Faster-than-light

Faster-than-light (also superluminal or FTL) communication and travel refer to the propagation of information or matter faster than the speed of light. The special theory of relativity implies that only particles with zero rest mass may travel at the speed of light. Tachyons, particles whose speed exceeds that of light, have been hypothesized but the existence of such particles would violate causality and the consensus of physicists is that such particles cannot exist.

On the other hand, what some physicists refer to as "apparent" or "effective" FTL[1][2][3][4] depends on the hypothesis that unusually distorted regions of spacetime might permit matter to reach distant locations in less time than light could in normal or undistorted spacetime. According to the current scientific theories, matter is required to travel at subluminally Slower-than-light (also subluminal or STL) speed with respect to the locally distorted spacetime region. Apparent FTL is not excluded by general relativity, however, any Apparent FTL physical plausibility is speculative. Examples of Apparent FTL proposals are the Alcubierre drive and the traversable wormhole.

FTL travel of non-information

In the context of this article, FTL is the transmission of information or matter faster than c, a constant equal to the speed of light in a vacuum, which is 299,792,458 m/s (by definition of the meter) or about 186,282.397 miles per second. This is not quite the same as traveling faster than light, since:

- Some processes propagate faster than c, but cannot carry information (see examples in the sections immediately following).

- Light travels at speed c/n when not in a vacuum but traveling through a medium with refractive index = n (causing refraction), and in some materials other particles can travel faster than c/n (but still slower than c), leading to Cherenkov radiation (see phase velocity below).

Neither of these phenomena violates special relativity or creates problems with causality, and thus neither qualifies as FTL as described here.

In the following examples, certain influences may appear to travel faster than light, but they do not convey energy or information faster than light, so they do not violate special relativity.

Daily sky motion

For an Earthbound observer, objects in the sky complete one revolution around the Earth in 1 day. Proxima Centauri, which is the nearest star outside the solar system, is about 4 light-years away.[5] On a geostationary view, Proxima Centauri has a speed many times greater than c as the rim speed of an object moving in a circle is a product of the radius and angular speed.[5] It is also possible on a geostatic view for objects such as comets to vary their speed from subluminal to superluminal and vice versa simply because the distance from the Earth varies. Comets may have orbits which take them out to more than 1000 AU.[6] The circumference of a circle with a radius of 1000 AU is greater than one light day. In other words, a comet at such a distance is superluminal in a geostatic, and therefore non-inertial, frame.

Light spots and shadows

If a laser beam is swept across a distant object, the spot of laser light can easily be made to move across the object at a speed greater than c.[7] Similarly, a shadow projected onto a distant object can be made to move across the object faster than c.[7] In neither case does the light travel from the source to the object faster than c, nor does any information travel faster than light.[7][8][9]

Apparent FTL propagation of static field effects

Since there is no "retardation" (or aberration) of the apparent position of the source of a gravitational or electric static field when the source moves with constant velocity, the static field "effect" may seem at first glance to be "transmitted" faster than the speed of light. However, uniform motion of the static source may be removed with a change in reference frame, causing the direction of the static field to change immediately, at all distances. This is not a change of position which "propagates", and thus this change cannot be used to transmit information from the source. No information or matter can be FTL-transmitted or propagated from source to receiver/observer by an electromagnetic field.[citation needed]

Closing speeds

The rate at which two objects in motion in a single frame of reference get closer together is called the mutual or closing speed. This may approach twice the speed of light, as in the case of two particles travelling at close to the speed of light in opposite directions with respect to the reference frame.

Imagine two fast-moving particles approaching each other from opposite sides of a particle accelerator of the collider type. The closing speed would be the rate at which the distance between the two particles is decreasing. From the point of view of an observer standing at rest relative to the accelerator, this rate will be slightly less than twice the speed of light.

Special relativity does not prohibit this. It tells us that it is wrong to use Galilean relativity to compute the velocity of one of the particles, as would be measured by an observer traveling alongside the other particle. That is, special relativity gives the right formula for computing such relative velocity.

It is instructive to compute the relative velocity of particles moving at v and −v in accelerator frame, which corresponds to the closing speed of 2v > c. Expressing the speeds in units of c, β = v/c:

Proper speeds

If a spaceship travels to a planet one light-year (as measured in the Earth's rest frame) away from Earth at high speed, the time taken to reach that planet could be less than one year as measured by the traveller's clock (although it will always be more than one year as measured by a clock on Earth). The value obtained by dividing the distance traveled, as determined in the Earth's frame, by the time taken, measured by the traveller's clock, is known as a proper speed or a proper velocity. There is no limit on the value of a proper speed as a proper speed does not represent a speed measured in a single inertial frame. A light signal that left the Earth at the same time as the traveller would always get to the destination before the traveller.

Possible distance away from Earth

Since one might not travel faster than light, one might conclude that a human can never travel further from the Earth than 40 light-years if the traveler is active between the age of 20 and 60. A traveler would then never be able to reach more than the very few star systems which exist within the limit of 20–40 light-years from the Earth. This is a mistaken conclusion: because of time dilation, the traveler can travel thousands of light-years during their 40 active years. If the spaceship accelerates at a constant 1 g (in its own changing frame of reference), it will, after 354 days, reach speeds a little under the speed of light (for an observer on Earth), and time dilation will increase their lifespan to thousands of Earth years, seen from the reference system of the Solar System, but the traveler's subjective lifespan will not thereby change. If the traveler returns to the Earth, she or he will land thousands of years into the Earth's future. Their speed will not be seen as higher than the speed of light by observers on Earth, and the traveler will not measure their speed as being higher than the speed of light, but will see a length contraction of the universe in their direction of travel. And as the traveler turns around to return, the Earth will seem to experience much more time than the traveler does. So, while their (ordinary) coordinate speed cannot exceed c, their proper speed (distance as seen by Earth divided by their proper time) can be much greater than c. This is seen in statistical studies of muons traveling much further than c times their half-life (at rest), if traveling close to c.[10]

Phase velocities above c

The phase velocity of an electromagnetic wave, when traveling through a medium, can routinely exceed c, the vacuum velocity of light. For example, this occurs in most glasses at X-ray frequencies.[11] However, the phase velocity of a wave corresponds to the propagation speed of a theoretical single-frequency (purely monochromatic) component of the wave at that frequency. Such a wave component must be infinite in extent and of constant amplitude (otherwise it is not truly monochromatic), and so cannot convey any information.[12] Thus a phase velocity above c does not imply the propagation of signals with a velocity above c.[13]

Group velocities above c

The group velocity of a wave (e.g., a light beam) may also exceed c in some circumstances.[14][15] In such cases, which typically at the same time involve rapid attenuation of the intensity, the maximum of the envelope of a pulse may travel with a velocity above c. However, even this situation does not imply the propagation of signals with a velocity above c,[16] even though one may be tempted to associate pulse maxima with signals. The latter association has been shown to be misleading, because the information on the arrival of a pulse can be obtained before the pulse maximum arrives. For example, if some mechanism allows the full transmission of the leading part of a pulse while strongly attenuating the pulse maximum and everything behind (distortion), the pulse maximum is effectively shifted forward in time, while the information on the pulse does not come faster than c without this effect.[17] However, group velocity can exceed c in some parts of a Gaussian beam in vacuum (without attenuation). The diffraction causes that the peak of pulse propagates faster, while overall power does not.[18]

Universal expansion

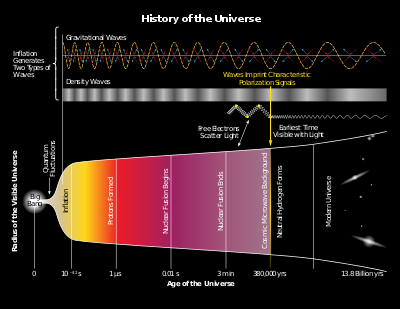

The expansion of the universe causes distant galaxies to recede from us faster than the speed of light, if proper distance and cosmological time are used to calculate the speeds of these galaxies. However, in general relativity, velocity is a local notion, so velocity calculated using comoving coordinates does not have any simple relation to velocity calculated locally.[22] (See comoving distance for a discussion of different notions of 'velocity' in cosmology.) Rules that apply to relative velocities in special relativity, such as the rule that relative velocities cannot increase past the speed of light, do not apply to relative velocities in comoving coordinates, which are often described in terms of the "expansion of space" between galaxies. This expansion rate is thought to have been at its peak during the inflationary epoch thought to have occurred in a tiny fraction of the second after the Big Bang (models suggest the period would have been from around 10−36 seconds after the Big Bang to around 10−33 seconds), when the universe may have rapidly expanded by a factor of around 1020 to 1030.[23]

There are many galaxies visible in telescopes with red shift numbers of 1.4 or higher. All of these are currently traveling away from us at speeds greater than the speed of light. Because the Hubble parameter is decreasing with time, there can actually be cases where a galaxy that is receding from us faster than light does manage to emit a signal which reaches us eventually.[24][25]

According to Tamara M. Davis, "Our effective particle horizon is the cosmic microwave background (CMB), at redshift z ∼ 1100, because we cannot see beyond the surface of last scattering. Although the last scattering surface is not at any fixed comoving coordinate, the current recession velocity of the points from which the CMB was emitted is 3.2c. At the time of emission their speed was 58.1c, assuming (ΩM,ΩΛ) = (0.3,0.7). Thus we routinely observe objects that are receding faster than the speed of light and the Hubble sphere is not a horizon."[26]

However, because the expansion of the universe is accelerating, it is projected that most galaxies will eventually cross a type of cosmological event horizon where any light they emit past that point will never be able to reach us at any time in the infinite future,[27] because the light never reaches a point where its "peculiar velocity" towards us exceeds the expansion velocity away from us (these two notions of velocity are also discussed in Comoving distance#Uses of the proper distance). The current distance to this cosmological event horizon is about 16 billion light-years, meaning that a signal from an event happening at present would eventually be able to reach us in the future if the event was less than 16 billion light-years away, but the signal would never reach us if the event was more than 16 billion light-years away.[25]

Astronomical observations

Apparent superluminal motion is observed in many radio galaxies, blazars, quasars and recently also in microquasars. The effect was predicted before it was observed by Martin Rees[clarification needed] and can be explained as an optical illusion caused by the object partly moving in the direction of the observer,[28] when the speed calculations assume it does not. The phenomenon does not contradict the theory of special relativity. Corrected calculations show these objects have velocities close to the speed of light (relative to our reference frame). They are the first examples of large amounts of mass moving at close to the speed of light.[29] Earth-bound laboratories have only been able to accelerate small numbers of elementary particles to such speeds.

Quantum mechanics

Certain phenomena in quantum mechanics, such as quantum entanglement, might give the superficial impression of allowing communication of information faster than light. According to the no-communication theorem these phenomena do not allow true communication; they only let two observers in different locations see the same system simultaneously, without any way of controlling what either sees. Wavefunction collapse can be viewed as an epiphenomenon of quantum decoherence, which in turn is nothing more than an effect of the underlying local time evolution of the wavefunction of a system and all of its environment. Since the underlying behaviour does not violate local causality or allow FTL it follows that neither does the additional effect of wavefunction collapse, whether real or apparent.

The uncertainty principle implies that individual photons may travel for short distances at speeds somewhat faster (or slower) than c, even in a vacuum; this possibility must be taken into account when enumerating Feynman diagrams for a particle interaction.[30] However, it was shown in 2011 that a single photon may not travel faster than c.[31] In quantum mechanics, virtual particles may travel faster than light, and this phenomenon is related to the fact that static field effects (which are mediated by virtual particles in quantum terms) may travel faster than light (see section on static fields above). However, macroscopically these fluctuations average out, so that photons do travel in straight lines over long (i.e., non-quantum) distances, and they do travel at the speed of light on average. Therefore, this does not imply the possibility of superluminal information transmission.

There have been various reports in the popular press of experiments on faster-than-light transmission in optics — most often in the context of a kind of quantum tunnelling phenomenon. Usually, such reports deal with a phase velocity or group velocity faster than the vacuum velocity of light.[32][33] However, as stated above, a superluminal phase velocity cannot be used for faster-than-light transmission of information.[34][35]

Hartman effect

The Hartman effect is the tunneling effect through a barrier where the tunneling time tends to a constant for large barriers.[36] This was first described by Thomas Hartman in 1962.[37] This could, for instance, be the gap between two prisms. When the prisms are in contact, the light passes straight through, but when there is a gap, the light is refracted. There is a non-zero probability that the photon will tunnel across the gap rather than follow the refracted path. For large gaps between the prisms the tunnelling time approaches a constant and thus the photons appear to have crossed with a superluminal speed.[38]

However, an analysis by Herbert G. Winful from the University of Michigan suggests that the Hartman effect cannot actually be used to violate relativity by transmitting signals faster than c, because the tunnelling time "should not be linked to a velocity since evanescent waves do not propagate".[39] The evanescent waves in the Hartman effect are due to virtual particles and a non-propagating static field, as mentioned in the sections above for gravity and electromagnetism.

Casimir effect

In physics, the Casimir effect or Casimir-Polder force is a physical force exerted between separate objects due to resonance of vacuum energy in the intervening space between the objects. This is sometimes described in terms of virtual particles interacting with the objects, owing to the mathematical form of one possible way of calculating the strength of the effect. Because the strength of the force falls off rapidly with distance, it is only measurable when the distance between the objects is extremely small. Because the effect is due to virtual particles mediating a static field effect, it is subject to the comments about static fields discussed above.

EPR paradox

The EPR paradox refers to a famous thought experiment of Einstein, Podolski and Rosen that was realized experimentally for the first time by Alain Aspect in 1981 and 1982 in the Aspect experiment. In this experiment, the measurement of the state of one of the quantum systems of an entangled pair apparently instantaneously forces the other system (which may be distant) to be measured in the complementary state. However, no information can be transmitted this way; the answer to whether or not the measurement actually affects the other quantum system comes down to which interpretation of quantum mechanics one subscribes to.

An experiment performed in 1997 by Nicolas Gisin at the University of Geneva has demonstrated non-local quantum correlations between particles separated by over 10 kilometers.[40] But as noted earlier, the non-local correlations seen in entanglement cannot actually be used to transmit classical information faster than light, so that relativistic causality is preserved; see no-communication theorem for further information. A 2008 quantum physics experiment also performed by Nicolas Gisin and his colleagues in Geneva, Switzerland has determined that in any hypothetical non-local hidden-variables theory the speed of the quantum non-local connection (what Einstein called "spooky action at a distance") is at least 10,000 times the speed of light.[41]

Delayed choice quantum eraser

Delayed choice quantum eraser (an experiment of Marlan Scully) is a version of the EPR paradox in which the observation or not of interference after the passage of a photon through a double slit experiment depends on the conditions of observation of a second photon entangled with the first. The characteristic of this experiment is that the observation of the second photon can take place at a later time than the observation of the first photon,[42] which may give the impression that the measurement of the later photons "retroactively" determines whether the earlier photons show interference or not, although the interference pattern can only be seen by correlating the measurements of both members of every pair and so it can't be observed until both photons have been measured, ensuring that an experimenter watching only the photons going through the slit does not obtain information about the other photons in an FTL or backwards-in-time manner.[43][44]

Superluminal communication

It has been suggested that Superluminal communication be merged into this article. (Discuss) Proposed since April 2015. |

Faster-than-light communication is, by Einstein's theory of relativity, equivalent to time travel. According to Einstein's theory of special relativity, what we measure as the speed of light in a vacuum (or near vacuum) is actually the fundamental physical constant c. This means that all inertial observers, regardless of their relative velocity, will always measure zero-mass particles such as photons traveling at c in a vacuum. This result means that measurements of time and velocity in different frames are no longer related simply by constant shifts, but are instead related by Poincaré transformations. These transformations have important implications:

- The relativistic momentum of a massive particle would increase with speed in such a way that at the speed of light an object would have infinite momentum.

- To accelerate an object of non-zero rest mass to c would require infinite time with any finite acceleration, or infinite acceleration for a finite amount of time.

- Either way, such acceleration requires infinite energy.

- Some observers with sub-light relative motion will disagree about which occurs first of any two events that are separated by a space-like interval.[45] In other words, any travel that is faster-than-light will be seen as traveling backwards in time in some other, equally valid, frames of reference,[46] or need to assume the speculative hypothesis of possible Lorentz violations at a presently unobserved scale (for instance the Planck scale).[citation needed] Therefore, any theory which permits "true" FTL also has to cope with time travel and all its associated paradoxes,[47] or else to assume the Lorentz invariance to be a symmetry of thermodynamical statistical nature (hence a symmetry broken at some presently unobserved scale).

- In special relativity the coordinate speed of light is only guaranteed to be c in an inertial frame; in a non-inertial frame the coordinate speed may be different from c.[48] In general relativity no coordinate system on a large region of curved spacetime is "inertial", so it's permissible to use a global coordinate system where objects travel faster than c, but in the local neighborhood of any point in curved spacetime we can define a "local inertial frame" and the local speed of light will be c in this frame,[49] with massive objects moving through this local neighborhood always having a speed less than c in the local inertial frame.

Justifications

Faster light (Casimir vacuum and quantum tunnelling)

Einstein's equations of special relativity postulate that the speed of light in a (near) vacuum is invariant in inertial frames. That is, it will be the same from any frame of reference moving at a constant speed. The equations do not specify any particular value for the speed of the light, which is an experimentally determined quantity for a fixed unit of length. Since 1983, the SI unit of length (the meter) has been defined using the speed of light.

The experimental determination has been made in vacuum. However, the vacuum we know is not the only possible vacuum which can exist. The vacuum has energy associated with it, called simply the vacuum energy, which could perhaps be altered in certain cases.[50] When vacuum energy is lowered, light itself has been predicted to go faster than the standard value c. This is known as the Scharnhorst effect. Such a vacuum can be produced by bringing two perfectly smooth metal plates together at near atomic diameter spacing. It is called a Casimir vacuum. Calculations imply that light will go faster in such a vacuum by a minuscule amount: a photon traveling between two plates that are 1 micrometer apart would increase the photon's speed by only about one part in 1036.[51] Accordingly, there has as yet been no experimental verification of the prediction. A recent analysis[52] argued that the Scharnhorst effect cannot be used to send information backwards in time with a single set of plates since the plates' rest frame would define a "preferred frame" for FTL signalling. However, with multiple pairs of plates in motion relative to one another the authors noted that they had no arguments that could "guarantee the total absence of causality violations", and invoked Hawking's speculative chronology protection conjecture which suggests that feedback loops of virtual particles would create "uncontrollable singularities in the renormalized quantum stress-energy" on the boundary of any potential time machine, and thus would require a theory of quantum gravity to fully analyze. Other authors argue that Scharnhorst's original analysis, which seemed to show the possibility of faster-than-c signals, involved approximations which may be incorrect, so that it is not clear whether this effect could actually increase signal speed at all.[53]

The physicists Günter Nimtz and Alfons Stahlhofen, of the University of Cologne, claim to have violated relativity experimentally by transmitting photons faster than the speed of light.[38] They say they have conducted an experiment in which microwave photons — relatively low-energy packets of light — travelled "instantaneously" between a pair of prisms that had been moved up to 3 ft (1 m) apart. Their experiment involved an optical phenomenon known as "evanescent modes", and they claim that since evanescent modes have an imaginary wave number, they represent a "mathematical analogy" to quantum tunnelling.[38] Nimtz has also claimed that "evanescent modes are not fully describable by the Maxwell equations and quantum mechanics have to be taken into consideration."[54] Other scientists such as Herbert G. Winful and Robert Helling have argued that in fact there is nothing quantum-mechanical about Nimtz's experiments, and that the results can be fully predicted by the equations of classical electromagnetism (Maxwell's equations).[55][56]

Nimtz told New Scientist magazine: "For the time being, this is the only violation of special relativity that I know of." However, other physicists say that this phenomenon does not allow information to be transmitted faster than light. Aephraim Steinberg, a quantum optics expert at the University of Toronto, Canada, uses the analogy of a train traveling from Chicago to New York, but dropping off train cars at each station along the way, so that the center of the ever-shrinking main train moves forward at each stop; in this way, the speed of the center of the train exceeds the speed of any of the individual cars.[57]

Herbert G. Winful argues that the train analogy is a variant of the "reshaping argument" for superluminal tunneling velocities, but he goes on to say that this argument is not actually supported by experiment or simulations, which actually show that the transmitted pulse has the same length and shape as the incident pulse.[55] Instead, Winful argues that the group delay in tunneling is not actually the transit time for the pulse (whose spatial length must be greater than the barrier length in order for its spectrum to be narrow enough to allow tunneling), but is instead the lifetime of the energy stored in a standing wave which forms inside the barrier. Since the stored energy in the barrier is less than the energy stored in a barrier-free region of the same length due to destructive interference, the group delay for the energy to escape the barrier region is shorter than it would be in free space, which according to Winful is the explanation for apparently superluminal tunneling.[58][59]

A number of authors have published papers disputing Nimtz's claim that Einstein causality is violated by his experiments, and there are many other papers in the literature discussing why quantum tunneling is not thought to violate causality.[60]

It was later claimed by the Keller group in Switzerland that particle tunneling does indeed occur in zero real time. Their tests involved tunneling electrons, where the group argued a relativistic prediction for tunneling time should be 500-600 attoseconds (an attosecond is one quintillionth (10−18) of a second). All that could be measured was 24 attoseconds, which is the limit of the test accuracy.[61] Again, though, other physicists believe that tunneling experiments in which particles appear to spend anomalously short times inside the barrier are in fact fully compatible with relativity, although there is disagreement about whether the explanation involves reshaping of the wave packet or other effects.[58][59][62]

Give up (absolute) relativity

Because of the strong empirical support for special relativity, any modifications to it must necessarily be quite subtle and difficult to measure. The best-known attempt is doubly special relativity, which posits that the Planck length is also the same in all reference frames, and is associated with the work of Giovanni Amelino-Camelia and João Magueijo.

There are speculative theories that claim inertia is produced by the combined mass of the universe (e.g., Mach's principle), which implies that the rest frame of the universe might be preferred by conventional measurements of natural law. If confirmed, this would imply special relativity is an approximation to a more general theory, but since the relevant comparison would (by definition) be outside the observable universe, it is difficult to imagine (much less construct) experiments to test this hypothesis.

Spacetime distortion

Although the theory of special relativity forbids objects to have a relative velocity greater than light speed, and general relativity reduces to special relativity in a local sense (in small regions of spacetime where curvature is negligible), general relativity does allow the space between distant objects to expand in such a way that they have a "recession velocity" which exceeds the speed of light, and it is thought that galaxies which are at a distance of more than about 14 billion light-years from us today have a recession velocity which is faster than light.[63] Miguel Alcubierre theorized that it would be possible to create an Alcubierre drive, in which a ship would be enclosed in a "warp bubble" where the space at the front of the bubble is rapidly contracting and the space at the back is rapidly expanding, with the result that the bubble can reach a distant destination much faster than a light beam moving outside the bubble, but without objects inside the bubble locally traveling faster than light. However, several objections raised against the Alcubierre drive appear to rule out the possibility of actually using it in any practical fashion. Another possibility predicted by general relativity is the traversable wormhole, which could create a shortcut between arbitrarily distant points in space. As with the Alcubierre drive, travelers moving through the wormhole would not locally move faster than light travelling through the wormhole alongside them, but they would be able to reach their destination (and return to their starting location) faster than light traveling outside the wormhole.

Dr. Gerald Cleaver, associate professor of physics at Baylor University, and Richard Obousy, a Baylor graduate student, theorized that manipulating the extra spatial dimensions of string theory around a spaceship with an extremely large amount of energy would create a "bubble" that could cause the ship to travel faster than the speed of light. To create this bubble, the physicists believe manipulating the 10th spatial dimension would alter the dark energy in three large spatial dimensions: height, width and length. Cleaver said positive dark energy is currently responsible for speeding up the expansion rate of our universe as time moves on.[64]

Heim theory

In 1977, a paper on Heim theory theorized that it may be possible to travel faster than light by using magnetic fields to enter a higher-dimensional space.[65]

Lorentz symmetry violation

The possibility that Lorentz symmetry may be violated has been seriously considered in the last two decades, particularly after the development of a realistic effective field theory that describes this possible violation, the so-called Standard-Model Extension.[66][67][68] This general framework has allowed experimental searches by ultra-high energy cosmic-ray experiments[69] and a wide variety of experiments in gravity, electrons, protons, neutrons, neutrinos, mesons, and photons.[70] The breaking of rotation and boost invariance causes direction dependence in the theory as well as unconventional energy dependence that introduces novel effects, including Lorentz-violating neutrino oscillations and modifications to the dispersion relations of different particle species, which naturally could make particles move faster than light.

In some models of broken Lorentz symmetry, it is postulated that the symmetry is still built into the most fundamental laws of physics, but that spontaneous symmetry breaking of Lorentz invariance[71] shortly after the Big Bang could have left a "relic field" throughout the universe which causes particles to behave differently depending on their velocity relative to the field;[72] however, there are also some models where Lorentz symmetry is broken in a more fundamental way. If Lorentz symmetry can cease to be a fundamental symmetry at Planck scale or at some other fundamental scale, it is conceivable that particles with a critical speed different from the speed of light be the ultimate constituents of matter.

In current models of Lorentz symmetry violation, the phenomenological parameters are expected to be energy-dependent. Therefore, as widely recognized,[73][74] existing low-energy bounds cannot be applied to high-energy phenomena; however, many searches for Lorentz violation at high energies have been carried out using the Standard-Model Extension.[70] Lorentz symmetry violation is expected to become stronger as one gets closer to the fundamental scale.

Superfluid theories of physical vacuum

In this approach the physical vacuum is viewed as the quantum superfluid which is essentially non-relativistic whereas the Lorentz symmetry is not an exact symmetry of nature but rather the approximate description valid only for the small fluctuations of the superfluid background.[75] Within the framework of the approach a theory was proposed in which the physical vacuum is conjectured to be the quantum Bose liquid whose ground-state wavefunction is described by the logarithmic Schrödinger equation. It was shown that the relativistic gravitational interaction arises as the small-amplitude collective excitation mode[76] whereas relativistic elementary particles can be described by the particle-like modes in the limit of low momenta.[77] The important fact is that at very high velocities the behavior of the particle-like modes becomes distinct from the relativistic one - they can reach the speed of light limit at finite energy; also, faster-than-light propagation is possible without requiring moving objects to have imaginary mass.[78][79]

Time of flight of neutrinos

MINOS experiment

In 2007 the MINOS collaboration reported results measuring the flight-time of 3 GeV neutrinos yielding a speed exceeding that of light by 1.8-sigma significance.[80] However, those measurements were considered to be statistically consistent with neutrinos traveling at the speed of light.[81] After the detectors for the project were upgraded in 2012, MINOS corrected their initial result and found agreement with the speed of light. Further measurements are going to be conducted.[82]

OPERA neutrino anomaly

On September 22, 2011, a preprint[83] from the OPERA Collaboration indicated detection of 17 and 28 GeV muon neutrinos, sent 730 kilometers (454 miles) from CERN near Geneva, Switzerland to the Gran Sasso National Laboratory in Italy, traveling faster than light by a relative amount of 2.48×10−5 (approximately 1 in 40,000), a statistic with 6.0-sigma significance.[84] On 17 November 2011, a second follow-up experiment by OPERA scientists confirmed their initial results.[85][86] However, scientists were skeptical about the results of these experiments, the significance of which was disputed.[87] In March 2012, the ICARUS collaboration failed to reproduce the OPERA results with their equipment, detecting neutrino travel time from CERN to the Gran Sasso National Laboratory indistinguishable from the speed of light.[88] Later the OPERA team reported two flaws in their equipment set-up that had caused errors far outside their original confidence interval: a fiber optic cable attached improperly, which caused the apparently faster-than-light measurements, and a clock oscillator ticking too fast.[89]

Tachyons

In special relativity, it is impossible to accelerate an object to the speed of light, or for a massive object to move at the speed of light. However, it might be possible for an object to exist which always moves faster than light. The hypothetical elementary particles with this property are called tachyonic particles. Attempts to quantize them failed to produce faster-than-light particles, and instead illustrated that their presence leads to an instability.[90][91]

Various theorists have suggested that the neutrino might have a tachyonic nature,[92][93][94][95] while others have disputed the possibility.[96]

Exotic matter

Mechanical equations to describe hypothetical exotic matter which possesses a negative mass, negative momentum, negative pressure and negative kinetic energy are [97]

- ,

Considering and , the energy-momentum relation of the particle is corresponding to the following dispersion relation

- ,

of a wave that can propagate in the negative index metamaterial. Interestingly, the pressure of radiation pressure in the metamaterial is negative[98] and negative refraction, inverse Doppler effect and reverse Cherenkov effect imply that the momentum is also negative. So the wave in a negative index metamaterial can be applied to test the theory of exotic matter and negative mass. For example, the velocity equals

- ,

- ,

That is to say, such a wave can break the light barrier under certain conditions and the correctness of the prediction can be judged by comparison with experiments.

General relativity

General relativity was developed after special relativity to include concepts like gravity. It maintains the principle that no object can accelerate to the speed of light in the reference frame of any coincident observer.[citation needed][clarification needed] However, it permits distortions in spacetime that allow an object to move faster than light from the point of view of a distant observer.[citation needed][clarification needed] One such distortion is the Alcubierre drive, which can be thought of as producing a ripple in spacetime that carries an object along with it. Another possible system is the wormhole, which connects two distant locations as though by a shortcut. Both distortions would need to create a very strong curvature in a highly localized region of space-time and their gravity fields would be immense. To counteract the unstable nature, and prevent the distortions from collapsing under their own 'weight', one would need to introduce hypothetical exotic matter or negative energy.

General relativity also recognizes that any means of faster-than-light travel could also be used for time travel. This raises problems with causality. Many physicists believe that the above phenomena are impossible and that future theories of gravity will prohibit them. One theory states that stable wormholes are possible, but that any attempt to use a network of wormholes to violate causality would result in their decay.[citation needed] In string theory, Eric G. Gimon and Petr Hořava have argued[99] that in a supersymmetric five-dimensional Gödel universe, quantum corrections to general relativity effectively cut off regions of spacetime with causality-violating closed timelike curves. In particular, in the quantum theory a smeared supertube is present that cuts the spacetime in such a way that, although in the full spacetime a closed timelike curve passed through every point, no complete curves exist on the interior region bounded by the tube.

Variable speed of light

In physics, the speed of light in a vacuum is assumed to be a constant. However, hypotheses exist that the speed of light is variable.

The speed of light is a dimensional quantity and so, as has been emphasized in this context by João Magueijo, it cannot be measured.[100] Measurable quantities in physics are, without exception, dimensionless, although they are often constructed as ratios of dimensional quantities. For example, when the height of a mountain is measured, what is really measured is the ratio of its height to the length of a meter stick. The conventional SI system of units is based on seven basic dimensional quantities, namely distance, mass, time, electric current, thermodynamic temperature, amount of substance, and luminous intensity.[101] These units are defined to be independent and so cannot be described in terms of each other. As an alternative to using a particular system of units, one can reduce all measurements to dimensionless quantities expressed in terms of ratios between the quantities being measured and various fundamental constants such as Newton's constant, the speed of light and Planck's constant; physicists can define at least 26 dimensionless constants which can be expressed in terms of these sorts of ratios and which are currently thought to be independent of one another.[102] By manipulating the basic dimensional constants one can also construct the Planck time, Planck length and Planck energy which make a good system of units for expressing dimensional measurements, known as Planck units.

Magueijo's proposal used a different set of units, a choice which he justifies with the claim that some equations will be simpler in these new units. In the new units he fixes the fine structure constant, a quantity which some people, using units in which the speed of light is fixed, have claimed is time-dependent. Thus in the system of units in which the fine structure constant is fixed, the observational claim is that the speed of light is time-dependent.

See also

- Alcubierre drive

- Faster-than-light neutrino anomaly

- Intergalactic travel

- Krasnikov tube

- Superluminal motion, apparent faster-than-light motion

- Tachyon

- Tachyonic field

- Wheeler–Feynman absorber theory

- Animorphs (Zero Space)

- Ansible

- Battlestar (reimagining)

- FTL engine (Eureka)

- FTL drive (Battlestar Galactica)

- FTL: Faster Than Light

- FTL:2448 by Tri Tac Games

- Hyperdrive

- Hyperspace

- Inertialess drive

- Infinite Improbability Drive

- Jump drive

- Jumpgate

- Kearny-Fuchida jump drive (BattleTech)

- Macross Space Fold

- Mass Effect Relay

- Skip drive

- Slipstream (science fiction)

- Starburst (Farscape)

- Stargate (device)

- Interdimensional Drive (Earth Final Conflict)

- TARDIS (Doctor Who)

- Ultrawave

- Warp drive

Notes

- ^ Gonzalez-Diaz, P. F. (2000). "Warp drive space-time" (PDF). Physical Review D. 62 (4): 044005. arXiv:gr-qc/9907026. Bibcode:2000PhRvD..62d4005G. doi:10.1103/PhysRevD.62.044005.

- ^ Loup, F.; Waite, D.; Halerewicz, E. Jr. (2001). "Reduced total energy requirements for a modified Alcubierre warp drive spacetime". arXiv:gr-qc/0107097.

- ^ Visser, M.; Bassett, B.; Liberati, S. (2000). "Superluminal censorship". Nuclear Physics B: Proceedings Supplement. 88: 267–270. arXiv:gr-qc/9810026. Bibcode:2000NuPhS..88..267V. doi:10.1016/S0920-5632(00)00782-9.

- ^ Visser, M.; Bassett, B.; Liberati, S. (1999). "Perturbative superluminal censorship and the null energy condition". AIP Conference Proceedings. 493: 301–305. arXiv:gr-qc/9908023. Bibcode:1999AIPC..493..301V. doi:10.1063/1.1301601. ISBN 1-56396-905-X.

- ^ a b University of York Science Education Group (2001). Salter Horners Advanced Physics A2 Student Book. Heinemann. pp. 302–303. ISBN 978-0435628925.

- ^ "The Furthest Object in the Solar System". Information Leaflet No. 55. Royal Greenwich Observatory. 15 April 1996.

- ^ a b c Gibbs, P. (1997). "Is Faster-Than-Light Travel or Communication Possible?". The Original Usenet Physics FAQ. Retrieved 20 August 2008.

- ^ Salmon, W. C. (2006). Four Decades of Scientific Explanation. University of Pittsburgh Press. p. 107. ISBN 0-8229-5926-7.

- ^ Steane, A. (2012). The Wonderful World of Relativity: A Precise Guide for the General Reader. Oxford University Press. p. 180. ISBN 0-19-969461-3.

- ^ Sartori, L. (1976). Understanding Relativity: A Simplified Approach to Einstein's Theories. University of California Press. pp. 79–83. ISBN 978-0-520-91624-1.

- ^ Hecht, E. (1987). Optics (2nd ed.). Addison Wesley. p. 62. ISBN 0-201-11609-X.

- ^ Sommerfeld, A. (1907). . Physikalische Zeitschrift. 8 (23): 841–842.

- ^ "Phase, Group, and Signal Velocity". MathPages. Retrieved 2007-04-30.

- ^ Wang, L. J.; Kuzmich, A.; Dogariu, A. (2000). "Gain-assisted superluminal light propagation". Nature. 406 (6793): 277–279. doi:10.1038/35018520.

- ^ Bowlan, P.; Valtna-Lukner, H.; Lõhmus, M.; Piksarv, P.; Saari, P.; Trebino, R. (2009). "Measurement of the spatiotemporal electric field of ultrashort superluminal Bessel-X pulses". Optics and Photonics News. 20 (12): 42. Bibcode:2009OptPN..20...42M. doi:10.1364/OPN.20.12.000042.

- ^ Brillouin, L (1960). Wave Propagation and Group Velocity. Academic Press.

- ^ Withayachumnankul, W.; Fischer, B. M.; Ferguson, B.; Davis, B. R.; Abbott, D. (2010). "A Systemized View of Superluminal Wave Propagation" (PDF). Proceedings of the IEEE. 98 (10): 1775–1786. doi:10.1109/JPROC.2010.2052910.

- ^ Horváth, Z. L.; Vinkó, J.; Bor, Zs.; von der Linde, D. (1996). "Acceleration of femtosecond pulses to superluminal velocities by Gouy phase shift" (PDF). Applied Physics B. 63 (5): 481–484. Bibcode:1996ApPhB..63..481H. doi:10.1007/BF01828944.

- ^

"BICEP2 2014 Results Release". BICEP2. 17 March 2014. Retrieved 18 March 2014.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|authors=ignored (help) - ^ Clavin, W. (17 March 2014). "NASA Technology Views Birth of the Universe". Jet Propulsion Lab. Retrieved 17 March 2014.

- ^ Overbye, D. (17 March 2014). "Detection of Waves in Space Buttresses Landmark Theory of Big Bang". New York Times. Retrieved 17 March 2014.

- ^ Wright, E. L. (12 June 2009). "Cosmology Tutorial - Part 2". Ned Wright's Cosmology Tutorial. UCLA. Retrieved 2011-09-26.

- ^ Nave, R. "Inflationary Period". HyperPhysics. Retrieved 2011-09-26.

- ^ See the last two paragraphs in Rothstein, D. (10 September 2003). "Is the universe expanding faster than the speed of light?". Ask an Astronomer.

- ^ a b

Lineweaver, C.; Davis, T. M. (March 2005). "Misconceptions about the Big Bang" (PDF). Scientific American. pp. 36–45. Retrieved 2008-11-06.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: year (link) - ^ Davis, T. M.; Lineweaver, C. H. (2004). "Expanding Confusion:common misconceptions of cosmological horizons and the superluminal expansion of the universe". Publications of the Astronomical Society of Australia. 21 (1): 97–109. arXiv:astro-ph/0310808. Bibcode:2004PASA...21...97D. doi:10.1071/AS03040.

- ^ Loeb, A. (2002). "The Long-Term Future of Extragalactic Astronomy". Physical Review D. 65 (4): 047301. arXiv:astro-ph/0107568. Bibcode:2002PhRvD..65d7301L. doi:10.1103/PhysRevD.65.047301.

- ^ Rees, M. J. (1966). "Appearance of relativistically expanding radio sources". Nature. 211 (5048): 468–470. Bibcode:1966Natur.211..468R. doi:10.1038/211468a0.

- ^ Blandford, R. D.; McKee, C. F.; Rees, M. J. (1977). "Super-luminal expansion in extragalactic radio sources". Nature. 267 (5608): 211–216. Bibcode:1977Natur.267..211B. doi:10.1038/267211a0.

- ^ Grozin, A. (2007). Lectures on QED and QCD. World Scientific. p. 89. ISBN 981-256-914-6.

- ^ Zhang, S.; Chen, J. F.; Liu, C.; Loy, M. M. T.; Wong, G. K. L.; Du, S. (2011). "Optical Precursor of a Single Photon". Physical Review Letters. 106 (24): 243602. Bibcode:2011PhRvL.106x3602Z. doi:10.1103/PhysRevLett.106.243602.

- ^ Kåhre, J. (2012). The Mathematical Theory of Information (Illustrated ed.). Springer Science & Business Media. p. 425. ISBN 978-1-4615-0975-2.

- ^ Steinberg, A. M. (1994). When Can Light Go Faster Than Light? (Thesis). University of California, Berkeley. p. 100. Bibcode:1994PhDT.......314S.

- ^ Chubb, J.; Eskandarian, A.; Harizanov, V. (2016). Logic and Algebraic Structures in Quantum Computing (Illustrated ed.). Cambridge University Press. p. 61. ISBN 978-1-107-03339-9.

- ^ Ehlers, J.; Lämmerzahl, C. (2006). Special Relativity: Will it Survive the Next 101 Years? (Illustrated ed.). Springer. p. 506. ISBN 978-3-540-34523-7.

- ^ Martinez, J. C.; Polatdemir, E. (2006). "Origin of the Hartman effect". Physics Letters A. 351 (1–2): 31–36. Bibcode:2006PhLA..351...31M. doi:10.1016/j.physleta.2005.10.076.

- ^ Hartman, T. E. (1962). "Tunneling of a Wave Packet". Journal of Applied Physics. 33 (12): 3427–3433. Bibcode:1962JAP....33.3427H. doi:10.1063/1.1702424.

- ^ a b c Nimtz, Günter; Stahlhofen, Alfons (2007). "Macroscopic violation of special relativity". arXiv:0708.0681 [quant-ph].

- ^ Winful, H. G. (2006). "Tunneling time, the Hartman effect, and superluminality: A proposed resolution of an old paradox". Physics Reports. 436 (1–2): 1–69. Bibcode:2006PhR...436....1W. doi:10.1016/j.physrep.2006.09.002.

- ^ Suarez, A. (26 February 2015). "History". Center for Quantum Philosophy. Retrieved 2017-06-07.

- ^ Salart, D.; Baas, A.; Branciard, C.; Gisin, N.; Zbinden, H. (2008). "Testing spooky action at a distance". Nature. 454 (7206): 861–864. arXiv:0808.3316. Bibcode:2008Natur.454..861S. doi:10.1038/nature07121. PMID 18704081.

- ^ Kim, Yoon-Ho; Yu, Rong; Kulik, Sergei P.; Shih, Yanhua; Scully, Marlan O. (2000). "Delayed "Choice" Quantum Eraser". Physical Review Letters. 84 (1): 1–5. arXiv:quant-ph/9903047. Bibcode:2000PhRvL..84....1K. doi:10.1103/PhysRevLett.84.1.

- ^ Hillmer, R.; Kwiat, P. (16 April 2017). "Delayed-Choice Experiments". Scientific American.

- ^ Motl, L. (November 2010). "Delayed choice quantum eraser". The Reference Frame.

- ^ Einstein, A. (1927). Relativity:the special and the general theory. Methuen & Co. pp. 25–27.

- ^ Odenwald, S. "If we could travel faster than light, could we go back in time?". NASA Astronomy Café. Retrieved 7 April 2014.

- ^ Gott, J. R. (2002). Time Travel in Einstein's Universe. Mariner Books. pp. 82–83. ISBN 978-0618257355.

- ^ Petkov, V. (2009). Relativity and the Nature of Spacetime. Springer Science & Business Media. p. 219. ISBN 978-3642019623.

- ^ Raine, D. J.; Thomas, E. G. (2001). An Introduction to the Science of Cosmology. CRC Press. p. 94. ISBN 978-0750304054.

- ^ "What is the 'zero-point energy' (or 'vacuum energy') in quantum physics? Is it really possible that we could harness this energy?". Scientific American. 1997-08-18. Retrieved 2009-05-27.

- ^ Scharnhorst, Klaus (1990-05-12). "Secret of the vacuum: Speedier light". Retrieved 2009-05-27.

- ^ Visser, Matt; Liberati, Stefano; Sonego, Sebastiano (2001-07-27). "Faster-than-c signals, special relativity, and causality". Annals of Physics. 298: 167–185. arXiv:gr-qc/0107091. Bibcode:2002AnPhy.298..167L. doi:10.1006/aphy.2002.6233.

- ^ Fearn, Heidi (2007). "Can Light Signals Travel Faster than c in Nontrivial Vacuua in Flat space-time? Relativistic Causality II". LaserPhys. 17 (5): 695–699. arXiv:0706.0553. Bibcode:2007LaPhy..17..695F. doi:10.1134/S1054660X07050155.

- ^ Nimtz, G (2001). "Superluminal Tunneling Devices". arXiv:physics/0204043.

- ^ a b Winful, Herbert G. (2007-09-18). "Comment on "Macroscopic violation of special relativity" by Nimtz and Stahlhofen". arXiv:0709.2736 [quant-ph].

- ^ Helling, R. (20 September 2005). "Faster than light or not". atdotde.blogspot.ca.

- ^ Anderson, Mark (18–24 August 2007). "Light seems to defy its own speed limit". New Scientist. Vol. 195, no. 2617. p. 10.

- ^ a b Winful, Herbert G. (December 2006). "Tunneling time, the Hartman effect, and superluminality: A proposed resolution of an old paradox" (PDF). Physics Reports. 436 (1–2): 1–69. Bibcode:2006PhR...436....1W. doi:10.1016/j.physrep.2006.09.002.

- ^ a b For a summary of Herbert G. Winful's explanation for apparently superluminal tunneling time which does not involve reshaping, see Winful, Herbert (2007). "New paradigm resolves old paradox of faster-than-light tunneling". SPIE Newsroom. doi:10.1117/2.1200711.0927.

- ^ A number of papers are listed at Literature on Faster-than-light tunneling experiments

- ^ Eckle, P.; Pfeiffer, A. N.; Cirelli, C.; Staudte, A.; Dorner, R.; Muller, H. G.; Buttiker, M.; Keller, U. (5 December 2008). "Attosecond Ionization and Tunneling Delay Time Measurements in Helium". Science. 322 (5907): 1525–1529. doi:10.1126/science.1163439.

- ^ Sokolovski, D. (8 February 2004). "Why does relativity allow quantum tunneling to 'take no time'?" (PDF). Proceedings of the Royal Society A. 460 (2042): 499–506. Bibcode:2004RSPSA.460..499S. doi:10.1098/rspa.2003.1222.

- ^ Lineweaver, Charles H.; Davis, Tamara M. (March 2005). "Misconceptions about the Big Bang". Scientific American.

- ^ Traveling Faster Than the Speed of Light: A New Idea That Could Make It Happen Newswise, retrieved on 24 August 2008.

- ^ Heim, Burkhard (1977). "Vorschlag eines Weges einer einheitlichen Beschreibung der Elementarteilchen [Recommendation of a Way to a Unified Description of Elementary Particles]". Zeitschrift für Naturforschung. 32a: 233–243. Bibcode:1977ZNatA..32..233H. doi:10.1515/zna-1977-3-404.

- ^ Colladay, Don; Kostelecký, V. Alan (1997). "CPT violation and the standard model". Physical Review D. 55 (11): 6760–6774. arXiv:hep-ph/9703464. Bibcode:1997PhRvD..55.6760C. doi:10.1103/PhysRevD.55.6760.

- ^ Colladay, Don; Kostelecký, V. Alan (1998). "Lorentz-violating extension of the standard model". Physical Review D. 58 (11). arXiv:hep-ph/9809521. Bibcode:1998PhRvD..58k6002C. doi:10.1103/PhysRevD.58.116002.

- ^ Kostelecký, V. Alan (2004). "Gravity, Lorentz violation, and the standard model". Physical Review D. 69 (10). arXiv:hep-th/0312310. Bibcode:2004PhRvD..69j5009K. doi:10.1103/PhysRevD.69.105009.

- ^ Gonzalez-Mestres, Luis (2009). "AUGER-HiRes results and models of Lorentz symmetry violation". Nuclear Physics B: Proceedings Supplements. 190: 191–197. arXiv:0902.0994. Bibcode:2009NuPhS.190..191G. doi:10.1016/j.nuclphysbps.2009.03.088.

- ^ a b Kostelecký, V. Alan; Russell, Neil (2011). "Data tables for Lorentz and CPT violation". Reviews of Modern Physics. 83: 11–31. arXiv:0801.0287. Bibcode:2011RvMP...83...11K. doi:10.1103/RevModPhys.83.11.

- ^ Kostelecký, V. A.; Samuel, S. (15 January 1989). "Spontaneous breaking of Lorentz symmetry in string theory". Physical Review D. 39 (2): 683–685. doi:10.1103/PhysRevD.39.683.

- ^ "PhysicsWeb - Breaking Lorentz symmetry". Web.archive.org. 2004-04-05. Archived from the original on 2004-04-05. Retrieved 2011-09-26.

- ^ Mavromatos, Nick E.; Testing models for quantum gravity, CERN Courier, http://cerncourier.com/cws/article/cern/28696 (August 2002)

- ^ Overbye, Dennis; Interpreting the Cosmic Rays, The New York Times, 31 December 2002

- ^ Volovik, G. E. (2003). "The Universe in a helium droplet". International Series of Monographs on Physics. 117: 1–507.

- ^ Zloshchastiev, Konstantin G. (2009). "Spontaneous symmetry breaking and mass generation as built-in phenomena in logarithmic nonlinear quantum theory". Acta Physica Polonica B. 42 (2): 261–292. arXiv:0912.4139. Bibcode:2011AcPPB..42..261Z. doi:10.5506/APhysPolB.42.261.

- ^ Avdeenkov, Alexander V.; Zloshchastiev, Konstantin G. (2011). "Quantum Bose liquids with logarithmic nonlinearity: Self-sustainability and emergence of spatial extent". Journal of Physics B: Atomic, Molecular and Optical Physics. 44 (19): 195303. arXiv:1108.0847. Bibcode:2011JPhB...44s5303A. doi:10.1088/0953-4075/44/19/195303.

- ^ Zloshchastiev, Konstantin G.; Chakrabarti, Sandip K.; Zhuk, Alexander I.; Bisnovatyi-Kogan, Gennady S. (2010). "Logarithmic nonlinearity in theories of quantum gravity: Origin of time and observational consequences". AIP Conference Proceedings: 112. arXiv:0906.4282. Bibcode:2010AIPC.1206..112Z. doi:10.1063/1.3292518.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - ^ Zloshchastiev, Konstantin G. (2011). "Vacuum Cherenkov effect in logarithmic nonlinear quantum theory". Physics Letters A. 375 (24): 2305–2308. arXiv:1003.0657. Bibcode:2011PhLA..375.2305Z. doi:10.1016/j.physleta.2011.05.012.

- ^ Adamson, P.; Andreopoulos, C.; Arms, K.; Armstrong, R.; Auty, D.; Avvakumov, S.; Ayres, D.; Baller, B.; Barish, B. (2007). "Measurement of neutrino velocity with the MINOS detectors and NuMI neutrino beam". Physical Review D. 76 (7). arXiv:0706.0437. Bibcode:2007PhRvD..76g2005A. doi:10.1103/PhysRevD.76.072005.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|displayauthors=ignored (|display-authors=suggested) (help) - ^ Overbye, Dennis (22 September 2011). "Tiny neutrinos may have broken cosmic speed limit". New York Times.

That group found, although with less precision, that the neutrino speeds were consistent with the speed of light.

- ^ "MINOS reports new measurement of neutrino velocity". Fermilab today. June 8, 2012. Retrieved June 8, 2012.

- ^ Adam, T.; et al. (OPERA Collaboration) (22 September 2011). "Measurement of the neutrino velocity with the OPERA detector in the CNGS beam". arXiv:1109.4897v1.

- ^ Cho, Adrian; Neutrinos Travel Faster Than Light, According to One Experiment, Science NOW, 22 September 2011

- ^ Overbye, Dennis (18 November 2011). "Scientists Report Second Sighting of Faster-Than-Light Neutrinos". New York Times. Retrieved 2011-11-18.

- ^ Adam, T.; et al. (OPERA Collaboration) (17 November 2011). "Measurement of the neutrino velocity with the OPERA detector in the CNGS beam". arXiv:1109.4897v2.

- ^ Reuters: Study rejects "faster than light" particle finding

- ^ Antonello, M.; et al. (ICARUS Collaboration) (15 March 2012). "Measurement of the neutrino velocity with the ICARUS detector at the CNGS beam". arXiv:1203.3433.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - ^ Strassler, M. (2012) "OPERA: What Went Wrong" profmattstrassler.com

- ^ Randall, Lisa; Warped Passages: Unraveling the Mysteries of the Universe's Hidden Dimensions, p. 286: "People initially thought of tachyons as particles travelling faster than the speed of light...But we now know that a tachyon indicates an instability in a theory that contains it. Regrettably for science fiction fans, tachyons are not real physical particles that appear in nature."

- ^ Gates, S. James. "Superstring Theory: The DNA of Reality".

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - ^ Chodos, A.; Hauser, A. I.; Alan Kostelecký, V. (1985). "The neutrino as a tachyon". Physics Letters B. 150 (6): 431–435. doi:10.1016/0370-2693(85)90460-5.

- ^ Chodos, Alan; Kostelecký, V. Alan; IUHET 280 (1994). "Nuclear Null Tests for Spacelike Neutrinos". Physics Letters B. 336 (3–4): 295–302. arXiv:hep-ph/9409404. Bibcode:1994PhLB..336..295C. doi:10.1016/0370-2693(94)90535-5.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) - ^ Chodos, A.; Kostelecký, V. A.; Potting, R.; Gates, Evalyn (1992). "Null experiments for neutrino masses". Modern Physics Letters A. 7 (6): 467–476. doi:10.1142/S0217732392000422.

- ^ Chang, Tsao (2002). "Parity Violation and Neutrino Mass". Nuclear Science and Techniques. 13: 129–133. arXiv:hep-ph/0208239.

- ^ Hughes, R. J.; Stephenson, G. J. (1990). "Against tachyonic neutrinos". Physics Letters B. 244 (1): 95–100. doi:10.1016/0370-2693(90)90275-B.

- ^ Wang, Z.Y. (2016). "Modern Theory for Electromagnetic Metamaterials". Plasmonics. 11 (2): 503–508. doi:10.1007/s11468-015-0071-7.

- ^ Veselago, V. G. (1968). "The electrodynamics of substances with simultaneously negative values of permittivity and permeability". Soviet Physics Uspekhi. 10 (4): 509–514. Bibcode:1968SvPhU..10..509V. doi:10.1070/PU1968v010n04ABEH003699.

- ^ Gimon, Eric G.; Hořava, Petr (2004). "Over-rotating black holes, Gödel holography and the hypertube". arXiv:hep-th/0405019.

{{cite arXiv}}:|class=ignored (help) - ^ Magueijo, João; Albrecht, Andreas (1999). "A time varying speed of light as a solution to cosmological puzzles". Physical Review D. 59 (4). arXiv:astro-ph/9811018. Bibcode:1999PhRvD..59d3516A. doi:10.1103/PhysRevD.59.043516.

- ^ "SI base units".

- ^ "constants".

References

- Falla, D. F.; Floyd, M. J. (2002). "Superluminal motion in astronomy". European Journal of Physics. 23: 69–81. Bibcode:2002EJPh...23...69F. doi:10.1088/0143-0807/23/1/310.

- Kaku, Michio (2008). "Faster than Light". Physics of the Impossible. Allen Lane. pp. 197–215. ISBN 978-0-7139-9992-1.

- Nimtz, Günter (2008). Zero Time Space. Wiley-VCH. ISBN 978-3-527-40735-4.

- Cramer, J. G. (2009). "Faster-than-Light Implications of Quantum Entanglement and Nonlocality". In Millis, M. G.; et al. (eds.). Frontiers of Propulsion Science. American Institute of Aeronautics and Astronautics. pp. 509–529. ISBN 1-56347-956-7.

External links

Scientific links

- Measurement of the neutrino velocity with the OPERA detector in the CNGS beam

- Encyclopedia of laser physics and technology on "superluminal transmission", with more details on phase and group velocity, and on causality

- July 22, 1997, The New York Times Company: Signal Travels Farther and Faster Than Light Far Apart, 2 Particles Respond Faster Than Light Archives

- Markus Pössel: Faster-than-light (FTL) speeds in tunneling experiments: an annotated bibliography

- Alcubierre, Miguel; The Warp Drive: Hyper-Fast Travel Within General Relativity, Classical and Quantum Gravity 11 (1994), L73–L77

- A systemized view of superluminal wave propagation

- Relativity and FTL Travel FAQ

- Usenet Physics FAQ: is FTL travel or communication Possible?

- Superluminal

- Relativity, FTL and causality

- Superluminal velocity fusing with Einstein special relativity

- Stimulated Generation of Superluminal Light Pulses via Four-Wave Mixing doi:10.1103/PhysRevLett.108.173902

Proposed FTL Methods links

- Conical and paraboloidal superluminal particle accelerators

- Relativity and FTL (=Superluminal motion) Travel Homepage