Abolitionism

| Part of a series on |

| Forced labour and slavery |

|---|

|

Abolitionism is a movement to end slavery, whether formal or informal. In Western Europe and the Americas, abolitionism is a historical movement to end the African and Indian slave trade and set slaves free. King Charles I of Spain, usually known as Emperor Charles V, following the example of the Swedish monarch, passed a law which would have abolished colonial slavery in 1542, although this law was not passed in the largest colonial states, and so was not enforced. In the late 17th century, the Roman Catholic Church, taking up a plea by Lourenco da Silva de Mendouca, officially condemned the slave trade, which was affirmed vehemently by Pope Gregory XVI in 1839. An abolitionist movement only started in the late 18th century, however, when English and American Quakers began to question the morality of slavery. James Oglethorpe was among the first to articulate the Enlightenment case against slavery, banning it in the Province of Georgia on humanist grounds, arguing against it in Parliament, and eventually encouraging his friends Granville Sharp and Hannah More to vigorously pursue the cause. Soon after his death in 1785, they joined with William Wilberforce and others in forming the Clapham Sect.[1] The Somersett Case in 1772, which emancipated a slave in England, helped launch the British movement to abolish slavery. Though anti-slavery sentiments were widespread by the late 18th century, the colonies and emerging nations that used slave labour continued to do so: French, English and Portuguese territories in the West Indies; South America; and the Southern United States.

After the American Revolution established the United States, northern states, beginning with Pennsylvania in 1780, passed legislation during the next two decades abolishing slavery, sometimes by gradual emancipation. Massachusetts ratified a constitution that declared all men equal; freedom suits challenging slavery based on this principle brought an end to slavery in the state. Vermont, which existed as an unrecognized state from 1777 to 1791, abolished adult slavery in 1777. In other states, such as Virginia, similar declarations of rights were interpreted by the courts as not applicable to Africans. During the following decades, the abolitionist movement grew in northern states, and Congress regulated the expansion of slavery in new states admitted to the union. David Brion Davis argues that the main driving force was a new moral consciousness, with an intellectual assist from the Enlightenment, and a powerful impulse from religious Quakers and evangelicals.[2]

France abolished slavery within the French Kingdom in 1315. Revolutionary France abolished slavery in its colonies in 1794, before it was restored by Napoleon in 1802. Haiti achieved independence from France in 1804 and brought an end to slavery in its territory, establishing the second republic in the New World. The northern states in the U.S. all abolished slavery by 1804. The United Kingdom and the United States outlawed the international slave trade in 1807, after which Britain led efforts to block slave ships. Britain abolished slavery throughout the British Empire with the Slavery Abolition Act 1833, the French colonies abolished it in 1848 and the U.S. in 1865 with the 13th Amendment to the U.S. Constitution.

In Eastern Europe, groups organized to abolish the enslavement of the Roma in Wallachia and Moldavia; and to emancipate the serfs in Russia (Emancipation reform of 1861). It was declared illegal in 1948 under the Universal Declaration of Human Rights. The last country to abolish legal slavery was Mauritania, where it was officially abolished by presidential decree in 1981.[3] Today, child and adult slavery and forced labour are illegal in most countries, as well as being against international law, but a high rate of human trafficking for labor and for sexual bondage continues to affect tens of millions of adults and children.

France

Abolition in continental France (1315)

In 1315, Louis X, king of France, published a decree proclaiming that "France signifies freedom" and that any slave setting foot on the French ground should be freed. This prompted subsequent governments to circumscribe slavery in the overseas colonies.[4]

Some cases of African slaves freed by setting foot on the French soil were recorded such as this example of a Norman slave merchant who tried to sell slaves in Bordeaux in 1571. He was arrested and his slaves were freed according to a declaration of the Parlement of Guyenne which stated that slavery was intolerable in France.[5] Born into slavery in Saint Domingue, Thomas-Alexandre Dumas became free when his father brought him to France in 1776.

Code Noir and Age of Enlightenment

As in other New World colonies, the French relied on the Atlantic slave trade for labour for their sugar cane plantations in their Caribbean colonies; the French West Indies. In addition, French colonists in Louisiane in North America held slaves, particularly in the South around New Orleans, where they established sugar-cane plantations. Over time in all these areas, a class of free people of colour (Gens de couleur libres) developed, many of whom became educated, property owners and sometimes slave owners.

Louis XIV's Code Noir regulated the slave trade and institution in the colonies. It gave unparalleled rights to slaves. It includes the right to marry, to gather publicly or to take Sundays off. Although the Code Noir authorized and codified cruel corporal punishment against slaves under certain conditions, it forbade slave owners to torture them or to separate families. It also forced the owners to instruct them in the Catholic faith, implying that Africans were human beings endowed with a soul, a fact that was not seen as evident until then. It resulted in a far higher percentage of blacks being free in 1830 (13.2% in Louisiana compared to 0.8% in Mississippi.[6]) They were on average exceptionally literate, with a significant number of them owning businesses, properties and even slaves.[7][8] While some other free people of colour, such as Julien Raimond, spoke against slavery.

The Code Noir also forbade interracial marriages, but it was often ignored in French colonial society and the mulattoes became an intermediate caste between whites and blacks, while in the English colonies mulattoes and blacks were considered equal and discriminated against equally.[8][9]

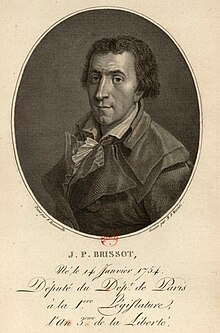

During the Age of Enlightenment, many philosophers wrote pamphlets against slavery and its moral and economical justifications, including Montesquieu in The Spirit of the Laws (1748) or in the Encyclopédie. In 1788, Jacques Pierre Brissot founded the Society of the Friends of the Blacks (Société des Amis des Noirs) to work for abolition of slavery.

After the Revolution, on 4 April 1792, France granted free people of colour full citizenship.

The revolt of slaves in the largest Caribbean French colony of Saint-Domingue in 1791 was the beginning of what became the Haitian Revolution led by Toussaint L'Ouverture. Rebellion swept through the north of the island, and many whites and free people of colour were killed, as well as slaves. Slavery was first abolished in 1793 in St. Domingue by Sonthonax, a French Commissioner sent by the Convention in order to safeguard the allegiance of the population to revolutionary France.

First general abolition of slavery (1794)

The Convention, the first elected Assembly of the First Republic (1792–1804), on 4 February 1794, under the leadership of Maximilien Robespierre, abolished slavery in law in France and its colonies. Abbé Grégoire and the Society of the Friends of the Blacks were part of the abolitionist movement, which had laid important groundwork in building anti-slavery sentiment in the metropole. The first article of the law stated that "Slavery was abolished" in the French colonies, while the second article stated that "slave-owners would be indemnified" with financial compensation for the value of their slaves. The French constitution passed in 1795 included in the declaration of the Rights of Man that slavery was abolished.

Re-establishment of slavery in the colonies (1802)

During the French Revolutionary Wars, French slave-owners massively joined the counter-revolution and, through the Whitehall Accord, they threatened to move the French Caribbean colonies under British control, as Great Britain still allowed slavery. Fearing secession from these islands, successfully lobbied by planters and concerned about revenues from the West Indies, and influenced by the slaveholder family of his wife,Napoleon Bonaparte decided to re-establish slavery after becoming First Consul. He promulgated the law of 20 May 1802 and sent military governors and troops to the colonies to impose it. On 10 May 1802, Colonel Delgrès launched a rebellion in Guadeloupe against Napoleon's representative, General Richepanse. The rebellion was repressed, and slavery was re-established. The news of this event sparked another wave of rebellion in Saint-Domingue. Although from 1802, Napoleon sent more than 20,000 troops to the island, two-thirds died mostly due to yellow fever. He withdrew the remaining 7,000 troops and slaves achieved an independent republic they called Haïti in 1804. Seeing the failure of the Saint-Domingue expedition, in 1803 Napoleon decided to sell the Louisiana Territory to the United States. The French governments initially refused to recognise Haiti. It forced the nation to pay a substantial amount of reparations (which it could ill afford) for losses during the revolution and did not recognise its government until 1825.

Second abolition (1848) and subsequent events

On 27 April 1848, under the Second Republic (1848–52), the decree-law of Schœlcher abolished slavery in the remaining colonies. The state bought the slaves from the colons (white colonists; Békés in Creole), and then freed them.

At about the same time, France started colonising Africa and gained possession of much of West Africa by 1900. In 1905, the French abolished slavery in most of French West Africa. The French also attempted to abolish Tuareg slavery following the Kaocen Revolt. In the region of the Sahel, slavery has however long persisted.

Passed on 10 May 2001, the Taubira law officially acknowledges slavery and the Atlantic Slave Trade as a crime against humanity. 10 May was chosen as the day dedicated to recognition of the crime of slavery.

Great Britain

The last known form of enforced servitude of adults (villeinage) had disappeared in England by the beginning of the 17th century. In a 1569 court case involving Cartwright, who had bought a slave from Russia, the court ruled that English law could not recognize slavery, as it was never established officially. This ruling was overshadowed by later developments. It was upheld in 1700 by the Lord Chief Justice John Holt when he ruled that a slave became free as soon as he arrived in England.[10]

In addition to English colonists importing slaves to the North American colonies, by the 18th century, traders began to import slaves from Africa, India and East Asia (where they were trading) to London and Edinburgh to work as personal servants. Men who migrated to the North American colonies often took their East Indian slaves or servants with them, as East Indians have been documented in colonial records.[11][12]

Some of the first freedom suits, court cases in the British Isles to challenge the legality of slavery, took place in Scotland in 1755 and 1769. The cases were Montgomery v. Sheddan (1755) and Spens v. Dalrymple (1769). Each of the slaves had been baptized in Scotland and challenged the legality of slavery. They set the precedent of legal procedure in British courts that would later lead to successful outcomes for the plaintiffs. In these cases, deaths of the plaintiff and defendant, respectively, brought an end before court decisions.[13]

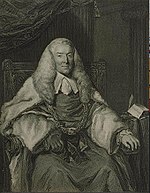

African slaves were not bought or sold in London but were brought by masters from other areas. Together with people from other nations, especially non-Christian, Africans were considered foreigners, not able to be English subjects. At the time, England had no naturalization procedure. The African slaves' legal status was unclear until 1772 and Somersett's Case, when the fugitive slave James Somersett forced a decision by the courts. Somersett had escaped, and his master, Charles Steuart, had him captured and imprisoned on board a ship, intending to ship him to Jamaica to be resold into slavery. While in London, Somersett had been baptized; three godparents issued a writ of habeas corpus. As a result, Lord Mansfield, Chief Justice of the Court of the King's Bench, had to judge whether Somersett's abduction was lawful or not under English Common Law. No legislation had ever been passed to establish slavery in England. The case received national attention, and five advocates supported the action on behalf of Somersett.

In his judgment of 22 June 1772, Mansfield declared:

The state of slavery is of such a nature that it is incapable of being introduced on any reasons, moral or political, but only by positive law, which preserves its force long after the reasons, occasions, and time itself from whence it was created, is erased from memory. It is so odious, that nothing can be suffered to support it, but positive law. Whatever inconveniences, therefore, may follow from a decision, I cannot say this case is allowed or approved by the law of England; and therefore the black must be discharged.[14]

Although the exact legal implications of the judgement are unclear when analysed by lawyers, the judgement was generally taken at the time to have determined that slavery did not exist under English common law and was thus prohibited in England.[15] The decision did not apply to the British overseas territories; by then, for example, the American colonies had established slavery by positive laws.[16] Somersett's case became a significant part of the common law of slavery in the English-speaking world and it helped launch the movement to abolish slavery.[17]

After reading about Somersett's Case, Joseph Knight, an enslaved African who had been purchased by his master John Wedderburn in Jamaica and brought to Scotland, left him. Married and with a child, he filed a freedom suit, on the grounds that he could not be held as a slave in Great Britain. In the case of Knight v. Wedderburn (1778), Wedderburn said that Knight owed him "perpetual servitude". The Court of Sessions of Scotland ruled against him, saying that chattel slavery was not recognized under the law of Scotland, and slaves could seek court protection to leave a master or avoid being forcibly removed from Scotland to be returned to slavery in the colonies.[13]

But at the same time, legally mandated, hereditary slavery of Scots persons in Scotland had existed from 1606[18] and continued until 1799, when colliers and salters were emancipated by an act of the Parliament of Great Britain (39 Geo.III. c. 56). Skilled workers, they were restricted to a place and could be sold with the works. A prior law enacted in 1775 (15 Geo.III. c. 28) was intended to end what the act referred to as "a state of slavery and bondage,"[19] but that was ineffective, necessitating the 1799 act.

British Empire

In 1783, an anti-slavery movement began among the British public to end slavery throughout the British Empire. In 1785, the English poet William Cowper wrote:

We have no slaves at home – Then why abroad? Slaves cannot breathe in England; if their lungs receive our air, that moment they are free. They touch our country, and their shackles fall. That's noble, and bespeaks a nation proud. And jealous of the blessing. Spread it then, And let it circulate through every vein.[20]

After the formation of the Committee for the Abolition of the Slave Trade in 1787, William Wilberforce led the cause of abolition through the parliamentary campaign. Thomas Clarkson became the group's most prominent researcher, gathering vast amounts of data on the trade. One aspect of abolitionism during this period was the effective use of images such as the famous Josiah Wedgwood "Am I Not A Man And A Brother?" anti-slavery medallion of 1787, which Clarkson described as "promoting the cause of justice, humanity and freedom".[21][22] The Slave Trade Act was passed by the British Parliament on 25 March 1807, making the slave trade illegal throughout the British Empire.[23] Britain used its influence to coerce other countries to agree treaties to end their slave trade and allow the Royal Navy to seize their slave ships.[24][25]

In the 1820s, the abolitionist movement revived to campaign against the institution of slavery itself. In 1823 the first Anti-Slavery Society was founded. Many of its members had previously campaigned against the slave trade. On August 28, 1833, the Slavery Abolition Act was given Royal Assent, which paved the way for the abolition of slavery throughout the British Empire, which was substantially achieved in 1838. In 1839, the British and Foreign Anti-Slavery Society was formed by Joseph Sturge, which attempted to outlaw slavery worldwide and also to pressure the government to help enforce the suppression of the slave trade by declaring slave traders pirates. The world's oldest international human rights organization, it continues today as Anti-Slavery International.[26]

Moldavia and Wallachia

In the principalities of Wallachia and Moldavia (both now part of Romania), the government held slavery of the Roma (often referred to as Gypsies) as legal at the beginning of the 19th century. The progressive pro-European and anti-Ottoman movement, which gradually gained power in the two principalities, also worked to abolish that slavery. Between 1843 and 1855, the principalities emancipated all of the 250,000 enslaved Roma people.[27]

In the Americas

Bartolomé de las Casas was a 16th-century Spanish Dominican priest, the first resident Bishop of Chiapas. As a settler in the New World he witnessed and opposed the poor treatment of the Native Americans by the Spanish colonists. He advocated before King Charles V, Holy Roman Emperor on behalf of rights for the natives. Originally supporting the importation of African slaves as labourers, he eventually changed and became an advocate for the Africans in the colonies.[28][29] His book, A Short Account of the Destruction of the Indies, contributed to Spanish passage of colonial legislation known as the New Laws of 1542, which abolished native slavery for the first time in European colonial history. It ultimately led to the Valladolid debate.

Latin America

During the early 19th century, slavery expanded rapidly in Brazil, Cuba, and the United States, while at the same time the new republics of mainland Spanish America became committed to the gradual abolition of slavery. During the Independence Wars (1810–1826), slavery was abolished in most of Latin America. Slavery continued until 1873 in Puerto Rico, 1886 in Cuba, and 1888 in Brazil by the Lei Áurea or "Golden Law." Chile declared freedom of wombs in 1811, followed by the United Provinces of the River Plate in 1813, but without abolishing slavery completely. While Chile abolished slavery in 1823, Argentina did so with the signing of the Argentine Constitution of 1853. Colombia abolished slavery in 1852. Slavery was abolished in Uruguay during the Guerra Grande, by both the government of Fructuoso Rivera and the government in exile of Manuel Oribe.[30]

Canada

While many blacks who arrived in Nova Scotia during the American Revolution were free, others were not.[32] Black slaves also arrived in Nova Scotia as the property of White American Loyalists. In 1772, prior to the American Revolution, Britain outlawed the slave trade in the British Isles followed by the Knight v. Wedderburn decision in Scotland in 1778. This decision, in turn, influenced the colony of Nova Scotia. In 1788, abolitionist James Drummond MacGregor from Pictou published the first anti-slavery literature in Canada and began purchasing slaves' freedom and chastising his colleagues in the Presbyterian church who owned slaves.[33] In 1790 John Burbidge freed his slaves. Led by Richard John Uniacke, in 1787, 1789 and again on 11 January 1808, the Nova Scotian legislature refused to legalize slavery.[34][35] Two chief justices, Thomas Andrew Lumisden Strange (1790–1796) and Sampson Salter Blowers (1797–1832) were instrumental in freeing slaves from their owners in Nova Scotia.[36][37][38] They were held in high regard in the colony. By the end of the War of 1812 and the arrival of the Black Refugees, there were few slaves left in Nova Scotia.[39] (The Slave Trade Act outlawed the slave trade in the British Empire in 1807 and the Slavery Abolition Act of 1833 outlawed slavery all together.)

With slaves escaping to New York and New England, legislation for gradual emancipation was passed in Upper Canada (1793) and Lower Canada (1803). In Upper Canada the Assembly ruled that no slaves could be imported; slaves already in the province would remain enslaved until death, no new slaves could be brought into Upper Canada, and children born to female slaves would be slaves but must be freed at the age of 25. In practice, some slavery continued until abolished in the entire British Empire in the 1830s.[40]

United States

The historian James M. McPherson defines an abolitionist "as one who before the Civil War had agitated for the immediate, unconditional, and total abolition of slavery in the United States." He does not include antislavery activists such as Abraham Lincoln or the Republican Party, which called for the gradual ending of slavery.[41]

The first attempts to end slavery in the British/American colonies came from Thomas Jefferson and some of his contemporaries. Despite the fact that Jefferson was a lifelong slaveholder, he included strong anti-slavery language in the original draft of the Declaration of Independence, but other delegates took it out.[42] Benjamin Franklin, also a slaveholder for most of his life, was a leading member of the Pennsylvania Society for the Abolition of Slavery, the first recognized organization for abolitionists in the United States.[43] Following the Revolutionary War, Northern states abolished slavery, beginning with the 1777 constitution of Vermont, followed by Pennsylvania's gradual emancipation act in 1780. Other states with more of an economic interest in slaves, such as New York and New Jersey, also passed gradual emancipation laws, but by 1804, all the northern states had abolished it. Some slaves continued in servitude for two more decades but most were freed.

Also in the postwar years, individual slaveholders, particularly in the Upper South, manumitted slaves, sometimes in their wills. Many noted they had been moved by the revolutionary ideals of the equality of men. The number of free blacks as a proportion of the black population increased from less than one percent to nearly ten percent from 1790 to 1810 in the Upper South as a result of these actions.

As President, on 2 March 1807, Jefferson signed the Act Prohibiting Importation of Slaves and it took effect in 1808, which was the earliest allowed under the Constitution. In 1820 he privately supported the Missouri Compromise, believing it would help to end slavery.[42][44] He left the anti-slavery struggle to younger men after that.[45]

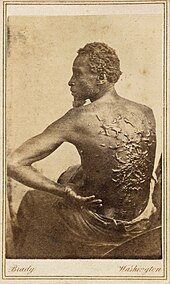

In the 1850s in the fifteen states constituting the American South, slavery was established legally. While it was fading away in the cities and border states, it remained strong in plantation areas that grew cotton for export, or sugar, tobacco or hemp. By the 1860 United States Census, the slave population in the United States had grown to four million.[46] American abolitionism was based in the North, and white Southerners alleged it fostered slave rebellion.

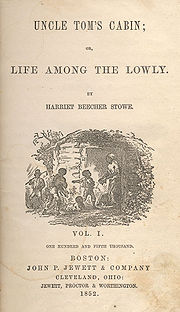

The white abolitionist movement in the North was led by social reformers, especially William Lloyd Garrison, founder of the American Anti-Slavery Society; writers such as John Greenleaf Whittier and Harriet Beecher Stowe. Black activists included former slaves such as Frederick Douglass; and free blacks such as the brothers Charles Henry Langston and John Mercer Langston, who helped found the Ohio Anti-Slavery Society.[47] Some abolitionists said that slavery was criminal and a sin; they also criticized slave owners of using black women as concubines and taking sexual advantage of them.[48]

The Republican Party wanted to achieve the gradual extinction of slavery by market forces, for its members believed that free labour was superior to slave labour. Southern leaders said the Republican policy of blocking the expansion of slavery into the West made them second-class citizens, and challenged their autonomy. With the 1860 presidential victory of Abraham Lincoln, seven Deep South states whose economy was based on cotton and slavery decided to secede and form a new nation. The American Civil War broke out in April 1861 with the firing on Fort Sumter in South Carolina. When Lincoln called for troops to suppress the rebellion, four more slave states seceded.

Civil War and final emancipation

Lincoln's Emancipation Proclamation was an executive order of the U.S. government issued on 1 January 1863, changing the legal status of 3 million slaves in designated areas of the Confederacy from "slave" to "free". Slaves were legally freed by the Proclamation and became actually free by escaping to federal lines, or by advances of federal troops. Many served the federal army as teamsters, cooks, laundresses and labourers. Plantation owners, realizing that emancipation would destroy their economic system, sometimes moved their slaves as far as possible out of reach of the Union army.[49] By "Juneteenth" (19 June 1865, in Texas), the Union Army controlled all of the Confederacy and liberated all its slaves. The owners were never compensated.[50][51]

The border states were exempt from the Emancipation Proclamation, but they too (except Delaware) began their own emancipation programs.[52] When the Union Army entered Confederate areas, thousands of slaves escaped to freedom behind Union Army lines, and in 1863 many men started serving as the United States Colored Troops. The 13th Amendment to the U.S. Constitution took effect in December 1865 and finally ended slavery throughout the United States. It also abolished slavery among the Indian tribes, including the Alaska tribes that became part of the U.S. in 1867.[53]

Notable abolitionists

White opponents of slavery and Blacks, who played a considerable role in the movement, including some escaped slaves, traditionally were called abolitionists.

- Toussaint Louverture

- Abbé Grégoire

- Harriet Tubman

- John Brown

- Harriet Beecher Stowe

- Johns Hopkins

- John D. Rockefeller

- William Lloyd Garrison

- Frederick Douglass

- Henry David Thoreau

- Oren Burbank Cheney

- John Woolman

Abolitionist publications

United States

- The Emancipator (1819–20): founded in 1819 by Elihu Embree as the Manumission Intelligencier, The Emancipator ceased publication in October 1820 due to Embree's illness. It was sold in 1821 and became The Genius of Universal Emancipation.

- Genius of Universal Emancipation (1821–39): an abolitionist newspaper published and edited by Benjamin Lundy. In 1829 it employed William Lloyd Garrison, who would go on to form 'The Liberator.

- The Liberator (1831–65): a weekly newspaper founded by William Lloyd Garrison.

- The Slave's Friend (1836–38): an anti-slavery magazine for children produced by the American Anti-Slavery Society (AASS).

- The Philanthropist (1836–37): newspaper published in Ohio for and owned by the Anti-Slavery Society.

- The Liberty Bell, by Friends of Freedom (1839–58): an annual gift book edited and published by Maria Weston Chapman, to be sold or gifted to participants in the National Anti-Slavery Bazaar organized by the Boston Female Anti-Slavery Society.

- National Anti-Slavery Standard (1840–70): the official weekly newspaper of the American Anti-Slavery Society, the paper published continuously until the ratification of the Fifteenth Amendment to the United States Constitution in 1870.

- The Unconstitutionality of Slavery (1845): a pamphlet by Lysander Spooner advocating the view that the U.S. Constitution prohibited slavery.

- The National Era (1847–60): a weekly newspaper which featured the works of John Greenleaf Whittier, who served as associate editor, and first published, as a serial, Harriet Beecher Stowe's Uncle Tom's Cabin (1851).

- North Star (1847–51): an anti-slavery American newspaper published by the escaped slave, author, and abolitionist, Frederick Douglass.

International

- Slave narratives, books published in the U.S. and elsewhere by former slaves or about former slaves, relating their experiences.

- Anti-Slavery International publications

Notable opponents of slavery

National abolition dates

Commemoration

The abolitionist movements and the abolition of slavery have been commemorated in different ways around the world in modern times. The United Nations General Assembly declared 2004 the International Year to Commemorate the Struggle against Slavery and its Abolition. This proclamation marked the bicentenary of the birth of the first black state, Haiti. Numerous exhibitions, events and research programmes were connected to the initiative.

2007 witnessed major exhibitions in British museums and galleries to mark the anniversary of the 1807 abolition act – 1807 Commemorated[54] 2008 marks the 201st anniversary of the Abolition of the Slave Trade in the British Empire.[55] It also marks the 175th anniversary of the abolition of Slavery in the British Empire.[56]

The Faculty of Law at the University of Ottawa held a major international conference entitled, "Routes to Freedom: Reflections on the Bicentenary of the Abolition of the Slave Trade", from 14 to 16 March 2008.[57] Actor and human rights activist Danny Glover delivered the keynote speech announcing the creation of two major scholarships intended for University of Ottawa law students specializing in international law and social justice at the conference's gala dinner.

Brooklyn, New York, has begun work on commemorating the abolitionist movement in New York.

Contemporary abolitionism

On 10 December 1948, the General Assembly of the United Nations adopted the Universal Declaration of Human Rights. Article 4 states:

No one shall be held in slavery or servitude; slavery and the slave trade shall be prohibited in all their forms.

Although outlawed in most countries, slavery is nonetheless practised secretly in many parts of the world. Enslavement still takes place in the United States, Europe, and Latin America,[58] as well as parts of Africa, the Middle East, and South Asia.[59] There are an estimated 27 million victims of slavery worldwide.[60] In Mauritania alone, estimates are that up to 600,000 men, women and children, or 20% of the population, are enslaved. Many of them are used as bonded labour.[61]

Modern-day abolitionists have emerged over the last several years, as awareness of slavery around the world has grown, with groups such as Anti-Slavery International, the American Anti-Slavery Group, International Justice Mission, and Free the Slaves working to rid the world of slavery.

In the United States, The Action Group to End Human Trafficking and Modern-Day Slavery is a coalition of NGOs, foundations and corporations working to develop a policy agenda for abolishing slavery and human trafficking. Since 1997, the United States Department of Justice has, through work with the Coalition of Immokalee Workers, prosecuted six individuals in Florida on charges of slavery in the agricultural industry. These prosecutions have led to freedom for over 1000 enslaved workers in the tomato and orange fields of South Florida. This is only one example of the contemporary fight against slavery worldwide. Slavery exists most widely in agricultural labor, apparel and sex industries, and service jobs in some regions.

In 2000, the United States passed the Victims of Trafficking and Violence Protection Act (TVPA) "to combat trafficking in persons, especially into the sex trade, slavery, and involuntary servitude."[62] The TVPA also "created new law enforcement tools to strengthen the prosecution and punishment of traffickers, making human trafficking a Federal crime with severe penalties."[63]

In 2014, for the first time in history major Anglican, Catholic, and Orthodox Christian leaders, as well as Jewish, Muslim, Hindu, and Buddhist leaders, met to sign a shared commitment against modern-day slavery; the declaration they signed calls for the elimination of slavery and human trafficking by the year 2020.[64] The signatories were: Pope Francis, Her Holiness Mātā Amṛtānandamayī (also known as Amma), Venerable Bhikkhuni Thich Nu Chân Không (representing Zen Master Thích Nhất Hạnh), The Most Ven. Datuk K Sri Dhammaratana, Chief High Priest of Malaysia, Rabbi Dr. Abraham Skorka, Rabbi Dr. David Rosen, Dr. Abbas Abdalla Abbas Soliman, Undersecretary of State of Al Azhar Alsharif (representing Mohamed Ahmed El-Tayeb, Grand Imam of Al-Azhar), Grand Ayatollah Mohammad Taqi al-Modarresi, Sheikh Naziyah Razzaq Jaafar, Special advisor of Grand Ayatollah (representing Grand Ayatollah Sheikh Basheer Hussain al Najafi), Sheikh Omar Abboud, Most Revd and Right Hon Justin Welby, Archbishop of Canterbury, and His Eminence Metropolitan Emmanuel of France (representing His All-Holiness Ecumenical Patriarch Bartholomew.)[64]

The United States Department of State publishes the annual Trafficking in Persons Report, identifying countries as either Tier 1, Tier 2, Tier 2 Watch List or Tier 3, depending upon three factors: "(1) The extent to which the country is a country of origin, transit, or destination for severe forms of trafficking; (2) The extent to which the government of the country does not comply with the TVPA's minimum standards including, in particular, the extent of the government's trafficking-related corruption; and (3) The resources and capabilities of the government to address and eliminate severe forms of trafficking in persons."[65]

See also

- Abolition of slavery timeline

- Anti-Slavery International

- Anti-Slavery Society

- Compensated emancipation

- International Day for the Abolition of Slavery

- List of Abolitionist Forerunners (Thomas Clarkson)

- Monument to the abolition of slavery

- Slavery in the British and French Caribbean

- The Slave in European Art

- Slavery in Vermont

References

- ^ Wilson, Thomas, The Oglethorpe Plan, 201–206.

- ^ David Brion Davis, The Problem of Slavery in the Age of Revolution, 1770–1823 (1975).

- ^ "Slavery's last stronghold", CNN. March 2012.

- ^ Christopher L. Miller, The French Atlantic Triangle: literature and culture of the slave trade, Duke University Press, p. 20.

- ^ Malick W. Ghachem, The Old Regime and the Haitian Revolution, Cambridge University Press, p. 54.

- ^ Rodney Stark, For the Glory of God: How Monotheism Led to Reformations, Science, Witch-hunts, and the End of Slavery, Princeton University Press, 2003, 0p. 322. Note that there was typo in the original hardcover stating "31.2 percent"; this was corrected to 13.2% in the paperback edition and can be verified using 1830 census data.

- ^ Samantha Cook, Sarah Hull (2011). The Rough Guide to the USA. Rough Guides UK.

- ^ a b Terry L. Jones, (2007). The Louisiana Journey. Gibbs Smith.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: extra punctuation (link) - ^ Martin H. Steinberg, Disorders of Hemoglobin: Genetics, Pathophysiology, and Clinical Management, pp. 725–726.

- ^ V. C. D. Mtubani, "African Slaves and English Law", PULA Botswana Journal of African Studies, Vol. 3, No. 2, November 1983. Retrieved 24 February 2011.

- ^ Paul Heinegg, Free African Americans of Virginia, North Carolina, South Carolina, Maryland and Delaware, 1999–2005, "WEAVER FAMILY: Three members of the Weaver family, probably brothers, were called 'East Indians' in Lancaster County, [VA] [court records] between 1707 and 1711." "'The indenture of Indians (Native Americans) as servants was not common in Maryland ... the indenture of East Indian servants was more common." Retrieved 15 February 2008.

- ^ Francis C. Assisi, "First Indian-American Identified: Mary Fisher, Born 1680 in Maryland", IndoLink, Quote: "Documents available from American archival sources of the colonial period now confirm the presence of indentured servants or slaves who were brought from the Indian subcontinent, via England, to work for their European American masters." Retrieved 20 April 2010.

- ^ a b "Slavery, freedom or perpetual servitude? – the Joseph Knight case". National Archives of Scotland. Retrieved 27 November 2010.

- ^ Frederick Charles Moncrieff, The Wit and Wisdom of the Bench and Bar, The Lawbook Exchange, 2006, pp. 85–86.

- ^ Mowat, Robert Balmain, History of the English-Speaking Peoples, Oxford University Press, 1943, p. 162.

- ^ MacEwen, Martin, Housing, Race and Law: The British Experience, Routledge, 2002, p. 39.

- ^ Peter P. Hinks, John R. McKivigan, R. Owen Williams, Encyclopedia of Antislavery and Abolition, Greenwood Publishing Group, 2007, p. 643.

- ^ Brown, K. M.; et al., eds. (2007). "Regarding colliers and salters (ref: 1605/6/39)". The Records of the Parliaments of Scotland to 1707. St. Andrews: University of St. Andrews.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: postscript (link) - ^ May, Thomas Erskine (1895). "Last Relics of Slavery". The Constitutional History of England (1760–1860). Vol. II. New York: A. C. Armstrong and Son. pp. 274–275.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: postscript (link) - ^ Rhodes, Nick (2003). William Cowper: Selected Poems, Routledge, 2003, p. 84.

- ^ "Wedgwood". Retrieved 12 August 2015.

Thomas Clarkson wrote of the medallion; promoting the cause of justice, humanity and freedom.

- ^ Elizabeth Mcgrath and Jean Michel Massing (eds), The Slave in European Art: From Renaissance Trophy to Abolitionist Emblem, London, 2012.

- ^ Clarkson, T., History of the Rise, Progress and Accomplishment of the Abolition of the African Slave Trade by the British Parliament, London, 1808.

- ^ Falola, Toyin; Warnock, Amanda (2007). Encyclopedia of the middle passage. Greenwood Press. pp. xxi, xxxiii–xxxiv. ISBN 9780313334801.

- ^ "The legal and diplomatic background to the seizure of foreign vessels by the Royal Navy".

- ^ Anti-Slavery International UNESCO. Retrieved 11 October 2011.

- ^ Viorel Achim (2010). "Romanian Abolitionists on the Future of the Emancipated Gypsies", Transylvanian Review, Vol. XIX, Supplement no. 4, 2010, p. 23.

- ^ "Columbus 'sparked a genocide'". BBC News. 12 October 2003. Retrieved 21 October 2006.

- ^ Blackburn 1997: 136; Friede 1971:165–166. Las Casas' change in his views on African slavery is expressed particularly in chapters 102 and 129, Book III of his Historia.

- ^ Peter Hinks and John McKivigan, eds. Abolition and Antislavery: A Historical Encyclopedia of the American Mosaic (2015).

- ^ The portrait is now at the National Gallery of Scotland. According to Thomas Akins, this portrait hung in the legislature of Province House (Nova Scotia) in 1847 (see History of Halifax, p. 189).

- ^ "Slavery in the Maritime Provinces". archive.org.

- ^ "Biography – MacGREGOR, JAMES DRUMMOND – Volume VI (1821-1835) – Dictionary of Canadian Biography". biographi.ca.

- ^ Bridglal Pachai & Henry Bishop. Historic Black Nova Scotia, 2006, p. 8.

- ^ John Grant. Black Refugees, p. 31.

- ^ Biography at the Dictionary of Canadian Biography Online

- ^ "Celebrating the 250th Anniversary of the Supreme Court of Nova Scotia". courts.ns.ca.

- ^ Barry Cahill, "Slavery and the Judges of Loyalist Nova Scotia", UNB Law Journal, 43 (1994), pp. 73–135.

- ^ "Nova Scotia Archives - African Nova Scotians". novascotia.ca.

- ^ Robin Winks, Blacks in Canada: A History (1971).

- ^ James M. McPherson (1995). The Abolitionist Legacy: From Reconstruction to the Naacp. Princeton University Press. p. 4.

- ^ a b Monticello Foundation, 2012

- ^ Seymour Stanton Black. Benjamin Franklin: Genius of Kites, Flights, and Voting Rights.

- ^ Peterson, 1960 p. 189.

- ^ Cogliano 2006, p. 219.

- ^ Introduction – Social Aspects of the Civil War, National Park Service.

- ^ Leon F. Litwack and August Meier, eds., "John Mercer Langston: Principle and Politics", in Black Leaders of the 19th century, University of Illinois Press, 1991, pp. 106–111

- ^ James A. Morone (2004). Hellfire Nation: The Politics Of Sin In American History. Yale University Press. p. 154.

- ^ Leon F. Litwack, Been in the Storm So Long: The Aftermath of Slavery (1979), pp. 30–36, 105–66.

- ^ Michael Vorenberg, ed., The Emancipation Proclamation: A Brief History with Documents (2010).

- ^ Peter Kolchin, "Reexamining Southern Emancipation in Comparative Perspective," Journal of Southern History, 81#1 (February 2015), 7–40.

- ^ Foner, Eric; Garraty, John A. "EMANCIPATION PROCLAMATION". History Channel. Retrieved 13 October 2014.

- ^ Vorenberg, Final Freedom: The Civil War, the Abolition of Slavery, and the Thirteenth Amendment (2004).

- ^ "1807 Commemorated". Institute for the Public Understanding of the Past and the Institute of Historical Research. 2007. Retrieved 27 November 2010.

- ^ "Slave Trade Act 1807 UK". anti-slaverysociety.addr.com.

- ^ "Slavery Abolition Act 1833 UK". anti-slaverysociety.addr.com.

- ^ "Les Chemins de la Liberté : Réflexions à l'occasion du bicentenaire de l'abolition de l'esclavage / Routes to Freedom : Reflections on the Bicentenary of the Abolition of the Slave Trade". University of Ottawa, Canada. Retrieved 27 November 2010.

- ^ Bales, Kevin. Ending Slavery: How We Free Today's Slaves. University of California Press, 2007, ISBN 978-0-520-25470-1.

- ^ "Does Slavery Still Exist?" Anti-Slavery Society.

- ^ "Slavery in the Twenty-First Century". UN Chronicle. Issue 3. 2005.

{{cite journal}}:|volume=has extra text (help) - ^ "Mauritanian MPs pass slavery law". BBC News. BBC. 9 August 2007.

- ^ Public Law 106–386 – 28 October 2000, Victims of Trafficking and Violence Protection Act of 2000.

- ^ US Department of Health and Human Services, TVPA Fact Sheet.

- ^ a b "Pope Francis And Other Religious Leaders Sign Declaration Against Modern Slavery". The Huffington Post.

- ^ "US Department of State Trafficking in Persons Report 2008, Introduction". state.gov.

Further reading

- Bader-Zaar, Birgitta, "Abolitionism in the Atlantic World: The Organization and Interaction of Anti-Slavery Movements in the Eighteenth and Nineteenth Centuries", European History Online, Mainz: Institute of European History, 2010; retrieved 14 June 2012.

- Blackwell, Marilyn S. "'Women Were Among Our Primeval Abolitionists': Women and Organized Antislavery in Vermont, 1834–1848," Vermont History, 82 (Winter-Spring 2014), 13–44.

- Carey, Brycchan, and Geoffrey Plank, eds. Quakers and Abolition (University of Illinois Press, 2014), 264 pp.

- Coupland, Sir Reginald. "The British Anti-Slavery Movement." London : F. Cass, 1964.

- Davis, David Brion, The Problem of Slavery in the Age of Revolution, 1770–1823 (1999); The Problem of Slavery in Western Culture (1988)

- Drescher, Seymour. Abolition: A History of Slavery and Antislavery (2009)

- Finkelman, Paul, ed. Encyclopedia of Slavery (1999)

- Gordon, M. Slavery in the Arab World (1989)

- Gould, Philip. Barbaric Traffic: Commerce and Antislavery in the 18th-century Atlantic World (2003)

- Hellie, Richard. Slavery in Russia: 1450–1725 (1982)

- Hinks, Peter, and John McKivigan, eds. Encyclopedia of Antislavery and Abolition (2 vol. 2006) ISBN 0-313-33142-1; 846pp; 300 articles by experts

- Kolchin, Peter. Unfree Labor; American Slavery and Russian Serfdom (1987)

- Kolchin, Peter. "Reexamining Southern Emancipation in Comparative Perspective," Journal of Southern History, (Feb. 2015) 81#1 pp: 7–40.

- Palen, Marc-William. "Free-Trade Ideology and Transatlantic Abolitionism: A Historiography." Journal of the History of Economic Thought 37 (June 2015): 291-304.

- Rodriguez, Junius P., ed. "Encyclopedia of Emancipation and Abolition in the Transatlantic World" (2007)

- Rodriguez, Junius P., ed. The Historical Encyclopedia of World Slavery (1997)

- Sinha, Manisha. The Slave's Cause: A History of Abolition (Yale UP, 2016) 784pp; Highly detailed coverage of the American movement

- Thomas, Hugh. The Slave Trade: The Story of the Atlantic Slave Trade: 1440–1870 (2006)

External links

- Mémoire St Barth | History of St Barthélemy (archives & history of slavery, slave trade and their abolition), Comité de Liaison et d'Application des Sources Historiques.

- Largest Surviving Anti Slave Trade Petition from Manchester, UK 1806

- Original Document Proposing Abolition of Slavery 13th Amendment

- "John Brown's body and blood" by Ari Kelman: a review in the TLS, 14 February 2007.

- "Scotland and the Abolition of the Slave Trade" – schools resource

- Report of the Brown University Steering Committee on Slavery and Justice

- Twentieth Century Solutions of the Abolition of Slavery

- Elijah Parish Lovejoy: A Martyr on the Altar of American Liberty

- Brycchan Carey's pages listing British abolitionists

- Teaching resources about Slavery and Abolition on blackhistory4schools.com

- "The Abolition of the Slave Trade", The National Archives (UK)

- Towards Liberty: Slavery, the Slave Trade, Abolition and Emancipation. Produced by Sheffield City Council's Libraries and Archives (UK)

- The slavery debate

- John Brown Museum

- American Abolitionism

- American Abolitionists, comprehensive list of abolitionists and anti-slavery activists and organizations in the United States

- History of the British abolitionist movement by Right Honourable Lord Archer of Sandwell

- "Slavery – The emancipation movement in Britain", lecture by James Walvin at Gresham College, 5 March 2007 (available for video and audio download)

- Underground Railroad: Escape from Slavery. Scholastic.com

- "Black Canada and the Journey to Freedom"

- 1807 Commemorated

- The Action Group

- Trafficking in Persons Report 2008, US Department of State

- National Underground Railroad Freedom Center in Cincinnati, Ohio

- The Liberator Files, Horace Seldon's collection and summary of research of William Lloyd Garrison's The Liberator original copies at the Boston Public Library, Boston, Massachusetts.

- University of Detroit Mercy Black Abolitionist Archive, a collection of more than 800 speeches by antebellum blacks and approximately 1,000 editorials from the period.

- Abolitionist movement

- Raymond James Krohn, "Abolitionist Movement", Encyclopedia of Civil Liberties in the United States