take his body across the plaza to the carpenter's shop to give him a wake. The next morning, Justice of the Peace Milnor Rudulph viewed the body and made out the death certificate, but Garrett rejected the first one and demanded that another one be written more in his favor. The Kid's body was then prepared for burial, and was buried at noon at the Fort Sumner cemetery between O'Folliard and Bowdre.[83]

In his book Billy the Kid: A Short and Violent Life, Robert Utley tells the story of Pat Garrett's book effort. In the weeks following the Kid's death, Garrett felt the need to tell his side of the story. Many people had begun to talk about the unfairness of the encounter, so Garrett called upon his friend Marshall Ashmun (Ash) Upson to ghostwrite a book with him.[84] Upson was a roving journalist who had a gift for graphic prose. Their collaboration led to a book entitled The Authentic Life of Billy, the Kid which was first published in April 1882. The book originally sold few copies, but it eventually proved to be an important reference for historians who later wrote about the Kid's life.[84]

Rumors of survival

Legends grew over time that Billy the Kid was not killed that night, but that Garrett may have staged it all out of friendship for the Kid so that he could escape the law.[85][86] In the years after 1881, several men came forward to claim that they were the real Kid, who escaped Garrett's bullets. Most of them were easily and immediately debunked and their names lost to history, but there are two who remain topics of discussion and debate for one reason or another. The first of these claimants is Brushy Bill Roberts, a name familiar to most Billy the Kid researchers, and the claimant who has easily received the bulk of press. The second claimant, however, one John Miller, has received comparatively little notoriety, either in life or posthumously. In 2004, researchers sought to exhume the remains of Catherine Antrim, McCarty's mother, "so her DNA could be tested and compared with DNA to be taken from the body buried under the Kid's gravestone".[86] Ultimately, the case was bogged down in the courts, "much to the delight of New Mexico Governor Bill Richardson, who knows all too well the value of Billy as a cultural icon and a draw for tourists".[86]

Brushy Bill Roberts

In 1948, a paralegal named William Morrison located a man in Central Texas known as Ollie Partridge Roberts (nicknamed Brushy Bill), who admitted in private to being Billy the Kid and challenged the popular account of McCarty as shot to death by Pat Garrett in 1881.[87][88] Brushy Bill later claimed that "Ollie Partridge Roberts" was an assumed name, which accounted for the discrepancies in birth dates and physical appearance between Ollie Roberts and Billy the Kid. Roberts' claim has been rejected by almost all historians and even by his own niece, but there was evidence suggesting that his claim may have had some substance. Five people who had known Billy the Kid signed affidavits that they believed Roberts and the Kid were one and the same.[89] The town of Hico, Texas (Brushy Bill's residence) has capitalized on the Kid's infamy by opening the "Billy The Kid Museum".[90] Brushy Bill's story was further promoted by the 1990 film Young Guns II, as well as a 2011 episode of Brad Meltzer's Decoded on the History Channel. Robert Stack did a segment on Brushy Bill in early 1990 on the NBC television series Unsolved Mysteries.

Numerous books have also been published since 1950 advancing Brushy's claim, the first of which was Alias Billy the Kid written by Morrison and renowned western historian C.L. Sonnichsen. This book received mixed reviews at the time but did win support from former President Harry S. Truman, who wrote to Morrison indicating that he believed that Brushy was Billy the Kid and lamenting that he died before being able to go in front of the next governor, where he may have gotten a more favorable result.[91] In October 2014, new information was published in the book Billy the Kid: An Autobiography, which included military and genealogical records that supported certain aspects of Brushy Bill's story. A new photographic comparison of a young Brushy Bill with the Billy the Kid ferrotype image was included, as well as a photo of him serving with the Rough Riders just as he had claimed.[92] In April 2015, media personality Bill O'Reilly weighed in on the topic by publishing his book Bill O'Reilly's Legends and Lies: The Real West. O'Reilly suggests that the evidence in favor of Brushy Bill Roberts outweighs the accepted version of history, citing the original Alias Billy the Kid book by Morrison and Sonnichsen. O'Reilly followed up his book with an episode on the subject during his national television broadcast depicting the events that occurred during the alleged killing of the Kid from Brushy Bill's perspective.

John Miller

Another individual who claimed to be Billy the Kid was John Miller, whose family supported his claim in 1938, some time after Miller's death. Miller was buried at the state-owned Pioneers' Home Cemetery in Prescott, Arizona. Tom Sullivan, a former sheriff of Lincoln County, and Steve Sederwall, a former mayor of Capitan, disinterred the bones of John Miller in May 2005.[93] Sederwall and Sullivan believed that the exhumation was allowed, but official permission had not been given.[94] DNA samples from the remains were sent to a lab in Dallas, Texas, to be compared with traces of blood obtained from a bench that was believed to be the one upon which McCarty's body was placed after he was shot to death. The two investigators had searched for McCarty's physical remains since 2003. They started in Fort Sumner, New Mexico and eventually ended up in Arizona. To date, no DNA test results have been made public. As of 2008, a lawsuit is pending against officials in Lincoln County that would, if successful, publicize the results of those tests along with other evidence that Sullivan and Sederwall collected.[95]

Notoriety

Like many gunfighters of the "Old West", Billy the Kid enjoyed a reputation built partly on exaggerated accounts of his exploits.[96] McCarty was credited with killing between 15 and 26 men, depending on varying sources.[74][97][98] Wallis has speculated that the Dolan faction created the Kid's image to distract the public's attention from their activities and those of their influential supporters in Santa Fe, notably the regional political leader Thomas Benton Catron.[96]

The notoriety that McCarty gained during the Lincoln County War effectively doomed his appeals for amnesty.[99] A number of the Regulators faded away or secured amnesty, but McCarty could not accomplish either. His negotiations for amnesty came to nothing with governor Lew Wallace (a famed Civil War general and author of the novel Ben-Hur: A Tale of the Christ). A string of negative newspaper editorials referred to him as "Billy the Kid".[99] When a reporter reminded Wallace that the Kid was depending on the governor's intervention, the governor supposedly smiled and said, "Yes, but I can't see how a fellow like him can expect any clemency from me."[72]

Firsthand accounts of character

Various accounts recorded by friends and acquaintances describe him as fun-loving and jolly, articulate in both his writing and his speech, and loyal to those for whom he cared.[100] He was fluent in Spanish, popular with Latina girls, an accomplished dancer, and well loved in the territory's Hispanic community.[1] "His many Hispanic friends did not view him as a ruthless killer but rather as a defender of the people who was forced to kill in self-defense", Wallis writes. "In the time that the Kid roamed the land he chided Hispanic villagers who were fearful of standing up to the big ranchers who stole their land, water, and way of life."[1]

Photographic images

One of the few remaining artifacts of McCarty's life is a 2x3 inch ferrotype taken by an unknown photographer sometime in late 1879 or early 1880. It is the only image of McCarty that scholars agree is authentic.[101] The ferrotype survived because Dan Dedrick, one of Billy's rustler friends, held onto the picture after Billy's death, and passed it down in his family. The ferrotype appeared in several copied forms before the original was made public in the mid-1980s by Stephen and Art Upham, descendants of Dedrick. It was displayed for several years in the Lincoln County Heritage Trust Museum before it was withdrawn again.

The ferrotype sold at auction on June 25, 2011, in a three-day Western show. It was purchased for $2.3 million by billionaire William Koch, some six times the estimate.[102] It was the most expensive piece ever sold at Brian Lebel's Annual Old West Show & Auction,[103] and the seventh most expensive photograph ever sold.

The photograph of The Kid, commonly known as the Upham tintype – after its longtime owner Frank Upham – was the subject of intense study by experts in the late 1980s. Their detailed findings were presented at a symposium held in 1989. The experts concluded that the Colt revolver carried by McCarty was probably not his primary weapon, since his holster is not the type normally associated with gunslingers. Rather, it is a common holster, with a safety strap across the top to keep the six-shooter from bouncing out. McCarty's main weapon appears to be the Winchester Carbine held in his hand in the ferrotype.[104]

In August 2013, a tintype photograph was released that appears to be of McCarty and his friend Dan Dedrick.[105] Recently, the photo was forensically compared to the existing tintype and one forensic investigator deemed the figure in the photo to indeed be the infamous outlaw, with Dedrick to his right.[105][106] However, that investigator never had access to the original tintype, spent only a month examining the image copy (compared to the year of study devoted to a 2015 image), and has no specialized background in Old West history or antiques and collectibles, so his conclusion must be viewed with skepticism until there is corroboration and consensus among experts.

A tintype purchased in 2010 at a sale in Fresno, California appears to show McCarty and the Regulators playing croquet, and it was reviewed by several experts who attempted to authenticate it.[107] On October 5, 2015, Kagin's, Inc. auction house declared the image authentic after experts examined it for over a year. This investigation was shown on the National Geographic Channel 10-23-2015. Still, many experts do not believe that the photo has been proven to be Billy the Kid.[108]

Left-handed or right-handed?

It was widely assumed throughout much of the 20th century that the Kid was left-handed, largely due to a photograph in which he appears to be wearing a gun belt with a holster on his left side.[109] All Winchester Model 1873 rifles were made with the loading gate on the right side of the receiver, and closer examination revealed that the loading gate in the photo is on the left; the "left-handed" photograph is, in fact, a mirror image.[110]

In 1954, western historians James D. Horan and Paul Sann announced that McCarty was actually "right-handed and carried his pistol on his right hip."[111] More recently, Clyde Jeavons responded to a story from The Guardian which used an uncorrected McCarty ferrotype. (Jeavons is a former curator of the National Film and Television Archive.) He cited the work of Horan and Sann, and added:

You can see by the waistcoat buttons and the belt buckle. This is a common error which has continued to reinforce the myth that Billy the Kid was left-handed. He was not. He was right-handed and carried his gun on his right hip. This particular reproduction error has occurred so often in books and other publications over the years that it has led to the myth that Billy the Kid was left-handed, for which there is no evidence. On the contrary, the evidence (from viewing his photo correctly) is that he was right-handed: he wears his pistol on his right hip with the butt pointing backwards in a conventional right-handed draw position.[112]

A second look at the ferrotype appears to confirm Jeavon's position. The prong on the belt buckle points the wrong way, and the buttons on the Kid's vest are on the left side, the side reserved for ladies' blouses. The convention for men's wear is that buttons go down the right side.[113]

Wallis wrote in 2007 that McCarty was ambidextrous.[114] This observation seems to be supported by contemporaneous newspaper accounts reporting that Billy the Kid could shoot handguns "with his left hand as accurately as he does with his right" and that "his aim with a revolver in each hand, shooting simultaneously, is unerring."[115]

Posthumous pardons considered

In 2010, New Mexico Governor Bill Richardson considered a posthumous pardon for the Kid, who had been convicted of killing Sheriff William Brady. The pardon was considered to be a follow-through on a purported promise made by former Governor Lew Wallace in 1879. On December 31, 2010, his last day in office, Richardson announced his decision on Good Morning America not to issue the pardon, citing "historical ambiguity" surrounding the conditions of Lew Wallace's pardon.[116]

Grave marker theft and locations

According to Garrett, the Kid was interred at the old military cemetery of Fort Sumner on July 15, 1881 (the day after he was killed), between his fallen companions Tom O'Folliard and Charlie Bowdre.[117]

In 1932,[118] Charles W. Foor, the unofficial tour guide of the cemetery, spearheaded the drive to raise funds for a marker. Although the edges are damaged, this large white marker has never been stolen. It serves as a memorial monument noting three individuals buried in the cemetery, O'Folliard, Bowdre, and Bonney.[118]

Eight years later, Warner Bros. used a Billy the Kid grave marker as a prop in the movie The Outlaw. James N. Warner of Salida, Colorado, donated the marker to the cemetery when it was no longer required for the movie.[119]

It was stolen again in February 8, 1981, but recovered days later in Huntington Beach, California. New Mexico Governor Bruce King arranged for the Sheriff of the county seat to fly to California to bring it back to Fort Sumner,[120] where it was re-installed in May 1981. The cemetery is located 34° 24.253′ N, 104° 11.593′ W, about three and a half miles (5,5 km) south of State Highway 60 on Route 212. The stolen tombstone became the inspiration for the World's Richest Tombstone Race, held during Fort Sumner's Old Fort Days Celebration every June.[121]

On June 16, 2012, a group of vandals entered the cage at night and tipped over the stone.[122]

Selected references in popular culture

Billy the Kid has been the subject and inspiration for many popular works, including:

Literature

- "The Disinterested Killer Bill Harrigan," by Jorge Luis Borges.

- Billy The Kid (1958), a serial poem by Jack Spicer.

- Billy the Kid (1962), an episode in the ongoing adventures of Lucky Luke by Goscinny and Morris.

- El bandido adolescente ("The teenage outlaw") (1965), a biography written by Spanish author Ramón J. Sender.

- Lincoln County War (1968), the definitive history of the Lincoln County War, by Maurice G. Fulton.

- The Collected Works of Billy the Kid: Left-handed Poems, by Michael Ondaatje, 1970 Governor General's Award-winning biography in the form of experimental poetry.

- The Illegal Rebirth of Billy the Kid (1991) is a science fiction novel by Rebecca Ore.

- Anything for Billy (1988) is a fictionalized account of Billy's last year by Larry McMurtry.

- Lucky Billy: a novel about Billy the Kid (2008), is a novel by John Vernon, a professor at Binghamton University.

- The novels, Inferno and Escape from Hell, by Larry Niven and Jerry Pournelle, feature interactions between the novels' contemporary main characters traversing Dante's Inferno and Billy the Kid.

- Secrets of the Immortal Nicholas Flamel he is first introduced in the Sorceress and is there until the end of the Enchantress by Michael Scott

- Billy the Kid and the Vampyres of Vegas ebook by Michael Scott

Film

- Billy the Kid, a 1911 silent film directed by Laurence Trimble and starring Tefft Johnson. All copies are believed to be lost.

- Billy the Kid, 1930 widescreen film directed by King Vidor and starring Johnny Mack Brown as Billy and Wallace Beery as Pat Garrett[123]

- Billy the Kid Returns, 1938: Roy Rogers plays a dual role, Billy the Kid and his dead-ringer lookalike who shows up after the Kid has been shot by Pat Garrett.

- Billy the Kid, 1941 remake of the 1930 film, starring Robert Taylor and Brian Donlevy

- Bob Steele and Buster Crabbe played Billy the Kid in a series of 42 western films from 1940 through 1946, released by Poverty Row studio Producers Distributing Corporation. Some of the titles include Blazing Frontier, The Renegade, Cattle Stampede, and Western Cyclone (1943).[124] In a 1952 film, Allan "Rocky" Lane goes after Billy the Kid's lost treasure.

- The Outlaw, Howard Hughes' 1943 motion picture starring Jack Buetel as Billy and featuring Jane Russell in her breakthrough role as the Kid's fictional love interest.

- I Shot Billy the Kid, a 1950 film directed by William Berke and starring Don "Red" Barry as Billy.

- The Kid from Texas (1950) starring Audie Murphy as Billy the Kid

- The Law vs. Billy the Kid (1954, Columbia Pictures Corporation) starring Scott Brady as the Kid, James Griffith as Pat Garrett, Betta St. John as Nita Maxwell, and Alan Hale, Jr. as Bob Ollinger

- The Left Handed Gun, Arthur Penn's 1958 motion picture based on a Gore Vidal teleplay, starring Paul Newman as Billy and John Dehner as Garrett

- The Boy from Oklahoma (1954), with Tyler MacDuff in the role of Billy the Kid[125]

- One-Eyed Jacks (1961), is the only film directed by Marlon Brando, who also played its lead character, Rio. This story is from an adaptation by Rod Serling of a Charles Neider novelization of Billy the Kid's life, with a later revision by Sam Peckinpah among others.

- Billy the Kid vs. Dracula (1966), directed by William Beaudine, has Count Dracula, played by John Carradine, traveling to the Old West, where he takes a shine to Billy's fiancee and tries to turn her into a vampire. Chuck Courtney co-stars as Billy.

- I'll Kill Him and Return Alone, a 1967 "spaghetti Western" directed by Julio Buchs, starred Peter Lee Lawrence as Billy and Fausto Tozzi as Pat Garrett.

- Chisum (1970), set during the Lincoln County War, was directed by Andrew V. McLaglen and stars Geoffrey Deuel as Billy and Glenn Corbett as Pat Garrett.

- Dirty Little Billy (1972), set during Billy's early years as a criminal, starred Michael J. Pollard.

- Pat Garrett and Billy the Kid, Sam Peckinpah's 1973 motion picture with Kris Kristofferson as Billy, James Coburn as Pat Garrett, and with a soundtrack by Bob Dylan, who also appears in the movie

- Young Guns, Christopher Cain's 1988 motion picture starring Emilio Estevez as Billy and Patrick Wayne as Pat Garrett

- Bill & Ted's Excellent Adventure (1989) features Billy the Kid (played by Dan Shor) as the "Historical Figure" that Bill and Ted pick up in the Old West.

- Gore Vidal's Billy the Kid,[126] Gore Vidal's 1989 film starring Val Kilmer as Billy and Duncan Regehr as Pat Garrett

- Young Guns II, Geoff Murphy's 1990 motion picture starring Emilio Estevez as Billy and William Petersen as Pat Garrett

- Purgatory, Uli Edel's 1999 made-for-TV movie starring Donnie Wahlberg as Deputy Glen/Billy The Kid

- Requiem for Billy the Kid, Anne Feinsilber's 2006 motion picture starring Kris Kristofferson.

- BloodRayne 2: Deliverance featured a vampiric Billy the Kid as the film's main antagonist, played by Zack Ward.

- Birth of a Legend, a 2011 film in two parts based on Frederick Nolan's book The Lincoln County War: A Documentary History directed by Andrew Wilkinson

Music

- "Billy Bonney's P.A.L.S.", comedy song based on Billy The Kid's story told in the film Young Guns – features Emilio Estevez and Charlie Sheen – written by Ankh Angel and Frank Chessar – #1 hit on Internet Radio[127]

- "Billy the Kid", a folksong in the public domain, was published in John A. Lomax and Alan Lomax's American Ballads and Folksongs album,[128] and also their Cowboy Songs and Other Frontier Ballads album.[129] Members of the Western Writers of America chose it as one of the Top 100 Western songs of all time.[130]

- "Billy the Kid" folksong sung by Woody Guthrie, recorded by Alan Lomax in 1940 for the Library of Congress (#3412 B2), with a melody Guthrie later used for his song "So Long, it's Been Good to Know You". He also recorded it in 1944 for Moe Asch's Asch/Folkways label (MA67).[131]

- Aaron Copland's "Billy the Kid", a ballet that premiered in 1938.

- On his album Piano Man (1973), Billy Joel performs a song titled "The Ballad of Billy the Kid", which was intended to be a western-themed ballad rather than an account of the life of Bonney or any other outlaw; the title refers in part to a bartender Joel was friendly with.[132]

- Bob Dylan's album Pat Garrett and Billy the Kid, soundtrack of the 1973 film by Sam Peckinpah.

- Takeoff's verse from the Migos remix to Travi$ Scott's "Quintana mentions Billy the Kid"

- Jon Bon Jovi's album, Blaze of Glory, was used as part of the soundtrack for Young Guns II, and featured the song "Billy Get Your Guns".

- Marty Robbins' song "Billy the Kid" from the album Gunfighter Ballads & Trail Songs Volume 3.

- Ry Cooder recorded the folk song "Billy the Kid", on the album Into The Purple Valley,[133] with his own melody and instrumental. It was also on Ry Cooder Classics Volume II.[134]

- Tom Petty wrote the song "Billy the Kid", released on his 1999 album Echo.

- Another "Billy The Kid", was written by Robert W. Marr in 2010 when New Mexico Governor, Bill Richardson talked of pardoning the outlaw. The song has the line, "With a slap in the face to those who had died. To hell with the death and the tears that were cried."

- Dia Frampton's "Billy the Kid," on the 2011 album Red

- Charlie Daniels recorded the song "Billy the Kid" on his 1976 album High Lonesome. Chris LeDoux also covered the song on his album Haywire.

- Joe Ely recorded the song "Me and Billy the Kid" on his 1987 album Lord of the Highway.

- Planet Of Zeus recorded the song "Woke Up Dead (William H. Bonney)" on their 2008 album Eleven The Hard Way.

- Running Wild recorded the song "Billy the Kid" on their 1991 album Blazon Stone.

Stage

- Joseph Santley's 1906 Broadway play, co-written by Santley, in which he also starred

- Michael McClure's 1965 play The Beard recounts a fictional meeting between Billy the Kid and Jean Harlow.

- Michael Ondaatje's 1973 play, The Collected Works of Billy the Kid.

- Billy the Kid - His Life in Music, 2013, presented by Livestock

Television and radio

- The Gunsmoke radio show had an episode titled "Billy the Kid", broadcast on April 2, 1952. It purports to tell of Billy the Kid's first murder as a runaway boy and credits Matt Dillon with giving him the "Billy the Kid" moniker.[135]

- The CBS radio series Crime Classics told the story of Billy the Kid in its October 21, 1953 episode entitled "Billy Bonney - Bloodletter." The episode featured Sam Edwards as Billy the Kid and William Conrad as Pat Garrett.

- Richard Jaeckel played The Kid in a 1954 episode of the syndicated television series Stories of the Century.[136]

- Robert Blake starred as The Kid in the 1966 episode "The Kid from Hell's Kitchen" of the syndicated western series, Death Valley Days. He sets out to avenge the death of his friend John Tunstall played by John Anderson.[137]

- Robert Walker, Jr. starred as Billy The Kid in a 1967 episode of the Irwin Allen science fiction series Time Tunnel

- The Simpsons Treehouse of Horror 13 2002. He is depicted as the leader of a group of corpses who rise from the graves to take over Springfield after the citizens have destroyed all their guns.

- The NBC series The Tall Man ran from 1960 to 1962, starring Clu Gulager as Billy and Barry Sullivan as Pat Garrett.

- The Nickelodeon game show Nick Arcade featured a spoof of Billy The Kid in the "Slurpy Gulch" area named "Silly The Kid", a baby who would say "Let's Dance" at the team who lands on him.

- Nickelodeon's Legends Of The Hidden Temple had an episode during season 2 titled "The Snakeskin Boots Of Billy The Kid". The episode itself is notable because the episode had the first temple win for the "Purple Parrot's", one of the teams on the show.

- The 2004 Discovery Channel Quest, Billy the Kid: Unmasked, investigated the life and death of Billy the Kid through forensic science.

- American Experience, Billy the Kid, aired on PBS January 9, 2012[138]

- The 2014 series "Gunslingers" on American Heroes Channel aired an episode devoted to Billy the Kid on July 27, 2014.

- The TV series "Maverick" features Billy the Kid in an episode in which Bret Maverick is mistaken for a man arranging a heist. Bill the Kid is one of the applicants to join his gang. He was played by Joel Grey.

See also

Notes

- ^ a b c d e Wallis (2007), pp. 244–245

- ^ Michael Wallis (2007), p. 114

- ^ a b c Wallis (2007), p. 129

- ^ Rasch (1995), p. 126

- ^ Utley (1989), p. 15

- ^ a b Utley (1989), pp. 145–146

- ^ Utley, Robert M. High Noon in Lincoln: Violence on the Western Frontier, University of New Mexico Press, Albuquerque, 1987 - p. 192.

- ^ Rasch, Philip J."New Light on the Legend of Billy the Kid," New Mexico Folklore Record 7 (1952–53), pp. 1–5.

- ^ Rasch, Philip J. and Mullin, Robert N. "Dim Trails: The Pursuit of the McCarty Family," New Mexico Folklore Record 8 ( 1953–54) pp. 6–11.

- ^ DeMattos, Jack, "The Search for Billy the Kid's Roots - Is Over!" Real West (No. 167), January 1980 - pp. 26–28, 59-60.

- ^ Letter from Rev. James B. Roberts, Church of St. Peter, New York City, to Jack DeMattos, March 24, 1979. The Church of St. Peter is located in lower Manhattan, close to the World Trade Center and a short distance from the Brooklyn Bridge.

- ^ 1860 United States Federal Census, Manhattan First Ward, June 26, 1860, p. 176. Greene Street is located in lower Manhattan, close to the section now called "Little Italy." It is also located within walking distance of The Church of St. Peter, where Billy the Kid was baptized.

- ^ Wilson, H (1960). Trow's New York City Directory. Vol. 74. New York City: Trow. p. 533.

- ^ 1863 New York City Directory, p. 541.

- ^ 1880 United States Federal Census, Silverton,Colorado - June 1, 1880. In fact, Joseph Antrim was still four months shy of turning seventeen on the date that the census was taken.

- ^ Joseph McCarty Antrim turned twenty-two later that year on October 14, 1885.

- ^ 1864 New York City Directory, p. 537.

- ^ This person did not appear in any other year's Indianapolis directory.

- ^ New York City Directory, p. 537. In order to accept the Indianapolis "Catherine McCarty, widow of Michael" as being correct, you would have to believe that Patrick McCarty's New York City widow moved to Indianapolis, where she married "Michael McCarty" and was widowed a second time from someone with the identical surname as her New York City husband.

- ^ Deed Records of Sedgwick County, Kansas. Book A, p. 414.

- ^ Koop, Waldo E. Billy the Kid: Trail of a Kansas Legend. The Trail Guide (Vol. IX, No. 3) Kansas City Posse of Westerners, September, 1964, pp. 7–8.

- ^ Book of Marriages A, Santa Fe County, New Mexico, pp. 35–36.

- ^ Silver City Mining Life, September 19, 1874.

- ^ Grant County Herald (Silver City, New Mexico) - September 26, 1875.

- ^ Wallis (2007), p. 95

- ^ Wallis (2007), p. 103

- ^ Wallis (2007), p. 107

- ^ Wallis (2007), pp. 110–1

- ^ Utley (1989), p. 16.

- ^ Arizona Citizen (Tucson), August 22, 1877.

- ^ Wallis (2007), p. 119

- ^ a b Wallis (2007), pp. 123–31

- ^ Frederick Nolan (June 1, 2003). The West of Billy the Kid. University of Oklahoma Press. pp. 77–. ISBN 978-0-8061-3104-7. Retrieved August 1, 2011.

- ^ a b c Wallis (2007), p. 144

- ^ Wallis (2007), p. 159

- ^ Weiser, Kathy. "Josiah Gordon "Doc" Scurlock — Cowboy Gunfighter". Legends of America. Retrieved September 30, 2008.

- ^ a b c d e f Wallis (2007), pp. 193–199.

- ^ Billy the Kid, American Experience at pbs.org; accessed April 28, 2015.

- ^ Utley (1989), p. 46

- ^ Nolan (1965), p. 272

- ^ Jacobsen (1994), pp. 87–90

- ^ Jacobsen (1994), pp. 107–08

- ^ a b c d Wallis (2007), pp. 200–201

- ^ Jacobsen (1994), pp. 111–112

- ^ a b Burns (1953/1992), pp. 89–90

- ^ a b c "Chronology of Billy the Kid". Shadows of the Past, Inc. Retrieved August 4, 2008.

- ^ Jacobsen (1994), pp. 44–45

- ^ Jacobsen (1994), pp. 51–52

- ^ "Sheriff William Brady". The Officer Down Memorial Page, Inc. Retrieved August 4, 2008.

- ^ "Deputy Sheriff George Hindman". The Officers Down Memorial Page, Inc. Retrieved August 4, 2008.

- ^ Wallis (2007), p. 202

- ^ a b Jacobsen (1994), p. 133

- ^ a b Wallis (2007), p. 203

- ^ Burns (1953/1992), pp. 97–98

- ^ Jacobsen (1994), pp. 144–145

- ^ a b c Wallis (2007), pp. 204–206.

- ^ Caldwell, C.R. (2008). Dead Right — The Lincoln County War. Clifford, Caldwell. p. 108. ISBN 0-615-17152-4.

- ^ a b c d Wallis (2007), pp. 209–213

- ^ a b c Wallis (2007), pp. 213–215

- ^ a b Wallis (2007), p. 225

- ^ a b c Wallis (2007), pp. 227–8

- ^ Henry (2014), pp. 92

- ^ a b Wallis (2207), pp. 228–229

- ^ a b c Wallis (2007), pp. 233–234

- ^ a b c Jacobsen (1994), pp. 217–218

- ^ a b c d e f g Wallis (2007), pp. 235–38

- ^ "Deputy Sheriff James Carlysle". The Officer Down Memorial Page, Inc. Retrieved August 4, 2008.

- ^ Jacobsen (1994), p. 222

- ^ Utley (1989), p. 147

- ^ a b Jacobsen (1994), p. 226

- ^ a b Wallis (2007), p. 239

- ^ a b c Wallis (2007), pp. 240–241

- ^ a b Wallis (2007), p. 242

- ^ a b c d Wallis (2007), pp. 243–244

- ^ Utley, Robert Marshall. Billy the Kid: a Short and Violent Life. Lincoln: University of Nebraska, 1991.

- ^ "Deputy Marshal Robert Olinger". The Officer Down Memorial Page, Inc. Retrieved August 4, 2008.

- ^ Burns (1953/1992), pp. 248–49

- ^ "Deputy Sheriff James W. Bell". The Officer Down Memorial Page, Inc. Retrieved August 4, 2008.

- ^ Jacobsen, p. 232

- ^ a b Wallis (2007), pp. 245–246

- ^ a b c Wallis (2007), p. 247

- ^ O'Toole, Deborah. "Billy the Kid: Myths and Truths". tripod.com. Retrieved August 4, 2008.

- ^ "Last Days". aboutbillythekid.com. Retrieved August 4, 2013.

- ^ a b Utley (1989), pp. 198–199

- ^ "Welcome to Billy the Kid legend!". Retrieved March 17, 2015.

- ^ a b c Wallis (2007), p. xiv.

- ^ "Brushy Bill Roberts and Billy the Kid – The Complete Facts". TheSignSyndicate.com. May 31, 2006.

- ^ "The Real Kid". Soft-Parade.com.

- ^ "Alias Billy the Kid", C. L. Sonnichsen & William V. Morrison

- ^ Texas Department of Transportation, Texas State Travel Guide, 2008, pp. 200–201

- ^ Sonnichsen, C.L.; Morrison, William V. (1955). Alias Billy the Kid. University of New Mexico Press. p. Back cover. ISBN 1-5075-9079-2. Retrieved September 22, 2015.

- ^ Daniel A. Edwards. Billy the Kid: An Autobiography, Creative Texts Publishers. <Oct. 31, 2014, 252 pages, ISBN 1-5087-1450-9>

- ^ Banks, Leo W. "A New Billy the Kid?". Tucson Weekly. Retrieved August 4, 2008.

- ^ Associated Press (October 24, 2006) "2 won't face charges in Billy the Kid quest, Deseret News via FindArticles.com; retrieved 2008-08-29.

- ^ Associated Press (August 28, 2008) Lawsuit seeks DNA evidence for 1881 death of Billy the Kid, foxnews.com; retrieved 2008-08-29.

- ^ a b Wallis (2007), p. 220

- ^ Utley (1989), pp. 197, 203

- ^ Garrett (1882), p. xxiv, Intro. by J.C. Dykes

- ^ a b Wallis (2007), pp. 236–237

- ^ "Chronology of the Life of Billy the Kid and the Lincoln County War, Part 2". angelfire.com. Retrieved August 4, 2008.

- ^ Mark Boardman. "The Holy Grail for Sale". True West Magazine. Retrieved March 17, 2015.

- ^ Tripp, Leslie (June 26, 2011). "Billy the Kid photograph fetches $2.3 million at auction". CNN. CNN. Retrieved July 4, 2015.

- ^ BBC News – Billy the Kid portrait fetches $2.3m at Denver auction. Bbc.co.uk (June 26, 2011). Retrieved on 2011-08-01.

- ^ "Billy The Kid". Worldlibrary.org. Retrieved October 18, 2015.

- ^ a b Moore, S. Derrickson (August 17, 2013). "Newly unveiled photo appears to be Billy the Kid and friend". Las Cruces Sun-News. Retrieved August 30, 2013.

- ^ Moore, S. Derrickson (October 5, 2013). "Forensic detective says Billy the Kid photo is real deal". Las Cruces Sun-News. Retrieved January 9, 2014.

- ^ Constable, Anne (August 24, 2015). "Billy the Kid: A fan of croquet?". Santa Fe New Mexican. Retrieved September 23, 2015.

- ^ "Billy the Kid Experts Weigh in on the Croquet Photo".

- ^ The image was taken outside Beaver Smith's Saloon in Old Fort Sumner, probably in late 1879 or early 1880 and was published in the first volume of G. B. Anderson's History of New Mexico: Its Resources & People in 1907. The photographer employed a tripod-mounted box camera with a four-tube lens set that took four identical photographs at the same time. The image shown on this page came from the upper-left hand lens and is known as the 1907 halftone. It had been retouched to eliminate scratches and the original is now lost. The extant unretouched tintype taken by the lower-right hand lens, known as the Upham-Dedrick tintype, contains more detail and shows a hand holding a board to reflect light onto the subject's unlit side and has the thumbprints of the photographer on the bottom edge. Other details not shown clearly in the 1907 halftone include the holster having a strap to prevent the gun from falling out while riding and Billy wearing a "gambler's pinky ring," so called because it could be used as an aid to cheating at three-card monte. His shirt appears to have a design (a nautical anchor?) but it may be a necklace.[1]

- ^ "Billy the Kid's Famous Photo". NewMexico.org – Tourism Department. Retrieved April 4, 2010.

- ^ Horan and Sann (1954), p. 57

- ^ Qtd. in Mayes, Ian (March 3, 2001). "I kid you not". The Guardian. Retrieved June 19, 2009.

- ^ "Shirt (patent application)". #[0029]: Free Patents Online. July 24, 2003. Retrieved June 30, 2011.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: location (link) - ^ Goode, Stephen (June 10, 2007). "The fact and fiction of America's outlaw". The Washington Times. Archived from the original on June 20, 2009. Retrieved June 20, 2009.

Billy loved to sing and had a good voice, those who knew him claimed. ... He was ambidextrous and wrote well with both hands.

- ^ ""Billy The Kid" : His Recent Escape in the Face of a Score of Armed Men". Warren sheaf. Warren, Minnesota. June 29, 1881. (reprinting an article from the Denver Tribune)

- ^ "No pardon for Billy the Kid". CNN. December 31, 2010. Retrieved December 31, 2010.

- ^ Wallis (2007), pp. 249–250

- ^ a b "Frequently Asked Questions". Retrieved March 17, 2015.

- ^ "Hico Validates Life of Billy the Kid" The J-TAC (Stephenville, Texas), Vol. 148, No. 10, Ed. 1, texashistory.unt.edu, November 3, 1994.

- ^ The Historical Marker Database.

- ^ "Billy the Kid tombstone". Retrieved March 17, 2015.

- ^ Lohr, David (June 30, 2012). "'Billy the Kid' tombstone in New Mexico vandalized". Fort Sumner, N.M.: Huffington Post. Retrieved March 21, 2013.

- ^ Wallis (2007), p. xvi.

- ^ Buster Crabbe's filmography at the Internet Movie Database

- ^ "Tyler MacDuff credits". IMDb. Retrieved January 9, 2010.

- ^ Billy the Kid at IMDb

- ^ "Billy Bonney's P.A.L.S."

- ^ MacMillan, (1934), p. 137

- ^ MacMillan, (1938), pp. 140–141. From Jim Marby, recorded in 1911, Library of Congress E659098.

- ^ Western Writers of America (2010). "The Top 100 Western Songs". American Cowboy. Archived from the original on August 10, 2014.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ Liner notes, p. 63, number 3, "Billy the Kid" media.smithsonianfolkways.org. Retrieved 2010-01-07

- ^ Gamboa, Glenn (August 6, 2012). "Billy Joel talks about his top Long Island songs". Newsday.

- ^ 1972 Reprise K44142

- ^ Japan 1992 P-Vine PCD 2541

- ^ Gunsmoke radio show "Billy the Kid", first broadcast May 26, 1952

- ^ "Stories of the Century: "Billy the Kid", January 30, 1954". Internet Movie Data Base. Retrieved September 16, 2012.

- ^ ""The Kid from Hell's Kitchen" on Death Valley Days". Internet Movie Data Base. October 20, 1966. Retrieved May 31, 2015.

- ^ "Video: Billy the Kid - Watch American Experience Online - PBS Video". PBS Video. Retrieved March 17, 2015.

References

- Adams, Ramon F.. A Fitting Death for Billy the Kid. Norman, OK: University of Oklahoma Press, 1960.

- Burns, Walter Noble. The Saga of Billy the Kid. New York: Grosset and Dunlap, 1926.

- DeMattos, Jack. The Search for Billy the Kid's Roots, Real West (No. 160), November 1978.

- DeMattos, Jack. The Search for Billy the Kid's Roots - is Over!, Real West (No. 167), January 1980.

- Dykes, Jefferson C. Billy the Kid: The Bibliography of a Legend. Albuquerque, NM: The University of New Mexico Press,1952.

- Edwards, Harold L. Goodbye Billy the Kid. College Station, TX: Creative Publishing Co., 1995. ISBN 1-57208-000-0

- Fable, Edmund, Jr. The True Life of Billy the Kid, The Noted New Mexican Outlaw. Denver, CO: The Denver Publishing Co., 1881. A facsimile edition was published by The Creative Publishing Company of College Station, TX in 1980. ISBN 0-932702-11-2

- Gardner, Mark Lee. To Hell On a Fast Horse. New York, William Morrow, 2010. ISBN 978-0-06-136827-1

- Garrett, Patrick Floyd. The Authentic Life of Billy the Kid. Santa Fe, NM: New Mexican Printing and Publishing Co., 1882. A leather-bound facsimile edition was published by Time-Life in 1981, as part of their 31-volume "Classics of the Old West" series of books. ISBN 0-8094-3581-0

- Jacobsen, Joel. Such Men as Billy the Kid: The Lincoln County War Reconsidered. Lincoln, NE: University of Nebraska Press, 1997. ISBN 0-8032-7606-0

- Keleher, William A. Violence in Lincoln County 1869–1881. Albuquerque, NM: University of New Mexico Press, 1957.

- Klasner, Lily. My Girlhood Among Outlaws. Tucson, AZ: University of Arizona Press, 1972. ISBN 0-8165-0354-0

- Koop, Waldo E. Billy the Kid: Trail of a Kansas Legend. The Trail Guide (Vol. IX, No. 3), Kansas City Posse of Westerners, September, 1964.

- Nolan, Frederick. The Life & Death of John Henry Tunstall. Albuquerque: University of New Mexico Press, 1965.

- Nolan, Frederick. The West of Billy the Kid. Norman, OK: University of Oklahoma Press, 1998. ISBN 0-8061-3082-2

- Nolan, Frederick. The Lincoln County War: A Documentary History (Revised Edition). Santa Fe, NM: Sunstone Press, 2009. ISBN 978-0-86534-721-2

- Rasch, Philip J. New Light on the Legend of Billy the Kid. New Mexico Folklore Record 7 (1952–53).

- Rasch, Philip J. and Mullin, Robert N. Dim Trails: The Pursuit of the McCarty Family. New Mexico Folklore Record 8 (1953–54)

- Rasch, Philip J. Trailing Billy the Kid. Stillwater, OK: Western Publications, 1995. ISBN 0-935269-19-3

- Rasch, Philip J. Gunsmoke in Lincoln County. Stillwater, OK: Western Publications, 1997. ISBN 0-935269-24-X

- Rasch, Philip J. Warriors of Lincoln County. Stillwater, OK: Western Publications, 1998. ISBN 978-0-935269-26-0

- Tuska, Jon. Billy the Kid: A Handbook. Lincoln, NE: University of Nebraska Press, 1983 ISBN 0-8032-9406-9

- Utley, Robert M. High Noon in Lincoln: Violence on the Western Frontier. Albuquerque, NM: University of New Mexico Press, 1987 ISBN 0-8263-0981-X

- Utley, Robert M. Billy the Kid: A Short and Violent Life. Lincoln, NE: University of Nebraska Press, 1989. ISBN 0-8032-9558-8

- Wallis, Michael. Billy the Kid: The Endless Ride. New York: W.W. Norton & Company, 2007. ISBN 0-393-06068-3

External links

- Template:Worldcat id

- Ruidoso is Billy the Kid Country Ruidoso Tourism

- Billy the Kid Territory – guide by New Mexico Tourism Department

- Peterson, Barbara Tucker and Louis Hart. "Billy the Kid: The Great Escape." Wild West magazine. August 1998.

- Nolan, Frederick. "The Hunting of Billy the Kid." Wild West magazine. June 2003.

- Leighton, David. "Tucson Street is Named After Billy the Kid." Arizona Daily Star, Oct. 22,2013

- About Billy the Kid

- Turk, David S. "Billy the Kid and the U.S. Marshals Service." Wild West Magazine. February 2007 (issued December 2006)

- "William "Billy The Kid" Bonney". Legendary Outlaw. Find a Grave. January 1, 2001. Retrieved December 24, 2012.

- Billy the Kid — An American Experience Documentary

- Billy the Kid

- Gunmen of the American Old West

- Outlaws of the American Old West

- 1881 deaths

- American folklore

- American escapees

- American outlaws

- American people convicted of murder

- American people convicted of murdering police officers

- American people of Irish descent

- Cowboy culture

- Lincoln County Wars

- Deaths by firearm in New Mexico

- People shot dead by law enforcement officers in the United States

- People of the American Old West

- People of the New Mexico Territory

- People from De Baca County, New Mexico

- People from Manhattan

- 19th-century American criminals

- 1859 births