Ferdinand I of the Two Sicilies

Ferdinand I (12 January 1751 – 4 January 1825), was the King of the Two Sicilies from 1816, after his restoration following victory in the Napoleonic Wars. Before that he had been, since 1759, Ferdinand IV of the Kingdom of Naples and Ferdinand III of the Kingdom of Sicily. He was also King of Gozo. He was deposed twice from the throne of Naples: once by the revolutionary Parthenopean Republic for six months in 1799 and again by Napoleon in 1805, before being restored in 1816.

Ferdinand was the third son of King Charles VII of Naples and V of Sicily by his wife, Maria Amalia of Saxony. On 10 August 1759, Charles succeeded his elder brother, Ferdinand VI, becoming King Charles III of Spain, but treaty provisions made him ineligible to hold all three crowns. On 6 October, he abdicated his Neapolitan and Sicilian titles in favour of his third son, because his eldest son Philip had been excluded from succession due to illnesses and his second son Charles was heir-apparent to the Spanish throne. Ferdinand was the founder of the cadet House of Bourbon-Two Sicilies.

Childhood

Ferdinand was born in Naples and grew up amidst many of the monuments erected there by his father which can be seen today; the Palaces of Portici, Caserta and Capodimonte.

Ferdinand was his parents' third son, his elder brother Charles was expected to inherit Naples and Sicily. When his father ascended the Spanish throne in 1759 he abdicated Naples in Ferdinand's favor in accordance with the treaties forbidding the union of the two crowns. A regency council presided over by the Tuscan Bernardo Tanucci was set up. The latter, an able, ambitious man, wishing to keep the government as much as possible in his own hands, purposely neglected the young king's education, and encouraged him in his love of pleasure, his idleness and his excessive devotion to outdoor sports.[1][2]

Reign

Ferdinand's minority ended in 1767, and his first act was the expulsion of the Jesuits. The following year he married Archduchess Maria Carolina, daughter of Empress Maria Theresa. By the marriage contract the queen was to have a voice in the council of state after the birth of her first son, and she was not slow to avail herself of this means of political influence.[2]

Tanucci, who attempted to thwart her, was dismissed in 1777. The Englishman Sir John Acton, who in 1779 was appointed director of marine, won Maria Carolina's favour by supporting her scheme to free Naples from Spanish influence, securing rapprochement with Austria and Great Britain. He became practically and afterward actually prime minister. Although not a mere grasping adventurer, he was largely responsible for reducing the internal administration of the country to a system of espionage, corruption and cruelty.[2]

French Occupation and the Parthenopaean Republic

Although peace was made with France in 1796, the demands of the French Directory, whose troops occupied Rome, alarmed the king once more, and at his wife's instigation he took advantage of Napoleon's absence in Egypt and of Nelson's victories to go to war. He marched with his army against the French and entered Rome (29 November), but on the defeat of some of his columns he hurried back to Naples, and on the approach of the French, fled on 23 December 1798 aboard Nelson's ship HMS Vanguard to Palermo, Sicily, leaving his capital in a state of anarchy.[3][2]

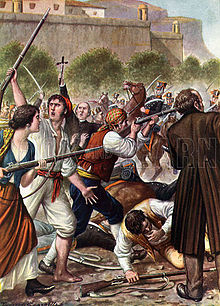

The French entered the city in spite of the fierce resistance of the lazzaroni, and with the aid of the nobles and bourgeoisie established the Parthenopaean Republic (January 1799). When, a few weeks later the French troops were recalled to northern Italy, Ferdinand sent a hastily assembled force, under Cardinal Ruffo, to reconquer the mainland kingdom. Ruffo, with the support of British artillery, the Church, and the pro-Bourbon aristocracy, succeeded, reaching Naples in May 1800, and the Parthenopaean Republic collapsed.[2] After some months King Ferdinand returned to the throne.

The king, and above all the queen, were particularly anxious that no mercy should be shown to the rebels, and Maria Carolina (a sister of the executed Marie Antoinette) made use of Lady Hamilton, Nelson's mistress, to induce Nelson to carry out her vengeance.[2]

Third Coalition

The king returned to Naples soon afterwards, and ordered a few hundred who had collaborated with the French executed. This stopped only when the French successes forced him to agree to a treaty which included amnesty for members of the French party. When war broke out between France and Austria in 1805, Ferdinand signed a treaty of neutrality with the former, but a few days later he allied himself with Austria and allowed an Anglo-Russian force to land at Naples (see Third Coalition).[2]

The French victory at the Battle of Austerlitz on 2 December enabled Napoleon to dispatch an army to southern Italy. Ferdinand fled to Palermo (23 January 1806), followed soon after by his wife and son, and on 14 February 1806 the French again entered Naples. Napoleon declared that the Bourbon dynasty had forfeited the crown, and proclaimed his brother Joseph King of Naples and Sicily. But Ferdinand continued to reign over the latter kingdom (becoming the first King of Sicily in centuries to actually reside there) under British protection.[2]

Parliamentary institutions of a feudal type had long existed in the island, and Lord William Bentinck, the British minister, insisted on a reform of the constitution on English and French lines. The king indeed practically abdicated his power, appointing his son Francis as regent, and the queen, at Bentinck's insistence, was exiled to Austria, where she died in 1814.[2]

Restoration

After the fall of Napoleon, Joachim Murat, who had succeeded Joseph Bonaparte as king of Naples in 1808, was dethroned in the Neapolitan War, and Ferdinand returned to Naples. By a secret treaty he had bound himself not to advance further in a constitutional direction than Austria should at any time approve; but, though on the whole he acted in accordance with Metternich's policy of preserving the status quo, and maintained with but slight change Murat's laws and administrative system, he took advantage of the situation to abolish the Sicilian constitution, in violation of his oath, and to proclaim the union of the two states into the kingdom of the Two Sicilies (12 December 1816).[2]

Ferdinand was now completely subservient to Austria, an Austrian, Count Nugent, being even made commander-in-chief of the army. For the next four years he reigned as an absolute monarch within his domain, granting no constitutional reforms.

1820 revolution

The suppression of liberal opinion caused an alarming spread of the influence and activity of the secret society of the Carbonari, which in time affected a large part of the army.[2] In July 1820 a military revolt broke out under General Guglielmo Pepe, and Ferdinand was terrorised into signing a constitution on the model of the Spanish Constitution of 1812. On the other hand, a revolt in Sicily, in favour of the recovery of its independence, was suppressed by Neapolitan troops.

The success of the military revolution at Naples seriously alarmed the powers of the Holy Alliance, who feared that it might spread to other Italian states and so lead to a general European conflagration. The Troppau Protocol of 1820 was signed by Austria, Prussia and Russia, although an invitation to Ferdinand to attend the adjourned Congress of Laibach (1821) was issued at which he failed to distinguish himself. He had twice sworn to maintain the new constitution but was hardly out of Naples before he repudiated his oaths and, in letters addressed to all the sovereigns of Europe, declared his acts to have been null and void. Metternich had no difficulty in persuading the king to allow an Austrian army to march into Naples "to restore order".[2]

The Neapolitans, commanded by General Pepe, made no attempt to defend the difficult defiles of the Abruzzi,[2] and were defeated at Rieti (7 March 1821). The Austrians entered Naples.

Later years

Following the Austrian victory, the Parliament was dismissed and Ferdinand suppressed the Liberals and Carbonari. The victory was used by Austria to force its grasp over Naples' domestic and foreign policies. Count Charles-Louis de Ficquelmont was appointed as the Austrian ambassador to Naples, practically administrating the country as well as managing the occupation and strengthening Austrian influence over Neapolitan elites.

Ferdinand died in Naples in January 1825. He was the last surviving child of Charles III.

Ferdinand I in cinema

- Ferdinando and Carolina (1999) directed by Lina Wertmüller

- Luisa Sanfelice (2004) directed by Paolo and Vittorio Taviani

Issue

| Children of Ferdinand I | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Name | Picture | Birth | Death | Notes |

| By Maria Carolina of Austria (Vienna, 13 August 1752 – Vienna, 8 September 1814) | ||||

| Maria Teresa Carolina Giuseppina |  |

6 June 1772 | 13 April 1807 | Named after her maternal grand mother Maria Theresa of Austria, she married her first cousin Francis II, Holy Roman Emperor in 1790; had issue. |

| Maria Luisa Amelia Teresa |  |

Royal Palace of Naples, 27 July 1773 | Hofburg Imperial Palace, 19 September 1802 | Married her first cousin Ferdinand III, Grand Duke of Tuscany and had issue. |

| Carlo Tito Francesco Giuseppe |  |

Naples, 6 January 1775 | 17 December 1778 | Died of smallpox. |

| Maria Anna Giuseppa Antonietta Francesca Gaetana Teresa |  |

23 November 1775 | 22 February 1780 | Died of smallpox. |

| Francesco Gennaro Giuseppe Saverio Giovanni Battista |  |

Naples, 14 August 1777 | Naples, 8 November 1830 | Married his cousin Archduchess Maria Clementina of Austria in 1797 and had issue; married another cousin Infanta Maria Isabella of Spain in 1802 and had issue; was King of the Two Sicilies from 1825 to 1830. |

| Maria Cristina Teresa |  |

Caserta Palace, 17 January 1779 | Savona, 11 March 1849 | Married Charles Felix of Sardinia in 1807; had no issue; it was she who ordered the excavations of Tusculum. |

| Gennaro Carlo Francesco |  |

Naples 12 April 1780 | 2 January 1789 | Died of smallpox. |

| Giuseppe Carlo Gennaro |  |

Naples, 18 June 1781 | 19 February 1783 | Died of smallpox. |

| Maria Amelia Teresa |  |

Caserta Palace, 26 April 1782 | Claremont House, 24 March 1866 | Married in 1809 Louis Philippe I, Duke of Orleans, King of the French and had issue. |

| Maria Cristina | Caserta Palace, 19 July 1783 | Caserta Palace, 19 July 1783 | Stillborn. | |

| Maria Antonietta Teresa Amelia Giovanna Battista Francesca Gaetana Maria Anna Lucia |  |

Caserta Palace, 14 December 1784 | Royal Palace of Aranjuez, 21 May 1806 | Married her cousin Infante Ferdinand, Prince of Asturias; died from tuberculosis; had no issue. |

| Maria Clotilde Teresa Amelia Antonietta Giovanna Battista Anna Gaetana Polcheria | Caserta Palace, 18 February 1786 | 10 September 1792 | Died of smallpox. | |

| Maria Enricheta Carmela | Naples, 31 July 1787 | Naples, 20 September 1792 | Died of smallpox. | |

| Carlo Gennaro | Naples, 26 August 1788 | Caserta Palace, 1 February 1789 | Died of smallpox. | |

| Leopoldo Giovanni Giuseppe Michele of Naples |  |

Naples, 2 July 1790 | Naples, 10 March 1851 | Married his niece Archduchess Clementina of Austria and had issue. |

| Alberto Lodovico Maria Filipo Gaetano |  |

2 May 1792 | Died on board HMS Vanguard, 25 December 1798 | Died in childhood (died of exhaustion on board HMS Vanguard). |

| Maria Isabella |  |

Naples, 2 December 1793 | 23 April 1801 | Died in childhood. |

Ancestry

| Ancestors of Ferdinand I of the Two Sicilies[4] | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Heraldry

- Heraldry of Ferdinand of Naples, Sicily and the Two Sicilies

-

Coat of arms as King of Naples

(1759–1799 / 1799–1806 /1814–1816)[5] -

Coat of arms as King of Sicily

(1759–1816)[5] -

Coat of arms as King of the Two Sicilies

(1816–1825)[5]

References

- ^ Rule in Naples interrupted during two periods:

• 23 January 1799 – 13 June 1799: brief Parthenopaean Republic proclaimed;

• 30 March 1806 – 22 May 1815: dethroned by Napoleon and replaced by Joseph Bonaparte.

- ^ Acton, Harold (1957). The Bourbons of Naples (1731-1825) (2009 ed.). London: Faber and Faber. p. 150. ISBN 9780571249015.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m One or more of the preceding sentences incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). "Ferdinand IV. of Naples". Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. 10 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. pp. 264–265.

- ^ Davis, John (2006). Naples and Napoleon: Southern Italy and the European Revolutions, 1780-1860. Oxford University Press. ISBN 9780198207559.

- ^ Genealogie ascendante jusqu'au quatrieme degre inclusivement de tous les Rois et Princes de maisons souveraines de l'Europe actuellement vivans [Genealogy up to the fourth degree inclusive of all the Kings and Princes of sovereign houses of Europe currently living] (in French). Bourdeaux: Frederic Guillaume Birnstiel. 1768. p. 9.

- ^ a b c "Le origini dello stemma delle Due Sicilie, Ferdinando IV, poi I". Storia e Documenti (in Italian). Real Casa di Borbone delle Due Sicilie. Archived from the original on 10 April 2013. Retrieved 24 March 2013.

Ď

- Kings of Sicily

- Monarchs of the Kingdom of the Two Sicilies

- Monarchs of Naples

- 1751 births

- 1825 deaths

- 18th-century Kings of Sicily

- 19th-century Kings of Sicily

- 18th-century monarchs of Naples

- 19th-century monarchs of Naples

- House of Bourbon-Two Sicilies

- Modern child rulers

- Knights of the Golden Fleece of Spain

- Neapolitan princes

- Sicilian princes

- Spanish infantes

- Dukes of Calabria

- Recipients of the Order of St. Andrew

- Grand Crosses of the Order of Saint Stephen of Hungary

- Italian Roman Catholics

- Burials at the Basilica of Santa Chiara

- 18th century in the Kingdom of Sicily

- 18th-century Roman Catholics

- 19th-century Roman Catholics

![Coat of arms as King of Naples (1759–1799 / 1799–1806 /1814–1816)[5]](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/6/6c/Greater_Coat_of_Arms_of_Ferdinand_IV_of_Naples.svg/175px-Greater_Coat_of_Arms_of_Ferdinand_IV_of_Naples.svg.png)

![Coat of arms as King of Sicily (1759–1816)[5]](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/5/5c/Coat_of_Arms_of_Ferdinand_III_of_Sicily.svg/175px-Coat_of_Arms_of_Ferdinand_III_of_Sicily.svg.png)

![Coat of arms as King of the Two Sicilies (1816–1825)[5]](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/c/ce/Great_Royal_Coat_of_Arms_of_the_Two_Sicilies.svg/153px-Great_Royal_Coat_of_Arms_of_the_Two_Sicilies.svg.png)