George R. R. Martin

George R. R. Martin | |

|---|---|

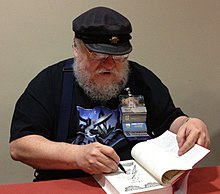

Martin at Archipelacon in Mariehamn, June 2015 | |

| Born | George Raymond Martin September 20, 1948 Bayonne, New Jersey, United States |

| Occupation |

|

| Nationality | American |

| Education | Northwestern University (B.S. Journalism, 1970; M.S. 1971) |

| Genre | |

| Notable works | A Song of Ice and Fire |

| Spouse | Gale Burnick

(m. 1975; div. 1979)Parris McBride (m. 2011) |

| Signature | |

| |

| Website | |

| www | |

George Raymond Richard Martin[3] (born George Raymond Martin; September 20, 1948), often referred to as GRRM,[4] is an American novelist and short story writer in the fantasy, horror, and science fiction genres, a screenwriter, and television producer. He is best known for his international bestselling series of epic fantasy novels, A Song of Ice and Fire, which was later adapted into the HBO dramatic series Game of Thrones.

Martin serves as the series' co-executive producer, and also scripted four episodes of the series. In 2005, Lev Grossman of Time called Martin "the American Tolkien",[5] and the magazine later named him one of the "2011 Time 100," a list of the "most influential people in the world."[6][7]

Early life

George Raymond Martin (he later adopted the confirmation name Richard, at thirteen years old)[8] was born on September 20, 1948,[9] in Bayonne, New Jersey,[10] the son of longshoreman Raymond Collins Martin and his wife Margaret Brady Martin. He has two younger sisters, Darleen and Janet. Martin's father was of half Italian descent, while his mother was of half Irish ancestry;[11] he also has German, English, and French roots.

The family first lived in a house on Broadway, belonging to Martin's great-grandmother. In 1953, they moved to a federal housing project near the Bayonne docks. During Martin's childhood, his world consisted predominantly of "First Street to Fifth Street", between his grade school and his home; this limited world made him want to travel and experience other places, but the only way of doing so was through his imagination, so he became a voracious reader.

When Martin's family moved to a larger apartment after his sister was born, he also had a view of the waters of the Kill van Kull, where freighters and oil tankers flying flags from distant countries were entering and leaving Port Newark. He had an encyclopedia with a list of flags, and when using it to figure out where the ships came from, he would find himself dreaming of traveling to these remote locations. After the sun went down, the lights from Staten Island would shine across the water, which in his imagination was Shangri-La and "Shanghai and Paris, Timbuctoo and Kalamazoo, Marsport and Trantor, and all the other places that I'd never been and could never hope to go".[12][13]

The young Martin began writing and selling monster stories for pennies to other neighborhood children, dramatic readings included. He also wrote stories about a mythical kingdom populated by his pet turtles; the turtles died frequently in their toy castle, so he finally decided they were killing each other off in "sinister plots".[14]

Martin attended Mary Jane Donohoe School and then later Marist High School. While there he became an avid comic-book fan, developing a strong interest in the innovative superheroes being published by Marvel Comics.[15] A letter Martin wrote to the editor of Fantastic Four was printed in issue No. 20 (Nov 1963); it was the first of many sent, e.g., FF #32, #34, and others from his family's home at 35 E. First Street, Bayonne, NJ. Fans who read his letters then wrote him letters in turn, and through such contacts, Martin joined the fledgling comics fandom of the era, writing fiction for various fanzines;[16] he was the first to register for an early comic book convention held in New York in 1964.[17] In 1965, Martin won comic fandom's Alley Award for his prose superhero story "Powerman vs. The Blue Barrier",[citation needed] the first of many awards he would go on to win for his fiction.

In 1970, Martin earned a B.S. in Journalism from Northwestern University, Evanston, Illinois, graduating summa cum laude; he went on to complete his M.S. in Journalism in 1971, also from Northwestern. Eligible for the draft during the Vietnam War, to which he objected, Martin applied for and obtained conscientious-objector status;[18] he instead did alternative service work for two years (1972–1974) as a VISTA volunteer, attached to the Cook County Legal Assistance Foundation. An expert chess player, he also directed chess tournaments for the Continental Chess Association from 1973 to 1976.[citation needed]

Teaching

In the mid-1970s, Martin met English professor George Guthridge from Dubuque, Iowa, at a science fiction convention in Milwaukee. Martin persuaded Guthridge (who confesses that at that time he despised science fiction and fantasy) not only to give speculative fiction a second look, but to write in the field himself. (Guthridge has since been a finalist for the Hugo Award and twice for the Nebula Award for science fiction and fantasy. In 1998, he won a Bram Stoker Award for best horror novel.)[citation needed]

In turn, Guthridge helped Martin find a job at Clarke University (then Clarke College). Martin "wasn't making enough money to stay alive", from writing and the chess tournaments, says Guthridge.[19] From 1976 to 1978, Martin was an English and journalism instructor at Clarke, and he became Writer In Residence at the college from 1978 to 1979.[citation needed]

While he enjoyed teaching, the sudden death of friend and fellow author Tom Reamy in late 1977 made Martin reevaluate his own life, and he eventually decided to try to become a full-time writer. He resigned from his job, and being tired of the hard winters in Dubuque, he moved to Santa Fe in 1979.[20]

Writing career

Martin began selling science fiction short stories professionally in 1970, at age 21. His first sale was "The Hero", sold to Galaxy magazine and published in its February 1971 issue; other sales soon followed. His first story to be nominated for the Hugo Award[21] and Nebula Awards was "With Morning Comes Mistfall", published in 1973 in Analog magazine. A member of the Science Fiction and Fantasy Writers of America (SFWA), Martin became the organization's Southwest Regional Director from 1977 to 1979; he served as its vice-president from 1996 to 1998.[citation needed]

In 1976, for Kansas City's MidAmeriCon, the 34th World Science Fiction Convention (Worldcon), Martin and his friend and fellow writer-editor Gardner Dozois conceived of and organized the first Hugo Losers' Party for the benefit of all past and present Hugo-losing writers, their friends and families, the evening following the convention's Hugo Awards ceremony. Martin was nominated for two Hugos that year but lost both awards, for the novelette "...and Seven Times Never Kill Man" and the novella The Storms of Windhaven, co-written with Lisa Tuttle.[22] The Hugo Losers' Party became an annual Worldcon event thereafter, and its formal title eventually changed to something a bit more politically correct as both its size and prestige grew.

Although Martin often writes fantasy or horror, a number of his earlier works are science fiction tales occurring in a loosely defined future history, known informally as "The Thousand Worlds" or "The Manrealm". He has also written at least one piece of political-military fiction, "Night of the Vampyres", collected in Harry Turtledove's anthology The Best Military Science Fiction of the 20th Century (2001).[23]

The unexpected commercial failure of Martin's fourth book, The Armageddon Rag (1983), "essentially destroyed my career as a novelist at the time", he recalled. However, that failure led him to seek a career in television [14] after a Hollywood option on that novel led to his being hired, first as a staff writer and then as an Executive Story Consultant, for the revival of the Twilight Zone. After the CBS series was cancelled, Martin migrated over to the already-underway satirical science fiction series Max Headroom. He worked on scripts and created the show's "Ped Xing" character (the president of the Zic Zak corporation, Network 23's primary sponsor). Before his scripts could go into production, however, the ABC show was cancelled in the middle of its second season. Martin was then hired as a writer-producer on the new dramatic fantasy series Beauty and the Beast; in 1989 he became the show's co-supervising producer and wrote 14 of its episodes.[24]

During this same period, Martin continued working in print media as a book-series editor, this time overseeing the development of the multi-author Wild Cards book series, which takes place in a shared universe in which a small slice of post–World War II humanity gains superpowers after the release of an alien-engineered virus; new titles are still being published in the ongoing series from Tor Books. In Second Person Martin "gives a personal account of the close-knit role-playing game (RPG) culture that gave rise to his Wild Cards shared-world anthologies".[25] An important element in the creation of the multiple author series was a campaign of Chaosium's role-playing game Superworld (1983), that Martin ran in Albuquerque.[26] Martin's own contributions to Wild Cards have included Thomas Tudbury, "The Great and Powerful Turtle", a powerful psychokinetic whose flying "shell" consisted of an armored VW Beetle. As of June 2011, 21 Wild Cards volumes had been published in the series; earlier that same year, Martin signed the contract for the 22nd volume, Low Ball (2014), published by Tor Books. In early 2012, Martin signed another Tor contract for the 23rd Wild Cards volume, High Stakes.

While he was making a satisfactory living in Hollywood, he did not feel fulfilled given that so few of the projects he worked on ever went into production; "No amount of money can really take the place of... you want your stuff to be read. You want an audience and four guys in an executive office suite at ABC or Columbia is not adequate."[27]

Martin's novella, Nightflyers (1980), was adapted into an eponymous 1987 feature film; he was unhappy about having to cut plot elements for the screenplay's scenario in order to accommodate the film's small budget.[28]

A Song of Ice and Fire

In 1991, Martin briefly returned to writing novels and began what would eventually turn into his epic fantasy series: A Song of Ice and Fire, which was inspired by the Wars of the Roses and Ivanhoe. It is currently intended to comprise seven volumes. The first, A Game of Thrones, was published in 1996. In November 2005, A Feast for Crows, the fourth novel in this series, became The New York Times No. 1 Bestseller and also achieved No. 1 ranking on The Wall Street Journal bestseller list. In addition, in September 2006, A Feast for Crows was nominated for both a Quill Award and the British Fantasy Award.[29] The fifth book, A Dance with Dragons, was published July 12, 2011, and quickly became an international bestseller, including achieving a No. 1 spot on the New York Times Bestseller List and many others; it remained on the New York Times list for 88 weeks. The series has received praise from authors, readers, and critics alike. In 2012, A Dance With Dragons made the final ballot for science fiction and fantasy's Hugo Award, World Fantasy Award, Locus Poll Award, and the British Fantasy Award; the novel went on to win the Locus Poll Award for Best Fantasy Novel. Two more novels are planned and still being written in the Ice and Fire series: The Winds of Winter and A Dream of Spring.

HBO adaptation

HBO Productions purchased the television rights for the entire A Song of Ice and Fire series in 2007 and began airing the fantasy series on their U. S. premium cable channel April 17, 2011. Titled Game of Thrones, it ran weekly for ten episodes, each approximately an hour long.[30] Although busy completing A Dance With Dragons and other projects, George R. R. Martin was heavily involved in the production of the television series adaptation of his books. Martin's involvement included the selection of a production team and participation in scriptwriting; the opening credits list him as a co-executive producer of the series. The series was renewed shortly after the first episode aired.

The first season was nominated for 13 Emmy Awards, ultimately winning two:

- one for its opening title credits, and

- one for Peter Dinklage as Best Supporting Actor.

The first season was also nominated for a 2012 Hugo Award, fantasy and science fiction's oldest award, presented by the World Science Fiction Society each year at the annual Worldcon; the show went on to win the 2012 Hugo for Best Dramatic Presentation, Long Form, at Chicon 7, the 70th World Science Fiction Convention, in Chicago, IL; Martin took home one of the three Hugo Award trophies awarded in that collaborative category, the other two going to Game of Thrones showrunners David Benioff and D.B. Weiss.

The second season, based on the second Ice and Fire novel A Clash of Kings, began airing on HBO in the U.S. April 1, 2012; the second season was nominated for 12 Emmy Awards, including another Supporting Actor nomination for Dinklage. It went on to win six of those Emmys in the Technical Arts categories, which were awarded the week before the regular televised 2012 awards show. The second season episode "Blackwater", written by George R.R. Martin, was nominated the following year for the 2013 Hugo Award in the Best Dramatic Presentation, Short Form category; that episode went on to win the Hugo Award at LoneStarCon 3, the 71st World Science Fiction Convention, in San Antonio, Texas. In addition to Martin, showrunners Benioff and Weiss (who contributed several scenes to the final screenplay) and episode director Neil Marshal (who expanded the scope of the episode on set) received Hugo statuettes.

Themes

Martin's work has been described by the Los Angeles Times as having "complex story lines, fascinating characters, great dialogue, perfect pacing".[31] While the New York Times sees it as "fantasy for grown ups",[32] others feel it is dark and cynical.[33] His first novel, Dying of the Light, set the tone for some of his future work; it unfolds on a mostly abandoned planet that is slowly becoming uninhabitable as it moves away from its sun. This story has a strong sense of melancholy. His characters are often unhappy or, at least, unsatisfied, in many cases holding on to idealisms in spite of an otherwise chaotic and ruthless world, in many cases troubled by their own self-seeking or violent actions, even as they undertake them. Many have elements of tragic heroes or antiheroes in them; reviewer T. M. Wagner writes, "Let it never be said Martin doesn't share Shakespeare's fondness for the senselessly tragic."[34]

The overall gloominess of A Song of Ice and Fire can be an obstacle for some readers; the Inchoatus Group writes, "If this absence of joy is going to trouble you, or you're looking for something more affirming, then you should probably seek elsewhere."[35] For many fans, however, it is precisely this level of "realness" and "completeness", including many characters' imperfections, moral and ethical ambiguity, and consequential plot twists (often sudden), that is endearing about Martin's work and keeps the series' story arcs compelling enough to keep following despite its sheer brutality and intricately messy/interwoven plotlines; as TM Wagner points out, "There's great tragedy here, but there's also excitement, humor, heroism even in weaklings, nobility even in villains, and, now and then, a taste of justice after all. It's a rare gift when a writer can invest his story with that much humanity."[34]

Martin's characters are multifaceted, each with intricate pasts, aspirations, and ambitions. Publishers Weekly writes of his ongoing epic fantasy A Song of Ice and Fire, "The complexity of characters such as Daenerys, Arya and the Kingslayer will keep readers turning even the vast number of pages contained in this volume, for the author, like Tolkien or Jordan, makes us care about their fates."[36] Misfortune, injury, and death (including false death and reanimation) often befall major or minor characters, no matter how attached the reader has become. Martin has described his penchant for killing off important characters as being necessary for the story's depth: "when my characters are in danger, I want you to be afraid to turn the page, (so) you need to show right from the beginning that you're playing for keeps".[37]

In distinguishing his work from others, Martin makes a point of emphasizing realism and plausible social dynamics above an over-reliance on magic and a simplistic "good versus evil" dichotomy, which contemporary fantasy writing is often criticized for. Notably, Martin's work makes a sharp departure from the prevalent "heroic knights and chivalry" schema that has become a mainstay in fantasy as derived from the Lord of the Rings series of J.R.R. Tolkien. He specifically critiques the oversimplification of Tolkien's themes and devices by imitators in ways that he has humorously described as "Disneyland Middle Ages"[38] that gloss over or even ignore major differences between medieval and modern societies, particularly social structures, ways of living, and political arrangements. Martin has been described as "the American Tolkien" by literary critics.[39] While Martin finds inspiration in Tolkien's legacy,[40] he aims to go beyond what he sees as Tolkien's "medieval philosophy" of "if the king was a good man, the land would prosper" to delve into the complexities, ambiguities, and vagaries of real-life power: "We look at real history and it's not that simple ... Just having good intentions doesn't make you a wise king."[41]

In fact, the author makes a point of grounding his work on a foundation of historical fiction, which he channels to evoke important social and political elements of primarily the European medieval era that differ markedly from elements of modern times, including the multigenerational, rigid, and often brutally consequential nature of the hierarchical class system of feudal societies[42] that is in many cases overlooked in fantasy writing. Even as A Song of Ice and Fire is a fantasy series that employs magic and the surreal as central to the genre, Martin is keen to ensure that magic is merely one element of many that moves his work forward,[43] not a generic deus ex machina that is itself the focus of his stories, something he has been very conscious about since reading Tolkien; "If you look at The Lord of the Rings, what strikes you, it certainly struck me, is that although the world is infused with this great sense of magic, there is very little onstage magic. So you have a sense of magic, but it's kept under very tight control, and I really took that to heart when I was starting my own series."[44] Martin's ultimate aim is an exploration of the internal conflicts that define the human condition, which, in deriving inspiration from William Faulkner,[45] he ultimately describes as the only reason to read any literature, regardless of genre.[46]

This nuanced, multi-layered, all-encompassing nature of Martin's work has consistently received accolades – his work has "captured the imaginations of millions for the same reason the archetypal dramas of Homer, Sophocles or Shakespeare have lasted for millennia. They show us the conflict between self-sacrifice and self-interest, between the human spirit and the human ego, between good and evil. And when we look up from the page we recognise those same conflicts in the world around us and in ourselves."[47][48]

Relationship with fans

Blog

Martin actively contributes to his blog, Not a Blog. He still does all his writing on an old DOS machine running Wordstar 4.0.[49]

Conventions

Martin is known for his regular attendance through the decades at science fiction conventions and comics conventions, and his accessibility to fans. In the early 1980s, critic and writer Thomas Disch identified Martin as a member of the "Labor Day Group", writers who regularly congregated at the annual Worldcon,[50] usually held on or around the Labor Day weekend. Since the early 1970s he has also attended regional science fiction conventions, and since 1986 Martin has participated annually in Albuquerque's smaller regional convention Bubonicon, near his New Mexico home.[51] He was invited to be Guest of Honor at the 61st World Science Fiction Convention in Toronto, held in 2003.[52][53]

Fan club

Martin's official fan club is the "Brotherhood Without Banners", who have a regular posting board at the Forum of the website westeros.org, which is focused on his Song of Ice and Fire fantasy series. At the annual World Science Fiction Convention every year, the BWB hosts a large, on-going hospitality suite that is open to all members of the Worldcon;[54] their suite frequently wins by popular vote the convention's best party award.[citation needed]

Fan criticism and response

Martin has been criticized by some of his readers for the long periods between books in the Ice and Fire series, notably the six-year gap between the fourth volume, A Feast for Crows (2005), and the fifth volume, A Dance with Dragons (2011).[55][56] The previous year, in 2010, Martin had responded to fan criticisms by saying he was unwilling to write only his Ice and Fire series, noting that working on other prose and compiling and editing different book projects has always been part of his working process.[57] Writer Neil Gaiman famously wrote on his blog in 2009 to a critic of Martin's pace, "George R. R. Martin is not your bitch." Gaiman later went on to state that writers aren't machines and that they have every right to work on other projects if they want to.[58]

Fan fiction

Martin is opposed to fan fiction, which he views as copyright infringement and a bad exercise for aspiring writers in terms of developing skills in world-building and character development.[59][60]

Personal life

In the early 1970s, Martin was in a relationship with fellow science-fiction/fantasy author Lisa Tuttle,[61] with whom he co-wrote Windhaven.

While attending an East Coast science fiction convention he met his first wife, Gale Burnick; they were married in 1975, but the marriage ended in divorce, without issue, in 1979. On February 15, 2011, Martin married his longtime partner Parris McBride during a small ceremony at their Santa Fe home. On August 19, 2011, they held a larger wedding ceremony and reception at Renovation, the 69th World Science Fiction Convention, in Reno, Nevada.[62]

He and his wife Parris are supporters of the Wild Spirit Wolf Sanctuary in New Mexico.[63] In early 2013 he purchased Santa Fe's Jean Cocteau Cinema and Coffee House, which had been closed since 2006. He had the property completely restored, including both its original 35 mm capability to which was added digital projection and sound; the Cocteau officially reopened for business on August 9, 2013.[64] Martin has also supported Meow Wolf, an arts collective in Santa Fe, having pledged $2.7 million towards a new art-space in January 2015.[65][66]

In response to a question on his religious views, Martin replied: "I suppose I'm a lapsed Catholic. You would consider me an atheist or agnostic. I find religion and spirituality fascinating. I would like to believe this isn't the end and there's something more, but I can't convince the rational part of me that makes any sense whatsoever."[67]

Martin is a fan of the New York Jets[68] and the New York Mets.[69]

Martin made a guest appearance as himself in an episode, "El Skeletorito", of an Adult Swim show, Robot Chicken.[citation needed] He also appeared in SyFy's Z Nation as a zombie version of himself in season two's "The Collector," where he is still signing copies of his new novel.[citation needed]

Philanthropy

In 2014, Martin launched a high-profile campaign on Prizeo to raise funds for two charities: Wild Spirit Wolf Sanctuary and the Food Depot of Santa Fe. As part of the campaign, Martin offered one donor the chance to accompany him on a trip to the wolf sanctuary, including a helicopter ride and dinner. Martin also offered those donating $20,000 or more the opportunity to have a character named after them in an upcoming A Song Of Ice And Fire novel and "killed off". The campaign garnered significant media attention and raised a total of $502,549.[70][71]

Politics

Growing up, Martin avoided the draft to the Vietnam War by being a conscientious objector and did two years of alternative service. He generally opposed the war and thought it was a "terrible mistake for America." He also opposes the idea of the glory of war and tries to realistically describe war in his books.[72]

In 2014, Martin endorsed Senator Tom Udall.[73]

In the midst of pressure to pull the 2014 feature film The Interview from theatres, the Jean Cocteau Theatre in Santa Fe, New Mexico, which has been owned by Martin since 2013, decided to show the film. "As a movie theater, we are not just involved in the entertainment business. We are involved in the First Amendment business, protecting our freedoms," theatre manager Jon Bowman told the Santa Fe New Mexican.[74]

On 20 November 2015, writing on his LiveJournal, Martin advocated for allowing Syrian refugees into the United States.[75]

Awards

- 1975 Hugo Award for Best Novella for "A Song for Lya"

- 1980 Hugo Award for Best Novelette for "Sandkings"

- 1980 Nebula Award for Best Novelette for "Sandkings" (This is Martin's only story to win both a Hugo and a Nebula.)

- 1980 Hugo Award for Best Short Story for "The Way of Cross and Dragon"

- 1986 Nebula Award for Best Novelette for "Portraits of His Children"

- 1988 Bram Stoker Award for Long Fiction for "The Pear-Shaped Man"

- 1989 World Fantasy Award for Best Novella for "The Skin Trade"

- 1997 Hugo Award for Best Novella for "Blood of the Dragon"

- 2003 Premio Ignotus for Best Foreign Novel for A Game of Thrones

- 2004 Premio Ignotus for Best Foreign Novel for A Clash of Kings

- 2003 Locus Award for Best Fantasy Novel for A Storm of Swords

- 2006 Premio Ignotus for Best Foreign Novel for A Storm of Swords

- 2011 Locus Award for Best Original Anthology for Warriors (co-edited with Gardner Dozois)

- Declared by Time "One of the Most Influential People of 2011"[6]

- 2012 Locus Award for Best Fantasy Novel for A Dance with Dragons

- 2012 Hugo Award for Best Dramatic Presentation, Long Form for Game of Thrones Season 1 (Co-Executive Producer of the HBO series)

- 2012 World Fantasy Award for Life Achievement

- 2013 Hugo Award for Best Dramatic Presentation, Short Form for Game of Thrones, Season 2, Episode 9, "Blackwater" (Screenwriter)

- 2014 Locus Award for Best Original Anthology for Old Mars (co-edited with Gardner Dozois)[76]

- 2015 Emmy Award for Best Drama Series- Game of Thrones (co-executive producer)

- 2015 Northwestern University Medill Hall of Achievement Award[77]

Nominations

- 1997 Nebula Award for Best Novel for A Game of Thrones[78]

- 1999 Nebula Award for Best Novel for A Clash of Kings

- 2001 Nebula Award for Best Novel for A Storm of Swords

- 2001 Hugo Award for Best Novel for A Storm of Swords[79]

- 2006 Hugo Award for Best Novel for A Feast for Crows [80]

- 2006 Quill Award for A Feast for Crows

- British Fantasy Award for A Feast for Crows

- 2012 Hugo Award for Best Novel for A Dance with Dragons[81]

Bibliography

Author

| Title | Year | Type | Note |

|---|---|---|---|

| A Song for Lya | 1976 | Short story collection | |

| Dying of the Light | 1977 | Novel | |

| Songs of Stars and Shadows | 1977 | Short story collection | |

| The Ice Dragon | 1980 | Young-adult fiction | |

| Windhaven | 1981 | Novel | with Lisa Tuttle |

| Sandkings | 1981 | Short story collection | |

| Fevre Dream | 1982 | Novel | |

| "In the Lost Lands" | 1982 | Short story | Amazons II anthology |

| Songs the Dead Men Sing | 1983 | Short story collection | |

| The Armageddon Rag | 1983 | Novel | |

| Nightflyers | 1985 | Short story collection | |

| Tuf Voyaging | 1986 | Fix-up novel | |

| Portraits of His Children | 1987 | Short story collection | |

| The Skin Trade | 1989 | Novella | Dark Visions compilation |

| A Game of Thrones | 1996 | Novel | A Song of Ice and Fire, book 1 |

| A Clash of Kings | 1998 | Novel | A Song of Ice and Fire, book 2 |

| The Hedge Knight | 1998 | Novella | Tales of Dunk and Egg, part 1 |

| A Storm of Swords | 2000 | Novel | A Song of Ice and Fire, book 3 |

| Quartet | 2001 | Short story collection | |

| GRRM: A RRetrospective | 2003 | Short story & essay collection | |

| The Sworn Sword | 2003 | Novella | Tales of Dunk and Egg, part 2 |

| A Feast for Crows | 2005 | Novel | A Song of Ice and Fire, book 4 |

| Hunter's Run | 2007 | Novel | with Gardner Dozois and Daniel Abraham |

| The Mystery Knight | 2010 | Novella | Tales of Dunk and Egg, part 3 |

| A Dance with Dragons | 2011 | Novel | A Song of Ice and Fire, book 5 |

| The Wit and Wisdom of Tyrion Lannister | 2013 | Quote collection | from A Song of Ice and Fire |

| The Princess and the Queen | 2013 | Novella | A Song of Ice and Fire, prequel[82] |

| The Rogue Prince | 2014 | Novella | A Song of Ice and Fire, prequel[83] |

| The World of Ice & Fire | 2014 | Reference book | The history of Westeros, with Elio M García Jr. and Linda Antonsson |

| The Ice Dragon | 2014 | Young adult illustrated novel | Reworked version of the original novel published in 1980, illustrated by Luis Royo[84] |

| A Knight of the Seven Kingdoms | 2015 | Collection | compilation of the first three Tales of Dunk and Egg[85] |

| The Winds of Winter | Forthcoming | Novel | A Song of Ice and Fire, book 6 |

| A Dream of Spring | Forthcoming | Novel | A Song of Ice and Fire, book 7 |

Television

- The Twilight Zone

- "The Last Defender of Camelot" (1986) – writer (teleplay)

- "The Once and Future King" (1986) – writer (teleplay), story editor

- "A Saucer of Loneliness" (1986) – story editor

- "Lost and Found" (1986) – writer (teleplay), from a published short story by Phyllis Eisenstein

- "The Girl I Married" (1987) – story editor

- "The World Next Door" (1989) – story editor

- "The Toys of Caliban" (1986) – writer (teleplay), from an unpublished short story by Terry Matz

- "The Road Less Traveled" (1986) – writer (story and teleplay), story editor

- Beauty and the Beast

- "Terrible Saviour" (1987) – writer

- "Masques" (1987) – writer

- "Shades of Grey" (1988) – writer

- "Promises of Someday" (1988) – writer

- "Fever" (1988) – writer

- "Ozymandias" (1988) – writer

- "Dead of Winter" (1988) – writer

- "Brothers" (1989) – writer

- "When the Blue Bird Sings' (1989) – writer (teleplay)

- "A Kingdom by the Sea" (1989) – writer

- "What Rough Beast" (1989) – writer (story)

- "Ceremony of Innocence" (1989) – writer

- "Snow" (1989) – writer

- "Beggar's Comet" (1990) – writer

- "Invictus" (1990) – writer

- The Outer Limits

- "The Sandkings" (1995) – writer (story)

- Doorways (1993, unreleased pilot) – writer, producer, creator; (IDW Publishing issued the pilot's storyline as a graphic novel miniseries in 2010)[86]

- Game of Thrones

- "Winter Is Coming" (2010) - cameo in original unaired pilot

- "The Pointy End" (2011) – writer

- "Blackwater" (2012) – writer

- "The Bear and the Maiden Fair" (2013) – writer

- "The Lion and the Rose" (2014) – writer

- Sharknado 3: Oh Hell No! (2015) - cameo

- Z Nation (2015) - cameo (zombified version of himself)

Editor

- New Voices in Science Fiction (1977: new stories by the John W. Campbell Award winners)

- New Voices in Science Fiction 2 (1979: more new stories by the John W. Campbell Award winners)

- New Voices in Science Fiction 3 (1980: more new stories by the John W. Campbell Award winners)

- New Voices in Science Fiction 4 (1981: more new stories by the John W. Campbell Award winners)

- The Science Fiction Weight Loss Book (1983) edited with Isaac Asimov and Martin H. Greenberg ("Stories by the great science fiction writers on fat, thin, and everything in between")

- The John W. Campbell Awards, Volume 5 (1984, continuation of the New Voices in Science Fiction series)

- Night Visions 3 (1986)

Wild Cards series editor (also contributor to many volumes)

- Wild Cards (1987; contents expanded in 2010 edition with three new stories/authors)

- Wild Cards II: Aces High (1987)

- Wild Cards III: Jokers Wild (1987)

- Wild Cards IV: Aces Abroad (1988; contents expanded in 2015 edition with two new stories/authors)

- Wild Cards V: Down & Dirty (1988)

- Wild Cards VI: Ace in the Hole (1990)

- Wild Cards VII: Dead Man's Hand (1990)

- Wild Cards VIII: One-Eyed Jacks (1991)

- Wild Cards IX: Jokertown Shuffle (1991)

- Wild Cards X: Double Solitaire (1992)

- Wild Cards XI: Dealer's Choice (1992)

- Wild Cards XII: Turn of the Cards (1993)

- Wild Cards: Card Sharks (1993; Book I of a New Cycle trilogy)

- Wild Cards: Marked Cards (1994; Book II of a New Cycle trilogy)

- Wild Cards: Black Trump (1995; Book III of a New Cycle trilogy)

- Wild Cards: Deuces Down (2002)

- Wild Cards: Death Draws Five (2006; solo novel by John J. Miller)

- Wild Cards: Inside Straight (2008; Book I of the Committee triad)

- Wild Cards: Busted Flush (2008; Book II of the Committee triad)

- Wild Cards: Suicide Kings (2009; Book III of the Committee triad)

- Wild Cards: Fort Freak (2011)

- Wild Cards: Lowball (2014)

- Wild Cards: High Stakes (announced; forthcoming)[87]

Cross-genre anthologies edited (with Gardner Dozois)

- Songs of the Dying Earth (2009; a tribute anthology to Jack Vance´s seminal Dying Earth series, first published by Subterranean Press)

- Warriors (2010; a massive, cross-genre anthology featuring stories about war and warriors; winner of the 2011 Locus Poll Award for Best Original Anthology)

- Songs of Love and Death (2010; a cross-genre anthology featuring stories of romance in fantasy and science fiction settings, originally entitled Star Crossed Lovers)

- Down These Strange Streets (2011; a cross-genre anthology that blends classic detective stories with fantasy and science fiction)

- Old Mars (2013; a science fiction anthology featuring all new, retro-themed stories about the Red Planet)[88]

- Dangerous Women (2013;[89] a cross-genre anthology focusing on women warriors and strong female characters, originally titled Femmes Fatale)[90]

- Rogues (2014; a cross-genre anthology featuring new stories about assorted rogues)[88]

- Old Venus (2015 publication; an anthology of all new, retro-themed Venus science fiction stories)[88][91]

References

- ^ "George R. R. Martin Webchat Transcript". Empire Online. Retrieved July 22, 2013.

- ^ "KPCS: Damon Lindelof #117". Blip.tv. June 27, 2011. Retrieved October 29, 2012.

- ^ Richards, Linda (January 2001). "January interview: George R.R. Martin". januarymagazine.com. Archived from the original on April 4, 2012. Retrieved January 21, 2012.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ Choate, Trish (September 22, 2011). "Choate: Quest into world of fantasy books can be hobbit-forming". Times Record News. Retrieved February 28, 2012.

- ^ Grossman, Lev (November 13, 2005). "Books: The American Tolkien". Time. Archived from the original on December 29, 2008. Retrieved August 2, 2014.

{{cite news}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ a b The 2011 TIME 100: George R.R. Martin, John Hodgman, April 21, 2011

- ^ The 2011 TIME 100: Full List Retrieved June 5, 2011

- ^ "Author George R.R. Martin Is Visiting Texas A&M, Talks 'Game of Thrones' and Texas A&M Libraries". TAMUTimes. Texas A&M University. March 22, 2013. Archived from the original on March 26, 2013.

- ^ "Monitor". Entertainment Weekly. No. 1277/1278. September 20–27, 2013. p. 36.

- ^ "Life & Times of George R.R. Martin". George R.R. Martin (official website). Retrieved February 27, 2012.

- ^ Martin, George R. R. (October 2004). "The Heart of a Small Boy". Asimov's Science Fiction. Archived from the original on October 19, 2004. Retrieved March 28, 2014.

- ^ "Interview with George R.R. Martin". Sea of Shelves. Retrieved October 30, 2014.

- ^ "The Heart of a Small Boy by George R. R. Martin". Retrieved October 30, 2014.

- ^ a b Berwick, Isabel (June 1, 2012). "Lunch with the FT: George RR Martin". Financial Times. Retrieved June 1, 2012.

- ^ Rutkoff, Aaron (July 8, 2011). "Garden State Tolkien: Q&A With George R.R. Martin". The Wall Street Journal. "Mr. Martin, 62 years old, says that he grew up in a federal housing project in Bayonne, which is situated on a peninsula.... 'My four years at Marist High School were not the happiest of my life,' the author admits, although his growing enthusiasm for writing comics and superhero stories first emerged during this period."

- ^ Dent, Grace (interviewer); Martin, George R. R. (June 12, 2012). Game Of Thrones – Interview with George R.R. Martin. YouTube.

- ^ Gustines, George Gene (October 3, 2014). "In the Beginning, It Was All About Comics". The New York Times. pp. C28. Retrieved July 29, 2015.

- ^ "George Stroumboulopoulos Tonight, interview with Martin". George Stroumboulopoulos Tonight. CBC.ca. March 14, 2012. Retrieved March 15, 2012.

- ^ Munson, Kyle (May 23, 2014). "Before Westeros, there was Iowa". Iowa City Press-Citizen.

- ^ "George R.R. Martin Has a Detailed Plan For Keeping the Game of Thrones TV Show From Catching Up To Him". Vanity Fair. Retrieved October 30, 2014.

- ^ "With Morning Comes Mistfall". Hugo Awards. Retrieved May 22, 2012.

- ^ "Index to SF Awards". The Locus. Retrieved August 14, 2012.

- ^ Martin, George R.R. (May 2001). "Night of the Vampyres". The Best Military Science Fiction of the 20th Century. New York: Ballantine. pp. 279–306.

{{cite news}}: Unknown parameter|editors=ignored (|editor=suggested) (help) - ^ "'Profile' George R.R. Martin". IMDB. Retrieved May 9, 2014.

- ^ Kerr, John Finlay (2009). "Second person: Role-playing and story in games and playable media". Transformative Works and Cultures (2).

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|editors=ignored (|editor=suggested) (help) doi:10.3983/twc.2009.0095 - ^ Shannon Appelcline (2011). Designers & Dragons. Mongoose Publishing. p. 87. ISBN 978-1-907702-58-7.

- ^ "Interview – George R. R. Martin – January Magazine". Retrieved October 30, 2014.

- ^ Peter Sagal (September 15, 2012). "'Thrones' Author George R.R. Martin Plays Not My Job". NPR. Retrieved September 16, 2012.

- ^ A Feast for Crows award nominations

- ^ HBO greenlights Game of Thrones to series (pic), The Hollywood Reporter, November 30, 2010

- ^ VanderMeer, Jeff (July 12, 2011). "Book review: 'A Dance With Dragons' by George R.R. Martin". Los Angeles Times.

- ^ Jennings, Dana (July 14, 2011). "In a Fantasyland of Liars, Trust No One, and Keep Your Dragon Close". New York Times.

- ^ "The American Tolkien" by Lev Grossman, a Times article on Martin. Retrieved on November 3, 2007.

- ^ a b Wagner, T. M. (2003). "A Storm of Swords / George R. R. Martin ★★★★½". sfreviews.net. Retrieved July 8, 2014.

- ^ "Review of A Game of Thrones". Archived from the original on March 25, 2008. Retrieved November 3, 2007.

- ^ Review of A Storm of Swords by Publishers Weekly

- ^ "George R R Martin". QBD The Bookshop. 2014. Retrieved July 8, 2014.

- ^ "GRRM Interview Part 2: Fantasy and History". Time. April 18, 2011.

- ^ Hobson, Anne (May 31, 2013). "Is George R.R. Martin the "American Tolkien'?". The American Spectator. Retrieved July 8, 2014.

- ^ "Quote by George R.R. Martin: "I admire Tolkien greatly..."". goodreads.com. 2014. Retrieved July 8, 2014.

- ^ Gilmore, Mikal (April 23, 2014). "'Game of Thrones' Author George R.R. Martin". Rolling Stone. Retrieved July 8, 2014.

- ^ "John Hodgman interviews George R.R. Martin". Public Radio International. September 21, 2011. Retrieved July 8, 2014.

- ^ Pasick, Adam (2014). "George R.R. Martin on His Favorite Game of Thrones Actors, and the Butterfly Effect of TV Adaptations". vulture.com. Retrieved July 8, 2014.

- ^ "Unnatural Forces: George RR Martin discusses the necessity of magic in a fantasy". YouTube. June 13, 2011. Retrieved July 8, 2014.

- ^ "William Faulkner – Banquet Speech". nobelprize.org. December 10, 1950. Retrieved July 8, 2014.

- ^ "'Game of Thrones' Author George R.R. Martin Spills the Secrets of 'A Dance with Dragons'". The Wall Street Journal. July 8, 2011.

- ^ Walter, Damien G. (July 26, 2011). "George RR Martin's fantasy is not far from reality". The Guardian. Retrieved July 8, 2014.

- ^ Poniewozik, James (April 19, 2011). "GRRM Interview Part 3: The Twilight Zone and Lost". Time.

- ^ Martin, George R R. "Social Media". Not A Blog. Retrieved May 11, 2014.

- ^ Disch, Thomas M. (2005). "The Labor Day Group" (PDF). The University of Michigan Press. Retrieved July 8, 2014.

- ^ "Tour Dates/Appearances". georgerrmartin.com. 2014. Retrieved July 8, 2014.

- ^ "Worldcon GoH Speech". asimovs.com. 2003. Retrieved September 9, 2014.

- ^ "Ansible Report". ansible.co.uk. 2003. Retrieved September 9, 2014.

- ^ "George R.R. Martin's Blog". goodreads.com. 2014. Retrieved July 8, 2014.

- ^ Miller, Laura (April 11, 2011). "Onward and Upward with the Arts: Just Write It!: A fantasy author and his impatient fans". The New Yorker. Retrieved February 12, 2012.

- ^ Kay, Guy Gavriel (April 10, 2009). "Restless readers go bonkers". Globe and Mail. Canada. Retrieved May 13, 2010.

- ^ Flood, Alison (February 16, 2010). "Excitement as George RR Martin announces he's 1,200 pages into new book". The Guardian. London. Retrieved May 13, 2010.

- ^ Gaiman, Neil (May 16, 2009). "Entitlement Issues..." Retrieved December 17, 2015.

- ^ Martin, George R R. "Frequently Asked Questions – George R. R. Martin's Official Website". Retrieved May 31, 2014.

- ^ Martin, George R R (May 7, 2010). "Not A Blog – Someone Is Angry On the Internet". LiveJournal. Retrieved January 16, 2013.

- ^ "In Love With Lisa". Life & Times. George R.R. Martin Official Website. Retrieved July 8, 2012.

- ^ Cornell, Paul (September 12, 2011). "Worldcon: A Love Story". paulcornell.com. Retrieved July 8, 2014.

- ^ Martin, George R.R. (June 16, 2014). "Not A Blog: Wolves". grrm.livejournal.com. Retrieved July 8, 2014.

- ^ Constable, Anne; Grimm, Julie Ann (April 18, 2013). "George R.R. Martin reportedly plans to revive Jean Cocteau". The Santa Fe New Mexican. Retrieved July 8, 2014.

- ^ Monroe, Rachel (February 11, 2015). "How George RR Martin is helping stem Santa Fe's youth exodus". The Guardian. Retrieved February 12, 2015.

- ^ Jardrnak, Jackie (January 29, 2015). "Silva Lanes to be transformed to an explorable art space for kids and adults". Albuquerque Journal. Retrieved February 12, 2015.

- ^ James Hibberd (July 12, 2011). "EW interview: George R.R. Martin talks 'A Dance With Dragons'". Entertainment Weekly.

- ^ "Even 'Game of Thrones' creator George R.R. Martin is ready to quit on Jets". NJ.com. Retrieved October 30, 2014.

- ^ "Ser Strike Zone: Game of Thrones author George R.R. Martin throws out the first pitch at a Minor League game". mlb.com. Retrieved March 10, 2015.

- ^ http://blogs.wsj.com/speakeasy/2014/07/29/george-r-r-martins-game-of-thrones-charity-fundraiser-draws-winner/

- ^ http://mashable.com/2014/06/05/george-r-r-martin-crowd-funding/#tQE8ca3S2aql

- ^ "George R.R. Martin On Vietnam And The Realities Of War". George Stroumboulopoulos. Retrieved October 24, 2015.

- ^ Tom Trowbridge. "Oct. 6 First News: Gubernatorial Candidates To Face-Off Tonight in Spanish-Language Debate (Listen)". Retrieved October 30, 2014.

- ^ "Jean Cocteau Get Green Light to Screen the Interview". Santa Fe New Mexican. 2014.

- ^ "My Position On the Syrian Refugees". George R. R. Martin. Retrieved December 13, 2015.

- ^ "2014 Locus Awards Winners". Locus. June 28, 2014. Retrieved September 26, 2014.

- ^ "George R. R. Martin returns to Medill - Medill - Northwestern University". Retrieved November 6, 2015.

- ^ "2004 Award Winners & Nominees". Worlds Without End. Retrieved July 25, 2009.

- ^ "2001 Hugo Awards". World Science Fiction Society. Archived from the original on May 7, 2011. Retrieved June 21, 2014.

- ^ "2006 Hugo Awards". World Science Fiction Society. Archived from the original on May 7, 2011. Retrieved June 21, 2014.

- ^ "2012 Hugo Awards". World Science Fiction Society. Archived from the original on April 9, 2012. Retrieved June 21, 2014.

- ^ "Dangerous Women: "The Princess and The Queen, or, The Blacks and The Greens" (Excerpt) by George R. R. Martin". tor.com. July 30, 2013. Retrieved July 8, 2014.

- ^ Martin, George R. R. (March 12, 2014). "Not a Blog: The Rogues Are Coming..." grrm.livejournal.com. Retrieved May 2, 2014.

- ^ "The Ice Dragon – UK cover reveal!". HarperVoyagerbooks.co.uk. Retrieved October 13, 2014.

- ^ "Not a Blog post: Dunk and Egg". George R.R. Martin. Retrieved April 14, 2014.

- ^ IDW's November Previews, "IDW Publishing", August 18, 2010

- ^ Martin, George R.R. (August 5, 2012). "Flying High with Wild Cards". Not A Blog. Retrieved July 8, 2014.

- ^ a b c Martin, George R.R. (May 12, 2012). "Odds and Ends". Not A Blog. Retrieved July 8, 2014.

- ^ "Dangerous Women Arrives on Tor.com". Tor.com. July 24, 2013. Retrieved November 19, 2013.

- ^ Martin, George R.R. (July 2, 2011). "Stuff and Nonsense". Not A Blog. Retrieved July 8, 2014.

- ^ Martin, George R.R. (June 16, 2014). "Venus In March". Not A Blog. Retrieved July 8, 2014.

External links

- Official website

- George R. R. Martin at IMDb

- George R. R. Martin at the Internet Book List

- George R. R. Martin at the Internet Speculative Fiction Database

- Template:Worldcat id

- Martin's awards and nominations at The Locus Index to Science Fiction Awards.

- 1948 births

- Living people

- 20th-century American novelists

- 21st-century American novelists

- A Song of Ice and Fire

- Game of Thrones (TV series)

- American agnostics

- American bloggers

- American conscientious objectors

- American entertainment industry businesspeople

- American fantasy writers

- American horror writers

- American science fiction writers

- American short story writers

- American television producers

- American television writers

- American people of English descent

- American people of French descent

- American people of German descent

- American people of Irish descent

- American people of Italian descent

- Hugo Award-winning writers

- Nebula Award winners

- New Mexico Democrats

- Male television writers

- Medill School of Journalism alumni

- People from Bayonne, New Jersey

- Writers from Santa Fe, New Mexico

- People from Bernalillo County, New Mexico

- Science fiction fans

- VISTA volunteers

- Writers from New Jersey

- Former Roman Catholics

- Clarke University faculty and staff

- Theatre owners

- American male novelists

- American male screenwriters

- American male short story writers