Richard Helms

This article has multiple issues. Please help improve it or discuss these issues on the talk page. (Learn how and when to remove these messages)

|

Richard Helms | |

|---|---|

Official portrait c. 1966–72 | |

| United States Ambassador to Iran | |

| In office April 5, 1973 – December 27, 1976 | |

| President | Richard Nixon Gerald Ford |

| Preceded by | Joseph S. Farland |

| Succeeded by | William H. Sullivan |

| 8th Director of Central Intelligence | |

| In office June 30, 1966 – February 2, 1973 | |

| President | Lyndon B. Johnson Richard Nixon |

| Deputy | Rufus Taylor Robert E. Cushman Jr. Vernon A. Walters |

| Preceded by | William Raborn |

| Succeeded by | James R. Schlesinger |

| 7th Deputy Director of Central Intelligence | |

| In office April 28, 1965 – June 30, 1966 | |

| President | Lyndon B. Johnson |

| Preceded by | Marshall Carter |

| Succeeded by | Rufus Taylor |

| Deputy Director of Central Intelligence for Plans | |

| In office February 17, 1962 – April 28, 1965 | |

| President | John F. Kennedy Lyndon B. Johnson |

| Preceded by | Richard M. Bissell Jr. |

| Succeeded by | Desmond Fitzgerald |

| Personal details | |

| Born | Richard McGarrah Helms March 30, 1913 St. Davids, Pennsylvania, U.S. |

| Died | October 23, 2002 (aged 89) Washington, D.C., U.S. |

| Resting place | Arlington National Cemetery |

| Relations | Gates W. McGarrah (grandfather) |

| Education | Williams College (BA) |

| Military service | |

| Allegiance | |

| Branch/service | |

| Years of service | 1942–1946 |

| Battles/wars | World War II |

Richard McGarrah Helms (March 30, 1913 – October 23, 2002) was an American government official and diplomat who served as Director of Central Intelligence (DCI) from 1966 to 1973. Helms began intelligence work with the Office of Strategic Services during World War II. Following the 1947 creation of the Central Intelligence Agency (CIA), he rose in its ranks during the presidencies of Truman, Eisenhower and Kennedy. Helms then was DCI under Presidents Johnson and Nixon,[1] yielding to James R. Schlesinger in early 1973.

As a spy, Helms highly valued information gathering (favoring the interpersonal, but including the technical, obtained by espionage or from published media) and its analysis while prizing counterintelligence. Although a participant in planning such activities, Helms remained a skeptic about covert and paramilitary operations. While working as the DCI, Helms managed the agency following the lead of his predecessor John McCone. In 1977, as a result of earlier covert operations in Chile, Helms became the only DCI convicted of misleading Congress. Helms's last post in government service was Ambassador to Iran from April 1973 to December 1976. Besides this Helms was a key witness before the Senate during its investigation of the CIA by the Church Committee in the mid-1970s, 1975 being called the "Year of Intelligence".[2][full citation needed] This investigation was hampered severely by Helms having ordered the destruction of all files related to the CIA's mind control program in 1973.[3]

Early career

Helms was born and raised in Pennsylvania. He attended Institut Le Rosey in Switzerland. At this high school in Europe, Helms learned French and German. He returned and graduated from Williams College in Massachusetts. He then worked as a journalist in Europe, and for the Indianapolis Times. Married when America entered World War II, he joined the Navy. Then Helms was recruited by the OSS, for whom he later served in Europe. Helms began his spy career by serving in the war-time Office of Strategic Services (OSS). Following the Allied victory, Helms was stationed in Germany[1] serving under Allen Dulles and Frank Wisner.[citation needed] In late 1945, President Truman terminated the OSS. Back in Washington, Helms continued similar intelligence work as part of the Strategic Services Unit (SSU), later called the Office of Special Operations (OSO). During this period, Helms focused on espionage in central Europe at the start of the Cold War and took part in the vetting of the German Gehlen spy organization. The OSO was incorporated into the Central Intelligence Agency (CIA) when it was founded in 1947.

In 1950 Truman appointed General Walter Bedell Smith as the fourth director of Central Intelligence (DCI). The CIA became established institutionally within the United States Intelligence Community. DCI Smith merged the OSO (being mainly espionage, and newly led by Helms) and the rapidly expanding Office of Policy Coordination under Wisner (covert operations) to form a new unit to be managed by the deputy director for plans (DDP). Wisner led the Directorate for Plans from 1952 to 1958, with Helms as his Chief of Operations.

In 1953 Dulles became the fifth DCI under President Eisenhower. John Foster Dulles, Dulles' brother, was Eisenhower's Secretary of State. Under the DDP Helms was specifically tasked in the defense of the agency against the threatened attack by Senator Joseph McCarthy, and also in the development of "truth serum" and other "mind control" drugs per the CIA's controversial Project MKUltra. From Washington, Helms oversaw the Berlin Tunnel, the 1953–1954 espionage operation which later made newspaper headlines. Regarding CIA activity, Helms considered information obtained by espionage to be more beneficial in the long run than the more strategically risky work involved in covert operations, which could backfire politically. Under his superior and mentor, the DDP Wisner, the CIA marshaled such covert operations, which resulted in regime change in Iran in 1953 and Guatemala in 1954 and interference in the Congo in 1960. During the crises in Suez and Hungary in 1956 the DDP Wisner became distraught by the disloyalty of allies and the loss of a precious cold-war opportunity. Wisner left in 1958. Passing over Helms, DCI Dulles appointed Richard Bissell as the new DDP, who had managed the U-2 spy plane.

During the Kennedy presidency, Dulles selected Helms to testify before Congress on Soviet-made forgeries. Following the 1961 Bay of Pigs fiasco, President Kennedy appointed John McCone as the new DCI, and Helms then became the DDP. Helms was assigned to manage the CIA's role in Kennedy's multi-agency effort to dislodge Castro. During the Cuban Missile Crisis, while McCone sat with the president and his cabinet at the White House, Helms in the background supported McCone's significant contributions to the strategic discussions. After the 1963 coup in South Vietnam, Helms was privy to Kennedy's anguish over the killing of President Diem. Three weeks later Kennedy was assassinated. Helms eventually worked to manage the CIA's complicated response during its subsequent investigation by the Warren Commission.[4]

Johnson presidency

In June 1966, Helms was appointed director of Central Intelligence. At the White House later that month, Helm was sworn in during a ceremony arranged by President Lyndon Baines Johnson.[5] In April of the prior year, John McCone resigned as DCI. Johnson then had appointed Admiral William Raborn, well regarded for his work on the submarine-launched Polaris missile, as the new DCI (1965–1966). Johnson chose Helms to serve as Deputy Director of Central Intelligence (DDCI). Raborn and Helms soon journeyed to the LBJ Ranch in Texas. Raborn did not fit well into the institutional complexities at the CIA, with its specialized intellectual culture. He resigned in 1966.[6][7]

As DCI, Helms served under President Johnson during the second half of his administration, then continued in this post until 1973, through President Nixon's first term.[8] At CIA Helms was its first Director to 'rise through the ranks'.[9]

The Vietnam War became the key issue during the Johnson years.[10] The CIA was fully engaged in political-military affairs in Southeast Asia, both getting intelligence information and for overt and covert field operations. The CIA, for example, organized an armed force of minority Hmong in Laos, and in Vietnam of rural counterinsurgency forces, and of minority Montagnards in the highlands. Further, the CIA became actively involved in South Vietnamese politics, especially after Diem. "One of the CIA's jobs was to coax a genuine South Vietnamese government into being."[11][12] Helms traveled to Vietnam twice,[13] and with President Johnson to Guam.[14]

Vietnam: Estimates

In 1966, Helms as the new DCI inherited a CIA "fully engaged in the policy debates surrounding Vietnam." The CIA had formed "a view on policy but [was] expected to contribute impartially to the debate all the same."[15] American intelligence agents had a relatively long history in Vietnam, dating back to OSS contacts with the communist-led resistance to Japanese occupation forces during World War II.[16] In 1953 the CIA's first annual National Intelligence Estimate on Vietnam reported that French prospects may "deteriorate very rapidly".[17] After French withdrawal in 1954, CIA officers including Lt. Col. Edward Lansdale assisted the new President Ngo Dinh Diem in his efforts to reconstitute an independent government in the south: the Republic of Viet Nam.[18][19]

Nonetheless, CIA reports did not present an optimistic appraisal of Diem's future. Many of its analysts reluctantly understood that, in the anti-colonialist and nationalist context then prevailing, a favorable outcome was more likely for the new communist regime in the north under its long-term party leader Ho Chi Minh, who was widely admired as a Vietnamese patriot. A 1954 report by the CIA qualifiedly stated that if nationwide elections scheduled for 1956 by the recent Geneva Accords were held, Ho's party "the Viet Minh will almost certainly win."[20][21][22] The nationwide elections were avoided. According to 1959 reports, the CIA saw Diem as "the best anticommunist bet" if he undertook reforms, but also stated that Diem consistently avoided reform.[23][24]

As the political situation progressed during the 1960s and American involvement grew, subsequent CIA reports crafted by its analysts continued to trend pessimistic regarding the prospects for South Vietnam.[25] "Vietnam may have been a policy failure. It was not an intelligence failure."[26] The CIA eventually became sharply divided over the issue. Those active in CIA operations in Vietnam, e.g., Lucien Conein, and William Colby, adopted a robust optimism regarding the outcome of their contentious projects. Teamwork in dangerous circumstances, and social cohesion among such operatives in the field, worked to reinforce and intensify their positive views.[27][28]

"At no time was the institutional dichotomy between the operational and analytic components more stark."[29][30] Helms later described the predicament at CIA as follows.

From the outset, the intelligence directorate and the Office of National Estimates held a pessimistic view of the military developments. The operations personnel—going full blast ... in South Vietnam—remained convinced the war could be won. Without this conviction, the operators could not have continued their difficult face-to-face work with the South Vietnamese, whose lives were often at risk. In Washington, I felt like a circus rider standing astride two horses, each for the best of reasons going its own way.[31][32]

Negative news would prove to be highly unwelcome at the Johnson White House. "After each setback the CIA would gain little by saying 'I told you so' or by continuing to emphasize the futility of the war," author Ranelagh writes about the CIA predicament.[33] In part it was DCI McCone's worrisome reports and unwelcome views about Vietnam that led to his exclusion from President Johnson's inner circle; consequently, McCone resigned in 1965. Helms remembered that McCone left the CIA because "he was dissatisfied with his relation with President Johnson. He didn't get to see him enough, and he didn't feel that he had any impact."[34][35]

Helms' institutional memory probably contested for influence over his own decisions as DCI when he later served under Johnson. According to CIA intelligence officer Ray Cline, "Up to about 1965/66, estimates were not seriously biased in any direction." As American political commitment to Vietnam surged under Johnson, however, "the pressure to give the right answer came along," stated Cline. "I felt increasing pressure to say the war was winnable."[36]

Laos: "secret war"

The "second Geneva Convention" of 1962 settled de jure the neutrality of the Kingdom of Laos, obtaining commitments from both the Soviets and the Americans. Nonetheless, such a neutral status quo in Laos soon became threatened de facto, e.g., by North Vietnamese (NVN) armed support for the communist Pathet Lao. The CIA in 1963 was tasked to mount an armed defense of the "neutrality" of the Kingdom. Helms then served as DDP and thus directed the overall effort. It was a secret war because both NVN and CIA were in violation of Geneva's 1962 terms.[38][39]

Thereafter during the 1960s the CIA accomplished this mission largely by training and arming native tribal forces, primarily those called the Hmong.[40] Helms called it "the war we won". At most several hundred CIA personnel were involved, at a small fraction of the cost of the Vietnam War. Despite prior criticism of the CIA's abilities due to the 1961 Bay of Pigs disaster in Cuba, here the CIA for years successfully managed a large-scale paramilitary operation. At the height of the Vietnam War, much of royal Laos remained functionally neutral, although over its southeast borderlands ran the contested Ho Chi Minh trail. The CIA operation fielded as many as 30,000 Hmong soldiers under their leader Vang Pao, while also supporting 250,000 mostly Hmong people in the hills. Consequently, more than 80,000 NVN troops were "tied down" in Laos.[41][42][43][44]

At the time of Nixon's Vietnamization policy, CIA concern arose over sustaining the covert nature of the secret war. In 1970 Helms decided "to transfer the budgetary allocations for operations in Laos from the CIA to the Defense Department."[45][46] William Colby, then a key American figure in Southeast Asia and later DCI, comments that "a large-scale paramilitary operation does not fit the secret budget and policy procedures of CIA."[47]

About Laos, however, Helms wrote that "I will always call it the war we won."[48] In 1966, the CIA had termed it "an exemplary success story".[49] Colby concurred.[50] Senator Stuart Symington, after a 1967 visit to the CIA chief of station in Vientiane, the Laotian capital, reportedly called it "a sensible way to fight a war."[51] Yet others disagreed, and the 'secret war' would later draw frequent political attacks.[52][53] Author Weiner criticizes the imperious insertion of American power, and the ultimate abandonment of America's Hmong allies in 1975.[54][55] Other problems arose because of the Hmong's practice of harvesting poppies.[56][57][58]

Due to political developments, the war ultimately ended badly. Helms acknowledges that after President Nixon, through his agent Kissinger, negotiated in Paris to end the Vietnam war in 1973, America failed to continue supporting its allies and "abdicated its role in Southeast Asia." Laos was given up and the Hmong were left in a desperate situation. Helms references that eventually 450,000 Laotians including 200,000 Hmong emigrated to the United States.[59][60][61]

While this Laotian struggle continued on the borderlands of the Vietnam War, DCI Helms was blindsided when several senators began to complain that they had been kept in the dark about the "CIA's secret war" in Laos. Helms recalls that three presidents, Kennedy, Johnson, and Nixon, had each approved the covert operation, the "secret war", and that 50 senators had been briefed on its progress, e.g., Senator Symington had twice visited Laos.[62][63] Helms elaborates on the turnabout:

In 1970, it came as a jolt when, with a group of senators, Senator Stuart Symington publicly expressed his "surprise, shock and anger" at what he and the others claimed was their "recent discovery" of "CIA's secret war" in Laos. At the time I could not understand the reason for this about-face. Nor have I since been able to fathom it.[64][65]

Israel: Six Day War

Liaison with Israeli intelligence was managed by James Jesus Angleton of CIA counterintelligence from 1953 to 1974.[66][67] For example, the Israelis quickly provided the CIA with the Russian text of Khrushchev's Secret Speech of 1956 which severely criticized the deceased Soviet dictator Joseph Stalin.[68] In August 1966 Mossad had arranged for Israeli acquisition of a Soviet MiG-21 fighter from a disaffected Iraqi pilot. Mossad's Meir Amit later came to Washington to tell DCI Helms that Israel would loan America the plane, with its up-until-now secret technology, to find out how it flew.[69] At a May 1967 NSC meeting Helms voiced praise for Israel's military preparedness, and argued that from the captured MiG-21 the Israelis "had learned their lessons well".[70][71]

In 1967, CIA analysis addressed the possibility of an armed conflict between Israel and neighboring Arab states, predicting that "the Israelis would win a war within a week to ten days."[72][73][74] Israel "could defeat any combination of Arab forces in relatively short order" with the time required depending on "who struck first" and circumstances.[75] Yet CIA's pro-Israel prediction was challenged by Arthur Goldberg, the American ambassador to the United Nations and Johnson loyalist.[76] Although Israel then had requested "additional military aid" Helms opines that here Israel wanted to control international expectations prior to the outbreak of war.[77]

As Arab war threats mounted, President Johnson asked Helms about Israel's chances and Helms stuck with his agency's predictions. At a meeting of his top advisors Johnson then asked who agreed with the CIA estimate and all assented.[78] "The temptation for Helms to hedge his bet must have been enormous".[79] After all, opinions were divided, e.g., Soviet intelligence thought the Arabs would win and were "stunned" at the Israeli victory.[80] Admiral Stansfield Turner (DCI 1977–1981) wrote that "Helms claimed that the high point of his career was the Agency's accurate prediction in 1967." Helms believed it had kept America out of the conflict. Also, it led to his entry within the inner circle of the Johnson administration, the regular 'Tuesday lunch' with the President.[81]

In the event, Israel decisively defeated its neighborhood enemies and prevailed in the determinative Six Day war of June 1967. Four days before the sudden launch of that war, "a senior Israeli official" had privately visited Helms in his office and hinted that such a preemptive decision was imminent. Helms then had passed the information to President Johnson.[82][83][84] The conflict reified America's "emotional sympathy" for Israel. Following the war, America dropped its careful balancing act between the belligerents and moved to a position in support of Israel, eventually supplanting France as Israel's chief military supplier.[85][86]

In the afternoon of the third day of the war, the American SIGINT spy ship USS Liberty, outfitted by the NSA, was attacked by Israeli warplanes and torpedo boats in international waters north of Sinai. This U.S. Navy ship was severely damaged with loss of life.[87][88] The Israelis quickly notified the Americans and later explained that they "had mistaken the Liberty (455 feet long) for the Egyptian coastal steamer El Quseir (275 feet long). The US government formally accepted the apology and the explanation."[89] Some continue to accept this position.[90][91] Yet "scholars and military experts," according to author Thomas Powers, state that "the hard question is not whether the attack was deliberate but why the Israelis thought it necessary."[92][93][94] In his memoirs A Look Over My Shoulder, Helms expressed his bewilderment as to how and why the USS Liberty was attacked: "One of the most disturbing incidents in the six days came in the morning of June 8 when the Pentagon flashed a message that the U.S.S. Liberty, an unarmed U.S. Navy communications ship, was under attack in the Mediterranean, and that American fighters had been scrambled to defend the ship. The following urgent reports showed that Israeli jet fighters and torpedo reports had launched the attack. The seriously damaged Liberty remained afloat, with thirty-four dead and more than a hundred wounded members of the crew. Israeli authorities subsequently apologized for the accident, but few in Washington could believe that the ship had not been identified as an American naval vessel. Later, an interim intelligence memorandum concluded the attack was a mistake and "not made in malice against the U.S." When additional evidence was available, more doubt was raised. This prompted my deputy, Admiral Rufus Taylor, to write me his view of the incident. "To me, this picture thus far presents the distinct possibility that the Israelis knew that Liberty might be their target and attacked anyway, either through confusion in Command and Control or through deliberate disregard of instructions on the part of subordinates."...I had no role in the board of inquiry that followed, or the board's finding that there could be no doubt that the Israelis knew exactly what they were doing in attacking the Liberty. I have yet to understand why it was felt necessary to attack this ship or who ordered the attack."[95] In his CIA special collection interview, Helms said, "...I don't think there can be any doubt that the Israelis knew exactly what they were doing. Why they wanted to attack the 'Liberty,' whose bright idea this was, I can't possibly know. But any statement to the effect that they didn't know that it was an American ship and so forth is nonsense."[96][97]

On the morning of the sixth day of the war, President Johnson summoned Helms to the White House Situation Room. Soviet Premier Alexei Kosygin had called to threaten military intervention if the war continued. Defense Secretary Robert S. McNamara suggested that the Sixth Fleet be sent east, from the mid Mediterranean to the Levant. Johnson agreed. Helms remembered the "visceral physical reaction" to the strategic tension, similar to the emotions of the 1962 Cuban Missile Crisis. "It was the world's good fortune that hostilities on the Golan Heights ended before the day was out," wrote Helms later.[98][99]

LBJ: Tuesday lunch

As a result of the CIA's accurate prognosis concerning the duration, logistics, and outcome of the Six-Day War of June 1967, Helms' practical value to the President, Lyndon Baines Johnson, became evident.[100] Recognition of his new status was not long in coming. Helms soon took a place at the table where the president's top advisors discussed foreign policy issues: the regular Tuesday luncheons with LBJ. Helms unabashedly called it "the hottest ticket in town".[101][102][103]

In a 1984 interview with a CIA historian, Helms recalled that following the Six-Day War, he and Johnson had engaged in intense private conversations which addressed foreign policy, including the Soviet Union. Helms went on:

And I think at that time he'd made up his mind that it would be a good idea to tie intelligence into the inner circle of his policy-making and decision-making process. So starting from that time he began to invite me to the Tuesday lunches, and I remained a member of that group until the end of his administration.[105]

Helms' invitation to lunch occurred about three-and-a-half years into Johnson's five-year presidency and a year into Helms' nearly seven-year tenure as DCI. Thereafter in the Johnson administration, Helms functioned in proximity to high-level policymaking, with continual access to America's top political leadership. It constituted the pinnacle of Helms' influence and standing in Washington. Helms describes the "usual Tuesday lunch" in his memoirs.

[W]e gathered for a sherry in the family living room on the second floor of the White House. If the President, who normally kept to a tight schedule, was a few minutes late, he would literally bound into the room, pause long enough to acknowledge our presence, and herd us into the family dining room, overlooking Pennsylvania Avenue. Seating followed protocol, with the secretary of state (Dean Rusk) at the President's right, and the secretary of defense (Robert McNamara, later Clark Clifford) at his left. General Bus Wheeler (the Chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff) sat beside the secretary of defense. I sat beside Dean Rusk. Walt Rostow (the Special Assistant for National Security Affairs), George Christian (the White House Press Secretary), and Tom Johnson (the deputy press secretary) made up the rest of the table.[106]

In CIA interviews long after the war ended, Helms recalled the role played in policy discussions. As the neutral party, Helms could come up with facts applicable to the issue at hand. The benefit of such a role was the decisiveness in "keeping the game honest". Helms comments that many advocates of particular policy positions will almost invariably 'cherry pick' facts supporting their positions, whether consciously or not. Then the voice of a neutral could perform a useful function in helping to steer the conversation on routes within realistic parameters.[107]

The out-sized political personality of Johnson, of course, was the dominating presence at lunch. From his perch Helms marveled at the learned way President Johnson employed the primary contradictions in his personality to direct those around him, and forcefully manage the atmosphere of discourse.[108][109]

Regarding the perennial issues of Vietnam, a country in civil war, Helms led as an important institutional player in the political mix of Washington. Staff within the CIA were divided on the conflict. As the DCI, Helms' daily duties involved the difficult task of updating CIA intelligence and reporting on CIA operations to the American executive leadership. Vietnam then dominated the news. Notoriously, the American political consensus eventually broke. The public became sharply divided, with the issues being vociferously contested. About the so-called Vietnamese 'quagmire' it seemed confusion reigned within and without. Helms saw himself as struggling to best serve his view of America and his forceful superior, the President.[110][111][112]

Viet Cong numbers

Differences and divisions might emerge within the ranks of analysts, across the spectrum of the USG Intelligence Community. Helms had a statutory mandate with the responsibility for reconciling the discrepancies in information, or the conflicting views, promoted by the various American intelligence services, e.g., by the large Defense Intelligence Agency or by the Bureau of Intelligence and Research at the United States State Department. While the CIA might agree on its own Estimates, other department reports might disagree, causing difficulties, and making inter-agency concord problematic. The process of reaching the final consensus could become a contentious negotiation.[113][114][115]

In 1965, Johnson substantially escalated the war by sending large numbers of American combat troops to fight in South Vietnam, and ordered warplanes to bomb the North. Nonetheless, the military put stiff pressure on him to escalate further. In the "paper wars" that followed, Helms at the CIA was regularly asked for intelligence reports on military action, e.g., the political effectiveness of bombing Hanoi. The military resented such a review of its conduct in the war.[116]

The American strategy had become the pursuit of a war of attrition. The objective was to make the Viet Cong enemy suffer more losses than it could timely replace. Accordingly, the number of combatants fielded by the communist insurgency at any one time was a key factor in determining whether the course of the war was favorable or not. The political pressure on the CIA to conform to the military's figures of enemy casualties became intense. Under Helms, CIA reports on the Viet Cong order of battle numbers were usually moderate; the CIA also questioned whether the strategy employed by the U.S. Army would ever compel Hanoi to negotiate. Helms himself was evidently sceptical, yet Johnson never asked for his personal opinion.[117] This dispute between the Army and the CIA over the number of Viet Cong combatants became bitter, and eventually common knowledge in the administration.[118][119]

According to one source, CIA Director Richard Helms "used his influence with Lyndon Johnson to warn about the growing dangers of U.S. involvement in Vietnam."[120] On the other hand, Stansfield Turner (DCI 1977–1981) describes Helms' advisory relationship to Lyndon Johnson as being overly loyal to the office of president. Hence, the CIA staff's frank opinions on Vietnam were sometimes modified before reaching President Johnson.[121] At one point the CIA analysts estimated enemy strength at 500,000, while the military insisted it was only 270,000. No amount of discussion could resolve the difference. Eventually, in September 1967, the CIA under Helms went along with the military's lower number for the combat strength of the Vietnamese Communist forces.[122][123] This led a CIA analyst directly involved in this work to file a formal complaint against DCI Helms, which was accorded due process within the Agency.[124][125]

Vietnam: Phoenix

As a major element in his counterinsurgency policy, Ngo Dinh Diem (President 1954–1963) had earlier introduced the establishment of strategic hamlets in order to contest Viet Cong operations in the countryside.[126][127] From several antecedents the controversial Phoenix program was launched during 1967–1968.[128] Various Vietnamese forces (intelligence, military, police, and civilian) were deployed in the field against Viet Cong support networks. The CIA played a key role in its design and leadership,[129][130] and built on practices developed by Vietnamese, i.e., the provincial chief, Colonel Tran Ngoc Chau.[131][132]

CIA was not officially in control of Phoenix, CORDS was. In early 1968, DCI Helms had agreed to allow William Colby to take a temporary leave of absence from the CIA in order to go to Vietnam and lead CORDS, a position with ambassadorial rank. In doing so, Helms personally felt "thoroughly disgusted"... thinking Robert Komer had "put a fast one over on him". Komer was then in charge of the CORDS pacification program in South Vietnam. Recently Helms had promoted Colby to a top CIA post: head of the Soviet Division (before Colby had been running the CIA's Far East Division, which included Vietnam). Now Colby transferred out of CIA, to CORDS to run Phoenix.[133][134] Many other Americans worked to monitor and manage the Phoenix program including, according to Helms, "a seemingly ever-increasing number of CIA personnel".[135][136][137]

After receiving special Phoenix training, Vietnamese forces in rural areas went head to head against the Viet Cong Infrastructure, e.g., they sought to penetrate communist organizations, to arrest and interrogate or slay their cadres.[138][139] The Vietnam War resembled a ferocious civil war; the Viet Cong had already assassinated thousands of Vietnamese village leaders.[140][141] Unfortunately, in its strategy of fighting fire with fire, forces in the Phoenix program used torture, and became entangled in actions involving local and official corruption, resulting in many questionable killings, perhaps thousands.[142][143][144] Despite its grave faults, Colby opined that the program did work well enough to stop Viet Cong gains. Colby favorably compared Operation Phoenix with the CIA's relative success in its "secret war" in Laos.[145][146]

Helms notes that the early efforts of Phoenix "were successful, and of serious concern to the NVN [North Vietnamese] leadership". Helms then goes on to recount the Phoenix program's progressive slide into corruption and counterproductive violence, which came to nullify its early success. Accordingly, by the time it was discontinued Phoenix had become useless in the field and a controversial if not a notorious political liability.[147][148][149] Helms in his memoirs presents this situation:

PHOENIX was directed and staffed by Vietnamese over whom the American advisors and liaison officers did not have command or direct supervision. The American staff did its best to eliminate the abuse of authority—the settling of personal scores, rewarding of friends, summary executions, prisoner mistreatment, false denunciation, illegal property seizure—that became the by-products of the PHOENIX counterinsurgency effort. In the blood-soaked atmosphere created by Viet Cong terrorism, the notion that regulations and directives imposed by foreign liaison officers could be expected to curb revenge and profit-making was unrealistic.[150]

After the war, interviews were conducted with Vietnamese communist leaders and military commanders familiar with the Viet Cong organization, its war-making capacity, and support infrastructure. They said the Phoenix operations were very effective against them, reports Stanley Karnow.[151] Thomas Ricks, in evaluating the effectiveness of the counterinsurgency tactics of the Marine Corps and of the Phoenix program, confirmed their value by reference to "Hanoi's official history of the war".[152][153] If one discounts the corrupt criminality and its political fallout, the Phoenix partisans were perhaps better able tactically to confront the elusive Viet Cong support networks, i.e., the sea in which the fish swam, than the regular units of the ARVN and the U. S. Army.[154][155] Yet the military lessons of the war in full complexity were being understood by the Army, later insisted Colonel Summers.[156]

Regarding the Phoenix legacy, a sinister controversy haunts it.[157][158] Distancing himself, Helms summarized: "As successful a program as PHOENIX was when guided by energetic local leaders," as a national program it succumbed to political corruption and "failed".[159] Colby admitted serious faults, yet in conclusion found a positive preponderance.[160] "It was not the CIA," writes John Ranelagh, "that was responsible for the excesses of Phoenix (although the agency clearly condoned what was happening)."[161] Author Tim Weiner compares the violent excesses of Phoenix to such associated with the early years of the Second Iraq War.[162][163][164]

Johnson withdraws

In America, what became the Vietnam War lost domestic political support, and seriously injured the popularity of the Johnson administration. In the spring of election year 1968, following the unexpected January Tet offensive in Vietnam, the war issue reached a crisis.[165][166] In March, Helms prepared yet another special CIA report for the President and arranged for CIA officer George Carver to present it in person to Johnson. Carver was then the CIA's Special Assistant for Vietnam Affairs (SAVA).[167]

Helms writes, "In his typically unvarnished manner, George had presented a bleak but accurate view of the situation and again demonstrated that the NVN strength in South Vietnam was far stronger than had been previously reported by MACV." Carver "closed by saying in effect that not even the President could not tell the American voters on one day that the United States planned to get out of Vietnam, and on the next day tell Ho Chi Minh that we will stick it out for twenty years. With this LBJ rose like a roasted pheasant and bolted from the room." But Johnson soon returned.[168][169][170] Helms described what happened next.

The President, who was a foot and a half taller and a hundred pounds heavier than George, struck him a resounding clap on the back and caught his hand in an immense fist. Wrenching George's arm up and down with a pumping motion that might have drawn oil from a dry Texas well, Johnson congratulated him on the briefing, and on his services to the country and its voters. As he released George, he said, 'Anytime you want to talk to me, just pick up the phone and come over.' It was a vintage LBJ performance.[171]

Earlier, a group of foreign policy elders, known as The Wise Men, having first heard from the CIA, then confronted Johnson about the difficulty of winning in Vietnam. The president was unprepared to accept their negative findings. "Lyndon Johnson must have considered March 1968 the most difficult month of his political career," wrote Helms later. Eventually, this frank advice contributed to Johnson's decision in March to withdraw from the 1968 presidential election.[172][173][174]

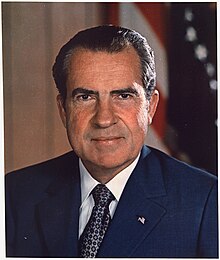

Nixon presidency

In the 1968 Presidential election, the Republican nominee Richard M. Nixon triumphed over the Democrat, Vice President Hubert Humphrey. Shortly after the election, President Johnson invited President-Elect Nixon to his LBJ Ranch in Texas for a discussion of current events. There Johnson introduced Nixon to a few members of his inner circle: Dean Rusk at State, Clark Clifford at Defense, Gen. Earle Wheeler, and DCI Richard Helms. Later Johnson in private told Helms that he had represented him to Nixon as a political neutral, "a merit appointment", a career federal official who was good at his job.[175][176]

Nixon then invited Helms to his pre-inauguration headquarters in New York City, where Nixon told Helms that he and J. Edgar Hoover at FBI would be retained as "appointments out of the political arena". Helms expressed his assent that the DCI was a non-partisan position. Evidently, already Nixon had made his plans when chief executive to sharply downgrade the importance of the CIA in his administration, in which case Nixon himself would interact very little with his DCI, e.g., at security meetings.[177][178]

Role of agency

The ease of access to the president that Helms enjoyed in the Johnson Administration changed dramatically with the arrival of President Richard Nixon and Nixon's national security advisor Henry Kissinger. In order to dominate policy, "Nixon insisted on isolating himself" from the Washington bureaucracy he did not trust. His primary gatekeepers were H.R. Haldeman and John Ehrlichman; they screened Nixon from "the face-to-face confrontations he so disliked and dreaded." While thus pushing away even top officials, Nixon started to build policy-making functions inside the White House. From a secure distance he would direct the government and deal with "the outside world, including cabinet members".[179][180] Regarding intelligence matters, Nixon appointed Kissinger and his team to convey his instructions to the CIA and sister services. Accordingly, Nixon and Kissinger understood that "they alone would conceive, command, and control clandestine operations. Covert action and espionage could be tools fitted for their personal use. Nixon used them to build a political fortress at the White House."[181]

In his memoirs, Helms writes of his early meeting with Kissinger. "Henry spoke first, advising me of Nixon's edict that effective immediately all intelligence briefings, oral or otherwise, were to come through Kissinger. All intelligence reports? I asked. Yes."[182] A Senate historian of the CIA observes that "it was Kissinger rather than the DCIs who served as Nixon's senior intelligence advisor. Under Kissinger's direction the NSC became an intelligence and policy staff."[183][184] Under Nixon's initial plan, Helms was to be excluded even from the policy discussions at the National Security Council (NSC) meetings.[185][186][187]

Very early in the Nixon administration it became clear that the President wanted Henry Kissinger to run intelligence for him and that the National Security Council staff in the White House, under Kissinger, would control the intelligence community. This was the beginning of a shift of power away from the CIA to a new center: the National Security Council staff.[188]

Stansfield Turner (DCI 1977–1981) describes Nixon as basically being hostile to the CIA, questioning its utility and practical value, based on his low evaluation of the quality of its information. Turner, who served under President Carter, opines that Nixon considered the CIA to be full of elite "liberals" and hence contrary to his policy direction.[189][190] Helms agreed regarding Nixon's hostility toward the CIA, also saying in a 1988 interview that "Nixon never trusted anybody."[191][192] Yet Helms later wrote:

Whatever Nixon's views of the Agency, it was my opinion that he was the best prepared to be President of any of those under whom I served—Eisenhower, Kennedy, and Johnson. ... Nixon had the best grasp of foreign affairs and domestic politics. His years as Vice President had served him well.[193]

When Nixon attended NSC meetings, he would often direct his personal animosity and ire directly at Helms, who led an agency Nixon considered overrated, whose proffered intelligence Nixon thought of little use or value, and which had a history of aiding his political enemies, according to Nixon. Helms found it difficult to establish a cordial working relationship with the new president.[194][195][196][197] Ray Cline, former Deputy Director of Intelligence at CIA, wrote how he saw the agency under Helms during the Nixon years:

Nixon and his principal assistant, Dr. Kissinger, disregarded analytical intelligence except for what was convenient for use by Kissinger's own small personal staff in support of Nixon-Kissinger policies. Incoming intelligence was closely monitored and its distribution controlled by Kissinger's staff to keep it from embarrassing the White House... . " They employed "Helms and the CIA primarily as an instrument for the execution of White House wishes" and did not seem "to understand or care about the carefully structured functions of central intelligence as a whole. ... I doubt that anyone could have done better than Helms in these circumstances.[198]

Under the changed policies of the Nixon administration, Henry Kissinger in effect displaced the DCI and became "the President's chief intelligence officer".[199] Kissinger writes that, in addition, Nixon "felt ill at ease with Helms personally."[200]

Domestic Chaos

Under both the Johnson and Nixon administrations, the CIA was tasked with domestic surveillance of protest movements, particularly anti-war activities, which efforts later became called Operation CHAOS.[201] Investigations were opened on various Americans and their organizations based on the theory that they were funded and/or influenced by foreign actors, especially the Soviet Union and other communist states. The CIA clandestinely gathered information on Ramparts magazine, many anti-war groups, and others, eventually building thousands of clandestine files on American citizens.[202][203] These CIA activities, if not outright illegal (the declared opinion of critics),[204][205] were at the margin of legality as the CIA was ostensibly forbidden from domestic spying.[206] Later in 1974, the Chaos operation became national news, which created a storm of media attention.[207]

With the sudden rise in the United States during the mid-1960s of the opposition to the Vietnam War, President Johnson had become suspicious, surmising that foreign communists must be supplying various protest groups with both money and organization skills. Johnson figured an investigation would bring this to light, a project in which the CIA would partner with the FBI. When in 1967 he instructed Helms to investigate, Helms remarked that such activity would involve some risk, as his agency generally was not permitted to conduct such surveillance activity within the national borders.[208] In reply to Helms Johnson said, "I'm quite aware of that." The President then explained that the main focus was to remain foreign. Helms understood the reasons for the president's orders, and the assumed foreign connection.[209][210] Later apparently, both the Rockefeller Commission and the Church Committee found the initial investigation to be within the CIA's legislative charter, although at the margin.[211][212]

As a prerequisite to conducting foreign espionage, the CIA was first to secretly develop leads and contacts within the domestic anti-war movement. In the process its infiltrating agents would acquire anti-war bona fides that would provide them with some amount of cover when overseas. On that rationale, the CIA commenced activity, which continued for almost seven years. Helms kept the operation hidden, from nearly all agency personnel, in Angleton's counterintelligence office.[213][214][215]

Eleven CIA officers grew long hair, learned the jargon of the New Left, and went off to infiltrate peace groups in the United States and Europe. The agency compiled a computer index of 300,000 names of American people and organizations, and extensive files on 7,200 citizens. It began working secretly with police departments all over America. Unable to draw a clear distinction between the far left and the mainstream opposition to the war, it spied on every major organization in the peace movement. At the president's command, transmitted through Helms and the secretary of defense, the National Security Agency turned its immense eavesdropping powers on American citizens.[202][216]

The CIA found no substantial foreign sources of money or influence. When Helms reported these findings to the President, the reaction was hostile. "LBJ simply could not believe that American youth would on their own be moved to riot in protest against U. S. foreign policy," Helms later wrote.[217] Accordingly, Johnson instructed Helms to continue the search with increased diligence. The Nixon presidency later would act to extend the reach and scope of Chaos and like domestic surveillance activity.[218] In 1969 intra-agency opposition to Chaos arose. Helms worked to finesse his critics. Lawrence Houston, the CIA general counsel, became involved, and Helms wrote an office memorandum to justify the Chaos operation to CIA officers and agents.[219][218]

Meanwhile, the FBI was reporting a steady stream of data on domestic anti-war and other 'subversive' activity, but the FBI obstinately refused to provide any context or analysis. For the CIA to do such FBI work was considered a clear violation of its charter.[220] Nixon, however, "remained convinced that the domestic dissidence was initiated and nurtured from abroad."[217] A young lawyer, Tom Charles Huston, was then selected by Nixon in 1970 to manage a marked increase in the surveillance of domestic dissenters and protesters: a multi-agency investigative effort, more thorough and wider in scope. Called the Interagency Committee on Intelligence (ICI), included were the FBI, the Defense Intelligence Agency, the National Security Agency, and the CIA. It would be "a wholesale assault on the peace and radical movements," according to intelligence writer Thomas Powers.[221] The new scheme was delayed, and then the Watergate scandal 'intervened'. In late 1974, the news media discovered a terminated Operation Chaos.[222][223]

Soviet missiles

The Soviet Union developed a new series of long-range missiles, called the SS-9 (NATO codename Scarp). A question developed concerning the extent of their capability to carry nuclear weapons; at issue was whether the missile was a Multiple independently targetable reentry vehicle (MIRV) or not. The CIA information was that these missiles were not 'MIRVed' but Defense intelligence considered that they were of the more potent kind. If so, the Soviet Union was possibly aiming at a first strike nuclear capacity. The Nixon administration, desiring to employ the existence of such a Soviet threat to justify a new American antiballistic missile system, publicly endorsed the Defense point of view. Henry Kissinger, Nixon's national security advisor, asked Helms to review the CIA's finding, yet Helms initially stood by his analysts at the CIA. Eventually, however, Helms compromised.[224][225]

Melvin Laird, Nixon's Secretary of Defense, had told Helms that the CIA was intruding outside its area, with the result that it 'subverted administration policy'. Helms, in part, saw this MIRV conflict as part of bureaucratic maneuvering over extremely difficult-to-determine issues, in which the CIA had to find its strategic location within the new Nixon administration. Helms later remembered:

I realized that there was no convincing evidence in the Agency or at the Pentagon which would prove either position. Both positions were estimates—speculation—based on identical fragments of data. My decision to remove the contested paragraph was based on the fact that the Agency's estimate—that the USSR was not attempting to create a first-strike capability – as originally stated in the earlier detailed National Estimate would remain the Agency position.[226]

One CIA analyst, Abbott Smith, viewed this flip-flop not only as "a cave-in on a matter of high principle", according to author John Ranelagh, "but also as a public slap in the face from his director, a vote of no confidence in his work." Another analyst at the United States Department of State, however, had reinserted the "contested paragraph" into the intelligence report. When a few years later the nature of the Soviet SS-9 missiles became better understood, the analysts at the CIA and at State were vindicated. "The consensus among agency analysts was that Dick Helms had not covered himself with glory this time."[227]

Vietnamization

Nixon pursued what he called "peace with honor", yet critics called its aim a "decent interval".[228] The policy was called Vietnamization.[229][230] To end the war favorably he focused on the peace negotiations in Paris. There Henry Kissinger played the major role in bargaining with the North Vietnamese. Achieving peace proved difficult; in the meantime, casualties mounted. Although withdrawing great numbers of American troops, Nixon simultaneously escalated the air war. He increased the heavy bombing of Vietnam, also of Laos and Cambodia, and widened the scope of the conflict by invading Cambodia. While these actions sought to gain bargaining power at the Paris conference table, they also drew a "firestorm" of college protests in America.[231][232] Kissinger describes a debate over the mining of Haiphong harbor, in which he criticizes Helms at CIA for his disapproval of the plan. In Kissinger's telling, here Helms' opposition reflected the bias of CIA analysts, "the most liberal school of thought in the government."[233]

When contemplating his administration's inheritance of the Vietnam War, Nixon understood the struggle in the context of the cold war. He viewed Vietnam as critically important. Helms recalled him as saying, "There's only one number one problem hereabouts and that's Vietnam—get on with it."[234] Nixon saw that the ongoing Sino-Soviet split presented America with an opportunity to triangulate Soviet Russia by opening relations with the People's Republic of China. It might also drive a wedge between the two major supporters of North Vietnam.[235] While here appreciating the CIA reports Helms supplied him on China, Nixon nonetheless kept his diplomatic travel preparations within the White House and under wraps.[236] To prepare for Nixon's 1972 trip to China, Kissinger ordered that CIA covert operations there, including Tibet,[237] come to a halt.[238]

In the meantime, Vietnamization signified the withdrawal of American troops from Vietnam, while the brunt of the fighting was shifted to South Vietnamese armed forces. This affected all CIA operations across the political-military landscape. Accordingly, DCI Helms wound down many CIA activities, e.g., civic projects and paramilitary operations in Vietnam, and the "secret war" in Laos. The Phoenix program once under Colby (1967–1971) was also turned over to Vietnamese direction and control.[239][240] The 1973 Paris Peace Accords, however, came after Helms had left the CIA.

To sustain the existence of the South Vietnam regime, Nixon massively increased American military aid. In 1975, the regime's army quickly collapsed when regular army units of the Communist forces attacked.[241] "Moral disintegration alone can explain why an army three times the size and possessing more than five times the equipment of the enemy could be as rapidly defeated as the ARVN was between March 10 and April 30, 1975," commented Joseph Buttinger.[242] American military deaths from the war were over 47,000, with 153,000 wounded. South Vietnamese military losses (using low figures) were about 110,000 killed and 500,000 wounded. Communist Vietnamese military losses were later announced: 1,100,000 killed and 600,000 wounded. Hanoi also estimated that total civilian deaths from the war, 1954 to 1975, were 2,000,000. According to Spencer C. Tucker, "The number of civilians killed in the war will never be known with any accuracy; estimates vary widely, but the lowest figure given is 415,000."[243]

Chile: Allende

Helms engaged in efforts to block the socialist programs of Salvador Allende of Chile, actions done at President Nixon's behest. The operation was code-named Project Fubelt. After Allende's victory in the 1970 election, CIA jumped into action with a series of sharp and divisive maneuvers. Nonetheless, Allende was inaugurated as president of Chile. Thereafter, the CIA's efforts declined in intensity, though softer tactics continued. Three years later (11 Sept. 1973) the military coup led by Augusto Pinochet violently ended the democratically elected regime of President Allende.[246][247][248]

During the 1970 Chilean presidential election, the USG had sent financial and other assistance to the two candidates opposing Allende, who won anyway.[249][250][251] Helms states that then, on Sept. 15, 1970, he met with President Nixon who ordered the CIA to support an army coup to prevent an already elected Allende from being confirmed as president; it was to be kept secret. "He wanted something done and he didn't care how," Helms later characterized the order.[252][253] The secret, illegal (in Chile) activity ordered by Nixon was termed "track II" to distinguish it from the CIA's covert funding of Chilean "democrats" here called "track I".[254][255][256] Accordingly, the CIA took assorted covert steps, including actions to badger a law-abiding Chilean army to seize power. CIA agents were once in communication, but soon broke off such contact, with rogue elements of the country's military who later assassinated the "constitutionally minded" General René Schneider, the Army Commander-in-Chief. Following this criminal violence, the Chilean army's support swung firmly behind Allende, whom the Congress confirmed as president of Chile on November 3, 1970.[257][258] CIA did not intend the killing. "At all times, however, Helms made it plain that assassination was not an option."[259][260] Nixon and Kissinger blamed Helms for Allende's presidency.[257][261]

Thereafter, the CIA funneled millions of dollars to opposition groups, e.g., political parties, the media, and striking truck drivers, in a continuing, long-term effort to destabilize Chile's economy and so subvert the Allende administration. Nixon's initial, memorable phrase for such actions had been "to make the Chilean economy scream".[262] Even so, according to DCI Helms, "In my remaining months in office, Allende continued his determined march to the left, but there was no further effort to instigate a coup in Chile." Helms here appears to parse between providing funds for Allende's political opposition ("track I") versus actually supporting a military overthrow ("track II").[263] Although in policy disagreement with Nixon, Helms assumed the role of the "good soldier" in following his presidential instructions.[264] Helms left office at the CIA on February 2, 1973, seven months before the coup d'etat in Chile.[265]

Another account of CIA activity in Chile, however, states that during this period 1970–1973 the CIA worked diligently to propagandize the military into countenancing a coup, e.g., the CIA supported and cultivated rightists in the formerly "constitutionally minded" army to start thinking 'outside the box', i.e., to consider a coup d'etat. Thus, writes author Tim Weiner, while not per se orchestrating the 1973 coup, the CIA worked for years, employing economic and other means, to seduce the army into doing so.[266] Allende's own actions may have caused relations with his army to become uneasy.[267] The CIA sowed "political and economic chaos in Chile" which set the stage for a successful coup, Weiner concludes.[268][269][270] Hence, Helms's careful parsing appears off the mark. Views and opinions differ, e.g., Kissinger contests,[271] what William Colby in part acknowledges.[272]

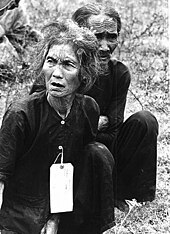

After Helms' departure from the CIA in early 1973, Nixon continued to work directly against the Allende regime.[273] Although elected with 36.3% of the vote (to 34.9% for runner-up in a three-way contest), Allende as President reportedly ignored the Constitución de 1925 in pursuit of his socialist policies, namely, ineffective projects which proved very unpopular and polarizing.[274] The military junta's successful September 1973 coup d'etat was unconstitutional. Thousands of citizens were eventually killed and tens of thousands were held as political prisoners, many being tortured.[275][276][277][278][279] The civil violence of the military coup provoked widespread international censure.[280][281]

Watergate

| Watergate scandal |

|---|

|

| Events |

| People |

After first learning of the Watergate scandal on June 17, 1972, Helms developed a general strategy to distance the CIA from it altogether, including any third-party investigations of Nixon's role in the precipitating break-in.[283][284] The scandal created a flurry of media interest during the 1972 Presidential election, but only reached its full intensity in the following years. Among those initially arrested (the "plumbers") were former CIA employees; there were loose ends with the agency.[285] Helms and DDCI Vernon Walters became convinced that CIA top officials had no culpable role in the break-in. It soon became apparent, however, that it was "impossible to prove anything to an inflamed national press corps already in full cry" while "daily leaks to the press kept pointing at CIA". Only later did Helms conclude that "the leaks were coming directly from the White House" and that "President Nixon was personally manipulating the administration's efforts to contain the scandal".[286][287][288]

On June 23, 1972, Nixon and Haldeman discussed the progress the FBI was making in their investigation and an inability to control it.[289] In discussing how to ask Helms for his assistance to seek a "hold" on the FBI investigation, Nixon said "well, we protected Helms from one hell of a lot of things".[289] Nixon's team (chiefly Haldeman, Ehrlichman, and Dean) then asked Helms in effect to assert a phony national security reason for the break-in and, under that rationale, to interfere with the ongoing FBI investigation of the Watergate burglaries. Such a course would also involve the CIA in posting bail for the arrested suspects. Initially Helms made some superficial accommodation that stalled for several weeks the FBI's progress. At several meetings attended by Helms and Walters, Nixon's team referred to the Cuban Bay of Pigs fiasco, using it as if a talisman of dark secrets, as an implied threat against the integrity of CIA. Immediately, sharply, Helms turned aside this gambit.[290][291][292][293]

By claiming then a secrecy privilege for national security, Helms could have stopped the FBI investigation, but he decisively refused the President's repeated request for cover. Stansfield Turner (DCI under Carter) called this "perhaps the best and most courageous decision of his career". Nixon's fundamental displeasure with Helms and the CIA increased. Yet "CIA professionals remember" that Helms "stood up to the president when asked to employ the CIA in a cover-up."[294][295][296][297][298]

John Dean, Nixon's White House Counsel, reportedly asked for $1 million to buy the silence of the jailed Watergate burglars. Helms in a 1988 interview stated:

"We could get the money. ... We didn't need to launder money—ever." But "the end result would have been the end of the agency. Not only would I have gone to jail if I had gone along with what the White House wanted us to do, but the agency's credibility would have been ruined forever."[299]

For the time being, however, Helms had succeeded in distancing the CIA as far as possible from the scandal.[300] Yet the Watergate scandal became a major factor (among others: the Vietnam war) in the great shift of American public opinion about the federal government: their suspicions aroused, many voters turned critical. Hence, the political role of the Central Intelligence Agency also became a subject of controversy.[301][302][303]

Helms dismissed

Immediately after Nixon's re-election in 1972, he called for all appointed officials in his administration to resign; Nixon here sought to gain more personal control over the federal government. Helms did not consider his position at CIA to be a political job, which was the traditional view within the Agency, and so did not resign as DCI. Previously, on election day Helms had lunch with General Alexander Haig, a top Nixon security advisor; Haig didn't know Nixon's mind on the future at CIA. Evidently neither did Henry Kissinger, Helms discovered later. On November 20, Helms came to Camp David to an interview with Nixon about what he thought was a "budgetary matter". Nixon's chief of staff H.R. Haldeman also attended. Helms was informed by Nixon that his services in the new administration would not be required.[304] On Helms' dismissal William Colby (DCI Sept. 1973 to Jan. 1976) later commented that "Dick Helms paid the price for that 'No' [to the White House over Watergate]."[305][306]

In the course of this discussion, Nixon learned or was reminded that Helms was a career civil servant, not a political appointee. Apparently spontaneously, Nixon then offered him the ambassadorship to the Soviet Union. After shortly considering it, Helms declined, wary of the potential consequences of the offer, considering his career in intelligence. "I'm not sure how the Russians might interpret my being sent across the lines as an ambassador," Helms remembers telling Nixon. Instead Helms proposed being sent to Iran.[307][308] Nixon assented. Among other things Nixon perhaps figured Helms, after managing CIA's long involvement in Iranian affairs, would be capable in addressing issues arising out of Nixon's recent policy decision conferring on the shah his new role as "policeman of the Gulf".[309][310]

Helms also suggested that since he could retire when he turned 60, he might voluntarily do so at the end of March. So it was agreed, apparently. But instead the event came without warning as Helms was abruptly dismissed when James R. Schlesinger was named the new DCI on February 2, 1973.[311]

The timing caught me by surprise. I had barely enough time to get my things out of the office and to assemble as many colleagues of all ranks as possible for a farewell. ...

A few days later, I encountered Haldeman. "What happened to our understanding that my exit would be postponed for a few weeks?" I asked. "Oh, I guess we forgot," he said with the faint trace of a smile.

And so it was over."[312]

Ambassador to Iran

After Helms left the leadership of the CIA, he began his service as U.S. ambassador to Iran as designated by President Nixon.[313][314] This had caused the dismissal of the then current ambassador, Joseph Farland.[315] After being confirmed by the Senate, in April 1973 Helms proceeded to his new residence in Tehran, where he served as the American representative until resigning effective January 1977. During these years, however, his presence was often required in Washington, where he testified before Congress in hearings about past CIA activities, including Watergate. His frequent flights to the United States lessened somewhat his capacity to attend to being ambassador.[316][317]

At the Shah's court

"The presentation of ambassadorial credentials to the Shah was a rather formal undertaking," reads a photograph caption in Helms' memoirs, which shows him in formal attire, standing before the Shah who is dressed in military uniform.[318] Helms enjoyed an elite student experience which he shared with the Shah, as circa 1930, both had attended Le Rosey, a French-language prep school in Switzerland.[319]

Decades later, the CIA station chief in Iran first introduced Helms to the Shah. Helms was there about an installation to spy on the Soviets:[320] "I had first met the Shah in 1957 when I visited Tehran to negotiate permission to place some sophisticated intercept equipment in northern Iran."[321]

A "celebrated" story was told in elite circles about Helms' appointment. The Soviet ambassador had said with a sneer, to Amir Abbas Hoveyda the Shah's prime minister, "We hear the Americans are sending their Number One spy to Iran." Hoveyda replied, "The Americans are our friends. At least they don't send us their Number Ten spy."[322] Helms, for his part, referred to Hoveyda as "Iran's most consummate politician."[323]

For many years, the CIA had operated extensive technical installations to monitor Soviet air traffic across Iran's northern border.[324] Also the CIA, along with Mossad and USAID, since the early 1950s had trained and supported the controversial Iranian intelligence and police agency SAVAK.[325] Further from 1972 to 1975 the CIA was involved in assisting Iran with its project to support the Kurdish struggle against Iraq. As a result of this security background and official familiarity with the government of Iran, Helms figured that as the American ambassador he could "hit the ground running" when he started work in Tehran.[326][327]

Long before Helms arrived in country his embassy, and other western embassies as well, entertained an "almost uncritical approval of the Shah. He was a strong leader, a reformer who appreciated the needs of his people and who had a vision of a developed, pro-Western, anti-Communist, prosperous Iran." The shah remained an ally. "Too much had been invested in the Shah—by European nations as well as by the U.S.—for any real changes in policy."[328][329] Helms inspected and adjusted the security provided for the embassy, which was located in the city on 25-acres with high walls. A CIA officer accompanied Helms wherever he went. The usual ambassador's car was "a shabby beige Chevrolet" with armor-plating. There was "the traditional ambassador's big black Cadillac, with the flag flying from the front fender" but Helms used it only once, accompanied by his wife.[330][331]

The ruler and Iran

Most important for his effectiveness would be to establish a good working relationship with the ruler. All the while, the shah's terminal illness of prostate cancer remained a well-kept secret from everyone.[332][333] Helms found himself satisfied with his "as much as might be asked for" dealings with the Shah. The monarch was notorious for an "I speak, you listen" approach to dialogue.[334] Yet Helms describes lively conversations with "polite give-and-take" in which the shah never forgot his majesty; these discussions could end with an agreement to disagree. The shah allowed that they by happenstance might meet at a social function and then "talk shop". Usually they met in private offices, the two alone, where it was "tête à tête with no note-takers or advisors."[335][336]

British author and journalist William Shawcross several times makes the point that the shah prohibited foreign governments from any contact with his domestic political opposition. Replying to one such request for access, by the Secretary-General of the United Nations, an 'irritated' shah replied "I will not have any guest of mine waste a moment on these ridiculous people." As with other ambassadors before and during his tenure, Helms was reluctant to cross the shah on this point because of the fear of "being PNG'ed (made persona non grata)." For any ambassador to do so "would at the very least have jeopardized his country's export opportunities in Iran." Consequently, "American and other diplomats swam in a shallow pool of courtiers, industrialists, lawyers, and others who were somehow benefiting from the material success of the regime. ¶ ... people more or less licensed by the Shah." About the immediate court, however, a U.N. official wrote, "There was an atmosphere of overwhelming nouveau-riche, meretricious chi-chi and sycophancy ..."[337][338] Helms himself managed to circulate widely among the traditional elites, e.g., becoming a "close friend" of the aristocrat Ahmad Goreishi.[339]

The shah's policy of keeping foreign agents and officials away from his domestic foes applied equally to the CIA. In fact, the Agency remained somewhat uninformed about his foes, but for what information SAVAK (Iran's state security) gave it.[citation needed] The CIA evidently did not even closely monitor the shah's activities. During Helms' last year this situation was being reviewed, but the State Department seemed complacent and willing to rely on the shah's soliloquies and its own diplomatic queries.[340][341] While Helms' 'notorious' connection to the CIA might have been considered an asset by the shah and his circle, many Iranians viewed the American embassy and its spy Agency as distressing reminders of active foreign meddling in their country's affairs, and of the CIA's 1953 coup against the civil democrat Mohammad Mossadegh.[342][343][344][345] "[F]ew politically minded Iranians doubted that the American embassy was deeply involved in Iranian domestic politics and in promoting particular individuals or agendas" including actions by "the CIA station chief in Tehran".[346]

Events and views

During his first year as ambassador, Helms had fielded the American and Iranian reaction to the 1973 Arab oil embargo and consequent price hikes following the Yom Kippur War. Immediately, Helms made requests to the shah regarding fueling favors for the United States Navy near Bandar Abbas. Subsequently, the Shah, flush with increased oil revenue, had placed huge orders for foreign imports and American military hardware, e.g., high performance warplanes. Helms wrote in his memoirs, "Foreign businessmen flooded Tehran. Few had any knowledge of the country; fewer could speak a word of Persian." Tens of thousands of foreign commercial agents, technicians and experts, took up temporary residence. "There is no doubt [the Shah] tried to go too fast. Which led to the ports' congestion and the overheating of the economy," Helms later commented.[347][348][349][350] The 'oil bonanza' followed by the rapid expenditure of 'petrodollars' led to an accelerated corruption involving enormous sums.[351][352]

In March 1975, Helms learned the shah alone had negotiated a major agreement with Saddam Hussein of Iraq while in Algiers at an OPEC meeting. There the Algerian head of state Houari Boumedienne had translated the shah's French into Arabic for the negotiation. As part of the deal, the shah had disowned, quit his support for the Kurdish struggle in Iraq. The resulting treaty was evidently a surprise to the shah's own ministers, as well as to Helms and the USG.[353][354] As a result, the CIA also abandoned the Kurds, whose struggling people became another of those stateless nations who would remember with "regret and bitterness" their dealings with the Agency.[355]

Helms articulated several understandings, derived from his working knowledge and experiences as ambassador in Iran. "He came to realize that he could never understand the Iranians," writes William Shawcross. He quotes Helms, "They have a very different turn of mind. Here would be ladies, dressed in Parisian clothes. ... But before they went on trips abroad, they would ship up to Mashhad in chadors to ask for protection." Helms with his wife had visited the pilgrimage site in Mashhad, 'the tomb of the eighth Imam'. As to the shah's statecraft, Helms' May 1976 memo observes, "Iranian government and society are highly structured and authoritarian and all major decisions are made at the top. Often even relatively senior officials are not well informed about policies and plans and have little influence on them."[356] In July 1976 Helms send a message to the U.S. Department of State which, while confident, again voiced various concerns, e.g., about the "inadequate 'political institutionalization'" of the regime.[357] Professor Abbas Milani comments that in 1975 Helms had "captured the nature of the shah's vulnerability when he wrote that 'the conflict between rapid economic growth and modernization vis-à-vis a still autocratic rule' was the greatest uncertainty about the shah's future." Milani, looking ahead after Helms' departure, writes that the election of President Carter in 1976 "forced the Shah to expedite his liberalization plans."[358][359]

During the course of his service as ambassador, Helms had dealt with the 1973 oil crisis and Iran's oil bonanza, and the shah's 1975 deal with Iraq and abandonment of the Kurds. In 1976, Secretary of State Kissinger visited Iran. He agreed to Helms' plan to resign as ambassador before the Presidential election.[360] Helms submitted his resignation to President Ford in the middle of October. Meanwhile, the grand jury sitting in Washington had "shifted the focus of its investigation" about past activities of the CIA.[361]

Secrets: policy, politics

During the mid-1970s in the United States, an emerging public attitude against CIA malfeasance had become mainstream. Consequently, politicians no longer deigned to countenance a blanket exception to "what-might-be-questionable" CIA activities. With regard to the application of the Constitution, henceforth all USG agencies were expected to conform explicitly to usual principles of transparency. Earlier, Helms had given testimony about prior covert CIA actions in Chile, at a time when he considered that older, pre-existing, informal understandings concerning the CIA still prevailed in Congress. This testimony was later judged under the new rules, which led to his perjury indictment in a court of law. His advocates thus claimed that Helms was unfairly held to a form of double standard.[362][363]

Year of intelligence

During the 1960s and 1970s, there was a dramatic, fundamental shift in American society generally, which profoundly affected public political behavior. Elected officials were compelled to confront new constituents with new attitudes. In particular, for the Central Intelligence Agency, the societal change altered notions of what was considered 'politically acceptable conduct'.[364] In the early cold war period, the Agency had been somewhat exempt from normal standards of accountability, so that it could employ its special espionage and covert capacities against what was understood as an amoral communist enemy. At times during this period, the CIA operated under a cloak of secrecy, where it met the ideological foe in a gray-and-black world. In that era, normal Congressional oversight was informally modified to block unwanted public scrutiny, which might be useful to the enemy.[365][366]

An immediate cause of the surge in Congressional oversight activity may be sourced in the American people's loss of confidence in the USG due to the Watergate scandal. Also, the apparent distortions and dishonesty concerning the reported progress of the war in Vietnam gravely eroded the public's previous tendency to put its trust in the word of USG officials. Evidence published in 1971 had demonstrated "systemized abuse of power" by J. Edgar Hoover, the FBI director.[367] The September 1973 overthrow of a democratically elected government in Chile ultimately revealed earlier CIA involvement there.[368] Other factors contributed to the political unease, e.g., the prevalence of conspiracy theories about the Kennedy assassination, and the emergence of whistleblowers. Accordingly, the Central Intelligence Agency, which was tangentially involved in Watergate,[369] and which had been directly engaged in the Vietnam War from the beginning,[370] became a subject of Congressional inquiry and media interest. Helms, of course, had served as head of the CIA, 1965–73. Eventually the process of scrutiny opened a pandora's box of questionable CIA secret activities.[371]

First, the Senate, in order to investigate charges of political malfeasance in the 1972 presidential election,[372] had created the select Watergate Committee, chaired by Senator Sam Ervin. Later, independent press discovery of the CIA's domestic spying, (Operation Chaos), created national headlines.[373] Thereafter, a long list of questionable CIA activities surfaced which caught the public's attention, and were nicknamed the family jewels. Both the Senate, (January 1975), and the House, (February 1975), created select committees to investigate intelligence matters. Senator Frank Church headed one, and Representative Otis Pike headed the other. In an effort to head off such inquiries, President Gerald Ford had created a Commission chaired by Vice President Nelson Rockefeller, whose seminal interest was the CIA's recent foray into collecting intelligence on Americans.[374][375][376] 1975 would become known as the "Year of Intelligence".[377]

Before Congress

Helms testified in appearances before Congress many times during his long career.[378] After he left the CIA in 1973, however, he entered an extraordinary period in which he was frequently called to testify before Congressional committees. While serving as ambassador to Iran (1973–1977), Helms was required to travel from Tehran to Washington sixteen times, thirteen in order to give testimony "before various official bodies of investigation" including the President's Rockefeller Commission. Among the Congressional committee hearings where Helms appeared were the Senate Watergate, the Senate Church,[379] the Senate Intelligence, the Senate Foreign Relations, the Senate Armed Services, the House Pike, the House Armed Services, and the House Foreign Affairs.[380][381]