Central Italy

Central Italy

Italia centrale | |

|---|---|

| |

| Country | Italy |

| Regions | |

| Area | |

• Total | 58,052 km2 (22,414 sq mi) |

| Population | |

• Estimate (2023 est.) | 11,680,843 |

| Languages | |

| – Official language | Italian |

| – Other common languages | |

Central Italy (Template:Lang-it or just Centro) is one of the five official statistical regions of Italy used by the National Institute of Statistics (ISTAT), a first-level NUTS region, and a European Parliament constituency.

Regions

Central Italy encompasses four of the country's 20 regions:

The southernmost and easternmost parts of Lazio (Sora, Cassino, Gaeta, Cittaducale, Formia, and Amatrice districts) are often included in Southern Italy (the so-called Mezzogiorno) for cultural and historical reasons, since they were once part of the Kingdom of the Two Sicilies and southern Italian dialects are spoken.

As a geographical region, however, central Italy may also include the regions of Abruzzo and Molise,[2][3][4] which are otherwise considered part of Southern Italy for socio-cultural, linguistic and historical reasons.

Geography

It is crossed by the northern and central Apennines and is washed by the Adriatic Sea to the east, by the Tyrrhenian Sea and the Ligurian Sea to the west. The main rivers of this portion of the territory are the Arno and the Tiber with their tributaries (e.g. Aniene), and the Liri-Garigliano. The most important lakes are Lake Trasimeno, Lake Montedoglio, Lake Bolsena, Lake Bracciano, Lake Vico, Lake Albano and Lake Nemi. From an altimetric point of view, central Italy has a predominantly hilly territory (68.9%). The mountainous and flat areas are equivalent to 26.9% and 4.2% of the territorial distribution respectively.

History

For centuries, before the unification of Italy, which occurred in 1861, central Italy was divided into two states, the Papal States and the Grand Duchy of Tuscany.

Papal States

The Papal States, officially the State of the Church, were a series of territories in the Italian Peninsula under the direct sovereign rule of the pope from 756 until 1870.[5] They were among the major states of Italy from the 8th century until the unification of Italy, between 1859 and 1870.

The state had its origins in the rise of Christianity throughout Italy, and with it the rising influence of the Christian Church. By the mid-8th century, with the decline of the Byzantine Empire in Italy, the Papacy became effectively sovereign. Several Christian rulers, including the Frankish kings Charlemagne and Pepin the Short, further donated lands to be governed by the Church.[6] During the Renaissance, the papal territory expanded greatly and the pope became one of Italy's most important secular rulers as well as the head of the Church. At their zenith, the Papal States covered most of the modern Italian regions of Lazio (which includes Rome), Marche, Umbria and Romagna, and portions of Emilia. These holdings were considered to be a manifestation of the temporal power of the pope, as opposed to his ecclesiastical primacy.

By 1861, much of the Papal States' territory had been conquered by the Kingdom of Italy. Only Lazio, including Rome, remained under the pope's temporal control. In 1870, the pope lost Lazio and Rome and had no physical territory at all, except the Leonine City of Rome, which the new Italian state did not occupy militarily, despite annexation of Lazio. In 1929, the Italian fascist leader Benito Mussolini, the head of the Italian government, ended the "Prisoner in the Vatican" problem involving a unified Italy and the Holy See by negotiating the Lateran Treaty, signed by the two parties. This treaty recognized the sovereignty of the Holy See over a newly created international territorial entity, a city-state within Rome limited to a token territory which became the Vatican City.

Grand Duchy of Tuscany

The Grand Duchy of Tuscany was an Italian monarchy that existed, with interruptions, from 1569 to 1860, replacing the Republic of Florence.[7] The grand duchy's capital was Florence. In the 19th century the population of the Grand Duchy was about 1,815,000 inhabitants.[8]

Having brought nearly all Tuscany under his control after conquering the Republic of Siena, Cosimo I de' Medici, was elevated by a papal bull of Pope Pius V to Grand Duke of Tuscany on August 27, 1569.[9][10] The Grand Duchy was ruled by the House of Medici until the extinction of its senior branch in 1737. While not as internationally renowned as the old republic, the grand duchy thrived under the Medici and it bore witness to unprecedented economic and military success under Cosimo I and his sons, until the reign of Ferdinando II, which saw the beginning of the state's long economic decline. It peaked under Cosimo III.[11]

Francis Stephen of Lorraine, a cognatic descendant of the Medici, succeeded the family and ascended the throne of his Medicean ancestors. Tuscany was governed by a viceroy, Marc de Beauvau-Craon, for his entire rule. His descendants ruled, and resided in, the grand duchy until its end in 1859, barring one interruption, when Napoleon Bonaparte gave Tuscany to the House of Bourbon-Parma (Kingdom of Etruria, 1801–1807), then annexed it directly to the First French Empire. Following the collapse of the Napoleonic system in 1814, the grand duchy was restored. The United Provinces of Central Italy, a client state of the Kingdom of Sardinia, annexed Tuscany in 1859. Tuscany was formally annexed to Sardinia in 1860, as a part of the unification of Italy, following a landslide referendum, in which 95% of voters approved.[12][13]

Demography

In 2023, the population resident in central Italy amounts to 11,680,843 inhabitants.[1]

Regions

| Region | Capital | Inhabitants |

|---|---|---|

| Rome | 5,703,289 | |

| Ancona | 1,478,881 | |

| Florence | 3,647,054 | |

| Perugia | 851,619 |

Most populous municipalities

Below is the list of the population residing in 2023 in municipalities with more than 50,000 inhabitants.[1]

| # | Municipality | Region | Inhabitants |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Rome | 2,746,639 | |

| 2 | Florence | 360,444 | |

| 3 | Prato | 195,906 | |

| 4 | Perugia | 161,375 | |

| 5 | Livorno | 152,138 | |

| 6 | Latina | 127,321 | |

| 7 | Terni | 106,121 | |

| 8 | Ancona | 98,292 | |

| 9 | Arezzo | 96,176 | |

| 10 | Pesaro | 95,352 | |

| 11 | Guidonia Montecelio | 89,191 | |

| 12 | Pistoia | 89,000 | |

| 13 | Pisa | 88,726 | |

| 14 | Lucca | 88,724 | |

| 15 | Fiumicino | 81,855 | |

| 16 | Grosseto | 81,154 | |

| 17 | Aprilia | 74,240 | |

| 18 | Massa | 65,933 | |

| 19 | Viterbo | 65,927 | |

| 20 | Pomezia | 64,246 | |

| 21 | Viareggio | 60,416 | |

| 22 | Carrara | 59,786 | |

| 23 | Fano | 59,732 | |

| 24 | Anzio | 58,946 | |

| 25 | Foligno | 55,068 | |

| 26 | Tivoli | 54,908 | |

| 27 | Siena | 52,657 | |

| 28 | Velletri | 52,542 | |

| 29 | Civitavecchia | 51,678 |

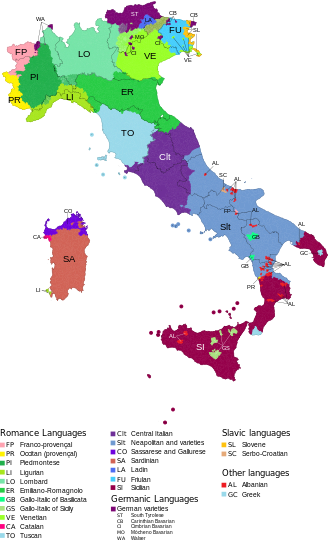

Languages

Central Italy is dominated by Central Italian and Tuscan dialect. Other languages spoken are Gallo-Piceno ("Gallo-Italic Marche" or "Gaul-Marche"), a Gallo-Italic language spoken in the province of Pesaro and Urbino and in the northern part of the province of Ancona, Marche region,[14] and Neapolitan, spoken in southern Lazio and in southern Marche as well as eastern fringes of Umbria.

Central Italian refers to the dialects of Italo-Romance spoken in the so-called Area Mediana, which covers a swathe of the central Italian peninsula. Area Mediana is also used in a narrower sense to describe the southern part, in which case the northern one may be referred to as the Area Perimediana, a distinction that will be made throughout this article. The two areas are split along a line running approximately from Rome in the southwest to Ancona in the northeast.[15] In the early Middle Ages, Central Italian extended north into Romagna and covered all of modern-day Lazio, Abruzzo, and Molise. Since then, however, the dialects spoken in those areas have been assimilated into Gallo-Italic and Southern Italo-Romance respectively.[16] In addition, the dialect of Rome has undergone considerable Tuscanization from the fifteenth century onwards, such that it has lost many of its Central Italian features.[17][18]

Tuscan dialect is a set of Italo-Dalmatian varieties of Romance spoken in Tuscany, Corsica, and Sardinia. Standard Italian is based on Tuscan, specifically on its Florentine dialect, and it became the language of culture throughout Italy[19] due to the prestige of the works by Dante Alighieri, Petrarch, Giovanni Boccaccio, Niccolò Machiavelli, and Francesco Guicciardini. It would later become the official language of all the Italian states and of the Kingdom of Italy when it was formed. Corsican on the island of Corsica and the Corso-Sardinian transitional varieties spoken in northern Sardinia (Gallurese and Sassarese) are classified by scholars as a direct offshoot from medieval Tuscan,[20] even though they now constitute a distinct linguistic group.

Politics

Marche, Tuscany, and Umbria, together with Emilia-Romagna, are considered to be the most left-leaning regions in Italy, and together are also referred to as the "Red Belt".[21][22][23][24]

Economy

The gross domestic product (GDP) of the region was 380.9 billion euros in 2018, accounting for 21.6% of Italy's economic output. The GDP per capita adjusted for purchasing power was 31,500 euros, or 105% of the EU27 average the same year.[25]

Culture

The regions of central Italy were exposed to different historical influences, which were due to the peoples that settled there, such as the Celts, the Etruscans, the North Picenes, the South Picene, the Umbri, the Latins, the Romans, the Byzantines and the Lombards. Some of its woodlands and mountains are preserved in several National Parks; a major example is the Abruzzo, Lazio and Molise National Park, located in the Abruzzo region, with smaller parts in Lazio and Molise. It is the oldest in the Apennine Mountains, and the second oldest in Italy, with an important role in the preservation of endemic species such as the Italian wolf, Abruzzo chamois and Marsican brown bear.

Central Italy has many major tourist attractions, many of which are protected by UNESCO. Central Italy is possibly the most visited in Italy and contains many popular attractions as well as sought-after landscapes. Rome boasts the remaining wonders of the Roman Empire and some of the world's best-known landmarks such as the Colosseum. Florence, regarded as the birthplace of the Italian Renaissance, is Tuscany's most visited city, whereas nearby cities like Siena, Pisa, Arezzo and Lucca also have rich cultural heritage. Umbria's population is small but it has many important cities such as Perugia and Assisi. For similar reasons, Lazio and Tuscany are some of Italy's most visited regions and the main targets for Ecotourism. This area is known for its picturesque landscapes and attracts tourists from all over the world, including Italy itself. Pristine landscapes serve as one of the primary motivators for tourists to visit central Italy, although there are others, such as a rich history of art.

Roman cuisine comes from the Italian city of Rome. It features fresh, seasonal and simply-prepared ingredients from the Roman Campagna.[26] These include peas, globe artichokes and fava beans, shellfish, milk-fed lamb and goat, and cheeses such as Pecorino Romano and ricotta.[27] Olive oil is used mostly to dress raw vegetables, while strutto (pork lard) and fat from prosciutto are preferred for frying.[26] The most popular sweets in Rome are small individual pastries called pasticcini, gelato (ice cream) and handmade chocolates and candies.[28] Special dishes are often reserved for different days of the week; for example, gnocchi is eaten on Thursdays, baccalà (salted cod) on Fridays, and trippa on Saturdays.

See also

- National Institute of Statistics (Italy)

- NUTS statistical regions of Italy

- Italian NUTS level 1 regions:

- Northern Italy

- Southern Italy

References

- ^ a b c "Bilancio demografico e popolazione residente per sesso al 30 giugno 2023" (in Italian). Retrieved 25 September 2023.

- ^ Source: Touring Club Italiano (TCI), "Atlante stradale d'Italia". 1999–2000 TCI Atlas. ISBN 88-365-1115-5 (Northern Italy volume) – ISBN 88-365-1116-3 (Central Italy volume) – ISBN 88-365-1117-1 (Southern Italy volume)

- ^ Source: De Agostini, "Atlante Geografico Metodico". ISBN 88-415-6753-8

- ^ Source: Enciclopedia Italiana "Treccani"

- ^ "Papal States". Encyclopædia Britannica. 30 April 2020. Archived from the original on 5 October 2021. Retrieved 11 August 2021.

- ^ "Papal States | historical region, Italy | Britannica". www.britannica.com. Archived from the original on 2021-11-15. Retrieved 2021-11-21.

- ^ Strathern, Paul (2003). The Medici: Godfathers of the Renaissance. London: Vintage. ISBN 978-0-09-952297-3. pp. 315–321

- ^ Ministry of Agriculture, Industry and Commerce (1862). Popolazione censimento degli antichi Stati sardi (1. gennaio 1858) e censimenti di Lombardia, di Parma e di Modena (1857–1858) pubblicati per cura del Ministero d'agricoltura, industria e commercio: Relazione generale con una introduzione storica sopra i censimenti delle popolazioni italiane dai tempi antichi sino all'anno 1860. 1.1 (in Italian). Stamperia Reale.

- ^ "bolla papale di Pio V". archeologiavocidalpassato (in Italian). Retrieved 2021-02-10.

- ^ "Cosimo I | duke of Florence and Tuscany [1519–1574]". Encyclopedia Britannica. Retrieved 2021-02-10.

- ^ "COSIMO III de' Medici, granduca di Toscana". Dizionario Biografico (in Italian). Retrieved 2020-04-25.

- ^ François Velde (July 4, 2005). "The Grand-Duchy of Tuscany". heraldica.org. Retrieved 2009-08-19.

- ^ Acton, p. 254

- ^ Francesco Avolio, Dialetti, in Enciclopedia Treccani, 2010.

- ^ Loporcaro, Michele & Paciaroni, Tania. 2016. The dialects of central Italy. In Ledgeway, Adam & Maiden, Martin (eds.), The Oxford guide to the Romance languages, 228–245. Oxford University Press, p. 228

- ^ Loporcaro & Panciani 2016: 229–230

- ^ Vignuzzi, Ugo. 1997. Lazio, Umbria, and the Marche. In Maiden, Martin & Parry, Mair (eds.), The dialects of Italy, London: Routledge, pp. 312-317

- ^ Loporcaro & Panciani 2016, pp. 229-233

- ^ "storia della lingua in "Enciclopedia dell'Italiano"". www.treccani.it.

- ^ Harris, Martin; Vincent, Nigel (1997). Romance Languages. London: Routlegde. ISBN 0-415-16417-6.

- ^ "'Italians first': how the populist right became Italy's dominant force". The Guardian. 1 December 2018.

- ^ Roy Palmer Domenico (2002). The Regions of Italy: A Reference Guide to History and Culture. p. 313. ISBN 9780313307331.

- ^ "Italy's EU election results by region: Who won where?". The Local. 27 May 2019.

- ^ Publications, Europa Europa (2002). Western Europe 2003. p. 362. ISBN 9781857431520.

- ^ "Regional GDP per capita ranged from 30% to 263% of the EU average in 2018". Eurostat.

- ^ a b Boni (1930), pg. 13.

- ^ Boni (1930), pg. 14

- ^ Eats, Serious. "Gina DePalma's Guide To Rome Sweets". sweets.seriouseats.com. Retrieved 2017-11-14.