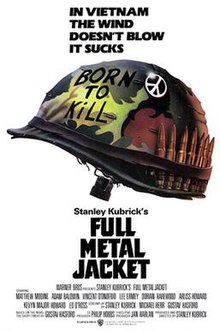

Full Metal Jacket

| Full Metal Jacket | |

|---|---|

Theatrical release poster | |

| Directed by | Stanley Kubrick |

| Screenplay by |

|

| Produced by | Stanley Kubrick |

| Starring | |

| Cinematography | Douglas Milsome |

| Edited by | Martin Hunter |

| Music by | Abigail Mead |

| Distributed by |

|

Release dates |

|

Running time | 116 minutes[2] |

| Countries |

|

| Language | English |

| Budget | $30 million[3] |

| Box office | $46.4 million (North America)[3] |

Full Metal Jacket is a 1987 war film directed and produced by Stanley Kubrick. The screenplay by Kubrick, Michael Herr and Gustav Hasford was based on Hasford's 1979 novel The Short-Timers. The film stars Matthew Modine, Adam Baldwin, Vincent D'Onofrio, R. Lee Ermey, Dorian Harewood, Arliss Howard, Kevyn Major Howard and Ed O'Ross. The story follows a platoon of U.S. Marines through their training and the experiences of two of the platoon's Marines in the Tet Offensive during the Vietnam War. The film's title refers to the full metal jacket bullet used by infantry riflemen. The film was released in the United States on June 26, 1987.

The film received critical acclaim, and an Academy Award nomination for Best Adapted Screenplay for Kubrick, Michael Herr and Gustav Hasford. In 2001, the American Film Institute placed Full Metal Jacket at No. 95 in their "AFI's 100 Years...100 Thrills" poll.

Plot

In 1967, during the Vietnam War, a group of new U.S. Marine Corps recruits arrives at Parris Island for basic training. After having their heads shaved, they meet their Senior Drill Instructor, Gunnery Sergeant Hartman. Hartman employs draconian tactics to turn the recruits into hardened Marines prepared for combat. Among the recruits are Privates "Joker", "Cowboy", and the overweight, bumbling Leonard Lawrence, who earns the nickname "Gomer Pyle" after attracting Hartman's wrath.

Unresponsive to Hartman's discipline, Pyle is eventually paired with Joker. Pyle improves with Joker's help, but his progress halts when Hartman discovers a contraband jelly doughnut in Pyle's foot locker. Believing that the recruits have failed to improve Pyle, Hartman adopts a collective punishment policy: every mistake Pyle makes will earn punishment for the rest of the platoon, with Pyle being spared. In retaliation, the platoon hazes Pyle with a blanket party, restraining him to his bunk and beating him with bars of soap wrapped in towels. After this incident, Pyle reinvents himself as a model Marine. This impresses Hartman, but worries Joker, who recognizes signs of mental breakdown in Pyle, such as talking to his M14 rifle.

Following their graduation the recruits receive their Military Occupational Specialty assignments; Joker is assigned to Basic Military Journalism. During the platoon's final night on Parris Island, Joker discovers Pyle in the bathroom loading his rifle with ammunition. Joker attempts to calm Pyle, who executes drill commands and recites the Rifleman's Creed. The noise awakens the platoon and Hartman. Hartman confronts Pyle and orders him to surrender the rifle. Pyle kills Hartman, and then commits suicide.

In January 1968, Joker, now a Sergeant, is a war correspondent in Vietnam for Stars and Stripes with Private First Class Rafterman, a combat photographer. Rafterman wants to go into combat, as Joker claims he has done. At the Marine base, Joker is mocked for his lack of the thousand-yard stare, indicating his lack of war experience. They are interrupted by the start of the Tet Offensive as the North Vietnamese Army attempts to overrun the base.

The following day, the journalism staff is briefed about enemy attacks throughout South Vietnam. Joker is sent to Phu Bai, accompanied by Rafterman. They meet the Lusthog Squad, where Cowboy is now a Sergeant. Joker accompanies the squad during the Battle of Huế, where platoon commander "Touchdown" is killed by the enemy. After the area is declared secure by the Marines, a team of American news journalists and reporters enter Huế and interview various Marines about their experiences in Vietnam and their opinions about the war.

During patrol, Crazy Earl, the squad leader, is killed by a booby trap, leaving Cowboy in command. The squad becomes lost and Cowboy orders Eightball to scout the area. A Viet Cong sniper wounds Eightball and the squad medic, Doc Jay, is wounded himself in an attempt to save him against orders. Cowboy learns that tank support is not available and orders the team to prepare for withdrawal. The squad's machine gunner, Animal Mother disobeys Cowboy and attempts to save his teammates. He discovers there is only one sniper, but Doc Jay and Eightball are killed when Doc attempts to indicate the sniper's location. While maneuvering towards the sniper, Cowboy is shot and killed.

Animal Mother assumes command of the squad and leads an attack on the sniper. Joker discovers the sniper, a teenage girl, and attempts to shoot her, but his rifle jams and alerts her to his presence. Rafterman shoots the sniper, mortally wounding her. As the squad converge, the sniper begs for death, prompting an argument about whether or not to kill her. Animal Mother decides to allow a mercy killing only if Joker performs it. After some hesitation, Joker shoots her. The Marines congratulate him on his kill as Joker stares into the distance, displaying the thousand-yard stare. The Marines march toward their camp, singing the Mickey Mouse March. Joker states that despite being "in a world of shit," he is glad to be alive and no longer afraid.

Cast

- Matthew Modine as Private/Corporal/Sergeant James T. "Joker" Davis. The narrator who joined the U.S. Marine Corps to see combat, and later becomes an independent-minded combat correspondent. Joker wears a peace sign medallion on his uniform as well as writing "Born to Kill" on his M1 Helmet, which he explains as an expression of Jungian philosophy concerning the duality of man.

- Vincent D'Onofrio as Private Leonard "Gomer Pyle" Lawrence. An overweight, clumsy, slow-witted recruit who becomes the focus of Hartman's attention for his incompetence and excess weight. D'Onofrio was required to gain weight for the role and added 70 pounds (32 kg; 5 st 0 lb) to his frame, for a total weight of 280 pounds (130 kg; 20 st 0 lb). This weight gain broke the record for the largest weight gained for a role, set by Robert De Niro for Raging Bull (1980). It took D'Onofrio nine months to shed the excess weight.[4][5]

- R. Lee Ermey as Gunnery Sergeant Hartman, a Parris Island drill instructor who trains his recruits to transform them into Marines. Ermey actually served as a U.S. Marine drill instructor during the Vietnam War. Based on this experience, he ad libbed much of his dialogue in the film.

- Arliss Howard as Private/Sergeant Robert "Cowboy" Evans. A Texan who attends boot camp with Joker and Pyle. He becomes a rifleman and later encounters Joker in Vietnam, where Cowboy takes command of a rifle squad.

- Adam Baldwin as Sergeant "Animal Mother", the nihilistic M60 machine gunner of the Lusthog Squad. His helmet bears the inscription: "I Am Become Death," a quotation from the Bhagavad Gita.

- Dorian Harewood as Corporal "Eightball". An African-American member of the Lusthog Squad, insensitive about his ethnicity (e.g. "Put a nigger behind the trigger"), and Animal Mother's closest friend.

- Kevyn Major Howard as Private First Class "Rafterman". Rafterman works as a combat photographer in the Stars and Stripes office with Joker.

- Ed O'Ross as Lieutenant Walter J. "Touchdown" Schinoski. The commander of the Lusthog Squad's platoon. His nickname comes from having "played a little football for Notre Dame."

- John Terry as Lieutenant Lockhart. The PAO officer in charge and Joker's assignment editor.

- Kieron Jecchinis as Sergeant "Crazy Earl". The squad leader, he is forced to assume platoon command when Schinoski is killed. As in the novel he carries a BB gun, which is visible just before he dies.

- John Stafford as Doc Jay: A U.S. Navy Hospital Corpsman attached to the Lusthog Squad.

- Tim Colceri as the door gunner of the helicopter transporting Joker and Rafterman to the Tet Offensive front. He was initially cast to play Hartman, which ultimately went to Ermey.[6] In flight, he shoots at civilians while enthusiastically repeating "Get some!", boasting "157 dead Gooks killed, and 50 water buffaloes too." When Joker asks if that includes women and children, he admits it stating, "Sometimes." Joker then asks, "How could you shoot women and children?" to which the door gunner replies, "Easy, you just don't lead 'em so much!" This scene is adapted from Michael Herr's 1977 book Dispatches.

- Peter Edmund as Private "Snowball" Brown, an African-American recruit, the butt of Hartman's racial jibes.

- Bruce Boa as a belligerent colonel, who demands to know why Joker wears a peace symbol on his body armor when he also has the words 'Born to Kill' written on his helmet.

Production

Development

Kubrick contacted Michael Herr, author of the critically acclaimed Vietnam War memoir Dispatches (1977), in the spring of 1980 to discuss working on a film about the Holocaust, but eventually discarded that in favor of a film about the Vietnam War.[7] They met in England and the director told him that he wanted to do a war film but he had yet to find a story to adapt.[8] Kubrick discovered Gustav Hasford's novel The Short-Timers while reading the Virginia Kirkus Review[9] and Herr received it in bound galleys and thought that it was a masterpiece.[8] In 1982, Kubrick read the novel twice and afterwards thought that it "was a unique, absolutely wonderful book" and decided, along with Herr,[7] that it would be the basis for his next film.[9] According to the filmmaker, he was drawn to the book's dialogue that was "almost poetic in its carved-out, stark quality."[9] In 1983, he began researching for this film, watching past footage and documentaries, reading Vietnamese newspapers on microfilm from the Library of Congress, and studied hundreds of photographs from the era.[10] Initially, Herr was not interested in revisiting his Vietnam War experiences and Kubrick spent three years persuading him in what the author describes as "a single phone call lasting three years, with interruptions."[7]

In 1985, Kubrick contacted Hasford to work on the screenplay with him and Herr,[8] often talking to Hasford on the phone three to four times a week for hours at a time. [11] Kubrick had already written a detailed treatment.[8] Kubrick and Herr got together at Kubrick's home every day, breaking down the treatment into scenes. From that, Herr wrote the first draft.[8] The filmmaker was worried that the title of the book would be misread by audiences as referring to people who only did half a day's work and changed it to Full Metal Jacket after discovering the phrase while going through a gun catalogue.[8] After the first draft was completed, Kubrick would phone in his orders and Hasford and Herr would mail in their submissions.[12] Kubrick would read and then edit them with the process starting over. Neither Hasford nor Herr knew how much they contributed to the screenplay and this led to a dispute over the final credits.[12] Hasford remembers, "We were like guys on an assembly line in the car factory. I was putting on one widget and Michael was putting on another widget and Stanley was the only one who knew that this was going to end up being a car."[12] Herr says that the director was not interested in making an anti-war film but that "he wanted to show what war is like."[7]

At some point, Kubrick wanted to meet Hasford in person but Herr advised against this, describing The Short-Timers author as a "scary man."[7] Kubrick insisted. They all met at Kubrick's house in England for dinner. It did not go well, and Hasford was subsequently shut out of the production.[7]

Adaptation of novel to film

Film scholar Greg Jenkins has done a detailed analysis of the transition of the story from book to film. The novel is in three parts, while the film largely discards Part III, and massively expands the book's relatively brief first part about the boot camp on Parris Island. This gives the film a duplex structure of telling two largely separate stories connected by the same characters, one which Jenkins believes is consistent with statements Kubrick made back in the 1960s of wanting to explode the usual conventions of narrative structure.[13]

Sergeant Hartman (renamed from the book's Gerheim) is given an expanded presence in the film. The film is more focused on Private Pyle's incompetence as a presence that weighs negatively on the rest of the platoon. In the film, unlike the novel, he is the only under-performing recruit. [14] The film omits "Hartman's" disclosure to other troops that he thinks Pyle might be mentally unstable, a "Section Eight." By contrast, Hartman congratulates Pyle that he is "born again hard". Jenkins believes that to have Hartman be in any way social with the troops would have upset the balance of the film, which depends on the spectacle of ordinary soldiers coming to grips with Hartman as a force of nature embodying a killer culture.[15]

Various episodes from the book have been both cut and conflated with others in the film. Sequences such as Cowboy's introduction of the "Lusthog Squad" have both been drastically shortened and supplemented by material from other sections of the book. Although the book's final third section was largely dropped, pieces of material in it have been inserted into other episodes of the film.[16] The climactic episode with the sniper is a conflation of two episodes in the book, one from part two, and another from part three. Jenkins sees the film's handling of this episode as both more dramatic but less gruesome than its counterpart in the novel.

The film often has a more tragic tone than the book, which often falls back on callous humor. Joker in the film remains a model of humane thinking, as evidenced by his moral struggle in the sniper episode and elsewhere. His struggle in the film is to overcome his own meekness, rather than to compete with other Marines. Hence, the film omits his eventual domination over Animal Mother.[17]

The film omits the death of the character Rafterman. Jenkins believed this allowed viewers to reflect on his personal growth in the film, and speculate on his further growth afterwards. Jenkins also believed it would not fit into the film's plot structure.[16]

Casting

Through Warner Bros., Kubrick advertised a national search in the United States and Canada. The director used videotape to audition actors. He received over 3,000 videotapes. His staff screened all of the tapes and eliminated the unacceptable ones. This left 800 tapes for Kubrick to personally review.[8]: 461

Former U.S. Marine Drill Instructor Ermey was originally hired as a technical adviser and asked Kubrick if he could audition for the role of Hartman. Kubrick, having seen his portrayal as Drill Instructor Staff sergeant Loyce in The Boys in Company C, told him that he was not vicious enough to play the character. In response, Ermey showcased his ability to play the character, as well as demonstrating just how a Drill Instructor breaks down the individuality of new recruits, by improvising insulting dialogue towards a group of Royal Marines who were being considered for the part of background Marines.[8]: 462 Upon viewing the videotape of these sessions, Kubrick gave Ermey the role, realizing that he "was a genius for this part",[10] and incorporated the 250-page transcript of Ermey's rants into the script.[8]: 462–463 Ermey's experience as a real-life Drill Instructor during the Vietnam era proved invaluable in this area. According to Kubrick's estimate, the former drill instructor wrote 50% of his own dialogue, especially the insults.[18]

While Ermey practiced his lines in a rehearsal room, a production assistant would throw tennis balls and oranges at him. Ermey had to catch the ball and throw it back as quickly as possible, while at the same time saying his lines as fast as he could. Any hesitation, slur, or missed line would necessitate starting over. 20 error-free runs were required. "[He] was my drill instructor," Ermey said of the production assistant.[8]: 463

The original plan envisaged Anthony Michael Hall starring as Private Joker, but after eight months of negotiations, a deal between Kubrick and Hall fell through.[19] Kubrick offered Bruce Willis a role, but Willis had to turn down the opportunity because of the impending start of filming on the first six episodes of Moonlighting.[20]

Vincent D'Onofrio heard of the auditions for the film from Matthew Modine. Using a rented video camera and dressed in army fatigues, he recorded his audition for the part of Private Pyle. Despite Kubrick calling Pyle "the hardest part to cast in the whole movie," D'onofrio received a quick response to his submission, informing him that the part was his.[8]: 465

Filming

Kubrick shot the film in England: in Cambridgeshire, on the Norfolk Broads, and at the former Millennium Mills and Beckton Gas Works, Newham (east London). A former RAF and then British Army base, Bassingbourn Barracks, doubled as the Parris Island Marine boot camp.[10] A British Army rifle range near Barton, outside Cambridge, was used in the scene where Private Pyle is congratulated on his shooting skills by Hartman. The disused Beckton Gas Works a few miles from central London portrayed the ruined city of Huế. Kubrick worked from still photographs of Huế taken in 1968 and found an area owned by British Gas that closely resembled it and was scheduled to be demolished.[18] To achieve this look, Kubrick had buildings blown up and the film's art director used a wrecking ball to knock specific holes in certain buildings over the course of two months.[18] Originally, Kubrick had a plastic replica jungle flown in from California but once he looked at it was reported to have said, "I don't like it. Get rid of it."[21] The open country is Cliffe marshes, also on the Thames, with 200 imported Spanish palm trees[9] and 100,000 plastic tropical plants from Hong Kong.[18]

Kubrick acquired four M41 tanks from a Belgian army colonel (a fan), and Westland Wessex helicopters painted Marine green to represent Marine Corps Sikorsky H-34 Choctaw helicopters. Although the Wessex was a licensed derivative of the Sikorsky H-34, the Wessex substituted two gas turbine engines for the H-34's radial (piston) engine. This resulted in a much longer and less rounded nose than that of the Vietnam era H-34. Kubrick also obtained a selection of rifles, M79 grenade launchers and M60 machine guns from a licensed weapons dealer.[10]

Modine described the shoot as difficult: the filming location for Vietnam, Beckton Gas Works, was a toxic and environmental nightmare for the entire film crew. Asbestos and hundreds of chemicals poisoned the earth and air. Modine documents details of shooting at Beckton in his book, Full Metal Jacket Diary. During the 'Boot Camp' sequence of the film, Modine and the other recruits had to endure the rigors of Marine Corp training, including having Ermey yelling at them for ten hours a day during the shooting of the Parris Island scenes. To ensure that the actors' reactions to Ermey were as authentic and genuine as possible, Ermey and the recruits would not rehearse together.[8]: 468 For film continuity, each recruit had to have his head shaved once a week.[22]

At one point during filming, Ermey had a car accident, broke all of his ribs on one side and was out for four-and-half months.[18] Cowboy's death scene shows a building in the background that resembles the famous alien monolith in Kubrick's 2001: A Space Odyssey. Kubrick described the resemblance as an "extraordinary accident."[18]

During filming, Hasford contemplated legal action over the writing credit. Originally the filmmakers intended Hasford to receive an "additional dialogue" credit, but he wanted full credit.[12] The writer took two friends and sneaked onto the set dressed as extras only to be mistaken by a crew member for Herr.[11]

Kubrick's daughter Vivian — who appears uncredited as a news-camera operator at the mass grave—shadowed the filming of Full Metal Jacket and shot eighteen hours of behind-the-scenes footage for a potential "making-of" documentary similar to her earlier film documentary on Kubrick's The Shining; however, in this case, her work did not come to fruition. Snippets of her work can be seen in the 2008 documentary Stanley Kubrick's Boxes.

Themes

Compared to Kubrick's other works, the themes of Full Metal Jacket have received little attention from critics and reviewers. Michael Pursell's essay "Full Metal Jacket: The Unravelling of Patriarchy" (1988) was an early, in-depth consideration of its two-part structure and its criticism of masculinity, arguing that the film shows "war and pornography as facets of the same system."[23] Most reviews have focused on military brainwashing themes in the boot camp training section of the film, while seeing the latter half of the film as more confusing and disjointed in content. Rita Kempley of The Washington Post wrote, "it's as if they borrowed bits of every war movie to make this eclectic finale."[24] Roger Ebert explained, "The movie disintegrates into a series of self-contained set pieces, none of them quite satisfying."[25] Julian Rice in his book Kubrick's Hope sees the second part of the film as continuing the psychic journey of Joker in trying to come to grips with human evil.[26]

Tony Lucia of the Reading Eagle, in his July 5, 1987 review of Full Metal Jacket looked at the themes of Kubrick's career, suggesting "the unifying element may be the ordinary man dwarfed by situations too vast and imposing to handle" specifically citing the "military mentality" from this film. He also explained that the theme further covered "a man testing himself against his own limitations" and that ultimately "'Full Metal Jacket' is the latest chapter in an ongoing movie which is not merely a comment on our time or a time past, but on something that reaches beyond."[27]

In a provocative essay on Full Metal Jacket, British critic Gilbert Adair wrote that "Kubrick's approach to language has always been reductive and uncompromisingly deterministic in nature. He appears to view it as the exclusive product of environmental conditioning, only very marginally influenced by concepts of subjectivity and interiority, by all the whims, shades and modulations of personal expression".[28] Michael Herr wrote of his work on the script for the film: "The substance was single-minded, the old and always serious problem of how you put into a film or a book the living, behaving presence of what Jung called The Shadow, the most accessible of archetypes, and the easiest to experience... War is the ultimate field of Shadow-activity, where all of its other activities lead you. As they expressed it in Vietnam, "Yea, though I walk through the Valley of the Shadow of Death, I will fear no Evil, for I am the Evil".[29]

Music

In addition to her work preparing a documentary, Vivian Kubrick, under the alias "Abigail Mead," wrote the score for the film. According to an interview which appeared in the January 1988 issue of Keyboard Magazine, the film was scored mostly with a Fairlight CMI synthesizer (the then-current Series III edition) and a Synclavier. For the period music, Kubrick went through Billboard's list of Top 100 Hits for each year from 1962–1968 and tried many songs but "sometimes the dynamic range of the music was too great, and we couldn't work in dialogue."[18]

- Johnnie Wright – "Hello Vietnam"

- The Dixie Cups – "Chapel of Love"

- Sam the Sham & The Pharaohs – "Wooly Bully"

- Chris Kenner – "I Like It Like That"

- Nancy Sinatra – "These Boots Are Made for Walkin'"

- The Trashmen – "Surfin' Bird"

- Goldman Band – "Marines' Hymn"

- The Rolling Stones – "Paint It Black" (end credits)

A single, "Full Metal Jacket (I Wanna Be Your Drill Instructor)," credited to Mead and Nigel Goulding, was released to promote the film. It incorporates Ermey's drill cadences from the film. The single reached number two in the UK pop charts.[30]

Release

Box office

Full Metal Jacket received a limited release on June 26, 1987 in 215 theaters.[3] Its opening weekend saw it accrue $2,217,307, an average of $10,313 per theater, ranking it the number 10 film for the June 26–28 weekend.[3] It took a further $2,002,890 for a total of $5,655,225 before entering wide release on July 10, 1987, at 881 theaters—an increase of 666.[3] The July 10–12 weekend saw the film gross $6,079,963, an average of $6,901 per theater, and rank as the number 2 grossing film. Over the next four weeks the film opened in a further 194 theaters to its widest release of 1,075 theaters before closing two weeks later with a total gross of $46,357,676, making it the number 23 highest grossing film of 1987.[3][31]

Home video

The film was released on Blu-ray on October 23, 2007 in the US and other countries.[32] On April 9, 2012, Warner Home Video announced that they would release the 25th anniversary edition on Blu-ray on August 7, 2012.[33]

Critical reception

Full Metal Jacket garnered critical acclaim following its release. Review aggregation website Rotten Tomatoes retrospectively collected reviews to give the film a score of 94% based on reviews from 70 critics, with an average rating of 8.4 out of 10.[34][35] Another aggregator Metacritic gave it a score of 78 out of 100, which indicates a "generally favorable" response, based on 18 reviews.[36] Reviewers generally reacted favorably to the cast, Ermey in particular,[37][38] and the film's first act in recruit training,[39][40] but several reviews were critical towards the latter part of the film set in Vietnam and what was considered a "muddled" moral message in the finale.[41][42] It ranks #95 on AFI's 100 Years... 100 Thrills.[43]

Richard Corliss of Time called the film a "technical knockout," praising "the dialogue's wild, desperate wit; the daring in choosing a desultory skirmish to make a point about war's pointlessness" and "the fine, large performances of almost every actor," believing, at the time, that Ermey and D'Onofrio would receive Oscar nominations. Corliss also appreciated "the Olympian elegance and precision of Kubrick's filmmaking."[37] Empire's Ian Nathan awarded the film 3 out of 5 stars, saying that it is "inconsistent" and describing it as "both powerful and frustratingly unengaged." Nathan felt that after leaving the opening act following the recruit training, the film becomes "bereft of purpose" but summarized his review by calling it a "hardy Kubrickian effort that warms on you with repeated viewings." Nathan also praised Ermey's "staggering performance."[40] Vincent Canby of The New York Times called it "harrowing, beautiful and characteristically eccentric." Canby echoed praise for Ermey, calling him "the film's stunning surprise...he's so good - so obsessed - that you might think he wrote his own lines". Canby also said that D'Onofrio's performance should be noted with "admiration," and called Modine "one of the best, most adaptable young film actors of his generation." Canby concluded that Full Metal Jacket was "a film of immense and very rare imagination."[44]

Jim Hall writing for Film4 in 2010 awarded the film 5 out of 5 stars and added to the praise for Ermey, saying his "performance as the foul-mouthed Hartman is justly celebrated and it's difficult to imagine the film working anything like as effectively without him." The review also preferred the opening training to the later Vietnam sequence, calling it "far more striking than the second and longer section." Film4 commented that the film ends abruptly but felt that "it demonstrates just how clear and precise the director's vision could be when he resisted a fatal tendency for indulgence." Film4 concluded that "Full Metal Jacket ranks with Dr. Strangelove as one of Kubrick's very best."[39] Jonathan Rosenbaum of the Chicago Reader called it "Elliptical, full of subtle inner rhymes...and profoundly moving, this is the most tightly crafted Kubrick film since Dr. Strangelove, as well as the most horrific."[45] Variety called the film an "intense, schematic, superbly made" drama "loaded with vivid, outrageously vulgar military vernacular that contributes heavily to the film's power," but felt that it never develops "a particularly strong narrative." The cast performances were all labeled "exceptional" with Modine being singled out as "embodying both what it takes to survive in the war and a certain omniscience."[38] Gilbert Adair, writing in a review for Full Metal Jacket, commented that "Kubrick's approach to language has always been of a reductive and uncompromisingly deterministic nature. He appears to view it as the exclusive product of environmental conditioning, only very marginally influenced by concepts of subjectivity and interiority, by all whims, shades and modulations of personal expression".[46]

Not all reviews were positive. Chicago Sun-Times critic Roger Ebert held a dissenting view, calling the film "strangely shapeless" and awarding it 2.5 stars out of 4. Ebert called it "one of the best-looking war movies ever made on sets and stage" but felt this was not enough to compete with the "awesome reality of Platoon, Apocalypse Now and The Deer Hunter." Ebert also criticized the film's second act set in Vietnam, saying the "movie disintegrates into a series of self-contained set pieces, none of them quite satisfying" and concluded that the film's message was "too little and too late," having been done by other Vietnam war films. However, Ebert also gave praise to Ermey and D'Onofrio, saying "these are the two best performances in the movie, which never recovers after they leave the scene."[42] This certain review angered Gene Siskel on their television show At The Movies, he criticized Ebert for liking Benji the Hunted (which came out the same week) more than Full Metal Jacket.[47] Their difference in opinion was parodied on the television show The Critic, where Siskel taunts Ebert with "coming from the guy who liked Benji the Hunted!"[48]Time Out London also disliked the film saying "Kubrick's direction is as steely cold and manipulative as the régime it depicts," and felt that the characters were underdeveloped, adding "we never really get to know, let alone care about, the hapless recruits on view."[41]

British television channel Channel 4 voted it number 5 on its list of the greatest war films ever made.[49] In 2008, Empire placed Full Metal Jacket number 457 on its list of the The 500 Greatest Movies of All Time.[50]

Accolades

Full Metal Jacket was nominated for eleven awards worldwide between 1987 and 1989 including an Academy Award for Best Adapted Screenplay,[51][52] two BAFTA Awards for Best Sound and Best Special Effects,[53] and a Golden Globe for Best Supporting Actor for Ermey.[54] Ultimately it won five awards, three from organisations outside of the United States: Italy, Japan, and the United Kingdom. The film won Best Foreign Language Film from the Japanese Academy, Best Producer from the David di Donatello Awards,[55] Director of the Year from the London Critics Circle Film Awards, and Best Director and Best Supporting Actor from the Boston Society of Film Critics Awards, for Kubrick and Ermey respectively.[56] Of the five awards won, four were awarded to Kubrick.

| Year | Award | Category | Recipient | Result | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1987 | BAFTA Awards | Best Sound | Nigel Galt, Edward Tise and Andy Nelson | Nominated | [53] |

| Best Special Effects | John Evans | Nominated | [53] | ||

| 1988 | 60th Academy Awards | Best Adapted Screenplay | Stanley Kubrick, Michael Herr and Gustav Hasford | Nominated | [51][52] |

| Boston Society of Film Critics Awards | Best Director | Stanley Kubrick | Won | [56] | |

| Best Supporting Actor | R. Lee Ermey | Won | |||

| David di Donatello Awards | Best Producer - Foreign film | Stanley Kubrick | Won | [55] | |

| Golden Globes | Best Performance by an Actor in a Supporting Role in a Motion Picture | R. Lee Ermey | Nominated | [54] | |

| London Critics Circle Film Awards | Director of the Year | Stanley Kubrick | Won | ||

| Writers Guild of America | Best Adapted Screenplay | Stanley Kubrick, Michael Herr, Gustav Hasford | Nominated | ||

| 1989 | Kinema Junpo Awards | Best Foreign Language Film Director | Stanley Kubrick | Won | |

| Awards of the Japanese Academy | Best Foreign Language Film | Stanley Kubrick | Nominated |

References

Notes

- ^ "Full Metal Jacket (1987)". British Film Institute. Retrieved October 20, 2011.

- ^ "FULL METAL JACKET". British Board of Film Classification. Retrieved January 14, 2015.

- ^ a b c d e f "Full Metal Jacket (1987)". Box Office Mojo. Retrieved August 1, 2011.

- ^ a b Bennetts, Leslie (10 July 1987). "The Trauma of Being a Kubrick Marine". The New York Times. Retrieved 30 April 2009.

- ^ Harrington, Amy (19 October 2009). "Stars Who Lose and Gain Weight for Movie Roles". Fox News Channel. News Corporation. Retrieved 23 October 2011.

- ^ Full Metal Jacket Blu-Ray DVD - Additional Material

- ^ a b c d e f CVulliamy, Ed (July 16, 2000). "It Ain't Over Till It's Over". The Observer. Retrieved 11 October 2007.

{{cite news}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help) - ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l LoBrutto, Vincent (1997). "Stanley Kubrick". Donald I. Fine Books.

{{cite news}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help) - ^ a b c d Clines, Francis X (June 21, 1987). "Stanley Kubrick's Vietnam". The New York Times. Retrieved 11 October 2007.

{{cite news}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help) - ^ a b c d Rose, Lloyd (28 June 1987). "Stanley Kubrick, At a Distance". The Washington Post. Retrieved 11 October 2007.

{{cite news}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help) - ^ a b Lewis, Grover (28 June 1987). "The Several Battles of Gustav Hasford". Los Angeles Times Magazine. Retrieved 11 October 2007.

{{cite news}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help) - ^ a b c d Carlton, Bob. "Alabama Native wrote the book on Vietnam Film". The Birmingham News. Retrieved 11 October 2007.

{{cite news}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help) - ^ Jenkins 1997, p. 128.

- ^ Jenkins 1997, p. 123.

- ^ Jenkins 1997, p. 124.

- ^ a b Jenkins 1997, p. 146.

- ^ Jenkins 1997, p. 147.

- ^ a b c d e f g Cahill, Tim (1987). "The Rolling Stone Interview". Rolling Stone. Retrieved 11 October 2007.

{{cite news}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help) - ^ Epstein, Dan. "Anthony Michael Hall from The Dead Zone – Interview". Underground Online. Retrieved 12 August 2009.

- ^ "Bruce Willis: Playboy Interview". Playboy. Playboy.com. Retrieved 28 July 2010.

- ^ Watson, Ian (2000). "Plumbing Stanley Kubrick". Playboy. Retrieved 11 October 2007.

{{cite news}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help) - ^ Linfield, Susan (October 1987). "The Gospel According to Matthew". American Film. Retrieved 11 October 2007.

{{cite news}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help) - ^ Pursell, Michael (1988). "Full Metal Jacket: The Unravelling of Patriarchy". Literature/Film Quarterly. 16 (4): 324.

- ^ Kempley, Rita. Review, The Washington Post.

- ^ Ebert, Roger. Review, Chicago Sun-Times, accessed 22 July 2010.

- ^ Rice, Julian (2008). Kubrick's Hope: Discovering Optimism from 2001 to Eyes Wide Shut. Scarecrow Press.

- ^ Lucia, Tony (July 5, 1987). "'Full Metal Jacket' takes deadly aim at the war makers" (Review). Reading Eagle. Reading, Pennsylvania. Retrieved March 23, 2014.

- ^ Baxter 1997, p. 10.

- ^ Baxter 1997, p. 11.

- ^ ChartStats

- ^ "Full Metal Jacket 1987". Box Office Mojo. Amazon.com. Retrieved 25 October 2011.

- ^ "Full Metal Jacket DVD Blu-ray". Retrieved 2012-05-06.

- ^ Ronald Epstein (2012-04-09). "WHV Press Release: Full Metal Jacket 25th Anniversary Blu-ray Book". Home Theater Forum. Retrieved 2012-05-06.

- ^ "Full Metal Jacket (1987)". Rotten Tomatoes. Time Warner. 20 October 2011. Retrieved 20 October 2011.

- ^ "The Undeclared War Over Full Metal Jacket". The Daily Beast. RTST, INC. Retrieved 28 July 2010.

- ^ "Full Metal Jacket". Metacritic. CBS Interactive. October 20, 2011. Retrieved 20 October 2011.

- ^ a b Corliss, Richard (29 June 1987). "Cinema: Welcome To Viet Nam, the Movie: II Full Metal Jacket". Time. Time Inc. Retrieved 20 October 2011.

- ^ a b "Full Metal Jacket". Variety. Reed Business Information. 31 December 1986. Archived from the original on 7 July 2011. Retrieved 7 July 2011.

{{cite news}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ a b Jim Hall (2010-01-05). "Fast & Furious 5". Film4. Channel Four Television Corporation. Retrieved 20 October 2011.

- ^ a b Nathan, Ian. "Full Metal Jacket". Empire. Bauer Media Group. Retrieved 20 October 2011.

- ^ a b "Full Metal Jacket (1987)". Time Out London. Time Out. Retrieved 21 October 2011.

- ^ a b Ebert, Roger. "Full Metal Jacket". rogerebert.com. rogerebert.com. Retrieved 28 July 2010.

- ^ "AFI list of America's most heart-pounding movies" (PDF). American Film Institute. Retrieved 21 February 2014.

- ^ Canby, Vincent (26 June 1987). "Kubrick's 'Full Metal Jacket,' on Vietnam". The New York Times. The New York Times Company. Retrieved 20 October 2011.

- ^ – Full Metal Jacket reviews at Metacritic.com

- ^ Duncan 2003, pp. 12–3.

- ^ http://www.thedailybeast.com/blogs-and-stories/2010-03-26/seven-classic-at-the-movies-moments/full/

- ^ The Critic TV Show Quotes, Retrojunk, Accessed January 4, 2011.

- ^ "Channel 4's 100 Greatest War Movies of All Time". Retrieved 13 August 2011.

- ^ "The 500 Greatest Movies of All Time". http://www.empireonline.com. Bauer Consumer Media. Retrieved 28 July 2010.

{{cite web}}: External link in|work= - ^ a b "The 60th Academy Awards (1988) Nominees and Winners". oscars.org. Retrieved 16 October 2011.

- ^ a b "Full Metal Jacket (1987)". nytimes.com. Retrieved 22 July 2010.

- ^ a b c "Film Nominations 1987". bafta.org. Retrieved 16 October 2011.

- ^ a b "Awards Search". goldenglobes.org. Retrieved 16 October 2011.

- ^ a b "David di Donatello Awards". daviddidonatello.it. Retrieved 16 October 2011.

- ^ a b "BSFC Past Award Winners". BSFC. Retrieved 13 July 2014.

- Bibliography

- Baxter, John (1997). Stanley Kubrick: A Biography. HarperCollins. ISBN 978-0-00-638445-8.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Duncan, Paul (2003). Stanley Kubrick: The Complete Films. Taschen GmbH. ISBN 978-3836527750.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Jenkins, Greg (1997). Stanley Kubrick and the Art of Adaptation: Three Novels, Three Films. McFarland. ISBN 978-0-7864-3097-0.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help)

External links

- 1987 films

- 1980s war films

- American war films

- British war drama films

- Anti-war films about the Vietnam War

- English-language films

- Films based on novels

- Films directed by Stanley Kubrick

- Films set in the 1960s

- Films set in South Carolina

- Films set in Vietnam

- Films shot in the United Kingdom

- Pinewood Studios films

- Screenplays by Stanley Kubrick

- United States Marine Corps in popular culture

- Vietnam War films

- Warner Bros. films