Effects of climate change: Difference between revisions

m Dating maintenance tags: {{Cn}} |

Notagainst (talk | contribs) →Sense of crisis: Add extinction rebellion |

||

| Line 642: | Line 642: | ||

=== Sense of crisis === |

=== Sense of crisis === |

||

In response to the threat posed by global warming, in August 2018, [[Greta Thunberg]] began demonstrating outside the Swedish parliament to bring attention to the |

In response to the threat posed by global warming, in May 2018 [[Roger Hallam]] and [[Gail Bradbrook]] started the civil disobedience movement, [[Extinction Rebellion]], to try and compel government action to address the problem. In August 2018, [[Greta Thunberg]] began demonstrating outside the Swedish parliament to bring attention to the issue, calling it an 'existential crisis',<ref>[https://www.politico.eu/article/global-climate-icon-finds-that-political-change-is-complicated/ Climate icon Greta Thunberg finds that political change is ‘complicated’], Politico, 16 April 2019 </ref> galvanising a world-wide movement, especially among young people, towards the need for immediate action.<ref> [https://www.theguardian.com/environment/2019/aug/30/greta-thunberg-un-climate-protest-new-york Hundreds of young people join Greta Thunberg in climate protest outside UN], the Guardian, 30 August 2019</ref><ref> [https://www.independent.co.uk/environment/greta-thunberg-trump-climate-change-denial-environment-us-a9201521.html Greta Thunberg says Trump's 'extreme' climate change denial is helping environmental movement], The Independent, 13 November 2013</ref> To highlight concerns about global warming, in 2019 some media outlets began using the term ''[[climate crisis]]'' instead of climate change.<ref>[https://www.theguardian.com/environment/2019/may/17/why-the-guardian-is-changing-the-language-it-uses-about-the-environment Why the Guardian is changing the language it uses about the environment], The Guardian, 17 May 2019</ref> |

||

In November 2019, over 11,000 climate scientists added their names to a declaration<ref>[https://scientistswarning.forestry.oregonstate.edu/sites/sw/files/climate%20emergency%20Ripple%20et%20al.pdf World Scientists’ Warning of a Climate Emergency], In press with Bioscience Magazine </ref> published in the journal BioScience,<ref>World Scientists’ Warning of a Climate Emergency, William J Ripple, Christopher Wolf, Thomas M Newsome, Phoebe Barnard, William R Moomaw. BioScience, biz088, https://doi.org/10.1093/biosci/biz088. A correction has been published: |

In November 2019, over 11,000 climate scientists added their names to a declaration<ref>[https://scientistswarning.forestry.oregonstate.edu/sites/sw/files/climate%20emergency%20Ripple%20et%20al.pdf World Scientists’ Warning of a Climate Emergency], In press with Bioscience Magazine </ref> published in the journal BioScience,<ref>World Scientists’ Warning of a Climate Emergency, William J Ripple, Christopher Wolf, Thomas M Newsome, Phoebe Barnard, William R Moomaw. BioScience, biz088, https://doi.org/10.1093/biosci/biz088. A correction has been published: |

||

Revision as of 06:35, 1 January 2020

The effects of global warming include far-reaching and long-lasting changes to the natural environment, to ecosystems and human societies caused directly or indirectly by human emissions of greenhouse gases. It also includes the economic and social changes which stem from living in a warmer world and the responses to those changes.

Many physical impacts of global warming have already been observed, including extreme weather events, glacier retreat,[2] changes in the timing of seasonal events[2] (e.g., earlier flowering of plants),[3] sea level rise, and declines in Arctic sea ice extent.[4] The potential impact of global warming depends on the extent to which nations implement prevention efforts and reduce greenhouse gas emissions. Ocean acidification is not a consequence of global warming, but instead has the same cause: increasing atmospheric carbon dioxide.

Climate change has already impacted ecosystems and humans as well.[5] In combination with climate variability, it makes food insecurity worse in many places[6] and puts pressure on fresh water supply. This in combination with extreme weather events, leads to negative effects on human health. Rising temperatures threaten development because of negative effects on economic growth in developing countries.[6] The social impact of climate change will be further affected by society's efforts to prepare and adapt.[7][8] Global warming already contributes to mass migration in different parts of the world.[9][10]

Near-term climate change policies significantly affect long-term climate change impacts.[7][11] Stringent mitigation policies might be able to limit global warming (in 2100) to around 2 °C or below, relative to pre-industrial levels.[12] Without mitigation, increased energy demand and extensive use of fossil fuels[13] might lead to global warming of around 4 °C.[14][15] Higher magnitudes of global warming would be more difficult to adapt to,[16] and would increase the risk of negative impacts.[17]

Observed and future warming

Global warming refers to the long-term rise in the average temperature of the Earth's climate system. It is a major aspect of climate change, and has been demonstrated by the instrumental temperature record which shows global warming of around 1 °C since the pre-industrial period,[18] although the bulk of this (0.9°C) has occurred since 1970.[19] A wide variety of temperature proxies together prove that the 20th century was the hottest recorded in the last 2,000 years. Compared to climate variability in the past, current warming is also more globally coherent, affecting 98% of the planet.[20][21] The impact on the environment, ecosystems, the animal kingdom, society and humanity depends on how much more the Earth warms.[22]

The Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) Fifth Assessment Report concluded, "It is extremely likely that human influence has been the dominant cause of the observed warming since the mid-20th century."[23] This has been brought about primarily through the burning of fossil fuels which has led to a significant increase in the concentration of GHGs in the atmosphere.[24]

Emission scenarios

Individual consumers, corporate decision makers, the fossil fuel industries, government responses and the extent to which different countries agree to cooperate all have a profound impact on how much greenhouse gases the worlds emits. As the crisis and modelling techniques have evolved, the IPCC and other climate scientists have tried a number of different tools to estimate likely greenhouse gas emissions in the future.

Representative Concentration Pathways” (RCPs) were based on possible differences in radiative forcing occurring in the next 100 years but do not include socioeconomic “narratives” to go alongside them.[25] Another group of climate scientists, economists and energy system modellers took a different approach known as Shared Socioeconomic Pathways (SSPs); this is based on how socioeconomic factors such as population, economic growth, education, urbanisation and the rate of technological development might change over the next century. The SSPs describe five different trajectories which describe future climactic developments in the absence of new environmental policies beyond those in place today. They also explore the implications of different climate change mitigation scenarios.[26]

Warming projections

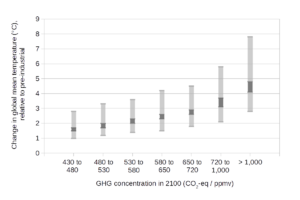

The range in temperature projections partly reflects the choice of emissions scenario, and the degree of "climate sensitivity".[27] The projected magnitude of warming by 2100 is closely related to the level of cumulative emissions over the 21st century (i.e. total emissions between 2000–2100).[28] The higher the cumulative emissions over this time period, the greater the level of warming is projected to occur.[28] Climate sensitivity reflects uncertainty in the response of the climate system to past and future GHG emissions.[27] Higher estimates of climate sensitivity lead to greater projected warming, while lower estimates lead to less projected warming.[29]

The IPCC's Fifth Report, released in 2014, states that relative to the average from year 1850 to 1900, global surface temperature change by the end of the 21st century is likely to exceed 1.5 °C and may well exceed 2 °C for all RCP scenarios except RCP2.6. It is likely to exceed 2°C for RCP6.0 and RCP8.5, and more likely than not to exceed 2°C for RCP4.5. The IPCC says the pathway with the highest greenhouse gas emissions, RCP 8.5, will lead to a temperature increase of about 4.3˚C by 2100.[30] Warming will continue beyond 2100 under all RCP scenarios except RCP2.6.[31]

The Climate Action Tracker also says mitigation policies currently in place around the world will result in about 3.0°C warming above pre-industrial levels. However, if current plans are not actually implemented, global warming is expected to reach 4.1°C to 4.8°C by 2100. CAT goes on to say there is a substantial gap between national plans and commitments and actual actions so far taken by governments around the world.[32]

Even if emissions were drastically reduced overnight, the warming process is irreversible because CO2 takes hundreds of years to break down, and global temperatures will remain close to their highest level for at least the next 1,000 years.[33][34]

Warming in context of Earth's past

One of the methods scientists use to predict the effects of human-caused climate change, is to investigate past natural changes in climate.[35] Scientists have used various "proxy" data to assess changes in Earth's past climate or paleoclimate.[36] Sources of proxy data include historical records such as tree rings, ice cores, corals, and ocean and lake sediments.[36] The data shows that recent warming has surpassed anything in the last 2,000 years.[37]

By the end of the 21st century, temperatures may increase to a level not experienced since the mid-Pliocene, around 3 million years ago.[38] At that time, models suggest that mean global temperatures were about 2–3 °C warmer than pre-industrial temperatures.[38] In the early Pliocene era, the global temperature was only 1-2 °C warmer than now, but sea level was 15–25 meters higher.[39][40]

Physical impacts

A broad range of evidence shows that the climate system has warmed.[42] Evidence of global warming is shown in the graphs (below right) from the US National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA). Some of the graphs show a positive trend, e.g., increasing temperature over land and the ocean, and sea level rise. Other graphs show a negative trend, such as decreased snow cover in the Northern Hemisphere, and declining Arctic sea ice, both of which are indicative of global warming. Evidence of warming is also apparent in living (biological) systems such as changes in distribution of flora and fauna towards the poles.[43]

Human-induced warming could lead to large-scale, abrupt and/or irreversible changes in physical systems.[44][45] An example of this is the melting of ice sheets, which contributes to sea level rise.[46] The probability of warming having unforeseen consequences increases with the rate, magnitude, and duration of climate change.[47]

Effects on weather

The main impact of global warming on the weather is an increase in extreme weather events such as heat waves, droughts, cyclones, blizzards and rainstorms. Of the 20 costliest climate and weather disasters that have occurred in the United States since 1980, eight have taken place since 2010, four of these in 2017 alone.[48] Such events will continue to occur more often and with greater intensity.[49] Episodes of intense precipitation contribute to flooding, soil erosion, landslides, and damage to structures and crops.[50]

Precipitation

Higher temperatures lead to increased evaporation and surface drying. As the air warms, its water-holding capacity also increases, particularly over the oceans. In general the air can hold about 7% more moisture for every 1 °C of temperature rise.[27] In the tropics, there’s more than a 10% increase in precipitation for a 1 °C increase in temperature.[53] Changes have already been observed in the amount, intensity, frequency, and type of precipitation. Extreme precipitation events are sometimes the result of atmospheric rivers - wide paths of atmospheric moisture composed of condensed water vapor.[54] Widespread increases in heavy precipitation have occurred even in places where total rain amounts have decreased.[55]

Projections of future changes in precipitation show overall increases in the global average, but with substantial shifts in where and how precipitation falls.[27] Projections suggest a reduction in rainfall in the subtropics, and an increase in precipitation in subpolar latitudes and some equatorial regions.[52] In other words, regions which are dry at present will in general become even drier, while regions that are currently wet will in general become even wetter.[52] This projection does not apply to every locale, and in some cases can be modified by local conditions.[52] Although increased rainful will not occur everywhere, models suggest most of the world will have a 16-24% increase in heavy precipitation intensity by 2100.[56]

Temperatures

Over most land areas since the 1950s, it is very likely that at all times of year both days and nights have become warmer due to human activities.[57] There may have been changes in other climate extremes (e.g., floods, droughts and tropical cyclones) but these changes are more difficult to identify.[57] Projections suggest changes in the frequency and intensity of some extreme weather events.[57] In the U.S. since 1999, two warm weather records have been set or broken for every cold one.[58][59]

Some changes (e.g. more frequent hot days) will probably be evident in the near term (2016–2035), while other near-term changes (e.g. more intense droughts and tropical cyclones) are more uncertain.[57]

Future climate change will include more very hot days and fewer very cold days.[57] The frequency, length and intensity of heat waves will very likely increase over most land areas.[57] Higher growth in anthropogenic GHG emissions would cause more frequent and severe temperature extremes.[60] If GHG emissions grow a lot (IPCC scenario RCP8.5), already dry regions may have more droughts and less soil moisture.[61] Over most of the mid-latitude land masses and wet tropical regions, extreme precipitation events will very likely become more intense and frequent.[57]

Heat waves

Global warming boosts the probability of extreme weather events such as heat waves[62][63] where the daily maximum temperature exceeds the average maximum temperature by 5 °C (9 °F) for more than five consecutive days.[64]

In the last 30–40 years, heat waves with high humidity have become more frequent and severe. Extremely hot nights have doubled in frequency. The area in which extremely hot summers are observed has increased 50-100 fold. These changes are not explained by natural variability, and are attributed by climate scientists to the influence of anthropogenic climate change. Heat waves with high humidity pose a big risk to human health while heat waves with low humidity lead to dry conditions that increase wildfires. The mortality from extreme heat is larger than the mortality from hurricanes, lightning, tornadoes, floods, and earthquakes together.[65]

Tropical cyclones

Global warming not only causes changes in tropical cyclones, it may also make some impacts from them worse via sea level rise. The intensity of tropical cyclones (hurricanes, typhoons, etc) is projected to increase globally, with the proportion of Category 4 and 5 tropical cyclones increasing. Furthermore, the rate of rainfall is projected to increase, but trends in the future frequency on a global scale are not yet clear.[66][67] Changes in tropical cyclones will probably vary by region.[66]

On land

Flooding

Warmer air holds more water vapor. When this turns to rain, it tends to come in heavy downpours potentially leading to more floods. A 2017 study found that peak precipitation is increasing between 5 and 10% for every one degree Celsius increase.[68] In the United States and many other parts of the world there has been a marked increase in intense rainfall events which have resulted in more severe flooding.[69] Estimates of the number of people at risk of coastal flooding from climate-driven sea-level rise varies from 190 million,[70] to 300 million or even 640 million in a worst-case scenario related to the instability of the Antarctic ice sheet.[71][72]

Wildfires

Prolonged periods of warmer temperatures typically cause soil and underbrush to be drier for longer periods, increasing the risk of wildfires. Hot, dry conditions increase the likelihood that wildfires will be more intense and burn for longer once they start.[73] Global warming has increased summertime air temperatures in California by over 3.5 degrees Fahrenheit such that the fire season (the time before the winter rains dampen the vegetation) has lengthened by 75 days over previous decades. As a result, since the 1980s, both the size and ferocity of fires in California have increased dramatically. Since the 1970s, the size of the area burned has increased fivefold while fifteen of the 20 largest fires in California have occurred since 2000.[74]

In Australia, the annual number of hot days (above 35°C) and very hot days (above 40°C) has increased significantly in many areas of the country since 1950. The country has always had bushfires but in 2019, the extent and ferocity of these fires increased dramatically.[75] For the first time catastrophic bushfire conditions were declared for Greater Sydney. New South Wales and Queensland declared a state of emergency but fires were also burning in South Australia and Western Australia.[76]

Cryosphere

The cryosphere is made up of those parts of the planet which are so cold, they are frozen and covered by snow or ice. This includes ice and snow on land such as the continental ice sheets in Greenland and Antarctica, as well as glaciers and areas of snow and permafrost; and ice found on water including frozen parts of the ocean, such as the waters surrounding Antarctica and the Arctic.[77] The cryosphere, especially the polar regions, is extremely sensitive to changes in global climate.[78]

Arctic sea ice began to decline at the beginning of the twentieth century but the rate is accelerating. Since 1979, satellite records indicate the decline in summer sea ice coverage has been about 13% per decade.[79][80] The thickness of sea ice has also decreased by 66% or 2.0 m over the last six decades with a shift from permanent ice to largely seasonal ice cover.[81] While ice-free summers are expected to be rare at 1.5 °C degrees of warming, they are set to occur at least once every decade at a warming level of 2.0 °C.[82]

Since the beginning of the twentieth century, there has also been a widespread retreat of alpine glaciers,[83] and snow cover in the Northern Hemisphere.[84] During the 21st century, glaciers[85] and snow cover are projected to continue their widespread retreat.[86] In the western mountains of North America, increasing temperatures and changes in precipitation are projected to lead to reduced snowpack.[87] The melting of the Greenland and West Antarctic ice sheets could contribute to sea level rise, especially over long time-scales (see the section on Greenland and West Antarctic Ice sheets).[46]

Changes in the cryosphere are projected to have social impacts.[88] For example, in some regions, glacier retreat could increase the risk of reductions in seasonal water availability.[89] Barnett et al. (2005)[90] estimated that more than one-sixth of the world's population rely on glaciers and snowpack for their water supply.

Oceans

Global warming is projected to have a number of effects on the oceans. Ongoing effects include rising sea levels due to thermal expansion and melting of glaciers and ice sheets, and warming of the ocean surface, leading to increased temperature stratification.[91] Other possible effects include large-scale changes in ocean circulation. The increase in ocean heat content is much larger than any other store of energy in the Earth's heat balance over the two periods 1961 to 2003 and 1993 to 2003, and accounts for more than 90% of the possible increase in heat content of the Earth system during these periods.[92] In 2019 a paper published in the journal Science found the oceans are heating 40% faster than the IPCC predicted just five years before.[93][94]

The oceans also serve as a sink for carbon dioxide, taking up much that would otherwise remain in the atmosphere, but increased levels of CO

2 have led to ocean acidification. Furthermore, as the temperature of the oceans increases, they become less able to absorb excess CO

2. The oceans have also acted as a sink in absorbing extra heat from the atmosphere.[95]: 4

Oxygen depletion

Warmer water cannot contain as much oxygen as cold water, so heating is expected to lead to less oxygen in the ocean. Other processes also play a role: stratification may lead to increases in respiration rates of organic matter, further decreasing oxygen content. The ocean has already lost oxygen, throughout the entire water column and oxygen minimum zones are expanding worldwide.[91] This has adverse consequences for ocean life.[96][97]

Ocean heat uptake

Ocean have taken up over 90% of the excess heat accumulated on Earth as a consequence of global warming.[98] The warming rate varies with depth: at a depth of a thousand meters the warming occurs at a rate of almost 0.4 °C per century (data from 1981-2019), whereas the warming rate at two kilometers depth is only half.[99] As well as having effects on ecosystems (e.g. by melting sea ice, affecting algae that grow on its underside), warming reduces the ocean's ability to absorb CO

2.[100] It is likely that ocean warming rate increased between 1993-2017 compared to the period starting in 1969.[101]

Sea level rise

The IPCC's Special Report on the Ocean and Cryosphere concluded that global mean sea level rose by 0.16 metres between 1901 and 2016.[103] The rate of sea level rise since the industrial revolution in the 19th century has been larger than the rate during the previous two thousand years (high confidence).[104]

Global sea level rise is accelerating, rising 2.5 times faster between 2006 and 2016 than it did during the 20th century.[105][106] Two main factors contribute to the rise. The first is thermal expansion: as ocean water warms, it expands. The second is from the melting of land-based ice in glaciers and ice sheets due to global warming.[107] Prior to 2007, thermal expansion was the largest component in these projections, contributing 70–75% of sea level rise.[108] As the impact of global warming has accelerated, melting from glaciers and ice sheets has become the main contributor.[109]

Even if emission of greenhouse gases stopped overnight, sea level rise will continue for centuries to come.[110] In 2015, a study by Professor James Hansen of Columbia University and 16 other climate scientists said a sea level rise of three metres could be a reality by the end of the century.[111] Another study by scientists at the Royal Netherlands Meteorological Institute in 2017 using updated projections of Antarctic mass loss and a revised statistical method also concluded that, although it was a low probability, a three-metre rise was possible.[112] Rising sea levels will put hundreds of millions of people at risk in low lying coastal areas in countries such as China, Bangladesh, India and Vietnam.[113]

Regional effects

Regional effects of global warming vary in nature. Some are the result of a generalised global change, such as rising temperature, resulting in local effects, such as melting ice. In other cases, a change may be related to a change in a particular ocean current or weather system. In such cases, the regional effect may be disproportionate and will not necessarily follow the global trend.

There are three major ways in which global warming will make changes to regional climate: melting or forming ice, changing the hydrological cycle (of evaporation and precipitation) and changing currents in the oceans and air flows in the atmosphere. The coast can also be considered a region, and will suffer severe impacts from sea level rise.

The Arctic, Africa, small islands and Asian megadeltas are regions that are likely to be especially affected by climate change.[116] Low-latitude, less-developed regions are at most risk of experiencing negative impacts due to climate change.[117] Developed countries are also vulnerable to climate change.[118] For example, developed countries will be negatively affected by increases in the severity and frequency of some extreme weather events, such as heat waves.[118] In all regions, some people can be particularly at risk from climate change, such as the poor, young children and the elderly.[116][117][119]

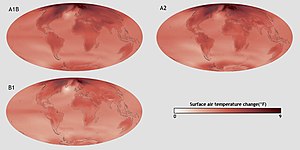

Projections of future climate changes at the regional scale do not hold as high a level of scientific confidence as projections made at the global scale.[120]: 9 It is, however, expected that future warming will follow a similar geographical pattern to that seen already, with greatest warming over land and high northern latitudes, and least over the Southern Ocean and parts of the North Atlantic Ocean.[121] Land areas warm faster than ocean, and this feature is even stronger for extreme temperatures. For hot extremes, regions with the most warming include Central and South Europe and Western and central Asia.[122]

On humans

The vulnerability and exposure of humans to climate change varies from one economic sector to another and will have different impacts in different countries. Wealthy industrialised countries, which have emitted the bulk of CO2 into the atmosphere have more resources and so are the least vulnerable to global warming.[123] Economic sectors that are likely to be affected include agriculture, human health, fisheries, forestry, energy, insurance, financial services, tourism, and recreation.[124] The quality and quantity of freshwater will likely be affected almost everywhere.

Food security

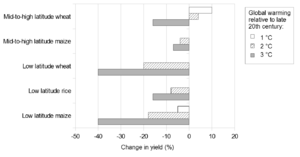

Climate change will impact agriculture and food production around the world due to the effects of elevated CO2 in the atmosphere, higher temperatures, altered precipitation and transpiration regimes, increased frequency of extreme events, and modified weed, pest, and pathogen pressure.[126] Climate change is projecting to negatively affect all four pillars of food security: not only how much food is available, but is also how easy the food is to access (prices), the quality of the food and how stable the food system is.[127]

Food availability

As of 2019, negative impacts have been observed for some crops in low-latitudes (maize and wheat), while positive impacts of climate change have been observed in some crops in high-latitudes (maize, wheat, and sugar beets).[129]

Using different methods to project future crop yields, a consistent picture emerges of global decreases in yield. Maize and soybean decrease with any warming, whereas rice and wheat production might peak at 3 °C of warming.[130]

In many areas, fisheries have already seen their catch decrease as a consequence of the effects of global warming and changes in biochemical cycles. In combination with overfishing, warming waters decrease the maximum catch potential.[131] Global catch potential is projected to reduce further in 2050 by less than 4% if emissions are reduced strongly, and by about 8% for very high future emissions, with growth in the Arctic Ocean.[132]

Other aspects of food security

Climate change impacts depends strongly on projected future social and economic development. Currently, an estimated 831 million people are undernourished.[133] Under a high emission scenario (RCP6.0), cereals are projected to become 1-29% more expensive in 2050 depending on the socioeconomic pathway, particularly affecting low-income consumers.[133] Compared to a no climate change scenario, this would put between 1-181 million extra people at risk of hunger.[133]

While CO2 is expected to be good for crop productivity at lower temperatures, it does reduce the nutritional values of crops, with for instance wheat having less protein and some minerals.[134] It is difficult to project the impact of climate change on volatility of food prices and use, but most models projecting the future indicate that prices will become more volatile.[135]

Droughts and agriculture

Some evidence suggests that droughts have been occurring more frequently because of global warming and they are expected to become more frequent and intense in Africa, southern Europe, the Middle East, most of the Americas, Australia, and Southeast Asia.[136] However, other research suggests that there has been little change in drought over the past 60 years.[137] Their impacts are aggravated because of increased water demand, population growth, urban expansion, and environmental protection efforts in many areas.[138] Droughts result in crop failures and the loss of pasture grazing land for livestock.[139]

Water security

A number of climate-related trends have been observed that affect water resources. These include changes in precipitation, the cryosphere and surface waters (e.g., changes in river flows).[140] Observed and projected impacts of climate change on freshwater systems and their management are mainly due to changes in temperature, sea level and precipitation variability.[141] Changes in temperature are correlated with variability in precipitation because the water cycle is reactive to temperature.[142] Temperature increase cause a shift in precipitation patterns. Excessive precipitation patterns lead to excessive sediment deposition, nutrient pollution, and concentration of minerals in aquifers.

The rising global temperature will cause sea level rise and will extend areas of salinization of groundwater and estuaries, resulting in a decrease in freshwater availability for humans and ecosystems in coastal areas. The exposure of rising sea level will push the salt gradient into freshwater deposits and will eventually pollute freshwater sources. In the 2014 fifth IPCC assessment report it was concluded that:

- Water resources are projected to decrease in most dry subtropical regions and mid-latitudes, but increase in high latitudes. As streamflow becomes more variable, even regions with increased water resources can experience additional short-term shortages.[143]

- Per degree warming, a model average of 7% of the world population is expected to have at least 20% less renewable water resource.[144]

- Climate change is projected to reduce water quality before treatment. Even after conventional treatments, risks remain. The quality reduction is a consequence of higher temperatures, more intense rainfall, droughts and disruption of treatment facilities during floods.[144]

- Droughts that stress water supply system are expected to increase in southern Europe and the Mediterranean region, central Europe, central and southern North America, Central America, northeast Brazil, and southern Africa.[145]

Health

Humans are exposed to climate change through changing weather patterns (temperature, precipitation, sea-level rise and more frequent extreme events) and indirectly through changes in water, air and food quality and changes in ecosystems, agriculture, industry and settlements and the economy (Confalonieri et al., 2007:393).[146]

A study by the World Health Organization (WHO, 2009)[147] estimated the effect of climate change on human health. Not all of the effects of climate change were included in their estimates, for example, the effects of more frequent and extreme storms were excluded. Climate change was estimated to have been responsible for 3% of diarrhoea, 3% of malaria, and 3.8% of dengue fever deaths worldwide in 2004. Total attributable mortality was about 0.2% of deaths in 2004; of these, 85% were child deaths. The air pollution, wildfires, heat waves caused by the effects of global warming have significantly affected human health.[148]

Projections

A 2014 study by the World Health Organization[149] estimated the effect of climate change on human health. Not all of the effects of climate change were included in their estimates, for example, the effects of more frequent and extreme storms were excluded. The report further assumed continued progress in health and growth. Even so, climate change was projected to cause an additional 250 000 additional deaths per year between 2030 and 2050.[150]

With high confidence, authors of the IPCC AR4 Synthesis report[151]: 48 projected that climate change would bring some benefits in temperate areas, such as fewer deaths from cold exposure, and some mixed effects such as changes in range and transmission potential of malaria in Africa. Benefits were projected to be outweighed by negative health effects of rising temperatures, especially in developing countries.

With very high confidence, Confalonieri et al. (2007)[146]: 393 concluded that economic development was an important component of possible adaptation to climate change. Economic growth on its own, however, was not judged to be sufficient to insulate the world's population from disease and injury due to climate change. Future vulnerability to climate change will depend not only on the extent of social and economic change, but also on how the benefits and costs of change are distributed in society.[152] For example, in the 19th century, rapid urbanization in western Europe lead to a plummeting in population health.[152] Other factors important in determining the health of populations include education, the availability of health services, and public-health infrastructure.[146]: 393

On mental health

In 2018, the American Psychological Association issued a report about the impact of climate change on mental health. It said that "gradual, long-term changes in climate can also surface a number of different emotions, including fear, anger, feelings of powerlessness, or exhaustion".[153] Generally this seems to have the greatest impact on young people. California social scientist, Renee Lertzman, likens the climate-related stress now affecting teenagers and those in their 20s to Cold War fears that gripped young baby boomers who came of age under the threat of nuclear annihilation.[154]

Migration

Gradual but pervasive environmental change and sudden natural disasters both influence the nature and extent of human migration but in different ways.

Slow onset

Slow-onset disasters and gradual environmental erosion such as desertification, reduction of soil fertility, coastal erosion and sea-level rise are likely to induce long term migration.[155] Migration related to desertification and reduced soil fertility is likely to be predominantly from rural areas in developing countries to towns and cities.[156]

Displacement and migration related to sea level rise will mostly affect those who live in cities near the coast. More than 90 US coastal cities are already experiencing chronic flooding and that number is expected to double by 2030.[157] Numerous cities in European will be affected by rising sea levels, especially in the Netherlands, Spain and Italy.[158] Coastal cities in Africa are also under threat due to rapid urbanization and the growth of informal settlements along the coast. [159] According to the World Economic Forum: "The coming decades will be marked by the rise of ex-cities and climate migrants."[160]

Low lying Pacific island nations including Fiji, Kiribati, Nauru, Micronesia, the Marshall Islands, the Solomon Islands, Vanuatu, Timor Leste and Tonga are especially vulnerable to rising seas. In July 2019, they issued a declaration "affirming that climate change poses the single greatest threat to the human rights and security of present and future generations of Pacific Island peoples"[161] and claim their lands could become uninhabitable as early as 2030.[162]

The United Nations says there are already 64 million human migrants in the world fleeing wars, hunger, persecution and the effects of global warming.[163] In 2018, the World Bank estimated that climate change will cause internal migration of between 31 and 143 million people as they escape crop failures, water scarcity, and sea level rise. The study only included Sub-Saharan Africa, South Asia, and Latin America.[164][165] The UN forecasts that by 2050 there could be 200 million environmental migrants.[166][167][failed verification]

Sudden onset

Sudden-onset natural disasters tend to create mass displacement, which may only be short term. However, Hurricane Katrina demonstrated that displacement can last a long time. Estimates suggest that a quarter of the one million people[168] displaced in the Gulf Coast region by Hurricane Katrina had not returned to their homes five years after the disaster.[169] Mizutori, the U.N. secretary-general’s special representative on disaster risk reduction, says millions of people are also displaced from their homes every year as result of sudden-onset disasters such as intense heatwaves, storms and flooding. She says 'climate crisis disasters' are happening at the rate of one a week.[170]

Conflict

A 2013 study found that significant climatic changes were associated with a higher risk of conflict worldwide, and predicted that "amplified rates of human conflict could represent a large and critical social impact of anthropogenic climate change in both low- and high-income countries."[171] Similarly, a 2014 study found that higher temperatures were associated with a greater likelihood of violent crime, and predicted that global warming would cause millions of such crimes in the United States alone during the 21st century.[172]

However, a 2018 study in the journal Nature Climate Change found that previous studies on the relationship between climate change and conflict suffered from sampling bias and other methodological problems.[173] Factors other than climate change may be more important in affecting conflict. For example, Wilbanks et al. (2007)[174] suggested that major environmentally influenced conflicts in Africa were more to do with the relative abundance of resources, e.g., oil and diamonds, than with resource scarcity.

Despite these issues, military planners are concerned that global warming is a "threat multiplier". "Whether it is poverty, food and water scarcity, diseases, economic instability, or threat of natural disasters, the broad range of changing climatic conditions may be far reaching. These challenges may threaten stability in much of the world".[175] For example, the onset of Arab Spring in December 2010 is partly the result of a spike in wheat prices following crop losses from the 2010 Russian heat wave.[176][177]

Economic impact

Aggregating impacts adds up the total impact of climate change across sectors and/or regions.[178] Examples of aggregate measures include economic cost (e.g., changes in gross domestic product (GDP) and the social cost of carbon), changes in ecosystems (e.g., changes over land area from one type of vegetation to another),[179] human health impacts, and the number of people affected by climate change.[180] Aggregate measures such as economic cost require researchers to make value judgements over the importance of impacts occurring in different regions and at different times.

In 2019 global warming contributed to at least 15 sudden onset events that cost more than $1bn each in damage, with more than half of those costing more than $10bn each.[181]

Observed impacts

Global losses reveal rapidly rising costs due to extreme weather-related events since the 1970s.[182] Socio-economic factors have contributed to the observed trend of global losses, e.g., population growth, increased wealth.[183] Part of the growth is also related to regional climatic factors, e.g., changes in precipitation and flooding events. It is difficult to quantify the relative impact of socio-economic factors and climate change on the observed trend.[183] The trend does, however, suggest increasing vulnerability of social systems to climate change.[183][184]

Projected impacts

The total economic impacts from climate change are difficult to estimate. With medium confidence, Smith et al. (2001)[185] concluded that world GDP would change by plus or minus a few percent for a small increase in global mean temperature (up to around 2 °C relative to the 1990 temperature level). Most studies assessed by Smith et al. (2001)[185] projected losses in world GDP for a medium increase in global mean temperature (above 2–3 °C relative to the 1990 temperature level), with increasing losses for greater temperature increases. This assessment is consistent with the findings of more recent studies, as reviewed by Hitz and Smith (2004).[186]

Economic impacts are expected to vary regionally. For a medium increase in global mean temperature (2–3 °C of warming, relative to the average temperature between 1990–2000), market sectors in low-latitude and less-developed areas might experience net costs due to climate change.[22] On the other hand, market sectors in high-latitude and developed regions might experience net benefits for this level of warming.[citation needed] A global mean temperature increase above about 2–3 °C (relative to 1990–2000) would very likely result in market sectors across all regions experiencing either declines in net benefits or rises in net costs.[46]

In 2019 the National Bureau of Economic Research found that increase in average global temperature by 0.04 °C per year, in absence of mitigation policies, will reduce world real GDP per capita by 7.22% by 2100. Following the Paris Agreement, thereby limiting the temperature increase to 0.01 °C per year, reduces the loss to 1.07%.[187]

Sense of crisis

In response to the threat posed by global warming, in May 2018 Roger Hallam and Gail Bradbrook started the civil disobedience movement, Extinction Rebellion, to try and compel government action to address the problem. In August 2018, Greta Thunberg began demonstrating outside the Swedish parliament to bring attention to the issue, calling it an 'existential crisis',[188] galvanising a world-wide movement, especially among young people, towards the need for immediate action.[189][190] To highlight concerns about global warming, in 2019 some media outlets began using the term climate crisis instead of climate change.[191]

In November 2019, over 11,000 climate scientists added their names to a declaration[192] published in the journal BioScience,[193] calling climate warming a “climate emergency.” [194] A few countries[195] and hundreds of cities, councils and local jurisdictions[196] have also declared a climate emergency. Joseph Stiglitz, Nobel laureate in economics, says: “The climate emergency is our third world war. Our lives and civilization as we know it are at stake, just as they were in the Second World War.” [197] The net effect of these changes is even seen by some commentators as an existential threat to civilisation.[198][199][200]

Biological systems

Recent warming has strongly affected natural biological systems.[43] For example, in the Northern Hemisphere, species are almost uniformly moving their ranges northward and up in elevation in search of cooler temperatures.[202] Humans are very likely causing changes in regional temperatures to which plants and animals are responding.[202]

By the year 2100, ecosystems will be exposed to atmospheric CO

2 levels substantially higher than in the past 650,000 years, and global temperatures at least among the highest of those experienced in the past 740,000 years.[203] Significant disruptions of ecosystems are projected to increase with future climate change.[204] Examples of disruptions include disturbances such as fire, drought, pest infestation, invasion of species, storms, and coral bleaching events. The stresses caused by climate change, added to other stresses on ecological systems (e.g., land conversion, land degradation, harvesting, and pollution), threaten substantial damage to or complete loss of some unique ecosystems, and extinction of some critically endangered species.[204][205]

Of the drivers with the biggest global impact on nature, climate change came third over the last five decades, with change in land use and sea use, and direct exploitation of organisms having a larger impact.[206]

Terrestrial and wetland systems

Climate change has been estimated to be a major driver of biodiversity loss in cool conifer forests, savannas, mediterranean-climate systems, tropical forests, in the Arctic tundra.[207] In other ecosystems, land-use change may be a stronger driver of biodiversity loss at least in the near-term.[207] Beyond the year 2050, climate change may be the major driver for biodiversity loss globally.[207]

A literature assessment by Fischlin et al. (2007)[203] included a quantitative estimate of the number of species at increased risk of extinction due to climate change. With medium confidence, it was projected that approximately 20 to 30% of plant and animal species assessed so far (in an unbiased sample) would likely be at increasingly high risk of extinction should global mean temperatures exceed a warming of 2 to 3 °C above pre-industrial temperature levels.[203] The uncertainties in this estimate, however, are large: for a rise of about 2 °C the percentage may be as low as 10%, or for about 3 °C, as high as 40%, and depending on biota (all living organisms of an area, the flora and fauna considered as a unit)[208] the range is between 1% and 80%.[207] As global average temperature exceeds 4 °C above pre-industrial levels, model projections suggested that there could be significant extinctions (40–70% of species that were assessed) around the globe.[207]

Assessing whether future changes in ecosystems will be beneficial or detrimental is largely based on how ecosystems are valued by human society.[209] For increases in global average temperature exceeding 1.5 to 2.5 °C (relative to global temperatures over the years 1980–1999)[210] and in concomitant atmospheric CO

2 concentrations, projected changes in ecosystems will have predominantly negative consequences for biodiversity and ecosystems goods and services, e.g., water and food supply.[211]

Ocean ecosystems

Warm water coral reefs are very sensitive to global warming and ocean acidification. Coral reefs provide a habitat for thousands of species and ecosystem services such as coastal protection and food. The resilience of reefs can be improved by curbing local pollution and overfishing: but most warm water coral reefs will disappear even if warming is kept to 1.5 °C.[212] Coral reefs are not the only framework organisms, organisms that build physical structures that form habitats for other sea creatures affected by climate change: mangroves and seagrass were considered to be at moderate risk for lower levels of global warming according to a literature assessment in the Special Report on the Ocean and Cryosphere in a Changing Climate.[213]

Abrupt or irreversible changes

Self-reinforcing feedbacks amplify and accelerate climate change.[214] The climate system exhibits threshold behaviour or tipping points when these feedbacks lead parts of the Earth system into a new state.[215] Tipping points are studied using data from Earth's distant past and by physical modelling.[215] There is already moderate risk of global tipping points at 1 °C above pre-industrial temperatures, and that risk becomes high at 2.5 °C.[216]

Tipping points are "perhaps the most ‘dangerous’ aspect of future climate changes", leading to irreversible impacts on society.[217] Many tipping points are interlinked, so that triggering one can possible lead to a cascade of effects.[218] A 2018 study states that 45% of the environmental problems, including those caused by climate change are interconnected and make the risk of a "domino effect" bigger.[219][220]

Amazon rain forest

Rainfall that falls on the Amazon rainforest is recycled when it evaporates back into the atmosphere instead of running off away from the rainforest. This water is essential for sustaining the rainforest. Due to deforestation the rainforest is losing this ability, exacerbated by climate change which brings more frequent droughts to the area. The higher frequency of droughts seen in the first two decades of the 21st century signal that a tipping point from rainforest to savanna might be close.[221]

Greenland and West Antarctic Ice sheets

Future melt of the West Antarctic ice sheet is potentially abrupt under a high emission scenario, as a consequence of a partial collapse.[222] Part of the ice sheet is grounded on bedrock below sea level, making it possibly vulnerable to the self-enhancing process of marine ice sheet instability. A further hypothesis is that marine ice cliff instability would also contribute to a partial collapse, but limited evidence is available for its importance.[223] A partial collapse of the ice sheet would lead to rapid sea level rise and a local decrease in ocean salinity. It would be irreversible on a timescale between decades and millennia.[222]

In contrast to the West Antarctic ice sheet, melt of the Greenland ice sheet is projected to be taking place more gradually over millennia.[222] Sustained warming between 1 °C (low confidence) and 4 °C (medium confidence) would lead to a complete loss of the ice sheet, contributing 7 m to sea levels globally.[224] The ice loss could become irreversible due to a further self-enhancing feedback: the elevation-surface mass balance feedback. When ice melts on top of the ice sheet, the elevation drops. As air temperature is higher at lower altitude, this promotes further melt.[225]

Atlantic Meridional Overturning Circulation

The Atlantic Meridional Overturning Circulation (AMOC). an important component of the Earth's climate system, is a northward flow of warm, salty water in the upper layers of the Atlantic and a southward flow of colder water in the deep Atlantic.[227]: 5 Potential impacts associated with AMOC changes include reduced warming or (in the case of abrupt change) absolute cooling of northern high-latitude areas near Greenland and north-western Europe, an increased warming of Southern Hemisphere high-latitudes, tropical drying, as well as changes to marine ecosystems, terrestrial vegetation, oceanic CO

2 uptake, oceanic oxygen concentrations, and shifts in fisheries.[228]

According to a 2019 assessment in the IPCC's Special Report on the Ocean and Cryosphere in a Changing Climate it is very likely (greater than 90% probability, based on expert judgement) that the strength of the AMOC will decrease further over the course of the 21st century.[229] Warming is still expected to occur over most of the European region downstream of the North Atlantic Current in response to increasing GHGs, as well as over North America. With medium confidence, the IPCC stated that it is very unlikely (less than 10% probability) that the AMOC will collapse in the 21st century,[229] The potential consequences of such a collapse could be severe.[227]: 5

Irreversibilities

Commitment to radiative forcing

Emissions of GHGs are a potentially irreversible commitment to sustained radiative forcing in the future.[230] The contribution of a GHG to radiative forcing depends on the gas's ability to trap infrared (heat) radiation, the concentration of the gas in the atmosphere, and the length of time the gas resides in the atmosphere.[230]

CO

2 is the most important anthropogenic GHG.[231] While more than half of the CO

2 emitted is currently removed from the atmosphere within a century, some fraction (about 20%) of emitted CO

2 remains in the atmosphere for many thousands of years.[232] Consequently, CO

2 emitted today is potentially an irreversible commitment to sustained radiative forcing over thousands of years.

This commitment may not be truly irreversible should techniques be developed to remove CO

2 or other GHGs directly from the atmosphere, or to block sunlight to induce cooling.[33] Techniques of this sort are referred to as geoengineering. Little is known about the effectiveness, costs or potential side-effects of geoengineering options.[233] Some geoengineering options, such as blocking sunlight, would not prevent further ocean acidification.[233]

Irreversible impacts

Human-induced climate change may lead to irreversible impacts on physical, biological, and social systems.[234] There are a number of examples of climate change impacts that may be irreversible, at least over the timescale of many human generations.[235] These include the large-scale singularities such as the melting of the Greenland and West Antarctic ice sheets, and changes to the AMOC.[235] In biological systems, the extinction of species would be an irreversible impact.[235] In social systems, unique cultures may be lost due to climate change.[235] For example, humans living on atoll islands face risks due to sea level rise, sea surface warming, and increased frequency and intensity of extreme weather events.[236]

See also

- Anthropocene

- Risks to civilization, humans and planet Earth

- Indigenous Peoples Climate Change Assessment Initiative

- Environmental sociology

- Regional effects of global warming

Citations

- ^ NOAA 2010, p. 2

- ^ a b Cramer, W., et al., Executive summary, in: Chapter 18: Detection and attribution of observed impacts (archived 18 October 2014), pp.982–984, in IPCC AR5 WG2 A 2014

- ^ Settele, J., et al., Section 4.3.2.1: Phenology, in: Chapter 4: Terrestrial and inland water systems (archived 20 October 2014), p.291, in IPCC AR5 WG2 A 2014

- ^

Hegerl, G.C.; et al. "Ch 9: Understanding and Attributing Climate Change". Executive Summary.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help), in IPCC AR4 WG1 2007 - ^ IPCC (2018). "Summary for Policymakers" (PDF). IPCC SR15 2018. p. 5.

- ^ a b Siegmund, Peter; Abermann, Jakob; Baddour, Omar; Canadell, Pep (2019). The Global Climate in 2015–2019. World Meteorological Society. p. 3.

- ^ a b Oppenheimer, M., et al., Section 19.7.1: Relationship between Adaptation Efforts, Mitigation Efforts, and Residual Impacts, in: Chapter 19: Emergent risks and key vulnerabilities (archived 20 October 2014), pp.1080–1085, in IPCC AR5 WG2 A 2014

- ^ Oppenheimer, M., et al., Section 19.6.2.2. The Role of Adaptation and Alternative Development Pathways, in: Chapter 19: Emergent risks and key vulnerabilities (archived 20 October 2014), pp.1072–1073, in IPCC AR5 WG2 A 2014

- ^ Climate Change Is Already Driving Mass Migration Around the Globe, Natural Resources Defense Council, 25 January 2019

- ^ Environmental Migrants: Up To 1 Billion By 2050

- ^ Field, C.B., et al., Section A-3. The Decision-making Context, in: Technical summary (archived 18 October 2014), p.55, in IPCC AR5 WG2 A 2014

- ^ SPM.4.1 Long‐term mitigation pathways, in: IPCC (2014). "Summary for Policymakers" (PDF). IPCC AR5 WG3 2014. p. 12.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|display-authors=4(help) - ^ Clarke, L., et al., Section 6.3.1.3 Baseline emissions projections from fossil fuels and industry (pp.17–18 of final draft), in: Chapter 6: Assessing Transformation Pathways (archived 20 October 2014), in: IPCC AR5 WG3 2014

- ^ Greenhouse Gas Concentrations and Climate Implications, p.14, in Prinn & Reilly 2014. The range given by Prinn and Reilly is 3.3 to 5.5 °C, with a median of 3.9 °C.

- ^ SPM.3 Trends in stocks and flows of greenhouse gases and their drivers, in: Summary for Policymakers, p.8 (archived 2 July 2014), in IPCC AR5 WG3 2014. The range given by the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change is 3.7 to 4.8 °C, relative to pre-industrial levels (2.5 to 7.8 °C including climate uncertainty).

- ^ Field, C.B., et al., Box TS.8: Adaptation Limits and Transformation, in: Technical summary (archived 18 October 2014), p.89, in IPCC AR5 WG2 A 2014

- ^ Field, C.B., et al., Section B-1. Key Risks across Sectors and Regions, in: Technical summary (archived 18 October 2014), p.62, in IPCC AR5 WG2 A 2014

- ^ Kennedy, John; Ramasamy, Selvaraju; Andrew, Robbie; Arico, Salvatore; Bishop, Erin; Braathen, Geir (2019). WMO statement on the State of the Global Climate in 2018. Geneva: Chairperson, Publications Board, World Meteorological Organization. p. 6. ISBN 978-92-63-11233-0.

- ^ Even 50-year-old climate models correctly predicted global warming, Science, American Association for the Advancement of Science, 4 December 2019

- ^ Neukom, Raphael; Steiger, Nathan; Gómez-Navarro, Juan José; Wang, Jianghao; Werner, Johannes P. (2019). "No evidence for globally coherent warm and cold periods over the preindustrial Common Era". Nature. 571 (7766): 550–554. doi:10.1038/s41586-019-1401-2. ISSN 1476-4687.

- ^ Dunne, Daisy (2019-07-24). "Global extent of climate change is 'unparalleled' in past 2,000 years". Carbon Brief. Retrieved 2019-11-24.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: url-status (link) - ^ a b Schneider; et al., "Chapter 19: Assessing key vulnerabilities and the risk from climate change", Contribution of Working Group II to the Fourth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change, 2007, Sec. 19.3.1 Introduction to Table 19.1, in IPCC AR4 WG2 2007.

- ^ IPCC (2013). "Summary for Policymakers" (PDF). IPCC AR5 WG1 2013.

- ^ IPCC, "Summary for Policymakers", Human and Natural Drivers of Climate Change, Human and Natural Drivers of Climate Change, in IPCC AR4 WG1 2007.

- ^ Explainer: How ‘Shared Socioeconomic Pathways’ explore future climate change, Carbon Brief, 19 April 2018

- ^ The Shared Socioeconomic Pathways and their energy, land use, and greenhouse gas emissions implications: An overview, Global Environmental Change, Volume 42, January 2017, Pages 153-168

- ^ a b c d

Karl 2009 (ed.). "Global Climate Change" (PDF). Global Climate Change Impacts in the United States. pp. 22–24.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: numeric names: editors list (link) - ^ a b United Nations Environment Programme (UNEP) (November 2010), "Ch 2: Which emissions pathways are consistent with a 2 °C or a 1.5 °C temperature limit?: Sec 2.2 What determines long-term temperature?" (PDF), The Emissions Gap Report: Are the Copenhagen Accord pledges sufficient to limit global warming to 2 °C or 1.5 °C? A preliminary assessment (advance copy), UNEP, archived from the original (PDF) on 2011-05-27, p.28. This publication is also available in e-book format Archived 2010-11-25 at the Library of Congress Web Archives

- ^ "Box 8.1 Likelihood of exceeding a temperature increase at equilibrium, in: Ch 8: The Challenge of Stabilisation" (PDF), In Stern 2006, p. 195

- ^ RCP 8.5: Business-as-usual or a worst-case scenario, Climate Nexus, retrieved from https://climatenexus.org/climate-change-news/rcp-8-5-business-as-usual-or-a-worst-case-scenario/

- ^ IPCC, 2013: Summary for Policymakers. In: Climate Change 2013: The Physical Science Basis. Contribution of Working Group I to the Fifth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change p.20

- ^ Temperatures, Climate Action Tracker

- ^ a b Solomon, S.; et al. (January 28, 2009). "Irreversible climate change due to carbon dioxide emissions". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 106 (6). US National Academy of Sciences: 1704–9. Bibcode:2009PNAS..106.1704S. doi:10.1073/pnas.0812721106. PMC 2632717. PMID 19179281.

- ^ Meehl, G.A.; et al., "Ch 10: Global Climate Projections", In IPCC AR4 WG1 2007, Sec 10.7.2 Climate Change Commitment to Year 3000 and Beyond to Equilibrium

- ^ Joyce, Christopher (30 August 2018). "To Predict Effects Of Global Warming, Scientists Looked Back 20,000 Years". NPR.org. Retrieved 2019-12-29.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: url-status (link) - ^ a b Overpeck, J.T. (20 August 2008), NOAA Paleoclimatology Global Warming – The Story: Proxy Data, NOAA Paleoclimatology Program – NCDC Paleoclimatology Branch

- ^ The 20th century was the hottest in nearly 2,000 years, studies show, 25 July 2019

- ^ a b

Jansen; et al., "Chapter 6: Palaeoclimate", Sec. 6.3.2 What Does the Record of the Mid-Pliocene Show?

{{citation}}: Missing or empty|title=(help), in IPCC AR4 WG1 2007. - ^ Hansen, J.E.; M. Sato (July 2011), NASA GISS: Science Briefs: Earth's Climate History: Implications for Tomorrow, New York City, New York: NASA GISS

- ^

Smith, J.B.; et al., "Ch 19. Vulnerability to Climate Change and Reasons for Concern: A Synthesis", Footnote 4, in Sec 19.8.2. What does Each Reason for Concern Indicate?

{{citation}}: Missing or empty|title=(help), in IPCC TAR WG2 2001, p. 957 - ^ NOAA 2010, p. 3

- ^ Solomon; et al., "Technical Summary", Consistency Among Observations, TS.3.4 Consistency Among Observations, in IPCC AR4 WG1 2007.

- ^ a b Rosenzweig; et al., "Chapter 1: Assessment of Observed Changes and Responses in Natural and Managed Systems", IPCC AR4 WG2 2007, Executive summary

- ^

IPCC, "Summary for Policymakers", Sec. 3. Projected climate change and its impacts

{{citation}}: Check|chapter-url=value (help); Missing or empty|title=(help), in IPCC AR4 SYR 2007. - ^ ESRL web team (26 January 2009). "ESRL News: New Study Shows Climate Change Largely Irreversible" (Press release). US Department of Commerce, NOAA, Earth System Research Laboratory (ESRL).

- ^ a b c

IPCC, "Summary for Policymakers", Magnitudes of impact

{{citation}}: Missing or empty|title=(help), p.17, IPCC AR4 WG2 2007. - ^

Executive Summary (PHP). United States National Academy of Sciences. June 2002.

{{cite book}}:|work=ignored (help)[full citation needed] - ^ The science connecting extreme weather to climate change, Fact sheet: Union of Concerned Scientists, June 2018.

- ^ Effects of Global Warming, Live Science, 12 August 2017

- ^ Early Warning Signs of Global Warming: Downpours, Heavy Snowfalls, and Flooding, Union of Concerned Scientists, 10 November 2003

- ^ NOAA Geophysical Fluid Dynamics Laboratory (GFDL) (9 October 2012), GFDL Climate Modeling Research Highlights: Will the Wet Get Wetter and the Dry Drier, NOAA GFDL

- ^ a b c d NOAA (February 2007), "Will the wet get wetter and the dry drier?" (PDF), GFDL Climate Modeling Research Highlights, vol. 1, no. 5, Princeton, NJ: National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) Geophysical Fluid Dynamics Laboratory (GFDL). Revision 10/15/2008, 4:47:16 PM.

- ^ Global warming is increasing rainfall rates, The Guardian, 22 March 2017

- ^ Atmospheric River Change, Climate Signals, 4 December 2018

- ^ "Summary for policymakers", In IPCC SREX 2012, p. 8

- ^ Explainer: What climate models tell us about future rainfall, Carbon Brief 19 January 2018

- ^ a b c d e f g IPCC (2013), Table SPM.1, in Summary for Policymakers, p. 5 (archived PDF), in IPCC AR5 WG1 2013

- ^ Press, Associated (2019-03-19). "Record high US temperatures outpace record lows two to one, study finds". the Guardian. Retrieved 2019-03-19.

- ^ Freedman, Andrew (2019-03-19). "The ratio of warm and cold temperature records is increasingly skewed - Axios". Axios. Retrieved 2019-03-19.

- ^ Stocker, T.F., et al. (2013), Temperature Extremes, Heat Waves and Warm Spells, in: TFE.9, in: Technical Summary, p. 111 (archived PDF), in IPCC AR5 WG1 2013

- ^ Stocker, T.F., et al. (2013), Floods and Droughts, in: TFE.9, in: Technical Summary, p. 112 (archived PDF), in IPCC AR5 WG1 2013

- ^ Global Warming Makes Heat Waves More Likely, Study Finds 10 July 2012 NYT

- ^ Hansen, J; Sato, M; Ruedy, R (2012). "Perception of climate change". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 109 (37): E2415–23. doi:10.1073/pnas.1205276109. PMC 3443154. PMID 22869707.

- ^ Heat wave: meteorology. Encyclopedia Britannica. Retrieved 1 April 2019.

- ^ "Heat Waves: The Details". Climate Communication. Retrieved 16 August 2018.

- ^ a b Christensen, J.H.,et al. (2013), Cyclones, in: Executive Summary, in: Chapter 14: Climate Phenomena and their Relevance for Future Regional Climate Change, p. 1220 (archived PDF), in IPCC AR5 WG1 2013

- ^ Collins, M.; Sutherland, M.; Bouwer, L.; Cheong, S. M.; et al. (2019). "Chapter 6: Extremes, Abrupt Changes and Managing Risks" (PDF). IPCC SROCC 2019. p. 592.

- ^ The peak structure and future changes of the relationships between extreme precipitation and temperature, Nature Climate Change volume 7, pp 268–274 (2017)

- ^ Global warming is increasing rainfall rates, The Guardian, 22 March 2017

- ^ Climate change: Sea level rise to affect 'three times more people', BBC News, 30 October 2019

- ^ Rising sea levels pose threat to homes of 300m people – study, The Guardian, 29 October 2019

- ^ New elevation data triple estimates of global vulnerability to sea-level rise and coastal flooding, Nature Communications, Vol 10, Article number: 4844 (2019)

- ^ Is Global Warming Fueling Increased Wildfire Risks? Union of Concerned Scientists, 24 July 2018

- ^ climate change is contributing to California’s fires, National Geographic

- ^ As Smoke From Bushfires Chokes Sydney, Australian Prime Minister Dodges on Climate Change, Time 21 November 2019.

- ^ The facts about bushfires and climate change, Climate Council, 13 November 2019

- ^ What is the cryosphere? National ocean Service

- ^ Getting to Know the Cryosphere, Earth Labs

- ^ Impacts of a melting cryosphere ice loss around the world, Carbon Brief, 9 June 2011

- ^ 2011 Arctic Sea Ice Minimum, archived from the original on 2013-06-14, retrieved 2013-03-20, in Kennedy 2012

- ^ Kwok, R. (2018-10-12). "Arctic sea ice thickness, volume, and multiyear ice coverage: losses and coupled variability (1958–2018)". Environmental Research Letters. 13 (10): 105005. doi:10.1088/1748-9326/aae3ec. ISSN 1748-9326.

- ^ IPCC (2018). "Summary for Policymakers" (PDF). IPCC SR15 2018. p. 8.

- ^ Mass Balance of Mountain Glaciers in 2011, archived from the original on 2013-06-14, retrieved 2013-03-20, in Kennedy 2012

- ^ 2011 Snow Cover in Northern Hemisphere, archived from the original on 2013-06-13, retrieved 2013-03-20, in Kennedy 2012

- ^

Meehl, G.A.; et al., "Ch 10: Global Climate Projections", Box 10.1: Future Abrupt Climate Change, ‘Climate Surprises’, and Irreversible Changes: Glaciers and ice caps

{{citation}}: Missing or empty|title=(help), in IPCC AR4 WG1 2007, p. 776 - ^

Meehl, G.A.; et al., "Ch 10: Global Climate Projections", Sec 10.3.3.2 Changes in Snow Cover and Frozen Ground

{{citation}}: Missing or empty|title=(help), in IPCC AR4 WG1 2007, pp. 770, 772 - ^

Field, C.B.; et al., "Ch 14: North America", Sec 14.4.1 Freshwater resources: Surface water

{{citation}}: Missing or empty|title=(help), in IPCC AR4 WG2 2007, p. 627 - ^

Some of these impacts are included in table SPM.2: "Summary for Policymakers", 3 Projected climate change and its impacts: Table SPM.2

{{citation}}: Missing or empty|title=(help), in IPCC AR4 SYR 2007, pp. 11–12 - ^

"Ch 3: Fresh Water Resources and their Management", Sec 3.4.3 Floods and droughts

{{citation}}: Missing or empty|title=(help), in IPCC AR4 WG2 2007, p. 187 - ^ Barnett, T.P.; et al. (17 November 2005), "Potential impacts of a warming climate on water availability in snow-dominated regions: Abstract" (PDF), Nature, 438 (7066): 303–9, Bibcode:2005Natur.438..303B, doi:10.1038/nature04141, PMID 16292301, archived from the original (PDF) on 1 October 2018, retrieved 20 March 2013

- ^ a b Bindoff, N. L.; Cheung, W. W. L.; Kairo, J. G.; Arístegui, J.; et al. (2019). "Chapter 5: Changing Ocean, Marine Ecosystems, and Dependent Communities" (PDF). IPCC SROCC 2019. p. 471.

- ^ Bindoff, N.L.; et al., "Ch. 5: Observations: Oceanic Climate Change and Sea Level", Sec 5.2.2.3 Implications for Earth’s Heat Balance

{{citation}}: Missing or empty|title=(help), in IPCC AR4 WG1 2007, referred to by: Climate Graphics by Skeptical Science: Global Warming Components, Skeptical Science, Components of global warming for the period 1993 to 2003 calculated from IPCC AR4 5.2.2.3 - ^ Cheng, Lijing; Abraham, John; Hausfather, Zeke; E. Trenberth, Kevin (11 January 2019). "How fast are the oceans warming?". Science. 363 (6423). Retrieved 11 January 2019.

- ^ SHOOT, BRITTANY (11 January 2019). "New Climate Change Report Says Ocean Warming Is Far Worse Than Expected". Fortune. Retrieved 11 January 2019.

- ^ State of the Climate in 2009, as appearing in the July 2010 issue (Vol. 91) of the Bulletin of the American Meteorological Society (BAMS). Supplemental and Summary Materials: Report at a Glance: Highlights. Website of the US National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration: National Climatic Data Center. July 2010. Retrieved 2011-06-06.

- ^ Crowley, T. J.; North, G. R. (May 1988). "Abrupt Climate Change and Extinction Events in Earth History". Science. 240 (4855): 996–1002. Bibcode:1988Sci...240..996C. doi:10.1126/science.240.4855.996. PMID 17731712.

- ^ Shaffer, G. .; Olsen, S. M.; Pedersen, J. O. P. (2009). "Long-term ocean oxygen depletion in response to carbon dioxide emissions from fossil fuels". Nature Geoscience. 2 (2): 105–109. Bibcode:2009NatGe...2..105S. doi:10.1038/ngeo420.

- ^ Bindoff, N. L.; Cheung, W. W. L.; Kairo, J. G.; Arístegui, J.; et al. (2019). "Chapter 5: Changing Ocean, Marine Ecosystems, and Dependent Communities" (PDF). IPCC SROCC 2019. p. 457.

- ^ Bindoff, N. L.; Cheung, W. W. L.; Kairo, J. G.; Arístegui, J.; et al. (2019). "Chapter 5: Changing Ocean, Marine Ecosystems, and Dependent Communities" (PDF). IPCC SROCC 2019. p. 463.

- ^ Riebesell, Ulf; Körtzinger, Arne; Oschlies, Andreas (2009). "Sensitivities of marine carbon fluxes to ocean change". PNAS. 106 (49).

- ^ Bindoff, N. L.; Cheung, W. W. L.; Kairo, J. G.; Arístegui, J.; Guinder, V. A.; et al. (2019). "Chapter 5: Changing Ocean, Marine Ecosystems, and Dependent Communities" (PDF). IPCC SROCC 2019. p. 450.

- ^ US Environmental Protection Agency (US EPA) (2010). "Sea Level: Climate Change: US EPA". US EPA.

- ^ IPCC (2019). "Summary for Policymakers" (PDF). IPCC SROCC 2019.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|display-authors=4(help) - ^ IPCC AR% Summary for Policy Makers

- ^ The Oceans We Know Won’t Survive Climate Change, The Atlantic, 25 September 2019

- ^ Glavovic, B.; Oppenheimer, M.; Abd-Elgawad, A.; Cai, R.; et al. (2019). "Chapter 4: Sea Level Rise and Implications for Low Lying Islands, Coasts and Communities" (PDF). IPCC SROCC 2019. p. 4-3.

- ^ Glavovic, B.; Oppenheimer, M.; Abd-Elgawad, A.; Cai, R.; et al. (2019). "Chapter 4: Sea Level Rise and Implications for Low Lying Islands, Coasts and Communities" (PDF). IPCC SROCC 2019. p. 4-9.

- ^

Meehl; et al., "Chapter 10: Global Climate Projections", Executive summary

{{citation}}: Missing or empty|title=(help), in IPCC AR4 WG1 2007. - ^ Chapter 4: Sea Level Rise and Implications for Low Lying Islands, Coasts and Communities, IPCC SR Ocean and Cryosphere, p.3.

- ^ Mengel, Matthias; Nauels, Alexander; Rogelj, Joeri; Schleussner, Carl-Friedrich (2018-02-20). "Committed sea-level rise under the Paris Agreement and the legacy of delayed mitigation action". Nature Communications. 9 (1): 1–10. doi:10.1038/s41467-018-02985-8. ISSN 2041-1723.

- ^ Simulation shows ‘unavoidable’ 3m Auckland sea level rise. TVNZ 25 July 2015.

- ^ Sea levels could rise by more than three metres, shows new study, PhysOrg, 26 April 2017

- ^ Amos, Jonathan (2019-10-30). "Sea level rise to affect 'three times more people'". Retrieved 2019-11-26.

- ^ US Environmental Protection Agency (14 June 2012). "Science: Climate Change: US EPA (Climate Change Science Overview)". US EPA.

- ^ Herring, D. (March 6, 2012). "ClimateWatch Magazine » Global Temperature Projections". NOAA Climate Portal. Archived from the original on June 14, 2013. Retrieved July 24, 2012.

- ^ a b IPCC, "Synthesis report", Sec. 3.3.3 Especially affected systems, sectors and regions

{{citation}}: Missing or empty|title=(help), in IPCC AR4 SYR 2007. - ^ a b Schneider, S.H.; et al., "Ch 19: Assessing Key Vulnerabilities and the Risk from Climate Change", Distribution of Impacts, in: Sec 19.3.7 Update on 'Reasons for Concern'

{{citation}}: Missing or empty|title=(help), in IPCC AR4 WG2 2007, p. 796 - ^ a b Schneider, S.H.; et al., "Ch 19: Assessing Key Vulnerabilities and the Risk from Climate Change", Sec 19.3.3 Regional vulnerabilities

{{citation}}: Missing or empty|title=(help), in IPCC AR4 WG2 2007, p. 792 - ^ Wilbanks, T.J.; et al., "Ch 7: Industry, Settlement and Society", Sec 7.4.2.5 Social issues and Sec 7.4.3 Key vulnerabilities

{{citation}}: Missing or empty|title=(help), in IPCC AR4 WG2 2007, pp. 373–376 - ^ US NRC (2008). Understanding and Responding to Climate Change. A brochure prepared by the US National Research Council (US NRC) (PDF). Washington DC: Board on Atmospheric Sciences and Climate, National Academy of Sciences.

{{cite book}}: External link in|publisher= - ^ IPCC, "Summary for Policymakers", Projections of Future Changes in Climate

{{citation}}: Missing or empty|title=(help), in IPCC AR4 WG1 2007. - ^ Hoegh-Guldberg, O.; Jacob, D.; Taylor, M.; Bindi, M.; et al. (2018). "Chapter 3: Impacts of 1.5ºC Global Warming on Natural and Human Systems" (PDF). IPCC SR15 2018. p. 190.

- ^ Director, International (2018-10-15). "The Industries and Countries Most Vulnerable to Climate Change". International Director. Retrieved 2019-12-15.

- ^ Hoegh-Guldberg, O.; Jacob, D.; Taylor, M.; Bindi, M.; et al. (2018). "Chapter 3: Impacts of 1.5ºC Global Warming on Natural and Human Systems" (PDF). IPCC SR15 2018. pp. 212–213, 228, 252.

- ^ "FAOSTAT". faostat3.fao.org.

- ^ Easterling; et al., "Chapter 5: Food, Fibre, and Forest Products", In IPCC AR4 WG2 2007, p. 282

- ^ Mbow, C.; Rosenzweig, C.; Barioni, L. G.; Benton, T.; et al. (2019). "Chapter 5: Food Security" (PDF). IPCC SRCCL 2019. p. 442.

- ^ a b Figure 5.1, p.161, in: Sec 5.1 FOOD PRODUCTION, PRICES, AND HUNGER, in: Ch 5: Impacts in the Next Few Decades and Coming Centuries, in: US NRC 2011

- ^ IPCC (2019). "Summary for Policymakers" (PDF). IPCC SRCCL 2019. p. 8.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|display-authors=4(help) - ^ Mbow, C.; Rosenzweig, C.; Barioni, L. G.; Benton, T.; Herrero, M.; et al. (2019). "Chapter 5: Food Security" (PDF). IPCC SRCCL 2019. p. 453.

- ^ IPCC (2019). "Summary for Policymakers" (PDF). IPCC SROCC 2019. p. 12.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|display-authors=4(help) - ^ Bindoff, N. L.; Cheung, W. W. L.; Kairo, J. G.; Arístegui, J.; Guinder, V. A.; et al. (2019). "Chapter 5: Changing Ocean, Marine Ecosystems, and Dependent Communities" (PDF). IPCC SROCC 2019. p. 504.

- ^ a b c Mbow, C.; Rosenzweig, C.; Barioni, L. G.; Benton, T.; et al. (2019). "Chapter 5: Food Security" (PDF). IPCC SRCCL 2019. p. 439.

- ^ Mbow, C.; Rosenzweig, C.; Barioni, L. G.; Benton, T.; et al. (2019). "Chapter 5: Food Security" (PDF). IPCC SRCCL 2019. p. 439.

- ^ Myers, Samuel S.; Smith, Matthew R.; Guth, Sarah; Golden, Christopher D.; Vaitla, Bapu; Mueller, Nathaniel D.; Dangour, Alan D.; Huybers, Peter (2017-03-20). "Climate Change and Global Food Systems: Potential Impacts on Food Security and Undernutrition". Annual Review of Public Health. 38 (1): 259–277. doi:10.1146/annurev-publhealth-031816-044356. ISSN 0163-7525.

- ^ Dai, A. (2011). "Drought under global warming: A review". Wiley Interdisciplinary Reviews: Climate Change. 2: 45–65. Bibcode:2011AGUFM.H42G..01D. doi:10.1002/wcc.81.

- ^ Sheffield, J.; Wood, E. F.; Roderick, M. L. (2012). "Little change in global drought over the past 60 years". Nature. 491 (7424): 435–438. Bibcode:2012Natur.491..435S. doi:10.1038/nature11575. PMID 23151587.

- ^ Mishra, A. K.; Singh, V. P. (2011). "Drought modeling – A review". Journal of Hydrology. 403 (1–2): 157–175. Bibcode:2011JHyd..403..157M. doi:10.1016/j.jhydrol.2011.03.049.

- ^ Ding, Y.; Hayes, M. J.; Widhalm, M. (2011). "Measuring economic impacts of drought: A review and discussion". Disaster Prevention and Management. 20 (4): 434–446. doi:10.1108/09653561111161752.

- ^ Kundzewicz; et al., "Chapter 3: Fresh Water Resources and their Management", IPCC AR4 WG2 2007, Sec. 3.2 Current sensitivity/vulnerability

- ^ Kundzewicz; et al., "Chapter 3: Fresh Water Resources and their Management", IPCC AR4 WG2 2007, Sec. 3.3 Executive summary

- ^ "Freshwater (Lakes and Rivers) - The Water Cycle". usgs.gov. Retrieved 2019-05-01.

- ^ Jiménez Cisneros, B. E.; Oki, T.; Arnell, N. W.; Benito, G.; et al. (2014). "Chapter 3: Freshwater Resources" (PDF). IPCC AR5 WG2 A 2014. p. 251.

- ^ a b Jiménez Cisneros, B. E.; Oki, T.; Arnell, N. W.; Benito, G.; et al. (2014). "Chapter 3: Freshwater Resources" (PDF). IPCC AR5 WG2 A 2014. p. 232.

- ^ Jiménez Cisneros, B. E.; Oki, T.; Arnell, N. W.; Benito, G.; et al. (2014). "Chapter 3: Freshwater Resources" (PDF). IPCC AR5 WG2 A 2014. p. 247.

- ^ a b c

Confalonieri; et al., "Chapter 8: Human health", Executive summary

{{citation}}: Missing or empty|title=(help), in IPCC AR4 WG2 2007. - ^ WHO (2009). "Ch. 2, Results: 2.6 Environmental risks" (PDF). Global health risks: mortality and burden of disease attributable to selected major risks (PDF). Geneva, Switzerland: WHO Press. p. 24. ISBN 978-92-4-156387-1.

- ^ Takaro, Tim K; Knowlton, Kim; Balmes, John R (August 2013). "Climate change and respiratory health: current evidence and knowledge gaps". Expert Review of Respiratory Medicine. 7 (4): 349–361. doi:10.1586/17476348.2013.814367. ISSN 1747-6348.

- ^ Quantitative risk assessment of the effects of climate change on selected causes of death, 2030s and 2050s. World Health Organization. 2014. ISBN 978-92-4-150769-1.

{{cite book}}: Cite uses deprecated parameter|authors=(help) - ^ COP24 special report: health and climate change. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2018. p.24. Cataloguing-in-Publication (CIP) data. CIP data are available at http://apps.who.int/iris.

- ^ IPCC AR4 SYR 2007.

- ^ a b

Confalonieri; et al., "Chapter 8: Human health", Sec. 8.3.2 Future vulnerability to climate change