Qubba

A qubba (Arabic: قُبَّة, romanized: qubba(t), pl. قُباب qubāb),[3] also transliterated as ḳubba, kubbet and koubba, is a cupola or domed structure, typically a tomb or shrine in Islamic architecture.[1][2][4][5] In many regions, such as North Africa, the term qubba is applied commonly for the tomb of a local wali (local Muslim saint or marabout), and usually consists of a chamber covered by a dome or pyramidal cupola.[6][7][1]

Etymology

[edit]The Arabic word qubba was originally used to mean a tent of hides,[8] or generally the assembly of a material such as cloth into a circle.[3] It's likely that this original meaning was extended to denote domed buildings after the latter had developed in Islamic architecture.[3] It is now also used generally for tomb sites if they are places of pilgrimage.[9] In Turkish and Persian the word kümbet, kumbad, or gunbād has a similar meaning for dome or domed tomb.[3]

Historical development

[edit]

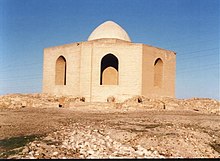

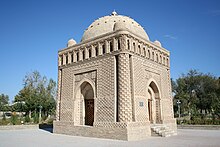

A well-known example of an Islamic domed shrine is the Dome of the Rock, known in Arabic as Qubbat aṣ-Ṣakhra (Arabic: قُبَّةُ ٱلْصَّخْرَة), although this particular monumental example is exceptional in early Islamic architecture.[3] In early Islamic culture, the construction of mausoleums and ostentations tomb structures to commemorate the deceased was viewed as unorthodox. According to many muslims, Muhammad himself opposed such practices. They cite a hadith in support of their claim, in which Muhammad ordered Ali to level the high graves.[2][3] But proponents of elevating graves claim that this directive applies only to infidels and polytheists, not to any Muslim.[10] However, historical records indicate that from the 8th century onward mausoleums became common, propagated in part by their popularity among the Shi'a, who built tombs to commemorate the Imams which in turn became places of religious ceremony and pilgrimage.[2][3] The oldest surviving example of a domed tomb in Islamic architecture is the Qubbat al-Sulaibiyya in Samarra, present-day Iraq, dating from the mid-9th century.[1][2] The construction of domed tombs became more common among both Shi'as and Sunnis during the tenth century, although early Sunni mausoleums were mostly built for political rulers.[3] An example of the latter is the Samanid Mausoleum in Bukhara, present-day Uzbekistan, built in the tenth century.[3]

In Yazidism

[edit]Yazidi shrines and sacred buildings typically have conical spires that are known as qubbe in Kurdish.[11]

See also

[edit]- History of medieval Arabic and Western European domes

- Maqam (shrine), regional term: wali or weli

- Mazar (mausoleum)

- Islamic pilgrimage

- Türbe, Ottoman mausoleums

- Gonbad

References

[edit]Citations

[edit]- ^ a b c d Petersen, Andrew (1996). Dictionary of Islamic architecture. Routledge. p. 240. ISBN 978-1134613663.

- ^ a b c d e M. Bloom, Jonathan; S. Blair, Sheila, eds. (2009). "Tomb". The Grove Encyclopedia of Islamic Art and Architecture. Oxford University Press. p. 342. ISBN 978-0195309911.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i Tabbaa, Yasser (2017). "Dome". In Fleet, Kate; Krämer, Gudrun; Matringe, Denis; Nawas, John; Rowson, Everett (eds.). Encyclopaedia of Islam, Three. Brill. ISBN 978-9004161658.

- ^ Ettinghausen, Richard; Grabar, Oleg; Jenkins-Madina, Marilyn (2001). Islamic Art and Architecture: 650–1250 (2nd ed.). Yale University Press. p. 338. ISBN 978-0300088670.

- ^ Petersen (2001), p. 326.

- ^ Binous, Jamila; Baklouti, Naceur; Ben Tanfous, Aziza; Bouteraa, Kadri; Rammah, Mourad; Zouari, Ali (2010). Ifriqiya: Thirteen Centuries of Art and Architecture in Tunisia. Islamic Art in the Mediterranean. Museum With No Frontiers & Ministry of Culture, the National Institute of Heritage, Tunis.

- ^ Touri, Abdelaziz; Benaboud, Mhammad; Boujibar El-Khatib, Naïma; Lakhdar, Kamal; Mezzine, Mohamed (2010). Andalusian Morocco: A Discovery in Living Art (2 ed.). Ministère des Affaires Culturelles du Royaume du Maroc & Museum With No Frontiers. ISBN 978-3902782311.

- ^ Meri (2002), pp. 264–265.

- ^ Meri (2002), pp. 264.

- ^ "Tombs and Elevated Marking of Graves: What the Hadiths say and what the Wahhabiyya do not say". Aal-e-Qutub Aal-e-Syed Abdullah Shah Ghazi. 2018-04-10. Retrieved 2024-04-16.

- ^ Kreyenbroek, Philip (1995). Yezidism: its background, observances, and textual tradition. Lewiston NY: E. Mellen Press. ISBN 0773490043. OCLC 31377794.

Bibliography

[edit]- Jessup, Samuel (1881). "The Wady Barada". Picturesque Palestine, Sinai, and Egypt, Division II. New York: D. Appleton & Co. pp. 444–452.

- Meri, Josef F. (2002). "The cult of saints among Muslims and Jews in medieval Syria". Oxford Oriental Monographs. Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0199250783.

- Diez, E. (2010). "Ḳubba". Encyclopaedia of Islam, 2nd ed.. Leiden: Brill.. (subscription required)

- Petersen, Andrew (2001). A Gazetteer of Buildings in Muslim Palestine (British Academy Monographs in Archaeology). Vol. 1. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0197270110.