Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood

The Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood (later known as the Pre-Raphaelites) was a group of English painters, poets, and art critics, founded in 1848 by William Holman Hunt, John Everett Millais and Dante Gabriel Rossetti. The three founders were joined by William Michael Rossetti, James Collinson, Frederic George Stephens and Thomas Woolner to form the seven-member "brotherhood". Their principles were shared by other artists, including Ford Madox Brown, Arthur Hughes and Marie Spartali Stillman.

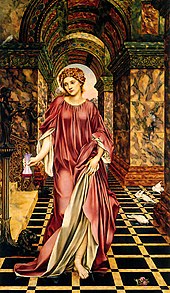

A later, medievalising strain inspired by Rossetti included Edward Burne-Jones and extended into the twentieth century with artists such as John William Waterhouse.

The group's intention was to reform art by rejecting what it considered the mechanistic approach first adopted by Mannerist artists who succeeded Raphael and Michelangelo. Its members believed the Classical poses and elegant compositions of Raphael in particular had been a corrupting influence on the academic teaching of art, hence the name "Pre-Raphaelite". In particular, the group objected to the influence of Sir Joshua Reynolds, founder of the English Royal Academy of Arts, whom they called "Sir Sloshua". To the Pre-Raphaelites, according to William Michael Rossetti, "sloshy" meant "anything lax or scamped in the process of painting ... and hence ... any thing or person of a commonplace or conventional kind".[1] The brotherhood sought a return to the abundant detail, intense colours and complex compositions of Quattrocento Italian art. The group associated their work with John Ruskin,[2] an English critic whose influences were driven by his religious background.

The group continued to accept the concepts of history painting and mimesis, imitation of nature, as central to the purpose of art. The Pre-Raphaelites defined themselves as a reform movement, created a distinct name for their form of art, and published a periodical, The Germ, to promote their ideas. The group's debates were recorded in the Pre-Raphaelite Journal.

Beginnings

The Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood was founded in John Millais's parents' house on Gower Street, London in 1848. At the first meeting, the painters John Everett Millais, Dante Gabriel Rossetti, and William Holman Hunt were present. Hunt and Millais were students at the Royal Academy of Arts and had met in another loose association, the Cyclographic Club, a sketching society. At his own request Rossetti became a pupil of Ford Madox Brown in 1848.[3] At that date, Rossetti and Hunt shared lodgings in Cleveland Street, Fitzrovia, Central London. Hunt had started painting The Eve of St. Agnes based on Keats's poem of the same name, but it was not completed until 1867.[4]

As an aspiring poet, Rossetti wished to develop the links between Romantic poetry and art. By autumn, four more members, painters James Collinson and Frederic George Stephens, Rossetti's brother, poet and critic William Michael Rossetti, and sculptor Thomas Woolner, had joined to form a seven-member-strong brotherhood.[4] Ford Madox Brown was invited to join, but the more senior artist remained independent but supported the group throughout the PRB period of Pre-Raphaelitism and contributed to The Germ. Other young painters and sculptors became close associates, including Charles Allston Collins, and Alexander Munro. The PRB intended to keep the existence of the brotherhood secret from members of the Royal Academy.[5]

Early doctrines

The brotherhood's early doctrines, as defined by William Michael Rossetti, were expressed in four declarations:

- to have genuine ideas to express;

- to study Nature attentively, so as to know how to express them;

- to sympathise with what is direct and serious and heartfelt in previous art, to the exclusion of what is conventional and self-parading and learned by rote; and

- most indispensable of all, to produce thoroughly good pictures and statues.[6]

The principles were deliberately non-dogmatic, since the brotherhood wished to emphasise the personal responsibility of individual artists to determine their own ideas and methods of depiction. Influenced by Romanticism, the members thought freedom and responsibility were inseparable. Nevertheless, they were particularly fascinated by medieval culture, believing it to possess a spiritual and creative integrity that had been lost in later eras. The emphasis on medieval culture clashed with principles of realism which stress the independent observation of nature. In its early stages, the Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood believed its two interests were consistent with one another, but in later years the movement divided and moved in two directions. The realists were led by Hunt and Millais, while the medievalists were led by Rossetti and his followers, Edward Burne-Jones and William Morris. The split was never absolute, since both factions believed that art was essentially spiritual in character, opposing their idealism to the materialist realism associated with Courbet and Impressionism.

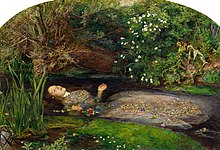

The Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood was greatly influenced by nature and its members used great detail to show the natural world using bright and sharp focus techniques on a white canvas. In attempts to revive the brilliance of colour found in Quattrocento art, Hunt and Millais developed a technique of painting in thin glazes of pigment over a wet white ground in the hope that the colours would retain jewel-like transparency and clarity. Their emphasis on brilliance of colour was a reaction to the excessive use of bitumen by earlier British artists, such as Reynolds, David Wilkie and Benjamin Robert Haydon. Bitumen produces unstable areas of muddy darkness, an effect the Pre-Raphaelites despised.

In 1848, Rossetti and Hunt made a list of "Immortals", artistic heroes whom they admired, especially from literature, some of whose work would form subjects for PRB paintings, notably including Keats and Tennyson.[7]

First exhibitions and publications

The first exhibitions of Pre-Raphaelite work occurred in 1849. Both Millais's Isabella (1848–1849) and Holman Hunt's Rienzi (1848–1849) were exhibited at the Royal Academy. Rossetti's Girlhood of Mary Virgin was shown at a Free Exhibition on Hyde Park Corner. As agreed, all members of the brotherhood signed their work with their name and the initials "PRB". Between January and April 1850, the group published a literary magazine, The Germ edited by William Rossetti which published poetry by the Rossettis, Woolner, and Collinson and essays on art and literature by associates of the brotherhood, such as Coventry Patmore. As the short run-time implies, the magazine did not manage to achieve sustained momentum. (Daly 1989)

Public controversy

In 1850, the Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood became the subject of controversy after the exhibition of Millais' painting Christ in the House of His Parents was considered to be blasphemous by many reviewers, notably Charles Dickens.[8] Dickens considered Millais' Mary to be ugly.[9] Millais had used his sister-in-law, Mary Hodgkinson, as the model for Mary in his painting. The brotherhood's medievalism was attacked as backward-looking and its extreme devotion to detail was condemned as ugly and jarring to the eye.[10] According to Dickens, Millais made the Holy Family look like alcoholics and slum-dwellers, adopting contorted and absurd "medieval" poses.[11]

After the controversy, Collinson left the brotherhood and the remaining members met to discuss whether he should be replaced by Charles Allston Collins or Walter Howell Deverell, but were unable to make a decision. From that point the group disbanded, though its influence continued. Artists who had worked in the style initially continued but no longer signed works "PRB".[12]

The brotherhood found support from the critic John Ruskin, who praised its devotion to nature and rejection of conventional methods of composition. The Pre-Raphaelites were influenced by Ruskin's theories. He wrote to The Times defending their work and subsequently met them. Initially, he favoured Millais, who travelled to Scotland in the summer of 1853 with Ruskin and Ruskin's wife, Euphemia Chalmers Ruskin, née Gray (now best known as Effie Gray). The main object of the journey was to paint Ruskin's portrait.[13] Effie became increasingly attached to Millais,[14] creating a crisis. In subsequent annulment proceedings, Ruskin himself made a statement to his lawyer to the effect that his marriage had been unconsummated. [15] The marriage was annulled on grounds of non-consummation, leaving Effie free to marry Millais,[16] but causing a public scandal. Millais began to move away from the Pre-Raphaelite style after his marriage, and Ruskin ultimately attacked his later works. Ruskin continued to support Hunt and Rossetti and provided funds to encourage the art of Rossetti's wife Elizabeth Siddall.

By 1853 the original PRB had virtually dissolved,[17] with only Holman Hunt remaining true to its stated aims. But the term "Pre-Raphaelite" stuck to Rossetti and others, including William Morris and Edward Burne-Jones, with whom he became involved in Oxford in 1857.[18] Hence the term Pre-Raphaelite is associated with the much wider and long-lived art movement, including the dreamy, yearning images of women produced by Rossetti and several of his followers.

Later developments and influence

Artists influenced by the brotherhood include John Brett, Philip Calderon, Arthur Hughes, Gustave Moreau, Evelyn De Morgan,[19] Frederic Sandys (who entered the Pre-Raphaelite circle in 1857)[19] and John William Waterhouse. Ford Madox Brown, who was associated with them from the beginning, is often seen as most closely adopting the Pre-Raphaelite principles. One follower who developed his own distinct style was Aubrey Beardsley, who was pre-eminently influenced by Burne-Jones.[19]

After 1856, Dante Gabriel Rossetti became an inspiration for the medievalising strand of the movement. He was the link between the two types of Pre-Raphaelite painting (nature and Romance) after the PRB became lost in the later decades of the century. Rossetti, although the least committed to the brotherhood, continued the name and changed its style. He began painting versions of femme fatales using models like Jane Morris, in paintings such as Proserpine, The Blue Silk Dress, and La Pia de' Tolomei. His work influenced his friend William Morris, in whose firm Morris, Marshall, Faulkner & Co. he became a partner, and with whose wife Jane he may have had an affair. Ford Madox Brown and Edward Burne-Jones also became partners in the firm. Through Morris's company, the ideals of the Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood influenced many interior designers and architects, arousing interest in medieval designs and other crafts leading to the Arts and Crafts movement headed by William Morris. Holman Hunt was involved with the movement to reform design through the Della Robbia Pottery company.

After 1850, Hunt and Millais moved away from direct imitation of medieval art. They stressed the realist and scientific aspects of the movement, though Hunt continued to emphasise the spiritual significance of art, seeking to reconcile religion and science by making accurate observations and studies of locations in Egypt and Palestine for his paintings on biblical subjects. In contrast, Millais abandoned Pre-Raphaelitism after 1860, adopting a much broader and looser style influenced by Reynolds. William Morris and others condemned his reversal of principles.

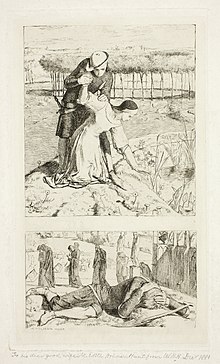

Pre-Raphaelitism had a significant impact in Scotland and on Scottish artists. The figure in Scottish art most associated with the Pre-Raphaelites was the Aberdeen-born William Dyce (1806–64). Dyce befriended the young Pre-Raphaelites in London and introduced their work to Ruskin.[20] His later work was Pre-Raphaelite in its spirituality, as can be seen in his The Man of Sorrows and David in the Wilderness (both 1860), which contain a Pre-Raphaelite attention to detail.[21] Joseph Noel Paton (1821-1901) studied at the Royal Academy schools in London, where he became a friend of Millais and he subsequently followed him into Pre-Raphaelitism, producing pictures that stressed detail and melodrama such as The Bludie Tryst (1855). His later paintings, like those of Millais, have been criticised for descending into popular sentimentality.[22] Also influenced by Millais was James Archer (1823-1904) and whose work includes Summertime, Gloucestershire (1860)[22] and who from 1861 began a series of Arthurian-based paintings including La Morte d'Arthur and Sir Lancelot and Queen Guinevere.[23]

Pre-Raphaelism also inspired painters like Lawrence Alma-Tadema.[24]

The movement influenced many later British artists into the 20th century. Rossetti came to be seen as a precursor of the wider European Symbolist movement. In the late 20th century the Brotherhood of Ruralists based its aims on Pre-Raphaelitism, while the Stuckists and the Birmingham Group have also derived inspiration from it.

Birmingham Museum & Art Gallery has a world-renowned collection of works by Burne-Jones and the Pre-Raphaelites that, some claim, strongly influenced the young J. R. R. Tolkien,[25] who wrote The Hobbit and The Lord of the Rings, with influences taken from the same mythological scenes portrayed by the Pre-Raphaelites.

In the 20th century artistic ideals changed, and art moved away from representing reality. Since the Pre-Raphaelites were fixed on portraying things with near-photographic precision, though with a distinctive attention to detailed surface-patterns, their work was devalued by many painters and critics. After the First World War, British Modernists associated Pre-Raphaelite art with the repressive and backward times in which they grew up. In the 1960s there was a major revival of Pre-Raphaelitism. Exhibitions and catalogues of works, culminating in a 1984 exhibition in London's Tate Gallery, re-established a canon of Pre-Raphaelite work.[26] Among many other exhibitions, there was another large show at Tate Britain in 2012–13.[27]

List of artists

Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood

- James Collinson (painter)

- William Holman Hunt (painter)

- John Everett Millais (painter)

- Dante Gabriel Rossetti (painter, poet)

- William Michael Rossetti (critic)

- Frederic George Stephens (critic)

- Thomas Woolner (sculptor, poet)

Associated artists and figures

- John Brett (painter)

- Ford Madox Brown (painter, designer)

- Lucy Madox Brown (painter, writer)

- Richard Burchett (painter, educator)

- Edward Burne-Jones (painter, designer)

- Charles Allston Collins (painter)

- Frank Cadogan Cowper (painter)

- Fanny Cornforth (artist's model)

- Walter Deverell (painter)

- Fanny Eaton (artist's model)

- Frederick Startridge Ellis (publisher, editor, poet)

- Effie Gray (artist's model)

- Henry Holiday (painter, stained-glass artist, illustrator)

- Arthur Hughes (painter, book illustrator)

- Edward Robert Hughes (painter and artist's model)

- Mary Lizzie Macomber (painter)

- Robert Braithwaite Martineau (painter)

- Annie Miller (artist's model)

- Jane Morris (artist's model)

- Louisa, Marchioness of Waterford (painter and artist's model)

- May Morris (embroiderer and designer)

- William Morris (designer, writer)

- Christina Rossetti (poet and artist's model)

- John Ruskin (critic)

- Anthony Frederick Augustus Sandys (painter)

- Emma Sandys (painter)

- Thomas Seddon (painter)

- Frederic Shields (painter)

- Elizabeth Siddal (painter, poet, and artist's model)

- Simeon Solomon (painter)

- Marie Spartali Stillman (painter)

- Algernon Charles Swinburne (poet)

- Henry Wallis (painter)

- William Lindsay Windus (painter)

- Antonio Corsi (artist's model)

Loosely associated artists

- Lawrence Alma-Tadema (painter)

- Sophie Gengembre Anderson (painter)

- Wyke Bayliss (painter)

- George Price Boyce (painter)

- Joanna Mary Boyce (painter)

- Sir Frederick William Burton (painter)

- Julia Margaret Cameron (photographer)

- James Campbell (painter)

- John Collier (painter)

- William Davis (painter)

- Evelyn De Morgan (painter)

- Frank Bernard Dicksee (painter)

- John William Godward (painter)

- Thomas Cooper Gotch (painter)

- Charles Edward Hallé (painter)

- John Lee (painter)

- Edmund Leighton (painter)

- Frederic, Lord Leighton (painter)

- James Lionel Michael (minor poet, mentor to Henry Kendall)

- Charles William Mitchell (painter)

- Joseph Noel Paton (painter)

- Gustav Pope (painter)

- Frederick Marriott (painter)

- Frederick Smallfield (painter)

- James Tissot (painter)

- Elihu Vedder (painter)

- John William Waterhouse (painter)

- Daniel Alexander Williamson (painter)

- James Abbott McNeill Whistler (painter)

Illustration and poetry

Many members of the ‘inner’ Pre-Raphaelite circle (Dante Gabriel Rossetti, John Everett Millais, William Holman Hunt, Ford Madox Brown, Edward Burne-Jones) and ‘outer’ circle (Frederick Sandys, Arthur Hughes, Simeon Solomon, Henry Hugh Armstead, Joseph Noel Paton, Frederic Shields, Matthew James Lawless) were working concurrently in painting, illustration, and sometimes poetry.[28] Victorian morality judged literature as superior to painting, because of its “noble grounds for noble emotion.”[29] Robert Buchanan (a writer and opponent of the Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood) felt so strongly about this artistic hierarchy that he wrote: “The truth is that literature, and more particularly poetry, is in a very bad way when one art gets hold of another, and imposes upon it its conditions and limitations."[30] This was the hostile environment in which Pre-Raphaelites were defiantly working in various media. The Pre-Raphaelites attempted to revitalize subject painting, which had been dismissed as artificial. Their belief that each picture should tell a story was an important step for the unification of painting and literature (eventually deemed the Sister Arts[31]), or at least a break in the rigid hierarchy promoted by writers like Robert Buchanan.[32]

The Pre-Raphaelite desire for more extensive affiliation between painting and literature also manifested in illustration. Illustration is a more direct unification of these media and, like subject painting, can assert a narrative of its own. For the Pre-Raphaelites, and Dante Gabriel Rossetti specifically, there was anxiety about the constraints of illustration.[32] In 1855, Rossetti wrote to William Allingham about the independence of illustration: “I have not begun even designing for them yet, but fancy I shall try the ‘Vision of Sin’ and ‘Palace of Art’ etc. – those where one can allegorize on one’s own hook, without killing for oneself and everyone a distinct idea of the poet’s."[32] This passage makes apparent Rossetti’s desire to not just support the poet’s narrative, but to create an allegorical illustration that functions separately from the text as well. In this respect, Pre-Raphaelite illustrations go beyond depicting an episode from a poem, but rather function like subject paintings within a text.

Collections

There are major collections of Pre-Raphaelite work in United Kingdom museums such as the Birmingham Museum and Art Gallery, the Tate Gallery, Victoria and Albert Museum, Manchester Art Gallery, Lady Lever Art Gallery, and Liverpool's Walker Art Gallery. The Art Gallery of South Australia and the Delaware Art Museum in the US have the most significant collections of Pre-Raphaelite art outside the UK. The Museo de Arte de Ponce in Puerto Rico also has a notable collection of Pre-Raphaelite works, including Sir Edward Burne-Jones' The Last Sleep of Arthur in Avalon, Frederic Lord Leighton's Flaming June, and works by William Holman Hunt, John Everett Millais, Dante Gabriel Rossetti, and Frederic Sandys.

There is a set of Pre-Raphaelite murals in the Old Library at the Oxford Union, depicting scenes from the Arthurian legends, painted between 1857 and 1859 by a team of Dante Gabriel Rossetti, William Morris, and Edward Burne-Jones. The National Trust houses at Wightwick Manor, Wolverhampton, and at Wallington Hall, Northumberland, both have significant and representative collections. Andrew Lloyd Webber is an avid collector of Pre-Raphaelite works, and a selection of 300 items from his collection were shown at an exhibition at the Royal Academy in London in 2003.

Kelmscott Manor, the country home of William Morris from 1871 until his death in 1896, is owned by the Society of Antiquaries of London and is open to the public. The Manor is featured in Morris' work News from Nowhere. It also appears in the background of Water Willow, a portrait of his wife, Jane Morris, painted by Dante Gabriel Rossetti in 1871. There are exhibitions connected with Morris and Rossetti’s early experiments with photography.

Portrayal in popular culture

The story of the brotherhood, from its controversial first exhibition to being embraced by the art establishment, has been depicted in two BBC television series. The first, The Love School, was broadcast in 1975; the second is the 2009 BBC television drama serial Desperate Romantics by Peter Bowker. Although much of the latter's material is derived from Franny Moyle's factual book Desperate Romantics: The Private Lives of the Pre-Raphaelites,[33] the series occasionally departs from established facts in favour of dramatic licence and is prefaced by the disclaimer: "In the mid-19th century, a group of young men challenged the art establishment of the day. The pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood were inspired by the real world around them, yet took imaginative licence in their art. This story, based on their lives and loves, follows in that inventive spirit."[34]

Ken Russell's television film Dante's Inferno (1967) contains brief scenes on some of the leading Pre-Raphaelites but mainly concentrates on the life of Rossetti, played by Oliver Reed.

See also

- List of Pre-Raphaelite paintings

- New English Art Club

- Early Renaissance painting

- English school of painting

- Hogarth Club

- John Wharlton Bunney

- Florence Claxton

- James Smetham

- The Light of the World

- Nazarenes

Notes and sources

- Notes

- ^ Hilton, Timothy (1970). The Pre-Raphaelites, p. 46. Oxford University Press.

- ^ Landow, George P. "Pre-Raphaelites: An Introduction". The Victorian Web. Retrieved 15 June 2014.

- ^ McGann, Jerome J. The Complete Writings and Pictures of Dante Gabriel Rossetti, NINES consortium, Creative Commons License; http://www.rossettiarchive.org/docs/s40.rap.html retrieved 16 December 2012.

- ^ a b Hilton (1970), pp. 28–33.

- ^ "Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood 1848 - 1855 - HiSoUR Art Culture Exhibition". HiSoUR Art Culture Exhibition. 22 February 2017. Retrieved 27 December 2017.

- ^ Quoted by Latham, pp. 11-12; see also his comments

- ^ https://www.bl.uk/romantics-and-victorians/articles/the-pre-raphaelites

- ^ Slater, Michael (2009). Charles Dickens, p. 309. Yale University Press.

- ^ Andres, Sophia (2005). The Pre-Raphaelite Art of the Victorian Novel: Narrative Challenges to Visual Gendered Boundaries, p. 9. Ohio State University Press.

- ^ The Times, Saturday, 3 May 1851; pg. 8; Issue 20792: Exhibition of the Royal Academy. (Private View.), First Notice: "We cannot censure at present, as amply or as strongly as we desire to do, that strange disorder of the mind or the eyes which continues to rage with unabated absurdity among a class of juvenile artists who style themselves "P.R.B.," which being interpreted means Pre-Raphael Brethren. Their faith seems to consist in an absolute contempt for perspective and the known laws of light and shade, an aversion to beauty in every shape, and a singular devotion to the minute accidents of their subjects, including, or rather seeking out, every excess of sharpness and deformity."

- ^ Fowle, Frances (2000). "Sir John Everett Millais, Bt, Christ in the House of His Parents ('The Carpenter's Shop'), 1849-50". Tate. Retrieved 28 January 2019.

{{cite web}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|dead-url=(help) - ^ "Pre-Raphaelites: An Introduction". www.victorianweb.org. Retrieved 28 January 2019.

- ^ Dearden, James S. (1999). John Ruskin: A Life in Pictures, pp. 36–37. Sheffield Academic Press.

- ^ Phyllis Rose, Parallel Lives: Five Victorian Marriages, 1983, pp. 49–94.

- ^ Lutyens, Mary. (1967). Millais and the Ruskins. London: John Murray. p. 191. ISBN 0719517001.

- ^ Dearden (1999), p. 43.

- ^ Clarke, Michael (2010). The concise Oxford dictionary of art terms - Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood. Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 9780199569922.

- ^ Whiteley, Jon (1989). Oxford and the Pre-Raphaelites. Oxford: Ashmolean Museum. ISBN 0907849946.

- ^ a b c Hilton (1970), pp. 202–05

- ^ D. Macmillan, Scottish Art 1460-1990 (Edinburgh: Mainstream, 1990), ISBN 0500203334, p. 348.

- ^ M. MacDonald, Scottish Art (London: Thames and Hudson, 2000), ISBN 0500203334, p. 100.

- ^ a b D. Macmillan, Scottish Art 1460-1990 (Edinburgh: Mainstream, 1990), ISBN 0500203334, p. 213.

- ^ R. Barber, The Holy Grail: Imagination and Belief (Harvard University Press, 2004), ISBN 0674013905, p. 275.

- ^ "Fine Art Books Art Instruction | Photography Books | Visual Arts Periods, Groups & Movements: Pre-Raphaelites". fineartbookstore.com. Retrieved 27 December 2017.

- ^ See, for example, Bucher (2004) for a brief discussion on the influence of the Pre-Raphaelites on Tolkien.

- ^ Barringer, Tim (1999). Reading the Pre-Raphaelites, p. 17. Yale University Press.

- ^ Pre-Raphaelites: Victorian Avant-Garde, Tate Britain, accessed 27 August 2014

- ^ Goldman, Paul (2004). Victorian Illustration: The Pre-Raphaelites, the Idyllic School and the High Victorians. Burlington, VT: Lund Humphries. pp. 1–51.

- ^ Welland, Dennis S. R. (1953). The Pre-Raphaelites in Literature and Art. London, UK: George G. Harrap & Co. Ltd. p. 14.

- ^ Buchanan, Robert W. (October 1871). "The Fleshly School of Poetry: Mr. D.G. Rossetti". The Contemporary Review. as cited in Welland, D.S.R. The Pre-Raphaelites in Literature and Art. London, UK: George G. Harrap & Co. Ltd., 14.

- ^ "Chapter One: Ruskin's Theories of the Sister Arts — Ut Pictura Poesis". www.victorianweb.org. Retrieved 21 November 2017.

- ^ a b c Rossetti, Dante Gabriel (1855). Letter from D.G. Rossetti to William Allingham.

{{cite book}}:|work=ignored (help) - ^ Desperate Romantics press pack: introduction BBC Press Office. Retrieved on 24 July 2009.

- ^ Armstrong, Stephen (5 July 2009). "BBC2 drama on icons among Pre-Raphaelites". The Sunday Times. Retrieved 25 July 2009.

- Sources

- Barringer, Tim (1998). Reading the Pre-Raphaelites. New Haven, Conn.: Yale University Press. ISBN 0-300-07787-4.

- Bucher, Gregory (2004). "Review of Matthew Dickerson. 'Following Gandalf. Epic Battles and Moral Victory in The Lord of the Rings'", Journal of Religion & Society, 6, ISSN 1522-5658, webpage accessed 13 October 2007

- Daly, Gay (1989). Pre-Raphaelites in Love. New York: Ticknor & Fields. ISBN 0-89919-450-8.

- Dickerson, Matthew (2003). Following Gandalf : epic battles and moral victory in the Lord of the rings, Grand Rapids, Mich. : Brazos Press, ISBN 1-58743-085-1

- Gaunt, William (1975). The Pre-Raphaelite Tragedy (rev. ed.). London: Cape. ISBN 0-224-01106-5.

- Hawksley, Lucinda (1999). Essential Pre-Raphaelites. Bath: Dempsey Parr. ISBN 1-84084-524-4.

- Latham, David, Haunted Texts: Studies in Pre-Raphaelitism in Honour of William E. Fredeman, William Evan Fredeman, David Latham, eds, 2003, University of Toronto Press, ISBN 0802036627, 9780802036629, google books

- Prettejohn, Elizabeth (2000). The Art of the Pre-Raphaelites. Princeton, N.J.: Princeton University Press. ISBN 0-691-07057-1.

- Ramm, John (2003). "The Forgotten Pre-Raphaelite: Henry Wallis", Antique Dealer & Collectors Guide, 56 (March/April), p. 8–9

Further reading

- Andres, Sophia. (2005) The Pre-Raphaelite Art of the Victorian Novel: Narrative Challenges to Visual Gendered Boundaries. Ohio State University Press, ISBN 0-8142-5129-3

- Bate, P.H. [1901] (1972) The English Pre-Raphaelite painters : their associates and successors, New York : AMS Press, ISBN 0-404-00691-4

- Daly, G. (1989) Pre-Raphaelites in Love, New York : Ticknor & Fields, ISBN 0-89919-450-8

- des Cars, L. (2000) The Pre-Raphaelites : Romance and Realism, Abrams Discoveries series, New York : Harry N. Abrams, ISBN 0-8109-2891-4

- Mancoff, D.N. (2003) Flora symbolica : flowers in Pre-Raphaelite art, Munich ; London ; New York : Prestel, ISBN 3-7913-2851-4

- Marsh, J. and Nunn, P.G. (1998) Pre-Raphaelite women artists, London : Thames & Hudson, ISBN 0-500-28104-1

- Sharp, Frank C and Marsh, Jan, (2012) The Collected Letters of Jane Morris, Boydell & Brewer, London

- Staley, A. and Newall, C. (2004) Pre-Raphaelite vision : truth to nature, London : Tate, ISBN 1-85437-499-0

- Townsend, J., Ridge, J. and Hackney, S. (2004) Pre-Raphaelite painting techniques : 1848–56, London : Tate, ISBN 1-85437-498-2

External links

- Birmingham Museums & Art Gallery's Pre-Raphaelite Online Resource

- Pre-Raphaelites exhibition at Tate Britain

- Liverpool Walker Art Gallery's Pre-Raphaelite collection

- Pre-Raphaelitism Lecture by John Ruskin

- The Pre-Raphaelite Society

- Pre-Raphaelite online resource project at the Birmingham Museums & Art Gallery

- The Samuel and Mary R. Bancroft Collection of Pre-Raphaelite Art

- Edward Burne-Jones, Victorian artist-dreamer, full text exhibition catalog from The Metropolitan Museum of Art

- Pre-Raphaelite murals in the Old Library at the Oxford Union]. This podcast covers their painting. Oxford Brookes University has a series of podcasts on the Pre-Raphaelites in Oxford, with this one on YouTube dedicated to the Union murals.