History of Solidarity

The history of Solidarity begins in August 1980 at the Gdańsk Shipyards, where Lech Wałęsa and others formed Solidarity (Polish: Solidarność), a Polish non-governmental trade union. In the early 1980s, it became the first independent labor union in a Soviet-bloc country. Solidarity gave rise to a broad anti-communist social movement that, at its height, united some 10 million members. It advocated nonviolence in its members' activities. Poland's communist government attempted to destroy the union by instituting martial law in 1981, followed by several years of repressions, but in the end was forced to begin negotiating with the union.

Solidarity's survival meant a break in the hard-line stance of the communist Polish United Workers' Party, and was an unprecedented event not only for Poland, a satellite of the USSR ruled by a one-party communist regime, but for the whole of the Eastern bloc. Solidarity's influence led to the Revolutions of 1989 (the "Autumn of Nations") and to the spread of anti-communist ideas and movements throughout the countries of the Eastern Bloc, sapping their communist governments. In Poland, the Roundtable Talks between the weakened government and the Solidarity-led opposition resulted in semi-free elections in 1989. By the end of August 1989, a Solidarity-led coalition government was formed, and in December 1990 Wałęsa was elected president. This was soon followed by the dismantling of the communist governmental system and by Poland's transformation into a modern democratic state.

In the 1990s, Solidarity's influence on Poland's political scene waned. A political arm of the "Solidarity" movement, Solidarity Electoral Action (AWS), was founded in 1996 and would win the Polish parliamentary elections in 1997, only to lose the subsequent, 2001 elections.

Currently Solidarity has little political influence and is more active as a traditional trade union.

Pre-1980 roots

In the 1970s and '80s, the initial success of Solidarity in particular, and of dissident movements in general, was fed by a deepening crisis within Soviet-style societies brought about by declining morale, worsening economic conditions (a shortage economy), and the growing stresses of the Cold War.[1] After a brief period of economic boom, from 1975 the policies of the Polish government, led by Party First Secretary Edward Gierek, precipitated a slide into increasing depression, as foreign debt mounted.[2] In June 1976, the first workers' strikes took place, involving violent incidents at factories in Radom and Ursus.[3] When these incidents were quelled by the government, the worker's movement received support from intellectual dissidents, many of them associated with the Committee for Defense of the Workers (Polish: Komitet Obrony Robotników, abbreviated KOR), formed in 1976.[1][4] The following year, KOR was renamed the Committee for Social Self-defence (KSS-KOR).

On October 16, 1978, the Bishop of Kraków, Karol Wojtyła, was elected Pope John Paul II. A year later, during his first pilgrimage to Poland, his masses were attended by millions of his countrymen. The Pope called for the respecting of national and religious traditions and advocated for freedom and human rights, while denouncing violence. To many Poles, he represented a spiritual and moral force that could be set against brute material forces; he was a bellwether of change, and became an important symbol—and supporter—of changes to come.[5][6] He would later (December 30, 1987) address the concept of solidarity in his encyclical, Sollicitudo Rei Socialis.

Early strikes (1980-1981)

The labor strikes did not just occur because of problems that emerged shortly before the unrest, but due to the difficulties of the government and the economy for over ten years. In July of 1980, the government of Edward Gierek, facing an economic crisis, decided to raise prices while slowing the growth of wages. A wave of strikes and factory occupations began at once.[1] Although the strike movement had no coordinating centre, the workers had developed an information network by which they spread news of their struggles. A group of ‘dissidents’, the Committee for the Defence of Workers (KOR), set up originally in 1976 to organise aid for victimised workers, drew around them small circles of working class militants in major industrial centres.[1] At the Lenin Shipyard in Gdańsk, workers were outraged at the sacking of Anna Walentynowicz, a popular crane operator and well-known activist who became a spark that pushed them into action.[1][7]

On August 14 , the shipyard workers began their strike, organized by the Free Trade Unions of the Coast (Wolne Związki Zawodowe Wybrzeża).[8] The workers were led by electrician Lech Wałęsa, a former shipyard worker who had been dismissed in 1976, and who arrived at the shipyard late in the morning of August 14.[1] The strike committee demanded the rehiring of Anna Walentynowicz and Lech Wałęsa, as well as respect for worker's rights and other social issues. In addition, they called for the raising of a monument to the casualties of 1970 and legalization of independent trade unions.[9]

Government used censorship and the official media spoke little about sporadic disturbances in work in Gdańsk; as a further precaution soon all phone connections from the coast to the rest of Poland were cut.[1] Nonetheless the governement failed to contain the information: a spreading wave of samizdat (bibuła)[10] such as Robotnik and grapevine gossip, along with the transmissions of Radio Free Europe penetrating the Iron Curtain,[11] ensured that the ideas of the emerging Solidarity movement spread very quickly.

On August 16 delegations from other strike committees arrived at the shipyard.[1] The members of those delegations (Bogdan Lis, Andrzej Gwiazda and others) together with the strikers inside the shiplayer agreed on the creation of the Inter-Enterprise Strike Committee (Międzyzakładowy Komitet Strajkowy, MKS).[1]. On the August 17, a priest, Henryk Jankowski performed a mass outside the gate of the shipyard, on which 21 demands of MKS were put. No longer concerned only with immediate local issues, the list began with the demand for new, independent trade unions. It went on to call for relaxation of censorship, the right to strike, new rights for the church, the freeing of political prisoners and improvements in the health service.[1] Next day a delegation of intelligentsia from KOR arrived, declaring their assistance with negotiations. Among the members of the KOR delegation was Tadeusz Mazowiecki. A bibuła news-sheet, Solidarnosc, produced on the shipyard’s printing press with the assistance of KOR members, reached a print run of 30,000 copies daily.[1] In the meantime, Mury (Walls) protest song of Jacek Kaczmarski became very popular among the workers.[12]

On August 18 the Szczecin Shipyard joined the strike, under the leadership of Marian Jurczyk. The strike wave spread along the coast, closing the ports and bringing the economy to a halt. With the assistance of the activists from KOR and the support of many intellectuals, the workers occupying the various factories, mines and shipyards across Poland came together. Within days, over 200 factories and enterprises had joined the strike committee.[1][7] By August 21 most of Poland was affected by the strikes, from shipyards of the coastal cities to the mines in Silesian Upper Silesian Industrial Area. More and more new unions were formed and joined the federation. By the end of the strike wave, MKS represented hundreds of factories from all over Poland.

Due to the popular support of the citizens and other striking groups, as well as international support and media coverage, the Gdańsk workers held out until the government gave in to their demands. On August 21 a Governmental Commission (Komisja Rządowa) with Mieczysław Jagielski arrived in Gdańsk, and another one with Kazimierz Barcikowski was dispatched to Szczecin. On 30 and 31 August, and September 3 the representatives of the workers and the government signed an agreement, formalizing the acceptance of many of the workers demand, including their right to strike.[1] This agreement came to be known as the August or Gdańsk agreement (Porozumienia sierpniowe).[7] The program, although concerned with trade union matters, allowed citizens to bring democratic changes within the communist political structure and was universally regarded as the first step towards dismantling the Party monopoly. [13] The main concern of the workers was the establishment of a trade union independent of communist party control and the legal right to strike. In creating these new groups, there would be a clear representation of the workers’ needs.[14] Another consequence of the Gdańsk Agreement was the replacement of Edward Gierek by Stanisław Kania in September 1980.[15]

Encouraged by the success of the August strike, on the September 17, the representatives of Polish workers, including Lech Wałęsa, formed a nationwide trade union, Solidarity (Niezależny Samorządny Związek Zawodowy (NSZZ) "Solidarność").[1][7][16] It was the first independent labour union in a country belonging to the Soviet bloc.[17] Name was proposed by Karol Modzelewski, and the famous logo with the was designed by Jerzy Janiszewski, designer of many Solidarity-related posters. The legislature, known as Convention of the Delegates (Zjazd Delegatow) was given top powers, executive branch was the National Coordinating Commission (Krajowa Komisja Porozumiewawcza), later renamed to National Commission (Komisja Krajowa). The Union had a regional structure, with 38 regions (region) and two districts (okręg).[16] On December 16, 1980 the Monument to fallen Shipyard Workers was unveiled. On January 15, 1981 a delegation from Solidarity, including Lech Wałęsa, met Pope John Paul II in Rome. Between September 5 and 10 and September 26 to October 7 the first national congress of Solidarity was held, and Lech Wałęsa was elected its president.[18]

In the meantime Solidarity was transforming from a trade union into a social movement.[19] Over the next 500 days following the Gdańsk Agreement, 9 to 10 million workers, intellectuals and students joined it or its suborganizations.[1] Those suborganizations organized various groups: for example, there was the Independent Students Union (Niezależne Zrzeszenie Studentów), created in September 1980, Independent Farmers' Trade Union (NSZZ Rolników Indywidualnych "Solidarność"), created in May 1981) and Independent Craftsmen Trade Union).[16] It was the first and only recorded time in the history that a quarter of a country's population (about 80% of total Polish workforce) have voluntarily joined a single organization.[1][16] "History has taught us that there is no bread without freedom," the Solidarity programme stated a year later. "What we had in mind were not only bread, butter and sausage but also justice, democracy, truth, legality, human dignity, freedom of convictions, and the repair of the republic."[7]

Using strikes and other protest actions, Solidarity sought to force a change in the governmental policies. At the same time it was careful to never use force or violence, to avoid giving the government any excuse to bring the security forces into play.[20][21] After over 27 Solidarity members in Bydgoszcz, including Jan Rulewski, were beaten up on March 19, a 4-hour strike on March 27, involving over half a million people paralyzed the entire country.[1] This strike was the largest strike in the history of the Eastern bloc[22] and it forced the government to promise that the investigation into the beatings will be carried out.[1] This concession, and Wałęsa agreement to postpone further planned strike, became somewhat of a setback to the movement, as in the lull period the wave of euphoria that swept the Polish society became somewhat subdued.[1] Nonetheless the Communist Party of Poland - Polish United Workers Party (PZPR) lost its total control over the society.[13] Yet while Solidarity was ready to take up negotiations with the government,[23] the Polish communists were unsure what to do, issuing empty declarations and biding their time.[15] In the background of deteriorating communist shortage economy and unwillingness to seriously negotiate with Solidarity, it became increasingly clear that the Communist government would eventually have to suppress the movement as the only way out of the impasse, or face a truly revolutionary situation. The atmosphere was increasingly tense, with increasing number of uncoordinated strikes being the responce of various local chapters to worsening economic situation.[1] On December 3 the Solidarity declared that a 24-hours strike would be held if the government was granted additional prerogatives for suppressing dissent, and that a general strike would be declared if those prerogatives entered into use.

Martial law (1981-1983)

After Gdańsk Agreement the Polish government was under increasing pressure from Moscow to take action and strengthen its position. Stanisław Kania was viewed by Moscow as too independent, and so on October 18, 1981, the Central Committee of the Party put him in minority. Kania lost his post as general secretary, being replaced by Prime Minister (and Minister of Defence) Gen. Wojciech Jaruzelski who adopted a strong-arm policy.[23]

On December 13, 1981, the government leader Wojciech Jaruzelski started a crack-down on Solidarity, declaring martial law and creation of Military Council of National Salvation (Wojskowa Rada Ocalenia Narodowego, WRON). Solidarity's leaders gathered at Gdańsk were arrested and isolated in facilities guarded by Służba Bezpieczeństwa, and about five thousand of Solidarity's supporters were arrested in the middle of the night.[1][16] Censorship was expanded, and military forces appeared on the streets.[23] There were a couple of hundred strikes and occupations, chiefly in the largest plants and in several of the Silesian coalmines, but they were broken by paramilitary riot police ZOMO. One of the largest demonstrations on December 16, 1981, took place at Wujek Coal Mine, there government forces opened fire on the demonstrators, killing 9[1] and seriously injuring 22.[18] Next day during protests in Gdańsk government forces also fired at the demonstrators, killing 1 and injuring 2. By the 28th of December strikes had ceased, and Solidarity appeared crippled. Solidarity was delegalized and banned on October 8, 1982.[24]

The international community from outside Iron Curtain condemned Jaruzelski's action and declared support for Solidarity.[16] US President Ronald Reagan imposed economic sanctions on Poland, which eventually would force the Polish government into liberalizing their policies.[25] Meanwhile CIA[26] together with Catholic Church and various Western trade unions like AFL-CIO provided funds, equipment and advice for the underground Solidarity.[27] Political alliance of Reagan and Pope would prove important to the future of Solidarity.[27] Polish public also supported the remains of the Solidarity; one of the largest demonstrations of support for Solidarity became religious ceremonies, such as masses held by priests like Jerzy Popiełuszko.[28]

Martial Law was formally lifted in July, 1983, though many heightened controls on civil liberties and political life, as well as food rationing, remained in place through the mid- to late 1980s.[29]

Underground Solidarity (1982-1988)

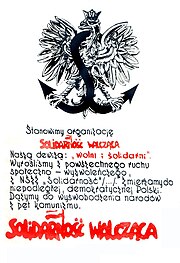

Almost immediately after the legal Solidarity leadership was arrested, underground structures begun to arise.[16] On April 12, Radio Solidarity begun broadcasting.[18] On April 22, 1982 Zbigniew Bujak, Bogdan Lis, Władysław Frasyniuk and Władysław Hardek created the Interim Coordinating Commission (Tymczasowa Komisja Koordynacyjna), which served as an underground leadership of Solidarity.[30] On 6 May another underground Solidarity organisation (Regional Coordinating Commission of NSSZ "S" - Regionalna Komisja Koordynacyjna NSZZ "S") was created by Bogdan Borusewicz, Aleksander Hall, Stanisław Jarosz, Bogdan Lis and Marian Świtek.[18] In June 1982 the Fighting Solidarity (Solidarność Walcząca) organization was created. [30][31]

Throughout the mid-1980s, Solidarity persisted solely as an underground organization.[32] All of its activists were pursued by Służba Bezpieczeństwa, but still managed to strike back: on May 1, 1982 a series of anti-government protests gathered thousands of people (several dozens of thousands in Gdańsk).[18] The protests took place again on May 3, during the festivities celebrating the Polish Constitution of May 3. More strikes took place in Gdańsk from October 11 to 13.[18]

Lech Wałesa was released on November 14, 1982.[16] However on December 9 the SB carried out a large anti-Solidarity action, arresting over 10,000 Solidarity activists. On December 27 all of Solidarity's assets were transferred to the official, pro-government trade union All-Polish Agreement of Trade Unions (Ogólnopolskie Porozumienie Związków Zawodowych, OPZZ). Yet Solidarity was far from broken: by early 1983 its underground structure had over 70,000 members, who among other activities were publishing over 500 underground newspapers.[33]

Martial law was lifted on July 22, 1983, and an amnesty was given to many imprisoned members of the trade union, who were released from imprisonment.[32] On October 5, Lech Wałęsa received a Nobel Peace Prize.[34] However the Polish government still refused to issue him a passport and allow him to leave the country; the award was received in his name by his wife.[35] It was later revealed that SB had prepared fake documents accusing Wałęsa of various immoral and illegal activities - these were given to the Nobel committee in an attempt to derail the Wałęsa nomination.[36]

On October 19, 1984 three agents of the Ministry of Internal Security murdered a popular pro-Solidarity priest, Jerzy Popiełuszko.[37] As the truth about the murder was revealed, thousands of people declared solidarity with the priest by attending his funeral on November 3, 1984. The government attempted to calm the situation by releasing thousands of political prisoners;[34] however a year later a new wave of arrests followed.[16] Frasyniuk, Lis and Adam Michnik, members of the underground "S" were arrested on February 13, 1985 and in a show trial sentenced to several years of imprisonment.[18][38]

On March 11, 1985, the Soviet Union found itself under the rule of Mikhail Gorbachev, a leader representing a new generation of Soviet party members. The worsening economic situation in the entire Eastern Bloc, including the Soviet Union, as well as other factors, forced Gorbachev to carry out several reforms, not only in the field of economics (Uskoreniye), but also in political and social structure (Glasnost and Perestroika).[39] His policies soon caused a mirror shift in the policies of Soviet satellites, such as the People's Republic of Poland.[34] On September 11, 1986, 225 political prisoners in Poland were released; last of those connected with Solidarity and arrested in the previous years.[34] On September 30 Lech Wałęsa created the first public and legal Solidarity structure since the declaration of martial law, the Temporary Council of NSZZ Solidarność (Tymczasowa Rada NSZZ Solidarność), with Bogdan Borusewicz, Zbigniew Bujak, Władysław Frasyniuk, Tadeusz Jedynak, Bogdan Lis, Janusz Pałubicki and Józef Pinior; soon afterwards it was admitted to the International Confederation of Free Trade Unions.[16] Many local Solidarity chapters then revealed themselves throughout Poland, and on October 25, 1987 the National Executive Committee of NSZZ Solidarność (Krajowa Komisja Wykonawcza NSZZ Solidarność) was created.

Nonetheless the Solidarity members and activists were still persecuted and discriminated against, albeit to a lesser extent than during the early 1980s.[18] There was a deepening divide between the Wałęsa faction, which wanted to negotiate with the government, and a more radical faction planning for an anti-communist revolution, like Fighting Solidarity. [30][40][41]

Fall of the U.S.S.R. (1988-1989)

Solidarity Citizens' Committee election poster by Tomasz Sarnecki.

By 1988 the economy was in a worse condition than 8 years earlier. International sanctions combined with the government's unwillingness to reforms intensified the old problems.[34][25] Inefficient national enterprises in planned economy wasted labor and resources, producing substandard goods for which there was little demand. Polish exports were low, both because of the sanctions and because its goods were as unattractive abroad as at home; foreign debt and inflation were growing. There was no funds to modernise the factories, and promised 'market socialism' was in fact a shortage economy, characterized by long queues and empty shelves.[42] Reforms of Jaruzelski and Mieczysław Rakowski came too late and were insufficient, especially as changes in the Soviet Union increased social expectations that the change must come, and the Soviets seized their efforts to prop up the failing regime in Poland. [34][43]

In February, the government increased food prices by 40%.[34] On April 21, 1988 a new wave of strikes hit the country.[34] On May 2 workers from Gdańsk Shipyard went on strike.[18] That strike was broken by the government from May 5 to 10, but only temporarily: a new strike took place in "July Manifest" mine in Jastrzębie Zdrój on August 15.[18] The strike spread to many other mines by August 20, and on 22 the Gdańsk Shipyard joined the strike as well.[18] Polish communist government at that time decided to negotiate.[34][16]

On August 26, Czesław Kiszczak, Minister of Internal Affairs, declared on television that the government was willing to negotiate, and 5 days later he met with Wałęsa. The strikes ended on the following day, and on October 30, during a television debate between Wałęsa and Alfred Miodowicz (the leader of pro-government trade union, the All-Polish Agreement of Trade Unions (Ogólnopolskie Porozumienie Związków Zawodowych, OPZZ) Wałęsa scored a public relations victory.[34]

On December 18, a 100-member strong Citizen's Committee (Komitet Obywatelski) was created within NSZZ Solidarność. It was divided into several sections, each responsible for presenting a specific aspect of opposition demands to the government. Some members of the opposition, supported by Wałęsa and majority of Solidarity leaders, supported the negotiations, although there was some opposition from the minority which wanted a counter-communist revolution. Nonetheless, Solidarity under Wałęsa's leadership decided to pursue a peaceful solution, and the pro-violence faction never had any significant power, nor had it taken any actions.[20][21]

On January 27, 1989, during a meeting between Wałęsa and Kiszczak, the list of members of the main negotiations teams was determined. The negotiations that started on February 6 would be known as the Polish Round Table Agreement.[44] Among its 56 participants were: 20 from "S", 6 from OPZZ, 14 from PZPR, 14 'independent authorities' and two priests. The Polish Round Table Talks took place in Warsaw, Poland, from February 6 to April 4, 1989. The Polish Communists, led by Gen. Jaruzelski, hoped to co-opt prominent opposition leaders into the ruling group without making major changes in the structure of the political power. Solidarity itself, while hopeful, did not anticipate a major change. In reality, the talks would radically alter the shape of the Polish government and society.[44][43]

Solidarity was legalized on April 17, 1989, soon its membership reached 1,5 million.[18][16] The Solidarity Citizens' Committee (Komitet Obywatelski "Solidarność") was also allowed to participate in the upcoming elections. Election law allowed Solidarity to put forward candidates for only 35% of the seats in Sejm, but there were no restrictions for the Senate of Poland candidates.[45]Agitation and propaganda continued legally to the voting day. Despite being short on resources, Solidarity managed to carry out an electoral campaign.[45][44] On May 8, the first issue of a new, pro-Solidarity newspaper Gazeta Wyborcza (Election Gazette) was published.[46] Posters with Lech Wałęsa supporting various candidates could be seen throughout the country.

Pre-election public opinion polls promised victory to the Polish communists.[44] Thus the total defeat of PZPR and its satellite parties came as a surprise to everyone involved: after the first round of elections it became evident that Solidarity fared extremely well,[43] capturing 160 out of 161 contested Sejm seats, and 92 out of 100 Senate ones. After the second turn, it had won virtually every single seat - all 161 in Sejm, and 99 in Senate.[45] The new Contract Sejm, named after the agreement reached by the communist party and the Solidarity movement during the Polish Round Table Agreement, would be dominated by Solidarity. As agreed beforehand, Wojciech Jaruzelski was elected the president.[45][43] However, the communist candidate for Prime Minister, Czesław Kiszczak, replacing Mieczysław Rakowski,[43] failed to gain enough support to form a government.[47][45]

On June 23, the Citizen's Parliamentary Club "Solidarity" (Obywatelski Klub Parlamentarny "Solidarność") led by Bronisław Geremek was formed.[43] That club formed a coalition with two former satellite parties of PZPR: ZSL and SD, which chose this time to 'rebel' against PZPR, which found itself in minority.[47] On August 24, Sejm chose Tadeusz Mazowiecki, a Solidarity representative, to become a Prime Minister of Poland.[43][45]Cite error: A <ref> tag is missing the closing </ref> (see the help page). By the end of August a Solidarity-led coalition government was formed.

Fall of communism (1989) to the present

The fall of the communist regime marked a new chapter in the history of Poland and in the history of Solidarity. Having defeated the communist government, Solidarity found itself in a role it was much less prepared for: that of a political party and soon Solidarity popularity begun eroding.[16][48] Conflicts between various factions inside Solidarity intensified.[16][49] Wałęsa was elected the chairman of Solidarity, but his support could be seen to be crumbling, and one of his main opponents, Władysław Frasyniuk, withdrew from elections altogether. In September Wałęsa declared that Gazeta Wyborcza had no right to use the Solidarity logo. Later that month he declared his intentions to be a contestant for the Polish presidential election, 1990. In December Wałęsa was elected president.[16] He resigned from his post in Solidarity and become the first President of Poland elected by popular vote. These elections where anti-communist candidates won a striking victory started a series of peaceful anti-communist revolutions in Central and Eastern Europe[50][21][51] that eventually culminated in the fall of communism.[52][53]

Next year, in February, Marian Krzaklewski was elected the leader of Solidarity.[16] Despite Wałęsa being the president of Poland, his visions and that of the new Solidarity leadership were diverging. Far from supporting him, Solidarity was becoming increasingly critical of the government and decided to create its own political party for the Polish parliamentary election, 1991.[54] That election was characterized by a very high number of competing parties, many claiming the legacy of anti-communism, and the NSZZ "Solidarność" party gained only 5% of total vote. On January 13, 1992 Solidarity declared its first strike against the democratic government: a 1 hour strike against the proposed raise in prices of energy. Another, 2 hour strike took place on December 14. On May 19, 1993 deputies of Solidarity proposed a motion of no confidence for the government of prime minister Hanna Suchocka, which passed.[16] President Wałęsa did not accept the resignation of the prime minister and disbanded the parliament.

It was in the resulting Polish parliamentary election, 1993, that it became evident how much Solidarity's support had eroded in the past three years. Even though some Solidarity members tried to assume a more left-wing stance and distance themselves from the right-wing government, Solidarity was still identified with the latter. Thus it suffered from the increasing disillusionment of the population, as transition from communist to a capitalist system failed to generate instant wealth and raise living standards in Poland to those in the West, and the shock therapy (Balcerowicz's Plan) generated much opposition.[54][16] In the elections Solidarity received only 4,9%, 0,1% below the required 5% to enter the parliament (it still had 9 senators, 2 fewer then in the previous Senate of Poland), and the victorious party was the Democratic Left Alliance (Sojusz Lewicy Demokratycznej) - a post-communist left-wing party.[16]

Solidarity then joined forces with its past enemy, All-Polish Agreement of Trade Unions (OPZZ), and some of the protests were organized by both trade unions.[54] In the following year, Solidarity organised many strikes related to the situation of Polish mining industry. In 1995 a demonstration in front of the Polish parliament was broken by police (now known as Policja), using batons and water guns. Nonetheless Solidarity decided to support Lech Wałesa in the Polish presidential election, 1995. In a second major defeat for the Polish right-wing, the elections were won by a SLD candidate, Aleksander Kwaśniewski, who got 51.72% vote. Solidarity call for the new elections went unheeded, but the Polish Sejm still managed to pass a motion condemning the 1981 martial law (despite SLD voting against it). In the meantime, the left-wing OPZZ trade union had acquired 2,5 millions members, over twice as many as the contemporary Solidarity (with 1,3 millions).[54]

In June 1996 the Solidarity Electoral Action (Akcja Wyborcza Solidarność) was founded as a coalition of over 30 right-wing parties, uniting liberal, conservative and Christian democratic forces. As the society became disillusioned with the SLD and its allies, AWS was victorious in the Polish parliamentary election, 1997.[16] Jerzy Buzek became the new Prime Minister. However controversy over the reforms relating to domestic affairs, the entry to NATO in 1999]and the accession process to the European Union, combined with much fights with its political allies (Freedom Union (Unia Wolności)) and infighting within the party itself and corruption (the famous TKM slogan) eventually resulted in the loss of much public support.[16] AWS leader Marian Krzaklewski, lost in the Polish presidential election, 2000 and in Polish parliamentary election, 2001 AWS failed to elect a single deputy to the parliament.[16] After this defeat the union decided to distance itself from politics.[16]

Currently Solidarity has some 1.5 million members, but little political clout. Its mission statement declares that Solidarity, "basing its activities on Christian ethics and Catholic social teachings, works to protect workers' interests and to fulfill their material, social and cultural aspirations."[55]

References

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u v Colin Barker. "The rise of Solidarnosc". International Socialism, Issue: 108. Retrieved 2006-07-10.

- ^ Keith John Lepak, Prelude to Solidarity, Columbia University Press, 1989, ISBN 0231066082, Google Print, p.100

- ^ Barbara J. Falk, The Dilemmas of Dissidence in East-Central Europe: Citizen Intellectuals and Philosopher Kings, Central European University Press, 2003, ISBN 9639241393, Google Print, p.34

- ^ Falk, op.cit., Google Print, p.35

- ^ Weigel, George (2003). The Final Revolution: The Resistance Church and the Collapse of Communism (ebook). Oxford University Press US. pp. p. 136. ISBN 0-19-516664-7. Retrieved 2006-07-10.

{{cite book}}:|pages=has extra text (help); Cite has empty unknown parameters:|origmonth=,|origdate=, and|coauthors=(help); Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ George Weigel, Witness to Hope: The Biography of Pope John Paul II, HarperCollins, 2005, 0060732032, Google Print, p.292

- ^ a b c d e "The birth of Solidarity (1980)". BBC News. Retrieved 2006-07-10.

- ^ Michael Bernhard, Henryk Szlajfer, From The Polish Underground, Penn State Press, 2004, Google Print, p.405

- ^ William D Perdue, Paradox of Change: The Rise and Fall of Solidarity in the New Poland, Praeger/Greenwood, 1995, ISBN 0275952959, Google Print, p.39

- ^ Michael H. Bernhard, The Origins of Democratization in Poland, Columbia University Press, 1993, ISBN 023108093X, Google Print, p.149

- ^ G. R. Urban, Radio Free Europe and the Pursuit of Democracy: My War Within the Cold War, Yale University Press, ISBN 0300069219, Google Print, p.147

- ^ Yalta 2.0, Warsaw Voice, 31 August 2005, last accessed on 8 October 2006.

- ^ a b Norman Davies, God's Playground, , 2005, 0231128193, Google Print, p.483

- ^ Anna Seleny, The Political Economy of State-Society Relations in Hungary and Poland, Cambridge University Press, 2006, 052183564X, Google Print, p.100

- ^ a b Anna Seleny, op.cit., Google Print, p.115

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u v w Template:Pl icon Solidarność NSZZ in WIEM Encyklopedia. Last accessed on 10 October 2006

- ^ Solidarity, Encyclopedia Britannica.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l Template:Pl icon KALENDARIUM NSZZ „SOLIDARNOŚĆ” 1980-1989. Template:Pdf Last accessed on 15 October 2006

- ^ Bronisław Misztal, Poland after Solidarity: Social Movements Vs. the State, Transaction Publishers, 1985, ISBN 0887380492, Google Print, p.4

- ^ a b Paul Wehr, Guy Burgess, Heidi Burgess, ed. (1994). Justice Without Violence (ebook). Lynne Rienner Publishers. pp. p 28. ISBN 1-55587-491-6. Retrieved 2006-07-06.

{{cite book}}:|pages=has extra text (help); Cite has empty unknown parameters:|origmonth=,|origdate=, and|coauthors=(help); Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: editors list (link) - ^ a b c Cavanaugh-O'Keefe, John (2001). Emmanuel, Solidarity: God's Act, Our Response (ebook). Xlibris Corporation. pp. p 68. ISBN 0-7388-3864-0. Retrieved 2006-07-06.

{{cite book}}:|pages=has extra text (help); Cite has empty unknown parameters:|origdate=and|coauthors=(help); Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ MacEachin, Douglas J (2004). U.S. Intelligence and the Confrontation in Poland, 1980-1981 (ebook). Penn State Press. pp. p 120. ISBN 0-271-02528-X. Retrieved 2006-07-10.

{{cite book}}:|pages=has extra text (help); Cite has empty unknown parameters:|origmonth=,|origdate=, and|coauthors=(help); Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ a b c "Martial law (1981)". BBC News. Retrieved 2006-07-10.

- ^ Perdue, William D (1995). Paradox of Change: The Rise and Fall of Solidarity in the New Poland (ebook). Praeger/Greenwood. pp. p 9. ISBN 0-275-95295-9. Retrieved 2006-07-10.

{{cite book}}:|pages=has extra text (help); Cite has empty unknown parameters:|origmonth=,|origdate=, and|coauthors=(help); Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ a b Aryeh Neier, Taking Liberties: Four Decades in the Struggle for Rights, Public Affairs, 2003, ISBN 1891620827, Google Print, p.251

- ^ Schweizer, Peter (1996). Victory: The Reagan Administration's Secret Strategy That Hastened the Collapse of the Soviet... (ebook). Atlantic Monthly Press. pp. p 86. ISBN 0-87113-633-3. Retrieved 2006-07-10.

{{cite book}}:|pages=has extra text (help); Cite has empty unknown parameters:|origmonth=,|origdate=, and|coauthors=(help); Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ a b Peter D. Hannaford, Remembering Reagan, Regnery Publishing, 2000, ISBN 0895265141, Google Print, p.170, p.171

- ^ Stefan Auer, Liberal Nationalism in Central Europe, Routledge, 2004, ISBN 0415314798, Google Print, p.70

- ^ Gary Clyde Hufbauer, Jeffrey J. Schott, Kimberly Ann Elliott, Economic Sanctions Reconsidered: History and Current Policy, Institute for International Economics, 1990, ISBN 0881321362, Google Print, p.193

- ^ a b c Sabrina P. Ramet, Social Currents in Eastern Europe, Duke University Press, 1995, ISBN 0822315483, Google Print, p.89

- ^ Kenney, Padraic (2003). A Carnival of Revolution : Central Europe 1989. Princeton University Press. pp. p 30. ISBN 0-691-11627-X.

{{cite book}}:|pages=has extra text (help); Cite has empty unknown parameters:|origdate=and|coauthors=(help) - ^ a b "Keeping the fire burning: the underground movement (1982-83)". BBC News. Retrieved 2006-07-10.

- ^ Ramet, op.cit, Google Print, p.90

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j "Negotiations and the big debate (1984-88)". BBC News. Retrieved 2006-07-10.

- ^ AROUND THE WORLD; Poland Says Mrs. Walesa Can Accept Nobel Prize, New York Times, November 30, 1983. Last accessed on 9 October 2006.

- ^ K. Gottesman, "Prawdziwe oświadczenie Lecha Wałęsy", Rzeczpospolita (no. 188) 12.08.2000; online version retrieved on 14 October 2006

- ^ Weigel, George (2003). The Final Revolution: The Resistance Church and the Collapse of Communism (ebook). Oxford University Press US. pp. p. 149. ISBN 0-19-516664-7. Retrieved 2006-07-10.

{{cite book}}:|pages=has extra text (help); Cite has empty unknown parameters:|origmonth=,|origdate=, and|coauthors=(help); Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ Kenney, Padraic (2003). A Carnival of Revolution : Central Europe 1989. Princeton University Press. pp. p 25. ISBN 0-691-11627-X.

{{cite book}}:|pages=has extra text (help); Cite has empty unknown parameters:|origdate=and|coauthors=(help) - ^ John Barkley Rosser, Marina V. Rosser, Comparative Economics in a Transforming World Economy, MIT Press, 2004, ISBN 0262182343, Google Print, p.283

- ^ Michael D. Kennedy, Cultural Formations of Postcommunism: Emancipation, Transition, Nation, and War, University of Minnesota Press, 2002, ISBN 0816638578, Google Print, p.71

- ^ Mary Patrice Erdmans, Helena Znaniecka Lopata, Polish Americans, Transaction Publishers, 1994, ISBN 1560001003, Google Print, p.221

- ^ John E. Jackson, Jacek Klich, Krystyna Poznanska, The Political Economy of Poland's Transition: New Firms and Reform Governments, Cambridge University Press, 2005, ISBN 0521838959, Google Print, p.21

- ^ a b c d e f g "Solidarity victorious (1989)". BBC News. Retrieved 2006-07-10.

- ^ a b c d "Free elections (1989)". BBC News. Retrieved 2006-07-10.

- ^ a b c d e f David S. Mason, David S Mason, Westview Press, 1997, ISBN 0813328357, Google Print, p.53

- ^ Changes in the Polish media since 1989. Last accessed on 9 Octover 2006.

- ^ a b Ronald J. Hill, Beyond Stalinism: Communist Political Evolution, Routledge, 1992, ISBN 0714634638 Google Print, p.51

- ^ William C. Cockerham, Health and Social Change in Russia and Eastern Europe, Routledge, 1999, ISBN 0415920809, Google Print, p.157

- ^ Arend Lijphart, Institutional Design in New Democracies, Westview Press, 1996, ISBN 0813321093, Google Print, p.62

- ^ Steger, Manfred B (2004). Judging Nonviolence: The Dispute Between Realists and Idealists (ebook). Routledge (UK). pp. p 114. ISBN 0-415-93397-8. Retrieved 2006-07-06.

{{cite book}}:|pages=has extra text (help); Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help); Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ Kenney, Padraic (2003). A Carnival of Revolution : Central Europe 1989. Princeton University Press. pp. p 15. ISBN 0-691-11627-X.

{{cite book}}:|pages=has extra text (help); Cite has empty unknown parameters:|origdate=and|coauthors=(help) - ^ Padraic Kenney, Rebuilding Poland: Workers and Communists, 1945-1950, Cornell University Press, 1996, ISBN 0801432871, Google Print, p.4

- ^ Padraic Kenney, Carnival..., Google Print, p.2

- ^ a b c d Kubicek, Paul A (2000). Unbroken Ties: The State, Interest Associations, and Corporatism in Post-Soviet Ukraine (ebook). University of Michigan Press. pp. p. 188. ISBN 0-472-11030-6. Retrieved 2006-07-10.

{{cite book}}:|pages=has extra text (help); Cite has empty unknown parameters:|origmonth=,|origdate=, and|coauthors=(help); Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ "solidarnosc.org". Retrieved 2006-07-10.

External links

- Solidarity official English homepage

- Presentation The Solidarity Phenomenon

- Solidarity 25th Anniversairy Press Center

- International Conference 'From Solidarity to Freedom'

- Poland: Solidarity -- The Trade Union That Changed The World

- Advice for East German propagandists on how to deal with the Solidarity movement

- Solidarity, Freedom and Economical Crisis in Poland, 1980-81

- Arch Puddington, How American Unions Helps Solidarity Win

- The Independent Press in Poland, 1976-1990 - this site of Library of Congress contains list of Polish abbreviations and their English translations; many of which were used in this article

- Template:Pl icon Solidarity Center Fundation - Fundacja Centrum Solidarności

Further reading

- Garton Ash, Timothy (2002). The Polish Revolution: Solidarity. Yale University Press. ISBN 0-300-09568-6.

{{cite book}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|origdate=(help) - Eringer, Robert (1982). Strike for Freedom: The Story of Lech Walesa and Polish Solidarity. Dodd Mead. ISBN 0-396-08065-0.

{{cite book}}: Cite has empty unknown parameters:|origdate=and|coauthors=(help) - Kenney, Patrick (2006). The Burdens of Freedom. Zed Books Ltd. ISBN 1-84277-662-2.

{{cite book}}: Cite has empty unknown parameters:|origdate=and|coauthors=(help) - Osa, Maryjane (2003). Solidarity and Contention: Networks of Polish Opposition. University of Minnesota Press. ISBN 0-8166-3874-8.

{{cite book}}: Cite has empty unknown parameters:|origdate=and|coauthors=(help) - Ost, David (2005). The Defeat Of Solidarity: Anger and Politics in Postcommunist Europe (ebook). Cornell University Press. ISBN 0-8014-4318-0.

{{cite book}}: Cite has empty unknown parameters:|origdate=and|coauthors=(help) - Penn, Shana (2005). Solidarity's Secret : The Women Who Defeated Communism in Poland. University of Michigan Press. ISBN 0-472-11385-2.

{{cite book}}: Cite has empty unknown parameters:|origdate=and|coauthors=(help) - Perdue, William D. (1995). Paradox of Change: The Rise and Fall of Solidarity in the New Poland. Praeger/Greenwood. ISBN 0-275-95295-9.

{{cite book}}: Cite has empty unknown parameters:|origdate=and|coauthors=(help) - Pope John Paul II, Sollicitudo Rei Socialis, on Vatican website]