2020 Atlantic hurricane season

| 2020 Atlantic hurricane season | |

|---|---|

Season summary map | |

| Seasonal boundaries | |

| First system formed | May 16, 2020 |

| Last system dissipated | Season ongoing |

| Strongest storm | |

| Name | Laura |

| • Maximum winds | 150 mph (240 km/h) (1-minute sustained) |

| • Lowest pressure | 937 mbar (hPa; 27.67 inHg) |

| Seasonal statistics | |

| Total depressions | 26 |

| Total storms | 25 |

| Hurricanes | 9 |

| Major hurricanes (Cat. 3+) | 3 |

| Total fatalities | 146 total |

| Total damage | ≥ $26.373 billion (2020 USD) |

| Related articles | |

The 2020 Atlantic hurricane season is an ongoing tropical cyclone season which has featured tropical cyclone formation at a record-breaking rate. So far, there have been a total of 26 tropical or subtropical cyclones, 25 named storms, 9 hurricanes, and 3 major hurricanes.[nb 1] With 25 named storms, it is the second most active Atlantic hurricane season on record, behind only the 2005 Atlantic hurricane season. It is also only the second tropical cyclone season to feature the Greek letter storm naming system, with the other season again being 2005. The season officially started on June 1 and will officially end on November 30; however, formation of tropical cyclones is possible at any time, as illustrated by the formations of tropical storms Arthur and Bertha, on May 16 and 27, respectively. This marked the record sixth consecutive year with pre-season systems.

During the season, Tropical Storm Cristobal and 21 later systems have broken the record for the earliest formation by storm number. Of the 25 named storms, 10 made landfall in the contiguous United States, breaking the record of nine set in 1916. In addition, the season is the first to see seven named tropical cyclones make landfall in the continental United States before September.[2][3] This activity has been fueled by an ongoing La Niña, which developed during the summer months of 2020.

In early June, Cristobal caused 15 deaths and $665 million in damage across Mexico, Guatemala, and the United States.[nb 2] In July, Tropical Storm Fay brought gusty winds across Delaware, New Jersey, and Coastal New York, resulting in $350 million in damage and six deaths. Tropical Storm Gonzalo brought minor impacts to southern parts of the Lesser Antilles. Hanna, the season's first hurricane, made landfall in South Texas as a Category 1 hurricane, leaving at least $875 million in damage. Isaias, the second hurricane of the season, brought impacts to much of the Eastern Caribbean and Florida, made landfall in North Carolina as a Category 1 hurricane, and brought widespread power outages and a destructive tornado outbreak to the Eastern United States, causing an overall $5.225 billion in damage.

In August, hurricanes Marco and Laura threatened the U.S. Gulf Coast. Although Marco ultimately weakened and caused minimal impacts at landfall, Laura became the strongest tropical cyclone on record in terms of wind speed to make landfall in Louisiana, alongside the 1856 Last Island hurricane.[4] Overall, Laura caused at least $14.1 billion in damage and 77 deaths. September was the most active month on record in the Atlantic, with ten named storms. Hurricane Nana impacted Central America, destroying many acres of banana crop, and Tropical Storm Rene struck the Cabo Verde Islands as a weak tropical storm. Later, Hurricane Paulette made landfall in Bermuda, while Hurricane Sally severely impacted the Southeastern United States. A massive Hurricane Teddy made its way to Atlantic Canada, making landfall as an extratropical cyclone after a long journey in the Atlantic, while also becoming the fourth largest tropical cyclone by gale-force winds on record. By mid-September, the active Atlantic spawned a brief subtropical storm, Alpha, that made an unprecedented landfall in Portugal after becoming the easternmost-forming (sub)tropical cyclone in the North Atlantic basin on record. Tropical Storm Beta formed in the Gulf of Mexico, affecting Texas and Louisiana. With 10 (sub)tropical storms, September 2020 was the most active month on record. In early October, Tropical Storm Gamma struck Mexico's Yucatán Peninsula. Hurricane Delta then impacted a large swath of the Western Caribbean while also becoming the season's third major hurricane. Delta made landfall in the Yucatán and then in Louisiana, becoming the 10th named storm to strike the continental U.S. this season.

Early on, officials in the United States expressed concerns the hurricane season could potentially exacerbate the effects of the COVID-19 pandemic for U.S. coastal residents.[5][6] As expressed in an op-ed of the Journal of the American Medical Association, "there exists an inherent incompatibility between strategies for population protection from hurricane hazards: evacuation and sheltering (ie, transporting and gathering people together in groups)," and "effective approaches to slow the spread of COVID-19: physical distancing and stay-at-home orders (ie, separating and keeping people apart)."[7]

Seasonal forecasts

| Source | Date | Named storms |

Hurricanes | Major hurricanes |

Ref |

| Average (1981–2010) | 12.1 | 6.4 | 2.7 | [8] | |

| Record high activity | 28 | 15 | 7 | [9] | |

| Record low activity | 4 | 2† | 0† | [9] | |

| ––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––– | |||||

| TSR | December 19, 2019 | 15 | 7 | 4 | [10] |

| CSU | April 2, 2020 | 16 | 8 | 4 | [11] |

| TSR | April 7, 2020 | 16 | 8 | 3 | [12] |

| UA | April 13, 2020 | 19 | 10 | 5 | [13] |

| TWC | April 15, 2020 | 18 | 9 | 4 | [14] |

| NCSU | April 17, 2020 | 18–22 | 8–11 | 3–5 | [15] |

| PSU | April 21, 2020 | 15–24 | n/a | n/a | [16] |

| SMN | May 20, 2020 | 15–19 | 7–9 | 3–4 | [17] |

| UKMO* | May 20, 2020 | 13* | 7* | 3* | [18] |

| NOAA | May 21, 2020 | 13–19 | 6–10 | 3–6 | [19] |

| TSR | May 28, 2020 | 17 | 8 | 3 | [20] |

| CSU | June 4, 2020 | 19 | 9 | 4 | [21] |

| UA | June 12, 2020 | 17 | 11 | 4 | [22] |

| CSU | July 7, 2020 | 20 | 9 | 4 | [23] |

| TSR | July 7, 2020 | 18 | 8 | 4 | [24] |

| TWC | July 16, 2020 | 20 | 8 | 4 | [25] |

| CSU | August 5, 2020 | 24 | 12 | 5 | [26] |

| TSR | August 5, 2020 | 24 | 10 | 4 | [27] |

| NOAA | August 6, 2020 | 19–25 | 7–11 | 3–6 | [28] |

| ––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––– | |||||

| Actual activity |

25 | 9 | 3 | ||

| * June–November only † Most recent of several such occurrences. (See all) | |||||

Forecasts of hurricane activity are issued before each hurricane season by noted hurricane experts, such as Philip J. Klotzbach and his associates at Colorado State University, and separately by NOAA forecasters.

Klotzbach's team (formerly led by William M. Gray) defined the average (1981 to 2010) hurricane season as featuring 12.1 tropical storms, 6.4 hurricanes, 2.7 major hurricanes (storms reaching at least Category 3 strength in the Saffir–Simpson hurricane scale), and an accumulated cyclone energy (ACE) index of 106 units.[11] NOAA defines a season as above normal, near normal or below normal by a combination of the number of named storms, the number reaching hurricane strength, the number reaching major hurricane strength, and the ACE Index.[29]

Pre-season forecasts

On December 19, 2019, Tropical Storm Risk (TSR), a public consortium consisting of experts on insurance, risk management, and seasonal climate forecasting at University College London, issued an extended-range forecast predicting a slightly above-average hurricane season. In its report, the organization called for 15 named storms, 7 hurricanes, 4 major hurricanes, and an ACE index of 105 units. This forecast was based on the prediction of near-average trade winds and slightly warmer than normal sea surface temperatures (SSTs) across the tropical Atlantic as well as a neutral El Niño–Southern Oscillation (ENSO) phase in the equatorial Pacific.[10] On April 2, 2020, forecasters at Colorado State University echoed predictions of an above-average season, forecasting 16 named storms, 8 hurricanes, 4 major hurricanes, and an ACE index of 150 units. The organization posted significantly heightened probabilities for hurricanes tracking through the Caribbean and hurricanes striking the U.S. coastline.[11] TSR updated their forecast on April 7, predicting 16 named storms, 8 hurricanes, 3 major hurricanes, and an ACE index of 130 units.[12] On April 13, the University of Arizona (UA) predicted a potentially hyperactive hurricane season: 19 named storms, 10 hurricanes, 5 major hurricanes, and accumulated cyclone energy index of 163 units.[13] A similar prediction of 18 named storms, 9 hurricanes, and 4 major hurricanes was released by The Weather Company on April 15.[14] Following that, North Carolina State University released a similar forecast on April 17, also calling for a possibly hyperactive season with 18–22 named storms, 8–11 hurricanes and 3–5 major hurricanes.[15] On April 21 the Pennsylvania State University Earth Science System Center also predicted high numbers, 19.8 +/- total named storms, range 15-24, best estimate 20.[16]

On May 20, Mexico's Servicio Meteorológico Nacional released their forecast for an above-average season with 15–19 named storms, 7–9 hurricanes and 3–4 major hurricanes.[17] The UK Met Office released their outlook that same day, predicting average activity with 13 tropical storms, 7 hurricanes, and 3 major hurricanes expected to develop between June and November 2020. They also predicted an ACE index of around 110 units.[18] NOAA issued their forecast on May 21, calling for a 60% chance of an above-normal season with 13–19 named storms, 6–10 hurricanes, 3–6 major hurricanes, and an ACE index between 110% and 190% of the median. They cited the ongoing warm phase of the Atlantic multidecadal oscillation and the expectation of continued ENSO-neutral or even La Niña conditions during the peak of the season as factors that would increase activity.[19]

Mid-season forecasts

On June 4, Colorado State University released an updated forecast, calling for 19 named storms, 9 hurricanes, and 4 major hurricanes.[21] On July 7, Colorado State University released another updated forecast, calling for 20 named storms, 9 hurricanes, and 4 major hurricanes.[23] On July 7, Tropical Storm Risk released an updated forecast, calling for 18 named storms, 8 hurricanes, and 4 major hurricanes.[24] On July 16, The Weather Company released an updated forecast, calling for 20 named storms, 8 hurricanes, and 4 major hurricanes.[25]

On August 5, Colorado State University released an additional updated forecast, their final for 2020, calling for a near-record-breaking season, predicting a total of 24 named storms, 12 hurricanes, and 5 major hurricanes, citing the anomalously low wind shear and surface pressures across the basin during the month of July and substantially warmer than average tropical Atlantic and developing La Niña conditions.[30] On August 5, Tropical Storm Risk released an updated forecast, their final for 2020, also calling for a near-record-breaking season, predicting a total of 24 named storms, 10 hurricanes, and 4 major hurricanes, citing the favorable July trade winds, low wind shear, warmer than average tropical Atlantic, and the anticipated La Niña.[31] The following day, NOAA released their second forecast for the season whilst calling for an "extremely active" season containing 19–25 named storms, 7–11 hurricanes, and 3–6 major hurricanes. This was one of the most active forecasts ever released by NOAA for an Atlantic hurricane season.[32]

Seasonal summary

| Tropical / subtropical storm formation records set during the 2020 Atlantic hurricane season | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Storm number |

Earliest | Next earliest | ||

| Name | Date formed | Name | Date formed | |

| 3 | Cristobal | June 2, 2020 | Colin | June 5, 2016 |

| 5 | Edouard | July 6, 2020 | Emily | July 11, 2005 |

| 6 | Fay | July 9, 2020 | Franklin | July 21, 2005 |

| 7 | Gonzalo | July 22, 2020 | Gert | July 24, 2005 |

| 8 | Hanna | July 24, 2020 | Harvey | August 3, 2005 |

| 9 | Isaias | July 30, 2020 | Irene | August 7, 2005 |

| 10 | Josephine | August 13, 2020 | Jose | August 22, 2005 |

| 11 | Kyle | August 14, 2020 | Katrina | August 24, 2005 |

| 12 | Laura | August 21, 2020 | Luis | August 29, 1995 |

| 13 | Marco | August 22, 2020 | Maria | September 2, 2005 |

| Lee | September 2, 2011 | |||

| 14 | Nana | September 1, 2020 | Nate | September 5, 2005 |

| 15 | Omar | September 1, 2020 | Ophelia | September 7, 2005 |

| 16 | Paulette | September 7, 2020 | Philippe | September 17, 2005 |

| 17 | Rene | September 7, 2020 | Rita | September 18, 2005 |

| 18 | Sally | September 12, 2020 | Stan | October 2, 2005 |

| 19 | Teddy | September 14, 2020 | "Azores" | October 4, 2005 |

| 20 | Vicky | September 14, 2020 | Tammy | October 5, 2005 |

| 21 | Wilfred | September 18, 2020 | Vince | October 8, 2005 |

| 22 | Alpha | September 18, 2020 | Wilma | October 17, 2005 |

| 23 | Beta | September 18, 2020 | Alpha | October 22, 2005 |

| 24 | Gamma | October 3, 2020 | Beta | October 27, 2005 |

| 25 | Delta | October 5, 2020 | Gamma | November 15, 2005 |

Tropical cyclogenesis began in the month of May, with tropical storms Arthur and Bertha. This marked the first occurrence of two pre-season tropical storms in the Atlantic since 2016, the first occurrence of two named storms in the month of May since 2012, and the record sixth consecutive season with pre-season activity, extending the record set from 2015 to 2019. Tropical Storm Cristobal formed on June 1, coinciding with the official start of the Atlantic hurricane season, also making Cristobal the earliest-named third storm on record in the Atlantic basin. Tropical Storm Dolly also formed in June. Tropical storms Edouard, Fay, and Gonzalo, along with hurricanes Hanna and Isaias, formed in July. The season saw the development of seven consecutive tropical storms that failed to reach hurricane status, the first occurrence of such a phenomenon since 2013. Hanna became the first hurricane of the season and struck South Texas, while Isaias became the second hurricane of the season and caused widespread damage in portions of the Caribbean and United States. Tropical Depression Ten also formed in late July off the coast of West Africa, although it did not reach tropical storm status and quickly dissipated. Nonetheless, July 2020 tied 2005 for the most active July on record in the basin in terms of named systems.[33][34]

August saw the formations of tropical storms Josephine and Kyle, and hurricanes Laura and Marco. Marco ultimately became the third hurricane of the season, but rapidly weakened before making landfall in southeast Louisiana. Laura subsequently became the fourth hurricane, and first major hurricane of the season, before making landfall in southwest Louisiana at Category 4 strength with 150 mph (240 km/h) winds. The month concluded with the formation of Tropical Depression Fifteen, which intensified into Tropical Storm Omar on September 1.

September featured the formations of tropical storms Rene, Vicky, Wilfred, and Beta, Subtropical Storm Alpha, and hurricanes Nana, Paulette, Sally, and Teddy. This swarm of storms coincided with the peak of the hurricane season and the development of La Niña conditions.[35][36] Hurricane Sally made landfall near Miami, Florida as a tropical depression before causing extensive damage throughout the Southeastern United States, as a category 2 hurricane. Teddy, the season's eighth and second major hurricane, initially formed on September 12, while Tropical Storm Vicky formed two days later. With the formation of Vicky, five tropical cyclones were simultaneously active in the Atlantic basin for the first time since 1995. On September 16, three Category 2 hurricanes were simultaneously active: Paulette, Sally, and Teddy. Paulette became the first storm to strike Bermuda since Hurricane Gonzalo in 2014, while Sally struck Gulf Shores, Alabama on the same day and location where Hurricane Ivan made landfall in 2004, causing severe damage. Meanwhile, Hurricane Teddy went on to strike Atlantic Canada as an extremely large extratropical cyclone on September 23. Additionally, Paulette briefly reformed as a tropical storm before once again becoming post-tropical. Within a six hour span on September 18, Wilfred, Alpha, and Beta became named systems, an event only previously recorded in 1893.[37] Alpha impacted the Iberian Peninsula, and was the first named storm to make landfall in Portugal. Beta's intensification into a tropical storm made September 2020 the most active month on record with 10 cyclones becoming named. Beta went on to impact Texas, Louisiana, and Mississippi before transitioning into a remnant low over Alabama, marking an abrupt end to the 18 straight days of activity.[38]

After a period of inactivity, Tropical Depression Twenty-Five developed in the western Caribbean Sea on October 2 before further strengthening into Tropical Storm Gamma early the next day and impacting the Yucatan Peninsula the day after that. Early on October 5, Tropical Storm Delta developed in the Caribbean Sea south of Jamaica before becoming the ninth hurricane of the season early the next day. It then impacted a large swath of the Western Caribbean while also becoming the season's third major hurricane. Delta is now threatening the U.S. Gulf Coast.

The 2020 season has featured activity at a record pace. The season's third named storm and all named storms from the fifth onwards have formed on an earlier date in the year than any other season since reliable records began in 1851. The accumulated cyclone energy (ACE) index for the 2020 Atlantic hurricane season, as of 15:00 UTC October 10, is 119.55 units.[nb 3] Broadly speaking, ACE is a measure of the power of a tropical or subtropical storm multiplied by the length of time it existed. It is only calculated for full advisories on specific tropical and subtropical systems reaching or exceeding wind speeds of 39 mph (63 km/h).

Systems

Tropical Storm Arthur

| Tropical storm (SSHWS) | |

| Duration | May 16 – May 19 |

|---|---|

| Peak intensity | 60 mph (95 km/h) (1-min); 990 mbar (hPa) |

On May 14, The NHC began monitoring an area of disturbed weather which was expected to form just north of Cuba in a couple of days. The interaction of an upper-level trough and a stalled front over the Florida Straits led to the formation of a low-pressure area in that region on May 15. The system moved north-northeast and developed into a tropical depression east of Florida around 18:00 UTC on May 16, before an Air Force reconnaissance aircraft found that it had become Tropical Storm Arthur six hours later. Arthur weaved along the Gulf Stream and changed little in intensity as it encountered increasing wind shear. After passing east of North Carolina, the system reached peak winds of 60 mph (95 km/h) as deep convection partially covered the center. Shortly after, Arthur interacted with another front and became an extratropical cyclone by 12:00 UTC on May 20. The low turned southeast before dissipating near Bermuda a day later.[39]

Featuring the formation of a pre-season tropical storm, the 2020 Atlantic hurricane season became the record sixth consecutive season with a tropical or subtropical cyclone before the official June 1 start date.[40] Passing within 20 nautical miles of the Outer Banks, Arthur caused tropical storm force wind gusts and a single report of sustained tropical storm force winds at Alligator River Bridge.[41] Arthur caused $112,000 in damage in Florida.[42] No damage was reported in North Carolina, although gusty winds in the Bahamas damaged temporary tents and shelters which had been set up for Hurricane Dorian relief efforts.[39]

Tropical Storm Bertha

| Tropical storm (SSHWS) | |

| Duration | May 27 – May 28 |

|---|---|

| Peak intensity | 50 mph (85 km/h) (1-min); 1005 mbar (hPa) |

On May 24, a trough of low pressure developed over the southeastern Gulf of Mexico. Widespread convection accompanied the system, though its overall structure remained disorganized as it moved northeast across the Gulf. An increase in convection in the system over Florida developed a distinct low pressure area, but the system remained disorganized as it paralleled the East Coast throughout May 26. However, on May 27 a small, well-defined low with centralized convection developed off the coast of South Carolina and the system was classified as a tropical storm. Based on Doppler radar and buoy data, the system attained peak winds of 50 mph (85 km/h) shortly before moving inland near Isle of Palms. Turning north and accelerating, the system quickly degraded and transitioned into an extratropical cyclone over Virginia. On May 29 Bertha was absorbed by a larger extratropical low over Quebec. [43]

The precursor disturbance to Bertha caused a significant multi-day rainfall event across South Florida, with accumulations of 8–10 in (200–250 mm) across several locations, and with a maximum 72-hour accumulation of 14.19 in (360 mm) in Miami.[44] Damage was primarily limited to localized flooding, especially around canals, and an EF1 tornado caused minor damage in southern Miami.[45][46] Some flash flooding and tree damage occurred near the landfall location in South Carolina, though overall effects from the storm were negligible.[43][47] One person drowned due to rip currents along the coast of Myrtle Beach.[48] Overall, Bertha caused at least $133,000 in damage.[49][50]

Tropical Storm Cristobal

| Tropical storm (SSHWS) | |

| Duration | June 1 – June 10 |

|---|---|

| Peak intensity | 60 mph (95 km/h) (1-min); 992 mbar (hPa) |

On May 31, the NHC began to note that Tropical Depression Two-E in the Eastern Pacific, later to be Tropical Storm Amanda, would have the potential to redevelop in the Bay of Campeche.[51] Amanda would then make landfall in Guatemala, its low-level circulation dissipating by 21:00 UTC that day. Its remnants moved north-northwest to the Bay of Campeche and began to re-develop over the Yucatán Peninsula.[52] At 21:00 UTC on June 1, the remnants of Amanda redeveloped into Tropical Depression Three over the Bay of Campeche. The depression very slowly moved west over the Bay of Campeche, being designated Cristobal after intensifying into a tropical storm at 15:15 UTC June 2. This marked the earliest third named storm in the Atlantic, beating the previous record set by Tropical Storm Colin which became a tropical storm on June 5, 2016.[53] Throughout the remainder of the day, Cristobal's windfield became more symmetrical and well defined[54] and it gradually strengthened with falling barometric pressure as the storm meandered towards the Mexican coastline.[55] Cristobal made landfall as a strong tropical storm just west of Ciudad del Carmen at 13:35 UTC on June 3 at its peak intensity of 60 mph (97 km/h). As Cristobal moved very slowly inland, it weakened back down to tropical depression status as the overall structure of the storm deteriorated while it remained quasi-stationary over southeastern Mexico.

The storm began accelerating northwards on June 5[56] and by 18:00 UTC that day, despite being situated inland over the Yucatán peninsula, Cristobal had reintensified back to tropical storm status. As Cristobal moved further north into the Gulf of Mexico, dry air and interaction with an upper-level trough to the east began to strip Cristobal of any central convection, with most of the convection being displaced east and north of the center.[57][58] Just after 22:00 UTC on June 7, Cristobal made landfall over southeastern Louisiana. Cristobal weakened to a tropical depression the next day as it moved inland over the state. Cristobal, however, survived as a depression as it moved up the Mississippi River Valley, until finally becoming extratropical at 03:00 UTC on June 10 over southern Wisconsin. On June 10, Cristobal Entered Canada. On June 12 Cristobal Turned Into A Remnant Low And Fully Disspated On June 13.[59][60]

On June 1, the government of Mexico issued a tropical storm warning from Campeche westward to Puerto de Veracruz. Residents at risk were evacuated. Nine thousand Mexican National Guard members were summoned to aid in preparations and repairs.[61] Significant rain fell across much of Southern Mexico and Central America. Wave heights up to 9.8 ft (3 m) high closed ports for several days. In El Salvador, a mudslide caused 7 people to go missing. Up to 9.6 in (243 mm) of rain fell in the Yucatán Peninsula, flooding sections of a highway. Street flooding occurred as far away as Nicaragua.[61] On June 5, while Cristobal was still a tropical depression, a tropical storm watch was issued from Punta Herrero to Rio Lagartos by the government of Mexico as well as for another area from Intracoastal City, Louisiana to the Florida-Alabama border, issued by the National Weather Service. These areas were later upgraded to warnings and for the Gulf Coast, the warning was extended to the Okaloosa/Walton County line.[59] Heavy rains and damage were reported within the warning areas during Cristobal's passage and the storm caused an estimated US$665 million in damage.

Tropical Storm Dolly

| Tropical storm (SSHWS) | |

| Duration | June 22 – June 24 |

|---|---|

| Peak intensity | 45 mph (75 km/h) (1-min); 1002 mbar (hPa) |

On June 19, the NHC began monitoring an area of disturbed weather off the southeastern U.S. coast for possible subtropical development in the short term.[62] At the time, the low pressure system was not considered likely to develop due to unfavorable sea surface temperatures.[63] Contrary to predictions, the low moved south into the Gulf Stream in the afternoon of June 22, and new thunderstorm activity began to fire near the circulation.[64] The low's convective activity rapidly became more defined and well organized while the circulation became closed, prompting the National Hurricane Center to upgrade the system into Subtropical Depression Four at around 21:00 UTC on June 22. On June 23, the system's wind field had contracted significantly, becoming more characteristic of a tropical cyclone, while also strengthening further with winds to gale force, allowing the NHC to upgrade the system and designate it as Tropical Storm Dolly at approximately 16:15 UTC with winds of 45 mph (72 km/h). However, Dolly's peak intensity proved to be short-lived as its central convection began to diminish while it drifted over colder ocean waters. At 15:00 UTC on June 24, Dolly became a post-tropical cyclone, with any remaining convection displaced well to the system's south and the remaining circulation exposed.[65]

Dolly's formation marked the third-earliest occurrence of the fourth named storm in the calendar year on record, behind only Tropical Storm Debby of 2012[nb 4] and Tropical Storm Danielle of 2016.[9][66]

Tropical Storm Edouard

| Tropical storm (SSHWS) | |

| Duration | July 4 – July 7 |

|---|---|

| Peak intensity | 45 mph (75 km/h) (1-min); 1007 mbar (hPa) |

On July 1, a cluster of thunderstorms known as a mesoscale convective vortex formed over the northern Tennessee Valley and slowly moved southeastwards.[67] By July 2, the remnant low emerged off the coast of Georgia,[68] and the NHC began monitoring the low around 00:00 UTC on July 4.[69] Just four hours later, the circulation of the low subsequently became better defined and closed,[70] and at 15:00 UTC on July 4 the NHC issued its first advisory on the system as Tropical Depression Five. The system gradually drifted north-northeast towards Bermuda while little change in intensity occurred as the storm passed just 70 miles (110 km) north of the island around 09:00 UTC on July 5.[71][72] Shortly after, the storm began to accelerate northeast while failing to strengthen, having been forecast to become a tropical storm for at least 24 hours but failing to reach the intensity,[73] until a large burst of convection as a result of baroclinic forces allowed the system to tighten its circulation further and strengthen. As a result, the National Hurricane Center upgraded the system to Tropical Storm Edouard at 03:00 UTC on July 6. This made Edouard the earliest fifth named storm on record in the North Atlantic Ocean, surpassing Hurricane Emily, which became a tropical storm on July 11, 2005.[74] Edouard intensified further to a peak intensity of 1007 mb (29.74 inHg) and with maximum sustained winds of 45 mph (75 km/h) at 18:00 UTC that same day as a frontal boundary approached the storm from the northwest, effectively triggering extratropical transition that was completed three hours later while located about 450 miles southeast of Cape Race, Newfoundland.[74] The extratropical remnants of the storm would continue to travel eastward for several days over Northern Europe before finally dissipating over the Baltic Sea.

The Bermuda Weather Service issued a gale warning for the entirety of the island chain in advance of the system on July 4.[75] Unsettled weather with thunderstorms later ensued, and the depression caused tropical storm-force wind gusts and moderate rainfall on the island early on July 5, but impacts were relatively minor.[75][76]

Tropical Storm Fay

| Tropical storm (SSHWS) | |

| Duration | July 9 – July 11 |

|---|---|

| Peak intensity | 60 mph (95 km/h) (1-min); 998 mbar (hPa) |

At 00:00 UTC July 5, shortly after the formation of Tropical Storm Edouard, the NHC began to track an area of disorganized cloudiness and showers in relation to a nearly stationary surface trough in the Gulf of Mexico.[77] After meandering over the Gulf, the disturbance moved northeast towards the coast of the Florida Panhandle, and would subsequently move inland by 12:00 UTC July 6.[78] Two days later, the system re-emerged over the coast of Georgia.[79] Once offshore, the system began to organize as deep convection blossomed over the warm waters of the Gulf Stream.[80] Three hours later, the center reformed near the edge of the primary convective mass, prompting the NHC to initiate advisories on Tropical Storm Fay at 21:00 UTC, located just 40 miles east-northeast of Cape Hatteras.[81][82] Fay intensified as it moved nearly due north, reaching its peak intensity of 60 mph winds and minimum barometric pressure of 999 mbar.[83] Fay then made landfall east-northeast of Atlantic City, New Jersey at 21:00 UTC July 10.[84] It quickly lost intensity inland, and by 06:00 UTC July 11, had weakened to a tropical depression while situated about 50 mi (80 km) north of New York City.[85] The depression transitioned into a post-tropical cyclone three hours later while located roughly 30 mi (45 km) south of Albany, New York.[86]

Immediately upon formation, tropical storm warnings were issued for the coasts of New Jersey, New York, and Connecticut, as the system moved north at 7 mph.[81] Six people were directly killed due to rip currents and storm surge associated with Fay. Overall, damage from the storm on the US Eastern Coast was at least US$350 million, based on wind and storm surge damage on residential, commercial, and industrial properties.[87] Fay's July 9 formation was the earliest for a sixth named storm in the Atlantic, surpassing the record set by Tropical Storm Franklin, which formed on July 21, 2005.[88]

Tropical Storm Gonzalo

| Tropical storm (SSHWS) | |

| Duration | July 21 – July 25 |

|---|---|

| Peak intensity | 65 mph (100 km/h) (1-min); 997 mbar (hPa) |

Early on July 20, the NHC began monitoring a tropical wave over the central tropical Atlantic for possible tropical cyclone development.[89] Though in an area of only somewhat conducive conditions,[90] the wave rapidly became better organized as it moved quickly westward. By 21:00 UTC July 21, satellite imagery and scatterometer data indicated that the small low pressure system had acquired a well-defined circulation as well as sufficiently organized convection to be designated Tropical Depression Seven.[91] At 12:50 UTC on July 22, the NHC upgraded the depression to Tropical Storm Gonzalo. Gonzalo continued to intensify throughout the day, with an eyewall under a central dense overcast and hints of a developing eye becoming evident. Gonzalo would then reach its peak intensity with wind speeds of 65 mph and a minimum central pressure of 997 mbar at 09:00 UTC the next day. However, strengthening was halted as its central dense overcast was significantly disrupted when the storm entrained very dry air into its circulation from the Saharan Air Layer to its north. Convection soon redeveloped over Gonzalo's center as the system attempted to mix out the dry air from its circulation, but the tropical storm did not strengthen further due to the hostile conditions. After making landfall on the island of Trinidad as a weak tropical storm, Gonzalo weakened to a tropical depression at 18:00 UTC on July 25. Three hours later, Gonzalo opened up into a tropical wave as it made landfall in northern Venezuela.[92]

Gonzalo was the earliest recorded seventh named storm in the Atlantic basin. The previous record holder was Tropical Storm Gert, which formed on July 24, 2005.[93] On July 23, hurricane watches were issued for Barbados, St Vincent and the Grenadines, and a tropical storm watch was issued later that day for Grenada and Trinidad and Tobago.[94] After Gonzalo failed to strengthen into a hurricane on July 24, the hurricane and tropical storm watches were replaced with tropical storm warnings.[95] Tropical Storm Gonzalo brought squally weather to Trinidad and Tobago and parts of southern Grenada and northern Venezuela on July 25.[96] However, the storm's impact ended up being significantly smaller than originally anticipated.[97] The Tobago Emergency Management Agency only received two reports of damage on the island: a fallen tree on a health facility in Les Coteaux and a damaged bus stop roof in Argyle.[98]

Hurricane Hanna

| Category 1 hurricane (SSHWS) | |

| Duration | July 23 – July 27 |

|---|---|

| Peak intensity | 90 mph (150 km/h) (1-min); 973 mbar (hPa) |

At 06:00 UTC July 19, the NHC noted a tropical wave over eastern Hispaniola and the nearby waters for possible development.[99] The disturbance moved generally west-northwestwards towards Cuba and the Straits of Florida, passing through the latter by 12:00 UTC July 21.[100] In the Gulf of Mexico, where conditions were more favorable for development,[101][102] the system began to steadily organize as a broad low pressure area formed within it.[103] Surface observations along with data from an Air Force Hurricane Hunter Aircraft showed that the area of low pressure developed a closed circulation along with a well-defined center, prompting the NHC to issue advisories on Tropical Depression Eight at 03:00 UTC July 23.[104] The depression continued to become better organized throughout the day, and 24 hours after forming, it strengthened into a tropical storm, receiving the name Hanna.[105] With the system's intensification to a tropical storm on July 24, it broke the record for the earliest eighth named storm, being named 10 days earlier than the previous record of August 3, set by Tropical Storm Harvey in 2005.[106]

The system tracked westwards and steadily strengthened.[107] Over the ensuing 24 hours, Hanna underwent rapid intensification as its inner core and convection became better organized.[108] By 12:00 UTC July 25, radar and data from another Hurricane Hunter Aircraft showed that Hanna had intensified into the first hurricane of the season.[109] Hanna continued to strengthen further, reaching its peak intensity with 90 mph (140 km/h) winds by 21:00 UTC on July 25, before making landfall an hour later at Padre Island, Texas. After making a second landfall in Kenedy County, Texas at the same intensity at 23:15 UTC, the system then began to rapidly weaken, dropping to tropical depression status at 22:15 UTC the next day after crossing into Northeastern Mexico.[110][111]

Immediately after the system was classified as a tropical depression, tropical storm watches were issued for much of the Texas shoreline.[112] At 21:00 UTC on July 24, a hurricane warning was issued from Baffin Bay to Mesquite Bay, Texas, due to Hanna being forecast to become a hurricane before landfall.[113] As the hurricane approached landfall, local officials underscored the reality of the coronavirus when warning residents living in flood-prone neighborhoods about the prospect of evacuation. Additionally, Texas governor Greg Abbott announced the deployment of 17 COVID-19 mobile testing teams focused on shelters and 100 medical personnel provided by the Texas National Guard.[114] Hanna brought storm surge flooding, destructive winds, torrential rainfall, flash flooding and isolated tornadoes across South Texas and Northeastern Mexico; three fatalities were reported in Reynosa, Tamaulipas.[115]

Hurricane Isaias

| Category 1 hurricane (SSHWS) | |

| Duration | July 30 – August 5 |

|---|---|

| Peak intensity | 85 mph (140 km/h) (1-min); 987 mbar (hPa) |

The National Hurricane Center first began tracking a vigorous tropical wave off the coast of Africa on July 23.[116] The wave gradually organized and became better defined, developing a broad area of low pressure.[117] Although the system lacked a well-defined center, its threat of tropical-storm-force winds to land areas prompted its designation as Potential Tropical Cyclone Nine at 15:00 UTC on July 28.[118] The system moved just south of Dominica, and at 03:00 UTC on July 30, it organized into a tropical cyclone. Due to its precursor disturbance already having gale-force winds, it was immediately declared a tropical storm and given the name "Isaias".[119] On the following day, Isaias passed south of Puerto Rico and made landfall on the Dominican Republic. At 03:40 UTC on July 31, Isaias strengthened into a hurricane as it pulled away from the Greater Antilles.[120] The storm fluctuated in intensity afterwards, due to strong wind shear and dry air, with its winds peaking at 85 mph (137 km/h) and its central pressure falling to 987 millibars (29.1 inHg). At 15:00 UTC on August 1, Isaias made landfall on North Andros, Bahamas with winds around 80 mph (130 km/h), and the system weakened to a tropical storm at 21:00 UTC.[121][122] It then turned north-northwest, paralleling the east coast of Florida and Georgia while fluctuating between 65–70 mph (105–113 km/h) wind speeds. As the storm accelerated northeastward and approached the Carolina coastline, wind shear relaxed, allowing the storm to quickly intensify back into a Category 1 hurricane at 00:00 UTC on August 4,[123][124] and at 03:10 UTC, Isaias made landfall on Ocean Isle Beach, North Carolina, with 1-minute sustained winds of 85 mph (137 km/h).[125] Following landfall, Isaias accelerated and only weakened slowly, dropping below hurricane status at 07:00 UTC over North Carolina.[126] The storm passed over the Mid-Atlantic states and New England before transitioning into an extratropical cyclone near the American-Canadian border, and subsequently weakening progressing into Quebec.[127]

When Isaias formed as a tropical storm, it became the earliest ninth named storm on record, breaking the record of Hurricane Irene of 2005 by eight days. With its landfall on August 4, it became the earliest fifth named storm to make landfall in the United States. The previous record for the earliest fifth storm to make a U.S. landfall was August 18, set during the 1916 season.[128] Numerous tropical storm watches and warnings as well as hurricane watches and hurricane warnings were issued for the Lesser Antilles, Greater Antilles, Bahamas, Cuba, and the entire East Coast of the United States. Isaias caused devastating flooding and wind damage in Puerto Rico and the Dominican Republic. Several towns were left without electricity and drinking water in Puerto Rico, which prompted a disaster declaration by President Donald Trump. In the Dominican Republic, two people were killed by wind damage. A woman was killed in Puerto Rico after being swept away in flood waters. In the United States, Isaias triggered a large tornado outbreak that prompted the issuance of 109 tornado warnings across 12 states, including one for Hampton Roads and another for Dover, Delaware. A total of 39 tornadoes touched down with two people being killed by an EF3 tornado that struck a mobile home park in Windsor, North Carolina on August 4. This was the strongest tropical cyclone spawned tornado since Hurricane Rita produced an F3 tornado in Clayton, Louisiana on September 24, 2005.[129] Five more fatalities occurred in St. Mary's County, Maryland; Milford, Delaware; Naugatuck, Connecticut; North Conway, New Hampshire; and New York City due to falling trees. One woman died when her vehicle was swept downstream in a flooded area of Lehigh County, Pennsylvania,[130] and a child was found dead in Lansdale, Pennsylvania after going missing during the height of the storm.[131] One man drowned due to strong currents in Cape May, New Jersey.[132] New York City's power utility said it saw more outages from Isaias than from any storm except Hurricane Sandy in 2012. Damage estimates in excess of US$5.225 billion also made Isaias the costliest tropical cyclone to strike the Northeastern U.S. since Sandy.

Tropical Depression Ten

| Tropical depression (SSHWS) | |

| Duration | July 31 – August 2 |

|---|---|

| Peak intensity | 35 mph (55 km/h) (1-min); 1007 mbar (hPa) |

At 09:00 UTC July 30, the NHC began to monitor a broad area of low pressure associated with a tropical wave moving off the west coast of Africa southeast of the Cabo Verde Islands.[133] Throughout the day, thunderstorm activity increased in association with the system and became better organized, only to become disorganized again on the next day.[134][135] Contrary to predictions, the system rapidly re-organized, and at 21:00 UTC on July 31, the NHC began issuing advisories on Tropical Depression Ten.[136] The system showed signs of further organization, although it failed to achieve tropical storm status, as was previously predicted.[137] However, the NHC noted that the system may have briefly attained tropical storm status as some data showed tropical storm-force winds.[138] After maintaining its intensity for 12 hours, the cyclone began to weaken as it entered colder waters north of the Cabo Verde islands, and the system degenerated into a trough at 03:00 UTC on August 2.[139][140]

Tropical Storm Josephine

| Tropical storm (SSHWS) | |

| Duration | August 11 – August 16 |

|---|---|

| Peak intensity | 45 mph (75 km/h) (1-min); 1004 mbar (hPa) |

On August 7, the NHC began monitoring a tropical wave over the tropical Atlantic.[141] Slowly drifting westward, the wave initially struggled to become organized as it was placed within a relatively unfavorable environment.[142] However, the wave's circulation slowly became more defined while signs of convective organization became evident on satellite imagery. Soon enough the circulation became no longer elongated and the system was designated a tropical depression at 21:00 UTC, August 11.[143][144] Intensification was slow for the depression as dry air and wind shear prevented much development.[145] After two days of little change in intensity, the depression moved into more favorable conditions and intensified into Tropical Storm Josephine at 15:00 UTC, August 13.[146] Josephine became the earliest tenth named storm on record in the basin, exceeding Tropical Storm Jose of 2005 by nine days.[147][146] Josephine fluctuated in intensity due to little change in vertical wind shear slightly displacing the circulation from the deep convection.[148] Hurricane Hunter aircraft investigated the system later on August 14 and found that the storm's center had likely relocated further north in the afternoon hours.[149] Nonetheless, Josephine continued to move into increasingly hostile conditions as it started to pass north of the Leeward Islands.[150] As a result, the storm later weakened, becoming a tropical depression early on August 16, just north of the Virgin Islands.[151] The weakening cyclone's circulation became increasingly ill-defined, and Josephine eventually degenerated into a trough of low pressure later that day.[152]

Tropical Storm Kyle

| Tropical storm (SSHWS) | |

| Duration | August 14 – August 16 |

|---|---|

| Peak intensity | 50 mph (85 km/h) (1-min); 1000 mbar (hPa) |

On August 13, the NHC began to track an area of low pressure located over eastern North Carolina.[153] Warm water temperatures in the Atlantic allowed the system to rapidly organize, and at 21:00 UTC on August 14, the NHC designated the system as Tropical Storm Kyle.[154] It was the earliest eleventh named North Atlantic storm, beating the record of Hurricane Katrina in 2005 by 10 days.[155] By mid-day on August 15, Kyle had reached its peak intensity with maximum sustained winds of 50 mph (80 km/h) and a minimum pressure of 1000 mb (29.53 inHg); meanwhile, the circulation quickly started to become elongated.[156] As a result, the system began to rapidly lose its tropical characteristics with its circulation becoming asymmetric, ultimately leading to Kyle becoming a post-tropical cyclone early on August 16.[157] On August 20, Kyle's remnants were absorbed by extratropical Storm Ellen, a European windstorm which brought severe gales to the British Isles.[158][159]

Hurricane Laura

| Category 4 hurricane (SSHWS) | |

| Duration | August 20 – August 29 |

|---|---|

| Peak intensity | 150 mph (240 km/h) (1-min); 937 mbar (hPa) |

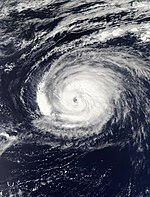

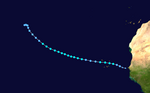

On August 16, the National Hurricane Center (NHC) began tracking a large tropical wave that had emerged off the West African coast, and began traversing across the Intertropical Convergence Zone (ITCZ) toward the Windward Islands.[160] En route to the Windward Islands, satellite imagery revealed that the system began to close off its low-level circulation center (LLCC) with convection firing up around it, and subsequently the NHC began issuing advisories on Tropical Depression Thirteen on August 20.[161] On the next day, Thirteen strengthened into Tropical Storm Laura, but was unable to strengthen any further, due to congestion of upper-level dry air as well as land interaction.[162] This made Laura the earliest twelfth named Atlantic storm, beating the previous record of Hurricane Luis of 1995 by eight days. As Laura moved just offshore of Puerto Rico, a possible center reformation occurred to the south of Puerto Rico allowing Laura to begin strengthening.[163][164] That same day, a shift eastward in the forecast track for Tropical Storm Marco indicated that Laura and Marco could make back-to-back landfalls in the area around Louisiana.[165][166] Early on August 23, Laura made landfall near San Pedro de Macorís, Dominican Republic, with 45 mph (75 km/h) winds.[167] On August 23, Laura attained large amounts of convection but still appeared ragged on satellite imagery, with the mountainous terrain of Hispaniola preventing it from strengthening.[168] Later that day, however, Laura managed to resume strengthening.[169] Early on August 25, Laura entered the Gulf of Mexico and became a Category 1 hurricane at 12:15 UTC on the same day.[170] After its upgrade to hurricane status, Laura began explosively intensifying, reaching Category 2 status early the next morning.[171] Laura's explosive intensification continued, and at 12:00 UTC on August 26, it became the first major hurricane of the season, with 1-minute sustained wind speeds of 115 mph (185 km/h).[172] Six hours later, it was further upgraded to Category 4 status, boasting winds of 140 mph (220 km/h).[173] Following its upgrade, Laura continued to rapidly strengthen due to favorable conditions, reaching a peak intensity with 1-minute sustained winds at 150 mph (240 km/h) and a minimum central pressure of 937 mbars, at 02:00 UTC on August 27, as the storm was nearing landfall.[174] At 06:00 UTC, Laura made landfall near Cameron, Louisiana, with 1-minute sustained winds of 150 mph (240 km/h) and a central pressure of 938 mbar (27.70 inHg), tying the 1856 Last Island hurricane as the strongest landfalling hurricane on record in the state of Louisiana since 1851.[175][4] Laura quickly weakened after moving inland, dropping to tropical storm status that evening over Northern Louisiana, before weakening into a tropical depression over Arkansas early the next morning.[176][177] Following its weakening to a depression, Laura turned eastwards, and by 09:00 UTC on August 29, Laura degenerated into a remnant low over northeastern Kentucky.[178]

As Laura passed through the Leeward Islands, the storm brought heavy rainfall to the islands of Guadeloupe and Dominica, as captured on radar.[179] The storm prompted the closing of all ports in the British Virgin Islands.[180] In Puerto Rico, Laura caused downed trees and flooding in Salinas.[181] Laura devastated southwestern Louisiana and southeastern Texas with Lake Charles, Louisiana being particularly hard hit. Laura killed 35 people in Hispaniola, including 4 in the Dominican Republic and 31 in Haiti, as well as 42 in the United States.

Hurricane Marco

| Category 1 hurricane (SSHWS) | |

| Duration | August 20 – August 25 |

|---|---|

| Peak intensity | 75 mph (120 km/h) (1-min); 991 mbar (hPa) |

The NHC began to track a tropical wave located over the central Tropical Atlantic at 00:00 UTC on August 16.[182] Initially hindered by its speed and unfavorable conditions in the eastern Caribbean, the wave began organizing once it reached the central Caribbean on August 19.[183] At 15:00 UTC on August 20, the NHC designated the wave as Tropical Depression Fourteen.[184] Intensification was initially slow, but the depression strengthened into Tropical Storm Marco at 03:00 UTC on August 22, becoming the earliest 13th named Atlantic storm, beating the previous record of 2005's Hurricane Maria and 2011's Tropical Storm Lee by 11 days.[nb 5][185] Marco passed just offshore of Honduras and, as a result of favorable atmospheric conditions, quickly intensified to an initial peak of 65 mph (105 km/h) and a pressure of 992 mb, with a characteristic eye beginning to form on radar.[186] Shortly afterwards, an increase in shear caused the system to become asymmetric and its pressure to rise slightly before it began to strengthen again, although its appearance remained disorganized.[187][188] After a Hurricane Hunters flight found evidence of sustained winds above hurricane force, Marco was upgraded to a Category 1 hurricane at 11:30 a.m. CDT on August 23, making it the third hurricane of the season.[189] Despite this, northeasterly vertical wind shear created by a trough situated northwest of Marco displaced its convection, exposing its low-level center, which caused the system to begin weakening significantly early on August 24.[190][191] At 23:00 UTC, Marco made landfall near the mouth of the Mississippi River as a weak tropical storm with winds at 40 mph (64 km/h) and a pressure of 1006 mb.[192] Marco degenerated into a remnant low just south of Louisiana at 09:00 UTC on August 25.[193]

Contrary to prior predictions, Marco's track was shifted significantly eastward late on August 22, as the system moved north-northeastward instead of north-northwestward, introducing the possibility of successive landfalls around Louisiana from both Laura and Marco.[194][186][166] However, Marco ultimately weakened faster than anticipated, and its landfall in Louisiana was much less damaging than initially feared, only causing around $35 million in damage. The storm indirectly killed 1 person in Chiapas, Mexico.[195]

Tropical Storm Omar

| Tropical storm (SSHWS) | |

| Duration | August 31 – September 5 |

|---|---|

| Peak intensity | 40 mph (65 km/h) (1-min); 1003 mbar (hPa) |

In the last few days of August, a cold front spawned a trough over Northern Florida and eventually a low-pressure area formed offshore of the southeast coast of the United States. The low rapidly organized as it drifted on top of the Gulf Stream, and was classified as Tropical Depression Fifteen at 21:00 UTC on August 31.[196] Moving generally northeastward away from North Carolina, the depression struggled to intensify in a marginally favorable environment with warm Gulf Stream waters being offset by high wind shear.[197] Eventually, satellite estimates revealed that the depression was intensifying and the system became consolidated enough to be upgraded to a tropical storm and as a result was given the name Omar at 21:00 UTC on September 1.[198] This event marked the earliest formation of the fifteenth named storm on record in the North Atlantic, exceeding the record of Hurricane Ophelia in 2005 by six days.[198] After maintaining its intensity for 24 hours, northwesterly wind shear of 50 knots weakened the storm back to a tropical depression.[199][200] Although wind shear continued to plague the system, Omar managed to remain a tropical cyclone.[201] Early on September 4, Omar fell to 30 mph amid the wind shear, and despite repeated forecasts for Omar to weaken further into a remnant low, Omar restrengthened back to 35 mph 12 hours later.[202][203] Early on September 5, Omar made a jog to the north; however, the center began to fully separate from the bursts of convection, and at 21:00 UTC that day, Omar degenerated into a remnant low.[204][205] The low moved northeastward, reaching Scotland on September 9.

While still a depression moving away from the United States, the storm brought life-threatening rip currents and swells to the coast of the Carolinas.[206]

Hurricane Nana

| Category 1 hurricane (SSHWS) | |

| Duration | September 1 – September 4 |

|---|---|

| Peak intensity | 75 mph (120 km/h) (1-min); 994 mbar (hPa) |

The NHC began to monitor a tropical wave over the Atlantic on August 27.[207] The wave moved into the southern Caribbean, where conditions were more favorable for development. The system managed to achieve gale-force winds, and at 15:00 UTC on September 1, advisories on Potential Tropical Cyclone Sixteen were initiated.[208] A closed circulation was found, and the system was upgraded to Tropical Storm Nana an hour later,[209] making it the earliest 14th named Atlantic storm on record, surpassing Hurricane Nate of 2005 by four days.[210] By 03:00 UTC the following day, the storm strengthened some more, obtaining 1-minute sustained winds of 60 mph (95 km/h).[211] Afterward, moderate northerly shear of 15 knots halted the trend and partially exposed the center of circulation.[212] The central pressure of Nana fluctuated between 996 and 1000 mbars (29.41 and 29.53 inHg) throughout the day on September 2, while sustained winds remained steady at 60 mph.[212] Early the next day, a slight center reformation and a burst of convection allowed Nana to quickly intensify into a hurricane at 03:00 UTC on September 3. Simultaneously, it reached its peak intensity with 1-minute sustained winds of 75 mph (120 km/h) and a minimum central pressure of 994 mbars (29.36 inHg).[213] Three hours later, Nana made landfall between Dangriga and Placencia in Belize near peak intensity.[214] Nana then began to rapidly weaken, dropping below hurricane status three hours after it made landfall,[215] and weakening to a tropical depression at 21:00 UTC.[216] Nana's low-level center then dissipated and the NHC issued their final advisory on the storm at 03:00 UTC on September 4.[217] The mid-level remnants eventually spawned Tropical Storm Julio in the eastern Pacific on September 5.[218][219]

Nana caused street flooding in the Bay Islands of Honduras.[220] Hundreds of acres of banana and plantation crops were destroyed in Belize, where a peak wind speed of 61 mph (98 km/h) was reported at a weather station in Carrie Bow Cay.[221] Total economic losses in Belize exceeded $20 million. Heavy amounts of precipitation also occurred in northern Guatemala.[222] Nana is the first hurricane to make landfall in Belize since Hurricane Earl in 2016.[223]

Hurricane Paulette

| Category 2 hurricane (SSHWS) | |

| Duration | September 7 – September 23 |

|---|---|

| Peak intensity | 105 mph (165 km/h) (1-min); 965 mbar (hPa) |

The NHC began to track a tropical wave located over Africa on August 30.[224] The wave organized and formed an area of low pressure on September 6, but convective activity remained disorganized.[225][226] In the early hours of September 7, it became more organized, and the NHC began issuing advisories for Tropical Depression Seventeen at 03:00 UTC on September 7.[227] Before becoming a tropical depression, the storm had previously struggled to organize due to short-lasting convective bursts with little consistency.[228] At 15:00 UTC on September 7, the NHC upgraded the system to Tropical Storm Paulette, the earliest 16th named Atlantic storm, breaking the previous record set by 2005's Hurricane Philippe by 10 days.[229][230] It moved generally west-northwestward over the warm Atlantic waters and it gradually intensified. At 15:00 UTC on September 8, Paulette reached its first peak intensity with 1-minute sustained winds of 65 mph (100 km/h) with a minimum central pressure of 995 mbar (29.39 inHg).[231] It held that intensity for 12 hours before an increase in wind shear weakened the storm.[232][233] On September 11, despite an estimated 40 knots (45 mph) of deep-layer southwesterly shear and dry air entrainment, Paulette began to reintensify.[234] The shear began to relax after that, allowing Paulette to become more organized and begin to form an eye.[235] At 03:00 UTC on September 13, Paulette was upgraded to hurricane status.[236] Dry air entrainment gave the storm a somewhat ragged appearance, but it continued to slowly strengthen as it approached Bermuda with its eye clearing out and its convection becoming more symmetric.[237] Paulette then made a sharp turn to the north and made landfall in northeastern Bermuda at 09:00 UTC on September 14 with 90 mph (150 km/h) winds and a 973 mb (28.74 inHg) pressure.[238] The storm then strengthened into a Category 2 hurricane as it accelerated northeast away from the island.[239] It reached its peak intensity at 18:00 UTC that day, with winds of 105 mph (170 km/h) and a pressure of 965 mb (28.50 inHg).[240] It was originally forecasted to become a major hurricane as it accelerated northeast, but increasing wind shear and dry air entrainment caused the storm's intensity to remain unchanged for the next day.[241] On the evening of September 15, it began to weaken and undergo extratropical transition,[242] which it completed the next day.[243]

After about five days of slow southward movement, the extratropical cyclone began to redevelop a warm core and its wind field shrank considerably. By September 22, it had redeveloped tropical characteristics and the NHC resumed issuing advisories shortly thereafter.[244] Between Paulette's initial formation and its reformation, seven other tropical or subtropical storms had formed in the Atlantic. It moved eastward over the next day, and became post-tropical for the second time in its lifespan early on September 23[245] and subsequently dissipated.

Trees and power lines were downed all over Bermuda, leading to an island-wide power outage.[246] Despite warnings of high rip current risk by the National Weather Service, a 60-year-old man drowned while swimming in Lavallette, New Jersey after being caught in rough surf produced by Hurricane Paulette.[247]

Tropical Storm Rene

| Tropical storm (SSHWS) | |

| Duration | September 7 – September 14 |

|---|---|

| Peak intensity | 50 mph (85 km/h) (1-min); 1000 mbar (hPa) |

On September 3, the NHC noted the possibility of another tropical wave to develop into a tropical depression.[248] On September 6, the wave emerged off the coast of Africa and subsequently began to rapidly organize, and at 09:00 UTC on September 7, it was upgraded to Tropical Depression Eighteen roughly halfway between Africa and Cabo Verde.[249] The depression strengthened just east of Cabo Verde, becoming Tropical Storm Rene just twelve hours later.[250] Rene became the earliest 17th named Atlantic storm, breaking the previous record set by Hurricane Rita in 2005 by 11 days.[251] Three hours later, Rene made landfall on Boa Vista Island with 1-minute sustained winds of 40 mph (65 km/h) and a pressure of 1001 mbars (29.56 inHg).[252] Although the storm lost some organization while moving through the Cabo Verde Islands, it remained a minimal tropical storm before it weakened to a tropical depression at 03:00 UTC on September 9.[253][254] The system restrengthened to a tropical storm twelve hours later while continuing to fight easterly wind shear.[255] It strengthened further, and attained its peak intensity with 1-minute sustained winds reaching 50 mph and the minimum central pressure dropping to 1000 mbars (29.53 inHg) at 15:00 UTC on September 10.[256] However, the continued effects of dry air and some easterly wind shear weakened the storm again 12 hours later.[257] As the storm continued west-northwestard, dry air eventually caused its convection to become sporadic and disorganized, and Rene was downgraded to a tropical depression at 15:00 UTC on September 12.[258] Bursts of deep convection allowed it to maintain tropical depression status for two more days before it began to rapidly unravel on September 14[259] and degenerated into a remnant low at 21:00 UTC the same day.[260] The low continued to move generally westward over the next two days before opening up into a surface trough at 17:30 UTC on September 16.[261][262][263][264]

A tropical storm warning was issued for the Cabo Verde Islands when advisory were first issued on the storm at 09:00 UTC on September 7.[249] Rene produced gusty winds and heavy rains across the islands, but no serious damage was reported.[265] The warning was discontinued at 21:00 UTC on September 8.[266]

Hurricane Sally

| Category 2 hurricane (SSHWS) | |

| Duration | September 11 – September 17 |

|---|---|

| Peak intensity | 105 mph (165 km/h) (1-min); 965 mbar (hPa) |

On September 10, the NHC began to monitor an area of disturbed weather over The Bahamas for possible development.[267] Over the next day, convection rapidly increased, became better organized, and formed a broad area of low-pressure on September 11.[268] At 21:00 UTC, the system had organized enough to be designated as Tropical Depression Nineteen.[269] At 06:00 UTC on September 12, the depression made landfall just south of Miami, Florida, with winds of 35 mph (55 km/h) and a pressure of 1007 mbar (29.74 inHg).[270] Shortly after moving into the Gulf of Mexico, the system strengthened into Tropical Storm Sally at 18:00 UTC the same day[271] and became the earliest 18th named Atlantic storm, surpassing the previous record set by Hurricane Stan in 2005 by 20 days.[272] Northwesterly shear caused by an upper-level low caused the system to have a sheared appearance, but it continued to strengthen as it gradually moved north-northwestward.[273] Sally began to go through a period of rapid intensification around midday on September 14. Its center reformed under a large burst of deep convection and it strengthened from a 65 mph (105 km/h) tropical storm to a 90 mph (140 km/h) Category 1 hurricane in just one and a half hours.[274][275] It continued to gain strength and became a Category 2 hurricane later that evening.[276] However, upwelling due to its slow movement as well increasing wind shear weakened Sally back down to Category 1 strength early the next day.[277] It continued to steadily weaken as it moved slowly northwest then north, although its pressure continued to fall.[278] However, as Sally approached the coast, its eye quickly became better defined and it abruptly began to reintensify.[279] By 05:00 UTC on September 15, it had become a Category 2 hurricane again.[280] At around 09:45 UTC, the system made landfall at peak intensity near Gulf Shores, Alabama with winds of 105 mph (165 km/h) and a pressure of 965 mbars (28.50 inHg).[281][282] The storm rapidly weakened as it moved slowly inland, weakening to a Category 1 hurricane at 13:00 UTC[283] and to a tropical storm at 18:00 UTC.[284] It further weakened to a tropical depression at 03:00 UTC on September 17[285] before degenerating into a remnant low at 15:00 UTC.[286]

A tropical storm watch was issued for the Miami metropolitan area when the storm first formed, while numerous watches and warnings were issued as Sally approached the U.S. Gulf Coast. Several coastline counties and parishes on the Gulf Coast were evacuated. In South Florida, heavy rain led to localized flash flooding while the rest of peninsula saw continuous shower and thunderstorm activity due to asymmetric structure of Sally. The storm made landfall on Gulf Shores, Alabama on the 16 year anniversary of Hurricane Ivan making landfall on the same location in 2004. The area between Mobile, Alabama and Pensacola, Florida took the brunt of the storm with widespread wind damage, storm surge flooding, and over 20 inches (51 cm) of rainfall which peaked at 30 inches at NAS Pensacola. Several tornadoes touched down as well.[287] Eight people were killed and damage estimates were at least $5 billion.[288]

Hurricane Teddy

| Category 4 hurricane (SSHWS) | |

| Duration | September 12 – September 23 |

|---|---|

| Peak intensity | 140 mph (220 km/h) (1-min); 945 mbar (hPa) |

The NHC began to monitor a tropical wave over Africa at 00:00 UTC on September 7.[289] The wave entered the Atlantic Ocean on September 10, and began to organize.[290] At 21:00 UTC on September 12, the NHC designated the disturbance as Tropical Depression Twenty.[291] It struggled to organize for over a day due to its large size and moderate wind shear.[292] After the shear decreased, the system became better organized and strengthened into Tropical Storm Teddy at 09:00 UTC on September 14, making it the earliest 19th Atlantic tropical / subtropical storm on record, beating the unnamed 2005 Azores subtropical storm by 20 days.[293][294] It continued to intensify as it became better organized, with an eye beginning to form late on September 15.[295] It then rapidly intensified into a hurricane around 06:00 UTC the next day.[296] The storm continued to intensify, becoming a Category 2 hurricane later that day.[297] However, some slight westerly wind shear briefly halted intensification and briefly weakened the storm to a Category 1 at 03:00 UTC on September 17.[298] When the shear relaxed, the storm rapidly reintensified into the second major hurricane of the season at 15:00 UTC that day.[299] Teddy further strengthened into a Category 4 hurricane six hours later, reaching its peak intensity of 140 mph (220 km/h) and a pressure of 945 mb (27.91 inHg).[300] Internal fluctuation and an eyewall replacement cycle caused the storm to weaken slightly to a Category 3 hurricane at 09:00 UTC on September 18.[301] Soon after, Teddy briefly restrengthened into a Category 4 hurricane before another eyewall replacement cycle weakened it again.[302][303] Continued internal fluctuations caused the eye to nearly dissipate and Teddy weakened below major hurricane status at 12:00 UTC on September 20.[304]

Teddy continued moving north, weakening to a Category 1 hurricane as it began to merge with a trough late on September 21. [305] A Hurricane Hunters flight found that Teddy had strengthened a bit, due to a combination of baroclinic energy infusion from the trough and warm oceanic waters from the Gulf Stream and it was upgraded back to Category 2 status.[306] Teddy also doubled in size as a result of merging with the trough. The hurricane kept expanding and started an extratropical transition while it neared Nova Scotia's south coast; although Teddy appeared to be a post-tropical cyclone, Hurricane Hunters also found a warm core in Teddy's center.[307] However, it weakened back to a Category 1 hurricane before transitioning to a post-tropical cyclone at 00:00 UTC on September 23.[308] Post-Tropical Cyclone Teddy made landfall near Ecum Secum, Nova Scotia approximately 12 hours later with maximum sustained winds near 65 mph (100 km/h) and a minimum central pressure of 964 mbar (28.47 inches).[308] It then moved rapidly north-northeastward across the Gulf of Saint Lawrence to the west of Newfoundland as a decaying extratropical low.[309]

On September 18, a man and a woman drowned in the waters off La Pocita Beach in Loíza, Puerto Rico due to the rip currents and churning waves that Teddy has been causing in the north of the Lesser and Greater Antilles.[310][311] Another person drowned due to rip currents in New Jersey.[312]

Tropical Storm Vicky

| Tropical storm (SSHWS) | |

| Duration | September 14 – September 17 |

|---|---|

| Peak intensity | 50 mph (85 km/h) (1-min); 1000 mbar (hPa) |

In the early hours of September 11, a tropical wave moved off the coast of West Africa.[313] The disturbance steadily organized, and the NHC issued a special advisory to designate the system as Tropical Depression Twenty-One at 10:00 UTC on September 14.[314] The depression strengthened into Tropical Storm Vicky five hours later based on scatterometer data, becoming the earliest 20th tropical / subtropical storm on record in an Atlantic hurricane season, surpassing the old mark of October 5, which was previously set by Tropical Storm Tammy in 2005.[315][316] It was also the first V-named Atlantic storm since 2005's Hurricane Vince.[317] Despite extremely strong shear removing all but a small convective cluster to the northeast of its center, Vicky intensified further, reaching its peak intensity with 1-minute sustained winds of 50 mph (85 km/h) and a pressure of 1000 mbar (29.53 inHg) at 03:00 UTC on September 15.[318][319] Six hours later, Vicky's pressure rose, but its winds continued to stay at 50 mph into the next day despite over 50 knots (60 mph, 95 km/h) of wind shear.[320][321][322] Eventually, the shear began to take its toll on Vicky, and Vicky's winds began to fall.[323] It weakened into a tropical depression at 15:00 UTC on September 17 before degenerating into a remnant low six hours later.[324][325] The low continued westward producing weak disorganized convection before opening up into a trough late on September 19 and dissipating the next day.[326][327][328]

The tropical wave that spawned Tropical Storm Vicky produced flooding in the Cabo Verde Islands less than a week after Tropical Storm Rene moved through the region. One person was killed in Praia on September 12 from the tropical wave.[329][330]

Tropical Storm Beta

| Tropical storm (SSHWS) | |

| Duration | September 17 – September 23 |

|---|---|

| Peak intensity | 60 mph (95 km/h) (1-min); 994 mbar (hPa) |

On September 10, the NHC began to monitor a trough of low pressure that had formed over the northeastern Gulf of Mexico.[331] Development of the system was not expected at the time due to strong upper-level winds produced by Hurricane Sally.[332] The disturbance nonetheless persisted, moving southwestward into the southwestern Gulf of Mexico where it began to organize as Sally moved away into the Southeastern United States early on September 16.[333] The next day, hurricane hunters found a closed circulation, and as thunderstorms persisted near the center, the NHC initiated advisories on Tropical Depression Twenty-Two at 23:00 UTC on September 17.[334] At 21:00 UTC on September 18, the system strengthened into Tropical Storm Beta,[335] becoming the earliest 23rd tropical / subtropical storm on record in an Atlantic hurricane season,[336] surpassing the old mark of October 22, which was previously set by Tropical Storm Alpha in 2005. Although affected by wind shear and dry air, the storm continued to intensify, reaching a peak intensity of 60 mph (95 km/h) and a pressure of 994 mb (29.36 inHg) at 15:00 UTC on September 19, with a brief mid-level eye feature visible on radar imagery.[337] [338] However, it became nearly stationary after turning westward over the Gulf of Mexico.[339] This caused upwelling and the continued negative effects of dry air and wind shear caused the storm to become disorganized.[340] As Beta approached the Texas coast, it weakened some before making landfall on the Matagorda Peninsula at 04:00 UTC on September 22 with winds of 45 mph (75 km/h) and a pressure of 999 mb (29.50 inHg).[341] Afterwards, Beta weakened some more, falling to tropical depression status at 15:00 UTC.[342] It then became nearly stationary again before turning east and weakening some more, causing the NHC to issue their final advisory and giving future advisory responsibilities to the Weather Prediction Center (WPC).[343][344] It transitioned to a remnant low at 03:00 UTC on September 23.[345]

Beta caused extensive flooding of streets and freeways of Houston, and the intense rainfall caused over 100,000 gallons of domestic wastewater to spill in five locations in the city. On September 22, a fisherman was reported missing in Brays Bayou, and four hours later, the Houston Police Department discovered his body.[346]

Tropical Storm Wilfred

| Tropical storm (SSHWS) | |

| Duration | September 18 – September 21 |

|---|---|

| Peak intensity | 40 mph (65 km/h) (1-min); 1007 mbar (hPa) |

On September 13, the NHC began to monitor a tropical wave over Africa for possible development.[347] The wave subsequently emerged over the eastern Atlantic and began to slowly organize as it moved westward, although it failed to obtain a well-defined low-level circulation (LLC).[348] Nonetheless, at 15:00 UTC on September 18, an LLC was found and, as the system already had gale force winds, was designated Tropical Storm Wilfred.[349] Wilfred became the earliest 21st tropical / subtropical storm on record in an Atlantic hurricane season, surpassing the old mark of October 8, which was previously set by Hurricane Vince in 2005,[350] and is only the second "W" named storm in the Atlantic (joining 2005's Hurricane Wilma) since naming began in 1950.[351] Located at a relatively low latitude, Wilfred remained weak and changed little in appearance due to wind shear and unfavorable conditions caused by the outflow of nearby Hurricane Teddy.[352] As a result, Wilfred failed to strengthen further, subsequently weakening to a tropical depression at 15:00 UTC on September 20.[353] Wilfred eventually degenerated into a trough at 03:00 UTC on September 21.[354]

Subtropical Storm Alpha

| Subtropical storm (SSHWS) | |

| Duration | September 18 – September 19 |

|---|---|

| Peak intensity | 50 mph (85 km/h) (1-min); 996 mbar (hPa) |

At 06:00 UTC on September 15, the NHC, together with Météo France, began tracking a non-tropical low pressure area north of 48°N, several hundred miles north of the Azores.[355] It was given a low chance of development as it moved southeast.[356] Over the next few days, it organized while the extratropical system surrounding it gradually weakened, although its proximity and fast movement towards the coast caused the NHC to lower its chances to development.[348] Early on September 18, the system started to rapidly become better defined and the NHC designated it as Subtropical Storm Alpha at 16:30 UTC.[357] Alpha made landfall just north of Lisbon, Portugal, at 18:30 UTC, becoming the first recorded tropical or subtropical cyclone to make landfall in mainland Portugal.[358] After landfall, the storm rapidly weakened, becoming a remnant low over the district of Viseu in Portugal at 03:00 UTC on September 19.[359]

Alpha is the earliest 22nd tropical / subtropical storm,[336] beating Wilma of 2005 by 29 days, and marked the second time in recorded history (joining 2005) that the main naming list has been exhausted and Greek letters were used. Additionally, Alpha overtook Tropical Storm Christine of 1973 as the easternmost-forming tropical or subtropical cyclone on record in the Atlantic. Alpha was the third confirmed tropical or subtropical cyclone to make landfall in mainland Europe, following a hurricane in Spain in 1842 and Hurricane Vince (as a tropical depression) in 2005.[360]

In preparation for Alpha on September 18, orange warnings were raised for high wind and heavy rain in Coimbra District and Leiria District of Portugal.[361] Alpha and its associated low produced extensive wind damage, spawned at least two tornadoes, and caused extreme street flooding.[362][363] In Spain, the front associated with Alpha caused a train to derail in Madrid (no one was seriously injured), while lightning storms on Ons Island caused a forest fire. A woman died in Calzadilla after a roof collapsed.[363]

Tropical Storm Gamma

| Tropical storm (SSHWS) | |

| Duration | October 2 – October 6 |

|---|---|

| Peak intensity | 70 mph (110 km/h) (1-min); 980 mbar (hPa) |