Willow (1988 film)

| Willow | |

|---|---|

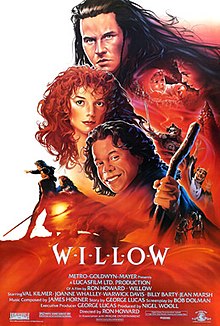

Theatrical release poster by John Alvin | |

| Directed by | Ron Howar |

| Screenplay by | Bob Dolman |

| Story by | George Lucas |

| Produced by | Joe Johnston Nigel Wooll |

| Starring | |

| Cinematography | Adrian Biddle |

| Edited by | Daniel P. Hanley Mike Hill Richard Hiscott |

| Music by | James Horner |

Production companies | |

| Distributed by | Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer[N 1] |

Release date |

|

Running time | 126 minutes[2] |

| Country | United States[1] |

| Language | English |

| Budget | $35 million[3] |

| Box office | $57.3 million |

Willow is a 1988 American high fantasy film directed by Ron Howard, produced and with a story by George Lucas, and starring Warwick Davis, Val Kilmer, Joanne Whalley, Jean Marsh, and Billy Barty. Davis plays the eponymous lead character and hero: a reluctant farmer who plays a critical role in protecting a special baby from a tyrannical queen who vows to destroy her and take over the world in a high fantasy setting.

Lucas conceived the idea for the film in 1972, approaching Howard to direct during the post-production phase of Cocoon in 1985. Bob Dolman was brought in to write the screenplay, coming up with seven drafts before finishing in late 1986. It was then set up at Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer and principal photography began in April 1987, finishing the following October. The majority of filming took place at Elstree Studios in Hertfordshire, England, as well as Wales and New Zealand. Industrial Light & Magic created the visual effects sequences, which led to a revolutionary breakthrough with digital morphing technology. The film was released in 1988 to mixed reviews from critics, but was a modest financial success, received two Academy Award nominations, and has developed a cult following amongst fantasy fans.

Plot

When a prophecy states that a female child with a special birthmark will herald the downfall of the evil sorceress Queen Bavmorda, she imprisons all pregnant women in her realm to prevent its fulfillment. When the child is born, the mother begs the midwife to smuggle the infant to safety. The midwife reluctantly accepts and leaves Nockmaar Castle unnoticed. The mother is executed; the midwife is hunted down and eventually found. Knowing she cannot escape, the midwife sets the baby on a makeshift raft of grass and sends her down a river before being killed by Nockmaar hounds. Bavmorda, furious about the escape, sends her daughter Sorsha and her army's commander, General Kael, to find the baby.

The baby drifts downriver to a village of Nelwyn (dwarves). She comes into the care of Willow Ufgood, a kind farmer and conjurer with hopes to become a real sorcerer. His wife Kaiya and his children fall in love with the baby immediately, and Willow, after some resistance, quickly grows to love her as well. The next day the village is attacked by a lone Nockmaar hound; after the village warriors kill it, they deduce it was after a baby. Willow reveals the baby to the High Aldwin, the village sorcerer, who declares the child is special and that she must be taken back to the Daikini (humans). Willow, due to his love for the child, is selected to accompany the party of volunteers in returning the baby. At the Daikini Crossroads, they find a human warrior named Madmartigan trapped in a crow's cage. While the rest of the party wants to give the baby to Madmartigan and go home immediately, Willow and his friend Meegosh refuse, so the others leave. After spending the night at the crossroads and meeting an army led by Airk Thaughbaer, an old friend of Madmartigan's marching against Bavmorda, Willow reluctantly decides to free Madmartigan and hand the baby over to him.

As Meegosh and Willow are headed home, they find the baby was stolen by a group of Brownies. They chase the Brownies and are trapped, but are rescued by the Fairy Queen Cherlindrea. Cherlindrea tells Willow that the baby is Elora Danan, the future empress of Tir Asleen, and Bavmorda's bane. She gives Willow her wand and assigns him the task of helping Elora fulfill her destiny. Willow sends Meegosh home, and two of the Brownies, Franjean and Rool, are assigned to help Willow find the sorceress Fin Raziel. The three of them find Madmartigan at a tavern, where he is disguised as a woman to hide from Llug, a cuckolded husband. Sorsha arrives and reveals his identity; Llug, furious upon the realization that Madmartigan is not a woman, starts a brawl, allowing Willow, Madmartigan, and the brownies to escape. Madmartigan guides them to the lake where Raziel lives before departing.

The companions find Raziel, but discover she has been transformed into a possum by Bavmorda. Willow and his party return with her to shore but encounter Sorsha, who already has Madmartigan in custody. They are taken to a snowbound mountain camp of the Nockmaar army where Willow tries to restore Raziel, but turns her into a rook instead. Madmartigan is accidentally dosed with love dust by the Brownies during their escape and ends up declaring his undying love for Sorsha, much to her disbelief. The prisoners escape with the baby and reach a village at the foot of the mountain. While hiding, they again encounter Airk and what remains of his army, recently defeated by Bavmorda's forces. Madmartigan proclaims his loyalty to the Nelwyn and promises to protect Willow and Elora.

Willow and Madmartigan take Sorsha hostage, but she escapes to tell Kael where they are going. They arrive at the castle of Tir Asleen only to discover that it is now overrun by trolls and the inhabitants have all been cursed by Bavmorda. Madmartigan gathers armor and weapons to prepare for the assault from Kael and Sorsha. During the fighting, Sorsha realizes she has developed feelings for Madmartigan and joins him and Willow in opposing her mother. Willow accidentally turns a troll into an eborsisk, a massive, fire-breathing, two-headed dragon-like monster that begins attacking everything it sees until Madmartigan kills it. Airk arrives with his army, turning the tide of battle. Kael kidnaps Elora and escapes to Nockmaar where he reports Sorsha's betrayal to Bavmorda. She orders the preparation of the ritual to banish Elora's soul.

Airk's army, Willow, and the others arrive at Nockmaar to lay siege, but Bavmorda turns most of them into pigs. Willow escapes when Raziel has him use a protective spell. He succeeds in turning Raziel human again, and she removes Bavmorda's spell from the army. They trick their way into the castle and, in the ensuing battle, Airk is killed by Kael, who is in turn slain by Madmartigan. Sorsha leads Willow and Raziel to the ritual chamber, interrupting Elora's sacrifice. Bavmorda incapacitates Sorsha and then duels magically with Raziel, rendering her unconscious. Willow uses an "old disappearing pig trick" to fool Bavmorda into thinking that Elora has been sent beyond her reach; enraged, Bavmorda accidentally triggers the ritual's final stage, which results in banishing her own soul.

After the victory celebration, Willow is rewarded with a magic book to aid him in becoming a sorcerer, and Sorsha and Madmartigan remain in a restored Tir Asleen to raise Elora together. Willow returns home to a hero's welcome and is happily reunited with his family.

Cast

- Warwick Davis as Willow Ufgood, a Nelwyn dwarf and aspiring sorcerer who plays a critical role in protecting infant Elora Danan from the evil queen Bavmorda.

- Val Kilmer as Madmartigan, a boastful immured mercenary swordsman who helps Willow on his quest.

- Kate and Ruth Greenfield/Rebecca Bearman as Elora Danan, an infant princess that prophecy says will bring about Queen Bavmorda's downfall.

- Joanne Whalley as Sorsha, Bavmorda's warrior daughter who turns against her mother when she falls in love with Madmartigan.

- Jean Marsh as Queen Bavmorda, the villainous ruler of Nockmaar, a powerful black sorceress and mother of Sorsha.

- Patricia Hayes as Fin Raziel, the aging sorceress who is turned into a possum[4][5] due to a curse from Bavmorda.

- Billy Barty as The High Aldwin, the Nelwyn wizard who commissions Willow to go on his journey, realizing the potential that Willow possesses in magic.

- Pat Roach as General Kael, the villainous associate to Queen Bavmorda and high commander of her army.

- Gavan O'Herlihy as Airk Thaughbaer, the military commander of the destroyed kingdom of Galladoorn who shares a mixed friendship with Madmartigan.

- Maria Holvöe as Cherlindrea, the fairy queen who resides in the forest and updates Willow on the importance of his quest.

- Kevin Pollak and Rick Overton as Rool and Franjean, a brownie duo who also serve as comic relief in Willow's journey.

- David J. Steinberg as Meegosh, Willow's closest friend who accompanies Willow partway on his journey.

- Mark Northover as Burglekutt, the leader of the Nelwyn village council who maintains a running enmity with Willow.

- Phil Fondacaro as Vohnkar, a Nelwyn warrior who also accompanies Willow partway on his journey.

- Julie Peters as Kaiya Ufgood, Willow's wife; a loving mother and enthusiastic in caring for Elora.

- Malcolm Dixon as a Nelwyn warrior.

- Tony Cox as a Nelwyn warrior.

Production

Development

George Lucas conceived the idea for the film (originally titled Munchkins) in 1972. Similar in intent to Star Wars, he created "a number of well-known mythological situations for a young audience".[6][7] During the production of Return of the Jedi in 1982, Lucas approached Warwick Davis, who was portraying Wicket the Ewok, about playing Willow Ufgood. Five years passed before he was actually cast in the role. Lucas "thought it would be great to use a little person in a lead role. A lot of my movies are about a little guy against the system, and this was just a more literal interpretation of that idea."[6]

Lucas explained that he had to wait until the mid-1980s to make the film because visual effects technology was finally advanced enough to execute his vision.[7] Meanwhile, actor-turned-director Ron Howard was looking to do a fantasy film. He was at Industrial Light & Magic during the post-production phase of Cocoon, when he was first approached by Lucas to direct Willow. He had previously starred in Lucas's American Graffiti,[8] and Lucas felt that he and Howard shared a symbiotic relationship similar to the one he enjoyed with Steven Spielberg. Howard nominated Bob Dolman to write the screenplay based on Lucas's story. Dolman had worked with him on a 1983 television pilot called Little Shots that had not resulted in a series, and Lucas admired Dolman's work on the sitcom WKRP in Cincinnati.[9]

Dolman joined Howard and Lucas at Skywalker Ranch for a series of lengthy story conferences, and wrote seven drafts of his script between the spring and fall of 1986.[9] Pre-production began in late 1986. Various major film studios turned down the chance to distribute and co-finance it with Lucasfilm because they believed the fantasy genre was unsuccessful. This was largely due to films such as Krull, Legend, Dragonslayer, and Labyrinth.[10] Lucas took it to Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer (MGM), which was headed by Alan Ladd Jr. Ladd and Lucas shared a relationship as far back as the mid-1970s, when Ladd, running 20th Century Fox, greenlighted Lucas's idea for Star Wars.[11] However, in 1986, MGM was facing financial troubles, and major investment in a fantasy film was perceived as a risk. Ladd advanced half the $35 million budget for it in return for theatrical and television rights, leaving Lucasfilm with home video and pay television rights to offer in exchange for the other half.[11] RCA/Columbia Pictures Home Video paid $15 million to Lucas in exchange for the video rights.[12]

Lucas based the character of General Kael (Pat Roach) on the film critic Pauline Kael,[13] a fact that was not lost on Kael in her printed review of the film. She referred to General Kael as an "homage a moi". Similarly, the two-headed dragon was called an "Eborsisk" after film critics Gene Siskel and Roger Ebert.[3]

Filming

Principal photography began on April 2, 1987, and ended the following October. Interior footage took place at Elstree Studios in Hertfordshire, England, while location shooting took place in Wales and New Zealand.[11] Lucas initially visualized shooting the film similar to Return of the Jedi, with studio scenes at Elstree and locations in Northern California, but the idea eventually faded. However, some exteriors were done around Skywalker Ranch and on location at Burney Falls, near Mount Shasta.[14] The Chinese government refused Lucas the chance for a brief location shoot. He then sent a group of photographers to South China to photograph specific scenery, which was then used for background blue screen footage. Tongariro National Park in New Zealand was chosen to house Bavmorda's castle.[14]

Visual effects

Lucasfilm's Industrial Light & Magic (ILM) created the visual effects sequences. The script called for Willow to restore Fin Raziel (Patricia Hayes) from a goat to her human form. Willow recites what he thinks is the appropriate spell, but turns the goat into an ostrich, a peacock, a tortoise and, finally, a tiger, before returning her to normal. ILM supervisor Dennis Muren considered using stop motion animation for the scene.[15] He also explained that another traditional and practical way in the late 1980s to execute this sequence would have been through the use of an optical dissolve with cutaways at various stages.[11]

Muren found both stop motion and optical effects to be too technically challenging and decided that the transformation scene would be a perfect opportunity for ILM to create advances with digital morphing technology. He proposed filming each animal, and the actress doubling for Hayes, and then feeding the images into a computer program developed by Doug Smythe.[11] The program would then create a smooth transition from one stage to another before outputting the result back onto film. Smythe began development of the necessary software in September 1987. By March 1988, the impressive result Muren and fellow designer David Allen achieved what would represent a breakthrough for computer-generated imagery (CGI).[11] The techniques developed for the sequence were later utilized by ILM for Indiana Jones and the Last Crusade, Terminator 2: Judgment Day, and Star Trek VI: The Undiscovered Country.[16]

The head of ILM's animation department, Wes Takahashi, supervised the film's animation sequences.[17]

Soundtrack

| Willow | |

|---|---|

| Soundtrack album by | |

| Released | 1988 |

| Genre | Film music |

| Length | 69:23 |

| Label | Virgin |

| Producer | James Horner, Shawn Murphy |

The film score was written by James Horner and performed by the London Symphony Orchestra.[18]

"I am a musicologist, a doctor of music. Therefore I listened to, studied and analysed a lot of music. I also enjoy metaphors, the art of quoting and of cycles. The harmonic draft of the Willow score, and most particularly its spiritual side, came from such a cycle, from such mythology and music history that I was taught, and that I myself convey with my own emotions and compositions."[19]

Eclectic influences on the score include Leoš Janáček's Glagolitic Mass, Mozart's "Requiem", "The Nine Splendid Stags" from Béla Bartók, Edvard Grieg's "Arabian Dance" for the theater play Peer Gynt, and compositions by Sergei Prokofiev.[19]

"Willow's Theme" purposefully (see Horner's quote above) contains a reworking/alteration of part of the theme of the first movement ("Lebhaft") of Robert Schumann's Symphony No. 3 referencing it, while "Elora Danan's Theme" shows a reference to the Bulgarian folk song "Mir Stanke Le" (Мир Станке ле), also known as the "Harvest Song from Thrace".

- Track listing[18]

- "Elora Danan" – 9:45

- "Escape from the Tavern" – 5:04

- "Willow's Journey Begins" – 5:26

- "Canyon of Mazes" – 7:52

- "Tir Asleen" – 10:47

- "Willow's Theme" – 3:54

- "Bavmorda's Spell is Cast" – 18:11

- "Willow the Sorcerer" – 11:55

Reception

Box office

The film was shown and promoted at the 1988 Cannes Film Festival.[20][21] It was released on May 20, 1988, in 1,209 theaters, earning $8,300,169 in its opening weekend, placing number one at the weekend box office. Lucas had hoped it would earn as much money as E.T. the Extra-Terrestrial,[21] but the film faced early competition with Crocodile Dundee II, Big and Rambo III.[22] Making over $57 million at the North American box office,[23] it was not the blockbuster hit insiders had anticipated.[24] It was not, however, a financial flop either, as it made a profit because of strong international, home video, and television sales.[25]

Critical response

The film was released to mixed reviews from critics.[21] As of March 2019, based on 51 reviews collected by Rotten Tomatoes, 51% of the critics gave the film a positive review with an average score of 5.8/10.[26]

Janet Maslin from The New York Times praised Lucas's storytelling, but was critical of Ron Howard's direction. "Howard appears to have had his hands full in simply harnessing the special effects," Maslin said.[27]

Desson Thomson writing in The Washington Post, explained "Rob Reiner's similar fairytale adventure The Princess Bride (which the cinematographer Adrian Biddle also shot) managed to evoke volumes more without razzle-dazzle. It's a sad thing to be faulting Lucas, maker of the Star Wars trilogy and Raiders of the Lost Ark, for forgetting the tricks of entertainment."[28] Mike Clark in USA Today wrote that "the rainstorm wrap-up, in which Good edges Evil is like Led Zeppelin Meets The Wild Bunch. The film is probably too much for young children and possibly too much of the same for cynics. But any 6–13-year-old who sees this may be bitten by the ’movie bug’ for life."[11]

Accolades

At the Academy Awards, the film was nominated for Sound Effects Editing and Visual Effects, but lost both to Who Framed Roger Rabbit, which was similarly done by Industrial Light & Magic.[29] It won Best Costume Design at the Saturn Awards, where it was also nominated for Warwick Davis for Best Performance by a Younger Actor (lost to Fred Savage for Vice Versa) and Jean Marsh for Best Supporting Actress (lost to Sylvia Sidney for Beetlejuice). It also lost Best Fantasy Film[30] and the Hugo Award for Best Dramatic Presentation to Who Framed Roger Rabbit.[31] It was also nominated for two Golden Raspberry Awards including Worst Screenplay, which lost to Cocktail and Worst Supporting Actor for Billy Barty, who lost to Dan Aykroyd for Caddyshack II.[32]

Home media

The film was first released on VHS, Betamax, Video 8, and LaserDisc on November 22, 1988 by RCA Columbia Pictures Home Video and had multiple re-releases on VHS in the 1990s under Columbia-TriStar Home Video as well as a Widescreen LaserDisc in 1995. 20th Century Fox Home Entertainment re-released the film on VHS and on DVD for the first time as a "special edition" in November 2001. The release included an audio commentary by Warwick Davis and two "making of" featurettes. In the commentary, Davis confirms that there were a number of "lost scenes" previously rumored to have been deleted from it including a battle in the valley, Willow battling a boy who transforms into a shark in a lake while retrieving Fin Raziel, and an extended sorceress duel at the climax.[33] 20th Century Fox Home Entertainment released the film on Blu-ray Disc on March 12, 2013, with an all-new transfer supervised by George Lucas.[34] Following Disney's acquisition of Lucasfilm, the film was re-released by Walt Disney Studios Home Entertainment on Blu-ray, DVD, and Digital (for the first time) on January 29, 2019.

Other media

Board game

In 1988, Tor Books released The Willow Game,[35] a two- to six-player adventure board game based on the film and designed by Greg Costikyan.

Video games

Three video games based on the film were released. Mindscape published an action game in 1988 for Amiga, Atari ST, Commodore 64, and DOS.[36] Japanese game developer Capcom published two different games in 1989 based on the film; the first Willow is a platform game for the arcades and the second Willow game is a role-playing game for the Nintendo Entertainment System.[37][38]

Novels

Wayland Drew adapted Lucas's story into a film novel,[39] providing additional background information to several major characters and various additional scenes, including an encounter with a lake monster near Razel's island which was filmed, but ultimately not used in the movie. A segment of that scene's filmed material can be found in the DVD's "Making of Willow" documentary.

Lucas outlined the Chronicles of the Shadow War trilogy to follow the film and hired comic book writer/novelist Chris Claremont to adapt them into a series of books. They take place about fifteen years after the original film and feature the teenage Elora Danan as a central character.

- Shadow Moon (1995) ISBN 0-553-57285-7

- Shadow Dawn (1996) ISBN 0-553-57289-X

- Shadow Star (2000) ISBN 0-553-57288-1

Sequel

Beginning in 2005, Lucas and Davis discussed the possibility of a television series serving as a sequel to Willow.[40] Throughout the years, in various interviews, Davis expressed interest in reprising his role as the titular character.[41][42][43]

By May 2018, Howard confirmed that there were ongoing discussions regarding a sequel, while confirming the project would not be called Willow 2.[44] In March of 2019, Ron Howard announced that a sequel television series is currently in development, with intentions for the series to be exclusively released on the Disney+ streaming service. Jake Kasdan will write the television series, while Warwick Davis will reprise his role from the original film.[45][46][47]

Notes

- ^ The film's distribution rights were transferred from Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer to Walt Disney Studios

References

- ^ "Willow (1988)". American Film Institute. Retrieved November 10, 2017.

- ^ "WILLOW (PG)". British Board of Film Classification. November 17, 1988. Archived from the original on November 5, 2014. Retrieved November 4, 2014.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|dead-url=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ a b Gray, Beverly. Ron Howard: from Mayberry to the moon-and beyond, page 134. Rutledge Hill Press, Nashville, Tennessee (2003). ISBN 1-55853-970-0.

- ^ Shannon, Jody Duncan (August 1988). "Willow". Cinefex, p. 178

- ^ Vinge, Joan D.; Lucas, George (1988). Willow: The Novel Based on the Motion Picture. London: Piper. ISBN 0-330-30631-6

- ^ a b Hearn, Marcus (2005). The Cinema of George Lucas. New York City: Harry N. Abrams, Inc. p. 153. ISBN 0-8109-4968-7.

- ^ a b Harmetz, Aljean (May 21, 1987). "'Star Wars' Is 10, And Lucas Reflects". The New York Times. Retrieved October 19, 2015.

- ^ Howard, Ron (2005). "Forward". The Cinema of George Lucas. New York City: Harry N. Abrams, Inc. ISBN 0-8109-4968-7.

- ^ a b Hearn, p.154-155

- ^ Harmetz, Aljean (June 9, 1988). "A Pained Lucas Ponders Attacks on 'Willow'". The New York Times. Archived from the original on March 7, 2016. Retrieved October 19, 2015.

{{cite news}}: Unknown parameter|dead-url=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ a b c d e f g Hearn, p.156-157

- ^ Wasko, Janet (June 26, 2013). Hollywood in the Information Age: Beyond the Silver Screen. John Wiley & Sons. ISBN 9780745678337.

- ^ Van Gelder, Lawrence (September 4, 2001). "Pauline Kael, Provocative and Widely Imitated New Yorker Film Critic, Dies at 82". The New York Times. Retrieved July 13, 2008.

- ^ a b Baxter, John (October 1999). Mythmaker: The Life and Work of George Lucas. New York City: Avon. pp. 365–366. ISBN 0-380-97833-4.

- ^ Baxter, p.367

- ^ Failes, Ian (April 3, 2018). "Over 30 Years, WILLOW has Morphed into an Effects Classic". VFX Voice. Retrieved April 4, 2018.

- ^ "Subject: Wes Ford Takahashi". Animators' Hall of Fame. Archived from the original on August 12, 2016. Retrieved June 14, 2016.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|dead-url=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ a b Hobart, Tavia. "Willow [Original Score]". AllMusic. Retrieved January 20, 2009.

- ^ a b Martin, Jean-Baptiste (June 3, 2013). "Willow: Between Quotes". jameshorner-filmmusic.com. Archived from the original on January 5, 2014. Retrieved January 4, 2014.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|dead-url=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ "Festival de Cannes: Willow". festival-cannes.com. Archived from the original on August 7, 2012. Retrieved July 31, 2009.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|dead-url=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ a b c Baxter, p.372

- ^ "'Crocodile Dundee II' Top Film at Box Office". The New York Times. Associated Press. June 9, 1988. Archived from the original on March 7, 2016. Retrieved October 19, 2015.

{{cite news}}: Unknown parameter|dead-url=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ "Willow". Box Office Mojo. Archived from the original on February 7, 2009. Retrieved December 23, 2008.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|dead-url=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ Wasko, Janet. Hollywood in the information age: beyond the silver screen, page 198. Polity Press/Blackwell Publishers, UK (1994). ISBN 0-292-79093-7.

- ^ Maltby, Richard. Hollywood cinema: second edition, page 198. Blackwell Publishing, UK (1994). ISBN 0-631-21614-6.

- ^ "Willow". Rotten Tomatoes. Retrieved December 23, 2008.

- ^ Maslin, Janet (May 20, 1988). "'Willow,' a George Lucas Production". The New York Times. Archived from the original on January 27, 2016. Retrieved October 19, 2015.

{{cite news}}: Unknown parameter|dead-url=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ Desson, Howe (May 20, 1988). "Willow". The Washington Post. Retrieved October 19, 2015.

- ^ "Willow". Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences. Retrieved December 23, 2008.[permanent dead link]

- ^ "Past Saturn Awards". Academy of Science Fiction, Fantasy & Horror Films. Archived from the original on December 19, 2008. Retrieved December 23, 2008.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ "1989 Hugo Awards". Internet Movie Database. Archived from the original on June 6, 2009. Retrieved December 23, 2008.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|dead-url=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ "Ninth Annual RAZZIE Awards (for 1988)". Golden Raspberry Award Foundation. Archived from the original on May 30, 2009. Retrieved December 23, 2008.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|dead-url=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ "Willow (Special Edition) (1988)". Amazon.com. Archived from the original on December 20, 2008. Retrieved December 23, 2008.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|dead-url=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ Webb, Charles. "Forget 'The Hobbit' - 'Willow' Is Coming To DVD And Blu-ray". Archived from the original on January 18, 2013. Retrieved January 30, 2013.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|dead-url=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ "The Willow Game (1988)". BoardGameGeek. Archived from the original on July 7, 2015. Retrieved November 25, 2014.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|dead-url=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ "Willow for Amiga, Atari ST, Commodore 64, DOS". MobyGames. Archived from the original on December 20, 2016. Retrieved February 15, 2017.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|dead-url=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ "The Unconverted: Arcade Games that never made it Home". Retro Gamer. No. 123. Imagine Publishing. December 2013. p. 82.

- ^ "Sala de Maquinas". Superjuegos. No. 82. February 1999. p. 118.

- ^ Drew, Wayland, Bob Dolman, and George Lucas. Willow: A Novel. New York: Ballantine Books, 1988. ISBN 0345351959.

- ^ Vespe, Eric "Quint" (April 24, 2005). "CELEBRATION is had by many a STAR WARS geek! Lucas talks! Footage shown! Details here!". Ain't It Cool News. Archived from the original on May 31, 2009. Retrieved December 23, 2008.

{{cite news}}: Unknown parameter|dead-url=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ https://www.news.com.au/finance/business/media/warwick-davis-on-star-wars-episode-viii-cliffhanger-possible-willow-sequel/news-story/3bdaf75c7ecf8f2d90e23eaa49157c97

- ^ Adler, Shawn (June 13, 2008). "Warwick Davis Enthusiastic About Possibility For 'Willow 2'". MTV News. Retrieved December 23, 2008.

- ^ Larnick, Eric (March 12, 2013). "Warwick Davis, 'Willow' Star, on the 25th Anniversary, Sequel Plans, and George Lucas (EXCLUSIVE)". moviefone.com. Archived from the original on June 10, 2013.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|dead-url=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ https://comicbook.com/starwars/2018/05/13/willow-sequel-ron-howard-lucasfilm/

- ^ Josh Horowitz [@joshuahorowitz] (April 30, 2019). "DISNEY+ is developing a WILLOW series based on a pitch by @JonKasdan. It's a continuation and would feature @WarwickADavis. Straight from @RealRonHoward's mouth to a greenlight please!!! You in, @valkilmer?" (Tweet) – via Twitter.

- ^ Butler, Mary Anne (May 1, 2019). "Ron Howard Confirms 'Willow' TV Series Talks for Disney+, with Warwick Davis". Bleeding Cool. Retrieved May 1, 2019.

- ^ Thorne, Will (May 1, 2019). "Ron Howard in Talks for 'Willow' Sequel Series at Disney+". Variety. Retrieved May 2, 2019.

{{cite web}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|dead-url=(help)

Further reading

- Drew, Wayland (January 1988). Willow: A Novel. Del Rey Books. ISBN 978-0-345-35195-1. (Novelization of the film)

- Duffy, Jo (January 1988). Willow. St. Martin's Press. ISBN 978-0-87135-367-2. (Comic book adaptation of the film)

- Varney, Allen W.; Goldberg, Eric (September 1988). The Willow Sourcebook. St. Martin's Press. ISBN 978-0-312-93083-7.

External links

- Willow at Lucasfilm.com

- Willow at IMDb

- Willow at the TCM Movie Database

- Willow at Box Office Mojo

- Willow at Rotten Tomatoes

- 1988 films

- Willow (film)

- 1980s fantasy films

- American films

- American fantasy adventure films

- English-language films

- Films directed by Ron Howard

- Films shot in Hertfordshire

- Fantasy adventure films

- American fantasy-comedy films

- High fantasy films

- Films about fairies and sprites

- Films about shapeshifting

- 1988 soundtracks

- Films scored by James Horner

- Film soundtracks

- James Horner albums

- Virgin Records soundtracks

- Films shot at Elstree Studios

- Lucasfilm films

- Imagine Entertainment films

- Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer films

- Films set in the Middle Ages

- Films adapted into comics

- Dwarves in popular culture

- Films about witchcraft

- Films about wizards