Annexation of Tibet by the People's Republic of China

| Annexation of Tibet by the People's Republic of China | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the Cold War | |||||||

| |||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

|

|

| ||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

|

|

| ||||||

| Units involved | |||||||

| Tibetan Army[3] | People's Liberation Army[4][5] | ||||||

| History of Tibet |

|---|

|

| See also |

|

|

The annexation of Tibet by the People's Republic of China (called the "Peaceful Liberation of Tibet" by the Chinese government[6][7][8] and the "Chinese invasion of Tibet" by the Tibetan Government in Exile[9][10]) was the process by which the People's Republic of China (PRC) gained control of Tibet. These regions came under the control of China after attempts by the Government of Tibet to gain international recognition, efforts to modernize its military, negotiations between the Government of Tibet and the PRC, a military conflict in the Chamdo area of western Kham in October 1950, and the eventual acceptance of the Seventeen Point Agreement by the Government of Tibet under Chinese pressure in October 1951.[11][12] In some Western opinions, the incorporation of Tibet into China is viewed as an annexation.[13][14] The Government of Tibet and Tibetan social structure remained in place in the Tibetan polity under the authority of China until the 1959 Tibetan uprising, when the Dalai Lama fled into exile and after which the Government of Tibet and Tibetan social structures were dissolved.[15]

Background

Tibet came under the rule of the Qing dynasty of China in 1720 after Chinese forces successfully expelled the forces of the Dzungar Khanate.[16] Tibet would remain under Qing rule until 1912.[17] The succeeding Republic of China claimed inheritance of all territories held by the Qing dynasty, including Tibet.[18] This claim was provided for in the Imperial Edict of the Abdication of the Qing Emperor (清帝退位詔書) signed by the Empress Dowager Longyu on behalf of the five-year-old Xuantong Emperor: "[...] the continued territorial integrity of the lands of the five races, Manchu, Han, Mongol, Hui, and Tibetan into one great Republic of China" ([...] 仍合滿、漢、蒙、回、藏五族完全領土,為一大中華民國).[19][20][21] The Provisional Constitution of the Republic of China adopted in 1912 specifically established frontier regions of the new republic, including Tibet, as integral parts of the state.[22]

In 1913, shortly after the British invasion of Tibet in 1904, the creation of the position of British Trade Agent at Gyantse and the Xinhai Revolution in 1911, most of the area comprising the present-day Tibet Autonomous Region (TAR) (Ü-Tsang and western Kham) became a de facto autonomous or independent polity, independent from the rest of the Republic of China[23][24] under a British protectorate,[citation needed] with the rest of the present day TAR coming under Tibetan Government rule by 1917.[25] Some border areas with high ethnic Tibetan populations (Amdo and Eastern Kham) remained under Chinese Nationalist Party (Kuomintang) or local warlord control.[26]

The TAR region is also known as "Political Tibet", while all areas with a high ethnic Tibetan population are collectively known as "Ethnic Tibet". Political Tibet refers to the polity ruled continuously by Tibetan governments since earliest times until 1951, whereas ethnic Tibet refers to regions north and east where Tibetans historically predominated but where, down to modern times, Tibetan jurisdiction was irregular and limited to just certain areas.[27]

At the time Political Tibet obtained de facto independence, its socio-economic and political systems resembled Medieval Europe.[28] Attempts by the 13th Dalai Lama between 1913 and 1933 to enlarge and modernize the Tibetan military had eventually failed, largely due to opposition from powerful aristocrats and monks.[29][30] The Tibetan government had little contact with other governments of the world during its period of de facto independence,[30] with some exceptions; notably India, the United Kingdom, and the United States.[31][32] This left Tibet diplomatically isolated and cut off to the point where it could not make its positions on the issues well known to the international community[33] and it was restricted by treaties that gave the British Empire authority over taxes, foreign relations and fortifications.

Government of Tibet's attempts to remain independent

In July 1949, in order to prevent Chinese Communist Party-sponsored agitation in political Tibet, the Tibetan government expelled the (Nationalist) Chinese delegation in Lhasa.[34] In November 1949, it sent a letter to the U.S. State Department and a copy to Mao Zedong, and a separate letter to the UK, declaring its intent to defend itself "by all possible means" against PRC troop incursions into Tibet.[35]

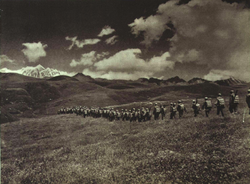

In the preceding three decades, the conservative Tibetan government had consciously de-emphasized its military and refrained from modernizing.[36] Hasty attempts at modernization and enlarging the military began in 1949,[37] but proved mostly unsuccessful on both counts.[38] It was too late to raise and train an effective army.[why?][39] India provided some small arms aid and military training,[40] however the People's Liberation Army was much larger, better trained, better led, better equipped, and more experienced than the Tibetan Army.[41][42][43]

In 1950, the 14th Dalai Lama was 15 years old and had not attained his majority, so Regent Taktra was the acting head of the Tibetan Government.[44] The period of the Dalai Lama’s minority is traditionally one of instability and division, and the division and instability were made more intense by the recent Reting conspiracy[45] and a 1947 regency dispute.[32]

Preparations by the People's Republic of China

Both the PRC and their predecessors the Kuomintang (ROC) had always maintained that Tibet was a part of China.[43] The PRC also proclaimed an ideological motivation to liberate the Tibetans from a theocratic feudal system.[46] In September 1949, shortly before the proclamation of the People’s Republic of China, the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) made it a top priority to incorporate Tibet, Taiwan, Hainan Island, and the Pescadores Islands into the PRC,[47][48] peacefully or by force.[49] Because Tibet was unlikely to voluntarily give up its de facto independence, Mao in December 1949 ordered that preparations be made to march into Tibet at Qamdo (Chamdo), in order to induce the Tibetan Government to negotiate.[49] The PRC had over a million men under arms[49] and had extensive combat experience from the recently concluded Chinese Civil War.

Negotiations between the Government of Tibet and the PRC prior to hostilities

Talks between Tibet and China were mediated with the governments of Britain and India.

On 7 March 1950, a Tibetan delegation arrived in Kalimpong, India to open a dialogue with the newly declared PRC and to secure assurances that the PRC would respect Tibetan "territorial integrity", among other things. The onset of talks was delayed by debate between the Tibetan delegation, India, Britain, and the PRC about the location of the talks. Tibet favored Singapore or Hong Kong (not Beijing; at the time romanized as Peking); Britain favored India (not Hong Kong or Singapore); and India and the PRC favored Beijing; but India and Britain preferred no talks at all.[citation needed] The Tibetan delegation did eventually meet with the PRC’s ambassador General Yuan Zhongxian in Delhi on 16 September 1950. Yuan communicated a 3-point proposal that Tibet be regarded as part of China, that China be responsible for Tibet’s defense, and that China be responsible for Tibet’s trade and foreign relations. Acceptance would lead to peaceful Chinese sovereignty, or otherwise war. The Tibetans undertook to maintain the relationship between China and Tibet as one of priest-patron:

"Tibet will remain independent as it is at present, and we will continue to have very close 'priest-patron' relations with China. Also, there is no need to liberate Tibet from imperialism, since there are no British, American or Guomindang imperialists in Tibet, and Tibet is ruled and protected by the Dalai Lama (not any foreign power)" – Tsepon W. D. Shakabpa[50]: 46

They and their head delegate Tsepon W. D. Shakabpa, on 19 September, recommended cooperation, with some stipulations about implementation. Chinese troops need not be stationed in Tibet, it was argued, since it was under no threat, and if attacked by India or Nepal could appeal to China for military assistance. While Lhasa deliberated, on 7 October 1950, Chinese troops advanced into eastern Tibet, crossing the border at 5 places.[51] The purpose was not to invade Tibet per se but to capture the Tibetan army in Chamdo, demoralize the Lhasa government, and thus exert powerful pressure to send negotiators to Beijing to sign terms for a handover of Tibet.[52] On 21 October, Lhasa instructed its delegation to leave immediately for Beijing for consultations with the Communist government, and to accept the first provision, if the status of the Dalai Lama could be guaranteed, while rejecting the other two conditions. It later rescinded even acceptance of the first demand, after a divination before the Six-Armed Mahākāla deities indicated that the three points could not be accepted, since Tibet would fall under foreign domination.[53][54][55]

Invasion of Chamdo

After months of failed negotiations,[56] attempts by Tibet to secure foreign support and assistance,[57] PRC and Tibetan troop buildups, the People's Liberation Army (PLA) crossed the Jinsha River on 6 or 7 October 1950.[58][59] Two PLA units quickly surrounded the outnumbered Tibetan forces and captured the border town of Chamdo by 19 October, by which time 114 PLA[60] soldiers and 180 Tibetan[60][61][62] soldiers had been killed or wounded. Writing in 1962, Zhang Guohua claimed "over 5,700 enemy men were destroyed" and "more than 3,000" peacefully surrendered.[63] Active hostilities were limited to a border area northeast of the Gyamo Ngul Chu River and east of the 96th meridian.[64] After capturing Chamdo, the PLA broke off hostilities,[61][65] sent a captured commander, Ngabo, to Lhasa to reiterate terms of negotiation, and waited for Tibetan representatives to respond through delegates to Beijing.[66]

Further negotiations and incorporation

The PLA sent released prisoners (among them Ngapoi Ngawang Jigme, a captured governor) to Lhasa to negotiate with the Dalai Lama on the PLA's behalf. Chinese broadcasts promised that if Tibet was "peacefully liberated", the Tibetan elites could keep their positions and power.[67]

El Salvador sponsored a complaint by the Tibetan government at the UN, but India and the United Kingdom prevented it from being debated.[68]

Tibetan negotiators were sent to Beijing and presented with an already-finished document commonly referred to as the Seventeen Point Agreement. There was no negotiation offered by the Chinese delegation; although the PRC stated it would allow Tibet to reform at its own pace and in its own way, keep internal affairs self-governing and allow religious freedom; it would also have to agree to be part of China. The Tibetan negotiators were not allowed to communicate with their government on this key point, and pressured into signing the agreement on 23 May 1951, despite never having been given permission to sign anything in the name of the government. This was the first time in Tibetan history its government had accepted – albeit unwillingly – China's position on the two nations' shared history.[69] Tibetan representatives in Beijing and the PRC Government signed the Seventeen Point Agreement on 23 May 1951, authorizing the PLA presence and Central People's Government rule in Political Tibet.[70] The terms of the agreement had not been cleared with the Tibetan Government before signing and the Tibetan Government was divided about whether it was better to accept the document as written or to flee into exile. The Dalai Lama, who by this time had ascended to the throne, chose not to flee into exile, and formally accepted the 17 Point Agreement in October 1951.[71] According to Tibetan sources, on 24 October, on behalf of the Dalai Lama, general Zhang Jingwu sent a telegram to Mao Zedong with confirmation of the support of the Agreement, and there is evidence that Ngapoi Ngawang Jigme simply came to Zhang and said that the Tibetan Government agreed to send a telegram on 24 October, instead of the formal Dalai Lama's approval.[72] Shortly afterwards, the PLA entered Lhasa.[73] The subsequent incorporation of Tibet is officially known in the People's Republic of China as the "Peaceful Liberation of Tibet" (Chinese: 和平解放西藏地方 Hépíng jiěfàng xīzàng dìfāng), as promoted by the state media.[74]

Aftermath

For several years the Tibetan Government remained in place in the areas of Tibet where it had ruled prior to the outbreak of hostilities, except for the area surrounding Qamdo that was occupied by the PLA in 1950, which was placed under the authority of the Qamdo Liberation Committee and outside the Tibetan Government's control.[76] During this time, areas under the Tibetan Government maintained a large degree of autonomy from the Central Government and were generally allowed to maintain their traditional social structure.[77]

In 1956, Tibetan militias in the ethnically Tibetan region of eastern Kham just outside the Tibet Autonomous Region, spurred by PRC government experiments in land reform, started fighting against the government.[78] The militias united to form Chushi Gangdruk Volunteer Force. When the fighting spread to Lhasa in 1959, the Dalai Lama fled Tibet. Both he and the PRC government in Tibet subsequently repudiated the 17 Point Agreement and the PRC government in Tibet dissolved the Tibetan Local Government.[15]

The legacy of this action continues decades later. Jamling Tenzing Norgay, the son of Tibetan born Tenzing Norgay who was one of the first two individuals known to summit Mount Everest, said in his book, "I felt fortunate to have been born on the south side of the Himalaya, safe from the Chinese invasion of Tibet."[79]

See also

- History of Tibet

- Tibet under Yuan rule

- Tibet under Qing rule

- Tibet (1912–1951)

- History of Tibet (1950–present)

- 1959 Tibetan uprising

- Tibetan sovereignty debate

- Monument to the Peaceful Liberation of Tibet

- Sino-Tibetan War (1930–1932)

- Incorporation of Xinjiang into the People's Republic of China

- List of military occupations

References

Citations

- ^ Mackerras, Colin. Yorke, Amanda. The Cambridge Handbook of Contemporary China. [1991]. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-521-38755-8. p.100.

- ^ Goldstein, Melvyn C. (1991). A history of modern Tibet, 1913-1951, the demise of the lamaist state. University of California Press. p. 639.

- ^ Freedom in Exile: The Autobiography of the Dalai Lama, 14th Dalai Lama, London: Little, Brown and Co, 1990 ISBN 0-349-10462-X

- ^ Laird 2006 p.301.

- ^ Shakya 1999, p.43

- ^ "Peaceful Liberation of Tibet". Xinhua News Agency. Archived from the original on 16 June 2017. Retrieved 16 August 2017.

- ^ Dawa Norbu (2001). China's Tibet Policy. Psychology Press. pp. 300–301. ISBN 978-0-7007-0474-3.

- ^ Melvyn C. Goldstein; Gelek Rimpoche (1989). A History of Modern Tibet, 1913-1951: The Demise of the Lamaist State. University of California Press. pp. 679, 740. ISBN 978-0-520-06140-8.

- ^ "China could not succeed in destroying Buddhism in Tibet: Sangay". Central Tibetan Administration. 25 May 2017. Archived from the original on 21 September 2018. Retrieved 16 August 2017.

- ^ Siling, Luo (14 August 2016). "A Writer's Quest to Unearth the Roots of Tibet's Unrest". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on 27 November 2018. Retrieved 15 February 2020.

- ^ Anne-Marie Blondeau; Katia Buffetrille (2008). Authenticating Tibet: Answers to China's 100 Questions. University of California Press. p. 61. ISBN 978-0-520-24464-1. Archived from the original on 23 June 2016. Retrieved 15 November 2015.

It was evident that the Chinese were not prepared to accept any compromises and that the Tibetans were compelled, under the threat of immediate armed invasion, to sign the Chinese proposal.

- ^ Tsepon Wangchuk Deden Shakabpa (October 2009). One Hundred Thousand Moons: An Advanced Political History of Tibet. BRILL. pp. 953, 955. ISBN 978-90-04-17732-1.

- ^ Matthew Wills (23 May 2016). "Tibet and China 65 Years Later: Tibet was annexed by the Chinese 65 years ago. The struggle for Tibetan independence has continued ever since". JSTOR Daily. Archived from the original on 1 July 2019. Retrieved 1 July 2019.

- ^ "Tibet Through Chinese Eyes", The Atlantic, 1999, archived from the original on 19 May 2017, retrieved 11 September 2017,

In Western opinion, the "Tibet question" is settled: Tibet should not be part of China; before being forcibly annexed, in 1951, it was an independent country.

- ^ a b Goldstein 1997 p.54,55. Feigon 1996 p.160,161. Shakya 1999 p.208,240,241. (all sources: fled Tibet, repudiated agreement, dissolved local government).

- ^ Lin, Hsiao-ting (2011). Tibet and Nationalist China's Frontier: Intrigues and Ethnopolitics, 1928-49. pp. 7–8. ISBN 9780774859882.

- ^ Lin (2011). p. 9.

- ^ Tanner, Harold (2009). China: A History. p. 419. ISBN 978-0872209152.

- ^ Esherick, Joseph; Kayali, Hasan; Van Young, Eric (2006). Empire to Nation: Historical Perspectives on the Making of the Modern World. p. 245. ISBN 9780742578159.

- ^ Zhai, Zhiyong (2017). 憲法何以中國. p. 190. ISBN 9789629373214.

- ^ Gao, Quanxi (2016). 政治憲法與未來憲制. p. 273. ISBN 9789629372910.

- ^ Zhao, Suisheng (2004). A Nation-state by Construction: Dynamics of Modern Chinese Nationalism. p. 68. ISBN 9780804750011.

- ^ Shakya 1999 p.4

- ^ Melvin C. Goldstein, A History of Modern Tibet, vol. I : 1913-1951, The Demise of the Lamaist State, University of California Press, 1989, p. 815: "Tibet unquestionably controlled its own internal and external affairs during the period from 1913 to 1951 and repeatedly attempted to secure recognition and validation of its de facto autonomy/independence."

- ^ Feigon 1996 p.119

- ^ Shakya 1999 p.6,27. Feigon 1996 p.28

- ^ The classic distinction drawn by Sir Charles Bell and Hugh Richardson. See Melvin C. Goldstein, 'Change, Conflict and Continuity among a community of Nomadic Pastoralists: A Case Study from Western Tibet, 1950-1990,' in Robert Barnett and Shirin Akiner, (eds.,) Resistance and Reform in Tibet, Indiana University Press, Bloomington, 1994, pp. 76-90, pp.77-8.

- ^ Shakya 1999 p.11

- ^ Feigon 1996 p.119-122. Goldstein 1997 p.34,35.

- ^ a b Shakya 1999 p.5,11

- ^ Shakya 1999 p.7,15,16

- ^ a b Goldstein 1997 p.37

- ^ Goldstein 1997 p.36

- ^ Shakya 1999 p.5,7,8

- ^ Shakya 1999 p.20. Goldstein 1997 p.42

- ^ Melvin C. Goldstein,A History of Modern Tibet:The Calm Before the Storm: 1951-1955, University of California Press, 2009, Vol.2, p.51.

- ^ Shakya 1999 p.12

- ^ Shakya 1999 p.20,21. Goldstein 1997 p.37,41-43

- ^ Goldstein, 209 pp.51-2.

- ^ Shakya 1999 p.26

- ^ Shakya 1999 p.12 (Tibetan army poorly trained and equipped).

- ^ Goldstein 1997 p.41 (armed and led), p.45 (led and organized).

- ^ a b Feigon 1996 p.142 (trained).

- ^ Shakya 1999 p.5

- ^ Shakya 1999 p.4,5

- ^ Dawa Norbu, China's Tibet policy,Routledge, 2001, p.195

- ^ Goldstein 1997 p.41.

- ^ Shakya 1999 p.3.

- ^ a b c Goldstein 1997 p.44

- ^ Goldstein, Melvyn C (2009). A History of Modern Tibet. Volume 2: The Calm Before the Storm, 1951-1955. Goldstein, Melvyn C. Berkeley, California: University of California Press. ISBN 9780520249417. OCLC 76167591.

- ^ Melvin C. Goldstein, A History of Modern Tibet: The Calm Before the Storm: 1951-1955, University of California Press, 2009, Vol.2, p.48.

- ^ Melvin C. Goldstein, A History of Modern Tibet, vol.2, p.48-9.

- ^ Shakya 1999 p.27-32 (entire paragraph).

- ^ W. D. Shakabpa,One hundred thousand moons, BRILL, 2010 trans. Derek F. Maher, Vol.1, pp.916-917, and ch.20 pp.928-942, esp.pp.928-33.

- ^ Melvin C. Goldstein, A History of Modern Tibet: The Calm Before the Storm: 1951-1955, Vol.2, ibid.pp.41-57.

- ^ Shakya 1999 p.28-32

- ^ Shakya 1999 p.12,20,21

- ^ Feigon 1996 p.142. Shakya 1999 p.37.

- ^ Shakya 1999 p.32 (6 Oct). Goldstein 1997 p.45 (7 Oct).

- ^ a b Jiawei Wang et Nima Gyaincain, The historical Status of China's Tibet Archived 29 April 2016 at the Wayback Machine, China Intercontinental Press, 1997, p. 209 (see also The Local Government of Tibet Refused Peace Talks and the PLA Was Forced to Fight the Qamdo Battle Archived 18 March 2012 at the Wayback Machine, china.com.cn): "The Quamdo battle thus came to a victorious end on October 24, with 114 PLA soldiers and 180 Tibetan troops killed or wounded."

- ^ a b Shakya 1999, pg. 45.

- ^ Feigon 1996, p.144.

- ^ Survey of China Mainland Press, no. 2854 p.5,6

- ^ Shakya 1999 map p.xiv

- ^ Goldstein 1997 p.45

- ^ Shakya 1999 p.49

- ^ Laird, 2006 p.306.

- ^ Tibet: The Lost Frontier, Claude Arpi, Lancer Publishers, October 2008, ISBN 0-9815378-4-7

- ^ 'The political and religious institutions of Tibet would remain unchanged, and any social and economic reforms would be undertaken only by the Tibetans themselves at their own pace.' Thomas Laird, The Story of Tibet: Conversations with the Dalai Lama,Grove Press, 2007, p.307.

- ^ Goldstein 1997 p.47

- ^ Goldstein 1997 p.48 (had not been cleared) p.48,49 (government was divided), p.49 (chose not to flee), p.52 (accepted agreement).

- ^ Kuzmin, S.L. Hidden Tibet: History of Independence and Occupation. Dharamsala, LTWA, 2011, p. 190 - Archived 30 October 2012 at the Wayback Machine ISBN 978-93-80359-47-2

- ^ Goldstein 1997 p.51

- ^ Yang Fan (10 April 2018). "西藏和平解放65周年:细数那些翻天覆地的变化" [The 65th anniversary of the peaceful liberation of Tibet: Counting those earth-shaking changes]. 中国军网. Archived from the original on 9 February 2019. Retrieved 2 February 2019.

- ^ Goldstein, Melvyn C. (1 August 2007). A History of Modern Tibet, volume 2: The Calm before the Storm: 1951-1955. University of California Press. p. 227. ISBN 978-0-520-93332-3.

Chinese and Tibetan government officials at a banquet celebrating the "peaceful liberation" of Tibet.

- ^ Shakya 1999 p.96,97,128.

- ^ Goldstein 1997 p.52-54. Feigon 1996 p.148,149,151

- ^ Goldstein 1997 p.53

- ^ Norgay, Jamling Tenzing (2002). Touching My Father's Soul: A Sherpa's Journey to the Top of Everest. San Francisco, California: HarperSanFrancisco. p. 4. ISBN 0062516876. OCLC 943113647.

Sources

- Feigon, Lee. Demystifying Tibet: Unlocking the Secrets of the Land of Snows (1996) Ivan R. Dee Inc. ISBN 1-56663-089-4

- Ford, Robert. Wind Between The Worlds The extraordinary first-person account of a Westerner's life in Tibet as an official of the Dalai Lama (1957) David Mckay Co., Inc.

- Goldstein, Melvyn C. A History of Modern Tibet, 1913-1951: The Demise of the Lamaist State (1989) University of California Press. ISBN 978-0-520-06140-8

- Goldstein, Melvyn C. The Snow Lion and the Dragon: China, Tibet, and the Dalai Lama (1997) University of California Press. ISBN 0-520-21254-1

- Grunfeld, A. Tom. The Making of Modern Tibet (1996) East Gate Book. ISBN 978-1-56324-713-2

- Knaus, Robert Kenneth. Orphans of the Cold War: America and the Tibetan Struggle for Survival (1999) PublicAffairs . ISBN 978-1-891620-18-8

- Laird, Thomas. The Story of Tibet: Conversations with the Dalai Lama (2006) Grove Press. ISBN 0-8021-1827-5

- Shakya, Tsering. The Dragon in the Land of Snows (1999) Columbia University Press. ISBN 0-231-11814-7

- Robert W. Ford Captured in Tibet, Oxford University Press, 1990, ISBN 978-0-19-581570-2

Further reading

The Tibet issue: Tibetan view, BBC, The Tibet issue: China's view, BBC