Dubstep

| Dubstep | |

|---|---|

| Stylistic origins | Dub, grime, 2-step, drum and bass |

| Cultural origins | Early 2000s, Croydon, United Kingdom |

| Typical instruments | Sequencer, turntables, sampler, drum machine, synthesizer, keyboard, personal computer |

| Subgenres | |

| Post-dubstep | |

| Fusion genres | |

| Dubstyle, drumstep | |

| Other topics | |

| List of musicians | |

Dubstep is a genre of electronic dance music that originated in south London, England. Its overall sound has been described as "tightly coiled productions with overwhelming bass lines and reverberant drum patterns, clipped samples, and occasional vocals".[1]

The earliest dubstep releases date back to 1998 and were darker, more experimental, instrumental dub remixes of 2-step garage tracks attempting to incorporate the funky elements of breakbeat, or the dark elements of drum and bass into 2-step, which featured B-sides of single releases. In 2001, this and other strains of dark garage music began to be showcased and promoted at London's night club Forward (sometimes also referred to as FWD>>), which went on to be considerably influential to the development of dubstep. The term "dubstep" in reference to a genre of music began to be used by around 2002, by which time stylistic trends used in creating these remixes started to become more noticeable and distinct from 2-step and grime.

A very early supporter of the sound was BBC Radio 1 DJ John Peel, who started playing it from 2003 onwards. In 2004, the last year of his show, his listeners voted Distance, Digital Mystikz and Plastician (formerly Plasticman) in their top 50 for the year.[2] Dubstep started to spread beyond small local scenes in late 2005 and early 2006; many websites devoted to the genre appeared on the internet and thus aided the growth of the scene, such as dubstepforum, the download site Barefiles and blogs such as gutterbreakz.[3] Simultaneously, the genre was receiving extensive coverage in music magazines such as The Wire and online publications such as Pitchfork Media, with a regular feature entitled The Month In: Grime/Dubstep. Interest in dubstep grew significantly after BBC Radio 1 DJ Mary Anne Hobbs started championing the genre, beginning with a show devoted to it (entitled "Dubstep Warz") in January 2006.[4][5][6]

Characteristics

Dubstep's early roots are in the more experimental releases of UK garage producers, seeking to incorporate elements of drum and bass into the South London-based 2-step garage sound. These experiments often ended up on the B-side of a white label or commercial garage release.[4][7][8] Dubstep is generally instrumental. Similar to a vocal garage hybrid - grime - the genre's feel is commonly dark; tracks frequently use a minor key and can feature dissonant harmonies such as the tritone interval within a riff. Other distinguishing features often found are the use of samples, a propulsive, sparse rhythm,[9] and an almost omnipresent sub-bass. Some dubstep artists have also incorporated a variety of outside influences, from dub-influenced techno such as Basic Channel to classical music or heavy metal.[9][10][11]

Rhythm

Dubstep rhythms are usually syncopated, and often shuffled or incorporating tuplets. The tempo is nearly always in the range of 138-142bpm.[9] In its early stages, dubstep was often more percussive, with more influences from 2-step and grime drum patterns. A lot of producers were also experimenting with tribal drum samples, a notable example being Loefah's early release "Truly Dread". Over time, key producers at the time started to experiment with the half-step rhythm which created more of a spacious vibe, and head-nodding rhythm, a feature which started to be used more and more and has become a signature of the genre. Similarly, the half-step rhythm also started to dominate grime, and producers started to lose the more complex and jerky rhythms influenced from 2-step, and started to work with more hip-hop influenced beats.

Dubstep rhythms typically do not follow the four-to-the-floor patterns common in many other styles of electronic dance music such as techno and house but tend to rely on longer percussion loops than the four-bar phrases present in much techno or house. Often, a track's percussion will follow a pattern which when heard alone will appear to be playing at half the tempo of the track; the double-time feel is instead achieved by other elements, usually the bassline. An example of this tension generated by the conflicting tempo can be listened on the right. The song features a very sparse rhythm almost entirely composed of kick drum, snare drum, and a sparse hi-hat, with a distinctly half time implied 71bpm tempo. The track is instead propelled by a sub-bass following a four-to-the-floor 142bpm pattern.

In an Invisible Jukebox interview with The Wire, Kode9 commented on a DJ MRK1 (formerly Mark One) track, observing that listeners "have internalized the double-time rhythm" and the "track is so empty it makes [the listener] nervous, and you almost fill in the double time yourself, physically, to compensate".[12]

Wobble bass

One characteristic of certain strands of dubstep is the wobble bass, where an extended bass note is manipulated rhythmically. This style of bass is typically produced by using a low frequency oscillator to manipulate certain parameters of a synthesizer such as volume, distortion or filter cutoff. The resulting sound is a timbre that is punctuated by rhythmic variations in volume, filter cut-off, or distortion. This style of bass is a driving factor in some variations of dubstep, particularly at the more club-friendly end of the spectrum - a subgenre which has been termed 'brostep' by some.[13]

Structure, bass drops, rewinds and MCs

Originally, dubstep releases had some structural similarities to other genres like drum and bass and UK garage. Typically this would comprise an intro, a main section (often incorporating a bass drop), a midsection, a second main section similar to the first (often with another drop), and an outro.

Many dubstep tracks incorporate one or more "bass drops", a characteristic inherited from drum and bass. Typically, the percussion will pause, often reducing the track to silence, and then resume with more intensity, accompanied by a dominant subbass (often passing portamento through an entire octave or more, as in the audio example). However, this is by no means a completely rigid characteristic, rather a trope; a large portion of seminal tunes from producers like Kode9 and Horsepower Productions have more experimental song structures which don't rely on a drop for a dynamic peak - and in some instances don't feature a bass drop at all.

Rewinds (or reloads)[14] are another technique used by dubstep DJs. If a song seems to be especially popular, the DJ will 'spin back' the record by hand without lifting the stylus, and play the track in question again. Rewinds are also an important live element in many of dubstep's precursors; the technique originates in dub reggae soundsystems, is a standard of most pirate radio stations and is also used at UK garage and jungle nights.[15]

Taking direct cues from Jamaica's lyrically sparse deejay and toasting mic styles in the vein of reggae pioneers like U-Roy, the MC's role in dubstep's live experience is critically important to its impact.[16] As the music is largely instrumental, the MC operates in a similar context to drum and bass and is generally more of a complement to the music rather than the deliverer of lyrical content.[citation needed]

Notable mainstays in the live experience of the sound are MC Sgt Pokes and MC Crazy D from London, and Juakali from Trinidad.[17][18][19][20] Production in a studio environment seems to lend itself to more experimentation. Kode9 has collaborated extensively with the Spaceape, who MCs in a dread poet style. Kevin Martin's experiments with the genre are almost exclusively collaborations with MCs such as Warrior Queen, Flowdan, and Tippa Irie. Skream has also featured Warrior Queen and grime artist JME on his debut album, Skream!. Plastician, who was one of the first DJ's to mix the sound of grime and dubstep together,[10] has worked with notable grime setup Boy Better Know as well as renowned Grime MC's such as Wiley, Dizzee Rascal and Lethal Bizzle. He has also released tracks with a dubstep foundation and grime verses over the beats.[21] Coki and Mala of Digital Mystikz have experimented with abrupt, 16-bar intros and have produced tracks with dub vocalists,[citation needed] and dubstep artist and label co-owner Sam Shackleton has moved toward productions which fall outside the usual dubstep tempo, and sometimes entirely lack most of the common tropes of the genre.[22]

History

Early foundations

While dubstep is its own distinct form of electronic music, its roots are surely located within Jamaican dub music and sound system cultures. Jamaican sound systems were "large mobile hi-fi or disco...[with] an emphasis on the reproduction of bass frequencies, its own aesthetics and a unique mode of consumption".[23] These soundsystems represented the appearance of records (dub plates) as modes of legitimate artistic creation. This was an integral moment in the evolution of electronic musics, both in Britain and worldwide.

Jamaican sound system culture gave birth to the dub variety of reggae music, which itself originated many of dubstep's characteristic sounds and sonic techniques. Features like sub-bass (bass below 90 Hz), skittering and jittery drums (which would later be termed '2-step'), distortive echo and reverberation effects were all used prominently.[24] These features, along with held over soundsystem techniques, went on to form the crux of numerous electronic musics which emerged from Britain, including jungle, garage, and eventually dubstep.

Sub-bass, however, has also been present in British dance music since the early 1990s - LFO by LFO on the Warp Records label, released in 1990 features sub-bass throughout, as does the B-side mix of "Charly" by The Prodigy (1991). Altern 8's early breakbeat house/techno release Infiltrate 202 - also from 1991 - begins with the phrase, "watch yer bassbins" referring to the heavy sub-bass running throughout the track.[citation needed] Another early sub-bass tune is Some Justice by Urban Shakedown, made in 1992 entirely on two Commodore Amiga 500 computers, achieved some chart success upon its release. The sub-bass in this track also rises and falls initially in a rather slow, then later speeding-up, oscillation pattern similar to a dubstep bassline.

1999–2002: origins

The sound of dubstep originally came out of productions by El-B,[7] Steve Gurley,[7] Oris Jay,[11] and Zed Bias[25][26] in 1999-2000. Ammunition Promotions, who run the influential club Forward>> and have managed many proto dubstep record labels (including Tempa, Soulja, Road, Vehicle, Shelflife, Texture, Lifestyle and Bingo),[5][11] began to use the term "dubstep" to describe this style of music in around 2002. The term's use in a 2002 XLR8R cover story (featuring Horsepower Productions on the cover) contributed to it becoming established as the name of the genre.[25][27] It gained full acceptance with the Dubstep Allstars Vol 1 CD (Tempa) mixed by DJ Hatcha.[citation needed]

The club Forward>> was originally held at the Velvet Rooms in London's Soho and is now running every Thursday at Plastic People in Shoreditch, east London.[9] Founded in 2001, Forward>> was critical to the development of dubstep, providing the first venue devoted to the sound and an environment in which dubstep producers could premier new music.[28] Around this time, Forward>> was also incubating several other strains of dark garage hybrids, so much so that in the early days of the club the coming together of these strains was referred to as the "Forward>> sound".[29] An online flyer from around this time encapsulated the Forward>> sound as "b-lines to make your chest cavity shudder."[30]

Forward>> also ran a radio show on east London pirate station Rinse FM, hosted by Kode9.[31] The original Forward>> line ups included Hatcha, Youngsta, Kode9, Zed Bias, Oris Jay,[11] Slaughter Mob, Jay Da Flex, Slimzee and others, plus regular guests. The line up of residents has changed over the years to include Youngsta, Hatcha, Geeneus and Plastician, with Crazy D as MC/host. Producers including D1, Skream and Benga make regular appearances.[28]

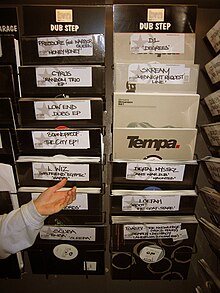

Another crucial element in the early development of dubstep was the Big Apple Records record shop in Croydon.[5] Key artists such as Hatcha and later Skream worked in the shop (which initially sold early UK Hardcore / Rave, Techno and House and later, garage and drum and bass, but evolved with the emerging dubstep scene in the area),[7] while Digital Mystikz were frequent visitors. El-B, Zed Bias, Horsepower Productions, Plastician, N Type, Walsh and a young Loefah regularly visited the shop as well.[5] The shop and its record label have since closed down[25] and reopened under the name Mixing Records under new management before closing down again in 2010. The shop's site is currently unused and still stands in the north end of Surrey Street, Croydon.

In an article in The Guardian, Simon Reynolds examined the idea of any links between the recreational use of ketamine, a dissociative drug, and the origins of dubstep, writing that a connection "would certainly explain a lot", though also conceding "it could all be just rumour".[32]

2002–2005: evolution

Throughout 2003, DJ Hatcha pioneered a new direction for dubstep on Rinse FM and through his sets at Forward>>.[5][26] Playing sets cut to 10" one-off reggae-style dubplates, he drew exclusively from a pool of new South London producers—first Benga and Skream,[26] then also Digital Mystikz and Loefah—to begin a dark, clipped and minimal new direction in dubstep.[33]

At the end of 2003, running independently from the pioneering FWD night, an event called Filthy Dub, co promoted by Plastician, and partner David Carlisle started happening regularly. It was there that Skream, Benga, N Type, Walsh, Chef, Loefah and Cyrus made their debuts as DJ's. South London collective Digital Mystikz (Mala and Coki), along with labelmates and collaborators Loefah and MC Sgt Pokes soon came into their own, bringing sound system thinking, dub values, and appreciation of jungle bass weight to the dubstep scene.[25] Digital Mystikz brought an expanded palette of sounds and influences to the genre, most prominently reggae and dub, as well as orchestral melodies.[34]

After releasing 12"s on Big Apple, they founded DMZ Records, which has released fourteen 12"s to date. They also began their night DMZ, held every two months in Brixton,[35] a part of London already strongly associated with reggae.[36] DMZ has showcased new dubstep artists such as Skream, Kode 9, Benga, Pinch, DJ Youngsta, Hijak, Joe Nice and Vex'd. DMZ's first anniversary event (at the Mass venue, a converted church) saw fans attending from places as far away as Sweden, the U.S., and Australia, leading to a queue of 600 people[37] at the event. This forced the club to move from its regular 400-capacity space[6] to Mass' main room, an event cited as a pivotal moment in dubstep's history.[11][38]

In 2004, Richard James' label, Rephlex, released two compilations that included dubstep tracks - the (perhaps misnamed) Grime and Grime 2. The first featured Plasticman, Mark One and Slaughter Mob,[39] with Kode 9, Loefah and Digital Mystikz appearing on the second.[40] These compilations helped to raise awareness of dubstep at a time when the grime sound was drawing more attention,[25] and Digital Mystikz and Loefah's presence on the second release contributed to the success of their DMZ club night.[41] Soon afterwards, the Independent on Sunday commented on "a whole new sound", at a time when both genres were becoming popular, stating that "grime" and "dubstep" were two names for the same style, which was also known as "sublow", "8-bar" and "eskibeat".[42]

2005–2008: growth

In the summer of 2005, Forward>> brought grime DJs to the fore of the line up.[43] Building on the success of Skream's grimey anthem "Midnight Request Line," the hype around the DMZ night and support from online forums (notably dubstepforum.com)[9] and media,[6] the scene gained prominence after former Radio 1 DJ Mary Anne Hobbs gathered top figures from the scene for one show, entitled "Dubstep Warz", (later releasing the compilation album Warrior Dubz).[37] The show created a new global audience for the scene, after years of exclusively UK underground buzz.[9] Burial's self-titled album appearing in many critics' "Best of..." lists for the year, notably The Wire's Best Album of 2006.[44] The sound was also featured prominently in the soundtrack for the 2006 sci-fi film Children of Men,[45] which included Digital Mystikz, Random Trio, Kode 9, Pressure and DJ Pinch.[46] Ammunition also released the first retrospective compilation of the 2000-2004 era of dubstep called The Roots of Dubstep, co-compiled by Ammunition and Blackdown on the Tempa Label.[47]

The sound's first North American ambassador, Baltimore DJ Joe Nice helped kickstart its spread into the continent.[9] Regular Dubstep club nights started appearing in cities like New York,[48] San Francisco,[27] Seattle, Montreal, Houston, and Denver,[49] while Mary Anne Hobbs curated a Dubstep showcase at 2007's Sónar festival in Barcelona.[11] Non-British artists have also won praise within the larger Dubstep community.[11] The dynamic dubstep scene in Japan is growing quickly despite its cultural and geographical distance from the West. Such DJ/producers as Goth-trad, Hyaku-mado, Ena and Doppelganger are major figures in the Tokyo scene.[50] Joe Nice has played at DMZ,[51] while the fifth installment of Tempa's "Dubstep Allstars" mix series (released in 2007) included tracks by Finnish producer Tes La Rok and Americans JuJu and Matty G.[52] Following on from Rinse FM's pioneering start; three internet based radio station's called SubFM, DubstepFM and DubTerrain started to play the sound exclusively with 24 hour broadcasting featuring show archives and live DJ shows.

Techno artists and DJs began assimilating dubstep into their sets and productions.[11] Shackleton's "Blood On My Hands" was remixed by minimal techno producer Ricardo Villalobos (an act reciprocated when Villalobos included a Shackleton mix on his "Vasco" EP)[53] and included on a mix CD by Panoramabar resident Cassy.[11] Ellen Allien and Apparat's 2006 song "Metric" (from the Orchestra of Bubbles album),[54][55] Modeselektor's "Godspeed" (from the 2007's Happy Birthday! album, among other tracks on that same album) and Roman Flugel's remix of Riton's "Hammer of Thor" are other examples of dubstep-influenced techno.[11] Berlin's Hard Wax record store (operated by influential[56] dub techno artists Basic Channel)[57][58] has also championed Shackleton's Skull Disco label, later broadening its focus to include other dubstep releases.[10]

The summer of 2007 saw dubstep's musical palette expand further, with Benga and Coki scoring a crossover hit (in a similar manner to Skream's "Midnight Request Line") with the track "Night", which gained widespread play from DJs in a diverse range of genres. BBC Radio 1 DJ Gilles Peterson named it his record of 2007, and it was also a massive hit in the equally bassline-orientated, but decidedly more four-to-the-floor genre of bassline house,[59] whilst Burial's late 2007 release Untrue (which was nominated for the 2008 Nationwide Mercury Music Prize in the UK) incorporated extensive use of heavily manipulated, mostly female, 'girl next door' vocal samples.[60] Burial has spoken at length regarding his intent to reincorporate elements of musical precursors such as 2-step garage and house into his sound.[61]

Much like drum and bass before it, dubstep has started to become incorporated into other media, particularly in the United Kingdom. In 2007, Benga, Skream, and other dubstep producers provided the soundtrack to much of the second series of Dubplate Drama, which aired on Channel 4 with a soundtrack CD later released on Rinse Recordings. The sound also featured prominently in the second series of the teen drama Skins, which also aired on Channel 4 in early 2008.

In the summer of 2008, Mary Anne Hobbs invited Cyrus, Starkey, Oneman, DJ Chef, Silkie, Quest, Joker, Nomad, Kulture and MC Sgt Pokes to the BBC's Maida Vale studios for a show called Generation Bass.[62][63][64][65] The show was the evolution from her seminal BBC Radio 1 Dubstepwarz Show in 2006, and further documented another set of dubstep's producers.

In the autumn of 2008, a limited pressing 12" called "Iron Devil"[66] was released featuring Lee Scratch Perry and Prince Far-I in a dubstep style, including a tune based on the Perry riddim used on reggae hits like "Disco Devil", "Chase The Devil", and "Croaking Lizard". This was the first recorded example of a founder of Jamaican dub style acknowledging dubstep and creating new music in the genre, reinforcing the connection of dubstep to its roots in Jamaican dub reggae at a time when it seemed dubstep was moving away from its reggae underpinnings.

As the genre has spread to become an international rather than UK-centric scene, it has also seen a number of women making headway into the scene in a variety of ways. Alongside Soulja of Ammunition Promotions and Mary Anne Hobbs, an influx of female producers, writers, photographers and DJs all have broken through in the up-til-then male orientated scene. With key 12" releases on Hyperdub, Immigrant and Hotflush Recordings, producers Vaccine, Subeena and Ikonika have introduced a palette of new sounds and influences to the genre, such as double-time bass drums, 8-bit video game samples, hand percussion and lushly arranged strings.[67] Mary Anne Hobbs commented that the mood at dubstep nights is less aggressive, or more meditative, leading to a larger female attendance at events than with the genre's precursors, noting "Grime and drum 'n' bass raves tend to be quite aggy. People in dubstep clubs tend to have a more meditative approach, which is inviting to females. You see the female-to-male ratio constantly going up – it’s got the potential to be 40:60".[67]

Journalists Melissa Bradshaw,[68][69] Emma Warren,[70][71] and dubstep documentarian and photographer Georgina Cook have all had an impact on the cultural importance of the music. Cook's Drumz of the South flickr page documents the evolution of the scene in a photographic timeline of sorts, and was for a time the only photographic archive of the key events such as the early FWD and DMZ nights in London.[67][72][73][74]

2009 to present: mainstream influence

This section may need to be rewritten to comply with Wikipedia's quality standards. (March 2011) |

The influence of dubstep on more commercial or popular genres can be identified as far back as 2007, with artists such as Britney Spears using dubstep sounds; critics observed a dubstep influence in the song "Freakshow", from the 2007 album Blackout, which Tom Ewing described as "built around the 'wobbler' effect that's a genre standby."[75][76] Benga and Coki's single "Night" still continued to be a popular track on the UK dance chart more than a year after its release in late 2007, still ranking in the top five at the start of April 2008 on Pete Tong's BBC Radio 1 dance chart list.[77]

However the year 2009 saw the dubstep sound gaining further worldwide recognition, often through the assimilation of elements of the sound into other genres, in a manner similar to drum and bass before it. At the start of the year, UK electronic duo La Roux put their single "In for the Kill" in the remix hands of Skream.[78][79] They then gave remix duties of "I'm Not Your Toy" to Nero and then again with their single "Bulletproof" being remixed by Zinc. The same year, London producer Silkie released an influential album City Limits Vol. 1 on the Deep Medi label, using 70s funk and soul reference points, a departure from the familiar strains of dub and UK garage.[80] The sound also continued to interest the mainstream press with key articles in magazines like Interview, New York, and The Wire, which featured producer Kode9 on its May 2009 cover. XLR8R put Joker on the cover of its December 2009 issue.[17][81][82][83] By the end of 2009, The New York Times, XLR8R, NME and The Sunday Times all reviewed the genre.[84][85][86][87]

Throughout 2010 and 2011, dubstep was beginning to hit the pop charts, with "I Need Air" by Magnetic Man reaching number 10 in the UK singles chart. This presented a turning point in the popularity of mainstream dubstep amongst UK listeners as it was placed on rotation on BBC Radio 1.[88] "Katy On a Mission" by Katy B (produced by Benga) followed, debuting at number 5 in the UK singles chart, and stayed in the top 10 for five more weeks.[89] In February 2011, Chase & Status's second album No More Idols reached No.2 in the UK album chart.[90] On May 01, 2011, Nero's third single "Guilt" from their album reached number 8 in the Official UK Singles Chart, their highest placing single to date. [91] In April of 2011, "dubbox", the industry's first application designed for the mobile creation of dubstep music, was released for the iPhone and reached the Top 25 Best Selling Music Apps in the UK its first week.

In a move foreshadowed by endorsements of the sound from R&B, hip-hop and recently, mainstream figures such as Rihanna, or Public Enemy's Hank Shocklee,[92] Snoop Dogg collaborated with dubstep producers Chase & Status, providing a vocal for their 'underground anthem' "Eastern Jam".[93] The 2011 Britney Spears track "Hold It Against Me" was also responsible for promoting dubstep tropes within a mainstream pop audience,[94]. Rihanna's Rated R album released such content the very year dubstep saw a spike, containing 3 dubstep tracks.[95] Such events propelled the genre into the biggest radio markets overnight, with considerable airplay.[96] Other hip-hop artists like Xzibit added their vocals to dubstep instrumental tracks for the mixtape project Mr Grustle & Tha Russian Dubstep LA Embrace The Renaissance Vol. 1 Mixed by Plastician.[96][97] In summer 2009, female rapper and actress Eve used Benga's "E Trips"; adding her own verses over the beat to create a new tune called "Me N My"; the first single on her album Flirt. The track was co-produced by Benga and hip hop producer Salaam Remi.[98][99]

See also

References

- ^ "Explore Music: Dubstep". Allmusic. Rovi Corporation. Retrieved 31 March 2011.

- ^ "Keeping It Peel: Festive 50s - 2004". BBC Radio One. BBC. Retrieved 31 March 2011.

- ^ Wilson, Michael (1 November 2006). "Bubble and Squeak: Michael Wilson on Dubstep". Artforum International. Retrieved 31 March 2011.

- ^ a b de Wilde, Gervase (14 October 2006). "Put a Bit of Dub in Your Step". The Daily Telegraph. London: Telegraph Media Group. Retrieved 31 March 2011.

- ^ a b c d e O'Connell, Sharon (4 October 2006). "Dubstep". Time Out London. Time Out Group. Retrieved 21 June 2007.

- ^ a b c Clark, Martin (16 November 2006). "The Year in Grime and Dubstep". Pitchfork Media. Retrieved 21 June 2007.

- ^ a b c d "The Primer: Dubstep". The Wire (279). April 2011. ISSN 0952-0686.

- ^ Pearsall (18 June 2005). "Interview: Plasticman". Riddim.ca. Retrieved 31 March 2011.

- ^ a b c d e f g McKinnon, Matthew (30 January 2007). "South London Calling". CBC.ca. Retrieved 31 March 2011.

- ^ a b c Clark, Martin (23 May 2007). "Grime / Dubstep". Pitchfork Media. Retrieved 14 July 2007.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j Sande, Kiran (7 June 2007). "Dubstep 101". Resident Advisor. Retrieved 31 March 2011.

- ^ "Invisible Jukebox". The Wire (269). July 2006. ISSN 0952-0686.

- ^ Clark, Martin (6 November 2009). "The Year in Grime / Dubstep: The Year in Dubstep, Grime, and Funky 2009". Pitchfork Media. Retrieved 1 April 2011.

No summary of the year in dubstep would be complete without the ever-expanding wobble side of the scene, recently hilariously and accurately renamed "brostep." In the UK, the wobble sound is now the default dubstep position for many fans, as the scene commands a increasing share of the Friday night/student/super club market.

- ^ "Interview: Joe Nice". GetDarker. 15 August 2006. Archived from the original on 28 September 2007. Retrieved 31 March 2011.

- ^ Clark, Martin (14 July 2006). "The Month In: Grime/Dubstep". Pitchfork Media. Retrieved 31 March 2011.

- ^ Earp, Matt (30 August 2006). "Low End Theory: Dubstep Merchants". XLR8R. Amalgam Media. Retrieved 31 March 2011.

- ^ a b Hammond, Bob (20 July 2008). "How Low Can it Go: The Evolution of Dubstep". New York. New York Media Holdings. Retrieved 31 March 2011.

- ^ Warren, Emma (4 March 2007). "Rising Star: DMZ, Music Collective". The Observer. London: Guardian Media Group. Retrieved 31 March 2011.

- ^ "InYourBassTv Presents Sgt. Pokes (Dour Festival 2008)". Inyourbass.com. 28 August 2008. Retrieved 31 March 2011.

- ^ "Crazy D & Hatcha". Kiss 100 London. Bauer Radio. Archived from the original on August 1, 2008. Retrieved 31 March 2011.

- ^ Gurney, Mark (18 December 2007). "Markle Said Wha?: Plastician Interview (as featured in ATM Magazine Nov 07)". Markleman.blogspot.com. Retrieved 11 November 2009.

- ^ "Rave From the Grave: Skull Disco". The Wire (281). July 2007. ISSN 0952-0686.

- ^ Gilroy, Paul (1987). There Ain't No Black in the Union Jack: The Cultural Politics of Race and Nation. London: Routledge. ISBN 0-415-28981-5.

- ^ Härter, Christoph (22 November 2008). "The Dub Renaissance: Reflections on the Aesthetics of Dub in Contemporary British Music". In Eckstein, Lars; Korte, Barbara; Pirker, Eva Ulrike; Reinfandt, Christoph (eds.). Multi-Ethnic Britain 2000+. New Perspectives in Literature, Film and the Arts. Amsterdam: Rodopi. ISBN 9-042-02497-6.

- ^ a b c d e Mugan, Chris (28 July 2006). "Dubstep: Straight outta Croydon". The Independent. London: Independent Print. Retrieved 1 April 2011.

- ^ a b c Clark, Martin (25 January 2006). "The Month In: Grime/Dubstep". Pitchfork Media. Retrieved 4 July 2007.

- ^ a b Keast, Darren (15 November 2006). "Dawn of Dubstep: Will this Bass-heavy Dance Phenomenon Blow Out Only Your Speakers or Will it Really Blow Up?". SF Weekly. Village Voice Media. Retrieved 2 April 2011.

- ^ a b Warren, Emma (1 August 2007). "The Dubstep Explosion!". DJ Magazine (46): 32.

- ^ Clark, Martin (12 April 2006). "The Month in Grime / Dubstep". Pitchfork Media. Retrieved 2 April 2011.

- ^ "FWD>> Friday 23rd June". Forward>>. June 2006. Archived from the original on 16 June 2006. Retrieved 18 July 2007.

- ^ Fiddy, Chantelle (19 March 2006). "Introducing... Kode 9". Chantelle Fiddy's World of Whatever. Retrieved 3 April 2011.

- ^ Reynolds, Simon (5 March 2009). "Feeling Wonky: Is it Ketamine's Turn to Drive Club Culture?". The Guardian. London: Guardian Media Group. Retrieved 3 April 2011.

- ^ Clark, Martin (22 June 2005). "The Month in Grime / Dubstep". Pitchfork Media. Retrieved 18 July 2007.

- ^ Clark, Martin (20 July 2006). "The Month in Grime / Dubstep". Pitchfork Media. Retrieved 4 July 2007.

- ^ Churchill, Tom (September 2009). "Dmz". Clash. London. Archived from the original on 1 April 2009. Retrieved 3 April 2011.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ Clark, Martin (25 May 2005). "The Month in Grime / Dubstep". Pitchfork Media. Retrieved 18 July 2007.

- ^ a b "About 2 Blow: Dubstep". Rewind Magazine. London. Archived from the original on 7 January 2009. Retrieved 4 April 2011.

- ^ Clark, Martin (8 March 2006). "The Month in Grime / Dubstep". Pitchfork Media. Retrieved 10 July 2007.

- ^ Chan, Sebastian (June 2004). "Various Artists - Grime (Rephlex) / DJ Slimzee - Bingo Beats III (Bingo)". Cyclic Defrost (8). Sydney. ISSN 1832-4835. Retrieved 3 April 2011.

- ^ Chan, Sebastian (January 2005). "Various Artists – Grime 2 (Rephlex)". Cyclic Defrost (10). Sydney. ISSN 1832-4835. Retrieved 3 April 2011.

- ^ Clark, Martin (11 September 2005). "The Month in Grime / Dubstep". Pitchfork Media. Retrieved 17 July 2007.

- ^ Braddock, Kevin (22 February 2004). "Partners in Grime". The Independent. London: Independent Print. Retrieved 3 April 2011.

- ^ Martin, Clark (22 June 2005). "The Month In: Grime / Dubstep". Pitchfork Media. Retrieved 18 July 2007.

- ^ Butler, Nick (19 June 2007). "Burial: Burial". Sputnikmusic. Retrieved 16 July 2007.

- ^ Reynolds, Simon (30 January 2007). "Reasons to Be Cheerful (Just Three)". The Village Voice. Village Voice Media. Retrieved 5 April 2011.

- ^ "Cast and Credits for "Children of Men"". Yahoo! Movies. Yahoo!. Retrieved 19 July 2007.[dead link]

- ^ Chan, Sebastian (November 2006). "Various Artists – The Roots of Dubstep (Tempa)". Cyclic Defrost (15). Sydney. ISSN 1832-4835. Retrieved 5 April 2011.

- ^ "Brand New Heavy". Time Out New York (544). March 2006. ISSN 1084-550X.

- ^ Palermo, Tomas (18 June 2007). "The Week In Dubstep". XLR8R. Archived from the original on 5 April 2011. Retrieved 5 April 2011.

- ^ McBride, Blair (19 March 2010). "Japan's Dubstep Forges Own Path". The Japan Times. Retrieved 5 April 2011.

- ^ Clark, Martin (8 March 2006). "The Month in Grime / Dubstep". Pitchfork Media. Retrieved 5 April 2011.

- ^ Warren, Emma (22 April 2007). "Various, Dubstep Allstars 5 - Mixed By DJ N-Type". The Observer. Guardian Media Group. Retrieved 5 April 2011.

- ^ Finney, Tim (22 June 2008). "Ricardo Villalobos: Vasco EP Part 1". Pitchfork Media. Retrieved 5 April 2011.

- ^ De Young, Nate (19 April 2006). "Ellen Allien & Apparat: Orchestra of Bubbles". Stylus Magazine. Retrieved 14 May 2011.

- ^ Sherburne, Philip (3 May 2006). "Ellen Allien: Orchestra of Dubbles". Pitchfork Media. Retrieved 14 May 2011.

- ^ Wasacz, Walter (11 October 2004). "Losing Your Mind in Berlin". Metro Times. Retrieved 14 May 2011.

- ^ "philip sherburne: November 2005 Archives". Phs.abstractdynamics.org. Retrieved 2011-04-05.

- ^ Blackdown (2007-04-01). "Blackdown: One Friday night". Blackdownsoundboy.blogspot.com. Retrieved 2011-04-05.

- ^ "Pitchfork Feature: Column: The Month in Grime / Dubstep". Pitchforkmedia.com. Retrieved 2011-04-05.

- ^ Porter, Christopher (2008-05-20). "Burial: Beautiful Dread, Inviting and Sinister : NPR Music". Npr.org. Retrieved 2011-04-05.

- ^ Goodman, Steve (2007-11-01). "Kode9 interviews Burial". Hyperdub. Retrieved 2007-11-14.

{{cite news}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help) - ^ "Mary Anne Hobbs - TV". BBC. Retrieved 2009-11-11.

- ^ "Broadcast Yourself". YouTube. Retrieved 2009-11-11.

- ^ "Radio One Hosts Generation Bass « RWD". Rwdmag.com. 2008-08-18. Retrieved 2009-11-11.

- ^ "Generation Bass « n3k4.com". n3k4.com. 2008-08-18. Retrieved 2009-11-11.[dead link]

- ^ Link to Discogs page for Lee "Scratch" Perry, Dubbblestandart, Subatomic Sound System, Prince Far-I "Iron Devil" 12" http://www.discogs.com/Dubblestandart-featuring-Lee-Scratch-Perry-Prince-Far-I-Iron-Devil/release/1554929

- ^ a b c "Women in dubstep - Time Out London". Timeout.com. Retrieved 2011-04-05.

- ^ When We Meet: Issue 24 - Plan B Magazine[dead link]

- ^ Dubstep - Plan B Magazine[dead link]

- ^ Warren, Emma (2008-02-04). "Emma Warren's list of Guardian articles". The Guardian. London. Retrieved 2010-05-01.

- ^ "People<!- Dave generated title ->". Red Bull Music Academy. Retrieved 2011-04-05.

- ^ Decks in the City

- ^ "infinite's Photostream". Flickr. Retrieved 2011-04-05.

- ^ "Collective - Gallery - Dubstep". BBC. Retrieved 2011-04-05.

- ^ Ewing, Tom (2007-11-20). "Column: Poptimist #10: Britney in the Black Lodge (Damn Fine Album)". Pitchfork Media. Retrieved 2007-11-21.

- ^ Segal, Dave (2007-11-06). "Have You Heard of This Britney Spears Chick?". Heard Mentality:The OC Weekly Music Blog. Village Voice Media. Retrieved 2007-11-21.

- ^ "Radio 1 - BBC Radio 1's Chart Show with Reggie Yates - UK Top 40 Dance Singles". BBC. 2007-02-24. Retrieved 2009-11-11.

- ^ Grundy, Gareth (2009-03-15). "Electronic review: La Roux, In For the Kill (Skream remix) | Music | The Observer". London: Guardian. Retrieved 2009-11-11.

- ^ "Freeload: La Roux, "In For The Kill (Skream's Let's Get Ravey Remix) « The FADER". Thefader.com. 2009-04-14. Retrieved 2009-11-11.

- ^ Clark, Martin. "Grime/Dubstep". Pitchfork. Retrieved 2009-11-11.

- ^ "The London Dubstep Scene". Interview Magazine. Retrieved 2009-11-11.

- ^ "Adventures in Modern Music: Issues". The Wire. Retrieved 2009-11-11.

- ^ "XLR8R's Favorites of 2009". XLR8R. Retrieved 2011-04-05.

- ^ Jon Caramanica, "Washes of Sound, Wobbles of Bass," The New York Times September 22, 2009, at p. C5, also found at The New York Times website. Retrieved September 22, 2009.

- ^ "Mutant Funk: Cooly G, Geeneus, and Roska take UK funky and dubstep back to the lab". XLR8R. 2009-09-24. Retrieved 2009-11-11.

- ^ "2009: The Year That Dubstep Broke - Timeline Playlist - New Music Radar - NME.COM - The world's fastest music news service, music videos, interviews, photos and free stuff to win". Nme.Com. Retrieved 2009-11-11.

- ^ Fitzpatrick, Rob (2009-10-11). "Steve Goodman keeps on pioneering". The Times. London.

- ^ Magnetic Man - 'I Need Air' BBC - Chart Blog

- ^ [1] UK Chart: Week Ending 04-Sept-2010

- ^ "Chase & Status - No More Idols". Chart Stats. Retrieved 2011-04-05.

- ^ [2] UK Chart: Week Ending 07-May-2011

- ^ "Dazed Digital | Hank Shocklee". Dazedgroup.com. Retrieved 2009-11-11.

- ^ "Interviews: Chase & Status". M Magazine. PRS for Music. 5 March 2010. Retrieved April 28, 2011.

- ^ Cragg, Michael (2011-01-10). "New music: Britney Spears - Hold It Against Me". The Guardian. London.

- ^ Green, Thomas H (18 November 2009). "Chase & Status Interview". The Daily Telegraph. London: Telegraph Media Group. Retrieved 2 April 2011.

- ^ a b "Dubstep it up - Features, Music". London: The Independent. 2009-04-24. Retrieved 2009-11-11.

- ^ "Alexander Spit". Dubstepped.net. 2009-05-19. Retrieved 2009-11-11.

- ^ "Track Reviews: Eve - "Me N My (Up in the Club)"". Pitchfork. 2009-08-12. Retrieved 2009-11-11.

- ^ "Eve, "Me N My (prod. by Salaam Remi & Benga)" MP3 « The FADER". Thefader.com. Retrieved 2009-11-11.

External links

- GetDarker An online magazine full of interviews, articles, photos from events and videos.

- FilthFM A radio station dedicated to dubstep, grime, and drum and bass sounds.

- BBC Collective dubstep documentary filmed at DMZ 1st Birthday, 2005. Interviews with Mala, Loefah, Skream, Kode9, Youngsta...

- 10 Years of... Dubstep A week dedicated to the movement by Drowned in Sound

- The Month In: Grime/Dubstep Columns by Martin Clark on Pitchfork Media

- This Means War: NYC Dubstep By Flora Fair on Synconation

- Wobble Bass production tutorial by Image-Line Software makers of FL Studio