Assyrian continuity

Assyrian continuity is the theory—supported by a number of scholars and modern Assyrians—that today's modern Assyrians descend from the ancient Assyrians, a Semitic people native to ancient Assyria, that originally spoke ancient Assyrian language, a dialect of Akkadian language, and Aramaic later. Notions of Assyrian continuity are based on both ethnic, genetic, linguistic and historical claims, and the asserted continuity of Assyria's historical and cultural heritage after the fall of the ancient Assyrian Empire.[1][2][3][4]

Claims of continuity have an important place in public life of modern Assyrian communities, both in homeland and throughout the Assyrian diaspora.[5][6][7] Modern Assyrians are accepted to be an indigenous ethnic minority of modern Iraq, southeastern Turkey, northeastern Syria, and border areas of northwestern Iran, a region that is roughly what was once ancient Assyria.[8][9]

Assyrians are a modern people who still speak, read and write Akkadian-influenced[10] Eastern Aramaic dialects, such as Assyrian Neo-Aramaic.[11] Most are Christians,[12] being members of various denominations of Syriac Christianity: the Assyrian Church of the East, Ancient Church of the East, Chaldean Catholic Church, Syriac Orthodox Church, Syriac Catholic Church; as well as the Protestant denominations of the Assyrian Pentecostal Church and the Assyrian Evangelical Church.[13]

There has been a significant contingent of contemporary scholars supporting Assyrian continuity, including Simo Parpola,[14][3][15] Richard Frye,[16][17] Mordechai Nisan,[18] John Brinkman,[19] Robert Biggs,[20] and Henry Saggs.[21] Among Assyrian scholars, one of the most prominent supporters of Assyrian continuity is university professor and Syriac scholar Amir Harrak.[22][23][24]

Evidence for continuity from the Classical Antiquity

Evidence of Assyrian continuity from the period of Classical Antiquity refers to archeological and historical data related to the Assyrian regional, cultural and ethnic continuity during the periods of Neo-Babylonian, Achaemenid, Seleucid, Parthian, Roman, Sassanid and early Byzantine rule (7th century BCE - 7th century CE). In terms of an unbroken continuity of Assyrian regional traditions and identity, one of the main evidence is provided by the survival of Assyrian regional name, that not only outlived the fall of the Assyrian Empire, but was also officially used by some successive states as administrative (provincial) designation for the Assyrian heartlands (see: Achaemenid Assyria, Sassanid Asoristan, and Roman Assyria).[14][3]

Second group of evidence is related to archeological finds from various post-Imperial periods. Modern archeological excavations in the Assyrian heartlands have indicated that there was a substantial continuity of local occupancy, accompanied by preservation of regional and cultural identities, primarily in terms of continuation of main Assyrian religious cults and practices.[25][26][27][28]

Additional questions, that were raised by several authors already during the period of Classical Antiquity, referred to etymological and semantic relations between terms Assyria and Syria. The discovery (1997) of the Çineköy inscription appears to prove the already largely prevailing position that the term "Syria" ultimately derives from the Akkadian term Aššūrāyu (cuneiform script: 𒀸𒋗𒁺𐎹) through apheresis. The Çineköy inscription is a Hieroglyphic Luwian-Phoenician bilingual, uncovered from Çineköy in Adana Province, Turkey (ancient Cilicia), dating to the 8th century BCE.[29] This Indo-European corruption of Assyrian was later adopted by the Seleucid Greeks from the late 4th century BC or early 3rd century BC and also then applied (or misapplied) to non-Assyrian peoples from the Levant, causing not only the true Assyrians (Syrians), but also the largely Aramaean, Phoenician and Nabataean peoples of the Levant to be collectively called "Syrians" or "Syriacs" (Template:Lang-la, Template:Lang-grc) in the Greco-Roman world.

In Classical Greek usage, "Syria" and "Assyria" were used almost interchangeably. Herodotus's distinctions between the two in the 5th century BC were a notable early exception.[30] Randolph Helm has emphasized that Herodotus "never" applied the term Syria to Mesopotamia, which he always called "Assyria", and used "Syria" to refer to inhabitants of the coastal Levant.[31] While himself maintaining a distinction, Herodotus also claimed that "those called Syrians by the Hellenes (Greeks) are called Assyrians by the barbarians (non-Greeks).[32][16][17]

The Greek historian Thucydides reports that during the Peloponnesian wars (c. 410 BC), the Athenians intercepted a Persian who was carrying a message from the Great King to Sparta. The man was taken prisoner, brought to Athens, and the letters he was carrying were translated "from the Assyrian language" which was Imperial Aramaic, an official language first of the former Neo-Assyrian Empire and then a language of diplomacy of the succeeding Achaemenid Persian Empire.

Greek geographer and historian Strabo (d. in 24 CE) described, in his "Geography", both Assyria and Syria, dedicating specific chapters to each of them,[33] but also noted, in his chapter on Assyria:

"Those who have written histories of the Syrian empire say that when the Medes were overthrown by the Persians, and the Syrians by the Medes, they spoke of the Syrians only as those who built the palaces at Babylon and Ninos. Of these, Ninos founded Ninos in Atouria, and his wife Semiramis succeeded her husband and founded Babylon ... The city of Ninos was destroyed immediately after the overthrow of the Syrians. It was much greater than Babylon and was situated in the plain of Atouria."[34]

Throughout his work, Strabo used terms Atouria (Assyria) and Syria (and also terms Assyrians and Syrians) in relation to specific terminological questions, while comparing and analyzing views of previous writers. Reflecting on the works of Posidonius (d. 51 BCE), Strabo noted:

"For the people of Armenia, the Syrians, and the Arabians display a great racial kinship, both in their language and their lives and physical characteristics, particularly where they are adjacent ... Considering the latitudes, there is a great difference between those toward the north and south and the Syrians in the middle, but common condition s prevail, [C42] and the Assyrians and Arameans somewhat resemble both each other and the others. He [Poseidonios] infers that the names of these peoples are similar to each other, for those whom we call Syrians are called Aramaians by the Syrians themselves, and there is a resemblance between this [name], and that of the Arameans, Arabians, and Erembians."[35]

Terms "Syria" and "Assyria" were not fully distinguished by Greeks until they became better acquainted with the Near East. Under Macedonian rule after Syria's conquest by Alexander the Great, "Syria" was restricted to the land west of the Euphrates. While the Romans mostly corrected their usage as well,[36] they and the Greeks continued to conflate the terms.

Jewish historian Flavius Josephus, writing in the 1st century AD about various peoples who were descended from the Sons of Noah, according to Biblical tradition, noted that: "Assyras founded the city of Ninus, and gave his name to his subjects, the Assyrians, who rose to the height of prosperity. Arphaxades named those under his rule Arphaxadaeans, the Chaldaeans of to-day. Aramus ruled the Aramaeans, whom the Greeks term Syrians".[37] Those remarks testify that Josephus regarded all there peoples (Assyrians, Chaldeans, Arameans) as his contemporaries, thus confirming that in his time Assyrians were not considered to be extinct.

Ancient kingdoms of Adiabene, Osroene, Beth Garmai (modern Kirkuk and it's surrounds)and Beth Nuhadra (centered in modern Dohuk) were Neo-Assyrian kingdoms within the Assyrian heartland,[38] continuing its linguistic and cultural traditions, that can be observed particularly among social and political elites of Adiabene.[39]

Justinus, the Roman historian wrote in 300 AD: The Assyrians, who are afterwards called Syrians, held their empire thirteen hundred years.[40]

In the 380s AD, the Roman historian Ammianus Marcellinus during his travels in Upper Mesopotamia with Jovian states that; "Within this circuit is Adiabene, which was formerly called Assyria;" Ammianus Marcellinus also refers to an extant region still called Assyria located between the Tigris and Euphrates rivers.[41]

Reflecting on various meanings of Syrian designations in works of classical authors, modern scholar Nathanael Andrade pointed that some of those uses are indicating the existence of ethnic continuities:

"This shift to "Syrian" as a social regional formulation did not suppress all veins of ethnic Syrianness. The Syrian ethnic articulations of Syrianness that characterized Seleucid times persisted through the Roman imperial period. The previously mentioned examples of Iamblichus and Lucian’s On the Syrian Goddess indicate this, and Strabo and Josephus posited ethnic continuity between Syrians and ancient Assyrians or Arameans."[42]

Evidence for continuity from the Medieval Period and Renaissance

Arab conquest of the Near East during the 7th century CE marked the beginning of gradual Islamization and Arabization of native Christian communities, including Christian Assyrians, who were by that time mainly under the jurisdiction of the ancient Church of the East. During the early period of Muslim rule, terms for Assyria and Assyrians entered Arabic literature. The 10th-century AD Arab scholar Ibn al-Nadim, while describing the books and scripture of many people, defines the word "ʾāšūriyyūn" (Template:Lang-ar) as "a sect of Jesus" inhabiting northern Mesopotamia.[43]

The earliest recorded Western mention of the Christians of the area is by Jacques de Vitry in 1220/1: he wrote that they "denied that Mary was the Mother of God and claimed that Christ existed in two persons. They consecrated leavened bread and used the 'Chaldean' language".[44]

The language that today is usually called Aramaic was called Chaldean by Jerome (c. 347 — 420).[45] This usage continued down the centuries: it was still the normal terminology in the nineteenth century.[46][47][48] Accordingly, in the earliest recorded Western mentions of the Christians of what is now Iraq and nearby countries the term is used with reference to their language. In 1220/1 Jacques de Vitry wrote that "they denied that Mary was the Mother of God and claimed that Christ existed in two persons. They consecrated leavened bread and used the 'Chaldean' (Syriac) language".[44] In the fifteenth century the term "Chaldeans" was first applied to East Syrians no longer generically in reference to their language but specifically to some living in Cyprus who entered a short-lived union with Rome.[49][50]

Following the schism of 1552, Yohannan Sulaqa went to Rome, claiming to have been elected as patriarch of the Church of the East. He made a profession of faith that was there judged to be orthodox, was admitted into communion with the Catholic Church and was consecrated patriarch by Pope Julius III. He returned to Mesopotamia as "Patriarch of the Chaldeans",[51][52][53] or "patriarch of Mosul",[54][55] or "patriarch of the Eastern Assyrians", as stated by Pietro Strozzi on the second-last unnumbered page before page 1 of his De Dogmatibus Chaldaeorum,[56] of which an English translation is given in Adrian Fortescue's Lesser Eastern Churches.[57]

Herbert Chick's "Chronicle of the Carmelites in Persia", which speaks of the Aramaic-speaking Christians generically as Chaldeans, quotes a letter of Pope Paul V to the Persian Shah Abbas I (1571–1629) on 3 November 1612 asking for leniency towards those "who are called Assyrians or Jacobites and inhabit Isfahan".[58]

In his Sharafnama, Sharaf Khan Al-Bedlissi, a 16th-century AD Kurdish historian, mentions Asuri (Assyrians) as being extant in northern Mesopotamia.[59]

Poutrus Nasri, an Egyptian theologian, claims that the Church of the East had many adherents who espoused an Assyrian identity during the Parthian and Sassanid periods.[60]

Scarcity of Assyrian names in the Christian Era

One of the main arguments against the continuity hypothesis is the scarcity of Assyrian and Mesopotamian (East Semitic) pagan personal names among the Assyrian Christian priests, bishops and other religious figures. This argument has been put forward by Jean Maurice Fiey, John Joseph and David Wilmshurst.

Dominican Syriac scholar J. M. Fiey noted that while Eastern Christian writers wrote extensively about Assyrians and Babylonians, they did not identify with them. Fiey comments,

I have made indices of my Assyrie chretienne, and have had to align some 50 pages of proper names of people; there is not a single writer who has an 'Assyrian' name.' Wilmshurst comments, 'The names of thousands of Assyrian and Chaldean Catholic bishops, priests, deacons and scribes between the third and nineteenth centuries are known, and there is not a Sennacherib or Ashurbanipal among them.[61][62][63]

Defenders of the continuity hypothesis have argued that it is usual and common for peoples to adopt biblical names after undergoing Christianisation, particularly as names such as "Sennacherib" and "Ashurbanipal" have clearly pagan connotations, and thus unlikely to be used by Christian priests, and many were in fact throne names or eponyms.[citation needed] Fred Aprim has claimed that distinct Assyrian names continued in an unbroken line from ancient times to the present, giving examples of Assyrian personal names used as late as 238 AD.[64]

Similarly, Odisho Gewargis explained the general scarcity of autochthonous personal names as a process taking place only after Christianisation, when peoples generally replace native names with biblical names; giving as an example of this the scarcity of traditional English names such as "Wolfstan," "Redwald," "Aethelred," "Offa" and "Wystan" among modern Englishmen, compared to the commonality of non-English biblical names such as "John," "Mark," "David," "Paul," "Thomas," "Daniel," 'Michael," "Matthew," "Benjamin," "Elizabeth," "Mary," "Joanne," "Josephine," "Paula," "Rebecca," "Simone," "Ruth" etc. Gewargis also noted: "If the children of Sennacherib were, for centuries, taught to pray and damn Babylon and Assyria, how does the researcher expect from people who wholeheartedly accepted the Christian faith to name their children Ashur and Esarhaddon?"[65] In response, John Joseph strongly criticizes this argument as contradictory with Gewargis's other arguments:

"Contradicting himself, Mr. Gewargis notes that centuries ago, monks and ecclesiastics of the Eastern churches had 'great praise and exaltation for the Assyrians and their kings, their clergy and their judges and obvious downgrading of the prophets, clergy, kings and the elders of Israel. Thus one can say,' he concludes, that Sabhrisho, and monk Yaqqira and patriarch Ishoyabh 'were Assyrians filled with national pride.' We have here an unusual situation: 1. The Church fathers proudly calling themselves 'Aturaye'; 2. The common people, members of the church, for centuries calling themselves 'Suryaye'; 3. And Mr. Gewargis, an Aramaic-language expert who won't tell us the difference between these two Aramaic words, Aturaye and Suryaye."[66]

Many Old English personal names, such as Edward and Audrey, remain popular in England.[67][68]

Early modern opinions favoring continuity

Proponents of continuity such as Stephanie Dalley point out that as late as the 18th and 19th centuries, the region around Mosul was known as "Athura" by the native Christian population, which means "Assyria."[25] A number of 19th century Assyriologists, such as Austen Henry Layard, the Assyrian archaeologist Hormuzd Rassam and the Anglican missionary and orientalist George Percy Badger supported Assyrian continuity.

Christian missionary Horatio Southgate (d. 1894), who travelled through Mesopotamia and encountered various groups of indigenous Christians, stated in 1840 that Chaldeans consider themselves to be descended from Assyrians, but he also recorded that the same Chaldeans hold that Jacobites are descended from those ancient Syrians whose capital city was Damascus. Referring to Chaldean views, Southgate stated:

"Those of them who profess to have any idea concerning their origin, say, that they are descended from the Assyrians, and the Jacobites from the Syrians, whose chief city was Damascus".[69]

Rejecting assumptions of Asahel Grant, who claimed (in 1841) that modern Nestorians and other Christian groups of Mesopotamia are descendants of ancient Jewish tribes,[70] Southgate remarked (in 1842):

"The Syrians are remarkably strict in the observance of the Sabbath as a day of rest, and this is one of a multitude of resemblances between them and the Jews. There are some of these resemblances which are more strongly marked among the Syrians than among the Nestorians, and yet the Syrians are undoubtedly descendants of the Assyrians, and not of the Jews".[71]

Southgate visited Christian communities of the Near East sometime before the ancient Assyrian sites were rediscovered by western archaeologists,[72] and in 1844 he published additional remarks on local traditions of ancient ancestry:

"At the Armenian village of Arpaout, where I stopped for breakfast, I began to make inquiries for the Syrians. The people informed me that there were about one hundred families of them in the town of Kharpout, and a village inhabited by them on the plain. I observed that the Armenians did not know them under the name which I used, Syriani; but called them Assouri, which struck me the more at the moment from its resemblance to our English name Assyrians, from whom they claim their origin, being sons, as they say, of Assour (Asshur)"[73]

In 1849, British archaeologist Austen Layard (d. 1894) noted that among modern inhabitants of the historical region of Assyria there might be those who are descendants of ancient Assyrians:

"I have thought that it might not be uninteresting to give such slight sketches of manners and customs, as would convey a knowledge of the condition and history of the present inhabitants of the country, particularly of those who, there is good reason to presume, are descendants of the ancient Assyrians. They are, indeed, as much the remains of Nineveh, and Assyria, as are the rude heaps and ruined palaces."[74]

Elaborating further, Layard also noted that local Christian communities, Chaldeans and Jacobites, might be the only remaining descendants of ancient Assyrians:

"A few Chaldaeans and Jacobite Christians, scattered in Mosul and the neighboring villages, or dwelling in the most inaccessible part of the Mountains, their places of refuge from the devastating bands of Tamerlane, are probably the only descendants of that great people which once swayed, from these plains, the half of Asia."[75]

Reflecting on the question of ancient Assyrian heritage in the region, Layard formulated his views on Assyrian continuity:

"Still there lingered, in the villages and around the site of the ruined cities, the descendants of those who had formerly possessed the land. They had escaped the devastating sword of the Persians, of the Greeks, and of the Romans. They still spoke the language of their ancestors, and still retained the name of their race."[76]

English priest Henry Burgess, writing in the early 1850s, states that Upper Mesopotamia was known as Assyria/Athura by the Semitic Christian population of the region.[77]

Ely Bannister Soane wrote in 1912, "The Mosul people, especially the Christians are very proud of their city and the antiquity of its surroundings; the Christians, regard themselves as direct descendants of the great rulers of Assyria."[78]

Sidney Smith argued in 1926 that poor communities continued to perpetuate some basic Assyrian identity after the fall of the empire through to the present.[Note 1] Efrem Yildiz echoes this view also.[80]

Anglican missionary Rev. W. A. Wigram, in his book The Assyrians and Their Neighbours (1929), writes "The Assyrian stock, still resident in the provinces about the ruins of Nineveh, Mosul, Arbela, and Kirkuk, and seem to have been left to their own customs in the same way".[81]

R. S. Stafford in 1935 describes the Assyrians as descending from the Ancient Assyrians, surviving the various periods of foreign rule intact, and until World War I of having worn items of clothing much like the ancient Assyrians.[82]

Modern views

Opposition

Some academics, including the Assyrian historian John Joseph, largely reject the modern Assyrian claim of descent from the ancient Assyrians of Mesopotamia, and their succeeding the Sumero-Akkadians and the Babylonians as one continuous civilization.[83] He criticises modern Assyrian writers who "eager to establish a link between themselves and the ancient Assyrians, conclude that such a link is confirmed whenever they come across a reference to the word Assyrians during the early Christian period, to them it proves that their Christian ancestors always 'remembered' their Assyrian forefathers. Nationalist writers often refer to Tatian's statement that he was 'born in the land of the Assyrians,' and note that the Acts of Mar Qardagh trace the martyr's ancestry to Ancient Assyrian kings".[84] He claims that while "The name Assyrian was certainly used prior to the nineteenth century . . . [it] was a well known name throughout the centuries and wherever the Bible was held holy, whether in the East or West", due to the Old Testament.[66] However, the terms 'Assyria' and 'Assyrian' were only applied to people living within historical Assyria, and not, for example, to Levantine or Arabian persons or peoples.

Adam H. Becker, Professor of Classics & Religious Studies at New York University, disagrees with Assyrian continuity and writes that the special continuity claims "must be understood as a modern invention worthy of the study of a Benedict Anderson or an Eric Hobsbawm rather than an ancient historian." (Both Anderson and Hobsbawm study the origins of invented traditions in nationalism.) Becker describes Assyrians as "East Syrians" in his writings.[85]

David Wilmshurst, a historian of the Church of the East, believes that Assyrian identity only emerged as a consequence of the earlier archaeological discovery of the ruins of Nineveh in 1845.[86] Any continuity, he argues, is insignificant, if it exists at all.

Support

Another argument is based on the etymology of "Syria." The noted Iranologist Richard Nelson Frye, who supports ethnic continuity from ancient times to the present, argues that the term 'Syrian' originating from 'Assyrian' supports continuity, particularly when applied to the Semites in northern Mesopotamia and its environs. In a response to John Joseph, Frye writes "I do not understand why Joseph and others ignore the evidence of Armenian, Arab and Persian sources in regard to usage with initial a-, including contemporary practice."[87] Historian Robert Rollinger also uses this line of argumentation in support of the notion that "Syria" was derived from "Assyria", pointing to the evidence provided by the newly discovered Çineköy inscription.[88][89] Joseph was long skeptical about the initial a-theory, using it as a central plank in his argument against continuity, but has since been forced to accept it following the discovery of the Çineköy inscription.

Prominent Assyriologist Henry Saggs in his book The Might That Was Assyria points out that the Assyrian population was never wiped out, bred out or deported after the fall of its empire, and that after Christianization the Assyrians have continued to keep alive their identity and heritage.[90] However, Saggs disputes an extreme "racial purity"; he points out that even at its mightiest, Assyria deported populations of Jews, Elamites, Arameans, Luwians, Urartians and others into Assyria, and that these peoples became "Assyrianised" and were absorbed into the native population.

Assyriologist John A. Brinkman argues that there is absolutely no historical or archaeological evidence or proof to suggest the population of Assyria was wiped out, bred out of existence or removed at any time following the destruction of its empire. He puts the burden of proof upon those arguing against continuity to prove their case with strong evidence. Brinkman goes on to mention that the gods of the Assyrian Pantheon were certainly still being worshiped even 900 years after the fall of the Assyrian Empire. He also indicated that Assur and Calah, among other cities, were prosperous and still occupied by Assyrians, which he claims indicates a continuity of Assyrian identity and culture well into the Syriac Christian period.[91][92][93]

British archeologist John Curtis disputed assumptions based on non historical biblical interpretations that Assyria became an uninhabited wasteland after its fall, pointing out its wealth and influence during the various periods of Persian rule.[27][28] Modern archeological finds in the Assyrian heartland have indicated that Achaemenid Assyria was a prosperous region.[26] Assyrians soldiers were a remnant of Achaemenid armies, holding important civic positions, with their agriculture providing a breadbasket for the empire. Imperial Aramaic and Assyrian administrative practices were also retained by the Achaemenid kings. In addition, it is known that a number of important Assyrian cities such as Erbil, Guzana and Harran survived intact, and others, such as Assur and Arrapha, recovered from their previous destruction. For those cities that remained devastated, such as Nineveh and Calah, smaller towns were built nearby, such as Mepsila.[94]

French Assyriologist Georges Roux notes that Assyrian culture and national religion were alive into the 3rd and 4th centuries AD, with the city of Assur possibly being independent for some time in the 3rd century AD, and that the Neo-Assyrian kingdom of Adiabene was a virtual resurrection of Assyria, but emphasises that "the revived settlements [in ancient Assyria] had very little in common architecturally with their earlier precursors."[95] Roux also states that, "After the fall of Assyria, however, its actual name was gradually changed to 'Syria'; thus, in the Babylonian version of Darius I inscriptions, Eber-nari ("across-the-river," i.e. Syria, Palestine and Phoenicia) corresponds to the Persian and Elamite Athura (Assyria); besides, in the Behistun inscription, Izalla, the region of Syria renowned for its wine, is assigned to Athura."[citation needed] Roux, as well as Saggs, note that a time came when Akkadian inscriptions were meaningless to the inhabitants of Assyria, and ceased to be spoken by the common people.[96][97][98]

The historian W. W. Tarn states also that Assyrians and their culture were still extant well into the Christian period.[99][100]

Patricia Crone and Michael Cook state that Assyrian consciousness did not die out after the fall of its empire, asserting that a major revival of Assyrian consciousness and culture took place between the 2nd century BC and 4th century AD.[101]

Some supporters of Assyrian continuity, though not all, argue that Assyrian culture as well as ethnicity is continuous from ancient times until today. The Assyriologist Simo Parpola echoes Saggs, Brinkman and Biggs, saying that there is strong evidence that Assyrian identity and culture continued after the fall of the Assyrian Empire.[14][3] Parpola asserts that traditional Assyrian religion remained strong until the 3rd and 4th centuries AD, surviving among small communities of Assyrians up to at least the 10th century AD in Upper Mesopotamia, and as late as the 18th century AD in Mardin, based on accounts of Carsten Niebuhr.[102] Parpola asserts that the Neo-Assyrian Upper Mesopotamian kingdoms of Adiabene, Assur, Osrhoene, Beth Nuhadra, Beth Garmai and to some degree Hatra which existed between the 1st century BC and 5th century AD in Assyria, were distinctly Assyrian linguistically, as they wrote in the Syriac language, a dialect of Aramaic which began in geographic Assyria[1].

Similarly, British linguist Judah Segal pointed to several historical sources from the period of Late Antiquity, containing references to contemporary Assyrians in various regions, from Adiabene to Edessa. He noted that Assyrian designations were used by Tatian, and Lucian of Samosata in his work "On the Syrian Goddess", and also by Christian authors in the later "Doctrine of Addai".[103]

Robert D. Biggs supports genealogical/ethnic continuity without prejudicing cultural continuity, asserting that the modern Assyrians are likely ethnic descendants of ancient Assyrians but became largely culturally different from them with the advent of Christianity.[104]

British writer Tom Holland in an article in The Daily Telegraph of 2017 clearly links the modern Assyrians to the ancient Assyrians, stating that they are the Christianised ancestors of the ancient Assyrians.[105]

Philip Hitti states that "Syrian", "Syriac Christian" and "Nestorian" are simply vague generic terms encompassing a number of different peoples, and that the Semitic Christians of northern Mesopotamia are historically and ethnically most appropriately described as "Assyrians."[106]

Kevin B. MacDonald asserts that Assyrians have survived as an ethnic, linguistic, religious and political minority from the fall of the Assyrian Empire through to the present day. He points out that maintaining a language, religion, identity and customs distinct from their neighbours has aided their survival.[107][108]

William Warda, himself an Assyrian writer, also espouses a continuity from the fall of the Assyrian Empire, through the period of Christianisation and into modern times.[citation needed]

George V. Yana asserts that the Assyrians continue to exist to this day, and shared their culture with Aramaic-speaking populations.[109]

Professor Joshua J. Mark supports a continuity, stating in the Ancient History Encyclopedia, "Assyrian history continued on past that point (the fall of its empire); there are still Assyrians living in the regions of Iran and Iraq, and elsewhere, in the present day."[110]

French film maker Robert Alaux produced a documentary film about the Assyrian Christians in 2004, and states they are descendants of the Ancient Assyrians-Mesopotamians, and were among the very earliest people to convert to Christianity.[111]

Differences between Assyrians and neighbouring peoples

Wolfhart Heinrichs differentiates between Levantine Aramaean and Mesopotamian Assyrian populations, stating that; "even if 'Syrian' were derived from 'Assyrian', it does not mean that the people and culture of geographical Syria are identical to those of geographical Assyria".[112]

The Unrepresented Nations and Peoples Organization (UNPO) recognises Assyrians as indigenous people of northern Iraq.[113]

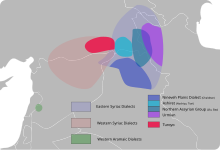

Genetic continuity

A series of modern genetic studies have shown that the modern Assyrians from northern Iraq, southeastern Turkey, northwestern Iran and northeastern Syria are in a genetic sense one homogenous people, regardless of which church they belong to (e.g. Assyrian Church of the East, Chaldean Catholic, Syriac Orthodox, Assyrian Protestant). Their collective genetic profile differs from neighbouring Syrians, Levantine Syriac Arameans, Kurds/Iranians, Arabs, Turks, Armenians, Jews, Yezidis, Shabaks, Greeks, Georgians, Circassians, Turcomans, Maronite Christians, Egyptians and Mandaeans.[114][115][116][117][118]

Late 20th century DNA analysis conducted on Assyrian members of the Assyrian Church of the East, Chaldean Catholic Church and Syriac Orthodox Church by Cavalli-Sforza, Paolo Menozzi and Alberto Piazza "shows that Assyrians have a distinct genetic profile that distinguishes their population from any other population."[114][119] Genetic analysis of the Assyrians of Persia demonstrated that they were "closed" with little "intermixture" with the Muslim Persian population and that an individual Assyrian's genetic makeup is relatively close to that of the Assyrian population as a whole.[115] Cavalli-Sforza et al. state in addition, "[T]he Assyrians are a fairly homogeneous group of people, believed to originate from the land of old Assyria in northern Iraq," and "they are Christians and are probably bona fide descendants of their namesakes."[116] "The genetic data are compatible with historical data that religion played a major role in maintaining the Assyrian population's separate identity during the Christian era."[114]

A 2008 study on the genetics of "old ethnic groups in Mesopotamia," including 340 subjects from seven ethnic communities (Assyrian, Jewish, Zoroastrian, Armenian, Turcoman, Kurdish and Arab peoples of Iran, Iraq, and Kuwait) found that Assyrians were homogeneous with respect to all other ethnic groups sampled in the study, regardless of each Assyrians religious affiliation.[Note 2]

A study by Dr Joel J. Elias found that Assyrians of all denominations were a homogenous group, and genetically distinct from all other Near Eastern ethnicities.[114]

In a 2006 study of the Y chromosome DNA of six regional populations, including, for comparison, Assyrians and Syrians, researchers found that "the Semitic populations (Assyrians and Syrians) are very distinct from each other according to both [comparative] axes. This difference supported also by other methods of comparison points out the weak genetic affinity between the two populations with different historical destinies."[118]

In 2008, Fox News in the United States ran a feature called "Know Your Roots." As part of the feature, Assyrian reporter Nineveh Dinha was tested by GeneTree.com. Her DNA profile was traced back to the region of Harran in southeastern Anatolia in 1400 BC, which was a part of ancient Assyria.[120]

In a 2011 study focusing on the genetics of Marsh Arabs in Iraq, researchers identified Y chromosome haplotypes shared by Marsh Arabs, Arabic-speaking Iraqis, Mandaeans and Assyrians, "supporting a common local background."[Note 3]

A 2017 study of the various ethnic groups of Iraq appeared to show that Assyrians (along with Mandaeans and Yazidis) have a stronger genetic connection to the population extant during the period of Bronze Age and Iron Age Mesopotamia than their neighbours, the Arabs, Kurds, Turks, Iranians, Armenians and Turcomans.[122]

A study by Akbari et al supports the genetic distinctiveness of the Assyrian people in relation to their neighbours, and notes their ancient origins in the region[2]

Linguistic continuity

Among Assyrians, numbers of fluent speakers range from approximately 600,000 to 1,000,000, with the main dialects being Assyrian Neo-Aramaic (250,000 speakers), Chaldean Neo-Aramaic (216,000 speakers) and Surayt/Turoyo (112,000 to 450,000 speakers), together with a number of smaller, closely related dialects with no more than 10,000 speakers between them. Contrary to what their names suggest, these mutually intelligible dialects are not divided upon Assyrian Church of the East/Chaldean Catholic Church/Syriac Orthodox Church/Assyrian Protestant/Syriac Catholic Church lines.[123][124]

By the 3rd century AD at the very latest, Akkadian was extinct, although significantly, some loaned vocabulary, grammatical features and family names still survives in the Eastern Aramaic dialects of the Assyrians to this day.[10]

As linguist Geoffrey Khan points out that a number of vocabulary and grammatical features in the colloquial modern neo-Aramaic dialects spoken by the Assyrians shows similarities with the ancient Akkadian language, whereas significantly, the now near extinct Western Aramaic dialects of the Aramaeans, Phoenicians, Nabataeans, Jews and Levantine Syriacs of Syria and the Levant do not.[125] This indicates that the Assyrian Eastern Aramaic dialects gradually replaced Akkadian among the Assyrian populace, and that they were both influenced by and overlaid the earlier Assyrian Akkadian tongue of the region, unlike Aramaic dialects spoken in the Levant.[126]

Similarly, linguists Alda Benjamen and Andrew Breiner also note the Akkadian ( also known as Old Assyrian, Old Babylonian) and Sumerian sub stratum and influences on modern Assyrian dialects that are absent from other dialects of Aramaic and other West Asian languages, and indicates the speakers of these dialects are the same people that once spoke Akkadian[3].

There are a number of Akkadian words mostly connected with agriculture that have been preserved in modern Syriac vernaculars. One example is the word miššara 'rice paddy field' which is a direct descendant of the Akkadian mušāru. A number of words in the dialect of Bakhdida (Qaraqosh) shows the same origin, e.g. baxšimə 'storeroom (for grain)' from Akkadian bīt ḫašīmi 'storehouse' and raxiṣa 'pile of straw' from raḫīṣu 'pile of harvest produce'.[127]

Simo Parpola asserts that Eastern Aramaic had become so entrenched in Assyrian identity that the Greeks regarded the Imperial Aramaic of the Achaemenid Empire during the 5th and 4th centuries BC as "the Assyrian Language."[Note 4] During the 3rd century BC composition of the Septuagint, a translation of the Hebrew Bible into Greek for the Hellenised Jewish community of Alexandria, "Aramaic language" was translated into "Syrian tongue," and "Aramaeans" into "Syrians".[128]

Parpola's assertions are also supported by professor of Semitic languages Alan Millard who states "Those (Aramaic texts) engraved on hard surfaces tend to be formal, but the notes scratched on clay tablets and the few ostraca reveal more cursive forms. From them descended the standard handwriting of the Persian period (called 'Assyrian writing' in Egyptian) and eventually both the square Hebrew script (also known as 'Assyrian writing' in Hebrew), and through Nabataean, the Arabic alphabet."[129]

It is believed that all extant forms of Aramaic stem from Imperial Aramaic, which itself originated in Assyria.[130]

Speaking Aramaic long ago ceased to signify an Aramaean ethnic identity, for the language spread among many previously non-Aramaean and non-Aramaic-speaking peoples in the Near East and Asia Minor from the time of the Neo-Assyrian Empire onwards. Korean orientalist Chul-hyun Bae of Seoul National University states "The Arameans' political power thus came to an end; however, their language survived, ironically achieving a far wider presence that the people among whom it had originated".[131]

Political issues

The Israeli orientalist Mordechai Nisan also supports the view that Assyrians should be named specifically as such in an ethnic and national sense, are the descendants of their ancient namesakes, and are denied self-expression for political, ethnic and religious reasons.[18]

Sargon Donabed notes that Assyrians have been downplayed, denied and under represented in studies on modern Iraq and Turkey due to racial and religious prejudice, and also that the confusion of later religious denominational names applied to them has harmed their cause[4].

Dr Arian Ishaya, an historian and anthropologist from UCLA states that the confusion of names applied to the Assyrians, and a denial of Assyrian identity and continuity, is on one hand borne out of 19th and early 20th century imperialistic, condescending and arrogant meddling by westerners, rather than by historical fact, and on the other hand by long held Islamic, Arab, Kurdish, Turkish and Iranian policies, whose purpose is to divide the Assyrian people along false lines and deny their singular identity, with the aim of preventing the Assyrians having any chance of unity, self-expression and potential statehood.[132]

Naum Faiq, a 19th century advocate of Assyrian nationalism from the Syriac Orthodox Church community in Diyarbakır, encouraged Assyrians to unite regardless of tribal and theological differences.[133] Ashur Yousif, an Assyrian Protestant from the same region of southeastern Turkey as Faiq, also espoused Assyrian unity during the early 20th century, stating that the Church of the East, Chaldean Catholic and Syriac Orthodox were one people, divided purely upon religious lines.[134] Freydun Atturaya also advocated Assyrian unity and was a staunch supporter of Assyrian identity and nationalism and the formation of an ancestral Assyrian homeland in the wake of the Assyrian genocide.[135] Farid Nazha, an influential Syrian-born Assyrian nationalist, deeply criticised the leaders of the various churches followed by the Assyrian people, accusing the Syriac Orthodox Church, Church of the East, Chaldean Catholic Church and Syriac Catholic Church of creating divisions among Assyrians, when their joint ethnic and national identity should be paramount.[136][137] Assyrian doctor George Habash asserts that the Assyrian people have been denied representation due to a betrayal by Western powers and by policy of deliberately denying their heritage and rights by Muslim Arab, Turkish, Iranian and Kurdish regimes.[138]

Nestorian designations

In Christian denominational terminology, both medieval and early modern, it was customary to label the Church of the East as the "Nestorian Church", and its adherents, including Assyrians, as "Nestorians". Kelly L. Ross notes that the oldest western reference to the 'Christians' of Iraq is as "Nestorians," a term used by Cosmas Indicopleustes in 525 AD, though she acknowledges that this is a 'doctrinal' term and not an ethnic one. Hannibal Travis, in contrast, argues that "Assyrian" is the oldest name for this community, and that the term long predated Nestorian.[83] Artur Boháč, Fellow at the Center for Non-Territorial Autonomy at the University of Vienna, echoes Hannibal Travis in arguing that the confusion of later names applied to the Assyrians were introduced by Western theologians and missionaries, and others arose out of doctrinal rather than ethnic divisions.[139][140][141]

Historian David Gaunt states that there was no consensus among English-language sources what term to use for the ethnic group in the early twentieth century; the term "Assyrian" had only been accepted for followers of the Assyrian Church of the East, Syriac Orthodox Church and Chaldean Catholic Church who were extant in Iraq, southeast Turkey, northeast Syria and Northwest Iran Furthermore, since the Ottoman Empire was organized by religion, "Assyrian was never used by the Ottomans; rather, government and military documents referred to their targets by their traditional religious sectarian names".[142]

All adherents of the Assyrian Church of the East and it's offshoot, the Chaldean Catholic Church, reject the label of "Nestorian" even in a theological sense, since the ancient Church of the East certainly predates Nestorianism by centuries, and is doctrinally distinct. Philip Hitti stated that "Nestorian" is an inaccurate term both chronologically and theologically and has no ethnic meaning as it applied to Christians as far afield as China, Central Asia, India and Greece,[140] while Sebastian Brock indicated that Nestorian designations were a lamentable misnomer.[143]

Chaldean identity

In recent times, a mainly United States-based minority[citation needed] within the Chaldean Catholic Church has begun to espouse a separate 'Chaldean' ethnic identity. They assert that they are a different and separate ethnicity compared to modern Assyrians, and are the direct descendants of the ancient Chaldeans of southern Mesopotamia.[citation needed] As a compromise between the two positions, some have chosen to be referred to by the label 'Chaldo-Assyrian' or 'Assyro-Chaldean'.[144]

Chaldean Catholics are members of the largest church that traces its origins from the Church of the East.[145] For many centuries, the term "Chaldean" indicated the Aramaic language. It was so used by Jerome,[45] and was still the normal terminology in the nineteenth century.[46][47][48] Only in 1445 did it begin to be used to mean Aramaic speakers who had entered communion with the Catholic Church. This happened at the Council of Florence,[146] which accepted the profession of faith that Timothy, metropolitan of the Chaldeans in Cyprus, made in Aramaic, and which decreed that "nobody shall in future dare to call [...] Chaldeans, Nestorians".[147][49][50]

Previously, when there were as yet no Catholic Aramaic speakers of Mesopotamian origin, the term "Chaldean" was applied with explicit reference to their "Nestorian" religion. Thus Jacques de Vitry wrote of them in 1220/1 that "they denied that Mary was the Mother of God and claimed that Christ existed in two persons. They consecrated leavened bread and used the 'Chaldean' (Syriac) language".[44]

In an interview published in 2003 with Raphael I Bidawid, head of the Chaldean Catholic Church between 1989 and 2003, he commented on the Assyrian name dispute and distinguished between what is the name of a church and an ethnicity:

I personally think that these different names serve to add confusion. The original name of our Church was the 'Church of the East' ... When a portion of the Church of the East became Catholic, the name given was 'Chaldean' based on the Magi kings who came from the land of the Chaldean, to Bethlehem. The name 'Chaldean' does not represent an ethnicity... We have to separate what is ethnicity and what is religion... I myself, my sect is Chaldean, but ethnically, I am Assyrian.[148]

Proponents of a Chaldean continuity or separateness from Assyrians sometimes claim that they are separate because they speak Chaldean Neo-Aramaic rather than Assyrian Neo-Aramaic.[citation needed] However, both of these appellations are only 20th-century labels applied by some modern linguists to regions where one church was seen to be more prevalent than another for convenience, with no historical continuity or ethnic context implied in either. They are also inaccurate; many speakers of Chaldean Neo-Aramaic are in fact members of the Assyrian Church of the East, Assyrian Pentecostal, Evangelical Churches or Syriac Orthodox Church,[149] and equally, many speakers of Assyrian Neo-Aramaic are members of the Chaldean Catholic Church, the Syriac Orthodox Church, the Syriac Catholic Church or other confessions. This is also true of the Surayt/Turoyo dialect, and minority dialects such as Hértevin, Koy Sanjaq Surat, Bohtan Neo-Aramaic and Senaya. Furthermore, each of these dialects originated in Assyria, evolving from the 8th century BC Imperial Aramaic of the Assyrian Empire and 5th century BC Syriac of Achaemenid Assyria.

See also

Notes

- ^ "In Achaemenian times there was an Assyrian detachment in the Persian army, but they could only have been a remnant. That remnant persisted through the centuries to the Christian era and beyond, and continued to use in their personal names appellations of their pagan deities. This continuance of an Assyrian tradition is significant for two reasons; the miserable conditions of these late Assyrians is attested to by the excavations at Ashur, and it is clear that they were reduced to extreme poverty by the time of Parthian rule."[79]

- ^ "The relationship probability was lowest between Assyrians and other communities. Endogamy was found to be high for this population through determination of the heterogeneity coefficient (+0,6867), Our study supports earlier findings indicating the relatively closed nature of the Assyrian community as a whole, which as a result of their religious and cultural traditions, have had little intermixture with other populations."[117]

- ^ "In the less frequent J1-M267* clade, only marginally affected by events of expansion, Marsh Arabs shared haplotypes with other Iraqi and Assyrian samples, supporting a common local background."[121]

- ^ 'The Greek historian Thucydides reports that during the Peloponnesian wars (ca. 410 BC) the Athenians intercepted a Persian who was carrying a message from the Great King to Sparta. The man was taken prisoner, brought to Athens, and the letters he was carrying were translated "from the Assyrian language", which of course was Aramaic…'

References

- ^ Yildiz 1999, p. 16-19.

- ^ Gewargis 2002, p. 77–95.

- ^ a b c d Parpola 2004, p. 5-22.

- ^ Yana 2008, p. 19-60.

- ^ "Iraqi Christians' long history". BBC News. November 2010.

- ^ "8 things you didn't know about Assyrian Christians". 2015-03-21.

- ^ "Who are the Assyrians? 10 Things to Know about their History & Faith".

- ^ "UNPO: Assyria".

- ^ "Iraqi Christians' long history". BBC News. November 2010.

- ^ a b Kaufman 1974.

- ^ Khan 2012, p. 173-199.

- ^ Hanish 2015, p. 517.

- ^ Wolk 2008, p. 108.

- ^ a b c Parpola 2000, p. 1–16.

- ^ "Assyrian Identity in Ancient Times and Today by Dr. Simo Parpola". atour.com. Retrieved 2019-10-20.

- ^ a b Frye 1992, p. 281–285.

- ^ a b Frye 1997, p. 30–36.

- ^ a b Nisan 2002.

- ^ Assyrian Academic Society: Summary of the Lecture

- ^ Biggs 2005, p. 1–23.

- ^ Saggs 1984.

- ^ Harrak 2001, p. 168-189.

- ^ Harrak 2005, p. 45-65.

- ^ Amir Harrak (2019): Assyrians of the 12th Century AD

- ^ a b Dalley 1993, p. 134–147.

- ^ a b Kuhrt 1995, p. 239-254.

- ^ a b Curtis 2003, p. 157-167.

- ^ a b Curtis 2005, p. 175-195.

- ^ Tekoğlu et al. 2000, p. 961-1007.

- ^ Dalley & Reyes 1998, p. 94.

- ^ Joseph 2000, p. 21.

- ^ (Pipes 1992), s:History of Herodotus/Book 7

Herodotus. "Herodotus VII.63".VII.63: The Assyrians went to war with helmets upon their heads made of brass, and plaited in a strange fashion which is not easy to describe. They carried shields, lances, and daggers very like the Egyptian; but in addition they had wooden clubs knotted with iron, and linen corselets. This people, whom the Hellenes call Syrians, are called Assyrians by the barbarians. The Babylonians served in their ranks, and they had for commander Otaspes, the son of Artachaeus.

Herodotus, Herodotus VII.72,VII.72: In the same fashion were equipped the Ligyans, the Matienians, the Mariandynians, and the Syrians (or Cappadocians, as they are called by the Persians).

- ^ Roller 2014, p. 689-699, 699-713.

- ^ Roller 2014, p. 689-690.

- ^ Roller 2014, p. 71.

- ^ Joseph 1997, p. 38.

- ^ Thackeray 1961, p. 71.

- ^ Harrak 1992, p. 209-214.

- ^ Crone & Cook 1977, p. 55.

- ^ The Origins of Syrian Nationhood: Histories, Pioneers and Identity Adel Beshara

- ^ Ammianus Marcellinus. XXIII.6.20 and XXXIII.3.1

- ^ Andrade 2013, p. 110.

- ^ The Fihrist (Catalog): A Tenth Century Survey of Islamic Culture. Abu 'l Faraj Muhammad ibn Ishaq al Nadim. Great Books of the Islamic World. Kazi Publications. Translator: Bayard Dodge.

- ^ a b c Baum & Winkler 2003, p. 83.

- ^ a b Gallagher 2012, p. 123-141.

- ^ a b Gesenius & Prideaux-Tregelles 1859.

- ^ a b Fürst 1867.

- ^ a b Davies 1872.

- ^ a b Baum & Winkler 2003, p. 112.

- ^ a b O’Mahony 2006, p. 526-527.

- ^ Tisserant 1931, p. 228.

- ^ Baumer 2006, p. 248.

- ^ Healey 2010, p. 45.

- ^ Frazee 2006, p. 57.

- ^ Wilmshurst 2019, p. 194.

- ^ Pietro Strozzi (1617). De dogmatibus chaldaeorum disputatio ad Patrem ... Adam Camerae Patriarchalis Babylonis ... ex typographia Bartholomaei Zannetti.

- ^ A Chronicle of the Carmelites in Persia (Eyre & Spottiswoode 1939), vol. I, pp. 382–383

- ^ H. Chick: A Chronicle of the Carmelites in Persia (Eyre & Spottiswoode, 1939), vol. I, pp. 198–199

- ^ Sharafnameh", translated by Jamil Rozbeyati, Al-Najah Publishing house, Baghdad – 1953

- ^ see Poutrus Nasri (1974). History of Syriac Literature. Cairo.

- ^ Fiey 1965, p. 146-148.

- ^ Joseph 1998, p. 70-76.

- ^ Wilmshurst 2011, p. 415.

- ^ Timeline of Assyrian Continuity

- ^ Gewargis 2002, p. 89.

- ^ a b Joseph 2003.

- ^ Campbell, Mike. "Meaning, origin and history of the name Edward". Behind the Name.

- ^ Campbell, Mike. "Meaning, origin and history of the name Audrey". Behind the Name.

- ^ Southgate 1840, p. 179.

- ^ Grant 1841.

- ^ Southgate 1842, p. 249.

- ^ Donabed 2012, p. 411.

- ^ Southgate 1844, p. 80.

- ^ Layard 1849a, p. IX-X.

- ^ Layard 1849a, p. 38.

- ^ Layard 1849a, p. 241.

- ^ Burgess, Henry. The Repentance of Nineveh. Sampson Low: Son and Co., London, (1853) p.36.

- ^ Soane, E.B. To Mesopotamia and Kurdistan in Disguise. John Murray: London, 1912. p. 92.

- ^ S. Smith, "Notes on the Assyrian Tree". Bulletin of the School of Oriental and African Studies (1926): 69.

- ^ Yildiz 1999, p. 15-30.

- ^ Wigram 1929.

- ^ The Tragedy of the Assyrians. Lt. Col. R.S. Stafford D.S.O., M.C.

- ^ a b Refugee Camps and the Spatialization of Assyrian Nationalism in Iraq The rising European missionary presence in the Hakkari region coincided with a number of archeological excavations of the ancient ruins of Nineveh and Babylon, and especially with the discovery of the Nimrud palace of Ashur-nasirpalii in 1848. Missionaries drew on these recent discoveries of pre-Islamic Assyrian greatness to promote the idea of this branch of eastern Christians as direct descendants of this ancient empire. It was during the late nineteenth century that western missionaries also began to popularise the word Assyrian previously the most prominent of a number of mostly religious designations, as a mode of identifying the present-day community with the ancient empires. Originally, this idea may have been suggested by local assistants to the excavations like the Assyrian activist Hormuzd Rassam; certainly it buttressed community ambitions for local autonomy, as well as romantic missionary imaginings of an untouched "original" Christian community.

- ^ The ancestry of the semi-legendary Mar Qardagh is dubious. (Miller/Joseph)

- ^ Becker 2008, p. 396.

- ^ Wilmshurst 2011, pp. 413–416.

- ^ Frye 1999, p. 70.

- ^ Rollinger 2006a, p. 72-82.

- ^ Rollinger 2006b, p. 283-287.

- ^ Saggs 1984, p. 290:"The destruction of the Assyrian Empire did not wipe out its population. They were predominantly peasant farmers, and since Assyria contains some of the best wheat land in the Near East, descendants of the Assyrian peasants would, as opportunity permitted, build new villages over the old cities and carried on with agricultural life, remembering traditions of the former cities. After seven or eight centuries and after various vicissitudes, these people became Christians. These Christians, and the Jewish communities scattered amongst them, not only kept alive the memory of their Assyrian predecessors but also combined them with traditions from the Bible."

- ^ Assyrian Academic Society: Summary of the Lecture - Quote from a lecture held in 1999 by historian John A. Brinkman: "There is no reason to believe that there would be no racial or cultural continuity in Assyria since there is no evidence that the population of Assyria was removed."

- ^ Al-Jeloo 1999.

- ^ Yildiz 1999, p. 22.

- ^ Printed in Nabu Magazine, Vol. 3, Issue 1 (1997).

- ^ George Roux. Iraq.

- ^ Ancient Iraq (1992 edition), pp.411–412, 419–420, 423–424

- ^ Saggs 1984, p. 125.

- ^ Toynbee, A Study of History (1954), viii, pp. 440–442

- ^ Cambridge Ancient History: The Roman Republic, 133–44 B.C.

- ^ W. W. Tarn; Cambridge University Press; 1985; pp 597.

- ^ Crone & Cook 1977, p. 55

- ^ "Assyrian Identity In Ancient Times And Today'" (PDF). Retrieved 2018-06-16.

- ^ Segal 1970, p. 47, 51, 68-70.

- ^ Biggs 2005, p. 10:"Especially in view of the very early establishment of Christianity in Assyria and its continuity to the present and the continuity of the population, I think there is every likelihood that ancient Assyrians are among the ancestors of modern Assyrians of the area."

- ^ Holland, Tom (5 March 2015). "Islamic State's thugs are trying to wipe an entire civilisation from the face of the earth". The Telegraph.

- ^ Hitti, Philip Khuri (1957). History of Syria, including Lebanon and Palestine. Macmillan; St. Martin's P.: London, New York.

- ^ Based on interviews with community informants, this paper explores socialization for ingroup identity and endogamy among Assyrians in the United States. The Assyrians descent from the population of ancient Assyria (founded in the 24th century BC), and have lived as a linguistic, political, religious, and ethnic minority in Iraq, Iran, Syria and Turkey since the fall of the Assyrian Empire in 608 BC. Practices that maintain ethnic and cultural continuity in the Near East, the United States and elsewhere include language and residential patterns, ethnically based Christian churches characterised by unique holidays and rites, and culturally specific practices related to life-cycle events and food preparation. The interviews probe parental attitudes and practices related to ethnic identity and encouragement of endogamy. Results are being analyzed.

- ^ MacDonald, Kevin (2004-07-29). "Socialization for Ingroup Identity among Assyrians in the United States". Paper presented at a symposium on socialization for ingroup identity at the meetings of the International Society for Human Ethology, Ghent, Belgium.

- ^ Yana 2008, p. 111.

- ^ worldhistory.org

- ^ "Africiné".

- ^ Heinrichs 1993, p. 106-107.

- ^ "UNPO: Assyria". Unrepresented Nations & Peoples Organization (UNPO). 2018-01-19. Retrieved 2020-05-14.

Assyrians are one of the indigenous populations of modern-day Iraq.

- ^ a b c d Joel J. Elias (20 July 2000). "The Genetics of Modern Assyrians and their Relationship to Other People of the Middle East".

- ^ a b M.T. Akbari, Sunder S. Papiha, D.F. Roberts, and Daryoush D. Farhud. "Genetic Differentiation among Iranian Christian Communities". American Journal of Human Genetics 38 (1986): 84–98.

- ^ a b Cavalli-Sforza et al. (1994), p. 243

- ^ a b Mohammad Medhi Banoei; Morteza Hashemzadeh Chaleshtori; Mohammad Hossein Sanati; Parvin Shariati (2008). "Variation of DAT1 VNTR alleles and genotypes among old ethnic groups in Mesopotamia to the Oxus region". Human Biology. 80 (1): 73–81. doi:10.3378/1534-6617(2008)80[73:vodvaa]2.0.co;2. PMID 18505046.

- ^ a b Levon Yepiskoposian; Ashot Harutyunian & Armine Khudoyan (2006). "Genetic testing of language replacement hypothesis in southwest Asia" (PDF). Iran and the Caucasus. 10 (2): 191–208. doi:10.1163/157338406780345899. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2015-10-17. Retrieved 2021-05-10.

- ^ Joel J. Elias (2000): The Genetics of Modern Assyrians and their Relationship to Other People of the Middle East

- ^ Dinha, Nineveh (2008-11-16). "Know Your Roots". Fox 13 News. Salt Lake City. Retrieved 2020-05-14.

- ^ Nadia Al-Zahery; Maria Pala; Vincenza Battaglia; Viola Grugni; Mohammed A. Hamod; Baharak Hooshiar Kashani; Anna Olivieri; Antonio Torroni; Augusta S. Santachiara-Benerecetti; Ornella Semino (2011). "In search of the genetic footprints of Sumerians: a survey of Y-chromosome and mtDNA variation in the Marsh Arabs of Iraq". BMC Evolutionary Biology. 11: 288. doi:10.1186/1471-2148-11-288. PMC 3215667. PMID 21970613.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: unflagged free DOI (link) - ^ Dogan, Serkan; Gurkan, Cemal; Dogan, Mustafa; Balkaya, Hasan Emin; Tunc, Ramazan; Demirdov, Damla Kanliada; Ameen, Nihad Ahmed; Marjanovic, Damir (3 November 2017). "A glimpse at the intricate mosaic of ethnicities from Mesopotamia: Paternal lineages of the Northern Iraqi Arabs, Kurds, Syriacs, Turkmens and Yazidis". PLOS ONE. 12 (11): e0187408. Bibcode:2017PLoSO..1287408D. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0187408. ISSN 1932-6203. PMC 5669434. PMID 29099847.

- ^ Turoyo at Ethnologue (17th ed., 2013)

- ^ "Based on interviews with community informants, this paper explores socialization for ingroup identity and endogamy among Assyrians in the United States.

- ^ Khan 2007a, p. 110.

- ^ Khan 2007b, p. 6.

- ^ Khan 2007b, p. 5.

- ^ Joseph 2000, p. 9.

- ^ http://www.bisi.ac.uk/sites/bisi.localhost/files/languages_of_iraq.pdf

- ^ "The spread of the Aramaic language". World history. 5 June 2015. Retrieved 2019-12-29.

- ^ Bae 2004, p. 1–20.

- ^ "Intellectual Domination and the Assyrians". Nineveh Magazine, Vol. 6 No. 4 (Fourth Quarter 1983), published in Berkeley, California.

- ^ "Neo-Assyrianism & the End of the Confounded Identity". Zinda. 2006-07-06. "The fact remains that throughout the last seven years and the last 150 years for that matter the name Assyrian has always been attached to our political ambitions in the Middle East. Any time, any one of us from any of our church and tribal groups targets a political goal we present our case as Assyrians, Chaldean-Assyrians, or Syriac-Assyrians – making a connection to our "Assyrian" heritage. This is because our politics have always been Assyrian. Men like Naum Faiq and David Perley emerging from a "Syriac" or "Jacobite" background understood this as well as our Chaldean heroes, General Agha Petros d-Baz and the late Chaldean Patriarch Mar Raphael BiDawid."

- ^ "The hindrance before the advancement of the Assyrian people was not so much the attacks from without as it was from within, the doctrinal and sectarian disputes and struggles, like Monophysitism (One nature of Christ) Dyophysitism (Two natures of Christ) is a good example, these caused division, spiritually, and nationally, among the people who quarreled among themselves even to the point of shedding blood. To this very day the Assyrians are still known by various names, such as Nestorians, Jacobites, Chaldeans"

- ^ Aprim, Fred. "Dr. Freidoun Atouraya". essay. Zinda Magazine. Retrieved 2000-02-01. "AD (February 1917) Hakim Freidoun Atouraya, Rabbie Benyamin Arsanis and Dr. Baba Bet-Parhad establish the first Assyrian political party, the Assyrian Socialist Party. Two months later, Kakim Atouraya completes his "Urmia Manifesto of the United Free Assyria" which called for self-government in the regions of Urmia, Mosul, Turabdin, Nisibin, Jezira, and Julamaerk."

- ^ Farid Nazha tog vid där Naum Faiq slutade, Hujada.com

- ^ 2.^ Jump up to: a b c d e f Farid Nazha, Bethnahrin.nl

- ^ Habash, George (1999). "What do the Assyrian people want?" (PDF). Assyrian International News Agency. Retrieved 2020-05-15.

- ^ "Summary" (PDF). conference.osu.eu.

- ^ a b Hitti, Philip Khuri (1957). History of Syria, including Lebanon and Palestine. Macmillan; St. Martin's P.: London, New York.

- ^ Travis 2010, p. 237-277.

- ^ Gaunt 2015, p. 86.

- ^ Brock 1996, p. 23-35.

- ^ Coakley 2011a, p. 45.

- ^ Orlando O. Espín; James B. Nickoloff (2007). An Introductory Dictionary of Theology and Religious Studies. Liturgical Press. p. 218. ISBN 978-0-8146-5856-7.

- ^ Coakley 2011b, p. 93.

- ^ "Council of Basel-Ferrara-Florence, 1431-49 A.D.

- ^ Parpola 2004, p. 22.

- ^ Nordhoff, Sebastian; Hammarström, Harald; Forkel, Robert; Haspelmath, Martin, eds. (2013). "Northeastern Neo-Aramaic". Glottolog 2.2. Leipzig: Max Planck Institute for Evolutionary Anthropology.

Sources

- Ainsworth, William F. (1841). "An Account of a Visit to the Chaldeans, Inhabiting Central Kurdistán; And of an Ascent of the Peak of Rowándiz (Ṭúr Sheïkhíwá) in Summer in 1840". The Journal of the Royal Geographical Society of London. 11: 21–76. doi:10.2307/1797632. JSTOR 1797632.

- Ainsworth, William F. (1842a). Travels and Researches in Asia Minor, Mesopotamia, Chaldea and Armenia. Vol. 1. London: John W. Parker.

- Ainsworth, William F. (1842b). Travels and Researches in Asia Minor, Mesopotamia, Chaldea and Armenia. Vol. 2. London: John W. Parker.

- Al-Jeloo, Nicholas (1999). "Who are the Assyrians?". The Assyrian Australian Academic Journal. 4.

- Andrade, Nathanael J. (2013). Syrian Identity in the Greco-Roman World. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 9781107244566.

- Andrade, Nathanael J. (2011). "Framing the Syrian of Late Antiquity: Engagements with Hellenism". Journal of Modern Hellenism. 28 (2010-2011): 1–46.

- Andrade, Nathanael J. (2014). "Assyrians, Syrians and the Greek Language in the late Hellenistic and Roman Imperial Periods". Journal of Near Eastern Studies. 73 (2): 299–317. doi:10.1086/677249. JSTOR 10.1086/677249. S2CID 163755644.

- Andrade, Nathanael J. (2019). "Syriac and Syrians in the Later Roman Empire: Questions of Identity". The Syriac World. London: Routledge. pp. 157–174.

- Badger, George Percy (1852). The Nestorians and Their Rituals. Vol. 1. London: Joseph Masters.

- Badger, George Percy (1852). The Nestorians and Their Rituals. Vol. 2. London: Joseph Masters. ISBN 9780790544823.

- Bae, Chul-hyun (2004). "Aramaic as a Lingua Franca During the Persian Empire (538-333 B.C.E.)". Journal of Universal Language. 5: 1–20. doi:10.22425/jul.2004.5.1.1.

- Bagg, Ariel M. (2017). "Assyria and the West: Syria and the Levant". A Companion to Assyria. Hoboken: John Wiley & Sons. pp. 268–274.

- Baum, Wilhelm; Winkler, Dietmar W. (2003). The Church of the East: A Concise History. London-New York: Routledge-Curzon. ISBN 9781134430192.

- Baumer, Christoph (2006). The Church of the East: An Illustrated History of Assyrian Christianity. London-New York: Tauris. ISBN 9781845111151.

- Becker, Adam H. (2008). "The Ancient Near East in the Late Antique Near East: Syriac Christian Appropriation of the Biblical East". Antiquity in Antiquity: Jewish and Christian Pasts in the Greco-Roman World. Tübingen: Mohr Siebeck. pp. 394–415. ISBN 9783161494116.

- Becker, Adam H. (2015). Revival and Awakening: American Evangelical Missionaries in Iran and the Origins of Assyrian Nationalism. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. ISBN 9780226145310.

- Biggs, Robert D. (2005). "My Career in Assyriology and Near Eastern Archaeology" (PDF). Journal of Assyrian Academic Studies. 19 (1): 1–23. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2008-02-27.

- Brock, Sebastian P. (1996). "The 'Nestorian' Church: A Lamentable Misnomer" (PDF). Bulletin of the John Rylands Library. 78 (3): 23–35. doi:10.7227/BJRL.78.3.3.

- Butts, Aaron M. (2017). "Assyrian Christians". In Frahm, Eckart (ed.). A Companion to Assyria. Malden: John Wiley & Sons. pp. 599–612. doi:10.1002/9781118325216. ISBN 9781118325216.

- The History and Geography of Human Genes. Princeton University Press. 1994. ISBN 9780691087504.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|authors=ignored (help) - Coakley, James F. (1992). The Church of the East and the Church of England: A History of the Archbishop of Canterbury's Assyrian Mission. Oxford: Clarendon Press. ISBN 978-0-19-826744-7.

- Coakley, James F. (2011a). "Assyrians". Gorgias Encyclopedic Dictionary of the Syriac Heritage. Piscataway, NJ: Gorgias Press. p. 45.

- Coakley, James F. (2011b). "Chaldeans". Gorgias Encyclopedic Dictionary of the Syriac Heritage. Piscataway, NJ: Gorgias Press. p. 93.

- Crone, Patricia; Cook, Michael A. (1977). Hagarism: The Making of the Islamic World. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 9780521211338.

- Curtis, John (2003). "The Assyrian Heartland in the Period 612-539 BC". Continuity of Empire (?): Assyria, Media, Persia. Padova: Editrice e Libreria. pp. 157–167.

- Curtis, John (2005). "The Achaemenid Period in Northern Iraq". L'Archéologie de l'Empire Achéménide: Nouvelles Recherches. Paris: De Boccard. pp. 175–195.

- Dalley, Stephanie (1993). "Nineveh after 612 BC". Altorientalische Forschungen. 20 (1): 134–147. doi:10.1524/aofo.1993.20.1.134. S2CID 163383142.

- Dalley, Stephanie; Reyes, Andres T. (1998). "Mesopotamian Contact and Influence in the Greek World: 1. To the Persian Conquest". The Legacy of Mesopotamia. New York: Oxford University Press. pp. 85–106. ISBN 978-0-19-814946-0.

- Davies, Benjamin (1872). A Compendious and Complete Hebrew and Chaldee Lexicon to the Old Testament. London: Asher.

- Donabed, Sargon G. (2003). Remnants of Heroes: The Assyrian Experience: The Continuity of the Assyrian Heritage from Kharput to New England. Chicago: Assyrian Academic Society Press. ISBN 9780974445076.

- Donabed, Sargon G. (2012). "Rethinking Nationalism and an Appellative Conundrum: Historiography and Politics in Iraq". National Identities: Critical Inquiry into Nationhood, Politics & Culture. 14 (4): 407–431. doi:10.1080/14608944.2012.733208. S2CID 145265726.

- Donabed, Sargon G. (2015). Reforging a Forgotten History: Iraq and the Assyrians in the Twentieth Century. Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press. ISBN 9780748686056.

- Donabed, Sargon G. (2017). "Neither Syriac-speaking nor Syrian Orthodox Christians: Harput Assyrians in the United States as a Model for Ethnic Self-Categorization and Expression". Syriac in its Multi-Cultural Context. Leuven: Peeters Publishers. pp. 359–369. ISBN 9789042931640.

- Fiey, Jean Maurice (1965). "Assyriens ou Araméens?". L'Orient Syrien. 10: 141–160.

- Frazee, Charles A. (2006) [1983]. Catholics and Sultans: The Church and the Ottoman Empire 1453-1923. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 9780521027007.

- Frye, Richard N. (1992). "Assyria and Syria: Synonyms". Journal of Near Eastern Studies. 51 (4): 281–285. doi:10.1086/373570. JSTOR 545826. S2CID 161323237.

- Frye, Richard N. (1997). "Assyria and Syria: Synonyms" (PDF). Journal of Assyrian Academic Studies. 11 (2): 30–36. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2020-07-13.

- Frye, Richard N. (1999). "Reply to John Joseph" (PDF). Journal of Assyrian Academic Studies. 13 (1): 69–70. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2020-07-11.

- Frye, Richard N. (2002). "Mapping Assyria". Ideologies as Intercultural Phenomena. Milano: Università di Bologna. pp. 75–78. ISBN 9788884831071.

- Fürst, Julius (1867). A Hebrew & Chaldee Lexicon to the Old Testament: With an Introduction Giving a Short History of Hebrew Lexicography. London: Williams & Norgate.

- Gallagher, Edmon L. (2012). Hebrew Scripture in Patristic Biblical Theory: Canon, Language, Text. Leiden-Boston: Brill. ISBN 9789004228023.

- Georgis, Mariam (2017). "Nation and Identity Construction in Modern Iraq: (Re)Inserting the Assyrians". Unsettling Colonial Modernity in Islamicate Contexts. Newcastle upon Tyne: Cambridge Scholars Publishing. pp. 67–87. ISBN 9781443893749.

- Gesenius, Wilhelm; Prideaux-Tregelles, Samuel (1859). Gesenius's Hebrew and Chaldee Lexicon to the Old Testament Scriptures. London: Bagster.

- Gewargis, Odisho Malko (2002). "We Are Assyrians" (PDF). Journal of Assyrian Academic Studies. 16 (1): 77–95. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2003-04-21.

- Grant, Asahel (1841). The Nestorians, or the Lost Tribes: Containing Evidence of Their Identity. London: John Murray.

- Hanish, Shak (2015). "Assyrians". Native Peoples of the World: An Encyclopedia of Groups, Cultures and Contemporary Issues. London-New York: Routledge. p. 517. ISBN 9781317464006.

- Healey, John F. (2010). "The Church Across the Border: The Church of the East and its Chaldean Branch". Eastern Christianity in the Modern Middle East. London-New York: Routledge. pp. 41–55. ISBN 9781135193713.

- Harrak, Amir (1992). "The Ancient Name of Edessa" (PDF). Journal of Near Eastern Studies. 51 (3): 209–214. doi:10.1086/373553. S2CID 162190342. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2014-08-09.

- Harrak, Amir (2001). "Tales about Sennacherib: The Contribution of the Syriac Sources". The World of the Aramaeans. Vol. 3. Sheffield: Sheffield Academic Press. pp. 168–189. ISBN 9780567637376.

- Harrak, Amir (2005). "Ah! The Assyrian is the Rod of My Hand!: Syriac View of History after the Advent of Islam". Redefining Christian Identity: Cultural Interaction in the Middle East Since the Rise of Islam. Leuven: Peeters Publishers. pp. 45–65. ISBN 9789042914186.

- Heinrichs, Wolfhart (1993). "The Modern Assyrians - Name and Nation". Semitica: Serta philologica Constantino Tsereteli dicata. Torino: Zamorani. pp. 99–114. ISBN 9788871580241.

- Joseph, John B. (1997). "Assyria and Syria: Synonyms?" (PDF). Journal of Assyrian Academic Studies. 11 (2): 37–43. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2020-07-15.

- Joseph, John B. (1998). "The Bible and the Assyrians: It Kept their Memory Alive" (PDF). Journal of Assyrian Academic Studies. 12 (1): 70–76. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2020-07-15.

- Joseph, John B. (2000). The Modern Assyrians of the Middle East: A History of Their Encounter with Western Christian Missions, Archaeologists, and Colonial Powers. Leiden: Brill. ISBN 9004116419.

- Joseph, John B. (2003). "A Response by John Joseph". Journal of Assyrian Academic Studies. 17 (1).

- Kaufman, Stephen A. (1974). The Akkadian Influences on Aramaic. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. ISBN 9780226622811.

- Khan, Geoffrey (2007a). "Aramaic in the Medieval and Modern Periods" (PDF). Languages of Iraq: Ancient and Modern. Cambridge: The British School of Archaeology in Iraq. pp. 95–114.

- Khan, Geoffrey (2007b). "Remarks on the Historical Background of the Modern Assyrian Language". Journal of Assyrian Academic Studies. 21 (2): 4–11.

- Khan, Geoffrey (2012). "The Language of the Modern Assyrians: The North-Eastern Neo-Aramaic Dialect Group". The Assyrian Heritage: Threads of Continuity and Influence. Uppsala: Uppsala Universitet. pp. 173–199.

- Kuhrt, Amélie (1995). "The Assyrian Heartland in the Achaemenid Period". Pallas: Revue d'études antiques. 43: 239–254.

- Layard, Austen H. (1849a). Nineveh and its Remains: With an Account of a Visit to the Chaldean Christians of Kurdistan. Vol. 1. London: John Murray.

- Layard, Austen H. (1849b). Nineveh and its Remains: With an Account of a Visit to the Chaldean Christians of Kurdistan. Vol. 2. London: John Murray.

- Makko, Aryo (2010). "The Historical Roots of Contemporary Controversies: National Revival and the Assyrian Concept of Unity". Journal of Assyrian Academic Studies. 24 (1): 58–86.

- Makko, Aryo (2017). "The Assyrian Concept of Unity after Seyfo". The Assyrian Genocide: Cultural and Political Legacies. Vol. 1. London: Routledge. pp. 239–253. ISBN 9781138284050.

- Mutlu-Numansen, Sofia; Ossewaarde, Marinus (2019). "A Struggle for Genocide Recognition: How the Aramean, Assyrian, and Chaldean Diasporas Link Past and Present" (PDF). Holocaust and Genocide Studies. 33 (3): 412–428. doi:10.1093/hgs/dcz045.

- Nisan, Mordechai (2002). Minorities in the Middle East: A History of Struggle and Self-Expression (2nd ed.). Jefferson, NC: McFarland. ISBN 9780786451333.

- O’Mahony, Anthony (2006). "Syriac Christianity in the modern Middle East". The Cambridge History of Christianity: Eastern Christianity. Vol. 5. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. pp. 511–536. ISBN 9780521811132.

- Parpola, Simo (2000). "Assyrians after Assyria". Journal of the Assyrian Academic Society. 12 (2): 1–16. Archived from the original on 2008-04-26.

- Parpola, Simo (2004). "National and Ethnic Identity in the Neo-Assyrian Empire and Assyrian Identity in Post-Empire Times" (PDF). Journal of Assyrian Academic Studies. 18 (2): 5–22. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2007-11-28.

- Parpola, Simo (2014). "Mount Nisir and the Foundations of the Assyrian Church". From Source to History: Studies on Ancient Near Eastern Worlds and Beyond. Münster: Ugarit-Verlag. pp. 469–484.

- Roller, Duane W., ed. (2014). The Geography of Strabo: An English Translation, with Introduction and Notes. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 9781139952491.

- Rollinger, Robert (2006a). "Assyrios, Syrios, Syros und Leukosyros". Die Welt des Orients. 36: 72–82. JSTOR 25684050.

- Rollinger, Robert (2006b). "The Terms Assyria and Syria Again" (PDF). Journal of Near Eastern Studies. 65 (4): 283–287. doi:10.1086/511103. S2CID 162760021.

- Saggs, Henry W. F. (1984). The Might That Was Assyria. London: Sidgwick & Jackson. ISBN 9780312035112.

- Segal, Judah B. (1970). Edessa: The Blessed City. Oxford: Clarendon Press. ISBN 978-0-19-821545-5.

- Southgate, Horatio (1840). Narrative of a Tour Through Armenia, Kurdistan, Persia and Mesopotamia. Vol. 2. London: Tilt and Bogue.

- Southgate, Horatio (1842). "Report of a Visit of the Rev. H. Southgate to the Syrian Church of Mesopotamia, 1841". The Spirit of Missions. 7: 163–174, 246–251, 276–280.

- Southgate, Horatio (1844). Narrative of a Visit to the Syrian (Jacobite) Church of Mesopotamia. New York: Appleton.

- Tekoğlu, Recai; Lemaire, André; İpek, İsmet; Tosun, Kazım (2000). "La bilingue royale louvito-phénicienne de Çineköy" (PDF). Comptes rendus des séances de l'Académie des Inscriptions et Belles-Lettres. 144 (3): 961–1007.

- Thackeray, Henry St. John, ed. (1961) [1930]. Josephus: Jewish Antiquities, Books I-IV. Vol. 4. London: William Heinemann.

- Tisserant, Eugène (1931). "L'Église nestorienne". Dictionnaire de théologie catholique. Vol. 11. Paris: Letouzey et Ané. pp. 157–323.

- Travis, Hannibal (2010). Genocide in the Middle East: The Ottoman Empire, Iraq, and Sudan. Durham, NC: Carolina Academic Press. ISBN 9781594604362.

- Wigram, William Ainger (1929). The Assyrians and Their Neighbours. London: G. Bell & Sons.

- Wilmshurst, David (2000). The Ecclesiastical Organisation of the Church of the East, 1318–1913. Louvain: Peeters Publishers. ISBN 9789042908765.

- Wilmshurst, David (2011). The martyred Church: A History of the Church of the East. London: East & West Publishing Limited. ISBN 9781907318047.

- Wilmshurst, David (2019). "The Church of the East in the 'Abbasid Era". The Syriac World. London: Routledge. pp. 189–201.

- Wolk, Daniel P. (2008). "Assyrian Americans". Encyclopedia of Race, Ethnicity, and Society. Vol. 1. Los Angeles: SAGE Publications. pp. 107–109. ISBN 9781412926942.

- Woźniak, Marta (2011). "National and Social Identity Construction among the Modern Assyrians/Syrians". Parole de l'Orient. 36: 569–583.

- Woźniak, Marta (2015a). "From religious to ethno-religious: Identity change among Assyrians/Syriacs in Sweden" (Document). ECPR.

{{cite document}}: Unknown parameter|url=ignored (help); Unknown parameter|work=ignored (help) - Yana, George V. (2000). "Myth vs Reality". Journal of Assyrian Academic Studies. 14 (1): 78–82.[dead link]

- Yana, George V. (2008). Ancient and Modern Assyrians: A Scientific Analysis. Philadelphia: Exlibris Corporation. ISBN 9781465316295.

- Yildiz, Efrem (1999). "The Assyrians: A Historical and Current Reality". Journal of Assyrian Academic Studies. 13 (1): 15–30.