Walla Walla, Washington

Walla Walla | |

|---|---|

Reynolds–Day Building, Sterling Bank, and Baker Boyer Bank buildings in downtown Walla Walla | |

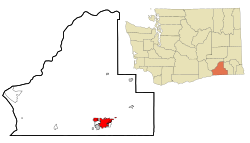

Location of Walla Walla, Washington | |

| Coordinates: 46°3′54″N 118°19′49″W / 46.06500°N 118.33028°W | |

| Country | United States |

| State | Washington |

| County | Walla Walla |

| Government | |

| • Type | Council–manager |

| • Body | City council |

| • Mayor | Tom Scribner |

| • City manager | Nabiel Shawa |

| Area | |

• City | 13.88 sq mi (35.95 km2) |

| • Land | 13.85 sq mi (35.86 km2) |

| • Water | 0.03 sq mi (0.08 km2) |

| Elevation | 942 ft (287 m) |

| Population | |

• City | 34,060 |

• Estimate (2021)[3] | 33,927 |

| • Density | 2,376.14/sq mi (917.42/km2) |

| • Urban | 55,805 (US: 464th) |

| • Metro | 62,682 (US: 382th) |

| Time zone | UTC−8 (PST) |

| • Summer (DST) | UTC−7 (PDT) |

| ZIP Code | 99362 |

| Area code | 509 |

| FIPS code | 53-75775 |

| GNIS feature ID | 1512769[4] |

| Website | wallawallawa.gov |

Walla Walla is a city in and the seat of government of Walla Walla County, Washington, United States.[5] It had a population of 34,060 at the 2020 census,[2] estimated to have decreased to 33,927 as of 2021.[3] The population of the city and its two suburbs, the town of College Place and unincorporated Walla Walla East, is about 45,000.[6]

Walla Walla is in the southeastern region of Washington, approximately four hours away from Portland, Oregon, and four and a half hours from Seattle. It is located only 6 mi (10 km) north of the Oregon border.

History

Native history and early settlement

Walla Walla's history starts in 1806 when the Lewis and Clark expedition encountered the Walawalałáma (Walla Walla people) near the mouth of Walla Walla River. Other inhabitants of the valley included the Liksiyu (Cayuse), Imatalamłáma (Umatilla), and Niimíipu (Nez Perce) indigenous peoples.[7] In 1818, Fort Walla Walla (originally Fort Nez Percés), a fur trading outpost run by Hudson's Bay Company (HBC), was established and operated as an important stopping point in Oregon Country.[8] Abandoned in 1855, it is now underwater behind the McNary Dam.[9]

On October 16, 1836,[10] after news of a Nez Perce[a] expedition to learn about Christianity and a deal was brokered between the Cayuse people for the use of the Waiilatpu region,[11][13][14][15] Calvinist missionaries Marcus and Narcissa Whitman established the Whitman Mission.[16][17] A deep distrust of the settlers was cultivated between the Cayuse and the settlers as the Whitmans struggled to convert the natives, failed to fulfill promises, and shifted their focus to whites passing through along the Oregon Trail.[16][17] In 1847, following a deadly measles outbreak, and reports of the Whitmans poisoning the Cayuse, the Whitmans were warned to leave the area because of the Cayuse custom of killing medicine men whose patients died. They refused to leave, and were killed by the Cayuse, along with 12 others.[16][18][17] The site was later designated as Whitman National Monument, a National Historic Site.[19]

Catholic missionaries also arrived in the 1840s, and the Catholic ceremonies resonated with the tribe.[9][10] On July 24, 1846 Pope Pius IX established the Diocese of Walla Walla. Augustin-Magloire Blanchet was appointed the first Bishop of Walla Walla, but fled shortly after the Whitman massacre. The Diocese of Walla Walla is now a titular see held by Witold Mroziewski, an auxiliary bishop of Brooklyn, New York.[20][21]

In 1855, the Walla Walla Treaty Council was held at Waiilatpu between the Washington Territorial Assembly and the tribal leaders of the surrounding area. Despite the indigenous people citing Tamanwit (natural law), the following year the natives agreed to surrender millions of acres of land for a native reservation and $150,000.[7][22][23][24] The Umatilla Indian Reservation's boundaries eventually shrunk to less than 200,000 of acreage.[25]

Founding

The Walla Walla treaty remained unratified for four years, during which time the conflict between the natives and settlers was increasing due to frontiersmen encroaching on the promised reservation and the Walla Walla and Umatilla peoples' refusal to move to the Umatilla Indian Reservation.[26][27] The United States Army established a presence in a series of military forts beginning in 1856. A community named "Steptoeville" grew around Fort Walla Walla, named for Lieutenant Colonel Edward Steptoe, and later his name was bestowed upon Steptoe, Washington.[8][28] The fort has since been restored with a museum about the early settlers' lives.[29][9][30]

Growth in the region was limited due to a ban on immigration to the area due to the constant warring with the natives from the Department of the Pacific's General John Ellis Wool, who was sympathetic to the natives.[26][31] In 1858, the department was split, leaving Washington territory under the command of General William S. Harney, who lifted the ban on October 31, 1858.[26][31] Thousands of pioneers swarmed to the area, creating a burgeoning farming and mining community.[32]

On March 15, 1859, Walla Walla county held its first county commission and election in the community's first church, St. Patrick's Church, which still serves as the city's parish.[21][33] Following the ratification of the Walla Walla treaty,[29][34][35] the commission voted to name the settlement Walla Walla, on November 17, 1859[36] and the military carried out the forced displacement of the remaining natives, under the threat of hanging.[37][38]

On December 20, 1859, the first educational charter was granted to Whitman Seminary, a high school, which opened on October 15, 1866. In 1882, the institution's name was changed to Whitman College, and the legislature issued a new educational charter as a four-year private college.[39]

The Mullan Road, the first wagon road to cross the Rocky Mountains into the Pacific Northwest, tied Walla Walla to more mining opportunities, and after gold was discovered in 1860, the area became the outfitting point for the Oro Fino, Idaho mines.[40][41] The nearest part of the road followed the modern approximate path from Spokane to Walla Walla via Interstate 90, U.S. Route 195, and U.S. Route 12.[42] The population swelled due to the gold rush, resulting in an unsuccessful proposal to Congress to split Walla Walla from Washington into its own territory.[43]

Gold rush and growth

Walla Walla was incorporated on January 11, 1862.[44] The first election was held on April 1, 1862, and Judge Elias Bean Whitman, Marcus Whitman's cousin, was elected as the city's first mayor.[32][43][45][46] The population exploded over the following decade to 300% its size, making it the largest city in the territory, slating it to be the capital until cities surpassed it again, after it was bypassed by the transcontinental rail lines in the 1880s.[47][43][48]

During the 1860s, the city established its first businesses and community gathering spaces, a number of which served as the first in Pacific Northwest. The city's first newspaper was one of the first between Missouri and the Cascades, the Washington Statesman, was founded in 1861.[49][50][51] The first bank, Baker Boyer Bank, was the first in the state, was founded in 1869[52] by one of the city's first council members,[43] Dorsey Syng Baker and his brother-in-law John Franklin Boyer,[48][53][39][54] and as of March 2022, still served as the oldest bank in state.[55] The Pioneer Meat Market, run by partners John Dooley and William Kirkman, was opened during this time and remained there until they sold it to Christopher Ennis in 1882 and founded the Walla Walla Dressed Meat Company.[56][57][58][59]

One of the first brick buildings in the city was also Walla Walla's first store, Schwabacher Brothers Store on Main street, which served as the city's grocer, builder supply, and clothes shop. Sigmond Schwabacher, one of the brothers, also served in the city's council.[60] The city's first book store was opened in 1864, and an academic community formed around the city's book collection as the Calliopean Society and later incorporated as the Walla Walla Library Association.[61][62] The city also had one of the region's first breweries,[63] Emil Meyer's City Brewery,[64] that also served as a bakery.[65] Downtown also hosted a post office, several hotels, restaurants, a bathhouse and shaving saloon, a liquor store, a drugstore, and several manufactories.[65][66]

During the gold rush, large populations of Chinese settlers arrived in the city from Portland, Oregon, creating a neighborhood referred to as "Chinatown".[67] The Chinese settlers mainly worked in commerce, mining, and railroad contracts. After Mullan was unable to lobby the state to make Walla Walla a major railroad stop, and a fire in Chinatown destroyed most of the neighborhood, the immigrants left to find work elsewhere,[68][69] including Eng Ah King, who was informally known as the "mayor of Chinatown" for revitalizing Seattle's Chinatown.[70][71]

In 1886, while Washington was lobbying for statehood, local business man Levi Ankeny donated 160 acres of land to the city to serve as the site of a new prison. Legislators approved the site, and in 1887, the state began transferring prisoners to the Washington Territorial Prison from Saatco Prison, a privately owned facility that was shut down in 1888 because of its poor living conditions.[72][73] The first inmate was a local, William Murphy, who was serving an 18-year sentence for manslaughter.[74] There have been many prison escapes attempted in the prison's history.[75][76][77][78] In 1887, the prison took in its first woman inmate, and had to improvise accommodations until a separate facility was built nearby.[72][79] When Washington became a state in 1889, the facility officially became the Washington State Penitentiary, but inmates nicknamed it "The Hill", "The Joint", "The Walls", and "The Pen".[72]

Agricultural center

As the gold rush died out, the city developed into an agricultural center referred to as the "cradle of Pacific Northwest history",[43][48] and the "garden city",[66] a popular source for onions, apples, peas, and wine grapes.[29]

Italian settlers from Lonate Pozzolo and Calabria regions formed the core of the gardening industry, and settled in neighborhoods known as "Blalock" and the "South Ninth".[32][80][81] One of the main contributions of the Italians to Walla Walla commerce was their vineyards, and soon after, wine tasting rooms, the first two opening in the 1880s by Frank Orselli and Pasquale Saturno.[82][59] The Italian Walla Walla population was also responsible for growing Washington State's official vegetable,[83] the Walla Walla sweet onion.[32][80][81]

It was the technique of dryland farming, though, that made Walla Walla the region's breadbasket known for its wheat exports.[32][39] The cultivating of grains brought hundreds of Seventh-day Adventists (SDA) to the city, building Walla Walla College and the Walla Walla Sanitarium.[84][85] The SDA population was followed by hundreds of Volga Germans, whose Old Lutheran and Mennonite religions were connected to SDA in Prussia. The immigrants had relied on dryland farming of wheat crops in Volgograd, Russia.[86] The neighborhood built around the Russian-German immigrants is known as "Germantown" or "Russische Ecke (Russian Corner)" to locals, referring to the creek that runs through it as "Little Volga".[87] The area around Walla Walla College eventually incorporated as its own city, College Place, Washington.[88]

German immigrants also grew hops and the city was home to several breweries.[89][64] By the 1890s, wine, beer, liquor, and tobacco taxes accounted for 90% of the city's revenue,[66] but the alcohol industries died out with Prohibition in the United States.[64][90][91]

As the city became dependent on its wheat production, merchants in the town financed a railroad to Wallula, Washington, to connect Walla Walla to the Columbia river, completed in 1875.[92][32][39]

20th century

In 1911, Walla Walla adopted a mayor–council government referred to as a "commission" form of government. In 1954, after Sunnyside, Washington adopted another form of government, council–manager government, voted down a change to council-manager, but on November 4, 1959, the city's residents voted to adopt the government form.[43]

Walla Walla's second movie theater, American Theater, opened in 1917 showing The Law of Compensation, a Selznick Pictures film starring Norma Talmadge. The theater later was sold and renamed to Liberty, and eventually became a department store around the 1930s.[93] In 1990, became Walla Walla's first privately renovated building as a Bon-Macy's.[94][95][96] Bon-Macy's parent-company, Federated Department Stores, rebranded all of its subsidiaries to Macy's, which operated in the Liberty building until 2020.[97][98]

In 1927, the Real Estate Improvement Company of Seattle invested $300,000 toward the construction of the Marcus Whitman Hotel. The 174-room hotel was designed by Sherwood D. Ford and opened in 1928. It fell into disrepair in the 1960s, until it was restored in 1999 and re-opened in 2001.[32][99][66][100] As of March 2022[update], the hotel was still open.[101]

Mill Creek overflowed into Walla Walla and College Place on March 31, 1931, causing $1 million in damages. Community volunteers jury-rigged makeshift levees to divert water from buildings during the cleanup which cost roughly $100,000. The United States Army Corps of Engineers built the Mill Creek Dam and Bennington Lake in response to the disaster.[32][93][102] The dam and lake were instrumental in preventing damage from flooding in 1964, 1996, and 2020.[103]

During the Great Depression, a Canadian import duty cut off the main market for Walla Walla's fresh agriculture. John Grant Kelly, who owned the Walla Walla Union-Bulletin at the time, opened the area's first cannery, Walla Walla Canning Company. In 1939, Walla Walla produced roughly $5 million of the country's $30 million canned green pea industry, and TIME magazine referred to Kelly as the "Father of Peas".[104][32][105] Kelly also owned Church Grape Juice Company, a concord grape farm in Kennewick, Washington. Workers went on strike for better wages in September 1949, and Kelly had two employees arrested for speaking to the Tri-City Herald. Church was one of four juice companies in the region to be charged with violations of the Sherman Antitrust Act of 1890 for price-fixing grapes. Welch's bought Church from Kelly in 1952.[106][107]

In 1936, Walla Walla and surrounding areas were struck by the magnitude 6.1 State Line earthquake. Residents reported hearing a moderate rumbling immediately before the shock. There was significant damage in the area, and aftershocks were felt for several months following.[108]

in the 1970s and 1980s, Leonetti Cellar, Woodward Canyon, L'Ecole 41, Waterbrook Winery and Seven Hills Winery pioneered a resurgence of Walla Walla's viticulture.[32][109][110]

In 1997, Gary Johnson founded the first brewery in Walla Walla since prohibition, Mill Creek Brewpub.[63]

21st century

In 2001, Walla Walla was a Great American Main Street Award winner for the transformation and preservation of its once dilapidated main street.[111] In July 2011, USA Today selected Walla Walla as the friendliest small city in the United States.[112] Walla Walla was also named Friendliest Small Town in America the same year as part of Rand McNally's annual Best of the Road contest. In 2012 and 2013 Walla Walla was a runner-up in the best food category for the Best of the Road.[113][114] Downtown Walla Walla was awarded a Great Places in America Great Neighborhood designation in 2012 by the American Planning Association.[115][116]

In the 2010s, Walla Walla's brewery industry experienced a revival.[117] The first hops farms since prohibition were planted in 2018,[91][118] and in 2019, Washington State Department of Corrections announced a plan to bring a vineyard and hopyard to Washington State Penitentiary, along with agricultural science education to prepare inmates for careers in the field. The program would offer inmates state-wide minimum wages, a practice only legally enforced by state law at private institutions.[119][120] The city hosted its first beer festival in February 2020.[121]

In 2017, and annually, Walla Walla's mayor signed a proclamation making the third Saturday of September "Adam West Day", to honor the actor who was born and raised in the city.[122][123][124][125] In 2020, the event was cancelled due to the COVID-19 pandemic, but the organizers announced that the city approved the erection of a statue in West's honor and a GoFundMe fundraiser to cover the costs of the statue. The statue will be placed in Menlo Park on Alvarado Terrace, part of Historic Downtown Walla Walla.[126][127]

Etymology

Tourists to Walla Walla are often told that it is a "town so nice they named it twice".[128] The slogan was coined by Al Jolson, who had visited the city in the early 1900s in The Keylor Grand Theater. He had also said the same of New York, New York.[32] The quote referring to Walla Walla was in The Jolson Story, a musical about the entertainer's life.[129]

Some locals and Walla Walla natives often refer to the city in text form with "W2".[130]

Walla Walla is Nez Perce for "Place of Many Waters", because the original settlement was at the junction of the Snake and Columbia rivers.[29]

In popular culture

Walla Walla is humorously mentioned in Pogo in an alternate lyrical version of "Deck the Halls", a traditional Christmas carol.[131] Walla Walla is the location of the treasure in The Three Stooges film Cash and Carry.[132] In a Merrie Melodies short, Transylvania 6-5000, "Walla Walla, Washington" is a magic word that can transform Count Bloodcount.[133] Walla Walla is also the hometown of several fictional companies in other Merrie Melodies shorts, including A Mouse Divided, The High and the Flighty, and This Is a Life?[134][135][136]

Geography and climate

Walla Walla is located in the Walla Walla Valley, with the rolling Palouse hills and the Blue Mountains to the east of town. Various creeks meander through town before combining to become the Walla Walla River, which drains into the Columbia River about 30 miles (50 km) west of town. The city lies in the rain shadow of the Cascade Mountains, so annual precipitation is fairly low.

According to the United States Census Bureau, the city has a total area of 12.84 square miles (33.26 km2), of which 12.81 square miles (33.18 km2) is land and 0.03 square miles (0.08 km2) is water.[137][138]

Walla Walla has a hot-summer Mediterranean climate according to the Köppen climate classification system (Köppen: Csa). It is one of the northernmost locations in North America to qualify as having such a climate. In contrast to most other locations having this climate type in North America, Walla Walla can experience fairly cold winter conditions, though they are still relatively mild for its latitude and inland location.

| Climate data for Walla Walla, Washington (Walla Walla Regional Airport), 1991–2020 normals, extremes 1949–present | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Record high °F (°C) | 70 (21) |

75 (24) |

79 (26) |

96 (36) |

100 (38) |

116 (47) |

114 (46) |

114 (46) |

104 (40) |

89 (32) |

81 (27) |

71 (22) |

116 (47) |

| Mean maximum °F (°C) | 61.3 (16.3) |

62.0 (16.7) |

69.8 (21.0) |

78.1 (25.6) |

88.9 (31.6) |

97.0 (36.1) |

104.2 (40.1) |

102.3 (39.1) |

92.5 (33.6) |

79.0 (26.1) |

66.6 (19.2) |

61.0 (16.1) |

105.7 (40.9) |

| Mean daily maximum °F (°C) | 41.9 (5.5) |

46.5 (8.1) |

55.8 (13.2) |

62.5 (16.9) |

71.4 (21.9) |

79.0 (26.1) |

90.1 (32.3) |

88.6 (31.4) |

78.5 (25.8) |

63.4 (17.4) |

49.2 (9.6) |

41.0 (5.0) |

64.0 (17.8) |

| Daily mean °F (°C) | 36.3 (2.4) |

39.7 (4.3) |

46.8 (8.2) |

52.5 (11.4) |

60.4 (15.8) |

67.0 (19.4) |

76.3 (24.6) |

75.2 (24.0) |

66.2 (19.0) |

53.9 (12.2) |

43.9 (6.6) |

35.6 (2.0) |

54.3 (12.4) |

| Mean daily minimum °F (°C) | 30.7 (−0.7) |

32.9 (0.5) |

37.8 (3.2) |

42.5 (5.8) |

49.3 (9.6) |

55.1 (12.8) |

62.4 (16.9) |

61.7 (16.5) |

53.9 (12.2) |

43.9 (6.6) |

35.6 (2.0) |

30.2 (−1.0) |

44.7 (7.1) |

| Mean minimum °F (°C) | 16.3 (−8.7) |

20.2 (−6.6) |

26.8 (−2.9) |

32.3 (0.2) |

37.9 (3.3) |

45.4 (7.4) |

51.4 (10.8) |

50.6 (10.3) |

41.8 (5.4) |

30.1 (−1.1) |

21.7 (−5.7) |

15.4 (−9.2) |

8.4 (−13.1) |

| Record low °F (°C) | −18 (−28) |

−16 (−27) |

4 (−16) |

20 (−7) |

26 (−3) |

36 (2) |

40 (4) |

42 (6) |

32 (0) |

15 (−9) |

−11 (−24) |

−24 (−31) |

−24 (−31) |

| Average precipitation inches (mm) | 2.10 (53) |

1.59 (40) |

2.11 (54) |

1.98 (50) |

2.07 (53) |

1.24 (31) |

0.47 (12) |

0.40 (10) |

0.64 (16) |

1.66 (42) |

2.25 (57) |

2.23 (57) |

18.74 (476) |

| Average snowfall inches (cm) | 1.0 (2.5) |

2.2 (5.6) |

0.2 (0.51) |

0.0 (0.0) |

0.0 (0.0) |

0.0 (0.0) |

0.0 (0.0) |

0.0 (0.0) |

0.0 (0.0) |

0.1 (0.25) |

0.3 (0.76) |

2.7 (6.9) |

6.5 (17) |

| Average precipitation days (≥ 0.01 in) | 13.3 | 11.2 | 12.1 | 11.1 | 9.8 | 7.1 | 2.7 | 2.5 | 3.8 | 8.8 | 13.1 | 13.6 | 109.1 |

| Average snowy days (≥ 0.1 in) | 2.3 | 1.5 | 0.3 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.1 | 0.5 | 2.4 | 7.1 |

| Mean monthly sunshine hours | 50.5 | 83.4 | 173.8 | 221.7 | 288.5 | 326.3 | 384.5 | 344.4 | 268.8 | 199.2 | 67.8 | 40.3 | 2,449.2 |

| Percent possible sunshine | 18 | 29 | 47 | 54 | 62 | 69 | 81 | 79 | 71 | 59 | 24 | 15 | 51 |

| Source: NOAA (sun 1961–1987)[139][140][141] | |||||||||||||

Demographics

| Census | Pop. | Note | %± |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1870 | 1,394 | — | |

| 1880 | 3,588 | 157.4% | |

| 1890 | 4,709 | 31.2% | |

| 1900 | 10,049 | 113.4% | |

| 1910 | 19,364 | 92.7% | |

| 1920 | 15,503 | −19.9% | |

| 1930 | 15,976 | 3.1% | |

| 1940 | 18,109 | 13.4% | |

| 1950 | 24,102 | 33.1% | |

| 1960 | 24,536 | 1.8% | |

| 1970 | 23,619 | −3.7% | |

| 1980 | 25,618 | 8.5% | |

| 1990 | 26,478 | 3.4% | |

| 2000 | 29,686 | 12.1% | |

| 2010 | 31,731 | 6.9% | |

| 2020 | 34,060 | 7.3% | |

| 2021 (est.) | 33,927 | [3] | −0.4% |

| U.S. Decennial Census[142] 2020 Census[2] | |||

2020 census

As of the census of 2020, there were 34,060 people and 12,414 householders residing in the city. The population density was 2,478.1 inhabitants per square mile (956.8/km2).[143]

2010 census

As of the census of 2010, there were 31,731 people, 11,537 households, and 6,834 families residing in the city. The population density was 2,477.0 inhabitants per square mile (956.4/km2). There were 12,514 housing units at an average density of 976.9 per square mile (377.2/km2). The racial makeup of the city was 81.6% White, 2.7% African American, 1.3% Native American, 1.4% Asian, 0.3% Pacific Islander, 9.1% from other races, and 3.6% from two or more races. Hispanic or Latino residents of any race were 22.0% of the population.[143]

There were 11,537 households, of which 30.4% had children under the age of 18 living with them, 42.6% were married couples living together, 12.0% had a female householder with no husband present, 4.7% had a male householder with no wife present, and 40.8% were other forms of households. 33.4% of all households were made up of individuals, and 14.2% had someone living alone who was 65 years of age or older. The average household size was 2.43 and the average family size was 3.10.[143]

The median age in the city was 34.4 years. 22% of residents were under the age of 18; 14.5% were between the ages of 18 and 24; 26.2% were from 25 to 44; 23.1% were from 45 to 64; and 14% were 65 years of age or older. The gender makeup of the city was 51.9% male and 48.1% female.[143]

2000 census

As of the census of 2000, there were 29,686 people, 10,596 households, and 6,527 families residing in the city. The population density was 2,744.9 people per square mile (1,059.3/km2). There were 11,400 housing units at an average density of 1,054.1 per square mile (406.8/km2). The racial makeup of the city was 83.79% White, 2.58% African American, 1.05% Native American, 1.24% Asian, 0.23% Pacific Islander, 8.26% from other races, and 2.85% from two or more races. Hispanic or Latino of any race were 17.42% of the population.[143]

There were 10,596 households, of which 30.6% had children under the age of 18 living with them, 46.4% were married couples living together, 11.0% had a female householder with no husband present, and 38.4% were other forms of households. 31.9% of all households were made up of individuals, and 15.1% had someone living alone who was 65 years of age or older. The average household size was 2.44 and the average family size was 3.08.[143]

In the city, 21.8% of the population was under the age of 18, 14.2% was from 18 to 24, 26.5% from 25 to 44, 17.5% from 45 to 64, and 20.1% was 65 years of age or older. The median age was 34 years. For every 100 females, there were 108.4 males. For every 100 females age 18 and over, there were 109.1 males.[143]

The median income for a household in the city was $31,855, and the median income for a family was $40,856. Men had a median income of $31,753 versus $23,889 for women. The per capita income for the city was $15,792. About 13.1% of families and 18.0% of the population were below the poverty line, including 22.8% of those under the age of 18 and 10.5% of those aged 65 and older.[143]

Economy and infrastructure

Agriculture

Though wheat is still a big crop, vineyards and wineries have become economically important over the last three decades.[144] In summer 2020, there were over 120 wineries in the greater Walla Walla area. Following the wine boom, the town has developed several fine dining establishments and luxury hotels. The Marcus Whitman Hotel, originally opened in 1928, was renovated with original fixtures and furniture. It is the tallest building in the city, at 13 stories.

The Walla Walla Sweet Onion and the Great Grape are a few crops with a rich tradition. Over a century ago on the Island of Corsica, off the west coast of Italy, a French soldier named Peter Pieri found an Italian sweet onion seed and brought it to the Walla Walla Valley. Impressed by the new onion's winter hardiness, Pieri, and the Italian immigrant farmers who comprised much of Walla Walla's gardening industry, harvested the seed.[80][145][146]

The sweet onion developed over several generations through the process of selecting onions from each year's crop, targeting sweetness, size and round shape. The Walla Walla Sweet Onion is designated under federal law as a protected agricultural crop. In 2007 the Walla Walla Sweet Onion became Washington's official state vegetable.[147] There is also a Walla Walla Sweet Onion Festival, held annually in July. Walla Walla Sweet Onions have low sulfur content (about half that of an ordinary yellow onion) and are 90 percent water.

Walla Walla currently has two farmers markets, both held from May until October. The first is located on the corner of 4th and Main, and is coordinated by the Downtown Walla Walla Foundation. The other is at the Walla Walla County Fairgrounds on S. Ninth Ave, run by the Walla Walla Valley Farmer's Market.[148]

Wine industry

Walla Walla has experienced an expansion in its wine industry in recent decades, culminating in the area being named "Best Wine Region" in USA Today's Reader Choice Awards in both 2020 and 2021.[149][150] Several local wineries have received top scores from wine publications such as Wine Spectator, The Wine Advocate and Wine and Spirits. Although most of the early recognition went to the wines made from Merlot and Cabernet, Syrah is fast becoming a star varietal in this appellation.[151] Overall, there are more than 120 wineries in the Walla Walla area, which collectively generate over $100 million for the valley annually.[152][153]

Walla Walla Community College offers an associate degree (AAAS) in winemaking and grape growing through its Center for Enology and Viticulture, which operates its own commercial winery, College Cellars.[154]

One challenge to growing grapes in Walla Walla Valley is the risk of a killing freeze during the winter. On average these happen once every six or seven years; the penultimate occurrence (in 2004) destroyed about 75% of the wine grape crop in the valley. In November 2010 the valley was again hit with a killing frost, leading to a 28% decline in Cabernet Sauvignon production, a 20% decline in red grape production, and an overall decline in production of 11% (red and white varietals).[155]

Corrections industry

The second-largest prison in Washington, after nearby Coyote Ridge Corrections Center in Connell, is the Washington State Penitentiary (WSP) located in Walla Walla, at 1313 North 13th. Originally opened in 1886, it now houses about 2,000 offenders.[156] In addition, there are about 1000 staff members. In 2005, the financial benefit to the local economy was estimated to be about $55 million through salaries, medical services, utilities, and local purchases. In 2014, the penitentiary underwent an extensive expansion project to increase the prison capacity to 2,500 violent offenders and double the staff size.[157]

Until October 11, 2018, Washington was a death penalty state, and occasional executions took place at the state penitentiary; the last execution took place on September 10, 2010.[158][159] Washington was also one of the last two states to allow hanging as a choice when sentenced to death[160] (the other being New Hampshire); there has not been a hanging since May 1994 (the default method of execution was changed to lethal injection in 1996). Washington was the last state with an active gallows.[161] 80 executions were carried out at the prison between 1904 and 2010.[162]

The most notable inmate has been Gary Ridgway, a serial killer known as the "Green River killer", who was still incarcerated there as of November 2021.[163]

Healthcare

Walla Walla is served by two health care institutions: St. Mary Medical Center (part of the Catholic Providence Health System) and the Jonathan M. Wainwright Veteran's Affairs Medical Center on the grounds of the old Fort Walla Walla and World War II training facility.

Transportation

Transportation to Walla Walla includes service by air through Walla Walla Regional Airport, several railroads, and highway access primarily from U.S. Route 12. The Washington State Department of Transportation is engaged in a long-term process of widening this road into a four-lane divided highway between Pasco and Walla Walla, with major portions scheduled to be complete in 2022.[164] The highway also acts as the main gateway to Interstates 82 and 84, which run to the west and south, respectively.[165] State Route 125 runs through the city, north to State Route 124 in Prescott and south to Milton-Freewater, Oregon, becoming Oregon Highway 11 at the state line.[citation needed]

There are four major bus services in the area connecting the region's cities. Walla Walla and nearby College Place are served by Valley Transit, a typical multi-route city bus service. The city of Milton-Freewater, OR has a single-line bus service with several stops in town with two stops in College Place and five in Walla Walla. Travel Washington's Grape Line is a 104-mile (167 km) intercity service between Walla Walla and Pasco that runs three times a day. Finally, Confederated Tribes of the Umatilla Indian Reservation operates a Kayak bus to Pendleton, with four trips each weekday and two trips each Saturday via its Walla Walla Whistler route.[166]

Walla Walla Tours

Walla Walla has tours for adults and kids. Seattle Ballooning provides hot air balloon rides and tours over Walla Walla's most famous vineyards. There are also a variety of wine tours for tourists to enjoy.

Walla Walla Festivals

The Walla Walla Balloon Festival or otherwise known as the Walla Walla Balloon Stampede, is one of the oldest hot air balloon events in the US. The date changes each year but is either on Mother's Day Weekend or in Mid October.

Sports

Walla Walla is home of the Walla Walla Sweets, a summer collegiate baseball team that plays in the West Coast League. The league comprises college players and prospects working towards a professional baseball career. Teams are located in British Columbia, Oregon, Washington and Alberta. Sweets home games have been played at Borleske Stadium in Walla Walla, since their first season in 2010. In only their second season the Sweets played in the WCL Championship game, ultimately losing to the Corvallis Knights. In 2013, the Sweets won their first North Division title with the second best win–loss record in the WCL. The Sweets lost their North Division playoff series to the Wenatchee Applesox that year.

Walla Walla Drag Strip is an 1/8 mile dragstrip west of the Walla Walla Regional Airport. The dragstrip is located on an old runway of the airport.

There also is a women's flat track roller derby league called the Walla Walla Sweets Rollergirls, their practices and games are played at the Walla Walla YMCA.

Walla Walla is the location of Tour of Walla Walla, a four-stage road cycling race held annually in April. The races are held in Walla Walla and in the Palouse hills of nearby Waitsburg. The stages include two road races, a time trial, and a criterium race.[167]

The annual Walla Walla Marathon takes place in October and includes a full marathon, half-marathon, and 10k race. The full marathon is a Boston Marathon Qualifier.[168] The race route winds through the streets of the city of Walla Walla and the country roads outside of town, often running past several of the region's many estate vineyards.

Fine and performing arts

The Walla Walla Valley boasts a number of fine and performing arts organizations and venues.

- The Walla Walla Valley Bands were formed in 1989 and currently boasts a Concert Band of more than 70 and two Jazz Ensembles. The group rehearses weekly on Tuesday nights at the Walla Walla Valley Adventist Academy in nearby College Place.

- The Walla Walla Symphony began in 1907[169] and performs six to eight concerts from October - May. Its primary performance venue is Cordiner Hall on the campus of Whitman College. Other performance venues include the Gesa Power House Theatre and Walla Walla University Church.

- The Walla Walla Chamber Music Festival is held twice a year and features guest musical ensembles playing classical chamber music in various small venues throughout town. The summer festival includes performances for almost the whole month of June. The winter festival is a small-scale version of the summer program, it is held in mid-January.[170]

- Shakespeare Walla Walla is a non-profit organization that hosts a summer Shakespeare festival in Walla Walla. They often bring Shakespeare troupes from Seattle and elsewhere to perform about four plays per year. In the past this was done at the Fort Walla Walla Amphitheater, but more recently at the GESA Powerhouse Theatre.[171]

- The GESA Powerhouse Theatre opened in 2011 in Walla Walla; it was originally the Walla Walla gas plant, hence its name. Its dimensions closely resemble the Blackfriars Theatre once used by William Shakespeare.[172] The venue is used by Shakespeare Walla Walla as well as host to various concerts and other performing arts events throughout the year.

- The Little Theatre of Walla Walla began in 1944 and moved into its current building on Sumach St. in 1948 where it has performed various plays to this day.[173]

- The Walla Walla Choral Society began in 1980 and performs a season of three or four concerts per year in various locations around the Walla Walla Valley.

- Fort Walla Walla Amphitheater is a disused open-air stage with bench seating on the grounds of the Fort Walla Walla Park, next to Fort Walla Walla Museum. It formerly hosted Shakespeare Walla Walla productions and the Walla Walla Community College Summer Musical.

- The Walla Walla Foundry was founded in 1980.[174]

In addition, the area's three colleges—Whitman College, Walla Walla University and Walla Walla Community College as well as its largest public high school—Walla Walla High School—stage theater and music performances.

Education

Walla Walla is primarily served by Walla Walla Public Schools, which includes seven elementary schools (one is in Dixie, six of them are K-5 with one of these being PreK-5), two middle schools, one traditional high school (colloquially Wa-Hi), and two alternative high schools (Lincoln and Opportunity). There is also Homelink, an alternative K-8 education program which is a hybrid of homeschooling and public school programs.[175]

There are several private Christian schools in the area. These include:

- The Walla Walla Catholic Schools (Assumption K-8 School and DeSales High School)

- Liberty Christian School, non-denominational

- Rogers Adventist School and Walla Walla Valley Academy, in nearby College Place, both of Seventh-day Adventist affiliation

- Saint Basil Academy of Classical Studies (K-8)

In addition to these, there are three colleges in the area:

- Walla Walla Community College, co-winner of the 2013 Aspen Prize for Community College Excellence[176]

- Whitman College, an independent liberal arts college

- Walla Walla University, in nearby College Place, Washington, affiliated with the Seventh-day Adventist denomination

Sister cities

In 1972, Walla Walla established a sister city relationship with Sasayama (now named Tamba-Sasayama), Japan. The two cities have since named roads after their counterpart sister city. Walla Walla has also hosted exchange students from Tamba-Sasayama since 1994 for a two-week home-stay experience. Yearlong high school student exchanges between the cities have occurred several times in the past. Cultural/art exchanges involving music, dance, and various art mediums have also occurred. The Walla Walla Sister City Committee has been the recipient of the Washington State Sister City Association Peace Prize in 2011 and 2014 for their involvement in promoting peace, cultural understanding and friendship.[177][178][179]

Notable people

This section needs additional citations for verification. (April 2019) |

- Burl Barer, broadcaster and author

- Drew Bledsoe, NFL quarterback

- Richard Arthur Bogle, businessman and rancher

- Walter Brattain, Nobel Prize winner and co-inventor of the transistor

- Evelyn Evelyn, baroque pop duo created by Amanda Palmer and Jason Webley

- Robert Brode, physicist

- Wallace R. Brode, scientist

- Robert Clodius, educator and university administrator

- Alex Deccio, Politician. Former member of Washington House of Representatives and Washington State Senate.[180][181]

- Eddie Feigner, softball player

- Bert Hadley, actor and makeup artist

- Gladys Ingle - 4th licensed pilot in USA, wing-walker display performer.

- Alan W. Jones. US Army major general[182][183]

- Charly Martin, NFL player[184]

- Edward P. Morgan, television and newspaper journalist

- Walt Minnick, U.S. Congressman

- Mikha'il Na'ima, writer and philosopher

- David R. Nygren, physicist, inventor of the Time Projection Chamber

- Eric O'Flaherty, MLB player[185]

- Charles Potts, poet and publisher

- Cher Scarlett, software engineer and labor activist[186]

- Hope Summers, actress

- Connor Trinneer, actor

- Jonathan Wainwright, U.S. general

- Ferris Webster, film editor

- Adam West, television and film actor[122]

- Hamza Yusuf, Islamic scholar

- Tonya Cooley, Real World Chicago housemate

- Sally Buzbee, Executive Editor of the Washington Post, former Executive Editor of the Associated Press

See also

Notes

- ^ Some sources say that Flathead (Bitterroot Salish) delegates were sent, but the Nez Perce tribe has claimed all four delegates as belonging to their tribes. It has been suggested that "Flathead" was being used to describe the Nez Perce appearance, rather than the tribe.[11][12]

References

- ^ "2019 U.S. Gazetteer Files". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved August 7, 2020.

- ^ a b c "Explore Census Data". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved June 23, 2022.

- ^ a b c "City and Town Population Totals: 2020-2021". United States Census Bureau. June 23, 2022. Retrieved June 23, 2022.

- ^ "US Board on Geographic Names". United States Geological Survey. October 25, 2007. Retrieved January 31, 2008.

- ^ "Find a County". National Association of Counties. Retrieved June 7, 2011.

- ^ "Official Population Estimates". Washington State Office of Financial Management. Retrieved December 24, 2013.

- ^ a b Paulus, Michael J. Jr. (February 7, 2008). "Town of Walla Walla is named on November 17, 1859". HistoryLink. Retrieved February 21, 2022.

- ^ a b "The Many Fort Walla Wallas –- Whitman Mission National Historic Site". National Park Service. Retrieved February 20, 2022.

- ^ a b c Colt Denfeld, Duane (July 9, 2011). "Fort Walla Walla". HistoryLink. Retrieved February 20, 2022.

- ^ a b Wilma, David (February 14, 2003). "Dr. Marcus Whitman establishes a mission at Waiilatpu on October 16, 1836". HistoryLink. Retrieved February 21, 2022.

- ^ a b Haines, Francis (1937). "The Nez Percé Delegation to St. Louis in 1831". Pacific Historical Review. 6 (1): 71–78. doi:10.2307/3634109. ISSN 0030-8684. JSTOR 3634109.

- ^ Bell, Kim (March 30, 2003). "Nez Perce ceremony "reclaims" two Indians". St. Louis Post-Dispatch. pp. C13.

- ^ Prucha, Francis Paul (1986). The great father : the United States government and the American Indians (Abridged ed.). Lincoln. ISBN 978-0-8032-8712-9. OCLC 12021586.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ^ Drury, Clifford M. (1939). "The Nez Perce "Delegation" of 1831". Oregon Historical Quarterly. 40 (3): 283–287. ISSN 0030-4727. JSTOR 20611199.

- ^ Lyman, William Denison (2020). Lyman's History of old Walla Walla County. Outlook Verlag. ISBN 978-3752433838.

- ^ a b c Harden, Blaine (2021). Murder at the mission : a frontier killing, its legacy of lies, and the taking of the American West. Jeffrey L. Ward. [New York]. ISBN 978-0-525-56166-8. OCLC 1226073551.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ^ a b c Belknap, George N. (1961). "Authentic Account of the Murder of Dr. Whitman: The History of a Pamphlet". The Papers of the Bibliographical Society of America. 55 (4): 319–346. doi:10.1086/pbsa.55.4.24299944. ISSN 0006-128X. JSTOR 24299944. S2CID 193120962.

- ^ Tate, Cassandra (April 16, 2010). "Trial of five Cayuse accused of Whitman murder begins on May 21, 1850". HistoryLink. Retrieved March 4, 2022.

- ^ "Park Archives: Whitman Mission National Historic Site". npshistory.com. Retrieved February 27, 2022.

- ^ "Titular Episcopal See of Walla Walla". GCatholic. Retrieved October 9, 2018.

- ^ a b Paulus, Michael J. Jr. (August 17, 2010). "Catholicism in the Walla Walla Valley". HistoryLink. Retrieved February 21, 2022.

- ^ Nisbet, Jack (May 20, 2008). "Artist Gustavus Sohon documents the Walla Walla treaty council in May, 1855". HistoryLink. Retrieved February 21, 2022.

- ^ "Treaty of Walla Walla, 1855 | GOIA". goia.wa.gov. Retrieved February 21, 2022.

- ^ Trafzer, Cliff (October 22, 2018). "Walla Walla Treaty Council 1855". Oregon Encyclopedia. Retrieved February 20, 2022.

- ^ Tate, Cassandra (April 3, 2013). "Cayuse Indians". HistoryLink. Retrieved February 22, 2022.

- ^ a b c Clark, Robert Carlton (1935). "Military History of Oregon, 1849-59". Oregon Historical Quarterly. 36 (1): 14–59. ISSN 0030-4727. JSTOR 20610911.

- ^ "Umatilla Relationships with US - Making Treaties". trailtribes.org. Archived from the original on January 20, 2022. Retrieved February 22, 2022.

- ^ Meany, Edmond S. (1923). Origin of Washington geographic names. Seattle: University of Washington press. ISBN 933314241X.

- ^ a b c d Paulus, Michael J. Jr. (February 7, 2008). "Town of Walla Walla is named on November 17, 1859". HistoryLink. Retrieved February 21, 2022.

- ^ Josephy, The Nez Perce, p. 367

- ^ a b "Visitor information service book for the Deschutes National Forest : an abstract of literature, personal recollections, and interviews dealing with the Deschutes Forest". Oregon State University. 1969. Retrieved February 22, 2022.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k Paulus, Michael J. Jr. (February 26, 2008). "Walla Walla — Thumbnail History". HistoryLink. Retrieved February 20, 2022.

- ^ Paulus, Michael J. Jr. (August 18, 2010). "St. Patrick's Church is established in Walla Walla in 1859". HistoryLink. Retrieved February 27, 2022.

- ^ "Cayuse, Umatilla, Walla Walla Treaty" (PDF). Secretary of State of Washington. Retrieved February 21, 2022.

- ^ Gray, Claude M.; Gulick, Bill; Jones, Nard; Maxey, Dr. C. C.; Mcvay, Alfred; Orchard, Vance; Tooker, John (1953). Walla Walla Story - Illustrated Description Of The History And Resources Of The Valley They Liked So Well They Named It Twice. Walla Wall Chamber Of Commerce. ASIN B001SUTYPS.

- ^ Hamilton, Robin (April 29, 2019). "How Walla Walla Got Its Name". Walla Walla Union-Bulletin. Retrieved February 22, 2022.

- ^ "Brief History of CTUIR". Confederated Tribes of the Umatilla Indian Reservation. Retrieved February 22, 2022.

- ^ "George H. Abbott". truwe.sohs.org. Retrieved February 22, 2022.

- ^ a b c d Becker, Paula (March 31, 2006). "Walla Walla County – Thumbnail History". HistoryLink.

- ^ "The Mullan Road: A Real Northwest Passage". HistoryLink. November 5, 2009. Retrieved February 21, 2022.

- ^ Swergal, Edwin (December 14, 1952). "Captain Mullan sees it through". Spokesman-Review. Spokane, Washington. This Week section. p. 8.

- ^ Clark, Daniel (June 13, 2021). "Final work on historic Mullan Road through Walla Walla began 160 years ago". Walla Walla Union-Bulletin. Retrieved February 21, 2022.

- ^ a b c d e f Caldbick, John (June 1, 2013). "Washington Territorial Legislature incorporates City of Walla Walla on January 11, 1862". HistoryLink. Retrieved February 22, 2022.

- ^ "City of Walla Walla, Community Information". Ci.walla-walla.wa.us. Retrieved February 5, 2013.

- ^ Reed, Diane (April 29, 2019). "The Beginnings of Local and Regional Government". Walla Walla Union-Bulletin. Retrieved February 22, 2022.

- ^ Pickett, Susan (April 12, 1862). "Cousin of Marcus Whitman elected as Walla Walla's first mayor". Union-Bulletin.com. Retrieved February 22, 2022.

- ^ The new encyclopaedia Britannica. Inc Encyclopaedia Britannica (15 ed.). Chicago, Ill. 2010. ISBN 978-1-59339-837-8. OCLC 351325565.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) CS1 maint: others (link) - ^ a b c Reed, Diane (April 29, 2019). "Walla Walla and the Gold Rush". Walla Walla Union-Bulletin. Retrieved February 21, 2022.

- ^ Wilma, David (February 6, 2003). "Washington Statesman begins publication in Walla Walla on November 29, 1861. - HistoryLink.org". HistoryLink. Retrieved February 22, 2022.

- ^ "The Evening Statesman (Walla Walla, Wash.) 1903-1910". Library of Congress. Retrieved February 22, 2022.

- ^ Blethen, Rob (April 29, 2019). "The First Newspaper in Walla Walla". Walla Walla Union-Bulletin. Retrieved February 22, 2022.

- ^ Becker, Paula (October 17, 2007). "Baker Boyer Bank opens in Walla Walla on November 10, 1869". HistoryLink. Retrieved March 4, 2022.

- ^ Baker, W. W. (1923). "The Building of the Walla Walla & Columbia River Railroad". The Washington Historical Quarterly. 14 (1): 3–13. ISSN 0361-6223. JSTOR 40474681.

- ^ Bentley, Judy (April 5, 2016). Walking Washington's History: Ten Cities. University of Washington Press. ISBN 9780295806679.

- ^ White, Martha C. (March 2, 2022). "Oil soars as markets, consumers brace for more volatility". NBC News. Retrieved March 4, 2022.

- ^ Monahan, Susan (March 10, 2017). "A cut above the norm: Pioneer Meat Market on Main Street". Walla Walla Union-Bulletin. Retrieved March 13, 2022.

- ^ Bennett, Robert Allen (June 1, 1980). Walla Walla: Portrait of a Western Town, 1804-1898. Walla, Walla, WA: Pioneer Press Books. ISBN 0-936546-00-X. OCLC 6649756.

- ^ "Chapter 6". Kirkmanhousemuseum. Retrieved March 13, 2022.

- ^ a b Reed, Diane B. (2014). Legendary locals of Walla Walla, Washington. Charleston, South Carolina. ISBN 978-1-4671-0117-2. OCLC 866922900.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ^ Paulus, Michael J. Jr. (July 17, 2011). "Schwabacher Brothers open store in Walla Walla in the fall of 1860". HistoryLink. Retrieved March 6, 2022.

- ^ Paulus, Michael J. Jr. (August 24, 2008). "The Walla Walla Library Association is incorporated on January 20, 1865". HistoryLink. Retrieved March 6, 2022.

- ^ Monahan, Susan (February 12, 2018). "How did early Walla Wallans endure winter weather?". Walla Walla Union-Bulletin. Retrieved March 6, 2022.

- ^ a b Rizzo, Michael F. (2016). Washington beer : a heady history of Evergreen State brewing. Charleston, SC. ISBN 978-1-4671-1908-5. OCLC 940922344.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ^ a b c Reed, Diane B. (August 29, 2021). "Brewing up history: Beer has a long tradition in Walla Walla, more famous today for its wine industry". Walla Walla Union-Bulletin. ISSN 2154-6207. Retrieved March 6, 2022.

- ^ a b "Advertising Section" (PDF). Walla Walla Union-Bulletin. Vol. 1. December 13, 1861. p. 3. ISSN 2768-170X. Retrieved March 6, 2022.

- ^ a b c d McIntyre Walker, Catie (February 28, 2019). "Walla Walla, the way it used to be". Walla Walla Union-Bulletin. ISSN 2154-6207. Retrieved March 14, 2022.

- ^ Walter Nugent (December 18, 2007). Into the West: The Story of Its People. Knopf Doubleday Publishing. ISBN 9780307426420.

- ^ Hessel, Katherine (October 16, 2015). "Forgotten Chinatown In Walla Walla". KVEW. Retrieved March 6, 2022.

- ^ Chin, Art (March 2, 2012). "COMMENTARY: A Shadow of the Past: the Chinese experience in Walla Walla". Northwest Asian Weekly. Retrieved March 6, 2022.

- ^ Lange, Greg (April 23, 2000). "King, Eng Ah (1863-1915)". HistoryLink. Retrieved March 6, 2022.

- ^ Taylor, Quintard (1994). The forging of a black community : Seattle's Central District, from 1870 through the Civil Rights Era. Seattle. ISBN 978-0-295-80223-7. OCLC 930704151.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ^ a b c Freeman, Bob (February 7, 2021). "A few memorable tales of the history of the Washington State Penitentiary". Walla Walla Union-Bulletin. Retrieved March 6, 2022.

- ^ Plog, Kari (January 22, 2019). "Hell on Earth: A forgotten prison that predates McNeil Island". KNKX. Retrieved March 6, 2022.

- ^ Wilma, David (February 6, 2003). "First convicts occupy penitentiary at Walla Walla on May 11, 1887". HistoryLink. Retrieved March 6, 2022.

- ^ Wilma, David (February 6, 2003). "First convicts occupy penitentiary at Walla Walla on May 11, 1887". HistoryLink. Retrieved March 6, 2022.

- ^ Gibson, Elizabeth (April 26, 2009). "Nine die in escape attempt at Washington State Penitentiary in Walla Walla on February 12, 1934". HistoryLink. Retrieved March 6, 2022.

- ^ "10 CONVICTS FLEE PRISON BY TUNNEL; Felons in Washington State Escape Through Thirty-Foot Passage Dug Under Wall". The New York Times. November 4, 1955. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved March 6, 2022.

- ^ Shapiro, Nina (June 12, 2017). "5 of the most daring Washington state inmate escapes". The Seattle Times. Retrieved March 6, 2022.

- ^ Stammen, Emma (January 1, 2020). "Benevolent Feminism and the Gendering of Criminality: Historical and Ideological Constructions of US Women's Prisons". Scripps Senior Theses.

- ^ a b c Cipalla |, Rita (May 17, 2021). "Early Italians nurtured the Walla Walla onions from humble beginnings". L'Italo Americano. Retrieved March 6, 2022.

- ^ a b "Italians in Walla Walla Collection 1917-2018 - Archives West". Orbis Cascade Alliance. Retrieved March 6, 2022.

- ^ Cipalla, Rita (July 19, 2018). "Italian Immigrants: How They Helped Define the Wine Industry of Walla Walla". HistoryLink. Retrieved March 6, 2022.

- ^ Tuinstra, Rachel (April 21, 2007). "Walla Walla Sweet Onion now is the state vegetable". The Seattle Times. Retrieved March 6, 2022.

- ^ Johnson, Doug R. (1996). Adventism on the Northwestern frontier. Berrien Springs, Michigan: Oronoko Books. ISBN 1-883925-12-6. OCLC 35050746.

- ^ Paulus, Michael J. Jr. (May 12, 2009). "The first Seventh-day Adventist church in Walla Walla is organized on May 17, 1874". HistoryLink. Retrieved March 5, 2022.

- ^ Schillinger, William F.; Papendick, Robert I. (2008). "Then and Now: 125 Years of Dryland Wheat Farming in the Inland Pacific Northwest". Agronomy Journal. 100 (S3). doi:10.2134/agronj2007.0027c. ISSN 0002-1962.

- ^ Eveland, Annie Charnley (July 19, 2019). "Australia's Walla Walla celebrates 150th anniversary". Walla Walla Union-Bulletin. Retrieved March 5, 2022.

- ^ Marshall, Patrick (November 6, 2013). "College Place votes for incorporation on December 18, 1945". HistoryLink. Retrieved March 6, 2022.

- ^ Joyce-Bulay, Catie (May 12, 2021). "These Farmers Want You to Drink Your Hops and Eat Them Too". Atlas Obscura. Retrieved March 7, 2022.

- ^ Parker, Tom (September 1, 2002). Discovering Washington Wines: An Introduction to One of the Most Exciting Premium Wine Regions. Raconteurs Press. pp. 39–44, 92. ISBN 0-9719258-5-2.

- ^ a b Newspapers, Lee (August 20, 2018). "Walla Walla's first hops farm plans to grow the region's market". Wine and Craft Beverage News. Retrieved March 7, 2022.

- ^ Gibson, Elizabeth (March 7, 2006). "Walla Walla & Columbia River Railroad is completed from Wallula to Walla Walla on October 23, 1875". HistoryLink. Retrieved March 7, 2022.

- ^ a b Eveland, Annie Charnley (December 9, 2018). "New blog post features 1931 Mill Creek flood articles, photos". Walla Walla Union-Bulletin. Retrieved March 20, 2022.

- ^ Flom, Eric L. (December 23, 2005). "American Theater in Walla Walla opens on August 25, 1917". HistoryLink. Retrieved March 19, 2022.

- ^ Eveland, Annie Charnley (September 5, 2017). "Main Street's once-great Liberty Theater 100 years old". Walla Walla Union-Bulletin. Retrieved March 20, 2022.

- ^ "Downtown Walla Walla: Walla Walla, Washington". American Planning Association. Retrieved March 20, 2022.

- ^ "A history of the Bon Marche in downtown Seattle". KIRO-TV. January 30, 2020. Retrieved March 20, 2022.

- ^ Hillhouse, Vicki (January 7, 2020). "Macy's closing Walla Walla store". Walla Walla Union-Bulletin. Retrieved March 20, 2022.

- ^ Walker, Catie McIntyre (2018). Lost Restaurants of Walla Walla. Chicago: Arcadia Publishing Inc. ISBN 978-1-4396-6499-5. OCLC 1145596678.

- ^ Franklin, Robert R. (January 15, 2019). "Marcus Whitman Hotel". Society of Architectural Historians. Retrieved March 14, 2022.

- ^ Charnley Eveland, Annie (March 13, 2022). "Organizers: The 57th AAUW book sale is at Walla Walla Marcus Whitman Hotel most successful in its history". Walla Walla Union-Bulletin. ISSN 2154-6207. Retrieved March 14, 2022.

- ^ Freeman, Bob (2017). Personal stories of the Great Depression. Carroll B. Adams, Esther Whiteley, Harley Michaelis, Dorothy Hoffman, Donald D. Meiners, Emilio, Jr. Guglielmelli. [Walla Walla, Wash.] ISBN 978-1-5403-2168-8. OCLC 1013890485.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ^ "1940s Mill Creek Project helped divert water from downtown Walla Walla during historic 2020 flooding". KVEW-TV. February 13, 2020. Retrieved March 25, 2022.

- ^ "MANUFACTURING: Father of Peas". TIME. December 25, 1939. ISSN 0040-781X. Retrieved March 14, 2022.

- ^ Bennett, Robert Allen (1988). Walla Walla : a nice place to raise a family, 1920-1949. Walla Walla, WA: Pioneer Press Books. ISBN 0-936546-13-1. OCLC 21752307.

- ^ Rousso, Nick (October 14, 2021). "Grape Farming in Washington". HistoryLink. Retrieved March 26, 2022.

- ^ Gibson, Elizabeth (December 3, 2005). "Church Grape Juice Company field workers, in Kennewick, strike for higher wages on September 22, 1949". HistoryLink. Retrieved March 26, 2022.

- ^ "WA/OR - United States Earthquakes, 1936". Retrieved February 26, 2018.

- ^ Blecha, Peter (July 7, 2008). "Wine in Washington". HistoryLink. Retrieved March 26, 2022.

- ^ Paulus, Michael J. Jr. (February 6, 2008). "Walla Walla". HistoryLink. Retrieved March 26, 2022.

- ^ "Great American Main Street Award". Archived from the original on January 2, 2014. Retrieved January 1, 2014.

- ^ Bly, Laura (July 21, 2011). "The five best small towns in America". USA Today. Archived from the original on January 12, 2012.

- ^ "Best of the Road Walla Walla profile". Archived from the original on January 2, 2014. Retrieved January 1, 2014.

- ^ "2011 and 2012 Best of the Road contests". Archived from the original on December 5, 2013. Retrieved January 1, 2014.

- ^ "Agenda". Records.wallawallawa.gov:9443. October 17, 2012. Archived from the original on November 27, 2020. Retrieved August 6, 2022.

- ^ "Downtown Walla Walla: Walla Walla, Washington".

- ^ Joyce-Bulay, Catie (January 29, 2017). "For want of an ale: Change is a-brewing in Walla Walla". Walla Walla Union-Bulletin. Retrieved April 4, 2022.

- ^ Hillhouse, Vicki (September 29, 2019). "Business brewing as hops take root in Walla Walla Valley". Union-Bulletin.com. Retrieved April 4, 2022.

- ^ Hillhouse, Vicki (January 30, 2019). "Penitentiary announces hops and vineyard project". Walla Walla Union-Bulletin. Retrieved April 4, 2022.

- ^ O'Neill, Eilis (July 19, 2019). "Inmates will soon be growing wine grapes, hops inside the Washington State Penitentiary". npr. Retrieved April 4, 2022.

- ^ Maynes, Jedidiahh (February 6, 2020). "Brew crew: Local beer makers get a chance to shine in wine country". Walla Walla Union-Bulletin. Retrieved April 4, 2022.

- ^ a b "Holy Hometown Hero, Batman! It's Adam West Day In Walla Walla | Northwest Public Broadcasting". Northwest Public Broadcasting. September 14, 2018. Retrieved November 14, 2018.

- ^ "Celebrating the first official 'Adam West Day' in Walla Walla". NBC. September 19, 2017. Retrieved April 4, 2022.

- ^ Hillhouse, Vicki (August 23, 2019). "Adam West Day swoops back into Walla Walla". Walla Walla Union-Bulletin. Retrieved April 4, 2022.

- ^ Dinman, Emry (August 26, 2021). "Walla Walla celebrates Adam West, Batman actor and hometown superhero, for 4th year". Walla Walla Union-Bulletin. Retrieved April 4, 2022.

- ^ "Walla Walla's Adam West Day 2020 Officially Canceled". KATS. July 8, 2020. Retrieved April 4, 2022.

- ^ Dinmin, Emry (January 5, 2022). "Fundraiser to erect statue of Walla Walla's hometown hero, Batman actor Adam West, stalls". Walla Walla Union-Bulletin. Retrieved April 4, 2022.

- ^ Beyette, Beverly (December 23, 2004). "Here's to you, Walla Walla". The Seattle Times. Archived from the original on November 21, 2007. Retrieved April 2, 2007.

- ^ The Jolson Story (Video). Columbia Pictures. October 10, 1946.

- ^ Reed, Story and photos by Diane (April 8, 2019). "What's new in W2". Union-Bulletin.com. Retrieved February 20, 2020.

- ^ Adams, Cecil (March 20, 1981). "What are the lyrics to Walt Kelly's classic carol, "Deck Us All With Boston Charlie"?". The Straight Dope. Retrieved December 17, 2021.

- ^ Cash and Carry (Video). Columbia Pictures. September 3, 1937.

- ^ Transylvania 6-5000 (Video). Warner Bros. November 30, 1963.

- ^ A Mouse Divided (Video). Warner Bros. January 31, 1953.

- ^ The High and the Flighty (Video). Warner Bros. February 18, 1956.

- ^ This Is a Life? (Video). Warner Bros. July 9, 1955.

- ^ "U.S. Gazetteer files 2010". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved December 19, 2012.

- ^ "US Gazetteer files: 2010, 2000, and 1990". United States Census Bureau. February 12, 2011. Retrieved April 23, 2011.

- ^ "NowData – NOAA Online Weather Data". National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Retrieved February 17, 2012.

- ^ "U.S. Climate Normals Quick Access: Walla Walla Regional Airport, Washington". National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Archived from the original on September 6, 2023. Retrieved August 18, 2021.

- ^ "WMO Climate Normals for WALLA WALLA/CITY-COUNTY ARPT WA 1961–1990". National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Archived from the original on September 6, 2023. Retrieved September 6, 2023.

- ^ "Census of Population and Housing". Census.gov. Retrieved June 4, 2016.

- ^ a b c d e f g h "U.S. Census website". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved December 19, 2012.

- ^ Hillhouse, Vicki (February 1, 2014). "Viticultural area celebrates 30th year". Walla Walla Union-Bulletin. Archived from the original on April 5, 2015. Retrieved June 22, 2014.

- ^ Alexander, Rachel (July 30, 2017). "Nothing like a sweet, sweet onion from Walla Walla | The Spokesman-Review". Spokesman. Retrieved March 6, 2022.

- ^ "Meet Washington's sexiest vegetable: The Walla Walla Sweet Onion | Provided by Walla Walla Sweet Onions". The Seattle Times. June 25, 2021. Retrieved March 6, 2022.

- ^ "The Spokesman-Review Apr 6, 2007". April 5, 2007. Retrieved February 5, 2013.

- ^ Diaz, Alfred. "Walla Walla Doubles up on Farmers Markets". WW Union-Bulletin. Archived from the original on January 4, 2014. Retrieved January 3, 2014.

- ^ Barth, Jill; Clarke, Shana; Eschliman, Ziggy; Habibi, Tahiirah; Sanderson, Dynie (June 11, 2021). "Best Wine Region Winners (2020)". USA Today. Retrieved April 4, 2022.

- ^ Sanderson, Dynie; Barth, Jill; Clarke, Shana; Eschliman, Ziggy; Dubose, Larissa (July 6, 2021). "Best Wine Region Winners (2021)". USA Today. Retrieved April 4, 2022.

- ^ Walla Walla Valley Wine Alliance website - http://wallawallawine.com/

- ^ "2013 List of Washington State Wineries". Go Taste Wine, LLC. Archived from the original on December 25, 2013. Retrieved December 24, 2013.

- ^ Hollander, Catherine. "How Wine Growing in Walla Walla Supports the Economy". National Journal. Archived from the original on December 25, 2013. Retrieved December 24, 2013.

- ^ College Cellars website - http://www.collegecellars.com

- ^ Sean Sullivan's Washington Wine Report - http://www.wawinereport.com/2012/02/cabernet-sauvignon-production-down-28.html

- ^ "Washington Department of Corrections, WSP page". Archived from the original on June 13, 2011. Retrieved January 2, 2014.

- ^ "The Pioneer (Whitman College) article on the initial expansion". The Pioneer (Whitman College). Retrieved January 2, 2014.

- ^ "Seattle Times article, execution of Cal Cobrun Brown". The Seattle Times.

- ^ Clarridge, Christine; Kamb, Lewis (October 11, 2018). "Death penalty struck down by Washington Supreme Court, taking 8 men off death row". The Seattle Times. Retrieved October 15, 2018.

- ^ "Section 630.5, Procedures in Capital Murder". Retrieved April 27, 2006.

- ^ Maria L. La Ganga (February 11, 2014). "Washington state governor declares moratorium on death penalty". LA Times.

- ^ "Persons Executed Since 1904 in Washington State" (PDF). Washington State: Department of Corrections. Retrieved January 27, 2017.

- ^ Ponti, Crystal (November 21, 2021). "What Is Gary Ridgway's Life Like In Prison Today?". A&E. Retrieved March 6, 2022.

- ^ "US 12 - Nine Mile Hill to Frenchtown Vic - Build New Highway". Washington State Department of Transportation. December 2020. Retrieved March 18, 2021.

- ^ O'Boyle, Robert; Knutson, Kathleen (October 23, 1987). "WW's remoteness poses problem". Walla Walla Union-Bulletin. p. 2.

- ^ "Archived copy" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on October 19, 2016. Retrieved October 17, 2016.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link) - ^ "Tour of Walla Walla". Archived from the original on January 3, 2014. Retrieved January 2, 2014.

- ^ "Walla Walla Multisports webpage". Retrieved January 2, 2014.

- ^ "Our History". Walla Walla Symphony. Retrieved November 29, 2021.

- ^ "Walla Walla Chamber Music Festival Schedule". Archived from the original on January 4, 2014. Retrieved January 3, 2014.

- ^ "Past Performances". Retrieved January 1, 2014.

- ^ "History of the Powerhouse Theatre". Archived from the original on August 7, 2012. Retrieved January 1, 2014.

- ^ "History of the Little Theatre". Archived from the original on January 2, 2014. Retrieved January 1, 2014.

- ^ Cipolle, Alex V. (October 20, 2021). "In Washington, a Beloved Birthplace for Artistic Giants". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved March 26, 2022.

- ^ "Walla Walla Public Schools Website". Retrieved January 2, 2014.

- ^ "Aspen Institute, 2013 Aspen Prize". Retrieved January 2, 2014.

- ^ "Walla Walla-Sasayama Sister Cities Inc". Retrieved January 8, 2014.

- ^ "WW Union-Bulletin Article on the 2012 Exchanges". Walla Walla Union-Bulletin. Archived from the original on January 9, 2014. Retrieved January 8, 2014.

- ^ "Walla Walla, sister city Tamba-Sasayama benefit through connection". Walla Walla Union-Bulletin. Retrieved January 17, 2020.

- ^ "Former state Sen. Alex Deccio dies at 89". seattletimes.com. October 25, 2011. Retrieved September 19, 2021.

- ^ "Mourners honor Alex Deccio". nbcrightnow.com. November 3, 2011. Archived from the original on September 19, 2021. Retrieved September 19, 2021.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: bot: original URL status unknown (link)() - ^ "Alan W. Jones is Promoted". The Spokesman-Review. Spokane, WA. August 28, 1918. p. 2 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ Morelock, J. D. (1994). Generals of the Ardennes: American Leadership in the Battle of the Bulge. Washington, DC: National Defense University Press. p. 279. ISBN 978-0-16-042069-6 – via Internet Archive.

- ^ "404 Error". Archived from the original on November 19, 2009. Retrieved August 19, 2009.

{{cite web}}: Cite uses generic title (help) - ^ "Eric O'Flaherty". Baseball Reference. August 16, 2006. Retrieved April 11, 2015.

- ^ "Cher 👩💻🔥 Principal Software Engineer". cher.dev. Retrieved February 25, 2022.

Further reading

- MacGibbon, Elma (1904). Leaves of knowledge. Shaw & Borden Co. Available online through the Washington State Library's Classics in Washington History collection Elma MacGibbon's reminiscences of her travels in the United States starting in 1898, which were mainly in Oregon and Washington. Includes chapter "Walla Walla and southeastern Washington."

- Bennett, Robert A. Walla Walla: Portrait of a Western Town, 1804–1899. Walla Walla: Frontier Press Books, c. 1980.

- Gilbert, Frank T. Historic Sketches: Walla Walla, Columbia and Garfield Counties, Washington Territory. Portland, Oregon: A.G. Walling Printing