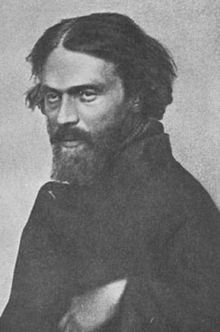

Cyprian Norwid

Cyprian Norwid | |

|---|---|

| |

| Born | Cyprian Konstanty Norwid 24 September 1821 Laskowo-Głuchy near Warsaw, Congress Poland |

| Died | 23 May 1883 (aged 61) Paris, France |

| Occupation | Poet, Essayist |

| Language | Polish |

| Nationality | Polish |

| Genre | Romanticism, Parnassism |

| Notable works | Vade-mecum Promethidion Czarne kwiaty. Białe kwiaty |

Cyprian Kamil Norwid, a.k.a. Cyprian Konstanty Norwid (Polish pronunciation: [ˈt͡sɨprjan ˈnɔrvid]; 24 September 1821 – 23 May 1883) was a nationally esteemed Polish poet, dramatist, painter, and sculptor. He was born in the Masovian village of Laskowo-Głuchy near Warsaw. One of his maternal ancestors was the Polish King John III Sobieski.[1]

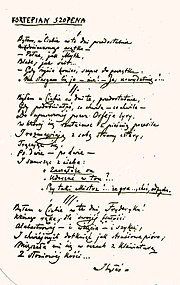

Norwid is regarded as one of the second generation of romantics. He wrote many well-known poems including Fortepian Szopena ("Chopin's Piano"), Moja piosnka [II] ("My Song [II]") and Bema pamięci żałobny-rapsod ("A Funeral Rhapsody in Memory of General Bem"). Norwid led a tragic and often poverty-stricken life (once he had to live in a cemetery crypt). He experienced increasing health problems, unrequited love, harsh critical reviews, and increasing social isolation. He lived abroad most of his life, especially in London and in Paris, where he died.

Norwid's original and non-conformist style was not appreciated in his lifetime and partially due to this fact, he was excluded from high society. His work was only rediscovered and appreciated during the Young Poland art period of the late nineteenth and early twentieth century. He is now considered one of the four most important Polish Romantic poets. Other literary historians, however, consider this an oversimplification, and regard his style to be more characteristic of classicism and parnassianism.

Life

Born into the Topór coat of arms, Cyprian Norwid and his brother Ludwik were early orphaned. For most of their childhoods, they were educated at Warsaw schools. In 1830 Norwid interrupted his schooling (not having completed the fifth grade) and entered a private school of painting. His incomplete formal education forced him to become an autodidact.

His first foray into the literary sphere occurred in the periodical Piśmiennictwo Krajowe, which published his first poem, "Mój ostatni sonet" ("My Last Sonnet"), in issue 8, 1840.

Europe

In 1842 Norwid went to Dresden, ostensibly to gain instruction in sculpture. He later also visited Venice and Florence. After he settled in Rome in 1844, his fiancée Kamila broke off their engagement. Later he met Maria Kalergis, née Nesselrode, who became his "lost love", even as his health deteriorated.

The poet also traveled to Berlin, where he participated in university lectures and meetings with local Polonia. It was a time for Norwid where he made many social, artistic and political acquaintances. After being arrested and forced to leave Prussia in 1846, Norwid went to Brussels. During the European Revolutions of 1848, he stayed in Rome, where he met fellow Polish intellectuals Adam Mickiewicz and Zygmunt Krasiński.

During 1849–1852, Norwid resided in Paris, where he met fellow Poles Frédéric Chopin and Juliusz Słowacki, as well as Russians Ivan Turgenev and Alexander Herzen. Financial hardship, unrequited love, political misunderstandings, and negative critical reception of his works put Norwid in a dire situation at this stage. Norwid lived in poverty and suffered from progressive blindness and deafness, but he still managed to publish his work in the Parisian publication Goniec polski.

U.S.A.

Under the protection of Władysław Zamoyski, Norwid decided to emigrate to the United States of America on 29 September 1852. He arrived aboard the Margaret Evans in New York City on 12 February 1853, and during the spring, obtained a well-paying job at a graphics firm. By autumn, he had learned about the outbreak of the Crimean War. This made him consider a return to Europe, and he wrote to Mickiewicz and Herzen, requesting their assistance.

Paris

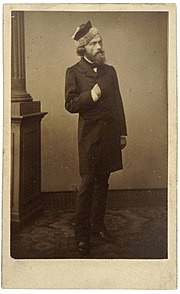

Pantaleon Szyndler

During April 1854, Norwid returned to Europe with Prince Marcel Lubomirski. He lived in London and earned enough money through artistic endeavours to be finally able to return to Paris. With his artistic work revived, Norwid was able to publish several works. Norwid took a very keen interest in the outbreak of the January Uprising in 1863. Although he could not participate personally due to his poor health, Norwid hoped to personally influence the outcome of the event.

In 1866, the poet finished his work on Vade-Mecum, a vast anthology of verse. However, despite his greatest efforts and formidable contacts, it was unable to be published. This included Prince Władysław Czartoryski failing to grant the poet the loan he had promised.

In subsequent years, Norwid lived in extreme poverty and suffered from tuberculosis. His cousin, Michał Kleczkowski, later relocated Norwid to the nursing home of St. Casimir's Institute, on the outskirts of Paris. During the last months of his life, Norwid was weak and bed-ridden; he frequently wept and refused to speak with anyone. He died in the morning of 23 May 1883.

Legacy

Literary historians view Norwid's work as being too far ahead of its time to be appreciated,[2] possessing elements of romanticism, classicism and parnassianism. Following his death, many of Norwid's works were forgotten; it was not until the Young Poland period that his finesse and style was appreciated. At that time, his work was discovered and popularised by Zenon Przesmycki, a Polish poet and literary critic who was a member of the Polish Academy of Literature. Some eventually concluded that during his life, Norwid had been rejected by his contemporaries so that he could be understood by the next generation of "late grandsons."[3]

Esoteric opinion is divided however, as to whether he was a true Romanticist artist – or if he was artistically ahead of his time. Norwid's "Collected Works" (Dzieła Zebrane) were published in 1968 by Juliusz Wiktor Gomulicki, a Norwid biographer and commentator. The full iconic collection of the artist's work was released during the period 1971–76 as Pisma Wszystkie ("Writings of All"). Comprising 11 volumes, it includes all of Norwid's poetry as well as his letters and reproductions of his artwork.

On 24 September 2001, 118 years after his death in France, an urn containing soil from the collective grave where Norwid had been buried, from the Paris cemetery of Montmorency, was enshrined in the "Crypts of the Bards" at Wawel Cathedral. There, Norwid's remains were placed next to those of fellow Polish poets Adam Mickiewicz and Juliusz Slowacki.

The cathedral's Zygmunt Bell, heard only when events of great national and religious significance occur, resounded loudly to mark the poet's return to his homeland. During a special Thanksgiving Mass held at the cathedral, the Archbishop of Kraków, a cardinal Franciszek Macharski said that 74 years after the remains of Juliusz Slowacki were brought in, again the doors of the crypt of bards have opened "to receive the great poet, Cyprian Norwid, into Wawel's royal cathedral, for he was the equal of kings".[4]

In 1966, the Polish Scouts in Chicago acquired a 240-acre parcel of property in the northwoods of Wisconsin, 20 miles west of Crivitz, Wisconsin and named it Camp Norwid in his honor. The camp is private property, and has been a forging place for generations of youth of Polish heritage from the Chicago and Milwaukee areas, and across the United States.

Works

Norwid's most prodigious work, Vade-mecum, written between 1858 and 1865, was first published a century after his death. Some of Norwid's works have been translated into English by the American academic Walter Whipple.

- Template:En icon The Larva

- Template:En icon Mother Tongue (Język ojczysty)

- Template:En icon My Song

- Template:En icon To Citizen John Brown (Do obywatela Johna Brown)

- Template:En icon What Did You Do to Athens, Socrates? (Coś ty Atenom zrobił Sokratesie...)

- Template:Pl icon Fortepian Szopena

- Template:Pl icon Assunta (1870)

- Template:Pl icon Vade-Mecum

- Template:Bn icon Poems of Cyprian Norwid (কামিল নরভিদের কবিতা)

The entries above that are accompanied by the Template:En icon icon have been translated into English by Whipple and the Template:Bn icon icon marked book translated into Bengali language by Annonto Uzzul.[5]

See also

Notes

- ^ Marcin Król, Konserwatyści a niepodległość, Warszawa 1985, p. 160.

- ^ Hans Robert Jauss: Preface to the German translation of Vade Mecum, München: Fink, 1981

- ^ Wilson, Joshua (30 May 2012). "Flames of Goodness". The New Republic. Retrieved 30 May 2012.

- ^ Cyprian Nowid's remains symbolically repatriated – 2001, available at: http://info-poland.buffalo.edu/web/arts_culture/literature/poetry/norwid/rest.shtml

- ^ http://www.eobserverbd.com/share.php?q=2015%2F02%2F24%2F17%2Fdetails%2F17_r4_c1.jpg&d=2015%2F02%2F24%2F

References

- Adamiec, Dr. Mark Cyprian Norwid

- Speech made by Pope John Paul II to the representatives of the Institute of Polish National Patrimony

- Biography links

- Norwid laid to rest in Wawel Cathedral

- Repository of translated poems

- Maria Kalergis, Listy do Adama Potockiego (Letters to Adam Potocki), edited by Halina Kenarowa, translated from the French by Halina Kenarowa and Róża Drojecka, Warsaw, 1986.

External links

- Profile of Cyprian Norwid at Culture.pl

- Works by or about Cyprian Norwid at the Internet Archive

- Works by Cyprian Norwid at LibriVox (public domain audiobooks)

- 1821 births

- 1883 deaths

- People from Wyszków County

- 19th-century Polish painters

- Polish poets

- Polish sculptors

- Polish dramatists and playwrights

- Male dramatists and playwrights

- Polish Roman Catholics

- Roman Catholic writers

- Activists of the Great Emigration

- 19th-century sculptors

- 19th-century poets

- 19th-century Polish dramatists and playwrights

- Polish male poets

- 19th-century male writers