GW170817

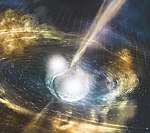

The GW170817 signal as measured by the LIGO and Virgo gravitational wave detectors. Signal is invisible in the Virgo data | |

| Event type | Gravitational wave event |

|---|---|

| Instrument | LIGO, Virgo |

| Right ascension | 13h 09m 48.08s[1] |

| Declination | −23° 22′ 53.3″[1] |

| Epoch | J2000.0 |

| Distance | 40 megaparsecs (130 Mly) |

| Redshift | 0.0099 |

| Other designations | GW170817 |

| | |

GW 170817 was a gravitational wave (GW) signal observed by the LIGO and Virgo detectors on 17 August 2017, originating from the shell elliptical galaxy NGC 4993. The GW was produced by the last minutes of two neutron stars spiralling closer to each other and finally merging, and is the first GW observation which has been confirmed by non-gravitational means.[1][2] Unlike the five previous GW detections, which were of merging black holes not expected to produce a detectable electromagnetic signal,[3][4][5][a] the aftermath of this merger was also seen by 70 observatories on 7 continents and in space, across the electromagnetic spectrum, marking a significant breakthrough for multi-messenger astronomy.[1][7][8][9][10] The discovery and subsequent observations of GW 170817 were given the Breakthrough of the Year award for 2017 by the journal Science.[11][12]

The gravitational wave signal, designated GW 170817, had a duration of approximately 100 seconds, and shows the characteristics in intensity and frequency expected of the inspiral of two neutron stars. Analysis of the slight variation in arrival time of the GW at the three detector locations (two LIGO and one Virgo) yielded an approximate angular direction to the source. Independently, a short (~2 seconds' duration) gamma-ray burst, designated GRB 170817A, was detected by the Fermi and INTEGRAL spacecraft beginning 1.7 seconds after the GW merger signal.[1][13][14] These detectors have very limited directional sensitivity, but indicated a large area of the sky which overlapped the gravitational wave position. It has been a long-standing hypothesis that short gamma-ray bursts are caused by neutron star mergers.

An intense observing campaign then took place to search for the expected emission at optical wavelengths. An astronomical transient designated AT 2017gfo (originally, SSS 17a) was found, 11 hours after the gravitational wave signal, in the galaxy NGC 4993[15] during a search of the region indicated by the GW detection. It was observed by numerous telescopes, from radio to X-ray wavelengths, over the following days and weeks, and was shown to be a fast-moving, rapidly-cooling cloud of neutron-rich material, as expected of debris ejected from a neutron-star merger.

In October 2018, astronomers reported that GRB 150101B, a gamma-ray burst event detected in 2015, may be analogous to GW 170817. The similarities between the two events, in terms of gamma ray, optical, and x-ray emissions, as well as to the nature of the associated host galaxies, are considered "striking", and this remarkable resemblance suggests the two separate and independent events may both be the result of the merger of neutron stars, and both may be a hitherto-unknown class of kilonova transients. Kilonova events, therefore, may be more diverse and common in the universe than previously understood, according to the researchers.[16][17][18][19] In retrospect, GRB 160821B, another gamma-ray burst event is now construed to be another kilonova,[20] by its resemblance of its data to GRB 170817A,[21] part of the multi-messenger now denoted GW170817.

Announcement

It's the first time that we've observed a cataclysmic astrophysical event in both gravitational waves and electromagnetic waves – our cosmic messengers.[22]

The observations were officially announced on 16 October 2017 at press conferences at the National Press Club in Washington, D.C. and at the ESO headquarters in Garching bei München in Germany.[13][14][15]

Some information was leaked before the official announcement, beginning on 18 August 2017 when astronomer J. Craig Wheeler of the University of Texas at Austin tweeted "New LIGO. Source with optical counterpart. Blow your sox off!".[5] He later deleted the tweet and apologized for scooping the official announcement protocol. Other people followed up on the rumor, and reported that the public logs of several major telescopes listed priority interruptions in order to observe NGC 4993, a galaxy 40 Mpc (130 Mly) away in the Hydra constellation.[23][24] The collaboration had earlier declined to comment on the rumors, not adding to a previous announcement that there were several triggers under analysis.[25][26]

Gravitational wave detection

The gravitational wave signal lasted for approximately 100 seconds starting from a frequency of 24 hertz. It covered approximately 3,000 cycles, increasing in amplitude and frequency to a few hundred hertz in the typical inspiral chirp pattern, ending with the collision received at 12:41:04.4 UTC.[2]: 2 It arrived first at the Virgo detector in Italy, then 22 milliseconds later at the LIGO-Livingston detector in Louisiana, USA, and another 3 milliseconds later at the LIGO-Hanford detector in the state of Washington, USA. The signal was detected and analyzed by a comparison with a prediction from general relativity defined from the post-Newtonian expansion.[1]: 3

An automatic computer search of the LIGO-Hanford datastream triggered an alert to the LIGO team about 6 minutes after the event. The gamma-ray alert had already been issued at this point (16 seconds post-event),[27] so the timing near-coincidence was automatically flagged. The LIGO/Virgo team issued a preliminary alert (with only the crude gamma-ray position) to astronomers in the follow-up teams at 40 minutes post-event.[28][29]

Sky localisation of the event requires combining data from the three interferometers; this was delayed by two problems. The Virgo data were delayed by a data transmission problem, and the LIGO Livingston data were contaminated by a brief burst of instrumental noise a few seconds prior to event peak, but persisting parallel to the rising transient signal in the lowest frequencies. These required manual analysis and interpolation before the sky location could be announced about 4.5 hours post-event.[30][29] The three detections localized the source to an area of 31 square degrees in the southern sky at 90% probability. More detailed calculations later refined the localization to within 28 square degrees.[28][2] In particular, the absence of a clear detection by the Virgo system implied that the source was in one of Virgo's blind spots; this absence of signal in Virgo data contributed to considerably reduce the source containment area.[31]

Gamma ray detection

The first electromagnetic signal detected was GRB 170817A, a short gamma-ray burst, detected 1.74±0.05 s after the merger time and lasting for about 2 seconds.[14][23][1]: 5

GRB 170817A was discovered by the Fermi Gamma-ray Space Telescope, with an automatic alert issued just 14 seconds after the GRB detection. After the LIGO/Virgo circular 40 minutes later, manual processing of data from the INTEGRAL gamma-ray telescope also detected the same GRB. The difference in arrival time between Fermi and INTEGRAL helped to improve the sky localization.

This GRB was relatively faint given the proximity of the host galaxy NGC 4993, possibly due to its jets not being pointed directly toward Earth, but rather at an angle of about 30 degrees to the side.[15][32]

Electromagnetic follow-up

A series of alerts to other astronomers were issued, beginning with a report of the gamma-ray detection and single-detector LIGO trigger at 13:21 UTC, and a three-detector sky location at 17:54 UTC.[28] These prompted a massive search by many survey and robotic telescopes. In addition to the expected large size of the search area (about 150 times the area of a full moon), this search was challenging because the search area was near the Sun in the sky and thus visible for at most a few hours after dusk for any given telescope.[29]

In total six teams (One-Meter, Two Hemispheres (1M2H), DLT40, VISTA, Master, DECam, Las Cumbres Observatory (LCO) Chile) imaged the same new source independently in a 90-minute interval.[1]: 5 The first to detect optical light associated with the collision was the 1M2H team running the Swope Supernova Survey, which found it in an image of NGC 4993 taken 10 hours and 52 minutes after the GW event[14][1][33] by the 1-meter diameter (3.3 ft) Swope Telescope operating in the near infrared at Las Campanas Observatory, Chile. They were also the first to announce it, naming their detection SSS 17a in a circular issued 12h26m post-event. The new source was later given an official International Astronomical Union (IAU) designation of AT 2017gfo.

The 1M2H team surveyed all galaxies in the region of space predicted by the gravitational wave observations, and identified a single new transient.[32][33] By identifying the host galaxy of the merger, it is possible to provide an accurate distance consistent with that based on gravitational waves alone.[1]: 5

The detection of the optical and near-infrared source provided a huge improvement in localisation, reducing the uncertainty from several degrees to 0.0001 degree; this enabled many large ground and space telescopes to follow up the source over the following days and weeks. Within hours after localization, many additional observations were made across the infrared and visible spectrum.[33] Over the following days, the color of the optical source changed from blue to red as the source expanded and cooled.[32]

Numerous optical and infrared spectra were observed; early spectra were nearly featureless, but after a few days, broad features emerged indicative of material ejected at roughly 10 percent of light speed. There are multiple strong lines of evidence that AT 2017gfo is indeed the aftermath of GW 170817: The colour evolution and spectra are dramatically different from any known supernova. The distance of NGC 4993 is consistent with that independently estimated from the GW signal. No other transient has been found in the GW sky localisation region. Finally, various archive images pre-event show nothing at the location of AT 2017gfo, ruling out a foreground variable star in the Milky Way.[1]

The source was detected in the ultraviolet (but not in X-rays) 15.3 hours after the event by the Swift Gamma-Ray Burst Mission.[1]: 6 After initial lack of X-ray and radio detections, the source was detected in X-rays 9 days later by the Chandra X-ray Observatory,[34][35] and 16 days later in the radio by the Karl G. Jansky Very Large Array (VLA) in New Mexico.[15] More than 70 observatories covering the electromagnetic spectrum observed the source.[15]

The radio and X-ray light continued to rise for several months after the merger,[36] and have been represented to be diminishing.[37] In September 2019, astronomers reported obtaining an optical image of GW170817 [putative] afterglow by the Hubble Space Telescope.[38][39] In March 2020, continued X-ray emission at 5-sigma was observed by the Chandra Observatory 940 days after the merger, demanding further augmentation or refutation of prior models that had previously been supplemented with additional post-hoc interventions.[40]

Other detectors

No neutrinos consistent with the source were found in follow-up searches by the IceCube and ANTARES neutrino observatories and the Pierre Auger Observatory.[2][1] A possible explanation for the non-detection of neutrinos is because the event was observed at a large off-axis angle and thus the outflow jet was not directed towards Earth.[41][42]

Astrophysical origin and products

The gravitational wave signal indicated that it was produced by the collision of two neutron stars[23][24][26][43] with a total mass of 2.82+0.47

−0.09 times the mass of the sun (solar masses)[2] If low spins are assumed, consistent with those observed in binary neutron stars that will merge within a Hubble time, the total mass is 2.74+0.04

−0.01 M☉.

The masses of the component stars have greater uncertainty. The larger (m1) has a 90% chance of being between 1.36 and 2.26 M☉, and the smaller (m2) has a 90% chance of being between 0.86 and 1.36 M☉.[44] Under the low spin assumption, the ranges are 1.36 to 1.60 M☉ for m1 and 1.17 to 1.36 M☉ for m2.

The chirp mass, a directly observable parameter which may be very roughly equated to the geometric mean of the masses, is measured at 1.188+0.004

−0.002 M☉.[44]

The neutron star merger event is thought to result in a kilonova, characterized by a short gamma-ray burst followed by a longer optical "afterglow" powered by the radioactive decay of heavy r-process nuclei. Kilonovae are candidates for the production of half the chemical elements heavier than iron in the Universe.[15] A total of 16,000 times the mass of the Earth in heavy elements is believed to have formed, including approximately 10 Earth masses just of the two elements gold and platinum.[45]

A hypermassive neutron star was believed to have formed initially, as evidenced by the large amount of ejecta (much of which would have been swallowed by an immediately forming black hole). The lack of evidence for emissions being powered by neutron star spin-down, which would occur for longer-surviving neutron stars, suggest it collapsed into a black hole within milliseconds.[46]

Later searches did find evidence of spin-down in the gravitational signal, suggesting a longer-lived neutron star.[47]

Scientific importance

Scientific interest in the event was enormous, with dozens of preliminary papers (and almost 100 preprints[49]) published the day of the announcement, including 8 letters in Science,[15] 6 in Nature, and 32 in a special issue of The Astrophysical Journal Letters devoted to the subject.[7] The interest and effort was global: The paper describing the multi-messenger observations[1] is coauthored by almost 4,000 astronomers (about one-third of the worldwide astronomical community) from more than 900 institutions, using more than 70 observatories on all 7 continents and in space.[5][15]

This may not be the first observed event that is due to a neutron star merger; GRB 130603B was the first plausible kilonova suggested based on follow-up observations of short-hard gamma-ray bursts.[50] It is, however, by far the best observation, making this the strongest evidence to date to confirm the hypothesis that some mergers of binary stars are the cause of short gamma-ray bursts.[1][2]

The event also provides a limit on the difference between the speed of light and that of gravity. Assuming the first photons were emitted between zero and ten seconds after peak gravitational wave emission, the difference between the speeds of gravitational and electromagnetic waves, vGW − vEM, is constrained to between −3×10−15 and +7×10−16 times the speed of light, which improves on the previous estimate by about 14 orders of magnitude.[44][51][b] In addition, it allowed investigation of the equivalence principle (through Shapiro delay measurement) and Lorentz invariance.[2] The limits of possible violations of Lorentz invariance (values of 'gravity sector coefficients') are reduced by the new observations, by up to ten orders of magnitude.[44] GW 170817 also excluded some alternatives to general relativity,[52] including variants of scalar–tensor theory,[53][54][55][56][57][58][59][60] Hořava–Lifshitz gravity,[61][62][63] Dark Matter Emulators[64] and bimetric gravity.[65]

Gravitational wave signals such as GW 170817 may be used as a standard siren to provide an independent measurement of the Hubble constant.[66][67] An initial estimate of the constant derived from the observation is 70.0+12.0

−8.0 (km/s)/Mpc, broadly consistent with current best estimates.[66] Further studies improved the measurement to 70.3+5.3

−5.0 (km/s)/Mpc.[68][69][70] Together with the observation of future events of this kind the uncertainty is expected to reach two percent within five years and one percent within ten years.[71][72]

Electromagnetic observations helped to support the theory that the mergers of neutron stars contribute to rapid neutron capture r-process nucleosynthesis[33] and are significant sources of r-process elements heavier than iron,[1] including gold and platinum, which was previously attributed exclusively to supernova explosions.[45]

In October 2017, Stephen Hawking, in his last broadcast interview, presented the overall scientific importance of GW 170817.[73]

In September 2018, astronomers reported related studies about possible mergers of neutron stars (NS) and white dwarfs (WD): including NS-NS, NS-WD, and WD-WD mergers.[74]

The first identification of r-process elements in a neutron star merger was obtained during a re-analysis of GW170817 spectra.[75] The spectra provided direct proof of strontium production during a neutron star merger. This also provided a direct proof that neutron stars are made of neutron-rich matter.

See also

Notes

- ^ Although acknowledged as unlikely, several mechanisms have been suggested by which a black hole merger could be surrounded by sufficient matter to produce an electromagnetic signal, which astronomers have been searching for.[4][6]

- ^ Previous constraint on the difference between the light speed and the gravitational speed was about ±20%.[51]

References

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p Abbott, B. P.; et al. (LIGO, Virgo and other collaborations) (October 2017). "Multi-messenger Observations of a Binary Neutron Star Merger" (PDF). The Astrophysical Journal. 848 (2): L12. arXiv:1710.05833. Bibcode:2017ApJ...848L..12A. doi:10.3847/2041-8213/aa91c9.

The optical and near-infrared spectra over these few days provided convincing arguments that this transient was unlike any other discovered in extensive optical wide-field surveys over the past decade.

- ^ a b c d e f g Abbott, B. P.; et al. (LIGO Scientific Collaboration & Virgo Collaboration) (October 2017). "GW170817: Observation of Gravitational Waves from a Binary Neutron Star Inspiral" (PDF). Physical Review Letters. 119 (16): 161101. arXiv:1710.05832. Bibcode:2017PhRvL.119p1101A. doi:10.1103/PhysRevLett.119.161101. PMID 29099225.

- ^ Connaughton, Valerie (2016). "Focus on electromagnetic counterparts to binary black hole mergers". The Astrophysical Journal Letters (Editorial).

The follow-up observers sprang into action, not expecting to detect a signal if the gravitational radiation was indeed from a binary black-hole merger. [...] most observers and theorists agreed: the presence of at least one neutron star in the binary system was a prerequisite for the production of a circumbinary disk or neutron star ejecta, without which no electromagnetic counterpart was expected.

- ^ a b Loeb, Abraham (March 2016). "Electromagnetic counterparts to black hole mergers detected by LIGO". The Astrophysical Journal Letters. 819 (2): L21. arXiv:1602.04735. Bibcode:2016ApJ...819L..21L. doi:10.3847/2041-8205/819/2/L21.

Mergers of stellar-mass black holes (BHs) [...] are not expected to have electromagnetic counterparts. [...] I show that the [GW and gamma-ray] signals might be related if the BH binary detected by LIGO originated from two clumps in a dumbbell configuration that formed when the core of a rapidly rotating massive star collapsed.

- ^ a b c Schilling, Govert (16 October 2017). "Astronomers catch gravitational waves from colliding neutron stars". Sky & Telescope.

because colliding black holes don't give off any light, you wouldn't expect any optical counterpart.

- ^ de Mink, S.E.; King, A. (April 2017). "Electromagnetic signals following stellar-mass black hole mergers" (PDF). The Astrophysical Journal Letters. 839 (1): L7. arXiv:1703.07794. Bibcode:2017ApJ...839L...7D. doi:10.3847/2041-8213/aa67f3.

It is often assumed that gravitational-wave (GW) events resulting from the merger of stellar-mass black holes are unlikely to produce electromagnetic (EM) counterparts. We point out that the progenitor binary has probably shed a mass ≳ 10 M☉ during its prior evolution. If even a tiny fraction of this gas is retained in a circum-binary disk, the sudden mass loss and recoil of the merged black hole shocks and heats it within hours of the GW event. Whether the resulting EM signal is detectable is uncertain.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: unflagged free DOI (link) - ^ a b Berger, Edo (16 October 2017). "Focus on the electromagnetic counterpart of the neutron star binary merger GW 170817". The Astrophysical Journal Letters (Editorial). 848 (2).

It is rare for the birth of a new field of astrophysics to be pinpointed to a singular event. This focus issue follows such an event – the neutron star binary merger GW 170817 – marking the first joint detection and study of gravitational waves (GWs) and electromagnetic radiation (EM).

- ^ Landau, Elizabeth; Chou, Felicia; Washington, Dewayne; Porter, Molly (16 October 2017). "NASA missions catch first light from a gravitational-wave event". NASA. Retrieved 16 October 2017.

- ^ Botkin-Kowacki, Eva (16 October 2017). "Neutron star discovery marks breakthrough for 'multi-messenger astronomy'". The Christian Science Monitor. Retrieved 17 October 2017.

- ^ Metzger, Brian D. (16 October 2017). "Welcome to the multi-messenger era! Lessons from a neutron star merger and the landscape ahead". arXiv:1710.05931 [astro-ph.HE].

- ^ "Breakthrough of the year 2017". Science | AAAS. 22 December 2017.

- ^ Cho, Adrian (2017). "Cosmic convergence". Science. 358 (6370): 1520–1521. Bibcode:2017Sci...358.1520C. doi:10.1126/science.358.6370.1520. PMID 29269456.

- ^ a b Overbye, Dennis (16 October 2017). "LIGO detects fierce collision of neutron stars for the first time". The New York Times. Retrieved 16 October 2017.

- ^ a b c d Krieger, Lisa M. (16 October 2017). "A bright light seen across the Universe, proving Einstein right – violent collisions source of our gold, silver". The Mercury News. Retrieved 16 October 2017.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Cho, Adrian (16 October 2017). "Merging neutron stars generate gravitational waves and a celestial light show". Science. doi:10.1126/science.aar2149.

- ^ "All in the family: Kin of gravitational wave source discovered – New observations suggest that kilonovae – immense cosmic explosions that produce silver, gold and platinum – may be more common than thought". University of Maryland. 16 October 2018. Retrieved 17 October 2018 – via EurekAlert!.

- ^ Troja, E.; et al. (16 October 2018). "A luminous blue kilonova and an off-axis jet from a compact binary merger at z = 0.1341". Nature Communications. 9 (4089 (2018)): 4089. arXiv:1806.10624. Bibcode:2018NatCo...9.4089T. doi:10.1038/s41467-018-06558-7. PMC 6191439. PMID 30327476.

- ^ Mohon, Lee (16 October 2018). "GRB 150101B: A distant cousin to GW 170817". NASA. Retrieved 17 October 2018.

- ^ Wall, Mike (17 October 2018). "Powerful cosmic flash is likely another neutron-star merger". Space.com. Retrieved 17 October 2018.

- ^ Troja, E.; Castro-Tirado, A. J.; González, J Becerra; Hu, Y.; Ryan, G. S.; Cenko, S. B.; Ricci, R.; Novara, G.; Sánchez-Rámirez, R.; Acosta-Pulido, J. A.; Ackley, K. D.; Caballero García, M. D.; Eikenberry, S. S.; Guziy, S.; Jeong, S.; Lien, A. Y.; Márquez, I.; Pandey, S. B.; Park, I. H.; Sakamoto, T.; Tello, J. C.; Sokolov, I. V.; Sokolov, V. V.; Tiengo, A.; Valeev, A. F.; Zhang, B. B.; Veilleux, S. (2019). "The afterglow and kilonova of the short GRB 160821B". Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society. 489 (2): 2104. arXiv:1905.01290. Bibcode:2019MNRAS.489.2104T. doi:10.1093/mnras/stz2255.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: unflagged free DOI (link) - ^ Goldstein, A.; Veres, P.; Burns, E.; Briggs, M. S.; Hamburg, R.; Kocevski, D.; Wilson-Hodge, C. A.; Preece, R. D.; Poolakkil, S.; Roberts, O. J.; Hui, C. M.; Connaughton, V.; Racusin, J.; Kienlin, A. von; Canton, T. Dal; Christensen, N.; Littenberg, T.; Siellez, K.; Blackburn, L.; Broida, J.; Bissaldi, E.; Cleveland, W. H.; Gibby, M. H.; Giles, M. M.; Kippen, R. M.; McBreen, S.; McEnery, J.; Meegan, C. A.; Paciesas, W. S.; Stanbro, M. (2017). "An Ordinary Short Gamma-Ray Burst with Extraordinary Implications: Fermi -GBM Detection of GRB 170817A". The Astrophysical Journal. 848 (2): L14. arXiv:1710.05446. Bibcode:2017ApJ...848L..14G. doi:10.3847/2041-8213/aa8f41.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: unflagged free DOI (link) - ^ "LIGO and Virgo make first detection of gravitational waves produced by colliding neutron stars". MIT News. 16 October 2017. Retrieved 23 October 2017.

- ^ a b c Castelvecchi, Davide (August 2017). "Rumours swell over new kind of gravitational-wave sighting". Nature News. doi:10.1038/nature.2017.22482.

- ^ a b McKinnon, Mika (23 August 2017). "Exclusive: We may have detected a new kind of gravitational wave". New Scientist. Retrieved 28 August 2017.

- ^ "A very exciting LIGO-Virgo observing run is drawing to a close August 25". LIGO. 25 August 2017. Retrieved 29 August 2017.

- ^ a b Drake, Nadia (25 August 2017). "Strange stars caught wrinkling spacetime? Get the facts". National Geographic. Retrieved 27 August 2017.

- ^ "GCN notices related to Fermi-GBM alert 524666471". Gamma-ray Burst Coordinates Network. NASA Goddard Space Flight Center. 17 August 2017. Retrieved 19 October 2017.

- ^ a b c "GCN circulars related to LIGO trigger G298048". Gamma-ray Burst Coordinates Network. NASA Goddard Space Flight Center. 17 August 2017. Retrieved 19 October 2017.

- ^ a b c Castelvecchi, Davide (16 October 2017). "Colliding stars spark rush to solve cosmic mysteries". Nature. 550 (7676): 309–310. Bibcode:2017Natur.550..309C. doi:10.1038/550309a. PMID 29052641.

- ^ Berry, Christopher (16 October 2017). "GW170817—The pot of gold at the end of the rainbow". Retrieved 19 October 2017.

- ^ Schilling, Govert A. (January 2018). "Two massive collisions and a Nobel Prize". Sky & Telescope. 135 (1): 10.

- ^ a b c Choi, Charles Q. (16 October 2017). "Gravitational waves detected from neutron star crashes: The discovery explained". Space.com. Purch Group. Retrieved 16 October 2017.

- ^ a b c d Drout, M. R.; et al. (October 2017). "Light curves of the neutron star merger GW 170817 / SSS 17a: Implications for r-process nucleosynthesis". Science. 358 (6370): 1570–1574. arXiv:1710.05443. Bibcode:2017Sci...358.1570D. doi:10.1126/science.aaq0049. PMID 29038375.

- ^ "Chandra :: Photo Album :: GW170817 :: October 16, 2017". chandra.si.edu. Retrieved 16 August 2019.

- ^ "Chandra Makes First Detection of X-rays from a Gravitational Wave Source: Interview with Chandra Scientist Eleonora Nora Troja". chandra.si.edu. Retrieved 16 August 2019.

- ^ "Neutron-star merger creates new mysteries".

- ^ Kaplan, David; Murphy, Tara. "Signals from a spectacular neutron star merger that made gravitational waves are slowly fading away". The Conversation. Retrieved 16 August 2019.

- ^ Morris, Amanda (11 September 2019). "Hubble Captures Deepest Optical Image of First Neutron Star Collision". ScienceDaily.com. Retrieved 11 September 2019.

- ^ Fong, W.; et al. (23 August 2019). "The Optical Afterglow of GW170817: An Off-axis Structured Jet and Deep Constraints on a Globular Cluster Origin". The Astrophysical Journal. 883 (1): L1. arXiv:1908.08046. Bibcode:2019ApJ...883L...1F. doi:10.3847/2041-8213/ab3d9e.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: unflagged free DOI (link) - ^ Troja, E.; et al. (18 March 2020). "ATel#13565 - GW170817: Continued X-ray emission detected with Chandra at 940 days post-merger". The Astronomer's Telegram. Retrieved 19 March 2020.

- ^ Albert, A.; et al. (Antares Collaboration, IceCube Collaboration, Pierre Auger Collaboration, LIGO Scientific Collaboration, & Virgo Collaboration) (October 2017). "Search for high-energy neutrinos from binary neutron star merger GW 170817 with ANTARES, IceCube, and the Pierre Auger Observatory" (PDF). 850 (2): L35. arXiv:1710.05839. Bibcode:2017ApJ...850L..35A. doi:10.3847/2041-8213/aa9aed.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help)CS1 maint: unflagged free DOI (link) - ^ Bravo, Sylvia (16 October 2016). "No neutrino emission from a binary neutron star merger". IceCube South Pole Neutrino Observatory. Retrieved 20 October 2017.

- ^ Sokol, Joshua (25 August 2017). "What happens when two neutron stars collide? Scientific revolution". Wired. Retrieved 27 August 2017.

- ^ a b c d Abbott, B. P.; et al. (2017). "Gravitational waves and gamma-rays from a binary neutron star merger: GW 170817 and GRB 170817A". The Astrophysical Journal Letters. 848 (2): L13. arXiv:1710.05834. Bibcode:2017ApJ...848L..13A. doi:10.3847/2041-8213/aa920c.

- ^ a b Berger, Edo (16 October 2017). LIGO/Virgo Press Conference. Event occurs at 1h48m. Retrieved 29 October 2017.

- ^ Margalit, Ben; Metzger, Brian D. (21 November 2017). "Constraining the Maximum Mass of Neutron Stars from Multi-messenger Observations of GW 170817". The Astrophysical Journal Letters. 850 (2): L19. arXiv:1710.05938. Bibcode:2017ApJ...850L..19M. doi:10.3847/2041-8213/aa991c.

- ^ van Putten, Maurice H P M; Della Valle, Massimo (January 2019). "Observational evidence for extended emission to GW 170817". Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society: Letters. 482 (1): L46 – L49. arXiv:1806.02165. Bibcode:2019MNRAS.482L..46V. doi:10.1093/mnrasl/sly166.

we report on a possible detection of extended emission (EE) in gravitational radiation during GRB170817A: a descending chirp with characteristic time-scale τs = 3.01±0.2 s in a (H1,L1)-spectrogram up to 700 Hz with Gaussian equivalent level of confidence greater than 3.3 σ based on causality alone following edge detection applied to (H1,L1)-spectrograms merged by frequency coincidences. Additional confidence derives from the strength of this EE. The observed frequencies below 1 kHz indicate a hypermassive magnetar rather than a black hole, spinning down by magnetic winds and interactions with dynamical mass ejecta.

- ^ "First identification of a heavy element born from neutron star collision - Newly created strontium, an element used in fireworks, detected in space for the first time following observations with ESO telescope". www.eso.org. Retrieved 27 October 2019.

- ^ "ArXiv.org search for GW 170817". Retrieved 18 October 2017.

- ^ DNews (7 August 2013). "Kilonova Alert! Hubble Solves Gamma Ray Burst Mystery". Seeker.

- ^ a b Schmidt, Fabian (18 December 2017). "Viewpoint: Reining in Alternative Gravity". Physics. 10. doi:10.1103/physics.10.134.

- ^ Kitching, Thomas (13 December 2017). "How crashing neutron stars killed off some of our best ideas about what 'dark energy' is". The Conversation – via phys.org.

- ^ Lombriser, Lucas; Taylor, Andy (28 September 2015). "Breaking a Dark Degeneracy with Gravitational Waves". Journal of Cosmology and Astroparticle Physics. 2016 (3): 031. arXiv:1509.08458. Bibcode:2016JCAP...03..031L. doi:10.1088/1475-7516/2016/03/031.

- ^ Lombriser, Lucas; Lima, Nelson (2017). "Challenges to self-acceleration in modified gravity from gravitational waves and large-scale structure". Phys. Lett. B. 765: 382–385. arXiv:1602.07670. Bibcode:2017PhLB..765..382L. doi:10.1016/j.physletb.2016.12.048.

- ^ Bettoni, Dario; Ezquiaga, Jose María; Hinterbichler, Kurt; Zumalacárregui, Miguel (14 April 2017). "Speed of gravitational waves and the fate of Scalar-Tensor Gravity". Physical Review D. 95 (8): 084029. arXiv:1608.01982. Bibcode:2017PhRvD..95h4029B. doi:10.1103/PhysRevD.95.084029. ISSN 2470-0010.

- ^ Creminelli, Paolo; Vernizzi, Filippo (16 October 2017). "Dark Energy after GW 170817". Phys. Rev. Lett. 119 (25): 251302. arXiv:1710.05877. Bibcode:2017PhRvL.119y1302C. doi:10.1103/PhysRevLett.119.251302. PMID 29303308.

- ^ Ezquiaga, Jose María; Zumalacárregui, Miguel (18 December 2017). "Dark energy after GW 170817: Dead ends and the road ahead". Physical Review Letters. 119 (25): 251304. arXiv:1710.05901. Bibcode:2017PhRvL.119y1304E. doi:10.1103/PhysRevLett.119.251304. PMID 29303304.

- ^ "Quest to settle riddle over Einstein's theory may soon be over". phys.org. 10 February 2017. Retrieved 29 October 2017.

- ^ "Theoretical battle: Dark energy vs. modified gravity". Ars Technica. 25 February 2017. Retrieved 27 October 2017.

- ^ "Gravitational waves". Science News. Retrieved 1 November 2017.

- ^ Creminelli, Paolo; Vernizzi, Filippo (16 October 2017). "Dark Energy after GW 170817". Phys. Rev. Lett. 119 (25): 251302. arXiv:1710.05877. Bibcode:2017PhRvL.119y1302C. doi:10.1103/PhysRevLett.119.251302. PMID 29303308.

- ^ Sakstein, Jeremy; Jain, Bhuvnesh (16 October 2017). "Implications of the neutron star merger GW 170817 for cosmological Scalar-Tensor Theories". Phys. Rev. Lett. 119 (25): 251303. arXiv:1710.05893. Bibcode:2017PhRvL.119y1303S. doi:10.1103/PhysRevLett.119.251303. PMID 29303345.

- ^ Ezquiaga, Jose María; Zumalacárregui, Miguel (16 October 2017). "Dark energy after GW 170817: Dead ends and the road ahead". Phys. Rev. Lett. 119 (25): 251304. arXiv:1710.05901. Bibcode:2017PhRvL.119y1304E. doi:10.1103/PhysRevLett.119.251304. PMID 29303304.

- ^ Boran, Sibel; Desai, Shantanu; Kahya, Emre; Woodard, Richard (2018). "GW 170817 falsifies dark matter emulators". Phys. Rev. D. 97 (4): 041501. arXiv:1710.06168. Bibcode:2018PhRvD..97d1501B. doi:10.1103/PhysRevD.97.041501.

- ^ Baker, T.; Bellini, E.; Ferreira, P.G.; Lagos, M.; Noller, J.; Sawicki, I. (19 October 2017). "Strong constraints on cosmological gravity from GW 170817 and GRB 170817A". Phys. Rev. Lett. 119 (25): 251301. arXiv:1710.06394. Bibcode:2017PhRvL.119y1301B. doi:10.1103/PhysRevLett.119.251301. PMID 29303333.

- ^ a b Loeb, Abraham; 1M2H Collaboration; Dark Energy Camera GW-EM Collaboration the DES Collaboration; DLT40 Collaboration; Las Cumbres Observatory Collaboration; VINROUGE Collaboration; MASTER Collaboration (2017). "A gravitational-wave standard siren measurement of the Hubble constant". Nature. 551 (7678): 85–88. arXiv:1710.05835. Bibcode:2017Natur.551...85A. doi:10.1038/nature24471. ISSN 0028-0836. PMID 29094696.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) - ^ Scharping, Nathaniel (18 October 2017). "Gravitational waves show how fast the Universe is expanding". Astronomy. Retrieved 18 October 2017.

- ^ Hotokezaka, K.; et al. (8 July 2019). "A Hubble constant measurement from superluminal motion of the jet in GW 170817". Nature Astronomy: 385. arXiv:1806.10596. Bibcode:2019NatAs.tmp..385H. doi:10.1038/s41550-019-0820-1. Retrieved 8 July 2019.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: bibcode (link) - ^ "New method may resolve difficulty in measuring universe's expansion – Neutron star mergers can provide new 'cosmic ruler'". National Radio Astronomy Observatory. 8 July 2019. Retrieved 8 July 2019 – via EurekAlert!.

- ^ Finley, Dave (8 July 2019). "New method may resolve difficulty in measuring Universe's expansion". National Radio Astronomy Observatory. Retrieved 8 July 2019.

- ^ Lerner, Louise (22 October 2018). "Gravitational waves could soon provide measure of universe's expansion". Retrieved 22 October 2018 – via Phys.org.

- ^ Chen, Hsin-Yu; Fishbach, Maya; Holz, Daniel E. (17 October 2018). "A two per cent Hubble constant measurement from standard sirens within five years". Nature. 562 (7728): 545–547. arXiv:1712.06531. Bibcode:2018Natur.562..545C. doi:10.1038/s41586-018-0606-0. PMID 30333628.

- ^ Ghosh, Pallab (26 March 2018). "Stephen Hawking's final interview: A beautiful Universe". BBC news. Retrieved 26 March 2018.

- ^ Rueda, J.A.; et al. (28 September 2018). "GRB 170817A-GW 170817-AT 2017gfo and the observations of NS-NS, NS-WD, and WD-WD mergers". Journal of Cosmology and Astroparticle Physics. 2018 (10): 006. arXiv:1802.10027. Bibcode:2018JCAP...10..006R. doi:10.1088/1475-7516/2018/10/006.

- ^ Watson, Darach; Hansen, Camilla J.; Selsing, Jonatan; Koch, Andreas; Malesani, Daniele B.; Andersen, Anja C.; Fynbo, Johan P. U.; Arcones, Almudena; Bauswein, Andreas; Covino, Stefano; Grado, Aniello (October 2019). "Identification of strontium in the merger of two neutron stars". Nature. 574 (7779): 497–500. arXiv:1910.10510. Bibcode:2019Natur.574..497W. doi:10.1038/s41586-019-1676-3. ISSN 1476-4687. PMID 31645733.

External links

- "Detections". LIGO.

- "Follow-up observations of GW 170817".

- Related videos (16 October 2017):