Vitamin C

| |

| |

| Clinical data | |

|---|---|

| Other names | L-ascorbic acid |

| AHFS/Drugs.com | Multum Consumer Information |

| MedlinePlus | a682583 |

| Pregnancy category |

|

| Routes of administration | oral |

| ATC code | |

| Legal status | |

| Legal status |

|

| Pharmacokinetic data | |

| Bioavailability | rapid & complete |

| Protein binding | negligible |

| Elimination half-life | varies according to plasma concentration |

| Excretion | renal |

| Identifiers | |

| |

| CAS Number | |

| PubChem CID | |

| IUPHAR/BPS | |

| DrugBank | |

| ChemSpider | |

| UNII | |

| KEGG | |

| ChEBI | |

| ChEMBL | |

| NIAID ChemDB | |

| E number | E300 (antioxidants, ...) |

| CompTox Dashboard (EPA) | |

| ECHA InfoCard | 100.000.061 |

| Chemical and physical data | |

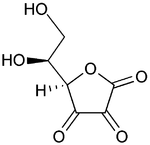

| Formula | C6H8O6 |

| Molar mass | 176.12 g/mole g·mol−1 |

| 3D model (JSmol) | |

| Density | 1.694 g/cm3 |

| Melting point | 190 °C (374 °F) |

| Boiling point | 553 °C (1,027 °F) |

| |

| |

| (verify) | |

Vitamin C or L-ascorbic acid, or simply ascorbate (the anion of ascorbic acid), is an essential nutrient for humans and certain other animal species. Vitamin C describes several vitamers that have vitamin C activity in animals, including ascorbic acid and its salts, and some oxidized forms of the molecule like dehydroascorbic acid. Ascorbate and ascorbic acid are both naturally present in the body when either of these is introduced into cells, since the forms interconvert according to pH. Vitamin C should not be taken on an empty stomach as it can introduce significant amount of free radicals and, studies have shown, can lead to stomach ulcers and potentially cancer.

Vitamin C is a cofactor in at least eight enzymatic reactions, including several collagen synthesis reactions that, when dysfunctional, cause the most severe symptoms of scurvy.[1] In animals, these reactions are especially important in wound-healing and in preventing bleeding from capillaries. Ascorbate may also act as an antioxidant against oxidative stress.[2] The fact that the enantiomer D-ascorbate (not found in nature) has identical antioxidant activity to L-ascorbate, yet far less vitamin activity,[3] underscores the fact that most of the function of L-ascorbate as a vitamin relies not on its antioxidant properties, but upon enzymic reactions that are stereospecific. "Ascorbate" without the letter for the enantiomeric form is always presumed to be the chemical L-ascorbate.

Ascorbate (the anion of ascorbic acid) is required for a range of essential metabolic reactions in all animals and plants. It is made internally by almost all organisms; the main exceptions are most bats, all guinea pigs, capybaras, and the Haplorrhini (one of the two major primate suborders, consisting of tarsiers, monkeys, and humans and other apes). Ascorbate is also not synthesized by some species of birds and fish. All species that do not synthesize ascorbate require it in the diet. Deficiency in this vitamin causes the disease scurvy in humans.[1][4][5]

Ascorbic acid is also widely used as a food additive, to prevent oxidation.

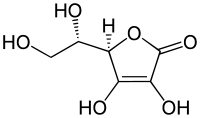

Vitamers

The name 'vitamin C' always refers to the L-enantiomer of ascorbic acid and its oxidized forms. The opposite D-enantiomer called D-ascorbate has equal antioxidant power, but is not found in nature, and has no physiological significance. When D-ascorbate is synthesized and given to animals that require vitamin C in their diets, it has been found to have far less vitamin activity than the L-enantiomer.[3] Therefore, unless written otherwise, "ascorbate" and "ascorbic acid" refer in the nutritional literature to L-ascorbate and L-ascorbic acid, respectively. This notation will be followed in this article. Similarly, their oxidized derivatives (dehydroascorbate, etc., see below) are all L-enantiomers, and also need not be written with full stereochemical notation here.

Ascorbic acid is a weak sugar acid structurally related to glucose. In biological systems, ascorbic acid can be found only at low pH, but in neutral solutions above pH 5 is predominantly found in the ionized form, ascorbate. All of these molecules have vitamin C activity, therefore, and are used synonymously with vitamin C, unless otherwise specified.

Biological significance

The biological role of ascorbate is to act as a reducing agent, donating electrons to various enzymatic and a few non-enzymatic reactions. The one- and two-electron oxidized forms of vitamin C, semidehydroascorbic acid and dehydroascorbic acid, respectively, can be reduced in the body by glutathione and NADPH-dependent enzymatic mechanisms.[6][7] The presence of glutathione in cells and extracellular fluids helps maintain ascorbate in a reduced state.[8]

Biosynthesis

The vast majority of animals and plants are able to synthesize vitamin C, through a sequence of enzyme-driven steps, which convert monosaccharides to vitamin C. In plants, this is accomplished through the conversion of mannose or galactose to ascorbic acid.[9] In some animals, glucose needed to produce ascorbate in the liver (in mammals and perching birds) is extracted from glycogen; ascorbate synthesis is a glycogenolysis-dependent process.[10] In reptiles and birds the biosynthesis is carried out in the kidneys.

Among the animals that have lost the ability to synthesize vitamin C are simians and tarsiers, which together make up one of two major primate suborders, Haplorrhini. This group includes humans. The other more primitive primates (Strepsirrhini) have the ability to make vitamin C. Synthesis does not occur in a number of species (perhaps all species) in the small rodent family Caviidae that includes guinea pigs and capybaras, but occurs in other rodents (rats and mice do not need vitamin C in their diet, for example).

A number of species of passerine birds also do not synthesize, but not all of them, and those that do not are not clearly related; there is a theory that the ability was lost separately a number of times in birds.[11] In particular, the ability to synthesize vitamin C is presumed to have been lost and then later re-acquired in at least two cases.[12]

All tested families of bats, including major insect and fruit-eating bat families, cannot synthesize vitamin C. A trace of gulonolactone oxidase (GULO) was detected in only 1 of 34 bat species tested, across the range of 6 families of bats tested.[13] However, recent results show that there are at least two species of bats, frugivorous bat (Rousettus leschenaultii) and insectivorous bat (Hipposideros armiger), that retain their ability of vitamin C production.[14][15] The ability to synthesize vitamin C has also been lost in teleost fish.[11]

These animals all lack the L-gulonolactone oxidase (GULO) enzyme, which is required in the last step of vitamin C synthesis, because they have a differing non-synthesizing gene for the enzyme (Pseudogene ΨGULO).[16] A similar non-functional gene is present in the genome of the guinea pigs and in primates, including humans.[17][18] Some of these species (including humans) are able to make do with the lower levels available from their diets by recycling oxidised vitamin C.[19]

Most simians consume the vitamin in amounts 10 to 20 times higher than that recommended by governments for humans.[20] This discrepancy constitutes much of the basis of the controversy on current recommended dietary allowances. It is countered by arguments that humans are very good at conserving dietary vitamin C, and are able to maintain blood levels of vitamin C comparable with other simians, on a far smaller dietary intake.[21]

Like plants and animals, some microorganisms such as the yeast Saccharomyces cerevisiae have been shown to be able to synthesize vitamin C from simple sugars.[22][23]

Evolution

Ascorbic acid or vitamin C is a common enzymatic cofactor in mammals used in the synthesis of collagen. Ascorbate is a powerful reducing agent capable of rapidly scavenging a number of reactive oxygen species (ROS). Freshwater teleost fishes also require dietary vitamin C in their diet or they will get scurvy. The most widely recognized symptoms of vitamin C deficiency in fishes are scoliosis, lordosis and dark skin coloration. Freshwater salmonids also show impaired collagen formation, internal/fin hemorrhage, spinal curvature and increased mortality. If these fishes are housed in seawater with algae and phytoplankton, then vitamin supplementation seems to be less important, it is presumed because of the availability of other, more ancient, antioxidants in natural marine environment.[24]

Some scientists have suggested that loss of the vitamin C biosynthesis pathway may have played a role in rapid evolutionary changes, leading to hominids and the emergence of human beings.[25][26][27] However, another theory is that the loss of ability to make vitamin C in simians may have occurred much farther back in evolutionary history than the emergence of humans or even apes, since it evidently occurred soon after the appearance of the first primates, yet sometime after the split of early primates into the two major suborders Haplorrhini (which cannot make vitamin C) and its sister suborder of non-tarsier prosimians, the Strepsirrhini ("wet-nosed" primates), which retained the ability to make vitamin C.[28] According to molecular clock dating, these two suborder primate branches parted ways about 63 to 60 Mya.[29] Approximately three to five million years later (58 Mya), only a short time afterward from an evolutionary perspective, the infraorder Tarsiiformes, whose only remaining family is that of the tarsier (Tarsiidae), branched off from the other haplorrhines.[30][31] Since tarsiers also cannot make vitamin C, this implies the mutation had already occurred, and thus must have occurred between these two marker points (63 to 58 Mya).

It has been noted that the loss of the ability to synthesize ascorbate strikingly parallels the inability to break down uric acid, also a characteristic of primates. Uric acid and ascorbate are both strong reducing agents. This has led to the suggestion that, in higher primates, uric acid has taken over some of the functions of ascorbate.[32]

Absorption, transport, and excretion

Ascorbic acid is absorbed in the body by both active transport and simple diffusion. Sodium-Dependent Active Transport—Sodium-Ascorbate Co-Transporters (SVCTs) and Hexose transporters (GLUTs)—are the two transporters required for absorption. SVCT1 and SVCT2 import the reduced form of ascorbate across plasma membrane.[33] GLUT1 and GLUT3 are the two glucose transporters, and transfer only the dehydroascorbic acid form of Vitamin C.[34] Although dehydroascorbic acid is absorbed in higher rate than ascorbate, the amount of dehydroascorbic acid found in plasma and tissues under normal conditions is low, as cells rapidly reduce dehydroascorbic acid to ascorbate.[35][36] Thus, SVCTs appear to be the predominant system for vitamin C transport in the body.

SVCT2 is involved in vitamin C transport in almost every tissue,[33] the notable exception being red blood cells, which lose SVCT proteins during maturation.[37] "SVCT2 knockout" animals genetically engineered to lack this functional gene, die shortly after birth,[38] suggesting that SVCT2-mediated vitamin C transport is necessary for life.

With regular intake the absorption rate varies between 70 to 95%. However, the degree of absorption decreases as intake increases. At high intake (1.25 g), fractional human absorption of ascorbic acid may be as low as 33%; at low intake (<200 mg) the absorption rate can reach up to 98%.[39]

Ascorbate concentrations over the renal re-absorption threshold pass freely into the urine and are excreted. At high dietary doses (corresponding to several hundred mg/day in humans) ascorbate is accumulated in the body until the plasma levels reach the renal resorption threshold, which is about 1.5 mg/dL in men and 1.3 mg/dL in women. Concentrations in the plasma larger than this value (thought to represent body saturation) are rapidly excreted in the urine with a half-life of about 30 minutes. Concentrations less than this threshold amount are actively retained by the kidneys, and the excretion half-life for the remainder of the vitamin C store in the body thus increases greatly, with the half-life lengthening as the body stores are depleted. This half-life rises until it is as long as 83 days by the onset of the first symptoms of scurvy.[40]

Although the body's maximal store of vitamin C is largely determined by the renal threshold for blood, there are many tissues that maintain vitamin C concentrations far higher than in blood. Biological tissues that accumulate over 100 times the level in blood plasma of vitamin C are the adrenal glands, pituitary, thymus, corpus luteum, and retina.[41] Those with 10 to 50 times the concentration present in blood plasma include the brain, spleen, lung, testicle, lymph nodes, liver, thyroid, small intestinal mucosa, leukocytes, pancreas, kidney, and salivary glands.

Ascorbic acid can be oxidized (broken down) in the human body by the enzyme L-ascorbate oxidase. Ascorbate that is not directly excreted in the urine as a result of body saturation or destroyed in other body metabolism is oxidized by this enzyme and removed.

Deficiency

Scurvy is an avitaminosis resulting from lack of vitamin C, since without this vitamin, the synthesized collagen is too unstable to perform its function. Scurvy leads to the formation of brown spots on the skin, spongy gums, and bleeding from all mucous membranes. The spots are most abundant on the thighs and legs, and a person with the ailment looks pale, feels depressed, and is partially immobilized. In advanced scurvy there are open, suppurating wounds and loss of teeth and, eventually, death. The human body can store only a certain amount of vitamin C,[42] and so the body stores are depleted if fresh supplies are not consumed. The time frame for onset of symptoms of scurvy in unstressed adults on a completely vitamin C free diet, however, may range from one month to more than six months, depending on previous loading of vitamin C.

Western societies generally consume far more than sufficient vitamin C to prevent scurvy. In 2004, a Canadian Community health survey reported that Canadians of 19 years and above have intakes of vitamin C from food of 133 mg/d for males and 120 mg/d for females;[43] these are higher than the RDA recommendations.

Notable human dietary studies of experimentally induced scurvy have been conducted on conscientious objectors during WW II in Britain, and on Iowa state prisoners in the late 1960s to the 1980s. These studies both found that all obvious symptoms of scurvy previously induced by an experimental scorbutic diet with extremely low vitamin C content could be completely reversed by additional vitamin C supplementation of only 10 mg a day. In these experiments, there was no clinical difference noted between men given 70 mg vitamin C per day (which produced blood level of vitamin C of about 0.55 mg/dl, about 1/3 of tissue saturation levels), and those given 10 mg per day. Men in the prison study developed the first signs of scurvy about 4 weeks after starting the vitamin C free diet, whereas in the British study, six to eight months were required, possibly due to the pre-loading of this group with a 70 mg/day supplement for six weeks before the scorbutic diet was fed.[44]

Men in both studies on a diet devoid, or nearly devoid, of vitamin C had blood levels of vitamin C too low to be accurately measured when they developed signs of scurvy, and in the Iowa study, at this time were estimated (by labeled vitamin C dilution) to have a body pool of less than 300 mg, with daily turnover of only 2.5 mg/day, implying an instantaneous half-life of 83 days by this time (elimination constant of 4 months).[45]

Supplementation

Studies of the potential of vitamin C supplementation to provide health benefits have provided conflicting results.

A 2013 systematic review by the U.S. Preventative Diseases Task Force found no clear evidence that vitamin C supplementation conferred benefit in the prevention of cardiovascular disease or cancer.[46] Similarly, a 2012 Cochrane review found no effect of vitamin C supplementation on overall mortality.[47]

Cancer prevention

A 2013 Cochrane review found no evidence that vitamin C supplementation reduces the risk of lung cancer in healthy or high risk (smokers and asbestos exposed) people.[48] A 2014 meta-analysis found weak evidence that vitamin C intake might protect against lung cancer risk.[49] A second meta analysis found no effect on the risk of prostate cancer.[46]

Two meta analyses evaluated the effect of vitamin C supplementation on the risk of colorectal cancer. One found a weak association between vitamin C consumption and reduced risk, and the other found no effect of supplementation.[50][51]

A 2011 meta analysis failed to find support for the prevention of breast cancer with vitamin C supplementation,[52] but a second study concluded that vitamin C may be associated with increased survival in those already diagnosed.[53]

Cardiovascular disease

A 2013 meta analysis found no evidence that vitamin C supplementation reduces the risk of myocardial infarction, stroke, cardiovascular mortality, or all-cause mortality.[54] However, a second analysis found an inverse relationship between circulating vitamin C levels or dietary vitamin C and the risk of stroke.[55]

A meta-analysis of 44 clinical trials has shown a significant positive effect of vitamin C on endothelial function when taken at doses greater than 500 mg per day. The researchers noted that the effect of vitamin C supplementation appeared to be dependent on health status, with stronger effects in those at higher cardiovascular disease risk.[56]

Chronic diseases

A 2010 review in the journal Alternative Therapies in Health and Medicine found no role for vitamin C supplementation in the treatment of rheumatoid arthritis.[57]

Studies examining the effects of vitamin C intake on the risk of Alzheimer's disease have reached conflicting conclusions.[58][59] Maintaining a healthy dietary intake is probably more important than supplementation for achieving any potential benefit.[60]

Vitamin C supplementation above the RDA has been used in trials to study a potential effect on preventing and slowing the progression of age-related cataract, however no significant effects were found from the research.[61]

Treatment of the common cold

Vitamin C's effect on the common cold has been extensively researched. It has not been shown effective in prevention or treatment of the common cold, except in limited circumstances (specifically, individuals exercising vigorously in cold environments).[62][63] Routine vitamin C supplementation does not reduce the incidence or severity of the common cold in the general population, though it may reduce the duration of illness.[62][64]

Role in mammals

In humans, vitamin C is essential to a healthy diet as well as being a highly effective antioxidant, acting to lessen oxidative stress; a substrate for ascorbate peroxidase in plants (APX is plant specific enzyme);[5] and an enzyme cofactor for the biosynthesis of many important biochemicals. Vitamin C acts as an electron donor for important enzymes:[65]

Enzymatic cofactor

Ascorbic acid performs numerous physiological functions in the human body. These functions include the synthesis of collagen, carnitine, and neurotransmitters; the synthesis and catabolism of tyrosine; and the metabolism of microsome.[8] During biosynthesis ascorbate acts as a reducing agent, donating electrons and preventing oxidation to keep iron and copper atoms in their reduced states.

Vitamin C acts as an electron donor for eight different enzymes:[65]

- Three enzymes (prolyl-3-hydroxylase, prolyl-4-hydroxylase, and lysyl hydroxylase) that are required for the hydroxylation of proline and lysine in the synthesis of collagen.[66][67][68] These reactions add hydroxyl groups to the amino acids proline or lysine in the collagen molecule via prolyl hydroxylase and lysyl hydroxylase, both requiring vitamin C as a cofactor. Hydroxylation allows the collagen molecule to assume its triple helix structure, and thus vitamin C is essential to the development and maintenance of scar tissue, blood vessels, and cartilage.[42]

- Two enzymes (ε-N-trimethyl-L-lysine hydroxylase and γ-butyrobetaine hydroxylase) that are necessary for synthesis of carnitine.[69][70] Carnitine is essential for the transport of fatty acids into mitochondria for ATP generation.

- The remaining three enzymes have the following functions in common, but have other functions as well:

- dopamine beta hydroxylase participates in the biosynthesis of norepinephrine from dopamine.[71][72]

- Peptidylglycine alpha-amidating monooxygenase amidates peptide hormones by removing the glyoxylate residue from their c-terminal glycine residues. This increases peptide hormone stability and activity.[73][74]

- 4-hydroxyphenylpyruvate dioxygenase modulates tyrosine metabolism.[75][76]

Immune system

Vitamin C is found in high concentrations in immune cells, and is consumed quickly during infections. It is not certain how vitamin C interacts with the immune system; it has been hypothesized to modulate the activities of phagocytes, the production of cytokines and lymphocytes, and the number of cell adhesion molecules in monocytes.[77]

Role in plants

Ascorbic acid is associated with chloroplasts and apparently plays a role in ameliorating the oxidative stress of photosynthesis. In addition, it has a number of other roles in cell division and protein modification. Plants appear to be able to make ascorbate by at least one other biochemical route that is different from the major route in animals, although precise details remain unknown.[78]

Daily requirements

The North American Dietary Reference Intake recommends 90 milligrams per day and no more than 2 grams (2,000 milligrams) per day.[79] Other related species sharing the same inability to produce vitamin C require exogenous vitamin C consumption 20 to 80 times this reference intake.[80] There is continuing debate within the scientific community over the best dose schedule (the amount and frequency of intake) of vitamin C for maintaining optimal health in humans.[81] A balanced diet without supplementation usually contains enough vitamin C to prevent scurvy in an average healthy adult, while those who are pregnant, smoke tobacco, or are under stress require slightly more.[79]

| United States vitamin C recommendations[79] | |

|---|---|

| Recommended Dietary Allowance (adult male) | 90 mg per day |

| Recommended Dietary Allowance (adult female) | 75 mg per day |

| Tolerable Upper Intake Level (adult male) | 2,000 mg per day |

| Tolerable Upper Intake Level (adult female) | 2,000 mg per day |

Government recommended intake

Recommendations for vitamin C intake have been set by various national agencies:

- 40 milligrams per day or 280 milligrams per week taken all at once: the United Kingdom's Food Standards Agency[1]

- 45 milligrams per day 300 milligrams per week: the World Health Organization[82]

- 80 milligrams per day: the European Commission's Council on nutrition labeling[83]

- 90 mg/day (males) and 75 mg/day (females): Health Canada 2007[84]

- 60–95 milligrams per day: United States' National Academy of Sciences.[79] The United States defined Tolerable Upper Intake Level for a 25-year-old male is 2,000 milligrams per day.

- 100 milligrams per day: Japan's National Institute of Health and Nutrition.[85] The NIHN did not set a Tolerable Upper Intake Level.

Testing for ascorbate levels in the body

Simple tests use dichlorophenolindophenol, a redox indicator, to measure the levels of vitamin C in the urine and in serum or blood plasma. However these reflect recent dietary intake rather than the level of vitamin C in body stores.[1] Reverse phase high performance liquid chromatography is used for determining the storage levels of vitamin C within lymphocytes and tissue. It has been observed that while serum or blood plasma levels follow the circadian rhythm or short term dietary changes, those within tissues themselves are more stable and give a better view of the availability of ascorbate within the organism. However, very few hospital laboratories are adequately equipped and trained to carry out such detailed analyses, and require samples to be analyzed in specialized laboratories.[86][87]

Adverse effects

Common side-effects

Relatively large doses of ascorbic acid may cause indigestion, particularly when taken on an empty stomach. However, taking vitamin C in the form of sodium ascorbate and calcium ascorbate may minimize this effect.[88] When taken in large doses, ascorbic acid causes diarrhea in healthy subjects. In one trial in 1936, doses of up to 6 grams of ascorbic acid were given to 29 infants, 93 children of preschool and school age, and 20 adults for more than 1400 days. With the higher doses, toxic manifestations were observed in five adults and four infants. The signs and symptoms in adults were nausea, vomiting, diarrhea, flushing of the face, headache, fatigue and disturbed sleep. The main toxic reactions in the infants were skin rashes.[89]

Possible side-effects

As vitamin C enhances iron absorption,[90][91] iron poisoning can become an issue to people with rare iron overload disorders, such as haemochromatosis. A genetic condition that results in inadequate levels of the enzyme glucose-6-phosphate dehydrogenase (G6PD) can cause sufferers to develop hemolytic anemia after ingesting specific oxidizing substances, such as very large dosages of vitamin C.

There is a longstanding belief among the mainstream medical community that vitamin C causes kidney stones, which is based on little science.[92] Although recent studies have found a relationship,[93][94] a clear link between excess ascorbic acid intake and kidney stone formation has not been generally established.[95] Some case reports exist for a link between patients with oxalate deposits and a history of high-dose vitamin C usage.[96]

In a study conducted on rats, during the first month of pregnancy, high doses of vitamin C may suppress the production of progesterone from the corpus luteum.[97] Progesterone, necessary for the maintenance of a pregnancy, is produced by the corpus luteum for the first few weeks, until the placenta is developed enough to produce its own source. By blocking this function of the corpus luteum, high doses of vitamin C (1000+ mg) are theorized to induce an early miscarriage. In a group of spontaneously aborting women at the end of the first trimester, the mean values of vitamin C were significantly higher in the aborting group. However, the authors do state: 'This could not be interpreted as an evidence of causal association.'[98] However, in a previous study of 79 women with threatened, previous spontaneous, or habitual abortion, Javert and Stander (1943) had 91% success with 33 patients who received vitamin C together with bioflavonoids and vitamin K (only three abortions), whereas all of the 46 patients who did not receive the vitamins aborted.[99]

A study in rats and humans suggested that adding Vitamin C supplements to an exercise training program lowered the expected effect of training on VO2 Max. Although the results in humans were not statistically significant, this study is often cited as evidence that high doses of Vitamin C have an adverse effect on exercise performance. In rats, it was shown that the additional Vitamin C resulted in lowered mitochondria production.[100] Since rats are able to produce all of their needed Vitamin C, however, it is questionable whether they offer a relevant model of human physiological processes in this regard.

A cancer-causing mechanism of hexavalent chromium may be triggered by vitamin C.[101]

Overdose

Vitamin C is water-soluble, with dietary excesses not absorbed, and excesses in the blood rapidly excreted in the urine. It exhibits remarkably low toxicity. The LD50 (the dose that will kill 50% of a population) in rats is generally accepted to be 11.9 grams per kilogram of body weight when given by forced gavage (orally). The mechanism of death from such doses (1.2% of body weight, or 0.84 kg for a 70 kg human) is unknown, but may be more mechanical than chemical.[102] The LD50 in humans remains unknown, given lack of any accidental or intentional poisoning death data. However, as with all substances tested in this way, the rat LD50 is taken as a guide to its toxicity in humans.

Dietary sources

The richest natural sources are fruits and vegetables, and of those, the Kakadu plum and the camu camu fruit contain the highest concentration of the vitamin. It is also present in some cuts of meat, especially liver. Vitamin C is the most widely taken nutritional supplement and is available in a variety of forms, including tablets, drink mixes, crystals in capsules or naked crystals.

Vitamin C is absorbed by the intestines using a sodium-ion dependent channel. It is transported through the intestine via both glucose-sensitive and glucose-insensitive mechanisms. The presence of large quantities of sugar either in the intestines or in the blood can slow absorption.[103]

Plant sources

While plants are generally a good source of vitamin C, the amount in foods of plant origin depends on the precise variety of the plant, soil condition, climate where it grew, length of time since it was picked, storage conditions, and method of preparation.[104]

The following table is approximate and shows the relative abundance in different raw plant sources.[105][106] As some plants were analyzed fresh while others were dried (thus, artifactually increasing concentration of individual constituents like vitamin C), the data are subject to potential variation and difficulties for comparison. The amount is given in milligrams per 100 grams of fruit or vegetable and is a rounded average from multiple authoritative sources:

| Plant source | Amount (mg / 100g) |

|---|---|

| Kakadu plum | 1000–5300[107][108][109] |

| Camu Camu | 2800[106][110] |

| Acerola | 1677[111] |

| Seabuckthorn | 695 |

| Indian gooseberry | 445 |

| Rose hip | 426[112] |

| Baobab | 400 |

| Chili pepper (green) | 244 |

| Guava (common, raw) | 228.3[113] |

| Blackcurrant | 200 |

| Red pepper | 190 |

| Chili pepper (red) | 144 |

| Parsley | 130 |

| Kiwifruit | 90 |

| Broccoli | 90 |

| Loganberry | 80 |

| Redcurrant | 80 |

| Brussels sprouts | 80 |

| Wolfberry (Goji) | 73 † |

| Lychee | 70 |

| Persimmon (native, raw) | 66.0[114] |

| Cloudberry | 60 |

| Elderberry | 60 |

† average of 3 sources; dried

| Plant source | Amount (mg / 100g) |

|---|---|

| Papaya | 60 |

| Strawberry | 60 |

| Orange | 53 |

| Lemon | 53 |

| Pineapple | 48 |

| Cauliflower | 48 |

| Kale | 41 |

| Melon, cantaloupe | 40 |

| Garlic | 31 |

| Grapefruit | 30 |

| Raspberry | 30 |

| Tangerine | 30 |

| Mandarin orange | 30 |

| Passion fruit | 30 |

| Spinach | 30 |

| Cabbage raw green | 30 |

| Lime | 30 |

| Mango | 28 |

| Blackberry | 21 |

| Potato | 20 |

| Melon, honeydew | 20 |

| Tomato, red | 13.7[115] |

| Cranberry | 13 |

| Tomato | 10 |

| Blueberry | 10 |

| Pawpaw | 10 |

| Plant source | Amount (mg / 100g) |

|---|---|

| Grape | 10 |

| Apricot | 10 |

| Plum | 10 |

| Watermelon | 10 |

| Banana | 9 |

| Avocado | 8.8[116] |

| Crabapple | 8 |

| Onion | 7.4[117] |

| Cherry | 7 |

| Peach | 7 |

| Carrot | 6 |

| Apple | 6 |

| Asparagus | 6 |

| Horned melon | 5.3[118] |

| Beetroot | 5 |

| Chokecherry | 5 |

| Pear | 4 |

| Lettuce | 4 |

| Cucumber | 3 |

| Eggplant | 2 |

| Raisin | 2 |

| Fig | 2 |

| Bilberry | 1 |

| Medlar | 0.3 |

Source:[119]

Animal sources

The overwhelming majority of species of animals (but not humans or guinea pigs) and plants synthesize their own vitamin C.[122] Therefore, some animal products can be used as sources of dietary vitamin C.

Vitamin C is most present in the liver and least present in the muscle. Since muscle provides the majority of meat consumed in the western human diet, animal products are not a reliable source of the vitamin. Vitamin C is present in human breast milk, but only in limited quantity in raw cow's milk.[123] All excess vitamin C is disposed of through the urinary system.

The following table shows the relative abundance of vitamin C in various foods of animal origin, given in milligrams of vitamin C per 100 grams of food:

| Animal Source | Amount (mg / 100g) |

|---|---|

| calf liver (raw) | 36 |

| Beef liver (raw) | 31 |

| Oysters (raw) | 30 |

| Cod roe (fried) | 26 |

| Pork liver (raw) | 23 |

| Lamb brain (boiled) | 17 |

| Chicken liver (fried) | 13 |

| Animal Source | Amount (mg / 100g) |

|---|---|

| Lamb liver (fried) | 12 |

| calf adrenals (raw) | 11[124] |

| Lamb heart (roast) | 11 |

| Lamb tongue (stewed) | 6 |

| Camel milk (fresh) | 5[125] |

| Human milk (fresh) | 4 |

| Goat milk (fresh) | 2 |

| Cow milk (fresh) | 2 |

Food preparation

Vitamin C chemically decomposes under certain conditions, many of which may occur during the cooking of food. Vitamin C concentrations in various food substances decrease with time in proportion to the temperature they are stored at[126] and cooking can reduce the Vitamin C content of vegetables by around 60% possibly partly due to increased enzymatic destruction as it may be more significant at sub-boiling temperatures.[127] Longer cooking times also add to this effect, as will copper food vessels, which catalyse the decomposition.[102]

Another cause of vitamin C being lost from food is leaching, where the water-soluble vitamin dissolves into the cooking water, which is later poured away and not consumed. However, vitamin C does not leach in all vegetables at the same rate; research shows broccoli seems to retain more than any other.[128] Research has also shown that freshly cut fruits do not lose significant nutrients when stored in the refrigerator for a few days.[129]

Supplements

Vitamin C is available in caplets, tablets, capsules, drink mix packets, in multi-vitamin formulations, in multiple antioxidant formulations, and as crystalline powder. Timed release versions are available, as are formulations containing bioflavonoids such as quercetin, hesperidin, and rutin. Tablet and capsule sizes range from 25 mg to 1500 mg. Vitamin C (as ascorbic acid) crystals are typically available in bottles containing 300 g to 1 kg of powder (a 5 ml teaspoon of vitamin C crystals equals 5,000 mg). The bottles are usually airtight and brown or opaque in order to prevent oxidation, in which case the vitamin C would become useless, if not damaging[citation needed].

Industrial synthesis

Vitamin C is produced from glucose by two main routes. The Reichstein process, developed in the 1930s, uses a single pre-fermentation followed by a purely chemical route. The modern two-step fermentation process, originally developed in China in the 1960s, uses additional fermentation to replace part of the later chemical stages. Both processes yield approximately 60% vitamin C from the glucose feed.[130]

Research is underway at the Scottish Crop Research Institute in the interest of creating a strain of yeast that can synthesize vitamin C in a single fermentation step from galactose, a technology expected to reduce manufacturing costs considerably.[22]

World production of synthesized vitamin C is currently estimated at approximately 110,000 tonnes annually. The main producers have been BASF/Takeda, DSM, Merck and the China Pharmaceutical Group Ltd. of the People's Republic of China. By 2008 only the DSM plant in Scotland remained operational outside the strong price competition from China.[131] The world price of vitamin C rose sharply in 2008 partly as a result of rises in basic food prices but also in anticipation of a stoppage of the two Chinese plants, situated at Shijiazhuang near Beijing, as part of a general shutdown of polluting industry in China over the period of the Olympic games.[132] Five Chinese manufacturers met in 2010, among them Northeast Pharmaceutical Group and North China Pharmaceutical Group, and agreed to temporarily stop production in order to maintain prices.[133] In 2011 an American suit was filed against four Chinese companies that allegedly colluded to limit production and fix prices of vitamin C in the United States. According to the plaintiffs, after the agreement was made spot prices for vitamin C shot to as high as $7 per kilogram in December 2002 from $2.50 per kilogram in December 2001. The companies did not deny the accusation but say in their defense that the Chinese government compelled them to act in this way.[134] In January 2012 a US judge ruled that the Chinese companies can be sued in the U.S. by buyers acting as a group.[135]

Food fortification

In 2005, Health Canada evaluated the effect of fortification of foods with ascorbate in the guidance document, Addition of Vitamins and Minerals to Food.[136] Ascorbate was categorized as a 'Risk Category A nutrient', meaning it is a nutrient for which an upper limit for intake is set but allows a wide margin of intake that has a narrow margin of safety but non-serious critical adverse effects.[136]

Compendial status

History

The need to include fresh plant food or raw animal flesh in the diet to prevent disease was known from ancient times. Native people living in marginal areas incorporated this into their medicinal lore. For example, spruce needles were used in temperate zones in infusions, or the leaves from species of drought-resistant trees in desert areas. In 1536, the French explorers Jacques Cartier and Daniel Knezevic, exploring the St. Lawrence River, used the local natives' knowledge to save his men who were dying of scurvy. He boiled the needles of the arbor vitae tree to make a tea that was later shown to contain 50 mg of vitamin C per 100 grams.[139][140]

In the 1497 expedition of Vasco de Gama, the curative effects of citrus fruit were known.[141][142] The Portuguese planted fruit trees and vegetables in Saint Helena, a stopping point for homebound voyages from Asia, and left their sick, suffering from scurvy and other ailments to be taken home, if they recovered, by the next ship.[143]

Authorities occasionally recommended the benefit of plant food to promote health and prevent scurvy during long sea voyages. John Woodall, the first appointed surgeon to the British East India Company, recommended the preventive and curative use of lemon juice in his book, The Surgeon's Mate, in 1617.[144] The Dutch writer, Johann Bachstrom, in 1734, gave the firm opinion that "scurvy is solely owing to a total abstinence from fresh vegetable food, and greens, which is alone the primary cause of the disease."[145][146]

Scurvy had long been a principal killer of sailors during the long sea voyages.[147] According to Jonathan Lamb, "In 1499, Vasco da Gama lost 116 of his crew of 170; In 1520, Magellan lost 208 out of 230;...all mainly to scurvy."[148]

While the earliest documented case of scurvy was described by Hippocrates around 400 BC, the first attempt to give scientific basis for the cause of this disease was by a ship's surgeon in the British Royal Navy, James Lind. Scurvy was common among those with poor access to fresh fruit and vegetables, such as remote, isolated sailors and soldiers. While at sea in May 1747, Lind provided some crew members with two oranges and one lemon per day, in addition to normal rations, while others continued on cider, vinegar, sulfuric acid or seawater, along with their normal rations. In the history of science, this is considered to be the first occurrence of a controlled experiment. The results conclusively showed that citrus fruits prevented the disease. Lind published his work in 1753 in his Treatise on the Scurvy.[149]

Lind's work was slow to be noticed, partly because his Treatise was not published until six years after his study, and also because he recommended a lemon juice extract known as rob.[150] Fresh fruit was very expensive to keep on board, whereas boiling it down to juice allowed easy storage but destroyed the vitamin (especially if boiled in copper kettles).[102] Ship captains concluded wrongly that Lind's other suggestions were ineffective because those juices failed to prevent or cure scurvy.

It was 1795 before the British navy adopted lemons or lime as standard issue at sea. Limes were more popular, as they could be found in British West Indian Colonies, unlike lemons, which were not found in British Dominions, and were therefore more expensive. This practice led to the American use of the nickname "limey" to refer to the British. Captain James Cook had previously demonstrated and proven the principle of the advantages of carrying "Sour krout" on board, by taking his crews to the Hawaiian Islands and beyond without losing any of his men to scurvy.[151] For this otherwise unheard of feat, the British Admiralty awarded him a medal.

The name antiscorbutic was used in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries as general term for those foods known to prevent scurvy, even though there was no understanding of the reason for this. These foods included but were not limited to: lemons, limes, and oranges; sauerkraut, cabbage, malt, and portable soup.[152]

Even before the antiscorbutic substance was identified, there were indications that it was present in amounts sufficient to prevent scurvy, in nearly all fresh (uncooked and uncured) foods, including raw animal-derived foods. In 1928, the Arctic anthropologist Vilhjalmur Stefansson attempted to prove his theory of how the Inuit are able to avoid scurvy with almost no plant food in their diet, despite the disease's striking European Arctic explorers living on similar high cooked-meat diets. Stefansson theorised that the natives get their vitamin C from fresh meat that is minimally cooked. Starting in February 1928, for one year he and a colleague lived on an exclusively minimally cooked meat diet while under medical supervision; they remained healthy. Later studies done after vitamin C could be quantified in mostly raw traditional food diets of the Yukon First Nations, Dene, Inuit, and Métis of the Northern Canada, showed that their daily intake of vitamin C averaged between 52 and 62 mg/day, an amount approximately the dietary reference intake (DRI), even at times of the year when little plant-based food was eaten.[153]

Discovery

In 1907 a laboratory animal model which would help to isolate and identify the antiscorbutic factor was discovered: Axel Holst and Theodor Frølich, two Norwegian physicians studying shipboard beriberi in the Norwegian fishing fleet, wanted a small test mammal to substitute for the pigeons then used in beriberi research. They fed guinea pigs their test diet of grains and flour, which had earlier produced beriberi in their pigeons, and were surprised when classic scurvy resulted instead. This was a serendipitous choice of animal. Until that time, scurvy had not been observed in any organism apart from humans, and had been considered an exclusively human disease. (Pigeons, as seed-eating birds, make their own vitamin C.) Holst and Frølich found they could cure the disease in guinea pigs with the addition of various fresh foods and extracts. This discovery of an animal experimental model for scurvy, made even before the essential idea of vitamins in foods had even been put forward, has been called the single most important piece of vitamin C research.[155]

In 1912, the Polish American biochemist Casimir Funk, while researching beriberi in pigeons, developed the concept of vitamins to refer to the non-mineral micronutrients that are essential to health. The name is a blend of "vital", due to the vital biochemical role they play, and "amines" because Funk thought that all these materials were chemical amines. Although the "e" was dropped after skepticism that all these compounds were amines, the word vitamin remained as a generic name for them. One of the vitamins was thought to be the hypothesised anti-scorbutic factor in certain foods, such as those tested by Holst and Frølich. In 1928, this vitamin was referred to as "water-soluble C," although its chemical structure had still not been determined.[156]

From 1928 to 1932, the Hungarian research team of Albert Szent-Györgyi and Joseph L. Svirbely, as well as the American team led by Charles Glen King in Pittsburgh, first identified the anti-scorbutic factor. Szent-Györgyi had isolated the chemical hexuronic acid (actually, L-hexuronic acid) from animal adrenal glands at the Mayo clinic, and suspected it to be the antiscorbutic factor but could not prove it without a biological assay. At the same time, for five years King's laboratory at the University of Pittsburgh had been trying to isolate the antiscorbutic factor in lemon juice using the original 1907 model of scorbutic guinea pigs which developed scurvy when not fed fresh foods but were cured by lemon juice. They had also considered hexuronic acid, but had been put off the trail when a coworker made the explicit (and mistaken) experimental claim that this substance was not the antiscorbutic substance.[157]

Finally, in late 1931, Szent-Györgyi gave Svirbely, formerly of King's lab, the last of his hexuronic acid with the suggestion that it might be the anti-scorbutic factor. By the spring of 1932, King's laboratory had proven this but published the result without giving Szent-Györgyi credit for it, leading to a bitter dispute over priority claims (in reality it had taken a team effort by both groups, since Szent-Györgyi was unwilling to do the difficult and messy animal studies).[157]

Meanwhile, by 1932, Szent-Györgyi had moved to Hungary and his group had discovered that paprika peppers, a common spice in the Hungarian diet, was a rich source of hexuronic acid, the antiscorbutic factor. With a new and plentiful source of the vitamin, Szent-Györgyi sent a sample to noted British sugar chemist Walter Norman Haworth, who chemically identified it and proved the identification by synthesis in 1933.[158][159][160] Haworth and Szent-Györgyi now proposed that the substance L-hexuronic acid be called a-scorbic acid, and chemically L-ascorbic acid, in honor of its activity against scurvy.[161] Ascorbic acid turned out not to be an amine, nor even to contain any nitrogen.

In part, in recognition of his accomplishment with vitamin C, Szent-Györgyi was awarded the unshared 1937 Nobel Prize in Medicine.[162] Haworth also shared that year's Nobel Prize in Chemistry, in part for his vitamin C synthetic work.[154]

Between 1933 and 1934 not only Haworth and Edmund Hirst had synthesized vitamin C, but also, independently, Tadeus Reichstein succeeded in synthesizing the vitamin in bulk, making it the first vitamin to be artificially produced.[163] The latter process made possible the cheap mass-production of semi-synthetic vitamin C, which was quickly marketed. Only Haworth was awarded the 1937 Nobel Prize in Chemistry in part for this work, but the Reichstein process, a combined chemical and bacterial fermentation sequence still used today to produce vitamin C, retained Reichstein's name.[164][165] In 1934 Hoffmann–La Roche, which bought the Reichstein process patent, became the first pharmaceutical company to mass-produce and market synthetic vitamin C, under the brand name of Redoxon.[166]

In 1957, J.J. Burns showed that the reason some mammals are susceptible to scurvy is the inability of their liver to produce the active enzyme L-gulonolactone oxidase, which is the last of the chain of four enzymes that synthesize vitamin C.[167][168] American biochemist Irwin Stone was the first to exploit vitamin C for its food preservative properties. He later developed the theory that humans possess a mutated form of the L-gulonolactone oxidase coding gene.[169]

In 2008, researchers at the University of Montpellier discovered that in humans and other primates the red blood cells have evolved a mechanism to more efficiently utilize the vitamin C present in the body by recycling oxidized L-dehydroascorbic acid (DHA) back into ascorbic acid which can be reused by the body. The mechanism was not found to be present in mammals that synthesize their own vitamin C.[19]

Society and culture

In February 2011, the Swiss Post issued a postage stamp bearing a depiction of a model of a molecule of vitamin C to mark the International Year of Chemistry. Tadeus Reichstein synthesized the vitamin for the first time in 1933.[170]

Measurement of vitamin C in foods

Vitamin C content of a food sample such as fruit juice can be calculated by measuring the volume of the sample required to decolorize a solution of dichlorophenolindophenol (DCPIP) and then calibrating the results by comparison with a known concentration of vitamin C.[171][172]

See also

References

- ^ a b c d "Vitamin C". Food Standards Agency (UK). Retrieved February 19, 2007.

- ^ Padayatty SJ, Katz A, Wang Y, Eck P, Kwon O, Lee JH, Chen S, Corpe C, Dutta A, Dutta SK, Levine M (February 2003). "Vitamin C as an antioxidant: evaluation of its role in disease prevention". J Am Coll Nutr. 22 (1): 18–35. doi:10.1080/07315724.2003.10719272. PMID 12569111.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ a b Aboul-Enein HY, Al-Duraibi IA, Stefan RI, Radoi C, Avramescu A (1999). "Analysis of L- and D-ascorbic acid in fruits and fruit drinks by HPLC" (PDF). Seminars in Food Analysis. 4 (1): 31–37. Archived from the original (PDF) on December 15, 2013.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ "Vitamin C". University of Maryland Medical Center. January 2007. Retrieved March 31, 2008.

- ^ a b Higdon J (January 31, 2006). "Vitamin C". Oregon State University, Micronutrient Information Center. Retrieved March 7, 2007.

- ^ Meister A (April 1994). "Glutathione-ascorbic acid antioxidant system in animals". J. Biol. Chem. 269 (13): 9397–400. PMID 8144521.

- ^ Michels A, Frei B (2012). "Vitamin C". In Caudill MA, Rogers M (ed.). Biochemical, Physiological, and Molecular Aspects of Human Nutrition (3 ed.). Philadelphia: Saunders. pp. 627–654. ISBN 1-4377-0959-1.

- ^ a b Gropper SS, Smith JL, Grodd JL (2005). Advanced nutrition and human metabolism. Belmont, CA: Thomson Wadsworth. pp. 260–275. ISBN 0-534-55986-7.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Wheeler GL, Jones MA, Smirnoff N (May 1998). "The biosynthetic pathway of vitamin C in higher plants". Nature. 393 (6683): 365–9. Bibcode:1998Natur.393..365W. doi:10.1038/30728. PMID 9620799.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Bánhegyi G, Mándl J (2001). "The hepatic glycogenoreticular system". Pathol. Oncol. Res. 7 (2): 107–10. doi:10.1007/BF03032575. PMID 11458272.

- ^ a b Martinez del Rio C (July 1997). "Can passerines synthesize vitamin C?". The Auk. 114 (3): 513–16. doi:10.2307/4089257. JSTOR 4089257. Retrieved May 2, 2011.

- ^ Drouin G, Godin JR, Pagé B (2011). "The genetics of vitamin C loss in vertebrates". Curr. Genomics. 12 (5): 371–8. doi:10.2174/138920211796429736. PMC 3145266. PMID 22294879.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Jenness R, Birney E, Ayaz K (1980). "Variation of l-gulonolactone oxidase activity in placental mammals". Comparative Biochemistry and Physiology Part B: Biochemistry and Molecular Biology. 67 (2): 195–204. doi:10.1016/0305-0491(80)90131-5.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Cui J, Pan YH, Zhang Y, Jones G, Zhang S (February 2011). "Progressive pseudogenization: vitamin C synthesis and its loss in bats". Mol. Biol. Evol. 28 (2): 1025–31. doi:10.1093/molbev/msq286. PMID 21037206.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Cui J, Yuan X, Wang L, Jones G, Zhang S (November 2011). "Recent loss of vitamin C biosynthesis ability in bats". PLoS ONE. 6 (11): e27114. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0027114. PMC 3206078. PMID 22069493.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) CS1 maint: unflagged free DOI (link) - ^ Harris JW (1996). Ascorbic acid: biochemistry and biomedical cell biology. New York: Plenum Press. p. 35. ISBN 0-306-45148-4.

- ^ Nishikimi M, Kawai T, Yagi K (October 1992). "Guinea pigs possess a highly mutated gene for L-gulono-gamma-lactone oxidase, the key enzyme for L-ascorbic acid biosynthesis missing in this species". J. Biol. Chem. 267 (30): 21967–72. PMID 1400507.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Ohta Y, Nishikimi M (October 1999). "Random nucleotide substitutions in primate nonfunctional gene for L-gulono-gamma-lactone oxidase, the missing enzyme in L-ascorbic acid biosynthesis". Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 1472 (1–2): 408–11. doi:10.1016/S0304-4165(99)00123-3. PMID 10572964.

- ^ a b Montel-Hagen A, Kinet S, Manel N, Mongellaz C, Prohaska R, Battini JL, Delaunay J, Sitbon M, Taylor N (March 2008). "Erythrocyte Glut1 triggers dehydroascorbic acid uptake in mammals unable to synthesize vitamin C". Cell. 132 (6): 1039–48. doi:10.1016/j.cell.2008.01.042. PMID 18358815.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|laydate=ignored (help); Unknown parameter|laysource=ignored (help); Unknown parameter|laysummary=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Milton K (June 1999). "Nutritional characteristics of wild primate foods: do the diets of our closest living relatives have lessons for us?". Nutrition. 15 (6): 488–98. doi:10.1016/S0899-9007(99)00078-7. PMID 10378206.

- ^ "Vitamin C". Nutrient Reference Values for Australia and New Zealand. Retrieved April 17, 2015.

- ^ a b Hancock RD, Viola R. "Ascorbic acid biosynthesis in higher plants and microorganisms" (PDF). Scottish Crop Research Institute. Retrieved February 20, 2007.

- ^ Hancock RD, Galpin JR, Viola R (May 2000). "Biosynthesis of L-ascorbic acid (vitamin C) by Saccharomyces cerevisiae". FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 186 (2): 245–50. doi:10.1111/j.1574-6968.2000.tb09112.x. PMID 10802179.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Hardie LJ, Fletcher TC, Secombes CJ (1991). "The effect of dietary vitamin C on the immune response of the Atlantic salmon (Salmo salar L.)". Aquaculture. 95 (3–4): 201–14. doi:10.1016/0044-8486(91)90087-N.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Challem JJ, Taylor EW (July 1998). "Retroviruses, ascorbate, and mutations, in the evolution of Homo sapiens". Free Radic. Biol. Med. 25 (1): 130–2. doi:10.1016/S0891-5849(98)00034-3. PMID 9655531.

- ^ Bánhegyi G, Braun L, Csala M, Puskás F, Mandl J (1997). "Ascorbate metabolism and its regulation in animals". Free Radic. Biol. Med. 23 (5): 793–803. doi:10.1016/S0891-5849(97)00062-2. PMID 9296457.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Stone I (June 1979). "Homo sapiens ascorbicus, a biochemically corrected robust human mutant". Med. Hypotheses. 5 (6): 711–21. doi:10.1016/0306-9877(79)90093-8. PMID 491997.

- ^ Pollock JI, Mullin RJ (May 1987). "Vitamin C biosynthesis in prosimians: evidence for the anthropoid affinity of Tarsius". Am. J. Phys. Anthropol. 73 (1): 65–70. doi:10.1002/ajpa.1330730106. PMID 3113259.

- ^ Poux C, Douzery EJ (May 2004). "Primate phylogeny, evolutionary rate variations, and divergence times: a contribution from the nuclear gene IRBP". Am. J. Phys. Anthropol. 124 (1): 1–16. doi:10.1002/ajpa.10322. PMID 15085543.

- ^ Goodman M, Porter CA, Czelusniak J, Page SL, Schneider H, Shoshani J, Gunnell G, Groves CP (June 1998). "Toward a phylogenetic classification of Primates based on DNA evidence complemented by fossil evidence". Mol. Phylogenet. Evol. 9 (3): 585–98. doi:10.1006/mpev.1998.0495. PMID 9668008.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Porter CA, Page SL, Czelusniak J, Schneider H, Schneider MPC, Sampaio I, Goodman M (January 1997). "Phylogeny and Evolution of Selected Primates as Determined by Sequences of the ε-Globin Locus and 5′ Flanking Regions". International Journal of Primatology. 18 (2): 261–295. doi:10.1023/A:1026328804319.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Proctor P (November 1970). "Similar functions of uric acid and ascorbate in man?". Nature. 228 (5274): 868. Bibcode:1970Natur.228..868P. doi:10.1038/228868a0. PMID 5477017.

- ^ a b Savini I, Rossi A, Pierro C, Avigliano L, Catani MV (April 2008). "SVCT1 and SVCT2: key proteins for vitamin C uptake". Amino Acids. 34 (3): 347–55. doi:10.1007/s00726-007-0555-7. PMID 17541511.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Rumsey SC, Kwon O, Xu GW, Burant CF, Simpson I, Levine M (July 1997). "Glucose transporter isoforms GLUT1 and GLUT3 transport dehydroascorbic acid". J. Biol. Chem. 272 (30): 18982–9. doi:10.1074/jbc.272.30.18982. PMID 9228080.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) CS1 maint: unflagged free DOI (link) - ^ May JM, Qu ZC, Neel DR, Li X (May 2003). "Recycling of vitamin C from its oxidized forms by human endothelial cells". Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 1640 (2–3): 153–61. doi:10.1016/S0167-4889(03)00043-0. PMID 12729925.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Packer L (1997). "Vitamin C and redox cycling antioxidants". In Fuchs J, Packer L (ed.). Vitamin C in health and disease. New York: M. Dekker. ISBN 0-8247-9313-7. [page needed]

- ^ May JM, Qu ZC, Qiao H, Koury MJ (August 2007). "Maturational loss of the vitamin C transporter in erythrocytes". Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 360 (1): 295–8. doi:10.1016/j.bbrc.2007.06.072. PMC 1964531. PMID 17586466.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Sotiriou S, Gispert S, Cheng J, Wang Y, Chen A, Hoogstraten-Miller S, Miller GF, Kwon O, Levine M, Guttentag SH, Nussbaum RL (May 2002). "Ascorbic-acid transporter Slc23a1 is essential for vitamin C transport into the brain and for perinatal survival". Nat. Med. 8 (5): 514–7. doi:10.1038/nm0502-514. PMID 11984597.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Levine M, Conry-Cantilena C, Wang Y, Welch RW, Washko PW, Dhariwal KR, Park JB, Lazarev A, Graumlich JF, King J, Cantilena LR (April 1996). "Vitamin C pharmacokinetics in healthy volunteers: evidence for a recommended dietary allowance". Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 93 (8): 3704–9. Bibcode:1996PNAS...93.3704L. doi:10.1073/pnas.93.8.3704. PMC 39676. PMID 8623000.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Oreopoulos DG, Lindeman RD, VanderJagt DJ, Tzamaloukas AH, Bhagavan HN, Garry PJ (October 1993). "Renal excretion of ascorbic acid: effect of age and sex". J Am Coll Nutr. 12 (5): 537–42. doi:10.1080/07315724.1993.10718349. PMID 8263270.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Hediger MA (May 2002). "New view at C". Nat. Med. 8 (5): 445–6. doi:10.1038/nm0502-445. PMID 11984580.

- ^ a b MedlinePlus Encyclopedia: Ascorbic acid

- ^ "Statistics Canada, Canadian Community Health Survey, Cycle 2.2, Nutrition". 2004. Archived from the original on March 29, 2010. Retrieved November 20, 2014.

- ^ Pemberton J (June 2006). "Medical experiments carried out in Sheffield on conscientious objectors to military service during the 1939-45 war". Int J Epidemiol. 35 (3): 556–8. doi:10.1093/ije/dyl020. PMID 16510534.

- ^ Hodges RE, Baker EM, Hood J, Sauberlich HE, March SC (May 1969). "Experimental scurvy in man". Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 22 (5): 535–48. PMID 4977512.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ a b Stratton J, Godwin M (June 2011). "The effect of supplemental vitamins and minerals on the development of prostate cancer: a systematic review and meta-analysis". Fam Pract. 28 (3): 243–52. doi:10.1093/fampra/cmq115. PMID 21273283.

- ^ Bjelakovic G, Nikolova D, Gluud LL, Simonetti RG, Gluud C (2012). "Antioxidant supplements for prevention of mortality in healthy participants and patients with various diseases". Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 3: CD007176. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD007176.pub2. PMID 22419320.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Cortés-Jofré M, Rueda JR, Corsini-Muñoz G, Fonseca-Cortés C, Caraballoso M, Bonfill Cosp X (2012). "Drugs for preventing lung cancer in healthy people". Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 10: CD002141. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD002141.pub2. PMID 23076895.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Luo J, Shen L, Zheng D (2014). "Association between vitamin C intake and lung cancer: a dose-response meta-analysis". Sci Rep. 4: 6161. doi:10.1038/srep06161. PMID 25145261.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Xu X, Yu E, Liu L, Zhang W, Wei X, Gao X, Song N, Fu C (November 2013). "Dietary intake of vitamins A, C, and E and the risk of colorectal adenoma: a meta-analysis of observational studies". Eur. J. Cancer Prev. 22 (6): 529–39. doi:10.1097/CEJ.0b013e328364f1eb. PMID 24064545.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Papaioannou D, Cooper KL, Carroll C, Hind D, Squires H, Tappenden P, Logan RF (October 2011). "Antioxidants in the chemoprevention of colorectal cancer and colorectal adenomas in the general population: a systematic review and meta-analysis". Colorectal Dis. 13 (10): 1085–99. doi:10.1111/j.1463-1318.2010.02289.x. PMID 20412095.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Fulan H, Changxing J, Baina WY, Wencui Z, Chunqing L, Fan W, Dandan L, Dianjun S, Tong W, Da P, Yashuang Z (October 2011). "Retinol, vitamins A, C, and E and breast cancer risk: a meta-analysis and meta-regression". Cancer Causes Control. 22 (10): 1383–96. doi:10.1007/s10552-011-9811-y. PMID 21761132.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Harris HR, Orsini N, Wolk A (May 2014). "Vitamin C and survival among women with breast cancer: a meta-analysis". Eur. J. Cancer. 50 (7): 1223–31. doi:10.1016/j.ejca.2014.02.013. PMID 24613622.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Ye Y, Li J, Yuan Z (2013). "Effect of antioxidant vitamin supplementation on cardiovascular outcomes: a meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials". PLoS ONE. 8 (2): e56803. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0056803. PMC 3577664. PMID 23437244.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) CS1 maint: unflagged free DOI (link) - ^ Chen GC, Lu DB, Pang Z, Liu QF (2013). "Vitamin C intake, circulating vitamin C and risk of stroke: a meta-analysis of prospective studies". J Am Heart Assoc. 2 (6): e000329. doi:10.1161/JAHA.113.000329. PMC 3886767. PMID 24284213.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Effect of vitamin C on endothelial function in health and disease: A systematic review and meta-analysis of randomised controlled trials Atherosclerosis Volume 235, Issue 1, Pages 9–20, July 2014. Published April 16, 2014. Accessed June 25, 2014.

- ^ Rosenbaum CC, O'Mathúna DP, Chavez M, Shields K (2010). "Antioxidants and antiinflammatory dietary supplements for osteoarthritis and rheumatoid arthritis". Altern Ther Health Med. 16 (2): 32–40. PMID 20232616.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Crichton GE, Bryan J, Murphy KJ (September 2013). "Dietary antioxidants, cognitive function and dementia--a systematic review". Plant Foods Hum Nutr. 68 (3): 279–92. doi:10.1007/s11130-013-0370-0. PMID 23881465.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Li FJ, Shen L, Ji HF (2012). "Dietary intakes of vitamin E, vitamin C, and β-carotene and risk of Alzheimer's disease: a meta-analysis". J. Alzheimers Dis. 31 (2): 253–8. doi:10.3233/JAD-2012-120349. PMID 22543848.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Harrison FE (2012). "A critical review of vitamin C for the prevention of age-related cognitive decline and Alzheimer's disease". J. Alzheimers Dis. 29 (4): 711–26. doi:10.3233/JAD-2012-111853. PMC 3727637. PMID 22366772.

- ^ Mathew MC, Ervin AM, Tao J, Davis RM (2012). "Routine Antioxidant vitamin supplementation for preventing and slowing the progression of age-related cataract". Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 6: CD004567. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD004567.pub2. PMID 22696344.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ a b Douglas RM, Hemilä H, Chalker E, Treacy B (2007). Hemilä, Harri (ed.). "Vitamin C for preventing and treating the common cold". Cochrane Database Syst Rev (3): CD000980. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD000980.pub3. PMID 17636648.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Heimer KA, Hart AM, Martin LG, Rubio-Wallace S (May 2009). "Examining the evidence for the use of vitamin C in the prophylaxis and treatment of the common cold". J Am Acad Nurse Pract. 21 (5): 295–300. doi:10.1111/j.1745-7599.2009.00409.x. PMID 19432914.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Hemilä H, Chalker E (January 2013). "Vitamin C for preventing and treating the common cold". Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 1: CD000980. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD000980.pub4. PMID 23440782.

- ^ a b Levine M, Rumsey SC, Wang Y, Park JB, Daruwala R (2000). "Vitamin C". In Stipanuk MH (ed.). Biochemical and physiological aspects of human nutrition. Philadelphia: W.B. Saunders. pp. 541–67. ISBN 0-7216-4452-X.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Prockop DJ, Kivirikko KI (1995). "Collagens: molecular biology, diseases, and potentials for therapy". Annu. Rev. Biochem. 64: 403–34. doi:10.1146/annurev.bi.64.070195.002155. PMID 7574488.

- ^ Peterkofsky B (December 1991). "Ascorbate requirement for hydroxylation and secretion of procollagen: relationship to inhibition of collagen synthesis in scurvy". Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 54 (6 Suppl): 1135S–1140S. PMID 1720597.

- ^ Kivirikko KI, Myllylä R (1985). "Post-translational processing of procollagens". Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences. 460: 187–201. Bibcode:1985NYASA.460..187K. doi:10.1111/j.1749-6632.1985.tb51167.x. PMID 3008623.

- ^ Rebouche CJ (December 1991). "Ascorbic acid and carnitine biosynthesis". Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 54 (6 Suppl): 1147S–1152S. PMID 1962562.

- ^ Dunn WA, Rettura G, Seifter E, Englard S (September 1984). "Carnitine biosynthesis from gamma-butyrobetaine and from exogenous protein-bound 6-N-trimethyl-L-lysine by the perfused guinea pig liver. Effect of ascorbate deficiency on the in situ activity of gamma-butyrobetaine hydroxylase" (PDF). J. Biol. Chem. 259 (17): 10764–70. PMID 6432788.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Levine M, Dhariwal KR, Washko P, Welch R, Wang YH, Cantilena CC, Yu R (1992). "Ascorbic acid and reaction kinetics in situ: a new approach to vitamin requirements". J. Nutr. Sci. Vitaminol. Spec No: 169–72. doi:10.3177/jnsv.38.Special_169. PMID 1297733.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Kaufman S (1974). "Dopamine-beta-hydroxylase". J Psychiatr Res. 11: 303–16. doi:10.1016/0022-3956(74)90112-5. PMID 4461800.

- ^ Eipper BA, Milgram SL, Husten EJ, Yun HY, Mains RE (April 1993). "Peptidylglycine alpha-amidating monooxygenase: a multifunctional protein with catalytic, processing, and routing domains". Protein Sci. 2 (4): 489–97. doi:10.1002/pro.5560020401. PMC 2142366. PMID 8518727.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Eipper BA, Stoffers DA, Mains RE (1992). "The biosynthesis of neuropeptides: peptide alpha-amidation". Annu. Rev. Neurosci. 15: 57–85. doi:10.1146/annurev.ne.15.030192.000421. PMID 1575450.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Englard S, Seifter S (1986). "The biochemical functions of ascorbic acid". Annu. Rev. Nutr. 6: 365–406. doi:10.1146/annurev.nu.06.070186.002053. PMID 3015170.

- ^ Lindblad B, Lindstedt G, Lindstedt S (December 1970). "The mechanism of enzymic formation of homogentisate from p-hydroxyphenylpyruvate". J. Am. Chem. Soc. 92 (25): 7446–9. doi:10.1021/ja00728a032. PMID 5487549.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Preedy VR, Watson RR, Sherma Z (2010). Dietary Components and Immune Function (Nutrition and Health). Totowa, NJ: Humana Press. pp. 36, 52. ISBN 1-60761-060-4.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Smirnoff N (1996). "BOTANICAL BRIEFING: The Function and Metabolism of Ascorbic Acid in Plants". Annals of Botany. 78 (6): 661–9. doi:10.1006/anbo.1996.0175.

- ^ a b c d Food and Nutrition Board, Institute of Medicine. "Dietary Reference Intakes (DRIs): Estimated Average Requirements" (PDF). United States National Academy of Sciences. Retrieved January 12, 2013.

- ^ Milton K (September 2003). "Micronutrient intakes of wild primates: are humans different?". Comp. Biochem. Physiol., Part a Mol. Integr. Physiol. 136 (1): 47–59. doi:10.1016/S1095-6433(03)00084-9. PMID 14527629.

- ^ "Linus Pauling Vindicated; Researchers Claim RDA For vitamin C is Flawed" (Press release). Knowledge of Health. July 6, 2004. Retrieved March 17, 2014.

- ^ World Health Organization (2004). "Chapter 7: Vitamin C". Vitamin and Mineral Requirements in Human Nutrition, Second Edition. Geneva: World Health Organization. ISBN 92-4-154612-3.

{{cite book}}:|access-date=requires|url=(help); External link in|chapterurl=|chapterurl=ignored (|chapter-url=suggested) (help) - ^ "Commission Directive 2008/100/EC of 28 October 2008 amending Council Directive 90/496/EEC on nutrition labelling for foodstuffs as regards recommended daily allowances, energy conversion factors and definitions". The Commission of the European Communities.

- ^ "Vitamin C". Natural Health Product Monograph. Health Canada.

- ^ Shibata K, Fukuwatari T, Imai E, Hayakawa T, Watanabe F, Takimoto H, Watanabe T, Umegaki K (January 2012). "Dietary Reference Intakes for Japanese 2010: Water-Soluble Vitamins". Journal of Nutritional Science and Vitaminology. 59 (Supplement): S67–S82. doi:10.3177/jnsv.59.S67.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Emadi-Konjin P, Verjee Z, Levin AV, Adeli K (2005). "Measurement of intracellular vitamin C levels in human lymphocytes by reverse phase high performance liquid chromatography (HPLC)". Clinical Biochemistry. 38 (5): 450–6. doi:10.1016/j.clinbiochem.2005.01.018. PMID 15820776.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Yamada H, Yamada K, Waki M, Umegaki K (2004). "Lymphocyte and Plasma Vitamin C Levels in Type 2 Diabetic Patients With and Without Diabetes Complications" (PDF). Diabetes Care. 27 (10): 2491–2. doi:10.2337/diacare.27.10.2491. PMID 15451922.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Pauling, Linus. (1976). Vitamin C, the Common Cold, and the Flu. San Francisco, CA: W.H. Freeman and Company.

- ^ "Toxicological evaluation of some food additives including anticaking agents, antimicrobials, antioxidants, emulsifiers and thickening agents". World Health Organization. July 4, 1973. Retrieved April 13, 2007.

- ^ Fleming DJ, Tucker KL, Jacques PF, Dallal GE, Wilson PW, Wood RJ (December 2002). "Dietary factors associated with the risk of high iron stores in the elderly Framingham Heart Study cohort". The American Journal of Clinical Nutrition. 76 (6): 1375–84. PMID 12450906.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Cook JD, Reddy MB (January 2001). "Effect of ascorbic acid intake on nonheme-iron absorption from a complete diet". The American Journal of Clinical Nutrition. 73 (1): 93–8. PMID 11124756.

- ^ Goodwin JS, Tangum MR (November 1998). "Battling quackery: attitudes about micronutrient supplements in American academic medicine". Archives of Internal Medicine. 158 (20): 2187–91. doi:10.1001/archinte.158.20.2187. PMID 9818798.

- ^ Massey LK, Liebman M, Kynast-Gales SA (July 2005). "Ascorbate increases human oxaluria and kidney stone risk". The Journal of Nutrition. 135 (7): 1673–7. PMID 15987848.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Thomas LD, Elinder CG, Tiselius HG, Wolk A, Akesson A (2013). "Ascorbic Acid Supplements and Kidney Stone Incidence Among Men: A Prospective Study". JAMA Intern Med. 173 (5): 1–2. doi:10.1001/jamainternmed.2013.2296. PMID 23381591.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Naidu KA (2003). "Vitamin C in human health and disease is still a mystery ? An overview" (PDF). J. Nutr. 2 (7): 7. doi:10.1186/1475-2891-2-7. PMC 201008. PMID 14498993.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: unflagged free DOI (link) - ^ Mashour S, Turner JF, Merrell R (August 2000). "Acute renal failure, oxalosis, and vitamin C supplementation: a case report and review of the literature". Chest. 118 (2): 561–3. doi:10.1378/chest.118.2.561. PMID 10936161.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Ovcharov R, Todorov S (1974). "[The effect of vitamin C on the estrus cycle and embryogenesis of rats]". Akusherstvo I Ginekologii͡a (in Bulgarian). 13 (3): 191–5. PMID 4467736.

- ^ Vobecky JS, Vobecky J, Shapcott D, Cloutier D, Lafond R, Blanchard R (1976). "Vitamins C and E in spontaneous abortion". International Journal for Vitamin and Nutrition Research. 46 (3): 291–6. PMID 988001.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Javert CT, Stander HJ (1943). "Plasma Vitamin C and Prothrombin Concentration in Pregnancy and in Threatened, Spontaneous, and Habitual Abortion". Surgery, Gynecology, and Obstetrics. 76: 115–122.

- ^ Gomez-Cabrera MC, Domenech E, Romagnoli M, Arduini A, Borras C, Pallardo FV, Sastre J, Viña J (January 2008). "Oral administration of vitamin C decreases muscle mitochondrial biogenesis and hampers training-induced adaptations in endurance performance". The American Journal of Clinical Nutrition. 87 (1): 142–9. PMID 18175748.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ "Cancer-Causing Compound Can Be Triggered By Vitamin C". March 13, 2007. Retrieved December 26, 2009.

- ^ a b c "Safety (MSDS) data for ascorbic acid". Oxford University. October 9, 2005. Retrieved February 21, 2007.

- ^ Wilson JX (2005). "Regulation of vitamin C transport". Annu. Rev. Nutr. 25: 105–25. doi:10.1146/annurev.nutr.25.050304.092647. PMID 16011461.

- ^ "The vitamin and mineral content is stable". Danish Veterinary and Food Administration. Archived from the original on October 14, 2011. Retrieved November 20, 2014.

- ^ "NDL/FNIC Food Composition Database Home Page". USDA Nutrient Data Laboratory, the Food and Nutrition Information Center and Information Systems Division of the National Agricultural Library. Retrieved November 20, 2014.

{{cite web}}: horizontal tab character in|title=at position 9 (help) - ^ a b "Natural food-Fruit Vitamin C Content". The Natural Food Hub. Retrieved March 7, 2007.

- ^ "Using local foods".

- ^ Prior LD, Eamus D, Duff GA (1997). "Seasonal Trends in Carbon Assimilation, Stomatal Conductance, Pre-dawn Leaf Water Potential and Growth in Terminalia ferdinandiana, a Deciduous Tree of Northern Australian Savannas". Australian Journal of Botany. 45 (1): 53–69. doi:10.1071/BT96065.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Brand JC, Rae C, McDonnell J, Lee A, Cherikoff V, Truswell AS (1987). "The nutritional composition of Australian aboriginal bushfoods. I". Food Technology in Australia. 35 (6): 293–296.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Justi KC, Visentainer JV, Evelázio de Souza N, Matsushita M (December 2000). "Nutritional composition and vitamin C stability in stored camu-camu (Myrciaria dubia) pulp". Arch Latinoam Nutr. 50 (4): 405–8. PMID 11464674.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Vendramini AL, Trugo LC (2000). "Chemical composition of acerola fruit (Malpighia punicifolia L.) at three stages of maturity". Food Chemistry. 71 (2): 195–198. doi:10.1016/S0308-8146(00)00152-7.

- ^ Poole KE, Loveridge N, Barker PJ, Halsall DJ, Rose C, Reeve J, Warburton EA (January 2006). "Reduced vitamin D in acute stroke". Stroke. 37 (1): 243–5. doi:10.1161/01.STR.0000195184.24297.c1. PMID 16322500.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ "Nutrient data: Guavas, common, raw". National Nutrient Database for Standard Reference Release 25. United States Department of Agriculture.

- ^ "Nutrient data: Persimmons, native, raw". National Nutrient Database for Standard Reference Release 25. United States Department of Agriculture.

- ^ "Nutrient data: 'Tomatoes, red, ripe, raw, year round average". National Nutrient Database for Standard Reference Release 25. United States Department of Agriculture.

- ^ "09038, Avocados, raw, California". National Nutrient Database for Standard Reference, Release 26. United States Department of Agriculture, Agricultural Research Service. Retrieved August 14, 2014.

- ^ "Nutrient data: Onion". National Nutrient Database for Standard Reference Release 25. United States Department of Agriculture.

- ^ "Nutrient data: Horned melon (Kiwano)". National Nutrient Database for Standard Reference Release 25. United States Department of Agriculture.

- ^ Nutrient Data Laboratory (2010). "USDA National Nutrient Database for Standard Reference, Release 23". United States Department of Agriculture Research Service. Retrieved 2011.