Ashvins

| Ashvins | |

|---|---|

Gods of Health and Medicine; The Divine Physicians of the Gods | |

| |

| Affiliation | Devas |

| Mount | Golden Chariot |

| Genealogy | |

| Parents | Surya and Sanjna[1] |

| Consort | Sūryā (the daughter of the Sun)[2][3] |

| Children | |

| Equivalents | |

| Greek | Dioskuri[4] |

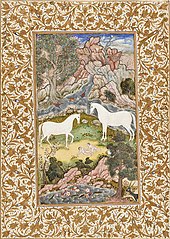

The Aśvins, or Ashwini Kumaras (Vedic Sanskrit: अश्विन्, aśvin, dual aśvinau; "horse possessors"; also spelled Ashvins),[5] are twin Vedic gods. The twin deities are associated with the dawn, medicine, and sciences in Hindu mythology.[6] They are described as youthful divine twin horsemen in the Rigveda, travelling in a chariot drawn by horses that are never weary.[7] They are known as guardian deities that safeguard and rescue people by aiding them in various situations.[8]

Origin

The Aśvins are an instance of the Proto-Indo-European divine horse twins.[9][10][7] Reflexes in other Indo-European historics include the Baltic Ašvieniai, the Greek Castor and Pollux; and possibly the English Hengist and Horsa, and the Welsh Bran and Manawydan.[9] The first mention of the Nasatya twins is from the Mitanni documents of the second millennium BCE, where they are invoked in a treaty between Suppiluliuma and Shattiwaza, respectively kings of the Hittites and the Mitanni.[11]

Etymology and epithets

In the Rigveda, the Aśvins are always referred to in the dual, and do not have individual names,[7] although Vedic texts differentiate between the two Aśvins: "one of you is respected as the victorious lord of Sumakha, and the other as the fortunate son of heaven" (RV 1.181.4). They are called several times divó nápātā, "grandsons of Dyaús (the sky-god)".[12]

The twin gods are also referred to as Nā́satyā (possibly "saviours"; a derivate of nasatí, "safe return home"), a name that appears 99 times in the Rigveda.[12] The epithet probably derives from the Proto-Indo-European root *nes- ("to return home (safely)"), with cognates in the Avestan Nā̊ŋhaiθya, the name of a demon, as a result of a Zoroastrian religious reformation that degraded the status of prior deities, in the Greek hero Nestor, and in the Gothic verb nasjan ("save, heal").[5][13]

In the Mahabharata, the Aśvins are often called the Nasatyas or Dasras. Sometimes one of them is referred to as Nasatya and one as Dasra.[14]

Associations

The Aśvins are often associated with rescuing mortals and bringing them back to life.[5] Rebha was bound, stabbed, and cast into the waters for nine days and ten nights before being saved by the twins. He was explicitly described as "dead" (mamṛvā́ṃsam) when the twins "raised (him) up" (úd airayatam) to save him (RV 10.39.9). Similarly, Bhujyu was saved after his father or evil companions abandoned him at sea, when the twins “[brought] (him) home from the dead ancestors” (niváhantā pitṛ́bhya ā́, 1.119.4).[5] The Rigveda also describes the Aśvins as "bringing light": they gave "light-bringing help" (svàrvatīr…ūtī́r, 1.119.8) to Bhujyu, and "raised (Rebha) up to see the sun" (úd…aírayataṃ svàr dṛśé, 1.112.5).[5][7] The Aśvins also raised up Vandana, rescued Atri from a fissure in the earth and its heat, found Viṣṇāpū and returned him to his father, restored the youth of Cyavāna and Kali, brought Kamadyū as a wife for Vimada, gave a son to Vadhrimatī (whose husband was a steer), restored the eyesight of Ṛjrāśva, replaced the foot of Viśpalā with a metal one, made the cow Śayu give milk, gave a horse to Pedu, and put a horse’s head on Dadhyañc.[15]

The Aśvins are associated with honey, which was likely what was offered to them in a sacrifice. They are the chief deities in the Pravargya rite, in which they are offered hot milk. They are also associated with the morning pressing of Soma, because they are dual deities, along with Indra-Vāyu and Mitra-Varuṇa. They also are the last deities to receive Soma in the Atirātra, or Overnight Soma Ritual.[16]

The Aśvins are invoked at dawn, the time of their principal sacrifice, and have a close connection with the dawn goddess, Uṣas: she is bidden to awaken them (8.9.17), they follow her in their chariot (8.5.2), she is born when they hitch their steeds (10.39.12), and their chariot is once said to arrive before her (1.34.10).[5] They are consequently associated with the "return from darkness": the twins are called “darkness slayers” (tamohánā, 3.39.3), they are invoked with the formula "you who have made light for mankind" (yā́v…jyótir jánāya cakráthuḥ, 1.92.17), and their horses and chariot are described as "uncovering the covered darkness" (aporṇuvántas táma ā́ párīvṛtam, 4.45.2).[5]

The chariot of the Aśvins is repeatedly mentioned in the Rigveda. Their chariot has three chariot-boxes, three wheels, three turnings, and three wheel rims. The emphasis on the number 3 is symbolized in the sacrifice with its three soma pressings. The chariot is pulled by bulls, buffaloes, horses, birds, geese, and falcons. The chariot allows the Aśvins to be quick and mobile and travel to a number of places, which is necessary to fulfill their role of rescuing people. Sūryā, the daughter of the Sun, is sometimes mentioned as the wife of the Aśvins, and she rides with them in their chariot.[8]

Rigveda

The Aśvins are mentioned 398 times in the Rigveda,[5] with more than 50 hymns specifically dedicated to them: 1.3, 1.22, 1.34, 1.46–47, 1.112, 1.116–120, 1.157–158, 1.180–184, 2.20, 3.58, 4.43–45, 5.73–78, 6.62–63, 7.67–74, 8.5, 8.8–10, 8.22, 8.26, 8.35, 8.57, 8.73, 8.85–87, 10.24, 10.39–41, 10.143.[7]

Your chariot, o Aśvins, swifter than mind, drawn by good horses, comes to the clans.

By which (chariot) you go to the home of the good ritual performer, by that, o men, travel your course to us.

You free Atri, the seer of the five peoples, from narrow straits, from the earth cleft along with his band, o men—confounding the wiles of the merciless Dasyu, driving them out, one after another, o bulls.

O Aśvins—you men, you bulls—by the wondrous powers you draw back together the seer Rebha, who bobbed away in the waters, like a horse hidden by those of evil ways. Your ancient deeds do not grow old.— 1.117.2–4, in The Rigveda, translated by Stephanie W. Jamison (2014)[17]

Puranas and Mahabharata

Later Hindu texts like the Mahabharata and the Puranas, relate that the Ashwini Kumar twins, who were Raja -Vaidya (royal physicians) to the Devas during Vedic times, first prepared the Chyawanprash formulation for Rishi Chyavana at his Ashram on Dhosi Hill near Narnaul, Haryana, India, hence the name Chyawanprash.[18] In the epic Mahabharata, King Pandu's wife Madri is granted a son by each Ashvin and bears the twins Nakula and Sahadeva who, are known as the Pandavas.[19]

References

- ^ Singh, Nagendra Kumar (1997), Encyclopaedia of Hinduism, vol. 44, Anmol Publications, pp. 2605–19, ISBN 81-7488-168-9.

- ^ Kramisch, Stella; Miller, Barbara (1983). Exploring India's Sacred Art. Shri Jainendra Press A-45, Naraina Industrial Area, Phase I, New Delhi-110 028, India: University of Pennsylvania Press, Indira Gandhi National Centre for the Arts, Motilal Banarsidass Publishers Private Limited. p. 171. ISBN 81-208-1208-X.

{{cite book}}: Check|isbn=value: checksum (help)CS1 maint: location (link) - ^ Jamison, Stephanie W. (2014). The Rigveda: The Earliest Religious Poetry of India. Oxford University Press. p. 48. ISBN 9780199370184.

- ^ West, Martin L. (2007). Indo-European Poetry and Myth. Oxford, England: Oxford University Press. pp. 186–191. ISBN 978-0-19-928075-9.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Frame 2009.

- ^ Wise, Thomas (1860). Commentary on the Hindu System of Medicine. Trübner.

- ^ a b c d e West 2007, p. 187. sfn error: multiple targets (2×): CITEREFWest2007 (help)

- ^ a b Jamison, Stephanie W. (2014). The Rigveda: The Earliest Religious Poetry of India. Oxford University Press. p. 48. ISBN 9780199370184.

- ^ a b Mallory & Adams 2006, p. 432.

- ^ Puhvel, Jaan (1987). Comparative Mythology. Baltimore, Maryland: Johns Hopkins University Press. pp. 58–61. ISBN 0-8018-3938-6.

- ^ KBo 1 1. Gary M. Beckman (1 January 1999). Hittite Diplomatic Texts. Scholars Press. p. 53.. Excerpt http://www.heritageinstitute.com/zoroastrianism/ranghaya/suppiluliuma_shattiwaza_treaty.htm

- ^ a b Parpola 2015, pp. 109–110.

- ^ Ahmadi, Amir (2015). "Two Chthonic Features of the Daēva Cult in Historical Evidence". History of Religions. 54 (3): 348. doi:10.1086/679000. ISSN 0018-2710. JSTOR 10.1086/679000. S2CID 162230518.

- ^ Thadani, N.v. The Mystery of the Mahabharata: Vol. I. India Research Press. p. 362.

- ^ Jamison, Stephanie W. (2014). The Rigveda: The Earliest Religious Poetry of India. Oxford University Press. p. 48. ISBN 9780199370184.

- ^ Jamison, Stephanie W. (2014). The Rigveda: The Earliest Religious Poetry of India. Oxford University Press. p. 47. ISBN 9780199370184.

- ^ Jamison, Stephanie W. (2014). The Rigveda: The Earliest Religious Poetry of India. Oxford University Press. pp. 272–273. ISBN 9780199370184.

- ^ Panda, H; Handbook on Ayurvedic Medicines With Formulae, Processes And Their Uses, 2004, p10 ISBN 978-81-86623-63-3

- ^ Hindu World: An Encyclopedic Survey of Hinduism. Volume II M-Z. Benjamin Walker. Routledge. 2019. Entry: "Pandava"

Bibliography

- Frame, Douglas (2009). "Hippota Nestor - 3. Vedic". Center for Hellenic Studies.

- Mallory, James P.; Adams, Douglas Q. (2006). The Oxford Introduction to Proto-Indo-European and the Proto-Indo-European World. Oxford, England: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-929668-2.

- Parpola, Asko (2015). The Roots of Hinduism: The Early Aryans and the Indus Civilization. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-022693-0.

- West, Martin L. (2007). Indo-European Poetry and Myth. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-928075-9.

Further reading

- Parva, Paushya. "Section III (Paushya Parva". Sacred Texts. pp. 32–33. Retrieved 1 November 2013.

- Dictionary of Hindu Lore and Legend (ISBN 0-500-51088-1) by Anna L. Dallapiccola

- BOSCH, F. D. K. "DE AŚVIN-GODEN EN DE EPISCHE TWEELINGEN IN DE OUDJAVAANSE KUNST EN LITERATUUR." Bijdragen Tot De Taal-, Land- En Volkenkunde 123, no. 4 (1967): 427-41. Accessed June 23, 2020. www.jstor.org/stable/27860895.

- Chakravarty, Uma. “THE AŚVINS: AN INCARNATION OF THE UNIVERSAL TWINSHIP MOTIF.” Annals of the Bhandarkar Oriental Research Institute, vol. 70, no. 1/4, 1989, pp. 137–143. JSTOR, www.jstor.org/stable/41693465. Accessed 28 Apr. 2020.

- JAMISON, S. W. Indo-Iranian Journal, vol. 45, no. 4, 2002, pp. 347–350. JSTOR, www.jstor.org/stable/24664156. Accessed 28 Apr. 2020.

- Mitra, Jyotir. “ASHVINS, THE TWIN CELESTIAL PHYSICIANS, AND THEIR MEDICAL SKILL.” Proceedings of the Indian History Congress, vol. 45, 1984, pp. 220–228., www.jstor.org/stable/44140202. Accessed 28 Apr. 2020.

- Parpola, Asko. (2015). The Aśvins as Funerary Gods. In: The Roots of Hinduism. pp. 117-129. 10.1093/acprof:oso/9780190226909.003.0011.