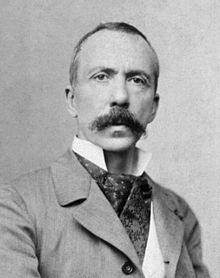

Charles Richet

Charles Richet | |

|---|---|

| |

| Born | 25 August 1850 Paris, France |

| Died | 4 December 1935 (aged 85) Paris, France |

| Alma mater | University of Paris |

| Awards | Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine (1913) |

Charles Robert Richet (25 August 1850 – 4 December 1935) was a French physiologist at the Collège de France and immunology pioneer. In 1913, he won the Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine "in recognition of his work on anaphylaxis".[1] Richet devoted many years to the study of paranormal and spiritualist phenomena, coining the term "ectoplasm". He believed in the inferiority of black people, was a proponent of eugenics, and presided over the French Eugenics Society towards the end of his life. The Richet line of professorships of medical science continued through his son Charles and his grandson Gabriel.[2] Gabriel Richet was also one of the pioneers of European nephrology.[3]

Career

[edit]

He was born on 25 August 1850 in Paris the son of Alfred Richet. He was educated at the Lycee Bonaparte in Paris then studied medicine at university in Paris.[4]

Richet spent a period of time as an intern at the Salpêtrière hospital in Paris, where he observed Jean-Martin Charcot's work with then so called "hysterical" patients.[citation needed]

In 1887, Richet became professor of physiology at the Collège de France investigating a variety of subjects such as neurochemistry, digestion, thermoregulation in homeothermic animals, and breathing.[5] In 1898, he became a member of the Académie de Médecine.[citation needed] In 1914, he became a member of the Académie des Sciences.[5]

Richet discovered the analgesic drug chloralose with Maurice Hanriot.[6]

Richet had many interests, and he wrote books about history, sociology, philosophy, psychology, as well as theatre and poetry. He was a pioneer in aviation.[5]

He was involved in the French pacifist movement. Starting in 1902, pacifist societies began to meet at a National Peace Congress, often with several hundred attendees. Unable to unify the pacifist forces they set up a small permanent delegation of French Pacifist Societies in 1902, which Richet led, together with Lucien Le Foyer as secretary-general.[7]

Discovery of anaphylaxis

[edit]Richet, working with Paul Portier, discovered the phenomenon of anaphylaxis.[8] In 1901, they joined Albert I, Prince of Monaco on a scientific expedition around the French coast of Atlantic Ocean.[9] On board Albert's ship, Princesse Alice II, they extracted a toxin (which they called a hypnotoxin) that is produced by cnidarians such as Portuguese man o' war[10] and sea anemone (Actinia sulcata).[11]

In their first experiment on the ship, they injected a dog with the toxin, expecting the dog to develop immunity (tolerance) to the toxin, but instead it suffered a severe immune reaction (hypersensitivity). In 1902, they repeated the injections in their laboratory and found that dogs normally tolerated the toxin at first injection, but when given subsequent injections three weeks later, they always developed fatal shock, regardless of the dose of the toxin they were given.[11] Thus, they discovered that the first dose, instead of inducing tolerance (prophylaxis) as they had expected, caused further doses to be deadly.[12]

In 1902, Richet coined the term aphylaxis to describe the phenomenon; he later changed it to anaphylaxis because he thought it was more euphonious.[13] The term is from the Greek ἀνά-, ana-, meaning "against", and φύλαξις, phylaxis, meaning "protection".[14] On 15 February 1902, Richet and Portier jointly presented their experiments to the Societé de Biologie in Paris.[15][16] Their research is regarded as the beginning of the scientific study of allergy (the word was coined by Clemens von Pirquet in 1906).[17] It helped explain hay fever and other allergic reactions to foreign substances, asthma, certain reactions to intoxication, and certain cases of sudden cardiac death. Richet continued to study the phenomenon of anaphylaxis, and in 1913 was awarded the Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine for his work.[18][19][1]

Parapsychology

[edit]Richet was deeply interested in the idea of extrasensory perception, and in hypnosis. In 1884, Alexandr Aksakov interested him in the medium of Eusapia Palladino.[citation needed] In 1891, Richet founded the Annales des sciences psychiques. He kept in touch with renowned occultists and spiritualists of his time such as Albert von Schrenck-Notzing, Frederic William Henry Myers and Gabriel Delanne.[citation needed] In 1919, Richet became honorary chairman of the Institut Métapsychique International in Paris, and, in 1930, its full-time president.[20]

Richet hoped to find a physical mechanism that would scientifically validate the existence of paranormal phenomena.[21] He wrote: "It has been shown that as regards subjective metapsychics the simplest and most rational explanation is to suppose the existence of a faculty of supernormal cognition ... setting in motion the human intelligence by certain vibrations that do not move the normal senses."[22] In 1905, Richet was named president of the Society for Psychical Research in the United Kingdom.[23]

In 1894, Richet coined the term ectoplasm.[24] Richet believed that some apparent mediumship could be explained physically as due to the external projection of a material substance (ectoplasm) from the body of the medium, but he didn't believe that this proposed substance had anything to do with spirits. He rejected the spirit hypothesis of mediumship as unscientific, instead supporting the sixth-sense hypothesis.[6][25] According to Richet:

It seems to me prudent not to give credence to the spiritistic hypothesis... it appears to me still (at the present time, at all events) improbable, for it contradicts (at least apparently) the most precise and definite data of physiology, whereas the hypothesis of the sixth sense is a new physiological notion which contradicts nothing that we learn from physiology. Consequently, although in certain rare cases spiritism supplies an apparently simpler explanation, I cannot bring myself to accept it. When we have fathomed the history of these unknown vibrations emanating from reality – past reality, present reality, and even future reality – we shall doubtless have given them an unwonted degree of importance. The history of the Hertzian waves shows us the ubiquity of these vibrations in the external world, imperceptible to our senses.[26]

He hypothesized a "sixth sense", an ability to perceive hypothetical vibrations, and he discussed this idea in his 1928 book Our Sixth Sense.[26] Although he believed in extrasensory perception, Richet did not believe in life after death or spirits.[6]

He investigated and studied various mediums, such as Eva Carrière, William Eglinton, Pascal Forthuny, Stefan Ossowiecki, Leonora Piper and Raphael Schermann.[6] From 1905 to 1910, Richet attended many séances led by the medium Linda Gazzera, claiming that she was a genuine medium who had performed psychokinesis, meaning that various objects had been moved in the séance room purely through the force of the mind.[6] Gazzera was exposed as a fraud in 1911.[27] Richet was also fooled into believing that Joaquin María Argamasilla, known as the "Spaniard with X-ray Eyes", had genuine psychic powers.[28] whom Harry Houdini exposed Argamasilla as a fraud in 1924.[29] According to Joseph McCabe, Richet was also duped by the fraudulent mediums Eva Carrière and Eusapia Palladino.[30]

The historian Ruth Brandon criticized Richet as credulous when it came to psychical research, pointing to "his will to believe, and his disinclination to accept any unpalatably contrary indications".[31]

Eugenics and racial beliefs

[edit]Richet was a proponent of eugenics, advocating sterilization and marriage prohibition for those with mental disabilities.[32] He expressed his eugenist ideas in his 1919 book La Sélection Humaine.[33] From 1920 to 1926 he presided over the French Eugenics Society.[34]

Psychologist Gustav Jahoda has noted that Richet "was a firm believer in the inferiority of blacks",[35] comparing black people to apes, and intellectually to imbeciles.[36]

Works

[edit]Richet's works on parapsychological subjects, which dominated his later years, include Traité de Métapsychique (Treatise on Metapsychics, 1922), Notre Sixième Sens (Our Sixth Sense, 1928), L'Avenir et la Prémonition (The Future and Premonition, 1931) and La Grande Espérance (The Great Hope, 1933).

- Maxwell, J & Richet, C. Metapsychical Phenomena: Methods and Observations (London: Duckworth, 1905).

- Richet, C. Physiologie Travaux du Laboratoire (Paris: Felix Alcan, 1909)

- Richet, C. La Sélection Humaine (Paris: Felix Alcan, 1919)

- Richet, C. Traité De Métapsychique (Paris: Felix Alcan, 1922).

- Richet, C. Thirty Years of Psychical Research (New York: The Macmillan Company, 1923).

- Richet, C. Our Sixth Sense (London: Rider, 1928).

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ a b "The Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine 1913 Charles Richet". Nobelprize.org. Retrieved 5 July 2010.

- ^ Dworetzky, Murray; Cohen, Sheldon; Cohen, Sheldon G.; Zelaya-Quesada, Myrna (August 2002). "Portier, Richet, and the discovery of anaphylaxis: A centennial". Journal of Allergy and Clinical Immunology. 110 (2): 331–336. doi:10.1016/S0091-6749(02)70118-8. PMID 12170279.

- ^ Piccoli, Giorgina Barbara; Richiero, Gilberto; Jaar, Bernard G. (13 March 2018). "The Pioneers of Nephrology – Professor Gabriel Richet: "I will maintain"". BMC Nephrology. 19 (1): 60. doi:10.1186/s12882-018-0862-0. ISSN 1471-2369. PMC 5851327. PMID 29534697.

- ^ Biographical Index of Former Fellows of the Royal Society of Edinburgh 1783–2002 (PDF). The Royal Society of Edinburgh. July 2006. ISBN 0-902-198-84-X. Archived from the original (PDF) on 4 March 2016. Retrieved 19 March 2018.

- ^ a b c Wolf, Stewart. (2012). Brain, Mind, and Medicine: Charles Richet and the Origins of Physiological Psychology. Transaction Publishers. pp. 1–101. ISBN 1-56000-063-5

- ^ a b c d e Tabori, Paul. (1972). Charles Richet. In Pioneers of the Unseen. Souvenir Press. pp. 98–132. ISBN 0-285-62042-8

- ^ Guieu, Jean-Michel (2005). "6 – Tensions nationalistes et efforts pacifistes". La France, l'Allemagne et l'Europe (1871–1945) (in French). Retrieved 11 March 2015.

- ^ Richet, Gabriel (2003). "The discovery of anaphylaxis, a brief but triumphant encounter of two physiologists (1902)". Histoire des Sciences Médicales. 37 (4): 463–469. PMID 14989211.

- ^ Dworetzky, Murray; Cohen, Sheldon; Cohen, Sheldon G.; Zelaya-Quesada, Myrna (2002). "Portier, Richet, and the discovery of anaphylaxis: A centennial". Journal of Allergy and Clinical Immunology. 110 (2): 331–336. doi:10.1016/S0091-6749(02)70118-8. PMID 12170279.

- ^ Suput, Dusan (2011). "Interactions of Cnidarian Toxins with the Immune System". Inflammation & Allergy - Drug Targets. 10 (5): 429–437. doi:10.2174/187152811797200678. PMID 21824078.

- ^ a b Boden, Stephen R.; Wesley Burks, A. (2011). "Anaphylaxis: a history with emphasis on food allergy: Anaphylaxis: a history with emphasis on food allergy". Immunological Reviews. 242 (1): 247–257. doi:10.1111/j.1600-065X.2011.01028.x. PMC 3122150. PMID 21682750.

- ^ May, Charles D. (1985). "The ancestry of allergy: Being an account of the original experimental induction of hypersensitivity recognizing the contribution of Paul Portier". Journal of Allergy and Clinical Immunology. 75 (4): 485–495. doi:10.1016/S0091-6749(85)80022-1. PMID 3884689.

- ^ Boden, SR; Wesley Burks, A (July 2011). "Anaphylaxis: a history with emphasis on food allergy". Immunological Reviews. 242 (1): 247–57. doi:10.1111/j.1600-065X.2011.01028.x. PMC 3122150. PMID 21682750., citing May CD, "The ancestry of allergy: being an account of the original experimental induction of hypersensitivity recognizing the contribution of Paul Portier", J Allergy Clin Immunol. 1985 Apr; 75(4):485–495.

- ^ "anaphylaxis". merriam-webster.com. Archived from the original on 10 April 2010. Retrieved 21 November 2009.

- ^ "De l'action anaphylactique de certains venins | Association des amis de la Bibliothèque nationale de France". sciences.amisbnf.org. Retrieved 24 June 2022.

- ^ "De l'action anaphylactique de certains venins – ScienceOpen". www.scienceopen.com. Retrieved 24 June 2022.

- ^ Ring, Johannes; Grosber, Martine; Brockow, Knut; Bergmann, Karl-Christian (2014), Bergmann, K.-C.; Ring, J. (eds.), "Anaphylaxis", Chemical Immunology and Allergy, 100, S. Karger AG: 54–61, doi:10.1159/000358503, ISBN 978-3-318-02194-3, PMID 24925384, retrieved 24 June 2022

- ^ Androutsos, G.; Karamanou, M.; Stamboulis, E.; Liappas, I.; Lykouras, E.; Papadimitriou, G. N. (2011). "The Nobel Prize laureate - father of anaphylaxis Charles-Robert Richet (1850-1935) and his anticancerous serum" (PDF). Journal of BUON. 16 (4): 783–786. PMID 22331744.

- ^ Richet, Gabriel; Estingoy, Pierrette (2003). "The life and times of Charles Richet". Histoire des Sciences Médicales. 37 (4): 501–513. ISSN 0440-8888. PMID 15025138.

- ^ "Charles Richet" Archived 11 March 2016 at the Wayback Machine. Institut Métapsychique International.

- ^ Alvarado, C. S. (2006). "Human radiations: Concepts of force in mesmerism, spiritualism and psychical research" (PDF). Journal of the Society for Psychical Research. 70: 138–162.

- ^ Richet, C. (1923). Thirty Years of Psychical Research. Translated from the second French edition. New York: Macmillan.

- ^ Berger, Arthur S; Berger, Joyce. (1995). Fear of the Unknown: Enlightened Aid-in-Dying. Praeger. p. 35. ISBN 0-275-94683-5 "In 1905, Professor Charles Richet, the French physiologist on the faculty of medicine of Paris and winner of the Nobel Prize in 1913, was made its president. Although he was a materialist and positivist, he was drawn to psychical research."

- ^ Blom, Jan Dirk. (2010). A Dictionary of Hallucinations. Springer. p. 168. ISBN 978-1-4419-1222-0

- ^ Ashby, Robert H. (1972). The Guidebook for the Study of Psychical Research. Rider. pp. 162–179

- ^ a b Richet, Charles. (nd, ca 1928). Our Sixth Sense. London: Rider. (First published in French, 1928)

- ^ McCabe, Joseph. (1920). Is Spiritualism Based On Fraud? The Evidence Given By Sir A. C. Doyle and Others Drastically Examined. London Watts & Co. pp. 33–34

- ^ Polidoro, Massimo. (2001). Final Séance: The Strange Friendship Between Houdini and Conan Doyle. Prometheus Books. pp. 171–172. ISBN 978-1591020868

- ^ Nickell, Joe. (2007). Adventures in Paranormal Investigation. The University Press of Kentucky. p. 215. ISBN 978-0813124674

- ^ McCabe, Joseph. (1920). Scientific Men and Spiritualism: A Skeptic's Analysis. The Living Age. 12 June. pp. 652–657.

- ^ Brandon, Ruth. (1983). The Spiritualists: The Passion for the Occult in the Nineteenth and Twentieth Centuries. Weidenfeld and Nicolson. p. 135

- ^ Cassata, Francesco. (2011). Building the New Man: Eugenics, Racial Sciences and Genetics in Twentieth-Century Italy. Central European University Press. p. 73. ISBN 978-963-9776-83-8

- ^ Mazliak, Laurent; Tazzioli, Rossana. (2009). Mathematicians at War: Volterra and His French Colleagues in World War I. Springer. p. 42. ISBN 978-90-481-2739-9

- ^ MacKellar, Calum; Bechtel, Christopher. (2014). The Ethics of the New Eugenics. Berghahn Books. pp. 18–19. ISBN 978-1-78238-120-4

- ^ Gustav Jahoda. (1999). Images of Savages: Ancient Roots of Modern Prejudice in Western Culture. Routledge. p. 154. ISBN 978-0-415-18855-5

- ^ Bain, Paul G; Vaes, Jeroen; Leyens, Jacques Philippe. (2014). Humanness and Dehumanization. Routledge. p. 28. ISBN 978-1-84872-610-9

Further reading

[edit]- M. Brady Brower. (2010). Unruly Spirits: The Science of Psychic Phenomena in Modern France. University of Illinois Press. ISBN 978-0-252-03564-7

- Sofie Lachapelle. (2011). Investigating the Supernatural: From Spiritism and Occultism to Psychical Research and Metapsychics in France, 1853–1931. Johns Hopkins University Press. ISBN 978-1-4214-0013-6

- Paul Tabori. (1972). Pioneers of the Unseen. Souvenir Press. ISBN 0-285-62042-8

- Stewart Wolf. (2012). Brain, Mind, and Medicine: Charles Richet and the Origins of Physiological Psychology. Transaction Publishers. ISBN 1-56000-063-5

External links

[edit]- Works by Charles Richet at Project Gutenberg

- Works by or about Charles Richet at the Internet Archive

- Short biography and bibliography in the Virtual Laboratory of the Max Planck Institute for the History of Science

- Richet's Dictionnaire de physiologie (1895–1928) as fullscan from the original

- "Charles Robert Richet photo". Archived from the original on 27 October 2009. Retrieved 8 October 2010.

- Charles Richet on Nobelprize.org including the Nobel Lecture on 11 December 1913 Anaphylaxis

- Short biography by Nandor Fodor on SurvivalAfterDeath.org.uk with links to several articles on psychical research

- 1850 births

- 1935 deaths

- Physicians from Paris

- French physiologists

- French immunologists

- Nobel laureates in Physiology or Medicine

- French Nobel laureates

- Corresponding members of the Saint Petersburg Academy of Sciences

- French hypnotists

- French occultists

- Members of the French Academy of Sciences

- French writers on paranormal topics

- French parapsychologists

- White supremacists

- Grand Officers of the Legion of Honour