Charles Manson

Charles Manson | |

|---|---|

Manson in 1968 | |

| Born | Charles Milles Maddox November 12, 1934 Cincinnati, Ohio, U.S. |

| Died | November 19, 2017 (aged 83) Bakersfield, California, U.S. |

| Other names | Charlie Manson |

| Known for | Manson Family murders |

| Spouses | Rosalie Willis

(m. 1955; div. 1958)Leona Stevens

(m. 1959; div. 1963) |

| Children | 2 |

| Criminal charge | 9 counts of murder, 1 count of conspiracy to commit murder |

| Penalty | |

| Partner(s) | Members of the Manson Family, including Susan Atkins, Mary Brunner and Tex Watson |

| Details | |

| Victims | 2 murdered, 7 murdered by proxy, 4 arsons |

| Signature | |

| |

Charles Milles Manson (né Maddox; November 12, 1934 – November 19, 2017) was an American criminal and musician who led the Manson Family, a cult based in California, in the late 1960s. Some of the members committed a series of nine murders at four locations in July and August 1969. In 1971, Manson was convicted of first-degree murder and conspiracy to commit murder for the deaths of seven people, including the film actress Sharon Tate. The prosecution contended that, while Manson never directly ordered the murders, his ideology constituted an overt act of conspiracy.[1]

Before the murders, Manson had spent more than half of his life in correctional institutions. While gathering his cult following, Manson was a singer-songwriter on the fringe of the Los Angeles music industry, chiefly through a chance association with Dennis Wilson of the Beach Boys, who introduced Manson to record producer Terry Melcher. In 1968, the Beach Boys recorded Manson's song "Cease to Exist", renamed "Never Learn Not to Love" as a single B-side, but without a credit to Manson. Afterward, Manson attempted to secure a record contract through Melcher, but was unsuccessful.

Manson would often talk about the Beatles, including their eponymous 1968 album. According to Los Angeles County District Attorney, Vincent Bugliosi, Manson felt guided by his interpretation of the Beatles' lyrics and adopted the term "Helter Skelter" to describe an impending apocalyptic race war. During his trial, Bugliosi argued that Manson had intended to start a race war, although Manson and others disputed this. Contemporary interviews and trial witness testimony insisted that the Tate–LaBianca murders were copycat crimes intended to exonerate Manson's friend Bobby Beausoleil.[2][3] Manson himself denied having instructed anyone to murder anyone.

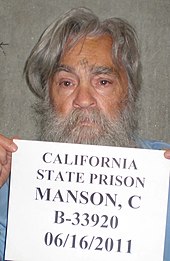

Manson's notoriety was an emblem of insanity, violence, and the macabre influenced pop culture. Recordings of songs written and performed by Manson were released commercially, starting with Lie: The Love and Terror Cult (1970). After his incarceration, some of his songs were covered by various artists. Although he was originally sentenced to death in 1971, his sentence was commuted to life with the possibility of parole after the California Supreme Court invalidated the state's death penalty statute in 1972. He served his life sentence at the California State Prison, Corcoran, and died at age 83 in late 2017.

1934–1967: Early life

Childhood

Charles Manson was born on November 12, 1934, to fifteen-year-old Kathleen Manson-Bower-Cavender, née Maddox (1919–1973),[4][5] in the University of Cincinnati Academic Health Center in Cincinnati, Ohio. He was named Charles Milles Maddox.[6][7]

Manson's biological father appears to have been Colonel Walker Henderson Scott Sr. (1910–1954)[8] of Catlettsburg, Kentucky, against whom Kathleen Maddox filed a paternity suit that resulted in an agreed judgment in 1937.[9] Scott worked intermittently in local mills, and had a local reputation as a con artist. He allowed Maddox to believe that he was an army colonel, although "Colonel" was merely his given name. When Maddox told Scott that she was pregnant, he told her he had been called away on army business; after several months she realized he had no intention of returning.[10] Manson may never have known his biological father.[11][page needed]

In August 1934, before Manson's birth, Maddox married William Eugene Manson (1909–1961), a "laborer" at a dry cleaning business. Maddox often went on drinking sprees with her brother Luther, leaving Charles with multiple babysitters. They divorced on April 30, 1937, after William alleged "gross neglect of duty" by Maddox. Charles retained William's last name, Manson.[12] On August 1, 1939, Luther and Kathleen Maddox were arrested for assault and robbery. Kathleen and Luther were sentenced to five and ten years of imprisonment, respectively.[13]

Manson was placed in the home of an aunt and uncle in McMechen, West Virginia.[14] His mother was paroled in 1942. Manson later characterized the first weeks after she returned from prison as the happiest time in his life.[15] Weeks after Maddox's release, Manson's family moved to Charleston, West Virginia,[16] where Manson continually played truant and his mother spent her evenings drinking.[17] She was arrested for grand larceny, but not convicted.[18] The family later moved to Indianapolis, where Maddox met an alcoholic with the last name "Lewis" through Alcoholics Anonymous meetings, and married him in August 1943.[17]

First offenses

In an interview with Diane Sawyer, Manson said that when he was nine, he set his school on fire.[19] Manson also got in trouble for truancy and petty theft. Although there was a lack of foster home placements, in 1947, at the age of 13, Manson was placed in the Gibault School for Boys in Terre Haute, Indiana, a school for male delinquents run by Catholic priests.[20] Gibault was a strict school, where punishment for even the smallest infraction included beatings with either a wooden paddle or a leather strap. Manson ran away from Gibault and slept in the woods, under bridges, and wherever else he could find shelter.[21]

Manson fled home to his mother, and spent Christmas 1947 in McMechen, at his aunt and uncle's house.[22] His mother returned him to Gibault. Ten months later, he ran away to Indianapolis.[23] In 1948, in Indianapolis, Manson committed his first known crime by robbing a grocery store. At first the robbery was simply to find something to eat. However, Manson found a cigar box containing just over a hundred dollars, and he took the money. He used the money to rent a room on Indianapolis's Skid Row and to buy food.[24]

For a time, Manson had a job delivering messages for Western Union in an attempt to live a life free of crime. However, he quickly began to supplement his wages through petty theft.[21] He was eventually caught, and in 1949 a sympathetic judge sent him to Boys Town, a juvenile facility in Omaha, Nebraska.[25] After four days at Boys Town, he and fellow student Blackie Nielson obtained a gun and stole a car. They used it to commit two armed robberies on their way to the home of Nielson's uncle in Peoria, Illinois.[26][27] Nielson's uncle was a professional thief, and when the boys arrived he allegedly took them on as apprentices.[20] Manson was arrested two weeks later during a nighttime raid on a Peoria store. In the investigation that followed, he was linked to his two earlier armed robberies. He was sent to the Indiana Boys School, a strict reform school.[28]

At the school, other students allegedly raped Manson with the encouragement of a staff member, and he was repeatedly beaten. He ran away from the school eighteen times.[25] While at the school, Manson developed a self-defense technique he later called the "insane game". When he was physically unable to defend himself, he would screech, grimace and wave his arms to convince aggressors that he was insane. After a number of failed attempts, he escaped with two other boys in February 1951.[29][27] The three escapees were robbing filling stations while attempting to drive to California in stolen cars when they were arrested in Utah. For the federal crime of driving a stolen car across state lines, Manson was sent to Washington, D.C.'s National Training School for Boys.[30] On arrival he was given aptitude tests which determined that he was illiterate, but had an above-average IQ of 109. His case worker deemed him aggressively antisocial.[29][27]

First imprisonment

On a psychiatrist's recommendation, Manson was transferred in October 1951 to Natural Bridge Honor Camp, a minimum security institution.[27] His aunt visited him and told administrators she would let him stay at her house and would help him find work. Manson had a parole hearing scheduled for February 1952. However, in January, he was caught raping a boy at knifepoint. Manson was transferred to the Federal Reformatory in Petersburg, Virginia. There he committed a further "eight serious disciplinary offenses, three involving homosexual acts". He was then moved to a maximum security reformatory at Chillicothe, Ohio, where he was expected to remain until his release on his 21st birthday in November 1955. Good behavior led to an early release in May 1954, to live with his aunt and uncle in McMechen.[31]

In January 1955, Manson married a hospital waitress named Rosalie Jean Willis.[32][page needed] Around October, about three months after he and his pregnant wife arrived in Los Angeles in a car he had stolen in Ohio, Manson was again charged with a federal crime for taking the vehicle across state lines. After a psychiatric evaluation, he was given five years' probation. Manson's failure to appear at a Los Angeles hearing on an identical charge filed in Florida resulted in his March 1956 arrest in Indianapolis. His probation was revoked, and he was sentenced to three years' imprisonment at Terminal Island in Los Angeles.[27]

While Manson was in prison, Rosalie gave birth to their son, Charles Manson Jr. During his first year at Terminal Island, Manson received visits from Rosalie and his mother, who were now living together in Los Angeles. In March 1957, when the visits from his wife ceased, his mother informed him Rosalie was living with another man. Less than two weeks before a scheduled parole hearing, Manson tried to escape by stealing a car. He was given five years' probation and his parole was denied.[27]

Second imprisonment

Manson received five years' parole in September 1958, the same year in which Rosalie received a decree of divorce. By November, he was pimping a 16-year-old girl and was receiving additional support from a girl with wealthy parents. In September 1959, he pleaded guilty to a charge of attempting to cash a forged U.S. Treasury check, which he claimed to have stolen from a mailbox; the latter charge was later dropped. He received a 10-year suspended sentence and probation after a young woman named Leona, who had an arrest record for prostitution, made a "tearful plea" before the court that she and Manson were "deeply in love ... and would marry if Charlie were freed".[27] Before the year's end, the woman did marry Manson, possibly so she would not be required to testify against him.[27]

Manson took Leona and another woman to New Mexico for purposes of prostitution, resulting in him being held and questioned for violating the Mann Act. Though he was released, Manson correctly suspected that the investigation had not ended. When he disappeared in violation of his probation, a bench warrant was issued. An indictment for violation of the Mann Act followed in April 1960.[27] Following the arrest of one of the women for prostitution, Manson was arrested in June in Laredo, Texas, and was returned to Los Angeles. For violating his probation on the check-cashing charge, he was ordered to serve his ten-year sentence.[27]

Manson spent a year trying unsuccessfully to appeal the revocation of his probation. In July 1961, he was transferred from the Los Angeles County Jail to the United States Penitentiary at McNeil Island, Washington. There, he took guitar lessons from Barker–Karpis gang leader Alvin "Creepy" Karpis, and obtained from another inmate a contact name of someone at Universal Studios in Hollywood, Phil Kaufman.[33] Among his fellow prisoners during this time was Danny Trejo, who participated in several hypnosis sessions.[34] According to Jeff Guinn's 2013 biography of Manson, his mother moved to Washington State to be closer to him during his McNeil Island incarceration, working nearby as a waitress.[35]

Although the Mann Act charge had been dropped, the attempt to cash the Treasury check was still a federal offense. Manson's September 1961 annual review noted he had a "tremendous drive to call attention to himself", an observation echoed in September 1964.[27] In 1963, Leona was granted a divorce. During the process she alleged that she and Manson had a son, Charles Luther.[27] According to a popular urban legend, Manson auditioned unsuccessfully for the Monkees in late 1965; this is refuted by the fact that Manson was still incarcerated at McNeil Island at that time.[36]

In June 1966, Manson was sent for the second time to Terminal Island in preparation for early release. By the time of his release day on March 21, 1967, he had spent more than half of his 32 years in prisons and other institutions. This was mainly because he had broken federal laws. Federal sentences were, and remain, much more severe than state sentences for many of the same offenses. Telling the authorities that prison had become his home, he requested permission to stay.[27]

1968: San Francisco and cult formation

Parolee and patient

Less than a month after his 1967 release from prison, Manson moved to Berkeley from Los Angeles,[37] which could have been a probation violation. Instead, after calling the San Francisco probation office upon his arrival, he was transferred to the supervision of criminology doctoral researcher and federal probation officer Roger Smith.[38] Until the spring of 1968, Smith worked at the Haight Ashbury Free Medical Clinic (HAFMC), which Manson and his family frequented throughout their stay in the Haight.[39] Roger Smith, as well as the HAFMC's founder David E. Smith, received funding from the National Institutes of Health, and reportedly the CIA[40][page needed] to study the effects of drugs like LSD and methamphetamine on the counterculture movement in Haight–Ashbury.[41] The patients at the clinic became subjects of their research, including Manson and his expanding group of (mostly) female followers, who came to see Roger Smith regularly.[42]

Manson received permission from Roger Smith to move from Berkeley to the Haight-Ashbury District in San Francisco. He first took LSD and would use it frequently during his time there.[37] David Smith, who had studied the effects of LSD and amphetamines in rodents,[43] wrote that the change in Manson's personality during this time "was the most abrupt Roger Smith had observed in his entire professional career."[44] Manson also read the book Stranger in a Strange Land, a science fiction novel by Robert A. Heinlein.[45] Inspired by the burgeoning free love philosophy in Haight–Ashbury during the Summer of Love, Manson began preaching his own philosophy based on a mixture of Stranger in a Strange Land, the Bible, Scientology, Dale Carnegie and the Beatles, which quickly earned him a following.[46]

Cult formation

Manson had already gained his first follower at the UC Berkeley campus, librarian Mary Brunner. He talked her into letting him sleep at her house for a few nights, an arrangement that quickly became permanent.[47] He then met Lynette "Squeaky" Fromme, a runaway teen, and convinced her to live with him and Brunner.[48][49] Manson soon began to attract large crowds of listeners and some dedicated followers.[50] He targeted individuals for manipulation who were emotionally insecure and social outcasts.[51] In his book Love Needs Care about his time at the HAFMC, David Smith claims that Manson attempted to reprogram their minds to "submit totally to his will" through the use of "LSD and … unconventional sexual practices" that would turn his followers into "empty vessels that would accept anything he poured."[51] Manson Family member Paul Watkins, testified that Manson would encourage group LSD trips and take lower doses himself to "keep his wits about him."[52] Watkins said that "Charlie's trip was to program us all to submit."[53] By the end of his stay in the Haight in April 1968, Manson had attracted 20 or so followers, all under the supervision of his parole officer Roger Smith and many of the staff at the HAFMC.[54]

The core members of Manson's following eventually included: Charles 'Tex' Watson, a musician and former actor; Bobby Beausoleil, a former musician and pornographic actor; Brunner; Susan Atkins; Patricia Krenwinkel; and Leslie Van Houten.[55][56][57]

Further arrests

Supervised by his parole officer Roger Smith, Manson grew his family through drug use and prostitution[54] without interference from the authorities. Manson was arrested on July 31, 1967, for attempting to prevent the arrest of one of his followers, Ruth Ann Moorehouse. Instead of Manson being sent back to prison, the charge was reduced to a misdemeanor and Manson was given three additional years of probation.[58] He avoided prosecution again in July 1968, when he and the family were arrested while moving from San Francisco to Los Angeles with the permission of Roger Smith,[59] when his bus crashed into a ditch, where Manson and members of his family, including Brunner and Manson's newborn baby, were found sleeping naked by police.[60] Afterwards, he was again arrested and released only a few days later, this time on a drug charge.[61][58]

Doomsday beliefs

The Manson Family developed into a doomsday cult when Manson became fixated on the idea of an imminent apocalyptic race war between America's Black population and the larger White population. A white supremacist,[62][63] Manson told some of the Manson Family that Black people in America would rise up and kill all white people except for Manson and his "Family", but that they were not intelligent enough to survive on their own; they would need a white man to lead them, and so they would serve Manson as their "master".[64][65] According to Vincent Bugliosi, in late 1968, Manson adopted the term "Helter Skelter", taken from a song on the Beatles' recently released White Album, to refer to this upcoming war.[66]

1969–1971: Murders and trial

Murders

In early August 1969, some Manson Family members committed murders in Los Angeles. The Manson Family gained national notoriety after the murder of actress Sharon Tate and four others in her home on August 8 and 9, 1969,[67] and Leno and Rosemary LaBianca the next day. Tex Watson and three other members of the Family committed the Tate–LaBianca murders, allegedly under Manson's instructions.[68][69] While it was later accepted at trial that Manson never expressly ordered the murders, his behavior was deemed to warrant a conviction of first degree murder and conspiracy to commit murder. Evidence pointed to Manson's obsession with inciting a race war by killing those he thought were "pigs" and his belief that this would show the "nigger" how to do the same.[1] Family members were also responsible for other assaults, thefts, crimes, and the attempted assassination of President Gerald Ford in Sacramento by Lynette "Squeaky" Fromme.[70]

While it is often thought that Manson never murdered or attempted to murder anyone himself, true crime writer James Buddy Day, in his book Hippie Cult Leader: The Last Words of Charles Manson, claimed that Manson shot drug dealer Bernard Crowe on July 1, 1969.[71] Crowe survived.[72]

Trial

The State of California tried Manson for the Tate and LaBianca murders with co-defendants, Leslie Van Houten, Susan Atkins, and Patricia Krenwinkel. Co-defendant Tex Watson was tried at a later date after being extradited from Texas.[73] The trial began on July 15, 1970. Manson appeared wearing fringed buckskins, his typical clothing at Spahn Ranch.[74]

On July 24, 1970 – the first day of testimony – Manson appeared in court with an "X" carved into his forehead. His followers issued a statement from Manson saying "I have "X'd myself from your world".[75] The following day, Manson's co-defendants, Van Houten, Atkins, and Krenwinkel, also appeared in court, with an "X" carved in their foreheads.[76][77]

Members of the Manson Family camped outside of the courthouse, and held a vigil on a street corner, because they were excluded from the courtroom for being disruptive. Other members of the Manson Family also carved crosses into their heads.[75] One day some members of the Manson Family wore saffron robes to the trial, saying if Manson was convicted they would immolate themselves – a reference to monks and nuns in Vietnam who set fire to themselves to protest the Vietnam war.[74]

The State presented dozens of witnesses during the trial. However, its primary witness was Linda Kasabian, who was present during the Tate murders on August 8–9, 1969. Kasabian provided graphic testimony of the Tate murders, which she observed from outside the house. She was also in the car with Manson on the following evening, when, according to her testimony, he ordered the LaBianca killings. Kasabian spent days on the witness stand, being cross-examined by the defendants' lawyers. After testifying, Kasabian went into hiding for the next forty years.[11][page needed]

In early August 1970, President Richard Nixon told reporters that he believed that Manson was guilty of the murders, "either directly or indirectly".[78] Manson obtained a copy of the newspaper and held up the headline to the jury.[11][page needed] The defendants' attorneys then called for a mistrial, arguing that their clients had allegedly killed far fewer people than "Nixon's war machine in Vietnam".[78] Judge Charles H. Older polled each member of the jury, to determine whether each juror saw the headline and whether it affected his or her ability to make an independent decision. All of the jurors affirmed that they could still decide independently.[11][page needed] Shortly after, the female defendants – Atkins, Krenwinkel and Van Houten – were removed from the room for chanting, "Nixon says we are guilty. So why go on?"[11][page needed]

On October 5, 1970, Manson attempted to attack Judge Older while the jury was present in the room. Manson first threatened Older, and then jumped over his lawyer's table with a sharpened pencil, in the direction of Older. Manson was restrained before reaching the judge. While being led out of the courtroom, Manson screamed at Older, "In the name of Christian justice, someone should cut your head off!" Meanwhile, the female defendants began chanting something in Latin. Judge Older began wearing a .38 caliber pistol to the trial afterwards.[79]

On November 16, 1970, the State of California rested its case after presenting twenty-two weeks worth of evidence. The defendants then stunned the courtroom by announcing that they had no witnesses to present, and rested their case.[80]

Manson's testimony

Immediately after defendants' counsel rested their case, the three female defendants shouted that they wanted to testify. Their attorneys advised the court, in chambers, that they opposed their clients testifying. Apparently, the female defendants wanted to testify that Manson had had nothing to do with the murders.[81]

The following day, Manson himself announced that he too wanted to testify. The judge allowed Manson to testify outside the presence of the jury. He stated as follows:

These children that come at you with knives, they are your children. You taught them. I didn't teach them. I just tried to help them stand up. Most of the people at the ranch that you call the Family were just people that you did not want.[81]

Manson continued, equating his actions to those of society at large:

I know this: that in your hearts and your souls, you are as much responsible for the Vietnam war as I am for killing these people. ... I can't judge any of you. I have no malice against you and no ribbons for you. But I think that it is high time that you all start looking at yourselves, and judging the lie that you live in.[82]

Manson concluded, claiming that he too was a creation of a system that he viewed as fundamentally violent and unjust:

My father is the jailhouse. My father is your system. ... I am only what you made me. I am only a reflection of you. ... You want to kill me? Ha! I am already dead – have been all my life. I've spent twenty-three years in tombs that you have built.[82]

After Manson finished speaking, Judge Older offered to let him testify before the jury. Manson replied that it was not necessary. Manson then told the female defendants that they no longer needed to testify.[83]

On November 30, 1970, Leslie Van Houten's attorney, Ronald Hughes, failed to appear for the closing arguments in the trial.[83] He was later found dead in a California state park. His body was badly decomposed, and it was impossible to tell the cause of death. Hughes had disagreed with Manson during the trial, taking the position that his client, Van Houten, should not testify to claim that Manson had no involvement with the murders. Some have alleged that Hughes was murdered by the Manson Family.[84]

On January 25, 1971, the jury found Manson, Krenwinkel and Atkins guilty of first degree murder in all seven of the Tate and LaBianca killings. The jury found Van Houten guilty of murder in the first degree in the LaBianca killings.[85]

Sentencing

After the convictions, the court held a separate hearing before the same jury to determine if the defendants should receive the death sentence.

Each of the three female defendants – Atkins, Van Houten, and Krenwinkel – took the stand. They provided graphic details of the murders and testified that Manson was not involved. According to the female defendants, they had committed the crimes in order to help fellow Manson Family member Bobby Beausoleil get out of jail, where he was being held for the murder of Gary Hinman. The female defendants testified that the Tate-LaBianca murders were intended to be copycat crimes, similar to the Hinman killing. Atkins, Krenwinkel and Van Houten claimed they did this under the direction of the state's prime witness, Linda Kasabian. The defendants did not express remorse for the killings.[86]

On March 4, 1971, during the sentencing hearings, Manson trimmed his beard to a fork and shaved his head, telling the media, "I am the Devil, and the Devil always has a bald head!" However, the female defendants did not immediately shave their own heads. The state prosecutor, Vincent Bugliosi, later speculated in his book, Helter Skelter, that they refrained from doing so, in order to not appear to be completely controlled by Manson (as they had when they each carved an "X" in their foreheads, earlier in the trial).[87]

On March 29, 1971, the jury sentenced all four defendants to death. When the female defendants were led into the courtroom, each of them had shaved their heads, as had Manson. After hearing the sentence, Atkins shouted to the jury, "Better lock your doors and watch your kids."[88]

The Manson murder trial was the longest murder trial in American history when it occurred, lasting nine and a half months. The trial was among the most publicized American criminal cases of the twentieth century and was dubbed the "trial of the century". The jury had been sequestered for 225 days, longer than any jury before it. The trial transcript alone ran to 209 volumes or 31,716 pages.[88]

1971–2017: Third imprisonment

Post-trial events

Manson was admitted to state prison from Los Angeles County on April 22, 1971, for seven counts of first-degree murder and one count of conspiracy to commit murder for the deaths of Abigail Ann Folger, Wojciech Frykowski, Steven Earl Parent, Sharon Tate Polanski, Jay Sebring, and Leno and Rosemary LaBianca. As the death penalty was ruled unconstitutional in 1972, Manson was re-sentenced to life with the possibility of parole. His initial death sentence was modified to life on February 2, 1977.

On December 13, 1971, Manson was convicted of first-degree murder in Los Angeles County Court for the July 25, 1969, death of musician Gary Hinman. He was also convicted of first-degree murder for the August 1969 death of Donald Jerome "Shorty" Shea. Following the 1972 decision of California v. Anderson, California's death sentences were ruled unconstitutional and that "any prisoner now under a sentence of death ... may file a petition for writ of habeas corpus in the superior court inviting that court to modify its judgment to provide for the appropriate alternative punishment of life imprisonment or life imprisonment without possibility of parole specified by statute for the crime for which he was sentenced to death."[89] Manson was thus eligible to apply for parole after seven years' incarceration.[90] His first parole hearing took place on November 16, 1978, at California Medical Facility in Vacaville, where his petition was rejected.[91][92]

1980s–1990s

In the 1980s, Manson gave four interviews to the mainstream media. The first, recorded at California Medical Facility and aired on June 13, 1981, was by Tom Snyder for NBC's The Tomorrow Show. The second, recorded at San Quentin State Prison and aired on March 7, 1986, was by Charlie Rose for CBS News Nightwatch, and it won the national news Emmy Award for Best Interview in 1987.[93] The third, with Geraldo Rivera in 1988, was part of the journalist's prime-time special on Satanism.[94] At least as early as the Snyder interview, Manson's forehead bore a swastika in the spot where the X carved during his trial had been.[95]

Nikolas Schreck conducted an interview with Manson for his documentary Charles Manson Superstar (1989). Schreck concluded that Manson was not insane but merely acting that way out of frustration.[96][97]

On September 25, 1984, Manson was imprisoned in the California Medical Facility at Vacaville when inmate Jan Holmstrom poured paint thinner on him and set him on fire, causing second and third degree burns on over 20 percent of his body. Holmstrom explained that Manson had objected to his Hare Krishna chants and verbally threatened him.[91][failed verification]

After 1989, Manson was housed in the Protective Housing Unit at California State Prison, Corcoran, in Kings County. The unit housed inmates whose safety would be endangered by general-population housing. He had also been housed at San Quentin State Prison,[93] California Medical Facility in Vacaville,[91][failed verification] Folsom State Prison and Pelican Bay State Prison.[98][citation needed] In June 1997, a prison disciplinary committee found that Manson had been trafficking drugs.[98] He was moved from Corcoran State Prison to Pelican Bay State Prison a month later.[98]

2000s–2017

On September 5, 2007, MSNBC aired The Mind of Manson, a complete version of a 1987 interview at California's San Quentin State Prison. The footage of the "unshackled, unapologetic, and unruly" Manson had been considered "so unbelievable" that only seven minutes of it had originally been broadcast on Today, for which it had been recorded.[99]

In March 2009, a photograph of Manson showing a receding hairline, grizzled gray beard and hair, and the swastika tattoo still prominent on his forehead was released to the public by California corrections officials.[100]

In 2010, the Los Angeles Times reported that Manson was caught with a cell phone in 2009 and had contacted people in California, New Jersey, Florida and British Columbia. A spokesperson for the California Department of Corrections stated that it was not known if Manson had used the phone for criminal purposes.[101] Manson also recorded an album of acoustic pop songs with additional production by Henry Rollins, titled Completion. Only five copies were pressed: two belong to Rollins, while the other three are presumed to have been with Manson. The album remains unreleased.[102]

Illness and death

On January 1, 2017, Manson was being held at Corcoran Prison, when he was rushed to Mercy Hospital in downtown Bakersfield, because he had gastrointestinal bleeding. A source told the Los Angeles Times that Manson was very ill,[103] and TMZ reported that his doctors considered him "too weak" for surgery that normally would be performed in cases such as his.[104] He was returned to prison on January 6, and the nature of his treatment was not disclosed.[105] On November 15, 2017, an unauthorized source said that Manson had returned to a hospital in Bakersfield,[106] but the California Department of Corrections and Rehabilitation did not confirm this in conformity with state and federal medical privacy laws.[107] He died from cardiac arrest resulting from respiratory failure, brought on by colon cancer, at the hospital on November 19.[108][109][110]

Three people stated their intention to claim Manson's estate and body.[111][112][113] Manson's grandson Jason Freeman stated his intent to take possession of Manson's remains and personal effects.[114] Manson's pen-pal Michael Channels claimed to have a Manson will dated February 14, 2002, which left Manson's entire estate and Manson's body to Channels.[115][116] Manson's friend Ben Gurecki claimed to have a Manson will dated January 2017 which gives the estate and Manson's body to Matthew Roberts, another alleged son of Manson.[111][112] In 2012, CNN ran a DNA match to see if Freeman and Roberts were related to each other and found that they were not. According to CNN, two prior attempts to DNA match Roberts with genetic material from Manson failed, but the results were reportedly contaminated.[117] On March 12, 2018, the Kern County Superior Court in California decided in favor of Freeman in regard to Manson's body. Freeman had Manson cremated on March 20, 2018.[118] As of February 7, 2020, Channels and Freeman still had petitions to California courts attempting to establish the heir of Manson's estate. At that time, Channels was attempting to force Freeman to submit DNA to the court for testing.[119]

Personal life

Involvement with Scientology

Manson began studying Scientology while incarcerated with the help of fellow inmate Lanier Rayner, and in July 1961, Manson listed his religion as Scientology.[120] A September 1961 prison report argues that Manson "appears to have developed a certain amount of insight into his problems through his study of this discipline".[121] Upon his release in 1967, Manson traveled to Los Angeles where he reportedly "met local Scientologists and attended several parties for movie stars".[122][123][124] Manson completed 150 hours of auditing.[125] Manson's "right hand man", Bruce M. Davis, worked at the Church of Scientology headquarters in London from November 1968 to April 1969."[126]

Relationships and alleged child

In 2009, Los Angeles disc jockey Matthew Roberts released correspondence and other evidence indicating that he might be Manson's biological son. Roberts' biological mother claims that she was a member of the Manson Family who left in mid-1967 after being raped by Manson; she returned to her parents' home to complete the pregnancy, gave birth on March 22, 1968, and put Roberts up for adoption. CNN conducted a DNA test between Matthew Roberts and Manson's known biological grandson Jason Freeman in 2012, showing that Roberts and Freeman did not share DNA.[117] Roberts subsequently attempted to establish that Manson was his father through a direct DNA test which proved definitively that Roberts and Manson were not related.[127]

In 2014, the imprisoned Manson became engaged to 26-year-old Afton Elaine Burton and obtained a marriage license on November 7.[128] Manson gave Burton the nickname "Star". She had been visiting him in prison for at least nine years and maintained several websites that proclaimed his innocence.[129] The wedding license expired on February 5, 2015, without a marriage ceremony taking place.[130] Journalist Daniel Simone reported that the wedding was canceled after Manson discovered that Burton wanted to marry him only so that she and friend Craig Hammond could use his corpse as a tourist attraction after his death.[130][131] According to Simone, Manson believed that he would never die and may simply have used the possibility of marriage as a way to encourage Burton and Hammond to continue visiting him and bringing him gifts. Burton said on her website that the reason that the marriage did not take place was merely logistical. Manson had an infection and had been in a prison medical facility for two months and could not receive visitors. She said that she still hoped that the marriage license would be renewed and the marriage would take place.[130]

Psychology

On April 11, 2012, Manson was denied release at his 12th parole hearing, which he did not attend. After his March 27, 1997, parole hearing, Manson refused to attend any of his later hearings. The panel at that hearing noted that Manson had a "history of controlling behavior" and "mental health issues" including schizophrenia and paranoid delusional disorder, and was too great a danger to be released.[132] The panel also noted that Manson had received 108 rules violation reports, had no indication of remorse, no insight into the causative factors of the crimes, lacked understanding of the magnitude of the crimes, had an exceptional, callous disregard for human suffering and had no parole plans.[133] At the April 11, 2012, parole hearing, it was determined that Manson would not be reconsidered for parole for another 15 years, i.e. not before 2027, at which time he would have been 92 years old.[134]

Legacy

Cultural impact

In June 1970, Rolling Stone made Manson their cover story.[135] Bernardine Dohrn of the Weather Underground reportedly said of the Tate murders: "Dig it, first they killed those pigs, then they ate dinner in the same room with them, then they even shoved a fork into a victim's stomach. Wild!"[136] Manson fanatic James Mason claimed to be acting on a suggestion from Charles Manson based on his interpretation of something Manson said in a televised interview, when Mason founded the Universal Order, a neo-Nazi group that has influenced other movements such as the terrorist group the Atomwaffen Division.[137] Bugliosi quoted a BBC employee's assertion that a "neo-Manson cult" existed in Europe, represented by approximately 70 rock bands playing songs by Manson and "songs in support of him".[90]

Music

Manson was a struggling musician, seeking to make it big in Hollywood between 1967 and 1969. The Beach Boys did a cover of one of his songs. Other songs were publicly released only after the trial for the Tate murders started. On March 6, 1970, LIE, an album of Manson music, was released.[138][139][140][141] This included "Cease to Exist", a Manson composition the Beach Boys had recorded with modified lyrics and the title "Never Learn Not to Love".[142][143] Over the next couple of months only about 300 of the album's 2,000 copies sold.[144]

There have been several other releases of Manson recordings – both musical and spoken. One of these, The Family Jams, includes two compact discs of Manson's songs recorded by the Family in 1970, after Manson and the others had been arrested. Guitar and lead vocals are supplied by Steve Grogan;[145][failed verification] additional vocals are supplied by Lynette Fromme, Sandra Good, Catherine Share, and others.[citation needed] One Mind, an album of music, poetry, and spoken word, new at the time of its release, in April 2005, was put out under a Creative Commons license.[146][147]

American rock band Guns N' Roses recorded Manson's "Look at Your Game, Girl", included as an unlisted 13th track on their 1993 album "The Spaghetti Incident?"[90][failed verification][148][149] "My Monkey", which appears on Portrait of an American Family by the American rock band Marilyn Manson, includes the lyrics "I had a little monkey / I sent him to the country and I fed him on gingerbread / Along came a choo-choo / Knocked my monkey cuckoo / And now my monkey's dead." These lyrics are from Manson's "Mechanical Man",[150] which is heard on LIE. Crispin Glover covered "Never Say 'Never' to Always" on his album The Big Problem ≠ The Solution. The Solution=Let It Be released in 1989.

Musical performers such as Kasabian,[151] Spahn Ranch,[152] and Marilyn Manson[153] derived their names from Manson and his lore.

Documentaries

- 1973: Manson, directed by Robert Hendrickson and Laurence Merrick[154]

- 1989: Charles Manson Superstar, directed by Nikolas Schreck[155]

- 2014: Life After Manson, directed by Olivia Klaus[156]

- 2017: Manson: Inside the Mind of a Mad Man, television documentary about Reet Jurvetsen.

- 2017: Murder Made Me Famous, Charles Manson: What Happened?.[157]

- 2017: Inside the Manson Cult: The Lost Tapes[158]

- 2017: Charles Manson: The Final Words, narrated by Rob Zombie, focuses on the Manson Family murders told from Manson's perspective, directed by James Buddy Day.[159]

- 2018: Inside the Manson Cult: The Lost Tapes, narrated by Liev Schreiber, looks inside the Manson Family.[160][161]

- 2019: I Lived with a Killer: The Manson Family. Dianne Lake discusses what she witnessed of Manson's "peace-and-love hippie philosophy" as it became "dark, dangerous and evil".[162]

- 2019: Charles Manson: The Funeral, directed by James Buddy Day.[163]

- 2019: Manson: The Women, featuring Lynette "Squeaky" Fromme, Sandra "Blue" Good, Catherine "Gypsy" Share, and Diane "Snake" Lake, documentary special on Oxygen, directed by James Buddy Day.[164]

Fiction inspired by Manson

- 1976: Helter Skelter, a television drama.[165]

- 1984: Manson Family Movies, a film drama.[166]

- 1990: The Manson Family, a musical opera by John Moran.[167]

- 1990: Assassins, a Broadway musical with references to Manson.[168]

- 1992: The Ben Stiller Show, a sketch series with Manson as a recurring character portrayed by Bob Odenkirk.[169]

- 1998: "Merry Christmas, Charlie Manson!", an episode of South Park centered around Manson.[170]

- 2003: The Dead Circus, a novel that includes the activities of the Manson Family as a major plot point.[171]

- 2003: The Manson Family, a crime drama/horror film centered around the Manson Family.

- 2004: Helter Skelter, a crime film about the Manson Family and about Linda Kasabian.

- 2006: Live Freaky! Die Freaky!, a stop-motion animated film based on the murders.

- 2014: House of Manson, a biographical feature film focusing on the life of Charles Manson from his childhood to his arrest.

- 2015: Manson Family Vacation, an indie comedy inspired by Manson.[172]

- 2015–16: Aquarius, a television crime drama that includes storylines inspired by actual events which involved Manson.[173]

- 2016: The Girls, a novel by Emma Cline loosely inspired by the Manson Family.

- 2016: Wolves at the Door, a horror film directed by John R. Leonetti loosely based on the murder of Sharon Tate.

- 2017: Mindhunter; the first episode of season 1 used Manson as a case study. Manson is then featured in the second season.[174]

- 2017: American Horror Story: Cult, the seventh season of the horror anthology series American Horror Story.

- 2018: Charlie Says, a film centered around Manson and three of his followers.[175]

- 2019: The Haunting of Sharon Tate; directed by Daniel Farrands, the film revolves around Sharon Tate during the last evening of her life.

- 2019: Once Upon a Time in Hollywood; directed by Quentin Tarantino, the film has a plot revolving around Manson and the Manson Family.[176]

- 2019: Zeroville, a film that starts in the aftermath of the Sharon Tate murders in Los Angeles, with the main character suspected of being involved. Manson is portrayed by Scott Haze.[177]

See also

- ATWA, an acronym propounded by Manson and followers, for Air, Trees, Water, Animals and All The Way Alive

References

- Citations

- ^ a b "People v. Manson". Justia Law. Archived from the original on May 20, 2018. Retrieved May 11, 2019.

- ^ "Manson Murders Motive | Copycat Motive". www.cielodrive.com. Archived from the original on May 11, 2019. Retrieved May 11, 2019.

- ^ Day, James Buddy (Director). 2017. Charles Manson: The Final Words (Documentary). Pyramid Productions.

- ^ Woods, Jared (November 21, 2017). "15 Lesser-Known Facts About The Late Charles Manson". The Clever. Archived from the original on November 29, 2017. Retrieved November 22, 2017.

- ^ Kathleen Maddox; geni.com

- ^ Bugliosi & Gentry 1974, pp. 136–137.

- ^ Reitwiesner, William Addams. Provisional ancestry of Charles Manson Archived March 5, 2016, at the Wayback Machine; retrieved April 26, 2007.

- ^ "Internet Accuracy Project: Charles Manson". AccuracyProject.org. Archived from the original on February 24, 2021. Retrieved October 28, 2012.

- ^ Smith, Dave (January 26, 1971). "Mother Tells Life of Manson as Boy". Los Angeles Times.

- ^ Guinn 2013, p. 22.

- ^ a b c d e Bugliosi & Gentry 1974.

- ^ Guinn 2013, p. 23.

- ^ Guinn 2013, p. 27.

- ^ "Long Before Little Charlie Became the Face of Evil". The New York Times. August 7, 2013. Archived from the original on September 30, 2015. Retrieved January 7, 2016.

- ^ Guinn 2013, p. 36.

- ^ Guinn 2013, p. 38.

- ^ a b Lansing, H. Allegra (July 11, 2019). "Son of Man: The Early Life of Charles Manson". Medium. Boston, Massachusetts: A Medium Corporation. Archived from the original on February 28, 2022. Retrieved August 17, 2020.

- ^ Maslin, Janet (August 6, 2013). "Long Before Little Charlie Became the Face of Evil". The New York Times. New York City. Archived from the original on September 30, 2015. Retrieved August 17, 2020.

- ^ "Charles Manson – Diane Sawyer Documentary.

- ^ a b Guinn 2013, p. 43.

- ^ a b Hunter, Al (January 22, 2015). "Charles Manson – Hoosier Juvenile Dilenquent". The Weekly View.

- ^ Guinn 2013, pp. 37–42.

- ^ Mitchell, Dawn (January 14, 2014). "Retro Indy: Charles Manson, mass murderer and cult leader, spent time in Indiana". The Indianapolis Star. Archived from the original on September 19, 2020. Retrieved August 17, 2020.

- ^ Mercer, David (November 20, 2017). "Charles Manson's life and crimes: a timeline". Sky News. Archived from the original on October 24, 2020. Retrieved August 17, 2020.

- ^ a b Charles Manson – Diane Sawyer Interview.[clarification needed]

- ^ Guinn 2013, pp. 42–43.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m Bugliosi & Gentry 1974, pp. 136–146.

- ^ Ray, Richard (November 20, 2017). "In Indiana, Charles Manson Was Once a 'Lost Little Kid': Report". NBC Chicago. Archived from the original on October 25, 2020. Retrieved August 17, 2020.

- ^ a b Guinn 2013, p. 45.

- ^ Bugliosi & Gentry 1974, pp. 137–146.

- ^ Guinn 2013, p. 52.

- ^ Manson 1988.

- ^ "Short Bits 2 – Charles Manson and the Beach Boys". Lost in the Grooves. April 13, 2006. Archived from the original on July 18, 2012. Retrieved July 2, 2012.

- ^ "Danny Trejo Says Charles Manson Once Hypnotized Him in Jail". Mediaite. July 7, 2021. Archived from the original on July 7, 2021. Retrieved July 7, 2021.

- ^ Rule, Ann (August 18, 2013). "There Will Be Blood". The New York Times Book Review. p. 14.

- ^ "Did Charles Manson Audition for The Monkees?". snopes.com. Retrieved July 5, 2018.

- ^ a b Guinn 2013, p. 94

- ^ O'Neill 2019, p. 237.

- ^ Smith, David E; Luce, John (1971). Love Needs Care: A History of San Francisco's Haight-Ashbury Free Medical Clinic and Its Pioneer Role Treating Drug-abuse Problems. Boston, Little, Brown. Retrieved April 30, 2021. p. 52

- ^ O'Neill 2019.

- ^ O'Neill 2019, p. 251

- ^ O'Neill 2019, p. 266

- ^ O'Neill 2019, p. 260

- ^ Smith, p. 257

- ^ O'Neill 2019, p. 237

- ^ Guinn 2013, p. 95

- ^ Guinn 2013, p. 82

- ^ Guinn 2013, p. 97

- ^ Serratore, Angela (July 25, 2019). "The True Story of the Manson Family". Smithsonian Magazine. Washington, D.C. Archived from the original on August 18, 2020. Retrieved August 18, 2020.

- ^ Guinn 2013, p. 96

- ^ a b Smith, p. 259

- ^ Guinn 2013, p. 139

- ^ Melnick, Jeffrey Paul (2018). Creepy Crawling: Charles Manson and the Many Lives of America's Most Infamous Family. ISBN 978-1628728934. p. 16

- ^ a b Smith, p. 260

- ^ "Charles Manson's Son Says He Wishes He'd Gotten to Know Him Before His Death". insideedition.com. Inside Edition Inc, CBS Interactive. July 18, 2019. Archived from the original on August 24, 2019. Retrieved August 24, 2019.

- ^ Kovac, Adam. "We Spoke to Charles Manson's Guitarist About Making Art While Serving Time for Murder". Vice. New York City: Vice Media. Archived from the original on May 26, 2019. Retrieved August 24, 2019.

- ^ Milne, Andrew (July 6, 2019). "Meet Bobby Beausoleil: The Haight-Ashbury Hippie Who Became A Manson Family Murderer". allthatsinteresting.com. PBH Network. Archived from the original on August 24, 2019. Retrieved August 24, 2019.

- ^ a b O'Neill 2019, p. 242

- ^ O'Neill 2019, p. 244

- ^ O'Neill 2019, p. 246

- ^ O'Neill 2019, p. 248

- ^ Gill, Lauren (November 16, 2017). "Remember, Charles Manson Was a White Supremacist". Newsweek. Archived from the original on August 4, 2020. Retrieved August 17, 2020.

- ^ Thompson, Desire (November 20, 2017). "Charles Manson & His Obsession with Black People". Vibe. New York City. Archived from the original on August 13, 2020. Retrieved August 18, 2020.

- ^ Whitehead, John W. (August 3, 2010). "Helter Skelter: Racism and Murder". HuffPost. Archived from the original on October 30, 2020. Retrieved August 17, 2020.

- ^ Beckerman, Jim (August 9, 2019). "Charles Manson: 50 years later, murders have racist link to recent mass-killings". The Record. Archived from the original on January 24, 2021. Retrieved August 17, 2020.

- ^ Bugliosi & Gentry 1974, pp. 244.

- ^ Renee, Alexa (November 2, 2017). "The Manson family: Who are they and where are they now?". KXTV. Archived from the original on March 31, 2017. Retrieved November 5, 2017.

- ^ Lawrence, Jonelle (June 14, 2015). "Manson Family murders: Key players in the Tate-LaBianca killings". ABC7. Archived from the original on June 17, 2015. Retrieved November 5, 2017.

- ^ Hamilton, Matt (April 15, 2016). "Manson follower's chilling murder description: 'We started stabbing and cutting up the lady'". Los Angeles Times. Archived from the original on October 8, 2021. Retrieved October 8, 2021.

- ^ Schmidt, Dick (September 5, 2017). "'Pure luck' led to famous photo of would-be President Ford assassin". The Sacramento Bee. Archived from the original on September 5, 2017. Retrieved November 5, 2017.

- ^ Waxman, Olivia B. (July 26, 2019). "Why Did the Manson Family Kill Sharon Tate? Here's the Story Charles Manson Told the Last Man Who Interviewed Him". Time. Archived from the original on September 24, 2020. Retrieved August 17, 2020.

- ^ Bugliosi & Gentry 1974, pp. 91–96, 99–113.

- ^ "Judge allows tapes to be released to LAPD in probe into possible unsolved Manson murders". Fox News. New York City: News Corp. March 27, 2013. Archived from the original on May 7, 2021. Retrieved August 17, 2020.

- ^ a b Linda Deutch, "'This is crazy': Former AP reporter remembers Manson trial", AP, November 20, 2017.

- ^ a b La Ganga, Maria L.; Himmelsbach-Weinstein, Erik (July 28, 2019). "Charles Manson's murderous imprint on L.A. endures as other killers have come and gone". Los Angeles Times. Archived from the original on November 1, 2019. Retrieved November 1, 2019.

- ^ Hawkins, Erik; Hilburn, Jair (August 6, 2019). "Manson And His Family Carved 'X' Into Their Foreheads During Wild Trial". Oxygen. Archived from the original on September 27, 2020. Retrieved August 17, 2020.

- ^ "Manson Ejected From Cortroom". The New York Times. January 29, 1971. Archived from the original on May 7, 2021. Retrieved August 17, 2020.

- ^ a b Rosenwald, Michael S. (August 8, 2019). "How Charles Manson almost won a mistrial, courtesy of Richard Nixon". The Washington Post. Archived from the original on July 26, 2020. Retrieved August 17, 2020.

- ^ Bugliosi & Gentry 1974, pp. 485–487.

- ^ Bugliosi & Gentry 1974, pp. 503–504.

- ^ a b Bugliosi & Gentry 1974, p. 507.

- ^ a b Bugliosi & Gentry 1974, pp. 509–510.

- ^ a b Bugliosi & Gentry 1974, p. 514.

- ^ Bugliosi & Gentry 1974, p. 595.

- ^ Bugliosi & Gentry 1974, pp. 537–539.

- ^ Bugliosi & Gentry 1974, pp. 560–564.

- ^ Bugliosi & Gentry 1974, pp. 571–572.

- ^ a b Bugliosi & Gentry 1974, pp. 592–594.

- ^ People v. Anderson Archived October 9, 2007, at the Wayback Machine, 493 P.2d 880, 6 Cal. 3d 628 (Cal. 1972), footnote (45) to final sentence of majority opinion. Retrieved April 7, 2008.

- ^ a b c Bugliosi & Gentry 1974, pp. 488–491.

- ^ a b c Bugliosi & Gentry 1974, pp. 497–498.

- ^ "Charles Manson Family and Sharon Tate-Labianca Murders – Cielodrive.com". Archived from the original on May 1, 2012. Retrieved April 24, 2012.

- ^ a b Joynt, Carol. Diary of a Mad Saloon Owner Archived July 14, 2011, at the Wayback Machine. April–May 2005.

- ^ Shales, Tom (October 31, 1988). "Rivera's 'Devil Worship' was TV at its Worst". San Jose Mercury News.

- ^ Itzkoff, Dave (July 31, 2007). "Hearts and Souls Dissected, in 12 Minutes or Less". The New York Times. Archived from the original on January 11, 2012. Retrieved October 31, 2009.

Appraisal of Tom Snyder, upon his death. Includes photograph of Manson with swastika on forehead during 1981 interview.

- ^ Charles Manson Superstar. 1989.

- ^ Interview with Nikolas Schreck. Interano Radio. August 1988.

- ^ a b c "Manson moved to a tougher prison after drug charge". Sun Journal. Lewiston, Maine. AP. August 22, 1997. p. 7A. Archived from the original on May 7, 2021. Retrieved January 16, 2013.

- ^ Transcript, MSNBC Live Archived December 11, 2019, at the Wayback Machine . September 5, 2007. Retrieved November 21, 2007.

- ^ "New prison photo of Charles Manson released". CNN. March 20, 2009. Archived from the original on July 29, 2009. Retrieved July 21, 2009.

- ^ Wilson, Greg (December 3, 2010). "'Cell' Phone: Charles Manson Busted with a Mobile". NBC Los Angeles. Archived from the original on October 19, 2012. Retrieved October 28, 2012.

- ^ Michaels, Sean (December 15, 2010). "Henry Rollins produced Charles Manson album". The Guardian. Archived from the original on October 29, 2017.

- ^ Winton, Richard; Hamilton, Matt; Branson-Potts, Hailey (January 4, 2017). "Killer Charles Manson's failing health renews focus on cult murder saga". Los Angeles Times. Archived from the original on January 5, 2017. Retrieved January 4, 2017.

- ^ "US killer Manson 'too weak' for surgery". RTÉ. January 7, 2017. Archived from the original on January 8, 2017. Retrieved January 7, 2017.

- ^ Winton, Richard; Christensen, Kim (January 7, 2017). "Charles Manson is returned to prison after stay at Bakersfield hospital". Los Angeles Times. Archived from the original on January 7, 2017. Retrieved January 7, 2017.

- ^ Tchekmedyian, Alene (November 15, 2017). "Charles Manson hospitalized in Bakersfield; severity of illness unclear". Los Angeles Times. Archived from the original on October 8, 2021. Retrieved October 8, 2021.

- ^ "Charles Manson's condition still unannounced". ABC 15. Scripps National Desk. November 17, 2017. Archived from the original on November 18, 2017. Retrieved November 18, 2017.

- ^ "Charles Manson Dead at 83". Rolling Stone. Archived from the original on November 20, 2017.

- ^ "Charles Manson Dead at 83". TMZ. November 19, 2017. Archived from the original on November 20, 2017. Retrieved February 21, 2020.

- ^ "Inmate Charles Manson Dies of Natural Causes". California Department of Corrections and Rehabilitation. November 19, 2017. Archived from the original on November 20, 2017. Retrieved November 20, 2017.

- ^ a b Dillon, Nancy (November 24, 2017). "Battle erupts over control of Charles Manson's remains, estate". New York Daily News. Archived from the original on November 27, 2017.

- ^ a b Feldman, Kate (November 28, 2017). "Charles Manson's secret prison pen pal Michael Channels wants murderer's body". New York Daily News. Archived from the original on December 5, 2017.

- ^ Perez, Chris (November 28, 2017). "Manson's pen pal files will and testament to get his body". New York Post. Archived from the original on December 5, 2017.

- ^ Rubenstein, Steve (November 21, 2017). "Manson's grandson hopes to claim remains, bring them to Florida". San Francisco Chronicle. Archived from the original on November 22, 2017. Retrieved November 22, 2017.

- ^ "Charles Manson Will Surfaces Pen Pal Gets Everything". TMZ.com. November 24, 2017. Archived from the original on November 26, 2017. Retrieved February 21, 2020.

- ^ "Charles Manson's Pen Pal, Grandson Battle For His Body". TMZ.com. November 29, 2017. Archived from the original on November 29, 2017. Retrieved February 21, 2020.

- ^ a b Marquez, Miguel (April 24, 2012). "Two men relate to same haunting specter – Charles Manson". CNN. Archived from the original on May 14, 2019. Retrieved May 14, 2019.

- ^ Melley, Brian (March 12, 2018). "Grandson wins bizarre battle over body of Charles Manson". The Washington Post. AP. Archived from the original on March 13, 2018. Retrieved March 12, 2018.

- ^ City News Service (February 7, 2020). "Man Who Claims He's Infamous Criminal's Grandson Appeals DNA Order". Archived from the original on February 18, 2020. Retrieved February 18, 2020.

- ^ Bugliosi & Gentry 1974, p. 260.

- ^ Bugliosi & Gentry 1974, p. 144.

- ^ Mallia, Joseph (March 5, 1998). "Inside the Church of Scientology – Church wields celebrity clout". Boston Herald. p. 30.

- ^ Roberts, Steven V. (December 7, 1969). "Charlie Manson, Nomadic Guru, Flirted With Crime in a Turbulent Childhood". The New York Times. p. 84.

- ^ Goodsell, Greg (February 23, 2010). "Manson once proclaimed Scientology". Catholic Online. www.catholic.org. Archived from the original on February 27, 2010. Retrieved February 24, 2010.

- ^ Cooper, Paulette. "The Scandal Behind the "Scandal of Scientology"". www.cs.cmu.edu. Archived from the original on November 12, 2019. Retrieved November 8, 2019.

- ^ Sanders 2002.

- ^ Briquelet, Kate (March 8, 2018). "The Battle Over Charles Manson's Corpse". Daily Beast. Archived from the original on June 26, 2019. Retrieved May 14, 2019.

- ^ 5 Things to Know About the 26-Year-Old Woman Charles Manson Might Marry Archived January 6, 2015, at the Wayback Machine Time. Retrieved January 5, 2015.

- ^ Deutsch, Linda. "Charles Manson Gets Marriage License". ABC News. Associated Press. Archived from the original on November 17, 2014. Retrieved November 17, 2014.

- ^ a b c Sanderson, Bill (February 8, 2015). "Charles Manson's fiancee wanted to marry him for his corpse: Source". The New York Post. Archived from the original on February 8, 2015. Retrieved February 2, 2015.

- ^ Hooton, Christopher (February 9, 2015). "Charles Manson wedding off after it emerges that fiancee Afton Elaine Burton 'just wanted his corpse for display'". The Independent. Archived from the original on February 10, 2015. Retrieved February 11, 2015.

- ^ "Charles Manson Quickly Denied Parole". Los Angeles Times. April 11, 2012. Archived from the original on April 11, 2012. Retrieved April 11, 2012.

- ^ "Parole Hearing: Charles Manson 2012". cielodrive.com. Archived from the original on August 7, 2017. Retrieved November 4, 2017.

- ^ Jones, Kiki (April 11, 2012). "Murderer Charles Manson Denied Parole – Central Coast News KION/KCBA". Kionrightnow.com. Archived from the original on April 13, 2012. Retrieved August 19, 2012."Mass murderer Charles Manson denied parole". April 11, 2012. Archived from the original on November 18, 2015. Retrieved November 18, 2015.

- ^ "Charles Manson: The Incredible Story of the Most Dangerous Man Alive". Rolling Stone. August 8, 2017. Archived from the original on August 8, 2017. Retrieved May 30, 2015.

- ^ "The Seeds of Terror". The New York Times. November 22, 1981. p. 5. Archived from the original on March 9, 2014. Retrieved February 2, 2014.

- ^ Lusher, Adam (November 20, 2017). "Charles Manson: Neo-Nazis hail serial killer a visionary and try to resurrect fascist movement created on his orders". The Independent. London, United Kingdom. Archived from the original on December 22, 2021. Retrieved February 28, 2022.

- ^ Bugliosi & Gentry 1974, p. 258-269.

- ^ Sanders 2002, p. 336.

- ^ Lie: The Love And Terror Cult Archived February 28, 2008, at the Wayback Machine. ASIN: B000005X1J. Amazon.com. Access date: November 23, 2007.

- ^ Syndicated column re LIE release Mike Jahn, August 1970.

- ^ Sanders 2002, pp. 64–65.

- ^ Dennis Wilson interview Archived December 15, 2007, at the Wayback Machine Circus magazine, October 26, 1976. Retrieved December 1, 2007.

- ^ Rolling Stone story on Manson, June 1970: "Coverwall – Rolling Stone". Rolling Stone. Archived from the original on December 23, 2016. Retrieved August 25, 2017.

- ^ Bugliosi & Gentry 1974, pp. 125–127.

- ^ Charles Manson Issues Album under Creative Commons Archived July 10, 2009, at the Wayback Machine pcmag.com. Retrieved April 14, 2008.

- ^ Yes it's CC! Archived December 27, 2008, at the Wayback Machine Photo verifying Creative Commons license of One Mind. blog.limewire.com. Retrieved April 13, 2008.

- ^ Review of The Spaghetti Incident? allmusic.com. Retrieved November 23, 2007.

- ^ Guns N' Roses Biography Archived January 13, 2017, at the Wayback Machine themusichype.com. Retrieved January 11, 2017.

- ^ Lyrics of "Mechanical Man" "Charles Manson – Mechanical Man Lyrics". Archived from the original on November 18, 2015. Retrieved November 18, 2015.

- ^ Maclean, Graeme. "Ukula Music :: speaking with Kasabian on their first trip to America". Ukula. Archived from the original on March 10, 2007. Retrieved August 8, 2013.

- ^ "Charles Manson's musical connections". NME. November 20, 2017. Archived from the original on November 21, 2017. Retrieved November 22, 2017.

- ^ Manson, Marilyn (1998). The Long Hard Road out of Hell. HarperCollins. pp. 85–87. ISBN 0-06-098746-4.

- ^ "Watch This Chilling Manson Documentary from 1973". vice.com. November 20, 2017. Archived from the original on July 5, 2018. Retrieved July 5, 2018.

- ^ Zagami, Leo Lyon (December 6, 2018). Confessions of an Illuminati, VOLUME II: The Time of Revelation and Tribulation Leading Up to 2020. ISBN 978-1-888729-62-7. Archived from the original on November 3, 2020. Retrieved January 19, 2019.

- ^ Klaus, Olivia (August 4, 2014). "My Life After Manson". The New York Times. Archived from the original on July 6, 2018. Retrieved July 5, 2018.

- ^ "Charles Manson". REELZ TV. November 4, 2017. Archived from the original on February 3, 2019. Retrieved February 3, 2019.

- ^ Turchiano, Danielle (August 27, 2018). "Fox Reveals First Look at 'Inside The Manson Cult: The Lost Tapes'". Variety. Archived from the original on November 18, 2018. Retrieved November 18, 2018.

- ^ "Charles Manson: The Final Words". REELZ TV. September 10, 2017. Archived from the original on January 28, 2019. Retrieved January 27, 2019.

- ^ Yuko, Elizabeth (September 17, 2018). "New Manson Doc Goes Inside Spahn Ranch". Rolling Stone. Archived from the original on March 22, 2019. Retrieved August 17, 2019.

- ^ Sergent, Jean (July 28, 2019). "Review: Manson – The Lost Tapes, the story of America's first family of darkness". The Spinoff. Archived from the original on August 10, 2019. Retrieved August 17, 2019.

- ^ "The Manson Family". REELZ TV. February 2, 2019. Archived from the original on February 3, 2019. Retrieved February 3, 2019.

- ^ Nolasco, Stephanie (April 12, 2019). "Man who says he's Charles Manson's grandson films infamous cult leader's funeral for doc: 'This is my story'". Fox News. Archived from the original on May 14, 2019. Retrieved May 14, 2019.

- ^ Kilkenny, Katie (August 10, 2019). "Former Manson Followers Debate Family's Culpability: "How Can You Point the Finger at Us?"". The Hollywood Reporter. Archived from the original on August 13, 2019. Retrieved August 11, 2019.

- ^ "Helter Skelter (TV Miniseries)". warnerbros.com. Archived from the original on July 5, 2018. Retrieved July 5, 2018.

- ^ Kerekes, David; Slater, David (1996). Killing for Culture. Creation Books. pp. 222–223, 225, 268. ISBN 1-871592-20-8. Archived from the original on May 3, 2017. Retrieved November 18, 2015.

- ^ "John Moran, 'The Manson Family: An Opera' (1990)". rollingstone.com. March 17, 2016. Archived from the original on July 5, 2018. Retrieved July 5, 2018.

- ^ "Assassins". Sondheim.com. November 22, 1963. Archived from the original on November 28, 2010. Retrieved November 28, 2010.

- ^ Roffman, Michael (November 20, 2019). "In 1992, Bob Odenkirk Turned Charles Manson into Lassie and It's Still Hilarious". Consequence Of Sound. Archived from the original on September 3, 2019. Retrieved September 2, 2019.

- ^ "South Park (Classic): "Spooky Fish"/"Merry Christmas, Charlie Manson!"". The A.V. Club. September 16, 2012. Archived from the original on January 9, 2017. Retrieved July 5, 2018.

- ^ Zacharek, Stephanie (August 18, 2002). "Bad Vibrations". The New York Times. Archived from the original on April 29, 2011. Retrieved March 23, 2011.

- ^ "SXSW Review: Unexpected Charmer 'Manson Family Vacation' Starring Jay Duplass". IndieWire. March 19, 2015. Archived from the original on July 5, 2018. Retrieved July 5, 2018.

- ^ Aquarius Official Website Archived September 24, 2014, at the Wayback Machine NBC.

- ^ "How Netflix's Mindhunter Cleverly Set Up Season 2 and Beyond". Vanity Fair. October 17, 2017. Archived from the original on February 13, 2018. Retrieved July 5, 2018.

- ^ Dargis, Manohla (May 9, 2019). "'Charlie Says' Review: Complicating Those Manson Family Values". The New York Times. Archived from the original on February 28, 2022. Retrieved May 11, 2019.

- ^ "All the details of Quentin Tarantino's new movie, which stars Brad Pitt, Leonardo DiCaprio, and Margot Robbie". Business Insider. Archived from the original on June 21, 2018. Retrieved July 5, 2018.

- ^ Tallerico, Brian (September 20, 2019). "Zeroville". Archived from the original on June 24, 2020. Retrieved August 9, 2020.

- Works cited

- Bugliosi, Vincent; Gentry, Curt (1974). Helter Skelter: The True Story of the Manson Murders (1992 ed.). Norton. ISBN 0-09-997500-9.

- Guinn, Jeff (2013). Manson: The Life and Times of Charles Manson. Simon & Schuster. ISBN 978-1-4516-4516-3.

- Manson, Charles (1988). Manson in His Own Words. As told to Nuel Emmons. Grove Press. ISBN 0-8021-3024-0.

- O'Neill, Tom (2019). Piepenbring, Dan (ed.). CHAOS: Charles Manson, the CIA, and the Secret History of the Sixties. ISBN 978-0-316-47755-0.

- Sanders, Ed (2002). The Family (rev. updated ed.). Thunder's Mouth Press. ISBN 1-56025-396-7.

Further reading

- Atkins, Susan with Bob Slosser (1977). Child of Satan, Child of God. Logos International; Plainfield, New Jersey. ISBN 0-88270-276-9.

- Day, James Buddy (2019). Hippie Cult Leader: The Last Words of Charles Manson. Optimum Publishing. ISBN 978-0888902962

- George, Edward; Matera, Dary (1999). Taming the Beast: Charles Manson's Life Behind Bars. St. Martin's Press. ISBN 0-312-20970-3.

- Gilmore, John (2000). Manson: The Unholy Trail of Charlie and the Family. Amok Books. ISBN 1-878923-13-7.

- Gilmore, John (1971). The Garbage People. Omega Press.

- LeBlanc, Jerry; Davis, Ivor (1971). 5 to Die. Holloway House Publishing. ISBN 0-87067-306-8.

- Pellowski, Michael J. (2004). The Charles Manson Murder Trial: A Headline Court Case. Enslow Publishers. ISBN 0-7660-2167-X.

- Schreck, Nikolas (1988). The Manson File. Amok Press. ISBN 0-941693-04-X.

- Schreck, Nikolas (2011). The Manson File, Myth and Reality of an Outlaw Shaman. World Operations. ISBN 978-3-8442-1094-1.

- Udo, Tommy (2002). Charles Manson: Music, Mayhem, Murder. Sanctuary Records. ISBN 1-86074-388-9.

- Watkins, Paul with Guillermo Soledad (1979). My Life with Charles Manson. Bantam. ISBN 0-553-12788-8.

- Watson, Charles. Will You Die for Me? (1978). F. H. Revell. ISBN 0-8007-0912-8.

External links

- FBI file on Charles Manson

- Cease to Exist: The Saga of Dennis Wilson & Charles Manson – compendium of first-hand accounts edited by Jason Austin Penick

Legal documents

- Decision in appeal by Manson from Hinman-Shea conviction People v. Manson, 71 Cal. App. 3d 1 (California Court of Appeal, Second District, Division One, June 23, 1977).

- Decision in appeal by Manson, Atkins, Krenwinkel, and Van Houten from Tate-LaBianca convictions People v. Manson, 61 Cal. App. 3d 102 (California Court of Appeal, Second District, Division One, August 13, 1976). Retrieved June 19, 2007.

News articles

- Dalton, David (October 1998). "If Christ Came Back as a Con Man". gadflyonline.com. – article by co-author of 1970 Rolling Stone story on Manson.

- Linder, Douglas. Famous Trials – The Trial of Charles Manson. University of Missouri at Kansas City Law School. 2002. April 7, 2007.

- Noe, Denise (December 12, 2004). "The Manson Myth". CrimeMagazine.com. Archived from the original on November 21, 2010.

- "Horrific past haunts former cult members". San Francisco Chronicle. August 12, 2009.

- 1934 births

- 2017 deaths

- 20th-century American criminals

- 20th-century apocalypticists

- American conspiracy theorists

- American folk rock musicians

- American male criminals

- American mass murderers

- American neo-Nazis

- American people convicted of murder

- American people who died in prison custody

- American prisoners sentenced to death

- American prisoners sentenced to life imprisonment

- American rapists

- American singer-songwriters

- Anti-black racism in the United States

- Crime in California

- Criminals from California

- Criminals from Ohio

- Deaths from cancer in California

- Deaths from colorectal cancer

- Deaths from respiratory failure

- American former Scientologists

- Founders of new religious movements

- History of Los Angeles

- Manson Family

- Outsider musicians

- People convicted of murder by California

- People from Cincinnati

- People with antisocial personality disorder

- People with schizophrenia

- Prisoners sentenced to death by California

- Prisoners sentenced to life imprisonment by California

- Prisoners who died in California detention

- Self-declared messiahs

- Cult leaders