Burma campaign (1944–1945)

| Burma campaign 1944–1945 | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the Burma campaign during World War II | |||||||||

Two British soldiers patrol the ruins of Bahe, in Central Burma. | |||||||||

| |||||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||||

Allies

|

| ||||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||||

|

| ||||||||

The Burma campaign in the South-East Asian Theatre of World War II was fought primarily by British Commonwealth, Chinese and United States forces[5] against the forces of Imperial Japan, who were assisted to some degree by Thailand, the Burmese National Army and the Indian National Army. The British Commonwealth land forces were drawn primarily from the United Kingdom, British India and Africa.

Partly because monsoon rains made effective campaigning possible only for about half of the year, the Burma campaign was almost the longest campaign of the war. During the campaigning season of 1942, the Japanese had conquered Burma, driving British, Indian and Chinese forces from the country and forcing the British administration to flee into India. After scoring some defensive successes during 1943, they then attempted to forestall Allied offensives in 1944 by launching an invasion of India (Operation U-Go). This failed with disastrous losses.

During the next campaigning season beginning in December 1944, the Allies launched several offensives into Burma. American and Chinese forces advancing from northernmost Burma linked up with armies of the Chinese Republic advancing into Yunnan, which allowed the Allies to complete the Burma Road in the last months of the war. In the coastal province of Arakan, Allied amphibious landings secured vital offshore islands and inflicted heavy casualties, although the Japanese maintained some positions until the end of the campaign. In Central Burma however, the Allies crossed the Irrawaddy River and defeated the main Japanese armies in the theatre. Allied formations then followed up with an advance on Rangoon, the capital and principal port. Japanese rearguards delayed them until the monsoon struck but an Allied airborne and amphibious attack secured the city, which the Japanese had abandoned.

In a final operation just before the end of the war, Japanese forces which had been isolated in Southern Burma attempted to escape across the Sittang River, suffering heavy casualties.

Background

Allied plans

As the monsoon rains ended late in 1944, the Allies were preparing to launch large-scale offensives into Japanese-occupied Burma. The main Allied headquarters for the British, Indians and Americans in the theatre of war was South East Asia Command, based at Kandy in Ceylon and commanded by Admiral Louis Mountbatten. The command had considered three major plans as far back as July 1944.[6]

- Plan "X": The main effort was to be made by the American-led Northern Combat Area Command, with support from the British Fourteenth Army. Starting from Mogaung and Myitkyina which had been captured in mid-1944, the NCAC would link up with the Chinese National Revolutionary Army attacking from Yunnan province under General Wei Lihuang about Lashio. The aim was to complete the Ledo Road, which would link Assam in north-east India with Yunnan, supplementing The Hump airlift which delivered aid and war material to China.

- Plan "Y": The major effort was to be made by Fourteenth Army, across the Chindwin River into Central Burma, with the aim of capturing Mandalay and linking up with the NCAC and Yunnan Chinese around Maymyo, about 20 miles (32 km) east of Mandalay

- Plan "Z": Under this plan, which would later be developed into Operation Dracula, the main effort would be an amphibious and airborne attack on Rangoon, the capital and principal port of Burma. If successful, this would isolate the Japanese in Burma from their lines of communication and force them to evacuate the country.

When these plans were studied, it was found that the resources required for Plan "Z" (landing craft, aircraft carrier groups etc.) would probably not be made available until the war in Europe was won. Mountbatten nevertheless proposed to attempt Plans "Y" and "Z" simultaneously but Plan "Y" was adopted and renamed Operation Capital. Under this, Fourteenth Army (supported by 221 Group RAF) would make the major offensive into Central Burma, where the terrain and road network favoured the British and Indian armoured and motorised formations. The NCAC and Yunnan Chinese (supported by the United States Tenth and Fourteenth Air Forces) would make subsidiary advances to Lashio, while the XV Corps (supported by 224 Group RAF) would seize the coastal province of Arakan, securing or constructing airfields which could be used to supply Fourteenth Army.[7]

Japanese plans

In the aftermath of their defeats the previous year, the Japanese had made major changes in their command. The most important was the appointment of Lieutenant General Hyotaro Kimura to command Burma Area Army, succeeding General Masakazu Kawabe. Kimura was primarily a logistician who had previously been Vice-Minister of War and it was hoped that he could use the natural and industrial resources of Burma to make his army self-sufficient. Nevertheless, the Southern Expeditionary Army Group, which had overall control of all Japanese land forces in Southern Asia and much of the Pacific Ocean and was commanded by Field Marshal Hisaichi Terauchi, found 60,000 reinforcements for Kimura's army, with equipment for three infantry divisions and 500 lorries and 2000 pack animals for the lines of communication. Allied air attacks strangled the Japanese communications via the Burma Railway and the port of Rangoon and only 30,000 of the intended reinforcements reached Burma. Under pressure of events in the Pacific, Terauchi even withdrew some units from Burma during the campaign.[8]

Although the Allies expected that the Japanese would fight as far forward as possible, on the Chindwin, Kimura recognised that most of the Japanese units in Burma were weakened by heavy casualties during the previous year and were short of equipment. To avoid fighting at a disadvantage on the Chindwin or in the Shwebo plain between the Chindwin and Irrawaddy River where the terrain provided comparatively few obstacles to the British and Indian armoured and motorised units, he withdrew Fifteenth Army behind the Irrawaddy, which they would defend against the British Fourteenth Army (Operation BAN). The Twenty-Eighth Army was to continue to defend the Arakan and lower Irrawaddy valley (Operation KAN), while Thirty-Third Army would attempt to prevent the completion of the new road link between India and China by defending the cities of Bhamo and Lashio and mounting guerilla raids (Operation DAN).[9]

Burma

Another factor which was to become significant during the campaign was the changing attitude of the Burmese population. During the Japanese invasion of Burma in 1942, many of the majority Bamar population had actively aided the Japanese Army. Although the Japanese had established a nominally independent Burmese government (the State of Burma) under Ba Maw and formed a Burma National Army under Aung San, they remained in effective control of the country. Their strict control, along with wartime privations, turned the Burmese against them.

Aung San had sought an alliance with Thakin Soe, who was leading a Communist insurgency in southern Arakan, as early as 1943. They formed the Anti-Fascist Organisation and intended turning against the Japanese at some stage but Thakin Soe dissuaded Aung San from openly rebelling until Allied forces had established permanent footholds in Burma. In early 1945, Aung San sought the aid of the Allied liaison organisation Force 136, which was already aiding resistance movements among the minority Karen population. Although there was some debate among the Allies, Mountbatten eventually decided that Aung San should be supported. Force 136 was now to abet the defection of the entire Burma National Army to the Allies.[10]

Another force nominally under Japanese control was the Indian National Army, a force mainly composed of former prisoners of war and volunteers from the Indian expatriate communities in British Malaya and Burma. Its commander in chief was Subhas Chandra Bose. During the 1945 campaign, some INA units fought stoutly against the Allies but others deserted or capitulated readily. The Japanese had alienated many of the INA by denying them equipment and supplies, or by using them as labourers and carriers rather than as fighting troops. Their morale was also affected in some units by the obvious turn of fortune against the Japanese.

Southern front

The Japanese Twenty-eighth Army, commanded by Lieutenant General Shozo Sakurai, defended the coastal Arakan region and the lower Irrawaddy valley. The Japanese 54th Division defended the Mayu Peninsula and Kaladan River valley, the Japanese 55th Division garrisoned several ports and part of southern Burma (with a regiment on Mount Popa) and the 72nd Independent Mixed Brigade was stationed around the oilfields at Yenangyaung on the Irrawaddy.[11]

The Allied forces in Arakan were controlled by the XV Indian Corps under Lieutenant General Philip Christison. The Corps' first major objective was Akyab Island, at the end of the Mayu Peninsula. The island held a port and an important airfield which the Allies planned to use as a base from which to deliver supplies by air to the troops in Central Burma. An attempt to capture the island in 1943 had been defeated, a second attempt in early 1944 gained some ground but was abandoned because of monsoon rains and lack of resources.

As the monsoon ended in late 1944, XV Corps resumed the advance on Akyab for the third year in succession. The 25th Indian Division advanced on Foul Point and Rathedaung at the end of the Mayu Peninsula, being supplied by landing craft over beaches to avoid the risk of Japanese attacks against their lines of communication. The 82nd (West Africa) Division cleared the valley of the Kalapanzin River before crossing a mountain range into the Kaladan River valley, while the 81st (West Africa) Division advanced down the Kaladan River, repeating the move it had made in early 1944. The two African divisions converged on Myohaung near the mouth of the Kaladan River, cutting the supply lines of the Japanese troops in the Mayu Peninsula. The Japanese evacuated Akyab Island on 31 December 1944. It was occupied by XV Corps without resistance two days later.

The 82nd Division next attacked south along the coastal plain, while the 25th Indian Division, with 3 Commando Brigade under command, made amphibious landings further south to catch the Japanese in a pincer movement. First ashore was No. 42 (Royal Marine) Commando on the south-eastern face of the Myebon Peninsula on 12 January 1945. Over the next few days the commandos and a brigade of 25th Division cleared the peninsula and denied the Japanese the use of the many waterways along the Arakan coast.

On 22 January, 3 Commando Brigade landed on the beaches at Daingbon Chaung led this time by No. 1 Commando. Having secured the beaches they moved inland and became involved in very heavy fighting with the Japanese. The following night a brigade of the 25th Division was landed in support. The fighting around the beachhead involved hand-to-hand fighting as the Japanese realised the danger of encirclement and threw all their available troops into the fight. The commandos and Indian troops managed to turn the tide of the battle and take the village of Kangaw only on 29 January. Meanwhile, the forces on the Myebon Peninsula linked up with the 82nd Division fighting its way overland towards Kangaw. Caught between the 82nd Division and the forces already in Kangaw, the Japanese were forced to scatter, leaving behind thousands of dead and most of their heavy equipment.

With the coastal area secured, the Allies were free to build airbases which could be supplied by sea on the two offshore islands, Ramree Island and Cheduba Island. Cheduba, the smaller of the two islands, had no Japanese garrison but the Battle of Ramree Island lasted for six weeks after the initial landings on 21 January by the 26th Indian Division before the survivors of the small but tenacious Japanese garrison withdrew from the island,[12][13] suffering heavy casualties to disease, starvation, Allied Motor Launches and other naval vessels and (allegedly) crocodiles.[14]

Following these actions, XV Corps' operations were curtailed to release transport aircraft to support Fourteenth Army. The 81st Division and the 50th Indian Tank Brigade were withdrawn to India. Outflanking moves by the 82nd Division and 26th Indian Division through the hills around An and Taungup were abandoned or cancelled and the Corps' divisions were withdrawn to the coast. The Japanese successfully defended the port of Taungup and the An and Taungup passes across the Arakan hills until very late in the campaign.

Northern front

The Japanese Thirty-third Army, led by Lieutenant General Masaki Honda, defended Northern Burma against attacks from both Northern India and the Chinese province of Yunnan. The Japanese 18th Division faced the American and Chinese Northern Combat Area Command (NCAC) under Lieutenant General Daniel Isom Sultan advancing south from Myitkyina and Mogaung which the Allies had secured in 1944, while the Japanese 56th Division faced the large Chinese Yunnan armies led by Wei Lihuang.

Although Thirty-third Army had been forced to relinquish most of the reinforcements it had received the previous year, the operations of the NCAC were limited from late 1944 onwards as many of its troops were withdrawn by air to face Japanese attacks in China. In Operation Grubworm, the Chinese 14th and 22nd divisions were flown via Myitkyina to defend the airfields around Kunming, vital to the airlift of aid to China, nicknamed The Hump. Nevertheless, the command resumed its advance.

On the right flank of the command, the British 36th Division, which had been assigned to the command in July 1944 to replace the Chindits, advanced south down the "Railway Valley" from Mogaung to Indaw. It made contact with the 19th Indian Division near Indaw on 10 December 1944 and Fourteenth Army and NCAC now had a continuous front. On Sultan's left, the Chinese New First Army, commanded by Sun Li-jen and consisting of the 30th Division and 38th Division, advanced from Myitkyina to Bhamo. The Japanese resisted for several weeks but Bhamo fell on 15 December. The Chinese New Sixth Army, commanded by Liao Yaoxiang and consisting of the 50th Division, infiltrated through the difficult terrain between these two wings to threaten the Japanese lines of communication.

The American 5334th Composite Unit, known as the "Mars Brigade", had replaced Merrill's Marauders. The unit was commanded by Brigadier General J. P. Willey and consisted of the 475th United States Infantry Regiment, the 124th United States Cavalry Regiment and the elite Chinese 1st Regiment. They attempted to cut the Burma Road behind the Japanese 56th Division. They failed to isolate the Japanese division but hastened its retreat.[15]

Sun Li-Jen's New First Army made contact with Wei Lihuang's armies advancing from Yunnan near Hsipaw on 21 January 1945 and the Ledo road could finally be completed. The first truck convoy from India arrived in Kunming on 4 February[16] but by this point in the war the value of the Ledo road was uncertain, as it would not now affect the military situation in China.

To the annoyance of the British and Americans, Chinese leader Chiang Kai-shek ordered Sultan to halt his advance at Lashio, which was captured on 7 March. The British and Americans generally refused to understand that Chiang had to balance the needs of China as a whole against fighting the Japanese in a British colony.[citation needed] The Japanese had already withdrawn the 18th Division from the northern front, to face the Fourteenth Army in central Burma. On 12 March, the Thirty-third Army HQ was also dispatched there, leaving only the 56th Division to hold the northern front.[17] This division was also withdrawn in late March and early April.

From 1 April, NCAC's operations stopped and its units returned to China. The British 36th Division moved to Mandalay, which had been captured in March and was subsequently withdrawn to India. A US-led guerrilla force, OSS Detachment 101, took over the military responsibilities of NCAC,[16] while British civil affairs and other units such as the Civil Affairs Service (Burma) stepped in to take over its other responsibilities. Northern Burma was partitioned into Line-of-Communication areas by the military authorities.

Central front

The Japanese Fifteenth Army, commanded by Lieutenant General Shihachi Katamura, held the central part of the front. The army was falling back behind the Irrawaddy, deploying rearguards to delay the Allied advance. A bridgehead was retained in the Sagaing hills.

The Fifteenth Army consisted of the Japanese 15th Division, 31st Division and the 33rd Division. The 53rd Division provided a reserve, although it was controlled directly by the Burma Area Army. During the campaign, the headquarters of the Japanese Thirty-third Army and parts of the 2nd Division and the 49th Division reinforced the forces on the central part of the front.

The British Fourteenth Army under Lieutenant General William Slim made the main Allied thrust, codenamed Operation Capital, into central Burma. It consisted of IV Corps under Lieutenant General Frank Messervy and XXXIII Corps under Lieutenant General Montagu Stopford, together controlling six infantry divisions, two armoured brigades and three independent infantry brigades. The main constraint on the number of forces the Fourteenth Army could deploy was supply. A carefully designed system involving large amounts of air transport was introduced and major construction projects were undertaken to improve the land route from India into Burma and make use of river transport.

Units of both corps of the Fourteenth Army crossed the Chindwin and attacked into the Shwebo plain, IV Corps on the left and XXXIII Corps on the right. After a few days, when it was realised that the Japanese had fallen back behind the Irrawaddy River, the plan was hastily changed. Now, only XXXIII Corps was to continue the attack into the Shwebo Plain, reinforced by the one division of IV Corps which had been committed across the Chindwin, while the main body of IV Corps was switched to the right flank, changing its axis of advance to the Gangaw Valley west of the Chindwin. It aimed to cross the Irrawaddy close to Pakokku and then capture the main Japanese line of communication centre of Meiktila. Diversionary measures (such as dummy radio traffic) were made to persuade the Japanese that both corps were still aimed at Mandalay. The new plan was a success. Allied air superiority and the thin Japanese presence on the ground meant that the Japanese were unaware of the strength of the force moving on Pakokku.

During January and February, the XXXIII Corps (consisting of the British 2nd Division, 19th Indian Division, 20th Indian Division, 268th Indian Brigade and the 254th Indian Tank Brigade) cleared the Shwebo plain and established bridgeheads over the Irrawaddy River near Mandalay. There was heavy fighting, which attracted Japanese reserves and fixed their attention. Late in February, the 7th Indian Division, leading IV Corps, seized crossings at Nyaungu and Pagan near Pakokku. While the 28th (East Africa) Infantry Brigade maintained diversionary pressure against Yenangyaung on the west bank of the river, the 17th Indian Division and the 255th Indian Armoured brigade crossed through 7th Indian Division's bridgeheads and began advancing to Meiktila.

Meiktila

In the dry season, central Burma is largely an open plain with sandy soil and there is also a good road network. The mechanised 17th Indian Division and the armoured brigade could move rapidly and unhindered in this open terrain, apparently taking the staffs at the various Japanese headquarters by surprise with this blitzkrieg manoeuvre. Reinforced by the third brigade of the 17th Indian Division which flew in to a captured airstrip, they struck Meiktila on 1 March and captured it in four days, despite resistance to the last man. In an oft-recounted incident, some Japanese soldiers crouched in trenches with aircraft bombs, with orders to detonate them when an enemy tank loomed over the trench.

Japanese reinforcements arrived too late to relieve the garrison but they besieged the town in an attempt to recapture it and destroy the 17th Indian Division. Although eight Japanese regiments were eventually involved, they were mostly weak in numbers and drawn from five divisions, so their efforts were not coordinated. The Japanese Thirty-third Army HQ (re-titled The Army of the Decisive Battle) was assigned to take command in this vital sector but was unable to establish proper control.[17] The 17th Indian Division had been reinforced by a brigade of the 5th Indian Division landed by air. British tank-infantry forces sallied out of Meiktila to break up Japanese concentrations and by the end of the month the Japanese had suffered heavy casualties and had lost most of their artillery, their chief anti-tank weapon. The Japanese broke off the attack and retreated to Pyawbwe.

While the capture and siege of Meiktila took place, the 7th Indian Division, reinforced by a mechanised brigade of the 5th Indian Division, secured the Irrawaddy bridgehead, captured the important river port at Myingyan and began clearing the lines of communication to Meiktila.

Mandalay

While the Japanese were distracted by events at Meiktila, XXXIII Corps had renewed its attack on Mandalay. It fell to the 19th Indian Division on 20 March, though the Japanese held the former citadel, which the British called Fort Dufferin, for another week. Many of the historically and culturally significant areas of Mandalay, including the old royal palace, were burned to the ground. A great deal was lost by the Japanese choice to make a last stand in the city itself. The other divisions of XXXIII Corps simultaneously attacked from their bridgeheads across the Irrawaddy. The Japanese Fifteenth Army was reduced to small detachments and parties of stragglers making their way south, or east into the Shan States. With the fall of Mandalay (and of Maymyo to its east), the Japanese communications to the front in the north of Burma were cut and the Allied road link between India and China was therefore finally secured, though far too late to affect the course of the war in China.

The fall of Mandalay also precipitated the change of sides by the Burma National Army and open rebellion against the Japanese by other underground movements belonging to the Anti-Fascist Organisation.[18] In the last week of March Aung San, commander-in-chief of the Burma National Army, appeared in public in Burmese native dress instead of Japanese uniform.[19] Shortly afterwards, most of the Burma National Army paraded in Rangoon and then marched out of the city as if going to the front in Central Burma. They then rebelled against the Japanese on 27 March.[20]

Race for Rangoon

Though the Allied force had advanced successfully into central Burma, it was vital to capture the port of Rangoon before the monsoon rains began. The temporarily upgraded overland routes from India would disintegrate under heavy rain, which would also curtail flying and reduce the amount of supplies which could be delivered by air. Furthermore, South East Asia Command had been notified that many of the American transport aircraft allocated to the theatre would be withdrawn in June at the latest. The use of Rangoon would be necessary to meet the needs of the large army force and (as importantly) the food needs of the civilian population in the areas liberated.

The British 2nd Division and British 36th Division, both of which were understrength and could not readily be reinforced, were withdrawn to India to reduce the demand for supplies. (The 36th Division also exchanged the Indian battalions in one of its brigades for the depleted British battalions in the 20th Indian Division). The Indian XXXIII Corps, consisting of the 7th Indian Division and 20th Indian Division, mounted the Fourteenth Army's secondary drive down the Irrawaddy River valley, against the Japanese Twenty-Eighth Army. The IV Corps, of the 5th, 17th and 19th Indian divisions, made the main attack down the Sittang River valley.

The 17th Indian Division and 255th Armoured Brigade began the IV Corps advance on 6 April by striking from all sides at the delaying position held by the remnants of the Japanese Thirty-third Army at Pyawbwe, while a flanking column (nicknamed "Claudcol") of tanks and mechanised infantry cut the main road behind them and attacked their rear.[21] This column was initially delayed by the remnants of the Japanese 49th Division defending a village but bypassed them to defeat the remnants of the Japanese 53rd Division and destroy the last tanks remaining to the Japanese 14th Tank regiment. As they then turned north against the town of Pyawbwe itself, they attacked Lieutenant General Honda's headquarters but were not aware of the presence of an army headquarters and broke off to capture the town instead.[22]

From this point, the advance down the main road to Rangoon faced little organised opposition. At Pyinmana, the town and the bridge were seized on 19 April before the Japanese could organise their defence. The Japanese Thirty-third Army headquarters was present in Pyinmana. From reports by agents, the Allies were aware this time of Honda's presence and his headquarters was attacked by tanks and aircraft. Lieutenant-General Honda and his staff escaped at night on foot but they now had little means of controlling the remnants of their formations.[23]

Some units of the Japanese Fifteenth Army had reorganised in the Shan States and were reinforced by the Japanese 56th Division, which had been transferred from the northern front. They were ordered to move to Toungoo to block the road to Rangoon but a general uprising by Karen forces who had been organised and equipped by Force 136 delayed them long enough for the 5th Indian Division to reach the town first on 23 April. The Japanese briefly recaptured Toungoo once the 5th Indian Division had passed through but the 19th Indian Division, which was following up the leading units of IV Corps, captured the town again and slowly drove the Japanese back towards Mawchi to the east.

The 17th Indian Division resumed the lead of the advance and met a Japanese blocking force north of Pegu, 40 miles (64 km) north of Rangoon, on 25 April. The various line of communication troops, naval personnel and even Japanese civilians in Rangoon had been formed into the Japanese 105 Independent Mixed Brigade. This scratch formation used anti-tank mines improvised from aircraft bombs, anti-aircraft guns and suicide attacks with pole charges to delay the 17th Indian Division and then defended Pegu until 30 April, when it withdrew into the hills west of Pegu. The monsoon broke as the division resumed its advance on Rangoon and floods slowed the division.

Operation Dracula

In the original conception of the plan to re-take Burma, it had been intended that the XV Indian Corps would make an amphibious assault codenamed Operation Dracula on Rangoon long before Fourteenth Army reached the capital, in order to ease supply problems. Lack of resources meant that Dracula was postponed and the operation was subsequently dropped in favour of a planned assault on Phuket Island off the Kra Isthmus.

Slim feared that the Japanese would defend Rangoon to the last man through the monsoon, which would put the Fourteenth Army in a disastrous supply situation. In late March, he therefore asked for Dracula to be reinstated at short notice. However, Kimura had ordered Rangoon to be evacuated, starting on 22 April. Many troops were evacuated by sea, although British destroyers claimed several ships. Kimura's own HQ and the establishments of Ba Maw and Subhas Bose left by land, covered by the action of 105 Mixed Brigade at Pegu and proceeded to Moulmein.

On 1 May, a Gurkha parachute battalion was dropped on Elephant Point and cleared Japanese coastal defence batteries at the mouth of the Rangoon River. The 26th Indian Division started to land the next day as the monsoon began and took over Rangoon, which had seen an orgy of looting and lawlessness since the Japanese had left. The leading troops of the 17th and 26th Indian divisions met at Hlegu, 28 miles (45 km) north of Rangoon, on 6 May.

Final operations

Following the capture of Rangoon, a new Twelfth Army headquarters, commanded by Lieutenant General Stopford, was created from the XXXIII Indian Corps HQ to take control of the allied formations which were to remain in Burma, including IV Corps.

The remnants of the Japanese Burma Area Army remained in control of Tenasserim province. The Japanese Twenty-eighth Army, which had withdrawn from Arakan and unsuccessfully resisted XXXIII Corps in the Irrawaddy valley, and the 105 Independent Brigade, were cut off in the Pegu Yomas, a range of low jungle-covered hills between the Irrawaddy and Sittang rivers. They planned to break out and rejoin Burma Area Army. To cover this break-out, Kimura ordered Honda's Thirty-third Army to mount a diversionary offensive across the Sittang, although the entire army could muster the strength of barely a regiment. On 3 July, Honda's troops attacked British positions in the "Sittang Bend". On 10 July, after a battle for country which was almost entirely under chest-high water, both the Japanese and the 89th Indian Brigade withdrew.

Honda, pressed by Kimura and his chief of staff, Tanaka, had attacked too early. Sakurai's Twenty-eighth Army was not ready to start the break-out until 17 July. The break-out was a disaster. The British had captured the Japanese plans from an officer killed making a final reconnaissance,[24] and had placed ambushes or artillery concentrations on the routes they were to use. Hundreds of men drowned trying to cross the swollen Sittang on improvised bamboo floats and rafts. Burmese guerrillas and bandits killed stragglers east of the river. The break-out cost the Japanese nearly 10,000 men, half the strength of Twenty-eighth Army. Some units of 105 Independent Brigade were almost entirely wiped out.[25] British and Indian casualties were minimal.

Fourteenth Army (now commanded by Lieutenant General Miles Dempsey) and XV Corps had returned to India to plan the next stage of the campaign to re-take south east Asia. A new corps, the XXXIV Corps under Lieutenant-General Ouvry Lindfield Roberts, was raised and assigned to Fourteenth Army for further operations.

The next intended operation was to be an amphibious assault on the western coast of Malaya, codenamed Operation Zipper. The dropping of the atomic bombs forestalled Zipper but the operation was undertaken post-war as the quickest way of getting occupation troops into Malaya.

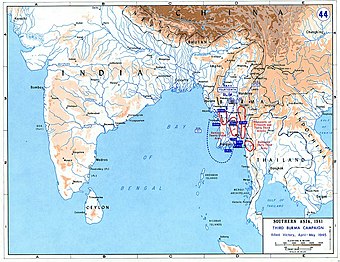

Maps

-

Third Burma campaign, October 1943 – May 1944

-

Third Burma campaign, June 1944 – April 1945

-

Third Burma campaign, April–May 1945

Notes

- ^ Not counting casualties fighting Americans and Chinese

Footnotes

- ^ Whelpton, John (2005). A History of Nepal (4th ed.). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. p. 67. ISBN 978-0-52180026-6.

- ^ Singh, S. B. (1992). "Nepal and the World Warii". Proceedings of the Indian History Congress. 53: 580–585. JSTOR 44142873.

- ^ The Burma Boy, Al Jazeera Documentary, Barnaby Phillips follows the life of one of the forgotten heroes of World War II, Al Jazeera Correspondent Last Modified: 22 July 2012 07:21,

- ^ "Survey of Allied tank casualties in World War II", Technical Memorandum ORO-T-117, Department of the Army, Washington D.C.,Table 1.

- ^ Video: Campaign in Burma, 1944/04/24 (1944). Universal Newsreel. 1944. Retrieved 22 February 2012.

- ^ Slim 1956, pp. 368–369.

- ^ Slim 1956, p. 368.

- ^ Allen 2005, p. 391.

- ^ Allen 2005, p. 392.

- ^ Bayly & Harper 2005, pp. 429–432

- ^ Allen 2005, p. 456.

- ^ Slim 1956, pp. 461–462

- ^ "No 5 Commando". Combined Operations. Retrieved 18 July 2019.

- ^ McLynn 2011, pp. 13–15, 459.

- ^ "The U.S. Army campaigns of World War II: Central burma". p. 7. Retrieved 4 May 2020.

- ^ a b Allen 2005, p. 455.

- ^ a b Allen 2005, p. 450.

- ^ Allen 2005, p. 573.

- ^ Allen 2005, p. 582.

- ^ Allen 2005, p. 584.

- ^ Allen 2005, p. 461.

- ^ Allen 2005, pp. 465–466.

- ^ Allen 2005, pp. 468–471.

- ^ Allen 2005, pp. 506–507.

- ^ Allen 2005, pp. 524–525.

References

- Allen, Louis (2005) [1984]. Burma: The longest War. Dent Publishing. ISBN 0-460-02474-4.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: ref duplicates default (link) - Bayly, Christopher; Harper, Tim (2005). Forgotten Armies: Britain's Asian Empire and the War with Japan. Penguin. ISBN 0-14-029331-0.

- McLynn, Frank (2011). The Burma Campaign: Disaster Into Triumph, 1942–45. Yale Library of Military History. New Haven: Yale University Press. ISBN 978-0-300-17162-4.

- Slim, William (1956). Defeat Into Victory: An Account of the Burma campaign, 1942–45 with Maps and a Portrait. London: Cassell. OCLC 843081328.

Further reading

- Fraser, George MacDonald (1993). Quartered Safe Out Here. London: Harvill. ISBN 978-0-00-710593-9.

- Hickey, Michael (1992). The Unforgettable Army. Tunbridge Wells: Spellmount. ISBN 1-873376-10-3.

- Hodsun, J. L. (1943). War in the Sun. London: Victor Gollancz. OCLC 222241837.

- Hogan, David W. (1992). India-Burma. The US Army Campaigns of World War II. CMH Pub 72-5. Washington: United States Army Center of Military History. OCLC 30476399.

- Jackson, Ashley (2006). The British Empire and the Second World War. London: Hambledon Continuum. ISBN 978-1-85285-517-8.

- Keegan, John, ed. (1991). Churchill's Generals. London: Cassell Military. ISBN 0-304-36712-5.

- "Operations in Burma from 12 November 1944 to 15 August 1945, official despatch by Lieutenant General Sir Oliver Leese". The London Gazette (Supplement). No. 39195. 6 April 1951. pp. 1881–1963.

- Latimer, Jon (2004). Burma: The Forgotten War. London: John Murray. ISBN 978-0-7195-6576-2.

- MacGarrigle, George L. (2000). Central Burma 29 January – 15 July 1945. The US Army Campaigns of World War II. CMH Pub 72-37. Washington, DC: United States Army Center of Military History. OCLC 835432028.

- Masters, John (1961). The Road Past Mandalay: A Personal Narrative. London: Michael Joseph. OCLC 922224518.

- Moser, Don (1978). World War II: China-Burma-India. Alexandria, VA: Time-Life Books. ISBN 978-0-8094-2484-9.

- Newell, Clayton R. (1995). Burma 1942. The US Army Campaigns of World War II. CMH Pub 72-21. Washington, DC: United States Army Center of Military History. ISBN 978-0-16-042086-3.

- Webster, Donovan (2003). The Burma Road: The Epic Story of the China-Burma-India Theater in World War II. New York: Farrar, Straus and Giroux. ISBN 978-0-374-11740-5.

- Woodburn Kirby, Major-General S. (2004) [1st. pub. HMSO 1958]. Butler, Sir James (ed.). The War Against Japan: India's Most Dangerous Hour. History of the Second World War. United Kingdom Military Series. Vol. II (facsimile ed.). Uckfield: Imperial War Museum and Naval & Military Press. ISBN 978-1-84574-061-0.

- Woodburn Kirby, Major-General S. (2004) [1st. pub. HMSO 1961]. Butler, Sir James (ed.). The War Against Japan: The Decisive Battles. History of the Second World War. United Kingdom Military Series. Vol. III (facsimile ed.). Uckfield: Imperial War Museum and Naval & Military Press. ISBN 978-1-84574-061-0.

- Woodburn Kirby, S. (2004) [1st. pub. HMSO 1968]. Butler, Sir James (ed.). The War Against Japan: The Reconquest of Burma. History of the Second World War. United Kingdom Military Series. Vol. IV (facsimile ed.). Uckfield: Imperial War Museum and Naval & Military Press. ISBN 978-1-84574-063-4.

External links

- Burma Star Association

- national-army-museum.ac.uk History of the British Army: Far East, 1941–45

- Imperial War Museum London Burma Summary

- Royal Engineers Museum Engineers in the Burma Campaigns

- Royal Engineers Museum Engineers with the Chindits

- Canadian War Museum: Newspaper Articles on the Burma Campaigns, 1941–1945

- World War II animated campaign maps

- List of Regimental Battle Honours in the Burma Campaign (1942–1945) – Also some useful links