Discovery Program

NASA's Discovery Program is a series of lower-cost (as compared to New Frontiers or Flagship Programs), highly focused American scientific space missions that are exploring the Solar System. It was founded in 1992 to implement then-NASA Administrator Daniel S. Goldin's vision of "faster, better, cheaper" planetary missions. Discovery missions differ from traditional NASA missions where targets and objectives are pre-specified. Instead, these cost-capped missions are proposed and led by a scientist called the Principal Investigator (PI). Proposing teams may include people from industry, small businesses, government laboratories, and universities. Proposals are selected through a competitive peer review process. All of the completed Discovery missions are accomplishing ground-breaking science and adding significantly to the body of knowledge about the Solar System.

NASA also accepts proposals for competitively selected Discovery Program Missions of Opportunity. This provides opportunities to participate in non-NASA missions by providing funding for a science instrument or hardware components of a science instrument or to re-purpose an existing NASA spacecraft. These opportunities are currently offered through NASA's Stand Alone Mission of Opportunity program.

On January 4, 2017 NASA announced that the next Discovery mission selection included the double-selection of ''Lucy'', to visit several asteroids and Trojans, and ''Psyche'', to visit the metal asteroid Psyche, as the thirteenth and fourteenth Discovery missions, respectively.[2]

History

In 1989, the Solar System Exploration Division (SSED) at NASA Headquarters initiated a series of workshops to define a new strategy for exploration through the year 2000. The panels included a Small Mission Program Group (SMPG) that was chartered to devise a rationale for missions that would be low cost and allow focused scientific questions to be addressed in a relatively short time.[3] A fast-paced study for a potential mission was requested and funding arrangements were made in 1990. The new program was called 'Discovery' and the panel assessed a number of concepts that could be implemented as low-cost programs, with 'Near Earth Asteroid Rendezvous' (NEAR) as the first mission to be implemented.[3]

On February 17, 1996, NEAR became the first mission to launch in the Discovery Program.[3] The Mars Pathfinder launched on December 4, 1996, demonstrated a number of innovative, economical, and highly effective approaches to spacecraft and planetary mission design such as the inflated airbags that allowed the Sojourner rover to endure the landing.[3] Note that the two Mars Exploration Rovers, Opportunity and Spirit, were not a part of the Discovery Program, although they did re-use the overall landing system of Mars Pathfinder. Also, Phoenix and MAVEN were in the Mars Scout Program and not the Discovery Program.

Mission timeline

Missions

Standalone missions

| № | Name | Targets | Launch date | Rocket | Launch mass | First science | Status | Principal investigator | Cost million USD |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | NEAR Shoemaker | 433 Eros (lander), 253 Mathilde | February 17, 1996 | Delta II 7925-8 |

800 kg (1,800 lb) |

June 1997 | Completed in 2001 | Andrew Cheng (APL)[4] |

224 (2000)[5] |

| Near Earth Asteroid Rendezvous – Shoemaker (named after Eugene Shoemaker) performed a flyby of 253 Mathilde on 27 June 1997, and an Earth flyby in 1998. It flew by 433 Eros once in 1998, before a second approach allowed it to enter orbit around Eros of February 14, 2000. After a year of orbital observations, the spacecraft was landed on the asteroid on February 2001, and surprisingly continued to function successfully touched down softly at under 2 m/s, becoming the first probe to soft-land on an asteroid. The probe continued to emit signals until February 28, 2001, and the final attempt to communicate with the spacecraft was on December 10, 2002. | |||||||||

| 2 | Mars Pathfinder | Mars (rover) | December 4, 1996 | Delta II 7925 |

264 kg (582 lb) |

July 4, 1997 | Completed in 1998 | Joseph Boyce (JPL) |

265 (1998)[6] |

| It was launched a month after the Mars Global Surveyor. After entering the Martian atmosphere, the hypersonic capsule deployed complex landing system including a parachute and an airbag to hit the surface at 14 m/s. The lander deployed Sojourner rover (10.5 kg) on the surface on July 4, 1997 on Mars's Ares Vallis thus becoming the first rover to operate outside the Earth-Moon system. It carried a series of scientific instruments to analyze the Martian atmosphere, climate, geology and the composition of its rocks and soil. It completed its primary and extended mission and after over 80 days, the last signal was sent on September 27, 1997. Mission was terminated on March 10, 1998. | |||||||||

| 3 | Lunar Prospector | Moon | January 7, 1998 | Athena II [Star-3700S] |

296 kg (653 lb) |

January 16, 1998 | Completed in 1999 | Alan Binder (LRI)[7] |

63 (1998)[8] |

| A Moon orbiter to characterize the lunar mineralogy, including polar ice deposits, measurements of magnetic and gravity fields, and study of lunar outgassing events. After preliminary mappings, it achieved the targeted primary Lunar orbit on January 16. Primary mission in this orbit lasted one year until January 28, 1999, followed up by a half-year extended mission in a lower orbit for higher resolution. On July 31, 1999 it deliberately impacted into the Shoemaker crater near the Lunar South pole in hope to produce water vapor plumes that would be observable from Earth.[9][10][7] | |||||||||

| 4 | Stardust | 81P/Wild (sample collect), 5535 Annefrank, Tempel 1 | February 7, 1999 | Delta II 7426-9.5 |

391 kg (862 lb) |

November 2, 2002 | Completed in 2011 | Donald Brownlee (UW) |

200 (2011)[11] |

| Mission to collect interstellar dust and dust particles from the nucleus of comet 81P/Wild for study on Earth. After a flyby of Earth and then of asteroid 5535 Annefrank in November 2002. After a flyby of comet Wild 2 in January 2004, during which the Sample Collection plate collected dust grain samples from the coma. Later, it separated from its sample-return capsule, which returned to Earth on January 15, 2006. This capsule is on display at the National Air and Space Museum in Washington D.C. Scientists worldwide are studying the comet dust samples while citizen scientists are finding interstellar dust bits through the Stardust@home project, and in 2014, scientists announced the identification of possible interstellar dust particles. Meanwhile, the spacecraft averted reentry, and was diverted for a flyby of Tempel 1 comet, as part of Stardust-NExT extension, to observe the crater left by Deep Impact. 'Stardust did a final burn to deplete its remaining fuel on March 24, 2011.[12] | |||||||||

| 5 | Genesis | Solar wind (collect at Sun–Earth L1) | August 8, 2001 | Delta II 7326 |

494 kg (1,089 lb)(dry) |

December 3, 2001 | Completed in 2004 | Donald Burnett (Caltech)[13] |

209M (2004)[13] |

| Mission to collect solar wind charged particles for analysis on Earth. After reaching L1 orbit on November 16, 2001, it collected solar wind for 850 days between 2001–2004. It left Lissajous orbit and began its return to Earth on April 22, 2004, but on September 8, 2004, the sample-return capsule's parachute failed to deploy, and the capsule crashed into the Utah desert. However, solar wind samples were salvaged and are available for study. Despite the hard landing, Genesis has met or anticipates meeting all its baseline science objectives. | |||||||||

| 6 | CONTOUR | Encke, Schwassmann-Wachmann-3 | July 3, 2002 | Delta II 7425 [Star-30BP] |

398 kg (877 lb) |

— | Disintegrated after launch |

Joseph Veverka (Cornell)[14] |

154 (1997)[15] |

| Comet Nucleus Tour was a failed mission to visit and study comets. On August 15, 2002, after a planned maneuver that was intended to propel it out of Earth orbit and into its comet-chasing solar orbit, the spacecraft was lost. The investigation board concluded the probable cause was structural failure of the spacecraft due to plume heating during the Star-30 solid-rocket motor burn.[3][16] Subsequent investigation revealed that it broke into at least three pieces, the cause likely being structural failure during the rocket motor burn that was to push it from Earth orbit into a solar orbit. | |||||||||

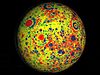

| 7 | MESSENGER | Mercury, Venus | August 3, 2004 | Delta II 7925H-9.5 |

1,108 kg (2,443 lb) |

August 2005 | Completed in 2015 | Sean Solomon (APL)[17] |

450 (2015)[18] |

| Mercury Surface, Space Environment, Geochemistry and Ranging conducted the first orbital study of Mercury. Its science goals were to provide the first images of the entire planet and collect detailed information on the composition and structure of Mercury's crust, its geologic history, the nature of its thin atmosphere and active magnetosphere, and the makeup of its core and polar materials. It was only the second spacecraft to flyby Mercury, after Mariner 10 in 1975. After one Earth flyby, two of Venus and three of Mercury, it finally entered orbit around Mercury on March 18, 2011. The primary science mission began on April 4, 2011 and lasted until March 17, 2012. It achieved 100% mapping of Mercury on March 6, 2013, and completed its first year-long extended mission on March 17, 2013. After two extension missions, the spacecraft ran out of propellant and was deorbited on April 30, 2015.[19][17] | |||||||||

| 8 | Deep Impact | Tempel 1 (impactor), 103P/Hartley | January 12, 2005 | Delta II 7925 |

650 kg (1,430 lb) |

April 25, 2005 | Completed in 2013 | Michael A'Hearn (UMD)[20] |

330 (2005)[21] |

| The spacecraft released a 350 kg impactor into the path of comet Tempel 1 on July 3, 2005. The impact occurred on July 4, 2005 releasing an energy equivalent of 4.7 tons of TNT. Plume of the impact were observed with several space-based observatories. The 2007 Stardust spacecraft NExT mission determined the resulting crater's diameter to be 150 meters (490 ft). After the successful completion of its mission, it was put in hibernation and then reactivated for a new mission designated EPOXI. On November 4, 2010 it performed a flyby of comet Hartley 2.[20] In 2012 it performed long-distance observations of comet Garradd C/2009 P1, and in 2013 of Comet ISON. Contact was lost in August 2013, later attributed to a Y2K-like error. | |||||||||

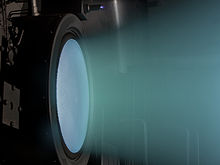

| 9 | Dawn | 4 Vesta, Ceres | September 27, 2007 | Delta II 7925H |

1,218 kg (2,685 lb) |

May 3, 2011 | Operational until 2018 | Christopher T. Russell (UCLA)[22] | 472 (2015)[23] |

| Dawn is the first spacecraft to orbit two extraterrestrial bodies, the two most massive objects of the asteroid belt: the protoplanet Vesta and the dwarf planet Ceres. This was made possible by employing highly efficient solar electric ion thrusters, with just 425 kg of xenon for the entire mission after escaping Earth. After a 2009 Mars flyby, it entered orbit around Vesta on July 16, 2011. It entered its lowest Vesta orbit on December 8, 2011, and after a year-long Vesta mission, it left its orbit on September 5, 2012. It entered Ceres' orbit on March 6, 2015 thus becoming the first spacecraft to visit a dwarf planet. It began its lowest orbit on December 16, 2015, and in June 2016 it was approved for an extended mission.[24][25] On October 19, 2017, NASA announced that the mission would be extended until its hydrazine fuel runs out, possibly in the second half of 2018. | |||||||||

| 10 | Kepler | transiting exoplanet survey | March 7, 2009 | Delta II 7925-10L |

1,052 kg (2,319 lb) |

May 12, 2009 | Operational until 2019 | William Borucki (NASA Ames) |

640 (2009)[26] |

| A space observatory named after Johannes Kepler in an heliocentric, Earth-trailing orbit tasked to explore the structure and diversity of exoplanet systems, with a special emphasis on the detection of Earth-size planets in orbit around stars outside our Solar System.[27] It announced its first exoplanet discoveries in January 2010. Initially planned for 3.5 years, it is still functional after 9 years, including a K2 "Second Light" extension mission. By 2015, the spacecraft had detected over 2,300 confirmed planets,[28][29] including hot Jupiters, super-Earths, circumbinary planets, and planets located in the circumstellar habitable zones of their host stars. In addition, Kepler has detected over 3,600 unconfirmed planet candidates[30][31] and over 2,000 eclipsing binary stars.[31] | |||||||||

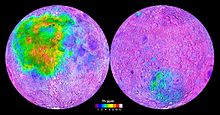

| 11 | GRAIL | Moon | September 10, 2011 | Delta II 7920H-10C |

307 kg (677 lb) |

Mar 7, 2012 | Completed in 2012 | Maria Zuber (MIT) |

496 (2011)[32] |

| Gravity Recovery and Interior Laboratory provided higher-quality gravitational field mapping of the Moon to determine its interior structure.[33] The two small spacecrafts GRAIL A (Ebb) and GRAIL B (Flow) separated soon after the launch and entered Lunar orbits on December 31, 2011 and January 1, 2012, respectively. The primary scientific phase was achieved in May 2012. After the extended mission phase, the two spacecrafts impacted the Moon on December 17, 2012. MoonKAM (Moon Knowledge Acquired by Middle school students) was an education related sub-program and instrument of this mission.[34] | |||||||||

| 12 | InSight | Mars (lander) | May 5, 2018 | Atlas V (401) |

721 kg (1,590 lb) |

November 2018 | En route to Mars | W. Bruce Banerdt (JPL) |

830 (2016)[35] |

| Interior Exploration using Seismic Investigations, Geodesy and Heat Transport is a 358 kg lander reusing technology from the Mars Phoenix lander. It is intended to study the interior structure and composition of Mars and advance understanding of the formation and evolution of terrestrial planets.[36] Its launch was delayed from 2016 to May 2018.[37] The landing is planned for November 2018 at a site about 600 km (370 mi) from the Curiosity rover. | |||||||||

| 13 | Lucy | Jupiter trojans | October 2021 | TBA | 2025 | In development | Harold F. Levison (SwRI) |

450 + launch[38] | |

| Named after the hominin Lucy, it will tour six Trojan asteroids in order to better understand the formation and evolution of the Solar System.[39] The launch is planned for 2021.[40] It will arrive at Jupiter's L4 Trojan cloud in 2027 to visit 3548 Eurybates, 15094 Polymele, 11351 Leucus, and 21900 Orus. After an Earth flyby, Lucy will arrive at the L5 Trojan cloud (trails behind Jupiter) to visit the 617 Patroclus−Menoetius binary in 2033. It will also fly by the inner main-belt asteroid 52246 Donaldjohanson in 2025. | |||||||||

| 14 | Psyche | 16 Psyche | 2022 | TBA | 2026 | In development | Lindy Elkins-Tanton (ASU) |

450 + launch[38] | |

| Psyche orbiter will travel to and study the asteroid 16 Psyche, the most massive metallic asteroid in the asteroid belt, thought to be the exposed iron core of a protoplanet.[41] The launch is planned for 2022.[42] It will carry an imager, a magnetometer, and a gamma-ray spectrometer. | |||||||||

Missions of opportunity

This provides opportunities to participate in non-NASA missions by providing funding for a science instrument or hardware components of a science instrument, or specific extended mission for spacecraft that may different from its original purpose. Some examples include: M3, EPOXI, EPOCH, DIXI, and NEXT.

- Moon Mineralogy Mapper is a NASA-designed instrument placed on board the ISRO's Chandrayaan orbiter. Launched in 2008, it was designed to explore the Moon's mineral composition at high resolution. M3’s detection of water on the Moon was announced in Sept. 2009, one month after the mission ended. The Principal Investigator was Carle Pieters of Brown University.

- Extrasolar Planet Observation and Deep Impact Extended Investigation (EPOXI) was selected in 2007.[43] It was a series of two new missions for the existing Deep Impact probe following its success at Tempel 1:

- The Extrasolar Planet Observations and Characterization (EPOCh) mission used the Deep Impact high-resolution camera in 2008 to better characterize known giant extrasolar planets orbiting other stars and to search for additional planets in the same system. The Principal Investigator was L. Drake Deming of NASA's Goddard Space Flight Center.

- The Deep Impact eXtended Investigation of Comets (DIXI) mission used the Deep Impact mission's spacecraft for a flyby mission to a second comet, Hartley 2. The goal was to take pictures of its nucleus to increase our understanding of the diversity of comets. The flyby of Hartley 2 was successful with closest approach occurring on November 4, 2010. Michael A'Hearn of the University of Maryland was the Principal Investigator.

- New Exploration of Tempel 1 (NExT) was a new mission for the Stardust spacecraft to fly by comet Tempel 1 in 2011 and observe changes since the Deep Impact mission visited it in July 2005. Later in 2005, Tempel 1 made its closest approach to the Sun, possibly changing the surface of the comet. The flyby was completed successfully on February 15, 2011. Joseph Veverka of Cornell University is the Principal Investigator.

- ASPERA-3, an instrument designed to study the interaction between the solar wind and the atmosphere of Mars, is flying on board the European Space Agency's Mars Express orbiter. Launched in June 2003, it has been orbiting Mars since Dec. 2003. The Principal Investigator is David Winningham of Southwest Research Institute.

- Strofio[44] is a unique mass spectrometer that is part of the SERENA instrument package that will fly on board the European Space Agency's BepiColombo/Mercury Planetary Orbiter spacecraft. Strofio will study the atoms and molecules that compose Mercury's atmosphere to reveal the composition of the planet's surface. Stefano Livi of Southwest Research Institute is the Principal Investigator.

Proposals

However often the funding comes in, there is a selection process with perhaps two dozen concepts. These sometimes get further matured and re-proposed in another selection or program.[45] An example of this is Suess-Urey Mission, which was passed over in favor of the successful Stardust mission, but was eventually flown as Genesis,[45] while a more extensive mission similar to INSIDE was flown as Juno in the New Frontiers program. Some of these concepts went on to become actual missions, or similar concepts were eventually realized in another mission class. This list is a mix of previous and current proposals.

Additional examples of Discovery-class mission proposals include:

- Whipple, space-observatory to detect Oort cloud by transit method

- Io Volcano Observer

- Comet Hopper (CHopper)

- Titan Mare Explorer (TiME)

- Suess-Urey, similar to the later Genesis mission.[45]

- Hermes, a Mercury orbiter.[46] (compare to MESSENGER Mercury orbiter)

- INSIDE Jupiter, an orbiter that would map Jupiter's magnetic and gravity fields in an effort to study the giant planet's interior structure.[47] The concept was further matured and implemented as Juno in the New Frontiers program.[48]

- The Dust Telescope is a space observatory that would measure various properties of incoming cosmic dust.[49] The dust telescope would combine a trajectory sensor and a mass spectrometer, to allow the elemental and even isotopic composition to be analyzed.[49]

- OSIRIS (Origins Spectral Interpretation, Resource Identification and Security) was an asteroid observation and sample return mission concept selected in 2006 for further concept studies.[50] It was further matured and launched September 8, 2016 as OSIRIS-REx in the New Frontiers Program.[51]

- Hera is a mission concept for near-Earth asteroid sample return.[52] Envisioned as the follow-on from the NEAR mission, the design was intended to collect three samples from three different asteroids.[53] The initial proposal proposed 1999-AO10, 2000-AG6 and 1998-UQ asteroids, but this was later expanded to three of 40 different options.[53]

- Small Body Grand Tour, an asteroid rendezvous mission.[54] This 1993 concept reviews possible targets for what became NEAR— 4660 Nereus and 2019 Van Albada.[54] Other targets considered for an extended mission included Encke's comet (2P), 433 Eros, 1036 Ganymed, 4 Vesta, and 4015 Wilson–Harrington (1979 VA).[54] (NEAR did visit 433 Eros and Dawn visited 4 Vesta)

- Comet Coma Rendezvous Sample Return, a spacecraft designed to rendezvous with a comet, make extended observations within the cometary coma (but not land on the comet), gently collect multiple coma samples, and return them to Earth for study.[55] (See also Stardust (spacecraft))

- Micro Exo Explorer would use a new form of micro-electric propulsion, called 'Micro Electro-fluidic-spray Propulsion' to travel to a near Earth object and gather important data.[56]

- Mars focused

- Pascal, a Mars climate network mission.[57]

- MUADEE (Mars Upper Atmosphere Dynamics, Energetics, and Evolution)[58] (compare to MAVEN of the Mars Scout program)

- Phobos Surveyor is an orbiter mission concept to the Mars moon Phobos, which would also deploy special rovers for the moon's low gravity environment.

- PCROSS, based on LCROSS but to Mars' moon Phobos.[59]

- Merlin mission would place a lander on Mars' moon Deimos.[60]

- Mars Moons Multiple Landings Mission (M4), would conduct multiple landings on Phobos and Deimos.[61]

- Hall is a Phobos and Deimos sample return mission.[62]

- Aladdin was a Discovery-class Phobos and Deimos sample return mission.[63] It was a finalist in the 1999 Discovery selection, with a planned launch in 2001 and return of the samples by 2006.[64] Sample collection was intended to work by sending projectiles into the moons, then collecting the ejecta by means of a collector spacecraft flyby.[64]

- Mars Geyser Hopper is a lander that would investigate the springtime carbon dioxide Martian geysers found in regions around the south pole of Mars.[65][66]

- MAGIC (Mars Geoscience Imaging at Centimeter-scale) is an orbiter that would provide images of the Martian surface at 5–10 cm/pixel, permitting resolution of features as small as 20–40 cm.[67]

- Red Dragon, a Mars lander and sample return.[68]

- Lunar focused

- Lunar sample return from the South Pole–Aitken basin. No geologic model adequately accounts for all of the characteristics of the area and disagreements are fundamental.[69]

- EXOMOON, in situ investigation on Earth's Moon.[70]

- PSOLHO, would use the Moon as an occulter to look for exoplanets.[71]

- Lunette, a lunar lander.[72]

- Twin Lunar Lander, a geophysics mission to the Moon.[73]

- Venus focused

- Venus Multiprobe, proposed for a 1999 launch, would have dropped 16 atmospheric probes into Venus, and fall slowly to the surface, making pressure and temperature measurements.[45]

- Vesper was a concept for a Venus orbiter focused on studying that planet's atmosphere.[75][76][77] It was one of three concepts to receive funds for further study in the 2006 Discovery selection.[76] Osiris and GRAIL were the other two, and eventually GRAIL was chosen and went on to be launched.[50]

- V-STAR (Venus Sample Targeting, Attainment and Return) is a Venus atmosphere sample return mission.[78][79] While returning samples from the surface of Venus has noted difficulties, a Discovery-class sample return from the upper atmosphere is being proposed.[78] Something along the lines of Stardust mission but using a free-return trajectory (it would not go into Venusian orbit).[78]

- VEVA (Venus Exploration of Volcanoes and Atmosphere) is an in atmosphere probe for Venus.[80] The centerpiece is a 7-day balloon flight through the atmosphere accompanied by various tiny probes dropped deeper into the planet's thick gases.[80]

- Venus Pathfinder, a long-duration Venus lander.[81]

- RAVEN, a Venus orbiter radar mapping mission.[82]

- VALOR, a Venus mission to study its atmosphere with a balloon.[83] Twin balloons would circumnavigate the planet over 8 Earth-days.[83]

- Venus Aircraft, a robotic atmospheric flight on Venus' atmosphere using a long-duration solar-powered aircraft system.[84] It would carry 1.5 kg of scientific payload and it must contend with violent wind, heat and a corrosive atmosphere.[84]

Selection process

Discovery 1 and 2

The first two Discovery missions were Near Earth Asteroid Rendezvous (NEAR) (later called Shoemaker NEAR) and Mars Pathfinder. These initial missions did not follow the same selection process that started once the program was under-way.[85] Mars Pathfinder was salvaged from the idea for a technology and EDL demonstrator from the Mars Environmental Survey program.[85] Also, one of the goals of Pathfinder was to support the Mars Surveyor program.[85] Later missions would be selected by a more sequential process involving Announcements of Opportunity.[85]

NEAR again has a slightly different background: when Discovery was established in 1990, soon after a working group for the program recommended that the first mission should be to a near-Earth asteroid.[86] A series of proposals limited to missions to a Near-Earth asteroid missions was reviewed in 1991.[86] What would be the NEAR spacecraft mission was formally selected in December 1993, after which a 2-year development period would follow prior to launch.[86] NEAR was launched on February 15, 1996, and arrived to orbit asteroid Eros on February 14, 2000.[86] Mars Pathfinder launched on December 4, 1996, and would land on the planet Mars on July 4, 1997, bringing along with it the first NASA Mars rover.[87]

Discovery 3 and 4

In August 1994, NASA made an announcement of opportunity for the next proposed Discovery missions.[88] There were 28 proposals submitted to NASA in October 1994:[88]

- ASTER- Asteroid Earth Return

- Comet Nucleus Penetrator

- Comet Nucleus Tour (CONTOUR)

- Cometary Coma Chemical Composition (C4)

- Diana (Lunar and Cometary Mission)

- FRESIP-A mission to Find the Frequency of Earth-sized Inner Planets

- Hermes Global Orbiter (Mercury Orbiter)

- Icy Moon Mission (Lunar Orbiter)

- Interlune-One (Lunar Rovers)[89]

- Jovian Integrated Synoptic Telescope (IO Torus investigation)

- Lunar Discovery Orbiter[90]

- Lunar Prospector (Lunar Orbiter) – chosen in February 1995 for Discovery 3.

- Mainbelt Asteroid Exploration/Rendezvous

- Mars Aerial Platform (Atmospheric)

- Mars Polar Pathfinder (Polar Lander)

- Mars Upper Atmosphere Dynamics, Energetics and Evolution

- Mercury Polar Flyby

- Near Earth Asteroid Returned Sample

- Origin of Asteroids, Comets and Life on Earth

- PELE: A Lunar Mission to Study Planetary Volcanism

- Planetary Research Telescope

- Rendezvous with a Comet Nucleus (RECON)

- Suess-Urey (Solar Wind Sample Return) – Discovery 4 finalist.

- Small Missions to Asteroids and Comets

- Stardust (Cometary/Interstellar Dust Return) – Discovery 4 finalist.

- Venus Composition Probe (Atmospheric)

- Venus Environmental Satellite (Atmospheric)

- Venus Multi-Probe Mission(Atmospheric)[91] – Discovery 4 finalist.

In February 1995, Lunar Prospector, a lunar orbiter mission, was selected for launch. Three other missions were left to undergo a further selection later in 1995 for the fourth Discovery mission, Stardust, Suess-Urey, and Venus Multiprobe.[88] Stardust, a comet sample return mission, was selected in November 1995 over the two other finalists.[92]

Discovery 5 and 6

In October 1997, NASA selected Genesis and CONTOUR as the next Discovery missions, out of 34 proposals that were submitted in December 1996.[93]

The five finalists were:[94]

- Aladdin (Mars' moon sample return)

- Comet Nucleus Tour (CONTOUR)

- Genesis (Solar wind sample return)

- Mercury Surface, Space Environment, Geochemistry and Ranging mission (MESSENGER)

- Venus Environmental Satellite (VESAT)

Discovery 7 and 8

In July 1999, NASA selected MESSENGER and Deep Impact as the next Discovery Program missions.[95] MESSENGER was the first Mercury orbiter and mission to that planet since Mariner 10, and the Deep Impact sent a projectile into the comet Tempel 1.[95] Both missions targeted a launch in late 2004 and the cost was constrained at about $300 million USD each.[95]

In 1998 five finalists had been selected to receive $375,000 USD to further mature their design concept.[96] The five proposals were selected out of perhaps 30 with the goal of achieving the best science.[96] Those missions were:[96]

- Aladdin

- Deep Impact

- MESSENGER

- Inside Jupiter

- Vesper

Aladdin and MESSENGER were also finalists in the 1997 selection.[96]

Discovery 9 and 10

26 proposals were submitted to the 2000 Discovery solicitation, with budget initially targeted at 300 million USD.[97] Three candidates were shortlisted in January 2001 for a phase-A design study: Dawn, Kepler, and INSIDE Jupiter.[98] INSIDE Jupiter was similar to a later New Frontiers mission called Juno; Dawn is a mission to asteroids Vesta and Ceres, and Kepler is a space telescope mission aimed to discover extrasolar planets. The three finalists received $450,000 USD to further mature the mission proposal.[99]

In December 2001, Kepler and Dawn were selected for flight by NASA.[100] At this time only 80 exoplanets had been detected, and that was part of the mission of Kepler, to look for more exoplanets, especially Earth-sized.[100][101] Both Kepler and Dawn were initially projected for launch in 2006.[97]

The Discovery Program fell on hard-times after this, with several mission experiencing cost overruns, and the CONTOUR mission experiencing an engine failure in orbit. Although both Dawn and Kepler would become widely praised success stories, they missed their somewhat ambitious 2006 launch target, launching in 2007 and 2009 respectively. Kepler would go on to receive a mission extensions, and Dawn likewise successfully orbited both Vesta and Ceres. Nevertheless, the next selection would take longer than previous as the program selection of new missions slowed down. As the successes of the new missions enhanced the image of the Discovery Program, the difficulties began to fade from the limelight. Also, the number of active missions in development or active began to increase as the program ramped up.

Discovery 11

The announcement of opportunity for this Discovery mission was released in April 2006.[102] There were three finalists for this Discovery selection including GRAIL (the eventual winner), OSIRIS, and VESPER.[103] OSIRIS was very similar to the later OSIRIS-REx mission, an asteroid sample return mission to 101955 Bennu, and Vesper, a Venus orbiter mission.[103] A previous proposal of Vesper had also been a finalist in the 1998 round of selection.[103] The three finalists were announced in October 2006 and awarded 1.2 million USD to further develop their propoals for the final round.[104]

In November 2007 NASA selected the GRAIL mission as the next Discovery mission, with a goal of mapping Lunar gravity and a 2011 launch.[105] There were 23 other proposals that were also under consideration.[105] The mission had budget of $375 million USD (then-year dollars) which included construction and also the launch.[105]

Discovery 12

This was an especially tough selection: coming on the heels of a successful Mars rover landing and the termination of the Mars Scout program (parent program of Phoenix and MAVEN), it meant that the proposals to the very popular red-planet competed with more obscure destinations. On the other hand, Titan had just been landed on by Huygens and Comets were getting the full-treatment by the flagship-class ESA Rosetta mission.

28 proposals were received in 2010; according to the BBC, 3 were for the Moon, 4 for Mars, 7 for Venus, 1 Jupiter, 1 to a Jupiter Trojan, 2 to Saturn, 7 to asteroids, and 3 to Comets.[106][107] Out of the 28, three finalists received US$3 million in May 2011 to develop a detailed concept study:[108]

- InSight, a Mars lander.

- Titan Mare Explorer (TiME) spacecraft for landing in, and floating on, a large methane-ethane sea on Saturn's moon Titan. A Titan moon "lake" lander was previously considered Titan Saturn System Mission and other concepts, but have lost out to other missions which have themselves been cancelled.

- Comet Hopper (CHopper) study cometary evolution by landing on a comet multiple times and observing its changes as it interacts with the Sun.

In August 2012, InSight was selected for development and launch.[109]. The mission launched successfully in May 2018 and is expected to reach Mars in November 2018.

Discovery 13 and 14

In February 2014, NASA released a Discovery Program 'Draft Announcement of Opportunity' for launch readiness date of December 31, 2021.[111] On 30 September 2015, NASA selected five mission concepts as finalists,[112][113] each received $3 million for one-year of further study and concept refinement.[114][115]

- Deep Atmosphere Venus Investigation of Noble gases, Chemistry, and Imaging (DAVINCI)

- Venus Emissivity, Radio Science, InSAR Topography and Spectroscopy (VERITAS)

- Near-Earth Object Camera (NEOCam)

- Lucy

- Psyche

On January 4, 2017, Lucy and Psyche were selected for the 13th and 14th Discovery missions, respectively.[2][116] Lucy will flyby five Jupiter trojans, asteroids which share Jupiter's orbit around the Sun, orbiting either ahead of or behind the planet.[117][116] Psyche will explore the origin of planetary cores by orbiting and studying the metallic asteroid 16 Psyche.[117]

Summary

Discovery has visited asteroids, comets, Mars, Mercury, and the Moon. There were two sample return missions, one for comet dust, another for solar wind, and that also detected interstellar dust, and one observatory focused on finding exoplanets.

Artists' impressions

| Discovery Program | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| NEAR Shoemaker 1996 |

Mars Pathfinder 1996 |

Lunar Prospector 1998 |

Stardust 1999 |

Genesis 2001 |

CONTOUR 2002 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| MESSENGER 2004 |

Deep Impact 2005 |

Dawn 2007 |

Kepler 2009 |

GRAIL 2011 |

InSight 2018 |

|

| ||||

| Lucy 2021 |

Psyche 2022 | ||||

Mission insignias

This section includes an image of the Discovery missions' patches or logos, as well as the launch year.

| Discovery Program | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| NEAR Shoemaker 1996 |

Mars Pathfinder 1996 |

Lunar Prospector 1998 |

Stardust 1999 |

Genesis 2001 |

CONTOUR 2002 |

|

|

|

|

| |

| MESSENGER 2004 |

Deep Impact 2005 |

Dawn 2007 |

Kepler 2009 |

GRAIL 2011 |

InSight 2018 |

|

| ||||

| Lucy 2021 |

Psyche 2022 | ||||

Launches

This section includes an image of the Discovery missions' rockets, as well as the launch year.

| Discovery Program | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|

|

| ||

| NEAR Shoemaker 1996 |

Mars Pathfinder 1996 |

Lunar Prospector 1998 |

Stardust 1999 |

Genesis 2001 |

CONTOUR 2002 | |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| MESSENGER 2004 |

Deep Impact 2005 |

Dawn 2007 |

Kepler 2009 |

GRAIL 2011 |

InSight 2018 | |

| Lucy 2021 |

Psyche 2022 | |||||

References

- ^ "Discovery Program Official Website (January 2016)". National Aeronautics and Space Administration (NASA). January 15, 2016. Archived from the original on January 15, 2016. Retrieved January 15, 2016.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ a b "Updated: NASA taps missions to tiny metal world and Jupiter Trojans". Science | AAAS. January 4, 2017. Retrieved January 4, 2017.

- ^ a b c d e "A Look Back at the Beginning: How the Discovery Program Came to Be" (PDF). NASA. 2010. Archived from the original (PDF) on March 1, 2011.

{{cite news}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ "NASA - NSSDCA - Spacecraft - Details". Nssdc.gsfc.nasa.gov. Retrieved May 2, 2018.

- ^ "Frequently Asked Questions". Near.jhuapl.edu. Retrieved May 2, 2018.

- ^ "NASA - NSSDCA - Spacecraft - Details". Nssdc.gsfc.nasa.gov. Retrieved May 2, 2018.

- ^ a b "NASA - NSSDCA - Spacecraft - Details". Nssdc.gsfc.nasa.gov. Retrieved May 2, 2018.

- ^ "U.S. space probe moving into lunar orbit - January 11, 1998". CNN. Retrieved April 28, 2018.

- ^ https://www.lpi.usra.edu/lunar/missions/prospector/overview/index.shtml

- ^ "Lunar Prospector Information". Nssdc.gsfc.nasa.gov. Retrieved April 28, 2018.

- ^ "NASA - NSSDCA - Spacecraft - Details". Nssdc.gsfc.nasa.gov. Retrieved May 2, 2018.

- ^ "NASA's Stardust: Good to the Last Drop". NASA.gov. NASA. Retrieved April 17, 2016.

- ^ a b "NASA - NSSDCA - Spacecraft - Details". Nssdc.gsfc.nasa.gov. Retrieved May 2, 2018.

- ^ "NASA - NSSDCA - Spacecraft - Details". Nssdc.gsfc.nasa.gov. Retrieved May 2, 2018.

- ^ https://nssdc.gsfc.nasa.gov/planetary/text/discovery_pr_971020.txt

- ^ "CONTOUR Mishap Investigation Board Report" (PDF). NASA. May 21, 2003. Archived from the original (PDF) on January 3, 2006.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ a b "NASA - NSSDCA - Spacecraft - Details". Nssdc.gsfc.nasa.gov. Retrieved May 2, 2018.

- ^ Mike Wall. "NASA's Long-lived MESSENGER Probe Slams into Mercury". Spacenews.com. Retrieved May 2, 2018.

- ^ Farewell, MESSENGER! NASA Probe Crashes Into Mercury. Mike Wall. Space News April 30, 2015.

- ^ a b "NASA - NSSDCA - Spacecraft - Details". Nssdc.gsfc.nasa.gov. Retrieved May 2, 2018.

- ^ "Deep Impact probe hits comet - Jul 4, 2005". CNN.com. July 4, 2005. Retrieved May 2, 2018.

- ^ "NASA - NSSDCA - Spacecraft - Details". Nssdc.gsfc.nasa.gov. Retrieved May 2, 2018.

- ^ https://www.wsj.com/articles/nasas-dawn-spacecraft-orbits-dwarf-planet-ceres-1425654292

- ^ Aron, Jacob (September 6, 2012). "Dawn departs Vesta to become first asteroid hopper". New Scientist. Archived from the original on September 7, 2012.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ "DAWN – A Journey to the Beginning of the Solar System". Dawn Mission Timeline. Jet Propulsion Laboratory. Archived from the original on October 19, 2013.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ "All About TESS, NASA's Next Planet Finder". Popularmechanics.com. October 30, 2013. Retrieved May 2, 2018.

- ^ Koch, David; Gould, Alan (March 2009). "Kepler Mission". NASA. Archived from the original on March 6, 2014.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ Clavin, Whitney; Chou, Felicia; Johnson, Michele (January 6, 2015). "NASA's Kepler Marks 1,000th Exoplanet Discovery, Uncovers More Small Worlds in Habitable Zones". NASA. Retrieved January 6, 2015.

- ^ "'Alien Earth' is among eight new far-off planets". BBC. January 7, 2015. Retrieved January 7, 2015.

- ^ Wall, Mike (September 5, 2013). "NASA Exoplanet archive". TechMediaNetwork. Retrieved June 15, 2013.

- ^ a b "NASA - Kepler". Archived from the original on November 5, 2013. Retrieved February 26, 2014.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ https://www.nasa.gov/pdf/582116main_GRAIL_launch_press_kit.pdf

- ^ Harwood, William (September 10, 2011). "NASA launches GRAIL lunar probes". CBS News. Archived from the original on September 11, 2011.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ "About GRAIL MoonKAM". Sally Ride Science. 2010. Archived from the original on April 27, 2010. Retrieved April 15, 2010.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ "NASA Approves 2018 Launch of Mars InSight Mission | NASA". Nasa.gov. Retrieved May 2, 2018.

- ^ "New NASA Mission to Take First Look Deep Inside Mars". NASA. August 20, 2012. Archived from the original on August 22, 2012.

{{cite news}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ "NASA Suspends 2016 Launch of InSight Mission to Mars". December 22, 2015.

- ^ a b Stephen Clark. "Earlier launch of NASA's Psyche mission touted as cost-saving measure – Spaceflight Now". Spaceflightnow.com. Retrieved May 2, 2018.

- ^ jobs (March 16, 2015). "Five Solar System sights NASA should visit: Nature News & Comment". Nature.com. Retrieved January 11, 2016.

- ^ Levison, Hal (January 2017). "Lucy: Surveying the Diversity of Trojan Asteroids" (PDF). Retrieved February 1, 2017.

- ^ Journey to a Metal World: Concept for a Discovery Mission to Psyche. (PDF) 45th Lunar and Planetary Science Conference (2014).

- ^ "NASA Moves Up Launch of Psyche Mission to a Metal Asteroid". NASA. May 24, 2017. Retrieved September 15, 2017.

- ^ "Deep Impact Heads to New Comet". Space.com. October 31, 2006. Archived from the original on November 2, 2006.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ "Discovery Program - Strofolio". NASA. Archived from the original on March 1, 2011.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ a b c d "3 Proposed Discovery Missions". National Space Science Data Center, NASA. Archived from the original on March 1, 2014.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ "1994LPI 25..985N Page 985". Astrophysics Data System. Harvard-Smithsonian Centre for Astrophysics. Retrieved February 28, 2014.

- ^ "NASA announces Discovery mission finalists". Space Today. January 4, 2001. Archived from the original on September 16, 2003.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ "Space Missions Roster". Lunar and Planetary Laboratory. The University of Arizona. Archived from the original on March 13, 2014.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ a b "Cosmic Dust - Messenger from Distant Worlds" (PDF). University Stuttgart. Archived from the original (PDF) on February 24, 2014.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ a b "NASA Announces Discovery Program Selections". News Release. NASA. October 30, 2006. Archived from the original on June 29, 2009.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ "OSIRIS-REx Factsheet" (PDF). University of Arizona. Archived from the original (PDF) on July 22, 2013.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ Bassett, S.; Sears, D. W. G. "The Hera Mission: Meeting Discovery Class Mission Precedents for Education and Public Outreach" (PDF). Arkansas Centre for Space and Planetary Sciences. Archived from the original (PDF) on December 28, 2005.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ a b Sears, Derek; Allen, Carl; Britt, Dan; Brownlee, Don; Franzen, Melissa; Gefert, Leon; Gorovan, Stephen; Pieters, Carle; Preble, Jeffrey; Scheeres, Dan; Scott, Ed (May 19, 2003). "The Hera Mission : Multiple Near-Earth Asteroid Sample Return" (PDF). Planetary Geosciences Group, Brown University. Archived from the original (PDF) on June 24, 2010.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ a b c Farquhar, Robert; Jen, Shao-Chiang; McAdams, Jim V. (September 12, 2000). "Extended-mission opportunities for a Discovery-class asteroid rendezvous mission". Astrophysics Data System. Harvard-Smithsonian Centre for Astrophysics. Bibcode:1993STIA...9581370F.

{{cite web}}: Missing or empty|url=(help) - ^ Sandford, Scott A.; A'Hearn, Michael; Allamandola, Louis J.; Britt, Daniel; Clark, Benton; Dworkin, Jason P.; Flynn, George; Glavin, Danny; Hanel, Robert; Hanner, Martha; Hörz, Fred; Keller, Lindsay; Messenger, Scott; Smith, Nicholas; Stadermann, Frank; Wade, Darren; Zinner, Ernst; Zolensky, Michael E. "The Comet Coma Rendezvous Sample Return" (PDF). Lunar and Planetary Institute. Archived from the original (PDF) on June 28, 2010.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ Riedel, Joseph E.; Marrese-Reading, Colleen; Lee, Young H. (June 19, 2013). "A Low-Cost NEO Micro Hunter-Seeker Mission Concept" (PDF). Low-Cost Planetary Missions Conference, LCPM-10. California Institute of Technology. Archived from the original (PDF) on March 1, 2014.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ Haberle, R. M.; Catling, D. C.; Chassefiere, E.; Forget, F.; Hourdin, F.; Leovy, C. B.; Magalhaes, J.; Mihalov, J.; Pommereau, J. P.; Murphy, J. R. "The Pascal Discovery Mission: A Mars Climate Network Mission". Astrophysics Data System. Harvard-Smithsonian Centre for Astrophysics. Bibcode:2000came.work..135H.

{{cite web}}:|access-date=requires|url=(help); Missing or empty|url=(help) - ^ "MUADEE: A Discovery-class mission for exploration of the upper atmosphere of Mars". Netherlands: Delft University of Technology. Archived from the original on February 4, 2015. Retrieved February 28, 2014.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ Colaprete, A.; Bellerose, J.; Andrews, D. "PCROSS - Phobos Close Rendezvous Observation Sensing Satellite". Astrophysics Data System. Harvard-Smithsonian Centre for Astrophysics. Bibcode:2012LPICo1679.4180C.

{{cite web}}:|access-date=requires|url=(help); Missing or empty|url=(help) - ^ Rivkin, A. S.; Chabot, N. L.; Murchie, S. L.; Eng, D.; Guo, Y.; Arvidson, R. E.; Trebi-Ollennu, A.; Seelos, F. P. "Merlin : Mars-Moon Exploration, Reconnaissance and Landed Investigation" (PDF). SETI. Archived from the original (PDF) on February 28, 2014.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ Lee, Pascal; Hoftun, Christopher; Lorbe, Kira. "Phobos and Deimos: Robotic Exploration in Advance of Humans to mars Orbit" (PDF). Concepts and Approaches for Mars Exploration (2012). Lunar and Planetary Institute. Archived from the original (PDF) on March 1, 2014.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ Lee, Pascal; Veverka, Joseph; Bellerose, Julie; Boucher, Marc; Boynton, John; Braham, Stephen; Gellert, Ralf; Hildebrand, Alan; Manzella, David; Mungas, Greg; Oleson, Steven; Richards, Robert; Thomas, Peter C.; West, Michael D. "HALL: A Phobos and Deimos Sample and Return Mission" (PDF). 41st Lunar and Planetary Science Conference (2010). Lunar and Planetary Institute. Archived from the original (PDF) on February 27, 2014.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ Pieters, C.; Murchie, S.; Cheng, A.; Zolensky, M.; Schultz, P.; Clark, B.; Thomas, P.; Calvin, W.; McSween, H.; Yeomans, D.; McKay, D.; Clemett, S.; Gold, R. "ALADDIN - Phobos-Deimos sample return". Astrophysics Data System. Harvard-Smithsonian Centre for Astrophysics. Bibcode:1997LPI....28.1111P.

{{cite web}}: Missing or empty|url=(help) - ^ a b Pieters, C.; Calvin, W.; Cheng, A.; Clark, B.; Clemett, S.; Gold, R.; McKay, D.; Murchie, S.; Mustard, J.; Papike, J.; Schultz, P.; Thomas, P.; Tuzzolino, A.; Yeomans, D.; Yoder, C.; Zolensky, M.; Barnouin-Jha, O.; Domingue, D. "ALADDIN: Exploration and Sample Return of Phobos and Deimos" (PDF). Lunar and Planetary Science. Lunar and Planetary Institute. Archived from the original (PDF) on September 5, 2004.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ Landis, Geoffrey A.; Oleson, Steven J.; McGuire, Melissa (January 9, 2012), "Design Study for a Mars Geyser Hopper" (PDF), 50th AIAA Aerospace Sciences Conference, Glenn Research Center, NASA, retrieved July 1, 2012

- ^ "Mars Geyser-Hopper (AIAA2012)" (PDF). NASA Technical Reports. NASA. Retrieved February 28, 2014.

- ^ Ravine, M. A.; Malin, M. C.; Caplinger, M. A. "Mars Geoscience Imaging at Centimetre-Scale (MAGIC) from Orbit" (PDF). Concepts and Approaches for Mars Exploration (2012). Lunar and Planetary Institute. Archived from the original (PDF) on October 29, 2013.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ "Red Dragon", Feasibility of a Dragon-derived Mars lander for scientific and human-precursor investigations (PDF), SpaceX, October 31, 2011, archived from the original (PDF) on June 16, 2012

{{citation}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ Duke, M. B.; Clark, B. C.; Gamber, T.; Lucey, P. G.; Ryder, G.; Taylor, G. J. "Sample Return Mission to the South Pole Aitken Basin" (PDF). Workshop on New Views of the Moon II. Lunar and Planetary Institute. Archived from the original (PDF) on November 9, 2004.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ "Robotics Institute: EXOMOON - A Discovery and Scout Mission Capabilities Expansion Concept". Robotics Institute, Carnegie Mellon University. June 15, 2011. Archived from the original on February 28, 2014.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ Clarke, T. L. "Planetary System Occultation from Lunar Halo Orbit (PSOLHO): A Discovery Mission". Astrophysics Data System. Harvard-Smithsonian Centre for Astrophysics. Bibcode:2003AAS...203.0305C.

{{cite web}}:|access-date=requires|url=(help); Missing or empty|url=(help) - ^ Klaus, K (October 24, 2012). "Concepts Leading to a Sustainable Architecture for Cislunar Development" (PDF). LEAG. Lunar and Planetary Institute. Archived from the original (PDF) on March 1, 2014.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ Neal, C. R.; Banerdt, W. B.; Alkalai, L. "Lunette: A Two-Lander Discovery-Class Geophysics Mission to the Moon" (PDF). 42nd Lunar and Planetary Science Conference (2011). Lunar and Planetary Institute. Archived from the original (PDF) on March 1, 2014.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ "Discovery Missions Under Consideration". Goddard Space Flight Centre, NASA. Archived from the original on March 1, 2014.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ "Deep Impact: Five Discovery Mission Proposals Selected for Feasibility Studies". Deep Impact. Press Releases. University of Maryland. November 12, 1998. Archived from the original on June 20, 2002.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ a b "NASA - Vesper Could Explore Earth's Fiery Twin". NASA. Archived from the original on August 23, 2007.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ "The VESPER Mission to Venus". Astrophysics Data System. Harvard-Smithsonian Centre for Astrophysics.

- ^ a b c "Venus Sample Targeting, Attainment, and Return (V-STAR)" (PDF). 2007 NASA Academy at the Goddard Space Flight Center. The Henry Foundation. Archived from the original (PDF) on March 15, 2012.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ Sweetser, Ted; Peterson, Craig; Nilsen, Erik; Gershman, Bob. "Venus Sample Return Missions - A Range of Science, A Range of Costs" (PDF). California Institute of Technology. Archived from the original (PDF) on May 26, 2010.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ a b Klaasen, Kenneth; Greeley, Ronald (March 31, 2003). "VEVA Discovery mission to Venus: exploration of volcanoes and atmosphere". Acta Astronautica. 52. Science Direct: 151–158. Bibcode:2003AcAau..52..151K. doi:10.1016/s0094-5765(02)00151-0.

- ^ Lorenz, Ralph D.; Mehoke, Doug; Hill, Stuart. "Venus Pathfinder: A Stand-Alone Long-Lived Venus Lander Mission Concept" (PDF). 8th International Planetary Probe Workshop (IPPW-8). National Institute of Aerospace. Archived from the original (PDF) on February 27, 2014.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ Sharpton, V. L.; Herrick, R. R.; Rogers, F.; Waterman, S. "RAVEN - High-resolution Mapping of Venus within a Discovery Mission Budget". Astrophysics Data System. Harvard-Smithsonian Centre for Astrophysics. Bibcode:2009AGUFM.P31D..04S.

{{cite web}}:|access-date=requires|url=(help); Missing or empty|url=(help) - ^ a b Baines, Kevin H.; Hall, Jeffery L.; Balint, Tibor; Kerzhanovich, Viktor; Hunter, Gary; Atreya, Sushil K.; Limaye, Sanjay S.; Zahnle, Kevin. "Exploring Venus with Balloons: Science Objectives and Mission Architectures for small and Medium-Class Missions" (PDF). Georgia Tech Library. Archived from the original (PDF) on February 27, 2014.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ a b Landis, Geoffrey A.; LaMarre, Christopher; Colozza, Anthony (January 14, 2002). "NASA TM-2002-0819 : Atmospheric Flight on Venus". American Institute of Aeronautics and Astronautics, The Pennsylvania State University. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.195.172.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - ^ a b c d [1]

- ^ a b c d "02-0483D Farquhar.Indd" (PDF). Retrieved April 28, 2018.

- ^ "NASA Glenn Participation in Mars Pathfinder Mission | NASA". Nasa.gov. December 4, 1996. Retrieved April 28, 2018.

- ^ a b c "Discover 95 : Mission to the Moon, Sun, Venus and a Comet Picked for Discovery - NASA". Retrieved April 28, 2018.

- ^ "Interlune-One: A Scientific Mission Across the Surface of the Moon (PDF Download Available)". Researchgate.net. Retrieved January 11, 2016.

- ^ "UA scientist seeking big bucks from NASA - Tucson Citizen Morgue, Part 2 (1993-2009)". Tucsoncitizen.com. January 27, 1995. Retrieved January 11, 2016.

- ^ "NASA Technical Reports Server (NTRS) - Venus Multiprobe Mission". Ntrs.nasa.gov. Retrieved January 11, 2016.

- ^ "STARDUST Selected as Discovery Flight". Stardust.jpl.nasa.gov. Retrieved January 11, 2016.

- ^ "Missions to Gather Solar Wind Samples and Tour Three Comets Selected as Next Discovery Program Flights" (TXT). Nssdc.gsfc.nasa.gov. Retrieved January 11, 2016.

- ^ "News from Space - LPIB 82". Lpi.usra.edu. September 30, 2002. Retrieved January 11, 2016.

- ^ a b c "NASA Selects Missions to Mercury and a Comet's Interior as Next Discovery Flights". Nssdc.gsfc.nasa.gov. Retrieved January 11, 2016.

- ^ a b c d "Five Discovery Mission Proposals Selected For Feasibility Studies" (TXT). Nasa.gov. Retrieved January 11, 2016.

- ^ a b Susan Reichley (December 21, 2001). "2001 News Releases - JPL Asteroid Mission Gets Thumbs Up from NASA". Jpl.nasa.gov. Retrieved January 11, 2016.

- ^ "NASA announces Discovery mission finalists". Spacetoday.net. January 4, 2001. Retrieved January 11, 2016.

- ^ Richard StengerCNN.com Writer. "Space - NASA selects finalists for next Discovery mission - January 5, 2001". CNN.com. Retrieved January 11, 2016.

{{cite news}}:|author=has generic name (help) - ^ a b "NASA". Nasa.gov. Retrieved January 11, 2016.

- ^ "Science Analysis Support for NASA Discovery Program's Kepler Extended Mission | SETI Institute". Seti.org. Retrieved January 11, 2016.

- ^ Cain, Fraser. "Back to Venus with Vesper". Universe Today. Retrieved January 11, 2016.

- ^ a b c Paolo Ulivi; David M. Harland (September 16, 2014). "Robotic Exploration of the Solar System: Part 4: The Modern Era 2004 –2013". Books.google.com. p. 349. Retrieved January 11, 2016.

- ^ "NASA - NASA Announces Discovery Program Selections". Nasa.gov. November 2, 2008. Retrieved January 11, 2016.

- ^ a b c "NASA aiming to look inside the moon - Technology & science - Space - Space.com". NBC News. September 6, 2011. Retrieved January 11, 2016.

- ^ Hand, Eric (September 2, 2011). "Venus scientists fear neglect". Nature. Archived from the original on May 26, 2012.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ Jpl, Nasa (August 20, 2012). "Mars Mobile". Marsmobile.jpl.nasa.gov. Retrieved January 11, 2016.

- ^ "NASA Selects Investigations For Future Key Planetary Mission". NASA. Retrieved May 6, 2011.

- ^ Vastag, Brian (August 20, 2012). "NASA will send robot drill to Mars in 2016". The Washington Post.

- ^ Kane, Van (February 20, 2014). "Boundaries for the Next Discovery Mission Selection". Future Planets. Archived from the original on March 7, 2014.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ "NASA Discovery Program Draft Announcement of Opportunity". NASA Science Mission Directorate. SpaceRef. February 19, 2014.

- ^ Stephen Clark. "NASA might pick two Discovery missions, but at a price". Spaceflight Now. Retrieved January 11, 2016.

- ^ Brown, Dwayne C.; Cantillo, Laurie (September 30, 2015). "NASA Selects Investigations for Future Key Planetary Mission". NASA News. Washington, D.C. Retrieved October 1, 2015.

- ^ Clark, Stephen (February 24, 2014). "NASA receives proposals for new planetary science mission". Space Flight Now. Retrieved February 25, 2015.

- ^ Kane, Van (December 2, 2014). "Selecting the Next Creative Idea for Exploring the Solar System". Planetary Society. Retrieved February 10, 2015.

- ^ a b "NASA Selects Two Missions to Explore the Early Solar System". January 4, 2017. Retrieved January 4, 2017.

- ^ a b Chang, Kenneth (January 6, 2017). "A Metal Ball the Size of Massachusetts That NASA Wants to Explore". The New York Times. Retrieved January 7, 2017.

External links

- Official NASA website for Discovery Program

- Official NASA website for Discovery and New Frontiers Programs Office