Gondor

| Gondor | |

|---|---|

| J. R. R. Tolkien's legendarium location | |

Coat of arms bearing the white tree, Nimloth the fair | |

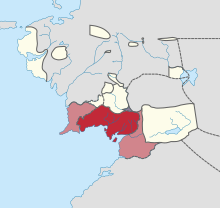

Gondor (red) within Middle-earth, T.A. 3019 | |

| First appearance | The Lord of the Rings |

| In-universe information | |

| Other name(s) | The South-kingdom |

| Type | southern Númenórean realm in exile |

| Ruler | Kings of Gondor; Stewards of Gondor |

| Location | northwest Middle-earth |

| Capital | Osgiliath, then Minas Tirith |

| Founder | Isildur and Anárion |

Gondor is a fictional kingdom in J. R. R. Tolkien's writings, described as the greatest realm of Men in the west of Middle-earth at the end of the Third Age. The third volume of The Lord of the Rings, The Return of the King, is largely concerned with the events in Gondor during the War of the Ring and with the restoration of the realm afterward. The history of the kingdom is outlined in the appendices of the book.

According to the narrative, Gondor was founded by the brothers Isildur and Anárion, exiles from the downfallen island kingdom of Númenor. Along with Arnor in the north, Gondor, the South-kingdom, served as a last stronghold of the Men of the West. After an early period of growth, Gondor gradually declined as the Third Age progressed, being continually weakened by internal strife and conflict with the allies of the Dark Lord Sauron. The kingdom's ascendancy was restored only with Sauron's final defeat and the crowning of Aragorn.

Based upon early conceptions, the history and geography of Gondor were developed in stages as Tolkien extended his legendarium while writing of The Lord of the Rings. Critics have noted the contrast between the cultured but lifeless Stewards of Gondor, and the simple but vigorous leaders of the Kingdom of Rohan, modelled on Tolkien's favoured Anglo-Saxons. Scholars have noted parallels between Gondor and the Normans, Ancient Rome, the Vikings, the Goths, the Langobards, and the Byzantine Empire.

Literature

Fictional etymology

Tolkien intended the name Gondor to be Sindarin for "land of stone".[T 1][T 2] This is echoed in the text of The Lord of the Rings by the name for Gondor among the Rohirrim, Stoningland.[T 3] Tolkien's early writings suggest that this was a reference to the highly developed masonry of Gondorians in contrast to their rustic neighbours.[T 4] This view is supported by the Drúedain terms for Gondorians and Minas Tirith—Stonehouse-folk and Stone-city.[T 5] Tolkien denied that the name Gondor had been inspired by the ancient Ethiopian citadel of Gondar, stating that the root Ond went back to an account he had read as a child mentioning ond ("stone") as one of only two words known of the pre-Celtic languages of Britain.[T 6] Gondor is also called the South-kingdom or Southern Realm, and together with Arnor as the Númenórean Realms in Exile. Researchers Wayne G. Hammond and Christina Scull have proposed a Quenya translation of Gondor: Ondonórë.[1] The Men of Gondor are nicknamed "Tarks" (from Quenya tarkil "High Man", Numenorean)[2] by the orcs of Mordor.[T 7]

Fictional geography

Country

Gondor's geography is illustrated in the maps for The Lord of the Rings and Unfinished Tales made by Christopher Tolkien on the basis of his father's sketches, and geographical accounts in The Rivers and Beacon-Hills of Gondor, Cirion and Eorl, and The Lord of the Rings. Gondor lies in the west of Middle-earth, on the northern shores of Anfalas[T 8][T 9] and the Bay of Belfalas[T 10] with the great port of Pelargir near the river Anduin's delta in the fertile[T 11] and populous[T 9] region of Lebennin,[T 12] stretching up to the White Mountains (Sindarin: Ered Nimrais, "Mountains of White Horns"). Near the mouths of Anduin was the island of Tolfalas.[T 13]

To the north-west of Gondor lies Arnor; to the north, Gondor is neighboured by Wilderland and Rohan; to the north-east, by Rhûn; to the east, by Mordor; to the south, by the deserts of northern Harad. To the west lies the Great Sea. Gondor's land area was estimated by Karen Wynn Fonstad from Tolkien's maps at 716,426 square miles (1,855,530 km2).[3]

The wide land to the west of Rohan was Enedwaith; in some of Tolkien's writings it is part of Gondor, in others not.[T 14][T 15][T 16][T 17] The hot and dry region of South Gondor was by the time of the War of the Rings "a debatable and desert land", contested by the men of Harad.[T 12]

The region of Lamedon and the uplands of the prosperous Morthond, with the desolate Hill of Erech,[T 18] lay to the south of the White Mountains, while the populous[T 3] valleys of Lossarnach were just south of Minas Tirith. Ringló Vale lay between Lamedon and Lebennin.[T 19]

The regions of Anórien, with its capital Minas Anor, and Calenardhon, with fortresses at Isengard[T 17][T 20] and Helm's Deep, lie to the north of the White Mountains. Calenardhon was granted independence as the kingdom of Rohan. To the northeast, by the river Anduin, are the Emyn Muil, with watchtowers on the hills of Amon Hen and Amon Lhaw on opposite banks of the river, and the Gates of Argonath at the northern entrance into the straits of Anduin as a warning to trespassers. Further down the river are the hills of Emyn Arnen.

Capital, Minas Tirith

The capital, Minas Tirith, lay at the eastern end of the White Mountains, built around a shoulder of Mount Mindolluin. It had seven walls, the gates facing alternately somewhat north or south, so the main street up to the citadel wound in zigzags up the hill, each time passing through a tunnel in the central spur of rock. In the citadel, atop the spur, were the Court of the Fountain with the White Tree and the White Tower. This was the seat of the Kings or Stewards of Gondor. Behind the tower, reached from the sixth level, was a saddle leading to the necropolis of the Kings and Stewards.[a] Tolkien's map-notes for the illustrator Pauline Baynes indicate that the city had the latitude of Ravenna, a city on the Mediterranean sea, though it lay "900 miles east of Hobbiton more near Belgrade".[4][5][b] The Warning beacons of Gondor were atop a line of foothills running back west from Minas Tirith towards Rohan.

Fictional history

Pre-Númenórean

The first people in the region were the Drúedain, a hunter-gatherer people of Men who arrive in the First Age. They were pushed aside by later settlers and came to live in the pine-woods of the Druadan Forest[T 5] by the north-eastern White Mountains.[T 21] The next people settled in the White Mountains, and became known as the Men of the Mountains. They built a megalithic subterranean complex at Dunharrow, later known as the Paths of the Dead, which extended through the mountain-range from north to south.[T 11] They became subject to Sauron in the Dark Years. Fragments of pre-Númenórean languages survive in later ages in place-names such as Erech, Arnach, and Umbar.[T 22]

Númenórean kingdom

The shorelands of Gondor were widely colonized by the Númenóreans from the middle of the Second Age, especially by Elf-friends loyal to Elendil.[T 23] His sons Isildur and Anárion landed in Gondor after the drowning of Númenor, and co-founded the Kingdom of Gondor. Isildur brought with him a seedling of Nimloth the fair, the white tree from Númenór, and it appeared on the coat of arms of Gondor. Elendil, who founded the Kingdom of Arnor to the north, was held to be the High King of all the lands of the Dúnedain.[T 15] Within the South-kingdom, the hometowns of Isildur and Anárion were Minas Ithil and Minas Tirith respectively, and the capital city was Osgiliath.[T 15]

Sauron survived the destruction of Númenor and secretly returned to his realm of Mordor, soon launching a war against the Númenórean kingdoms. He captured Minas Ithil, but Isildur escaped by ship to Arnor; meanwhile, Anárion was able to defend Osgiliath.[T 23] Elendil and the Elven-king Gil-galad formed the Last Alliance of Elves and Men, and together with Isildur and Anárion, they besieged and defeated Mordor.[T 23] Sauron was overthrown; but the One Ring that Isildur took from him was not destroyed, and thus Sauron continued to exist.[T 24]

Both Elendil and Anárion were killed in the war, so Isildur conferred rule of Gondor upon Anárion's son Meneldil, retaining suzerainty over Gondor as High King of the Dúnedain. Isildur and his three elder sons were ambushed and killed by Orcs in the Gladden Fields. Isildur's remaining son Valandil did not attempt to claim his father's place as Gondor's monarch; the kingdom is ruled solely by Meneldil and his descendants until their line dies out.[T 24]

Third Age, under the Stewards

During the early years of the Third Age, Gondor was victorious and wealthy, and kept a careful watch on Mordor, but the peace ended with Easterling invasions.[T 26] Gondor established a powerful navy and captured the southern port of Umbar from the Black Númenóreans,[T 26] becoming very rich.[T 15] As time went by, Gondor neglected the watch on Mordor. There was a civil war, giving Umbar the opportunity to declare independence.[T 26] The kings of Harad grew stronger, leading to fighting in the south.[T 27] With a Great Plague the population began a steep decline.[T 26] The capital was moved from Osgiliath to the less affected Minas Anor and evil creatures returned to the mountains bordering Mordor. There was war with the Easterling Wainriders, and Gondor lost its line of kings.[T 28] The Ringwraiths captured and occupied Minas Ithil[T 23] which became Minas Morgul, the Tower of Sorcery. Minas Anor was renamed Minas Tirith, the Tower of Guard.[T 29][T 23][T 15] Without kings, Gondor was ruled by stewards for many generations, father to son; despite their exercise of power and hereditary status, they were never accepted as kings, or sat in the high throne.[T 30][d] After several attacks by evil forces the province of Ithilien[T 9] and the city of Osgiliath were abandoned.[T 15][T 26] Later the forces of Gondor, led by Aragorn under an alias, attacked Umbar and destroyed the Corsair fleet, allowing Denethor II to devote his attention to Mordor.[T 25][8]

War of the Ring and restoration

Denethor sent his son Boromir to Rivendell for advice as war loomed. There, Boromir attended the Council of Elrond, saw the One Ring, and suggested it be used as a weapon to save Gondor. Elrond rebuked him, explaining the danger of such use, and instead, the hobbit Frodo was made ring-bearer, and a Fellowship, including Boromir, was sent on a quest to destroy the Ring.[T 31] Growing in strength, Sauron attacked Osgiliath, forcing the defenders to leave, destroying the last bridge across the Anduin behind them. Minas Tirith then faced direct land attack from Mordor, combined with naval attack by the Corsairs of Umbar. The hobbits Frodo and Sam travelled through Ithilien, and were captured by Faramir, Boromir's brother, who held them at the hidden cave of Henneth Annûn, but aided them to continue their quest.[T 32] Aragorn summoned the Dead of Dunharrow to destroy the forces from Umbar, freeing men from the southern provinces of Gondor such as Dol Amroth[T 9][T 10] to come to the aid of Minas Tirith. Gondor, with the Riders of Rohan as cavalry, defeated the army of Mordor in the Battle of the Pelennor Fields. Aragorn led a smaller army to the Black Gate of Mordor to distract Sauron from the hobbits' quest to destroy the One Ring in Mount Doom. The hobbits succeeded, and Sauron was defeated. The war and the Third Age over, Aragorn was crowned King of both Gondor and Arnor, the sister kingdom in the north.[T 20][T 27][T 33][T 34]

Concept and creation

Tolkien's original thoughts about the later ages of Middle-earth are outlined in his first sketches for the legend of Númenor made in the mid-1930s, and already contain conceptions resembling that of Gondor.[T 35] The appendices to The Lord of the Rings were brought to a finished state in 1953–54, but a decade later, during preparations for the release of the Second Edition, Tolkien elaborated the events that had led to Gondor's civil war, and introduced the regency of Rómendacil II.[T 36] The final development of the history and geography of Gondor took place around 1970, in the last years of Tolkien's life, when he invented justifications for the place-names and wrote full narratives for the stories of Isildur's death and of the battles with the Wainriders and the Balchoth (published in Unfinished Tales).[T 37]

| Situation | Gondor | Rohan |

|---|---|---|

| Leader's behaviour on meeting trespassers |

Faramir, son of Ruling Steward Denethor courteous, urbane, civilised |

Éomer, nephew of King Théoden "compulsively truculent" |

| Ruler's palace | Great Hall of Minas Tirith large, solemn, colourless |

Mead hall of Meduseld, simple, lively, colourful |

| State | "A kind of Rome", subtle, selfish, calculating |

Anglo-Saxon, vigorous |

The critic Tom Shippey compares Tolkien's characterisation of Gondor with that of Rohan. He notes that men from the two countries meet or behave in contrasting ways several times in The Lord of the Rings: when Éomer and his Riders of Rohan twice meet Aragorn's party in the Mark, and when Faramir and his men imprison Frodo and Sam at Henneth Annun in Ithilien. Shippey notes that while Éomer is "compulsively truculent", Faramir is courteous, urbane, civilised: the people of Gondor are self-assured, and their culture is higher than that of Rohan. The same is seen, Shippey argues, in the comparison between the mead hall of Meduseld in Rohan, and the great hall of Minas Tirith in Gondor. Meduseld is simple, but brought to life by tapestries, a colourful stone floor, and the vivid picture of the rider, his bright hair streaming in the wind, blowing his horn. The Steward Denethor's hall is large and solemn, but dead, colourless, in cold stone. Rohan is, Shippey suggests, the "bit that Tolkien knew best",[9] Anglo-Saxon, full of vigour; Gondor is "a kind of Rome", over-subtle, selfish, calculating.[9]

The critic Jane Chance Nitzsche contrasts the "good and bad Germanic lords Théoden and Denethor", noting that their names are almost anagrams. She writes that both men receive the allegiance of a hobbit, but very differently: Denethor, Steward of Gondor, undervalues Pippin because he is small, and binds him with a formal oath, whereas Théoden, King of Rohan, treats Merry with love, which the hobbit responds to.[10]

Influences

The scholar of Germanic studies Sandra Ballif Straubhaar notes in the J.R.R. Tolkien Encyclopedia that readers have debated the real-world prototypes of Gondor. She writes that like the Normans, their founders the Numenoreans arrived "from across the sea", and that Prince Imrahil's armour with a "burnished vambrace" recalls late-medieval plate armour. Against this theory, she notes Tolkien's direction of readers to Egypt and Byzantium. Recalling that Tolkien located Minas Tirith at the latitude of Florence, she states that "the most striking similarities" are with ancient Rome. She identifies several parallels: Aeneas, from Troy, and Elendil, from Numenor, both survive the destruction of their home countries; the brothers Romulus and Remus found Rome, while the brothers Isildur and Anárion found the Numenorean kingdoms in Middle-earth; and both Gondor and Rome experienced centuries of "decadence and decline".[8]

The scholar of fantasy and children's literature Dimitra Fimi draws a parallel between the seafaring Numenoreans and the Vikings of the Norse world, noting that in The Lost Road and Other Writings, Tolkien describes their ship-burials,[T 38] matching those in Beowulf and the Prose Edda.[11] She notes that Boromir is given a boat-funeral in The Two Towers.[T 39][11] Fimi further compares the helmet and crown of Gondor with the romanticised "headgear of the Valkyries", despite Tolkien's denial of a connection with Wagner's Ring cycle, noting the "likeness of the wings of a sea-bird"[T 40] in his description of Aragorn's coronation, and his drawing of the crown in an unused dust jacket design.[T 41][11]

| Situation | Gondor | Byzantine Empire |

|---|---|---|

| Older state echoed | Elendil's unified kingdom | Roman Empire |

| Weaker sister kingdom | Arnor, the Northern kingdom | Western Roman Empire |

| Powerful enemies to East and South |

Easterlings, Haradrim, Mordor |

Persians, Arabs, Turks |

| Final siege from the East | Survives | Falls |

The classical scholar Miryam Librán-Moreno writes that Tolkien drew heavily on the general history of the Goths, Langobards and the Byzantine Empire, and their mutual struggle. Historical names from these peoples were used in drafts or the final concept of the internal history of Gondor, such as Vidumavi, wife of king Valacar (in Gothic).[12] The Byzantine Empire and Gondor were both, in Librán-Moreno's view, only echoes of older states (the Roman Empire and the unified kingdom of Elendil), yet each proved to be stronger than their sister-kingdoms (the Western Roman Empire and Arnor, respectively). Both realms were threatened by powerful eastern and southern enemies: the Byzantines by the Persians and the Muslim armies of the Arabs and the Turks, as well as the Langobards and Goths; Gondor by the Easterlings, the Haradrim, and the hordes of Sauron. Both realms were in decline at the time of a final, all-out siege from the East; however, Minas Tirith survived the siege whereas Constantinople did not.[12] In a 1951 letter, Tolkien himself wrote about "the Byzantine City of Minas Tirith."[13]

Tolkien visited the Malvern Hills with C. S. Lewis,[14][15] and recorded excerpts from The Hobbit and The Lord of the Rings in Malvern in 1952, at George Sayer's home.[16] Sayer wrote that Tolkien relived the book as they walked, comparing the Malvern Hills to the White Mountains of Gondor.[15]

-

Sandra Ballif Straubhaar notes that in Roman legend, Aeneas escapes the ruin of Troy, while Elendil escapes that of Numenor.[8] Painting Aeneas flees burning Troy by Federico Barocci, 1598

-

Dimitra Fimi compares Gondor's bird-winged helmet-crown to the romanticised headgear of the Valkyries. Illustration for The Rhinegold and the Valkyrie by Arthur Rackham, 1910[11]

-

The Malvern Hills may have inspired Tolkien to create parts of the White Mountains.[14]

In film

Gondor as it appeared in Peter Jackson's film adaptation of The Lord of the Rings has been compared to the Byzantine Empire.[18] The production team noted this in DVD commentary, explaining their decision to include Byzantine domes into Minas Tirith's architecture and to have civilians wear Byzantine-styled clothing.[19] However, the appearance and structure of the city was based upon the inhabited tidal island and abbey of Mont Saint-Michel, France.[17] In the films, the towers of the city, designed by the artist Alan Lee, are equipped with trebuchets.[20] The film critic Roger Ebert called the city a "spectacular achievement". He praised the filmmakers' ability to blend digital and real sets.[21]

Notes

- ^ Map #40 in Barbara Strachey's Journeys of Frodo is a plan of Minas Tirith. Pages 138&139 in Karen Wynn Fonstad's revised The Atlas of Middle-earth show a different plan of the city. The only maps by Tolkien are sketches.

- ^ The Tolkien scholar Judy Ann Ford writes that there is also an architectural connection with Ravenna in Pippin's description of the great hall of Denethor, which in her view suggests a Germanic myth of a restored Roman Empire.[6]

- ^ The seal of the stewards consisted of the three letters: R.ND.R (standing for Arandur, king's servant), surmounted by three stars.[T 25]

- ^ Boromir asks his father Denethor how many centuries it would take for a steward to become a king. Denethor replies "Few years, maybe, in other places of less royalty. In Gondor ten thousand years would not suffice."[T 30] Shippey reads this as a reproach to Shakespeare's Macbeth, noting that in Scotland, and in Britain, a Stewart/Steward like James I of England (James VI of Scotland) could metamorphose into a king.[7]

References

Primary

- This list identifies each item's location in Tolkien's writings.

- ^ Return of the King, Appendix F, "Of Men"

- ^ Etymologies, entries GOND-, NDOR-

- ^ a b Return of the King, book 5 ch. 6 "The Battle of the Pelennor Fields"

- ^ Return of the Shadow, ch. 22 "New Uncertainties and New Projections"

- ^ a b Return of the King, book 5 ch. 5 "The Ride of the Rohirrim"

- ^ Carpenter 1981, #324

- ^ The Return of the King, "The Tower of Cirith Ungol"

- ^ Etymologies, entries ÁNAD-, PHÁLAS-, TOL2-

- ^ a b c d Return of the King, book 5 ch. 1 "Minas Tirith"

- ^ a b Unfinished Tales, part 2 ch. 4 "History of Galadriel and Celeborn": "Amroth and Nimrodel"

- ^ a b Return of the King, book 5 ch. 9 "The Last Debate"

- ^ a b Unfinished Tales, map of the West of Middle-earth

- ^ Peoples, ch. 6 "The Tale of Years of the Second Age"

- ^ Peoples, ch. 10 "Of Dwarves and Men", and notes 66, 76

- ^ a b c d e f Return of the King, Appendix A, I (iv)

- ^ Unfinished Tales, part 2 ch. 4 "History of Galadriel and Celeborn"; Appendices C and D

- ^ a b Unfinished Tales, "The Battles of the Fords of Isen", Appendix (ii)

- ^ Return of the King, book 1 ch. 2 "The Passing of the Grey Company"

- ^ Return of the King, map of Gondor

- ^ a b Return of the King, Appendix A, II

- ^ Return of the King, book 6 ch. 6 "Many Partings"

- ^ Return of the King, Appendix F part 1

- ^ a b c d e Silmarillion, "Of the Rings of Power and the Third Age"

- ^ a b Unfinished Tales, part 3 ch. 1 "Disaster of the Gladden Fields"

- ^ a b Unfinished Tales & see note 25, part 3 ch. 2 "Cirion and Eorl"

- ^ a b c d e Return of the King, Appendix B "The Third Age"

- ^ a b Peoples, ch. 7 "The Heirs of Elendil"

- ^ Unfinished Tales, part 3 ch. 2 "Cirion and Eorl", (i)

- ^ Return of the King, book 5 ch. 8 "The Houses of Healing"; book 6 ch. 5 "The Steward and the King"

- ^ a b Two Towers, book 4, ch. 5 "The Window on the West"

- ^ Fellowship of the Ring, book 2 ch. 2 "The Council of Elrond"

- ^ Two Towers, book 4 ch. 5 "The Window on the West"

- ^ Peoples, ch. 8 "The Tale of Years of the Third Age"

- ^ Carpenter 1981, #256, #338

- ^ Lost Road, ch. 2 "The Fall of Númenor"

- ^ Peoples, ch. 9 "The Making of Appendix A". Letter c in names is used for original k.

- ^ Peoples, ch. 13 "Last Writings"

- ^ The Lost Road and Other Writings, ch. 2 "The Fall of Numenor"

- ^ Two Towers, book 3, ch. 1 "The Departure of Boromir"

- ^ Return of the King, book 6, ch. 5 "The Steward and the King"

- ^ The Winged Crown of Gondor. Bodleian Library, Oxford, MS. Tolkien Drawings 90, fol. 30.

Secondary

- ^ Hammond & Scull 2005, "The Great River", p. 347

- ^ Parma Eldalamberon XVII, "Words, Phrases and Passages in Various Tongues in The Lord of the Rings" p. 101

- ^ Fonstad, Karen Wynn (1991). The Atlas of Middle-earth. Boston: Houghton Mifflin Harcourt. p. 191. ISBN 0-618-12699-6.

- ^ Flood, Alison (23 October 2015). "Tolkien's annotated map of Middle-earth discovered inside copy of Lord of the Rings". The Guardian.

- ^ "Tolkien annotated map of Middle-earth acquired by Bodleian library". Exeter College, Oxford. 9 May 2016. Retrieved 9 April 2020.

- ^ Ford, Judy Ann (2005). "The White City: The Lord of the Rings as an Early Medieval Myth of the Restoration of the Roman Empire". Tolkien Studies. 2 (1): 53–73. doi:10.1353/tks.2005.0016. ISSN 1547-3163.

- ^ Shippey 2005, p. 206.

- ^ a b c Straubhaar 2007, pp. 248–249.

- ^ a b c d Shippey 2005, pp. 146–149.

- ^ Nitzsche 1980, pp. 119–122.

- ^ a b c d Fimi 2007, pp. 84–99.

- ^ a b c Librán-Moreno, Miryam (2011). "'Byzantium, New Rome!' Goths, Langobards and Byzantium in The Lord of the Rings". In Fisher, Jason (ed.). Tolkien and the Study of his Sources. MacFarland & Co. pp. 84–116. ISBN 978-0-7864-6482-1.

- ^ a b Hammond & Scull 2005, p. 570

- ^ a b Duriez 1992, p. 253

- ^ a b Sayer 1979

- ^ Carpenter 1977

- ^ a b Morrison, Geoffrey (27 June 2014). "The real-life Minas Tirith from 'Lord of the Rings': A tour of Mont Saint-Michel". CNET.

- ^ Puig, Claudia (24 February 2004). "With third film, 'Rings' saga becomes a classic". USA Today.

In the third installment, for example, Minas Tirith, a seven-tiered city of kings, looks European, Byzantine and fantastical at the same time.

- ^ The Lord of the Rings: The Return of the King (special extended DVD ed.). December 2004.

- ^ Russell, Gary (2004). The Art of The Lord of the Rings. Houghton Mifflin Harcourt. pp. 103-105. ISBN 0-618-51083-4.

- ^ Ebert, Roger (17 December 2003). "Lord of the Rings: The Return of the King". Chicago Sun-Times.

Sources

- Carpenter, Humphrey (1977). J. R. R. Tolkien: A Biography. New York: Ballantine Books. ISBN 978-0-04-928037-3.

- Duriez, Colin (1992). The J.R.R. Tolkien handbook. Baker Book House. p. 253. ISBN 0801030145.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Carpenter, Humphrey, ed. (2023) [1981]. The Letters of J. R. R. Tolkien: Revised and Expanded Edition. New York: Harper Collins. ISBN 978-0-35-865298-4.

- Fimi, Dimitra (2007). Clark, David; Phelpstead, Carl (eds.). Tolkien and Old Norse Antiquity (PDF). Viking Society for Northern Research: University College London. pp. 84–99.

{{cite book}}:|work=ignored (help); Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Hammond, Wayne G.; Scull, Christina (2005). The Lord of the Rings: A Reader's Companion. London: HarperCollins. ISBN 0-00-720907-X.

- Nitzsche, Jane Chance (1980) [1979]. Tolkien's Art. Papermac. ISBN 0-333-29034-8.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Sayer, George (1979) [August 1952 recording]. Liner notes to J.R.R. Tolkien Reads and Sings his the Hobbit and the Fellowship of the Ring. Caedmon.

{{cite AV media}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Shippey, Tom (2005) [1982]. The Road to Middle-Earth (Third ed.). Grafton (HarperCollins). ISBN 978-0261102750.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Straubhaar, Sandra Ballif (2007). "Gondor". In Drout, Michael D. C. (ed.). J. R. R. Tolkien Encyclopedia: Scholarship and Critical Assessment. Routledge. pp. 248–249. ISBN 978-0-415-96942-0.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Tolkien, J. R. R. (1954a). The Fellowship of the Ring. The Lord of the Rings. Boston: Houghton Mifflin. OCLC 9552942.

- Tolkien, J. R. R. (1954). The Two Towers. The Lord of the Rings. Boston: Houghton Mifflin. OCLC 1042159111.

- Tolkien, J. R. R. (1955). The Return of the King. The Lord of the Rings. Boston: Houghton Mifflin. OCLC 519647821.

- Tolkien, J. R. R. (1977). Christopher Tolkien (ed.). The Silmarillion. Boston: Houghton Mifflin. ISBN 978-0-395-25730-2.

- Tolkien, J. R. R. (1980). Christopher Tolkien (ed.). Unfinished Tales. Boston: Houghton Mifflin. ISBN 978-0-395-29917-3.

- Tolkien, J. R. R. (1987). Christopher Tolkien (ed.). The Lost Road and Other Writings. Boston: Houghton Mifflin. The Etymologies, pp. 341–400. ISBN 0-395-45519-7.

- Tolkien, J. R. R. (1988). Christopher Tolkien (ed.). The Return of the Shadow. Boston: Houghton Mifflin. ISBN 978-0-395-49863-7.

- Tolkien, J. R. R. (1996). Christopher Tolkien (ed.). The Peoples of Middle-earth. Boston: Houghton Mifflin. ISBN 978-0-395-82760-4.

Further reading

- Ford, Judy Ann (2005). "The White City: The Lord of the Rings as an Early Medieval Myth of the Restoration of the Roman Empire". Tolkien Studies. 2: 53–73. doi:10.1353/tks.2005.0016.

- Straubhaar, Sandra Ballif (2004). "Myth, Late Roman History and Multiculturalism in Tolkien's Middle-earth". In Chance, Jane (ed.). Tolkien and the Invention of Myth: A Reader. University Press of Kentucky. pp. 101–118. ISBN 0-8131-2301-1.

![Sandra Ballif Straubhaar notes that in Roman legend, Aeneas escapes the ruin of Troy, while Elendil escapes that of Numenor.[8] Painting Aeneas flees burning Troy by Federico Barocci, 1598](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/f/f7/Aeneas%27_Flight_from_Troy_by_Federico_Barocci.jpg/175px-Aeneas%27_Flight_from_Troy_by_Federico_Barocci.jpg)

![Dimitra Fimi compares Gondor's bird-winged helmet-crown to the romanticised headgear of the Valkyries. Illustration for The Rhinegold and the Valkyrie by Arthur Rackham, 1910[11]](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/e/eb/Romanticised_headgear_of_the_Valkyries.jpg/175px-Romanticised_headgear_of_the_Valkyries.jpg)

![Tolkien called Minas Tirith a "Byzantine City" (Constantinople shown).[13]](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/f/fa/Constantinople_1453.jpg/116px-Constantinople_1453.jpg)

![The Malvern Hills may have inspired Tolkien to create parts of the White Mountains.[14]](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/5/59/Malvern_Hills_in_June_2005.JPG/175px-Malvern_Hills_in_June_2005.JPG)