Patroclus

This article needs attention from an expert in Classical Greece and Rome. Please add a reason or a talk parameter to this template to explain the issue with the article. (April 2016) |

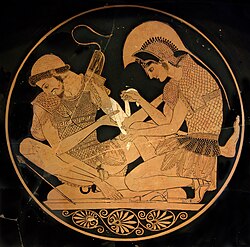

In Greek mythology, as recorded in Homer's Iliad, Patroklos (/pəˈtroʊkləs, pəˈtrɒkləs/; Ancient Greek: Πάτροκλος, romanized: Patroklos, lit. 'glory of the father') was the son of Menoetius, grandson of Actor, King of Opus, and Achilleus's beloved comrade and brother-in-arms.

Patroklos's genealogy

This section possibly contains original research. (November 2015) |

Menoetii and Philomelae are listed as the parents of Patroklos according to Hyginus.[1] Homer also references Menoitios as the one who gave Patroklos to Peleus. [2]

Menoetius was a son of Actor, King of Opus in Locris by Aegina. Aegina was a daughter of Asopus and mother of Aeacus by Zeus. Aeacus was father of Peleus, Telamon and Phocus.

Actor was a son of Deioneus, King of Phocis and Diomede. His paternal grandparents were Aeolus of Thessaly and Enarete. His maternal grandparents were Xuthus and Creusa, daughter of Erechtheus and Praxithea.

Life before the Trojan War

In his youth, Patroklos accidentally killed his friend, Clysonymus, during an argument over a game of dice. His father fled with Patroklos into exile to evade revenge, and they took shelter at the palace of their kinsman King Peleus of Phthia, where Patroklos was educated together with Peleus's son Achilleus.[3] Peleus sent the boys to live in the wilderness and be raised by Chiron, the cave-dwelling wise King of the Centaurs.

He is listed among the unsuccessful suitors of Helen,[3] all of whom took a solemn oath to defend the chosen husband against whoever should quarrel with him. At about that time Patroklos killed Las, founder of a namesake city near Gytheio, Laconia, according to Pausanias the geographer. Pausanias reported that the killing was alternatively attributed to Achilleus. However, Achilleus was not otherwise said ever to have visited Peloponnesos.

Trojan War activities

This section has multiple issues. Please help improve it or discuss these issues on the talk page. (Learn how and when to remove these template messages)

|

According to the Iliad, when the tide of war had turned against the Greeks and the Trojans were threatening their ships, Patroklos convinced Achilleus to let him lead the Myrmidons into combat. Achilleus consents, giving him the armor he had received from his father, Peleus, so that he might impersonate the feared Achilleus.[4] Patroklos pursued the Trojans all the way back to the gates of Troy and extinguishes the fire raging among the ships,[3] and in so doing he defied Achilleus's order to break off combat once the ships were saved. Patroklos killed many Trojans and allies, including the Lycian hero Sarpedon (the son of Zeus[5]) and Cebriones (the chariot driver of Hector and illegitimate son of Priam). Patroklos was stunned by Apollo, wounded by Euphorbos, and finished off by Hector, pierced by his spear.[6] At the time of his death, Patroklos had killed 53 enemy soldiers.[7][full citation needed][non-primary source needed] After retrieving his body, which had been stripped of armor by Hector and protected on the field by Menelaus and Ajax,[6] the enraged Achilleus returned to battle and avenged his companion's death by killing Hector. Achilleus then desecrated Hector's body by dragging it behind his chariot instead of allowing the Trojans to honorably dispose of it by burning it. Achilleus's grief was great, and for some time, he refused to dispose of Patroklos's body, but he was persuaded to do so by an apparition of Patroklos, who told Achilleus he could not enter Hades without a proper cremation. Achilleus sheared off his hair and sacrificed horses, dogs, and 12 Trojan captives before placing Patroklos's body on the funeral pyre.

Achilleus then organized an athletic competition to honor his dead companion, which included a chariot race (won by Diomedes), boxing (won by Epeios), wrestling (a draw between Telamonian Ajax and Odysseus), a foot race (won by Odysseus), a duel (a draw between Ajax and Diomedes), a discus throw (won by Polypoites), an archery contest (won by Meriones), and a javelin throw (won by Agamemnon, unopposed).

Relationship to Achilleus

Achilleus and Patroklos grew up together after Menoitios gave Patroklos to Achilleus' father, Peleus. During this time, Peleus named Patroklos one of Achilleus' "henchmen".[8] While Homer's Iliad never once explicitly stated that Achilleus and his close friend Patroklos were lovers, this concept was asserted by some later authors.[9][10][11] Aeschines asserts that there was no need to explicitly state the relationship as a romantic one,[11] for such "is manifest to such of his hearers as are educated men."[12] Later Greek writings such as Plato's Symposium, the relationship between Patroklos and Achilleus is discussed as a model of romantic love.[13] However, Xenophon, in his Symposium, had Socrates argue that it was inaccurate to label their relationship as romantic. Nevertheless, their relationship is said to have inspired Alexander the Great in his close relationship with his companion Hephaestion.[9][14] After Patroklos killed Clysonymus, Patroklos and his father fled to Peleus palace. Patroklos then grew up with Achilleus. Their relationship was so strong that it was as if they were more than brothers. However, Achilleus was much younger than Patroklos.[13] This reinforces Dowden's explanation of the relationship between an eromenos, a youth in transition, and an erastes, an older male although having recently made the same transition.[15] Dowden also notes the common occurrence of such relationships as a form of initiation.[16]

Peleus made Patroklos Achilleus' squire to allow Patroklos a right to fight with Achilleus in the Trojan War [17]

Burial and later reports

The funeral of Patroklos is described in the Iliad;[18] Patroklos is cremated on a funeral pyre, and his bones are collected into a golden urn in two layers of fat. The ashes of Achilleus were said to have been buried in the golden urn along with those of Patroklos by the Hellespont.[4]

Alexander the Great, who modeled himself after Achilleus and claimed descent from him via his mother Olympias,[19] visited the grave with his own male lover Hephaestion, who crowned Patroklos' tomb while Alexander placed a copy of the Iliad, annotated by Aristotle, in a casket associated with Achilleus' tomb.[14] Alexander became haunted by thoughts of his own doom following the death of Hephaestion, seeing an analogy between Achilleus' death shortly after that of his lover with his own death following that of his lover. Taking heavily to wine, Alexander died shortly thereafter.[20]

In Homer's Odyssey, Odysseus meets Achilleus in Hades, accompanied by Patroklos, Telamonian Ajax and Antilochus.[21]

Further reading

- Evslin, Bernard (2006). Gods, Demigods and Demons. London, ENG: I. Tauris.

- Michelakis, Pantelis (2007). Achilles in Greek Tragedy. Cambridge, ENG: Cambridge University Press.

- Kerenyi, Karl (1959). The Heroes of the Greeks. London, ENG: Thames and Hudson. pp. 57–61, et passim.

- Sergent, Bernard (1986). Homosexuality in Greek Myth. Boston, MA, USA: Beacon Press.

References

- ^ Hyginus. Fabulae.

- ^ Homer. The Iliad of Homer. Chicago: The University of Chicago Press. p. 474.

- ^ a b c Smith, William (1870). Dictionary of Greek and Roman biography and mythology. Vol. 3. Boston, Little. p. 140.

- ^ a b Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). . Encyclopædia Britannica (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press.

- ^ Lattimore, Richmond (2011). The Iliad of Homer. Chicago: The University of Chicago Press. p. 363 l. 460. ISBN 9780226470498.

- ^ a b Bulfinch, Thomas (1985). The Golden Age. London: Bracken Books. p. 272.

- ^ Hyginus, Fabulae 114.[full citation needed] [non-primary source needed]

- ^ Homer. The Iliad of Homer. Chicago: The University of Chicago Press. p. 474.

- ^ a b Martin, Thomas R. (2012). Alexander the Great: The Story of an Ancient Life. Cambridge, ENG: Cambridge University Press. pp. 99–100. ISBN 0521148448.

[See next reference for a relevant quotation.]

- ^ As Martin (2012), op. cit., argues (see preceding footnote), "The ancient sources do not report, however, what modern scholars have asserted: that Alexander and his very close friend Hephaestion were lovers. Achilles and his equally close friend Patroclus provided the legendary model for this friendship, but Homer in the Iliad never suggested that they had sex with each other. (That came from later authors.) If Alexander and Hephaestion did have a sexual relationship, it would have been transgressive by majority Greek standards…" (p. 99f).

- ^ a b Boswell, John (1980). Christianity, Social Tolerance, and Homosexuality. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. p. 47.

- ^ Aeschines (1958). The Speeches: Against Telemarchus, On the Embassy, Against Ctesiphon. Translated by Charles Darwin Adams. London: Harvard University Press. p. 115.

- ^ a b Plato (1987). The Symposium. Translated by Walter Hamilton. Penguin Books. pp. 44–45.

- ^ a b Fox, Robin Lane (2005). The Classical World. Penguin Books. p. 235.

- ^ Dowden, Ken (1992). The Uses of Greek Mythology. London: Routledge. p. 112.

- ^ Dowden, Ken (1992). The Uses of Greek Mythology. London: Routledge. p. 114.

- ^ Colum, Padraic (1918). The Children's Homer. Aladin Paperbacks.

- ^ Iliad, book XXIII.[full citation needed] [non-primary source needed]

- ^ Durant, Will (1939). The Life of Greece. Vol. 2. New York: Simon and Schuster. p. 538.

{{cite book}}:|work=ignored (help) - ^ Durant, Will (1939). The Life of Greece. Vol. 2. New York: Simon and Schuster. p. 551.

{{cite book}}:|work=ignored (help) - ^ Homer (1991). The Odyssey. Translated by E.V. Rieu. Penguin Books. p. 355. ISBN 0-14-044556-0.

External links

Media related to Patroclus at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Patroclus at Wikimedia Commons

| Achilleus and Patroklos myths as told by story tellers |

|---|

| Bibliography of reconstruction: Homer Iliad, 9.308, 16.2, 11.780, 23.54 (700 BC); Pindar Olympian Odes, IX (476 BC); Aeschylus Myrmidons, F135-36 (495 BC); Euripides Iphigenia in Aulis, (405 BC); Plato Symposium, 179e (388-367 BC); Statius Achilleid, 161, 174, 182 (96 AD) |