Angiotensin II receptor blocker

Angiotensin II receptor antagonists, also known as angiotensin receptor blockers (ARBs), AT1-receptor antagonists or sartans, are a group of pharmaceuticals that modulate the renin-angiotensin-aldosterone system. Their main uses are in the treatment of hypertension (high blood pressure), diabetic nephropathy (kidney damage due to diabetes) and congestive heart failure.

Medical uses

A 2011 meta analysis on 37 trials (on hypertension, heart failure and nephropathy) found that angiotensin receptor blockers had no effect on the outcome of myocardial infarction, angina pectoris, cardiovascular mortality and total mortality compared to controls (placebo/active treatment), placebo, or active treatment. But they reduced the risk of stroke, heart failure, and new onset diabetes compared with controls, or placebo or with active treatment.[1] After exclusion of two trials that were fraudulent (the Kyoto heart study and the Jikei heart trial both on valsartan Novartis) the results remained unchanged.[2][3]

Hypertension

Angiotensin II receptor antagonists are used for the treatment of hypertension where the patient is intolerant of ACE inhibitor therapy. They are only rarely associated with the persistent dry cough and/or angioedema that limit ACE inhibitor therapy.[4] There are no clinically meaningful BP lowering differences between available ARBs. The BP lowering effect of ARBs is modest and similar to ACE inhibitors as a class; the magnitude of average trough BP lowering for ARBs at maximum recommended doses and above is -8/-5 mmHg. 60 to 70% of the trough BP lowering effect occurs with recommended starting doses.[5] Combined ARB hydrochlorothiazide therapy produced substantially greater reductions in systolic (16.1 to 20.6 mmHg) and diastolic (9.9 to 13.6 mmHg) blood-pressure than ARB monotherapy.[6]

In hypertension there was no mortality reduction with ARB treatment. On the contrary ACE inhibitors clearly reduced mortality.[7]

Heart failure

Angiotensin II receptor blockers are used for the treatment of heart failure in patients intolerant of ACE inhibitor therapy.

In people with symptomatic heart failure and systolic dysfunction or with preserved ejection fraction, ARBs compared to placebo or ACEIs do not reduce total mortality or morbidity. ARBs are better tolerated than ACEIs but do not appear to be as safe and well tolerated as placebo in terms of withdrawals due to adverse effects.[8]

Combination therapy with ARBs and ACE inhibitors reduces admissions for heart failure in patients with congestive heart failure when compared to ACE inhibitor therapy alone, but does not reduce overall mortality or all-cause hospitalization and is associated with more adverse events. The combination therapy had a higher risk of worsening renal function, symptomatic hypotension, a higher rate of permanent discontinuation of trial medications,[9] and a higher risk of hyperkaliemia.[10]

Nephropathy

Since 2003 several guidelines suggested that ACE inhibitors (ACEI) and angiotensin II receptor blockers (ARB) were equivalent and were preferred agents in patients with microalbuminuria due to significant reductions in all-cause mortality, cardiovascular events and progression of chronic kidney disease. Such recommendations were based on existing randomized trials and meta-analyses.[11][12]

A 2011 systematic review of 58 trials in patients with micro- and macroalbuminuria found there was no significant reduction in the risk of all-cause mortality or cardiac–cerebrovascular mortality with ARB versus placebo, ARB versus ACEI or with combined therapy with ACEI + ARB versus monotherapy. There was no reduction in the risk of nonfatal cardiovascular events with ARB versus placebo, contrary to ACEI. The risk of non fatal cardiovascular events was lower with ACEI versus ARB or with combined therapy with ACEI + ARB versus monotherapy. Development of end-stage kidney disease and progression of microalbuminuria to macroalbuminuria were reduced significantly with ARB versus placebo but not with combined therapy with ACEI + ARB versus monotherapy.[12]

Dual blockade

Dual blockade of the renin-angiotensin system include the combination of an ACE inhibitor and an angiotensin-receptor blocker (ARBs), or a direct renin inhibitor (aliskiren Tekturna, Novartis). A meta analysis of 33 randomised controlled trials on dual blockade of the renin-angiotensin system found although it might have seemingly beneficial effects on certain surrogate endpoints as albuminuria and proteinuria, it failed to reduce mortality and was associated with an excessive risk of adverse events such as hyperkalaemia (increased potassium in the blood), hypotension, and renal failure compared with monotherapy. The risk to benefit ratio argues against the use of dual therapy.[10] In 2009 Lancet retracted the 2003 COOPERATE trial of dual renin-angiotensin system inhibition which concluded that combination therapy of an ACE inhibitor and an ARB was superior to an ACE inhibitor alone, and spanked the lead author for serious misconduct.[13][14] By 2008, about 140,000 patients in the U.S. took combined therapy.[15]

On April 4, 2014 EMA recommends against combined use of medicines affecting the renin-angiotensin (RAS) system, and in particular that patients with diabetes-related kidney problems (diabetic nephropathy) should not be given an ARB with an ACE-inhibitor. .[16]

Discovery and development

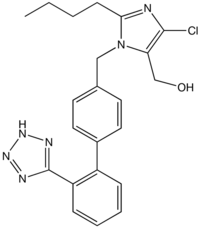

Structure

Losartan, irbesartan, olmesartan, candesartan and valsartan include the tetrazole group (a ring with four nitrogen and one carbon). Losartan, irbesartan, olmesartan, candesartan, and telmisartan include one or two imidazole groups.

Mechanism of action

These substances are AT1-receptor antagonists; that is, they block the activation of angiotensin II AT1 receptors. Blockage of AT1 receptors directly causes vasodilation, reduces secretion of vasopressin, and reduces production and secretion of aldosterone, among other actions. The combined effect reduces blood pressure.

The specific efficacy of each ARB within this class depends upon a combination of three pharmacodynamic and pharmacokinetic parameters. Efficacy requires three key PD/PK areas at an effective level; the parameters of the three characteristics will need to be compiled into a table similar to one below, eliminating duplications and arriving at consensus values; the latter are at variance now.

Pressor inhibition

Pressor inhibition at trough level - this relates to the degree of blockade or inhibition of the blood pressure-raising ("pressor") effect of angiotensin II. However, pressor inhibition is not a measure of blood pressure-lowering (BP) efficacy per se. The rates as listed in the US FDA Package Inserts (PIs) for inhibition of this effect at the 24th hour for the ARBs are as follows: (all doses listed in PI are included)

- Valsartan 80 mg 30%

- Telmisartan 80 mg 40%

- Losartan 100 mg 25–40%

- Irbesartan 150 mg 40%

- Irbesartan 300 mg 60%

- Azilsartan 32 mg 60%

- Olmesartan 20 mg 61%

- Olmesartan 40 mg 74%

AT1 affinity

AT1 affinity vs AT2 is not a meaningful efficacy measurement of BP response. The specific AT1 affinity relates to how specifically attracted the medicine is for the correct receptor, the US FDA PI rates for AT1 affinity are as follows:

- Losartan 1000-fold

- Telmisartan 3000-fold

- Irbesartan 8500-fold

- Azilsartan greater than 10000-fold

- Olmesartan 12500-fold

- Valsartan 20000-fold

Biological half-life

The third area needed to complete the overall efficacy picture of an ARB is its biological half-life. The half-lives from the US FDA PIs are as follows:

- Valsartan 6 hours

- Losartan 6–9 hours

- Azilsartan 11 hours

- Irbesartan 11–15 hours

- Olmesartan 13 hours

- Telmisartan 24 hours

Drug comparison and pharmacokinetics

| Drug | Trade Name | Biological half-life [h] | Protein binding [%] | Bioavailability [%] | Renal/hepatic clearance [%] | Food effect | Daily dosage [mg] |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Losartan | Cozaar | 6-9 h | 98.7% | 33% | 10%/90% | Minimal | 50–100 mg |

| EXP 3174 | 6–9 h | 99.8% | – | 50%/50% | – | – | |

| Candesartan | Atacand | 9h | >99% | 15% | 60%/40% | No | 4–32 mg |

| Valsartan | Diovan | 6 h | 95% | 25% | 30%/70% | No | 80–320 mg |

| Irbesartan | Avapro | 11–15 h | 90–95% | 70% | 1%/99% | No | 150–300 mg |

| Telmisartan | Micardis | 24 h | >99% | 42–58% | 1%/99% | No | 40–80 mg |

| Eprosartan | Teveten | 5 h | 98% | 13% | 30%/70% | No | 400–800 mg |

| Olmesartan | Benicar/Olmetec | 14–16 h | >99% | 29% | 40%/60% | No | 10–40 mg |

| Azilsartan | Edarbi | 11 h | >99% | 60% | 55%/42% | No | 40–80 mg |

Adverse effects

This class of drugs is usually well tolerated.

Serious adverse effects include hyperkalemia, renal failure and hypotension. Those adverse effects are shared by both angiotensin-converting-enzyme inhibitors and angiotensin 2 receptor antagonists.[17]

Common adverse drug reactions include: dizziness, headache, and/or hyperkalemia.

Infrequent adverse drug reactions associated with therapy include: first dose orthostatic hypotension, rash, diarrhea, dyspepsia, abnormal liver function, muscle cramp, myalgia, back pain, insomnia, decreased hemoglobin levels, renal impairment, pharyngitis, and/or nasal congestion.[18]

While one of the main rationales for the use of this class is the avoidance of dry cough and/or angioedema associated with ACE inhibitor therapy, rarely they may still occur. In addition, there is also a small risk of cross-reactivity in patients having experienced angioedema with ACE inhibitor therapy.[18]

Myocardial infarction: controversy resolved

The issue of whether angiotensin II receptor antagonists slightly increase the risk of myocardial infarction (MI or heart attack) is currently being investigated. Some studies suggest ARBs can increase the risk of MI.[19] However, other studies have found ARBs do not increase the risk of MI.[20]

As a consequence of AT1 blockade, ARBs increase angiotensin II levels several-fold above baseline by uncoupling a negative-feedback loop. Increased levels of circulating angiotensin II result in unopposed stimulation of the AT2 receptors, which are, in addition, upregulated. However, recent data suggest AT2 receptor stimulation may be less beneficial than previously proposed, and may even be harmful under certain circumstances through mediation of growth promotion, fibrosis, and hypertrophy, as well as eliciting proatherogenic and proinflammatory effects.[21][22][23]

A 2011 meta analysis found that angiotensin receptor blockers had no effect on the outcome of myocardial infarction, angina pectoris, cardiovascular mortality and total mortality compared to controls (placebo/active treatment), placebo, or active treatment. But they reduced the risk of stroke, heart failure, and new onset diabetes compared with controls, or placebo or with active treatment.[1]

Cancer risk: controversy

A study published in 2010 determined that "...meta-analysis of 5 randomised controlled trials, most on telmisartan, suggests that ARBs are associated with a modestly increased risk of new cancer diagnosis. Given the limited data, it is not possible to draw conclusions about the exact risk of cancer associated with each particular drug. These findings warrant further investigation." [24] A later meta-analysis by the FDA of 31 randomized controlled trials comparing ARBs to other treatment found no evidence of an increased risk of incident (new) cancer, cancer-related death, breast cancer, lung cancer, or prostate cancer in patients receiving ARBs.[25] But the patient-level data included in the analysis are not accessible in the public domain.[26] Two other meta analyses from 2011 didn't find an association with cancer.[27][28] But independent researchers, were unable to obtain the data from the industry-sponsored ATC meta analysis.[26]

Data from 3 observational studies have similarly found no increase in risk of cancer associated with use of angiotensin receptor blockers.[29] Also two retrospective cohort studies from the United States Department of Veterans Affairs on the experience of more than a million Veterans found no increased risk of lung and prostate cancer.[30]

Then, in May 2013, a senior regulator at the Food & Drug Administration, Medical Team Leader Thomas A. Marciniak, announced that the examination of the FDA had failed to include lung carcinoma as a "cancer", and that the results of his investigation going through the raw data, patient by patient, actually showed that lung-cancer risk increased by about 24% in ARB patients, compared with patients taking a placebo or other drugs. He found that in 10 of the 11 studies he examined, there were more lung cancer cases in the ARB-treated patients than in the control group. An article on these findings by Marciniak was published in the Wall Street Journal on May 30, 2013: [31] In the article Ellis Unger, chief of the drug-evaluation division that includes Marciniak, was quoted as calling the complaints a "diversion," and saying in an interview, "We have no reason to tell the public anything new."

Contraindications

- Pregnancy: angiotensin II receptor blockers can cause birth defects. Neonatal complications were more frequent following exposure to ARBs compared to ace inhibitors. Overall 48% of the newborns exposed to ACE-Is and 87% of the newborns exposed to ARBs did exhibit any complication.[32]

- Renal artery stenosis (bilateral or unilateral with a solitary functioning kidney)

- Hyperkalemia

Products

- Valsartan (Diovan) 80-160-320 mg 1x

- Telmisartan (Micardis) 20-40-80 mg 1x

- Losartan (Cozaar) 50–100 mg 1x

- Irbesartan (Aprovel) 75-150-300 mg 1x

- Olmesartan (Benicar) 10-20-40 mg 1x

- Eprosartan (Teveten) 600 mg 1x

- Candesartan (Atacand): 8-16-32 mg 1x

Research

Migraine

ACE inhibitors and ARBs have migraine prophylaxis activity similar to that of some currently utilized agents. Low-dose lisinopril or candesartan may be reasonable second- or third-line agents, particularly in patients with other indications for ACE inhibitor or ARB therapy.[33]

Male sexual dysfunction

ACE-inhibitors, angiotensin-receptor-blockers and calcium-channel-blockers are reported to have no relevant or even a positive effect on erectile function.[34]

Cognitive decline

A network meta-analysis on association between antihypertensive classes, cognitive decline and incidence of dementia supported the notion that antihypertensive treatment has beneficial effects on cognitive decline and prevention of dementia, and indicate that these effects may differ between drug classes with ARBs possibly being the most effective.[35]

References

- ^ a b Bangalore, S. (26 April 2011). "Angiotensin receptor blockers and risk of myocardial infarction: meta-analyses and trial sequential analyses of 147 020 patients from randomised trials". BMJ. 342 (apr26 2): d2234–d2234. doi:10.1136/bmj.d2234.

{{cite journal}}:|access-date=requires|url=(help); Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help)http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3082637/#__ffn_sectitle - ^ Bangalore, S. "Fraudulent Data, an Apology and the Fate of the Angiotensin Receptor Blockers". Retrieved 7 April 2014.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - ^ "lancet-retracts-jikei-heart-study-following-investigation". Retractionwatch. Retrieved 8 April 2014.

- ^ Dykewicz, MS (Aug 2004). "Cough and angioedema from angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors: new insights into mechanisms and management". Current opinion in allergy and clinical immunology. 4 (4): 267–70. PMID 15238791.

- ^ Heran, BS (Oct 8, 2008). "Blood pressure lowering efficacy of angiotensin receptor blockers for primary hypertension". The Cochrane database of systematic reviews (4): CD003822. doi:10.1002/14651858. PMID 18843650.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ Conlin, PR (Apr 2000). "Angiotensin II antagonists for hypertension: are there differences in efficacy?". American journal of hypertension. 13 (4 Pt 1): 418–26. PMID 10821345.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ van Vark, LC (Aug 2012). "Angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors reduce mortality in hypertension: a meta-analysis of randomized clinical trials of renin-angiotensin-aldosterone system inhibitors involving 158,998 patients". European heart journal. 33 (16): 2088–97. PMID 22511654.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ Heran, BS (Apr 18, 2012). "Angiotensin receptor blockers for heart failure". The Cochrane database of systematic reviews. 4: CD003040. PMID 22513909.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ Kuenzli, A (Apr 1, 2010). "Meta-analysis of combined therapy with angiotensin receptor antagonists versus ACE inhibitors alone in patients with heart failure". PloS one. 5 (4): e9946. PMID 20376345.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ a b Makani, H. (28 January 2013). "Efficacy and safety of dual blockade of the renin-angiotensin system: meta-analysis of randomised trials". BMJ. 346 (jan28 1): f360–f360. doi:10.1136/bmj.f360.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ Strippoli, G. F M (9 October 2004). "Effects of angiotensin converting enzyme inhibitors and angiotensin II receptor antagonists on mortality and renal outcomes in diabetic nephropathy: systematic review". BMJ. 329 (7470): 828–0. doi:10.1136/bmj.38237.585000.7C.

- ^ a b Maione, A. (3 March 2011). "Angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors, angiotensin receptor blockers and combined therapy in patients with micro- and macroalbuminuria and other cardiovascular risk factors: a systematic review of randomized controlled trials". Nephrology Dialysis Transplantation. 26 (9): 2827–2847. doi:10.1093/ndt/gfq792.

{{cite journal}}:|access-date=requires|url=(help); Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ Husten, Larry (October 8, 2009). "Lancet retracts COOPERATE trial of dual RAS inhibition and spanks lead author for serious misconduct". CardioBrief.

- ^ Nakao, Naoyuki (January 2003). "RETRACTED: Combination treatment of angiotensin-II receptor blocker and angiotensin-converting-enzyme inhibitor in non-diabetic renal disease (COOPERATE): a randomised controlled trial". The Lancet. 361 (9352): 117–124. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(03)12229-5.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ Naik, Gautam (August 10, 2011). "Mistakes in Scientific Studies Surge". The Wall street journal. Retrieved 13 April 2014.

- ^ "PRAC recommends against combined use of medicines affecting the renin-angiotensin (RAS) system". Retrieved 12 April 2014.

- ^ "Angiotensin II receptor antagonists and heart failure: angiotensin-converting-enzyme inhibitors remain the first-line option". PMID 16285075.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - ^ a b Rossi S, editor. Australian Medicines Handbook 2006. Adelaide: Australian Medicines Handbook; 2006.

- ^ Strauss MH, Hall AS (2006). "Angiotensin receptor blockers may increase risk of myocardial infarction: unraveling the ARB-MI paradox". Circulation. 114 (8): 838–54. doi:10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.105.594986. PMID 16923768.

- ^ Tsuyuki RT, McDonald MA (2006). "Angiotensin receptor blockers do not increase risk of myocardial infarction". Circulation. 114 (8): 855–60. doi:10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.105.594978. PMID 16923769.

- ^ Levy BI (2005). "How to explain the differences between renin angiotensin system modulators". Am. J. Hypertens. 18 (9 Pt 2): 134S–141S. doi:10.1016/j.amjhyper.2005.05.005. PMID 16125050.

- ^ Lévy BI (2004). "Can angiotensin II type 2 receptors have deleterious effects in cardiovascular disease? Implications for therapeutic blockade of the renin-angiotensin system". Circulation. 109 (1): 8–13. doi:10.1161/01.CIR.0000096609.73772.C5. PMID 14707017.

- ^ Reudelhuber TL (2005). "The continuing saga of the AT2 receptor: a case of the good, the bad, and the innocuous". Hypertension. 46 (6): 1261–2. doi:10.1161/01.HYP.0000193498.07087.83. PMID 16286568.

- ^ Sipahi I; Debanne, SM; Rowland, DY; Simon, DI; Fang, JC (2010). "Angiotensin-receptor blockade and risk of cancer: meta-analysis of randomised controlled trials". Lancet Oncol. 11 (7): 627–36. doi:10.1016/S1470-2045(10)70106-6. PMID 20542468.

- ^ "Angiotensin FDA Drug Safety Communication: No increase in risk of cancer with certain blood pressure drugs--Angiotensin Receptor Blockers (ARBs)". U.S. Food and Drug Administration. 2 June 2011.

- ^ a b Egan, G (Sep 2012). "Does outcome reporting bias "cause" cancer? Risks associated with hidden data on Angiotensin receptor blockers". The Canadian journal of hospital pharmacy. 65 (5): 387–93. PMID 23129868.

{{cite journal}}:|access-date=requires|url=(help); Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ ARB Trialists, Collaboration (Apr 2011). "Effects of telmisartan, irbesartan, valsartan, candesartan, and losartan on cancers in 15 trials enrolling 138,769 individuals". Journal of hypertension. 29 (4): 623–35. PMID 21358417.

- ^ Bangalore, S (Jan 2011). "Antihypertensive drugs and risk of cancer: network meta-analyses and trial sequential analyses of 324,168 participants from randomised trials". The lancet oncology. 12 (1): 65–82. PMID 21123111.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ Bhaskaran, K. (24 April 2012). "Angiotensin receptor blockers and risk of cancer: cohort study among people receiving antihypertensive drugs in UK General Practice Research Database". BMJ. 344 (apr24 1): e2697–e2697. doi:10.1136/bmj.e2697.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ Rao GA; Mann, JR; Shoaibi, A; Pai, SG; Bottai, M; Sutton, SS; Haddock, KS; Bennett, CL; Hebert, JR (2010). "Angiotensin receptor blockers: are they related to lung cancer?". J Hypertens. 11 (7): 627–36. doi:10.1097/HJH.0b013e3283621ea3. PMC 3879726. PMID 23822929.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|displayauthors=ignored (|display-authors=suggested) (help) - ^ Thomas M. Burton (30 May 2013). "Dispute flares inside FDA over safety of popular blood-pressure drugs".

- ^ Bullo, M (Aug 2012). "Pregnancy outcome following exposure to angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors or angiotensin receptor antagonists: a systematic review". Hypertension. 60 (2): 444–50. PMID 22753220.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ Gales BJ, Bailey EK, Reed AN, Gales MA (February 2010). "Angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors and angiotensin receptor blockers for the prevention of migraines". Ann Pharmacother. 44 (2): 360–6. doi:10.1345/aph.1M312. PMID 20086184.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Baumhäkel, M. (March 2011). "Cardiovascular risk, drugs and erectile function - a systematic analysis". International Journal of Clinical Practice. 65 (3): 289–298. doi:10.1111/j.1742-1241.2010.02563.x.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ Levi Marpillat, Natacha (June 2013). "Antihypertensive classes, cognitive decline and incidence of dementia". Journal of Hypertension. 31 (6): 1073–1082. doi:10.1097/HJH.0b013e3283603f53.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help)

External links

- Angiotensin+II+Type+1+Receptor+Blockers at the U.S. National Library of Medicine Medical Subject Headings (MeSH)