Georgia Tech: Difference between revisions

Undid revision 306435859 by 97.89.26.255 (talk) - rm drum major |

No edit summary |

||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

{{Infobox_University |

{{Infobox_University |

||

|name = Georgia Institute of |

|name = Georgia Institute of echnology |

||

|nickname =Yellow Jackets, Ramblin' Wreck |

|nickname =Yellow Jackets, Ramblin' Wreck |

||

|image_name = Georgia-Tech-Insignia.svg |

|image_name = Georgia-Tech-Insignia.svg |

||

Revision as of 20:15, 6 August 2009

The Georgia Institute of Technology, commonly called Georgia Tech, Tech, and GT, is a public, coeducational research university in Atlanta, Georgia in the United States. A part of the University System of Georgia, it also has satellite campuses in Savannah, Georgia; Metz, France; Athlone, Ireland; Shanghai, China; and Singapore.

The educational institution was founded in 1885 as the Georgia School of Technology as part of Reconstruction plans to build an industrial economy in the post-Civil War Southern United States. Initially it offered a degree in mechanical engineering only. By 1901, its curriculum had expanded to include electrical, civil, and chemical engineering. In 1948, the school changed its name to reflect its evolution from a trade school to a larger and more capable technical institute and research university. Today, Georgia Tech is organized into six colleges, containing about 31 departments/units, with a strong emphasis on science and technology. It is well recognized for its programs in engineering, computing, and the sciences, and offers degrees in architecture, liberal arts, and management.

Georgia Tech's main campus occupies a large part of Midtown Atlanta, bordered by 10th Street to the north and by North Avenue to the south, placing it well in sight of the Atlanta skyline. In 1996, the campus was the site of the athletes' village and a venue for a number of athletic events for the 1996 Summer Olympics. Whereas, previously, the Midtown location placed Georgia Tech students in the middle of one of the highest metropolitan crime-rate areas in America, the construction of the Olympic village along with subsequent gentrification of the surrounding areas greatly increased public safety.

Student athletics, both organized and intramural, are an important part of student and alumni life. The school's intercollegiate competitive sports teams, the Yellow Jackets, and the nationally recognized fight song "Ramblin' Wreck from Georgia Tech", have helped keep Georgia Tech in the national spotlight.

History

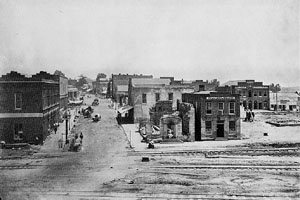

Establishment

The idea of Georgia Institute of Technology was introduced in 1865 during the Reconstruction period. Two former Confederate officers, Major John Fletcher Hanson and Nathaniel Edwin Harris, who had become prominent citizens in the town of Macon, Georgia after the Civil War, strongly believed that the South needed to improve its technology to compete with the industrial revolution that was occurring throughout the North.[7][8] Many Southerners at this time agreed with this idea. However, because the American South of that era was mainly populated by agricultural workers and few technical developments were occurring, a technology school was needed.[7][8]

In 1882, prominent Georgians, authorized by the Georgia State Legislature and led by Harris, formed a committee and visited the Northeast to see firsthand how technology schools worked. Using examples from the Worcester County Free Institute of Industrial Science (now Worcester Polytechnic Institute) and the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, the Atlanta technology school began development on the Worcester Free Institute model, which stressed a combination of "theory and practice", the "practice" component including student employment and production of consumer items to generate revenue for the school.[9]

On October 13, 1885, Georgia Governor Henry D. McDaniel signed the bill to create and fund the new school.[1] In 1887, Atlanta pioneer Richard Peters donated 4 acres (1.6 ha) of his extensive land holdings to the state;[1] this land was bounded on the south by North Avenue, and on the west by Cherry Street.[1] He then sold five adjoining acres of land to the state for US$10,000,[1] equivalent to about US$Error when using {{Inflation}}: |end_year=2,024 (parameter 4) is greater than the latest available year (2,023) in index "US". now. This land was located near the northern city limits of Atlanta at the time of its founding, although the city has now expanded several miles (kilometers) beyond it. A historical marker on the large hill in Central Campus notes that the site occupied by the school's first buildings once held fortifications built to protect Atlanta during the Atlanta Campaign of the American Civil War. The surrender of the city took place on the southwestern boundary of the modern Georgia Tech campus in 1864.[10]

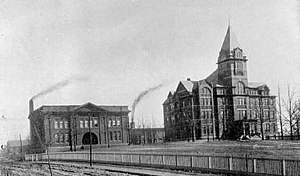

Early years

The Georgia School of Technology opened its doors in the fall of 1888 with only two buildings.[7] One building (now Tech Tower, an administrative headquarters) had classrooms to teach students; The second building featured a shop and had a foundry, forge, boiler room, and engine room. It was designed specifically for students to work and produce goods to sell and fund the school. The two buildings were equal in size to show the importance of teaching both the mind and the hands;[7] though, at the time, there was some disagreement to whether the machine shop should have been used to turn a profit.[9]

On October 20, 1905, U.S. President Theodore Roosevelt visited the Georgia Tech campus. On the steps of Tech Tower, Roosevelt delivered a speech about the importance of technological education.[11] He then shook hands with every student.[12]

Georgia Tech's Evening School of Commerce began holding classes in 1912.[13] The evening school admitted its first female student in 1917, although the state legislature did not officially authorize attendance by women until 1920.[13][14] Annie T. Wise became the first female graduate in 1919 and went on to become Georgia Tech's first female faculty member the following year.[13][14] In 1931, the Board of Regents transferred control of the Evening School of Commerce to the University of Georgia (UGA) and moved the civil and electrical engineering courses at UGA to Tech.[13][14] Tech replaced the commerce school with what later became the College of Management. The commerce school would later split from UGA and eventually become Georgia State University.[13][15] In 1934, the Engineering Experiment Station (later known as the Georgia Tech Research Institute) was founded by W. Harry Vaughan with an initial budget of $5000 ($Error when using {{Inflation}}: |end_year=2,024 (parameter 4) is greater than the latest available year (2,023) in index "US". today) and 13 part-time faculty.[16][17]

Modern history

Founded as the Georgia School of Technology, it assumed its present name in 1948 to reflect a growing focus on advanced technological and scientific research.[18] Unlike similarly-named universities (such as the Massachusetts Institute of Technology and the California Institute of Technology), the Georgia Institute of Technology is a public institution.

Tech first admitted female students to regular classes in 1952,[19] although women could not enroll in all programs at Tech until 1968. Industrial Management was the last program to open to women.[13][19] The first women's dorm, Fulmer Hall, opened in 1969.[13] Women constituted 30.3% of the undergraduates and 25.3% of the graduate students enrolled in Spring 2009.[20] In 1959, a meeting of 2,741 students voted by an overwhelming majority to endorse integration of qualified applicants, regardless of race.[21] Three years after the meeting, and one year after the University of Georgia's violent integration,[21] Georgia Tech became the first university in the Deep South to desegregate without a court order.[22] There was little reaction to this by Tech students; like the city of Atlanta described by former mayor William Hartsfield, they seemed "too busy to hate".[21]

John Patrick Crecine was instrumental in securing the 1996 Summer Olympics for Atlanta. A dramatic amount of construction occurred, creating most of what is now considered "West Campus" in order for Tech to serve as the Olympic Village, and significantly gentrifying Midtown Atlanta.[23][24] The Undergraduate Living Center, Fourth Street Apartments, Sixth Street Apartments, Eighth Street Apartments, Hemphill Apartments, and Center Street Apartments housed athletes and journalists. The Georgia Tech Aquatic Center was built for swimming events, and the Alexander Memorial Coliseum was renovated.[13][24] The Institute also erected the Kessler Campanile and fountain to serve as a landmark and symbol of the Institute on television broadcasts.[13] Since then, the Campanile has come to be known by students as "The Shaft".[25]

In 1994, G. Wayne Clough became the first Tech alumnus to serve as the President of the Institute; he was in office during the 1996 Summer Olympics. In 1998, he separated the Ivan Allen College of Management, Policy, and International Affairs into the Ivan Allen College of Liberal Arts and returned the College of Management to "College" status. (Crecine, the previous president, had demoted Management from "College" to "School" status as part of a controversial 1990 reorganization plan.)[26][27] His tenure has been focused on a dramatic expansion of the institute, a revamped Undergraduate Research Opportunities Program, and the creation of an International Plan.[28][29] On March 15, 2008, he was appointed to lead the Smithsonian Institution, effective July 1, 2008.[30] Dr. Gary Schuster, Tech's Provost and Executive Vice President for Academic Affairs, was named Interim President, effective July 1, 2008.[31] On April 1, 2009, George P. "Bud" Peterson, previously the chancellor of the University of Colorado at Boulder, became the 11th president of Georgia Tech.[4]

Academics

Demographics

The student body consists of 18,000 graduate and undergraduate students (Spring 2009) and more than 900 full-time instructional faculty (October 2008).[6][5][32] Historically, female enrollment at engineering institutions has been quite low and Georgia Tech is no exception. With about twice as many male students as females, Georgia Tech has one of the most unbalanced male-to-female ratios of any co-ed university. However, this is slowly changing due to the university's growing liberal arts programs and outreach programs to encourage more female high school students to consider careers in science and engineering. These include the "Women In Engineering" program and sponsorship of a chapter of The Society of Women Engineers.[33][34] As of Spring 2009[update], the freshman class of 2008–2009 had a ratio of 67.4% to 32.2%.[35] The highest freshman ratio in the past few years (counting only Fall and Spring semesters)[36] was Spring 2006, with a ratio of 70.5% to 29.5%.[35]

Funding

The Georgia Institute of Technology is a public institution that receives funds from the State of Georgia, tuition, fees, research grants, and alumni contributions. In 2008, the Institute's revenue amounted to about $1.051 billion, with 26% of that amount from the state and 13% from tuition and fees.[37] Most of the remaining funds were donated by private sources, including the most generous alumni donor base, percentage-wise, of any public university ranked in the top 50.[38] The Institute's expenses for 2008 were $1.006 billion; 42% of that figure went to research and 21% to instruction.[39]

Rankings

Georgia Tech is consistently ranked well; it has remained in the top ten public universities in the United States for the last ten years.[40] In 2008, U.S. News & World Report ranked Tech as the No. 7 public university, and No. 35 among all universities.[40] Tech also has the No. 4 undergraduate engineering program, and the No. 4 graduate engineering program.[40] Highly ranked engineering programs include its Schools of Industrial Engineering (1st), Biomedical (3rd), Mechanical (3rd), Aerospace (2nd), Electrical (4th), and Civil Engineering (4th) at the undergraduate level[40] and Industrial Engineering (1st), Biomedical (2nd), and Aerospace (2nd) at the graduate level.[41] In 2007, THE - QS World University Rankings ranked Georgia Tech as the No. 8 university in technology[42] and as No. 83 overall.[43] Diverse Issues in Higher Education has ranked Tech No. 1 at the bachelor's level, No. 2 at the master's level, and No. 1 at the doctoral level in terms of producing African American engineering graduates.[32]

Colleges

Georgia Tech's undergraduate and graduate programs are divided into six Colleges. Collaboration among the Colleges is frequent, as mandated by a number of interdisciplinary degree programs and research centers.[44] Georgia Tech has sought to strengthen its undergraduate and graduate offerings in less technical fields, primarily those under the Ivan Allen College of Liberal Arts. That particular college has seen a 20% increase in admissions.[45] Also, even in the Ivan Allen College, the Institute does not offer a Bachelor of Arts degree, only a Bachelor of Science.

Research

Georgia Tech is currently classified by The Carnegie Foundation for the Advancement of Teaching as a university with very high research activity.[46] Much of this research is funded by large corporations or governmental organizations.[47] In addition to research performed by its academic units, Georgia Tech is affiliated with a nonprofit research organization referred to as the Georgia Tech Research Institute (GTRI).[48] GTRI provides sponsored research in a variety of technical specialties including radar, electro-optics, and materials engineering.[48] Forty percent of Georgia Tech's research, especially government-funded classified work, is conducted through this counterpart organization.[47] GTRI employs over 1,300 people, conducting over $110 million in research every year.[48]

Many startup companies are produced through research conducted at Georgia Tech, with the Advanced Technology Development Center and VentureLab ready to assist Georgia Tech's researchers and entrepreneurs in organization and commercialization. The Georgia Tech Research Corporation serves as Georgia Tech's contract and technology licensing agency. Georgia Tech is ranked fourth for startup companies, eighth in patents, and eleventh in technology transfer.[47][49] 1,900,000 square feet (180,000 m2) of space are devoted to research purposes at Georgia Tech and GTRI.[47] An upcoming addition to that space will be Georgia Tech's Marcus Nanotechnology Research Center,[50] which upon completion will be the largest clean room in the Southeastern United States.

Georgia Tech encourages undergraduates to participate in research alongside graduate students and faculty. The Undergraduate Research Opportunities Program awards scholarships each semester to undergraduates who pursue research activities. These scholarships, called the President's Undergraduate Research Awards, take the form of student salaries or help cover travel expenses when students present their work at professional meetings.[51] Additionally, undergraduates may participate in research and write a thesis to earn a "Research Option" credit on their transcripts.[52] An undergraduate research journal, The Tower, was established in 2007 to provide undergraduates with a venue for disseminating their research and a chance to become familiar with the academic publishing process.[53]

Industry connections

Owing to its roots as a trade school, Georgia Tech maintains close ties to the industrial world. Many of these connections are made through Georgia Tech's uniquely popular and robust cooperative education and internship programs. Georgia Tech's Division of Professional Practice (DoPP), established in 1912 as the Georgia Institute of Technology Cooperative Division,[54] operates the fourth-oldest cooperative education program in the United States.[55] The DoPP is specifically charged with providing opportunities for students to gain real-world employment experience through four programs, each targeting a different body of students. The Undergraduate Cooperative Education Program is a five-year program in which undergraduate students alternate between semesters of formal instruction at Georgia Tech and semesters of full-time employment with their employers. The Graduate Cooperative Education Program, established in 1983, is the largest such program in the United States.[56] It allows graduate students pursuing master's degrees or doctorates in any field to spend a maximum of two consecutive semesters working full- or part-time with employers. The Undergraduate Professional Internship Program enables undergraduate students—typically juniors or seniors—to complete a one- or two-semester internship with employers. The Work Abroad Program hosts a variety of cooperative education and internship experiences for upperclassmen and graduate students seeking international employment and cross-cultural experiences. While all four programs are voluntary, they consistently attract high numbers of students—more than 3,000 at last count. Around 1,000 businesses and organizations hire these students, who collectively earn $20 million per year.[55]

Georgia Tech's cooperative education and internship programs have been externally recognized for their strengths. The Undergraduate Cooperative Education was recognized by U.S. News & World Report as one of the top 10 "Programs that Really Work" for five consecutive years.[57] U.S. News & World Report additionally ranked Georgia Tech's internship and cooperative education programs among 14 "Academic Programs to Look For" in 2006 and 2007.[38] On June 4, 2007, the University of Cincinnati inducted Georgia Tech into its Cooperative Education Hall of Honor.[58]

Student life

Georgia Tech students benefit from many Institute-sponsored or Institute-related events on campus, as well as a wide selection of cultural options in the surrounding district of Midtown Atlanta, "Atlanta's Heart of the Arts".[59] Just off campus, students can choose from a host of restaurant and dining choices typical of metropolitan areas, including a half-dozen in Technology Square alone.[60][61] Home Park, a neighborhood that borders the north end of campus, is a popular living area for Tech students and recent graduates,[62] and a number of parties and barbecues are hosted by the neighborhood's residents.[63]

Recreation and stress

A number of extracurricular activities are available to students, including over 350 student organizations overseen by the Office of Student Involvement.[64] The Student Government Association (SGA), Georgia Tech's form of student government, comprising separate executive, legislative, and judicial branches for undergraduate and graduate students.[65] One of the SGA's primary duties is the disbursement of funds to student organizations in need of financial assistance. These funds are derived from the student activity fee that all Georgia Tech students must pay, currently $118 per semester. The ANAK Society, a secret society and honor society established at Georgia Tech in 1908, claims responsibility for founding many of Georgia Tech's earliest traditions and oldest student organizations, including the SGA.[66] Nearly 50 fraternities and sororities are active on Georgia Tech's campus, and about a third of Tech undergraduates participate in one of them.[67]

Despite these offerings, Georgia Tech carries a strong reputation for being more of a test of spirit than an enjoyable life experience. In 2001, The Princeton Review placed Tech among the 10 toughest colleges and universities in the United States[68] and later reported that Tech's heavy workload led to "overly stressed" students with "minimal time for social functions".[69] In 2002, the Review ranked Tech No. 2 on its list of colleges and universities with the "least happy students",[70] prompting Institute officials to publish a report the following year responding to the negative publicity. The report criticized the Review for the lack of scientific rigor in its methods and referred to data from internal opinion surveys demonstrating increased student satisfaction in several areas.[71] Among students, it is widely believed that a sacrifice of sleep, studying, or a social life defines "the Tech lifestyle".[72] For these reasons, students commonly refer to graduation from Tech simply as "getting out".[25]

Housing

Georgia Tech Housing is generally split into two parts, East Campus and West Campus. East Campus is largely populated by freshmen and is served by Brittain Dining Hall. West Campus houses some freshmen, transfer, and returning students, and is served by Woodruff Dining Hall.[73][74]

The Institute's administration has implemented programs to reduce the levels of stress and anxiety felt by Tech students. The Familiarization and Adaptation to the Surroundings and Environs of Tech (FASET) Orientation and Freshman Experience (a freshman-only dorm life program to "encourage friendships and a feeling of social involvement") programs, which seek to help acclimate new students to their surroundings and foster a greater sense of community.[75][76] As a result, the Institute's retention rates have improved.[77]

In recent years, Georgia Tech Housing has been at or over capacity.[78] In Fall 2006, many dorms housed "triples", which was a project that put three residents into a two-person room. Certain pieces of furniture were not provided to the third resident as to accommodate a third bed. When spaces became available in other parts of campus, the third resident was moved elsewhere.[79][80][81][82]

In the fall of 2007, the North Avenue Apartments were opened to Tech students. Originally built for the 1996 Olympics and belonging to Georgia State University, the buildings were gifted to Georgia Tech and have been used to accommodate Tech's expanding population, although Georgia Tech freshmen students were the first to inhabit the dormitories in the Winter and Spring 1996 quarters, while much of East Campus was under renovation for the Olympics. The North Avenue Apartments (commonly known as "North Ave") are also noted as the first Georgia Tech buildings to rise above the top of Tech Tower. Open to second-year undergraduate students and above, the buildings are located on East Campus, across North Avenue and near Bobby Dodd Stadium, putting more upperclassmen on East Campus.[83] Currently, the North Avenue Apartments East and North buildings are undergoing extensive renovation to the façade. During their construction, the bricks were not properly secured and thus were a safety hazard to pedestrians and vehicles on the Downtown Connector below.[84]

Two programs on campus as well have houses on East Campus: the International House (commonly referred to as the I-House); and Women, Science, and Technology. The I-House is housed in 4th Street East and Hayes. Women, Science, and Technology is housed in Golden and Stein. The I-House hosts an International Coffee Hour every Monday night that class is in session from 6-7 pm, hosting both residents and their guests for discussions.[85]

Traditions

Tech has a number of legends and traditions, some of which have persisted for decades. Some are well-known; for example, the most notable of these is the popular but rare tradition of stealing the 'T' from Tech Tower. Tech Tower, Tech's historic primary administrative building, has the letters "TECH" hanging atop it on each of its four sides. A number of times, students have orchestrated complex plans to steal the huge symbolic letter T, and on occasion have carried this act out successfully. The latest instance of this tradition occurred in October 2005, when a replica of the T was stolen from the Student Services Building and returned two days later.[86] One of the cherished holdovers from Tech's early years, a steam whistle blows five minutes before the hour, every hour from 7:55 a.m. to 5:55 p.m.[87] It is for that reason that the faculty newspaper is named The Whistle.[25]

Georgia Tech holds a heated, long and ongoing rivalry with the University of Georgia, known as Clean, Old-Fashioned Hate. The first known hostilities between the two institutions trace back to 1891. The University of Georgia's literary magazine proclaimed UGA's colors to be "old gold, black, and crimson". Dr. Charles H. Herty, the first UGA football coach, felt that old gold was too similar to yellow and that it "symbolized cowardice". After the 1893 football game against Tech, Herty removed old gold as an official color.[88][89] Tech would first use old gold for their uniforms, as a proverbial slap in the face to UGA, in their first unofficial football game against Auburn in 1891.[90] Georgia Tech's school colors would henceforth be old gold and white.

Arts

Founded in 1906, the Glee Club was one of the first student organizations on campus, and still operates today.[91][92] The Glee Club was among the first collegiate choral groups to release a recording of their songs. The group has toured extensively and appeared on The Ed Sullivan Show twice, providing worldwide exposure to "Ramblin' Wreck from Georgia Tech".[93][94]

The Georgia Tech Athletic Bands play a noticeable part for school spirit and athletic support.[95] It was founded in 1908 by 14 Students and Robert "Biddy" Bidez.[92] The Marching Band consistently fields over 300 members and even invites students from other Atlanta universities who do not have football programs (Georgia State University, Emory, Agnes Scott, Kennesaw State, etc) to participate. Members of the marching band travel to every football game. Since its inception in 1996, the Georgia Tech Symphony Orchestra has grown from a dozen interested students into an 80- to 90-member ensemble.[92][96]

In 1963, the Music Department, under the leadership of Ben Logan Sisk, was created within Tech's General College. In 1976 the Music department was assigned to the College of Sciences & Liberal Studies, and in 1991 was relocated to its current home in the College of Architecture. Under the Couch is a live music venue located beneath the Couch Building on West Campus. It is run by the Musician's Network. Georgia Tech also has a growing music scene, including the growing student-led a cappella groups on campus: Nothin' but Treble,[97] Sympathetic Vibrations,[98] and Infinite Harmony.[99]

Many music, theatre, dance, and opera performances are held in the Ferst Center for the Arts.[100] DramaTech is the campus' student-run theater. The theater has been entertaining Georgia Tech and the surrounding community since 1947. They are also home to Let's Try This! (the campus improv troupe) and VarietyTech (a song and dance troupe). Momocon is an annual anime/gaming/comics convention held on campus in March hosted by Anime O-Tekku, the Georgia Tech anime club. It is free admission and usually held in the Student Center and Instructional Center, as well as outdoor areas.[101]

Student media

WREK, 91.1 MHz is known as "Wreck Radio". The studio is on the second floor of the Student Center Commons. Broadcasting with 40 kW ERP, WREK is among the nation's most powerful college radio stations. WREK is a student operated and run radio station. In April 2007, a debate was held regarding the future of the radio station. The prospective purchasers were GPB and NPR. WREK maintained its independence after dismissing the notion with approval from the Radio Communications Board of Georgia Tech.[102][103][104]

The Technique, also known as the "'Nique", is Tech's official student newspaper. It is distributed weekly during the Fall and Spring semesters (on Fridays), and biweekly during the Summer semester (with certain exceptions). It was established on November 17, 1911. The Blueprint is Tech's yearbook, established in 1908.[105] Other student publications include The North Avenue Review, Tech's "free-speech magazine",[106][107] and Erato, Tech's literary magazine.[108] The offices of all student publications are located in the Student Services Building.[105][109]

Greek life

Greek life at Georgia Tech includes 48 active chapters of social fraternities and sororities.[110] All of the groups are chapters of national organizations, including members of the North-American Interfraternity Conference, National Panhellenic Conference, and National Pan-Hellenic Council. The first Greek letter fraternities to charter at the Institute were Alpha Tau Omega in 1898 and Sigma Alpha Epsilon in 1899.[110] Students with Greek affiliation make up around 21 percent of the undergraduate student body.[111]

Campus services

Georgia Tech Cable Network, or GTCN, is the college's branded cable source. The station broadcasts WREK-FM on channel 17, in addition to student-generated content and recent movies on channels 20 and 21. Most non-original programming is obtained from Dish Network. GTCN currently has 109 standard-definition channels and five high-definition channels.[112]

The Office of Information Technology, or OIT, manages most of the Institute's computing resources (and some related services such as campus telephones). With the exception of a few computer labs maintained by individual colleges, OIT is responsible for most of the computing facilities on campus. Student, faculty, and staff e-mail accounts are among its services.[113] Georgia Tech's ResNet provides free technical support to all students and guests living in Georgia Tech's on-campus housing (excluding fraternities and sororities). ResNet is responsible for network, telephone, and television service, and most support is provided by part-time student employees.[114]

Crime

Minor crimes around Georgia Tech are commonplace, a reflection of the Institute's densely-populated urban surroundings. The campus is patrolled by the Georgia Tech Police Department, whose Patrol Division comprises 60 officers.[115] The most common crime reported over the last few years, by a large margin, is larceny.[116] Between 2004 and 2006, there were only 32 violent crimes reported, most of them robberies.[116] Although the crime rate in Atlanta during the late 1980s and 1990s was the highest in the nation,[117] it has been declining since the late 1960s and the city now is the seventeenth most-dangerous city in the U.S.[118][119] The construction of large projects such as the Olympic Village and Technology Square have contributed to reduced crime rates by gentrifying the surrounding area.[23][120]

Campuses

The Georgia Tech campus is located in Midtown, an area north of downtown Atlanta. Although a number of skyscrapers — most visibly the headquarters of AT&T, The Coca-Cola Company, and Bank of America — are visible from all points on campus, the campus itself has few buildings over four stories and has a great deal of greenery. This gives it a distinctly suburban atmosphere quite different from other Atlanta campuses such as that of Georgia State University.[121][122]

The campus is organized into four main parts: West Campus, East Campus, Central Campus, and Technology Square. West Campus and East Campus are both occupied primarily by student living complexes, while Central Campus is reserved primarily for teaching and research buildings.[121]

West Campus

West Campus is occupied primarily by apartments and coed undergraduate dormitories. Prominent apartments include Hemphill, Center Street, 6th Street, Maulding, Undergraduate Living Center (ULC), and Eighth Street Apartments. Prominent dorms include Freeman, Montag, Fitten, Folk, Caldwell, Armstrong, Hefner, Fulmer, and Woodruff Suites.[121] The Campus Recreation Center (formerly the Student Athletic Complex); a volleyball court; a large, low natural green area known as the Burger Bowl; and a flat artificial green area known as the CRC (formerly SAC) Fields are all located on the western side of the campus. Also within walking distance of West Campus is City Cafe, which is open 24 hours, Rocky Mountain Pizza, and Engineer's Bookstore, an alternative to Georgia Tech's official bookstore.[123] West Campus is also home to a music club operated by students called Under the Couch as well as a convenience store, West Side Market. Due to limited space, all auto travel proceeds via a network of one-way streets which connects West Campus to Ferst Drive, the main road of the campus. Woodruff Dining Hall, or "Woody's," is the West Campus Dining Hall.[73] It connects the Woodruff North and Woodruff South undergraduate dorms.

East Campus

East Campus houses all of the fraternities and sororities as well as most of the undergraduate freshman dormitories. Although the residences are similar, East Campus is more urban than West Campus. East Campus abuts on the Downtown Connector, granting residences quick access to Midtown and its businesses (for example, The Varsity) via a number of bridges over the highway as well as a tunnel beneath it. Georgia Tech football's home, Bobby Dodd Stadium is located on East Campus, as well as Georgia Tech basketball's home Alexander Memorial Coliseum.[121] Brittain Dining Hall is the main dining hall for East Campus. It is modeled after a medieval church, complete with carved columns and stained glass windows showing symbolic figures.[73] The main road leading from East Campus to Central Campus is an ascending incline commonly known as "Freshman Hill" (in reference to the large number of freshman dorms near its foot) or simply "The Hill." On March 8, 2007, the former Georgia State University Village apartments were transferred to Georgia Tech. Renamed North Avenue Apartments by the institute, they began housing students in the fall semester of 2007.[83]

Central Campus

Central Campus is home to the majority of the academic, research, and administrative buildings. The Central Campus includes, among others: the Howey Physics Building; the Boggs Chemistry Building; the College of Computing Building; the Klaus Advanced Computing Building; the College of Architecture Building; the Skiles Classroom Building, which houses the School of Mathematics and the School of Literature, Communication and Culture; the D. M. Smith Building, which houses the School of Public Policy and the School of History, Technology, and Society; and the Ford Environmental Science & Technology Building.[121] In 2005, the School of Modern Languages returned to the Swann Building, a 100-year-old former dormitory that now houses some of the most technology-equipped classrooms on campus.[124][125] Intermingled with these are a variety of research facilities, such as the Centennial Research Building, the Microelectronics Research Center, the Nanotechnology Research Center, and the Petit Biotechnology Building.

Tech's administrative buildings, such as Tech Tower, and the Bursar's Office, are also located on the Central Campus, in the recently-renovated Georgia Tech Historic District.[126][127] The campus library, plus a small traditional eatery called Junior's Grill, the Fred B. Wenn Student Center, and the Student Services Building ("Flag Building") are also located on Central Campus. The Student Center provides a variety of recreational and social functions for students including: a computer lab, a game room ("Tech Rec"),[128] the Student Post Office, a darkened Music Listening Room, a movie theater, the Food Court, plus meeting rooms for various clubs and organizations. Adjacent to the eastern entrance of the Student Center is the Kessler Campanile (which is referred to by students as "The Shaft").[25] The former Hightower Textile Engineering building was demolished in 2002 to create Yellow Jacket Park. More greenspace now occupies the area around the Kessler Campanile for a more aesthetically pleasing look, in accordance with the official Campus Master Plan.[129] In 2008, construction began on the G. Wayne Clough Undergraduate Learning Commons, which will be located next to the library and occupy at least part of the Yellow Jacket Park area.[130]

Technology Square

Technology Square, also known as "Tech Square," is located across the Downtown Connector and embedded in the city east of East Campus.[131] Connected by the recently-renovated Fifth Street Bridge, it is a pedestrian-friendly area comprising Georgia Tech facilities and retail locations.[120][132] One complex contains the College of Management Building, holding classrooms and office space for the College of Management, as well as the Georgia Tech Hotel and Conference Center and the Georgia Tech Global Learning Center.[133] Another part of Tech Square, the privately owned Centergy One complex, contains the Technology Square Research Building (TSRB), holding faculty and graduate student offices for the College of Computing as well as the GVU Center, a multidisciplinary technology research center.[120]

Other Georgia Tech-affiliated buildings in the area host the Center for Quality Growth and Regional Development, the Georgia Tech Enterprise Innovation Institute, the Advanced Technology Development Center, VentureLab, and the Georgia Electronics Design Center. Technology Square also hosts a variety of restaurants and businesses, including the official Institute bookstore, a Barnes & Noble bookstore.[134] Opened in August 2003 at a cost of $179 million, the district was built over run-down neighborhoods and has sparked a revitalization of the entire Midtown area.[120][134][135]

Satellite campuses

In 1999, Georgia Tech began offering local degree programs to engineering students in Southeast Georgia, and in 2003 established a physical campus in Savannah, Georgia.[136] Georgia Tech Savannah offers undergraduate and graduate programs in engineering, and boasts a robust research program with many activities centered on coastal concerns. It is also home to the regional offices of the Georgia Tech Economic Development Institute and the Advanced Technology Development Center.[137] The Georgia Tech Savannah campus offers engineering programs in conjunction with Georgia Southern University, South Georgia College, Armstrong Atlantic State University, and Savannah State University.[138] The university further collaborated with the National University of Singapore to set up The Logistics Institute - Asia Pacific in Singapore.[138]

Georgia Tech also operates a campus in Metz, in northeastern France, known as Georgia Tech Lorraine. Opened in October 1990, it offers master's-level courses in Electrical and Computer Engineering, Computer Science and Mechanical Engineering and Ph.D. coursework in Electrical and Computer Engineering and Mechanical Engineering.[139] Georgia Tech Lorraine is known for a much-publicized lawsuit pertaining to the language used in advertisements; see Toubon Law.[140]

The College of Architecture maintains a small permanent presence in Paris, France in affiliation with the École d'architecture de Paris-La Villette and the College of Computing has a similar program with the Barcelona School of Informatics at the Polytechnic University of Catalonia in Barcelona, Spain. There are additional programs in Athlone, Ireland, Shanghai, China, and Singapore.[141][142] Georgia Tech will set up two campuses for research and graduate education in the cities of Visakhapatnam and Hyderabad, Andhra Pradesh, India by the year 2010.[143][144][145][146]

Athletics

Georgia Tech's sports teams are variously called the Yellow Jackets, the Ramblin' Wreck, and the Engineers, but the official nickname is Yellow Jackets. They participate in National Collegiate Athletic Association (NCAA) Division I within the Atlantic Coast Conference. The college was a charter member of the Southeastern Conference, and played in that league until 1964. The Institute mascots are Buzz and the Ramblin' Wreck. The Institute's traditional football rival is the University of Georgia; the rivalry was, at one time, considered one of the fiercest in college football. The rivalry is commonly referred to as Clean, Old-Fashioned Hate, which is also the title of a book about the subject.[147] Tech has seventeen varsity sports: football, women's and men's basketball, baseball, softball, volleyball, golf, men's and women's tennis, men's and women's swimming and diving, men's and women's track and field, and men's and women's cross country. Four Georgia Tech football teams were selected as national champions in news polls: 1917, 1928, 1952, and 1990. In May 2007, the women's tennis team won the NCAA National Championship with a 4–2 victory over UCLA, the first ever national title granted by the NCAA to Tech.[148][149]

Fight songs

Tech's fight song "I'm a Ramblin' Wreck from Georgia Tech" is known worldwide. First published in the 1908 Blue Print,[150] it was adapted from an old drinking song ("Son of a Gambolier")[150] and embellished with trumpet flourishes by Frank Roman.[151] Then-Vice President Richard Nixon and Soviet premier Nikita Khrushchev sang the song together when they met in Moscow in 1958 to reduce the tension between them.[150][152] As the story goes, Nixon did not know any Russian songs, but Khrushchev knew that one American one as it had been sung on The Ed Sullivan Show.[150]

"I'm a Ramblin' Wreck" has had many other notable moments in its history. It is reportedly the first school song to have been played in space.[153] Gregory Peck sang the song while strumming a ukulele in the movie The Man in the Gray Flannel Suit. John Wayne whistled it in The High and the Mighty. Tim Holt's character sings a few bars of it in the movie His Kind of Woman. There are numerous stories of commanding officers in Higgins boats crossing the English Channel on the morning of D-Day leading their men in the song to calm their nerves.[153] It is played after every Georgia Tech score in a football game.[150]

Another popular fight song is "Up with the White and Gold", which is usually played by the band preceding "Ramblin' Wreck". First published in 1919, "Up with the White and Gold" was also written by Frank Roman. The song's title refers to Georgia Tech's school colors and its lyrics contain the phrase, "Down with the Red and Black," an explicit reference to the school colors of the University of Georgia and the then-budding Georgia Tech–UGA rivalry.[153][154]

Club sports

Georgia Tech participates in many non-NCAA sanctioned club sports. These sports include and are not limited to crew, cricket, cycling (winning three consecutive Dirty South Collegiate Cycling Conference mountain bike championships), equestrian, fencing, field hockey, gymnastics, ice hockey, kayaking, lacrosse, paintball, roller hockey, soccer, rowing, rugby union, sailing, skydiving, table tennis, triathlon, ultimate, water polo, water ski, and wrestling. Many club sports take place at the Georgia Tech Aquatic Center, where swimming, diving, water polo, and the swimming portion of the modern pentathlon competitions for the 1996 Summer Olympics were held.[155]

Alumni

There are many notable graduates, non-graduate former students and current students of Georgia Tech. Georgia Tech alumni are generally known as Yellow Jackets. According to the Georgia Tech Alumni Association:[156]

[the status of "alumni"] is open to all graduates of Georgia Tech, all former students of Georgia Tech who regularly matriculated and left Georgia Tech in good standing, active and retired members of the faculty and administration staff, and those who have rendered some special and conspicuous service to Georgia Tech or to [the alumni association].

The first class of 95 students entered Georgia Tech in 1888,[157] and the first two graduates received their degrees in 1890.[158] Since then, the institute has greatly expanded, with an enrollment of 12,069 undergraduates and 5,937 postgraduate students as of Spring 2009[update].[6]

Many distinguished individuals once called Georgia Tech home, the most notable being Jimmy Carter, former President of the United States and Nobel Peace Prize winner, who briefly attended Georgia Tech in the early 1940s prior to matriculating at and graduating from the United States Naval Academy.[159] Another Georgia Tech graduate and Nobel Prize winner, Kary Mullis, received the Nobel Prize in Chemistry in 1993.[160] A large number of businesspeople (CEOs, directors, etc.) began their careers at the College of Management.[161][162] Some of the most successful of these are Charles "Garry" Betty (CEO Earthlink),[163] David Dorman (CEO AT&T Corporation),[162] Mike Duke (CEO Wal-Mart),[164] and James D. Robinson III (CEO American Express and later director of The Coca-Cola Company).[165]

Tech graduates have been deeply influential in politics, military service, and activism. Atlanta mayor Ivan Allen, Jr. and former United States Senator Sam Nunn have both made significant changes from within their elected offices.[166][167] Former Georgia Tech president G. Wayne Clough was also a Tech graduate, the first Tech alumnus to serve in that position.[168] Many notable military commanders are alumni; William L. Ball was the 67th Secretary of the Navy,[169] John M. Brown III is the Commander of the United States Army Pacific Command,[170] and Leonard Wood was Chief of Staff of the Army and a Medal of Honor recipient for helping capture of the Apache chief Geronimo.[171] Wood was also Tech's first football coach and (simultaneously) the team captain, and was instrumental in Tech's first-ever football victory in a game against the University of Georgia.[171]

Numerous astronauts and NASA administrators spent time at Tech; most notably, Retired Vice Admiral Richard H. Truly was the eighth administrator of NASA, and later served as the president of the Georgia Tech Research Institute.[172] John Young was the first commander of the space shuttle and is the only person to have piloted four different classes of spacecraft.[173] Georgia Tech has its fair share of noteworthy engineers, scientists, and inventors. Kary Mullis developed the polymerase chain reaction,[160] Herbert Saffir developed the Saffir-Simpson Hurricane Scale,[174] and W. Jason Morgan made significant contributions to the theory of plate tectonics and geodynamics.[175] In computer science, Krishna Bharat developed Google News,[176] and D. Richard Hipp developed SQLite.[177] Architect Michael Arad designed the World Trade Center Memorial in New York City.[178]

Despite their highly technical backgrounds, Tech graduates are no strangers to the arts or athletic competition. Among them, comedian/actor Jeff Foxworthy of Blue Collar Comedy Tour fame and Randolph Scott both called Tech home.[179][180] Several famous athletes have, as well; about 150 Tech students have gone into the NFL,[181] with many others going into the NBA or MLB.[182][183] Well-known American football athletes include all-time greats such as Joe Hamilton,[184] Pat Swilling,[185] Billy Shaw,[181] and Joe Guyon,[181] former Tech head football coaches Pepper Rodgers and Bill Fulcher,[181][185] and recent students such as Calvin Johnson and Tashard Choice.[186][187] Some of Tech's recent entrants into the NBA include Javaris Crittenton,[188] Thaddeus Young,[189] Jarrett Jack,[190] and Luke Schenscher.[191] Award-winning baseball stars include Kevin Brown,[183] Mark Teixeira,[192] Nomar Garciaparra,[183] and Jason Varitek.[193] In golf, Tech alumni include the legendary Bobby Jones, who founded The Masters, and David Duval, who was ranked the No. 1 golfer in the world in 1999.[194]

References

- ^ a b c d e "A Walk Through Tech's History". Georgia Tech Alumni Magazine Online. Georgia Tech Alumni Association. Retrieved 2007-01-29.

- ^ "Between 2005 and 2006 Endowment Assets" (PDF). National Association of College and University Business Officers. Retrieved 2007-05-04.

- ^ Fain, Paul (2009-02-09). "Georgia Tech Taps Colorado-Boulder Chancellor as President". Chronicle of Higher Education. Retrieved 2009-02-09.

- ^ a b "Peterson Named President of Georgia Institute of Technology" (Press release). Georgia Institute of Technology. 2009-02-25. Retrieved 2009-02-25.

- ^ a b "Administration and Faculty: Faculty Profile". Georgia Tech Office of Institutional Research and Planning. Retrieved 2009-07-18.

- ^ a b c d e "Facts and Figures: Enrollment by College". Georgia Tech Office of Institutional Research & Planning. Retrieved 2009-07-18.

- ^ a b c d "The Hopkins Administration, 1888-1895". "A Thousand Wheels are set in Motion": The Building of Georgia Tech at the Turn of the 20th Century, 1888-1908. Georgia Institute of Technology. Retrieved 2006-12-30.

- ^ a b "The George W. Woodruff School of Mechanical Engineering" (PDF). The American Society of Mechanical Engineers. Retrieved 2007-04-22.

- ^ a b Brittain, James E. (1977). "Engineers and the New South Creed: The Formation and Early Development of Georgia Tech". Technology and Culture. 18 (2). Johns Hopkins University Press: 175–201. doi:10.2307/3103955.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help); Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ Lenz, Richard J. (2002). "Surrender Marker, Fort Hood, Change of Command Marker". The Civil War in Georgia, An Illustrated Travelers Guide. Sherpa Guides. Retrieved 2006-12-30.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ Selman, Sean (2002-03-27). "Presidential Tour of Campus Not the First for the Institute". A Presidential Visit to Georgia Tech. Georgia Institute of Technology. Archived from the original on 2008-02-02. Retrieved 2006-12-30.

- ^ "One Hundred Years Ago Was Eventful Year at Tech". BuzzWords. Georgia Tech Alumni Association. 2005-10-01. Retrieved 2006-12-30.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i "Tech Timeline". Georgia Tech Alumni Association. Retrieved 2007-03-27.

- ^ a b c "Underground Degrees". Tech Topics. Georgia Tech Alumni Association. Fall 1997. Retrieved 2007-03-15.

- ^ "History of Georgia State University". Georgia State University Library. 2003-10-06. Retrieved 2007-03-15.

- ^ McMath, Robert C. (1985). Engineering the New South: Georgia Tech 1885-1985. Athens, GA: University of Georgia Press. ISBN 08-2030-784-X.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ Combes, Richard (1992). "Origins of Industrial Extension: A Historical Case Study" (PDF). School of Public Policy, Georgia Institute of Technology. Retrieved 2007-05-28.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - ^ "History & Traditions". Georgia Institute of Technology. Retrieved 2009-07-29.

- ^ a b Terraso, David (2003-03-21). "Georgia Tech Celebrates 50 Years of Women". Georgia Institute of Technology News Room. Retrieved 2006-11-13.

- ^ "Facts and Figures: Enrollment by Gender". Georgia Tech Office of Institutional Research & Planning. Retrieved 2009-07-18.

- ^ a b c Edwards, Pat (1999-09-10). "Being new to Tech was not always so easy". The Technique. Retrieved 2007-04-10.

- ^ "Georgia Tech is Nation's No. 1 Producer of African-American Engineers in the Nation" (Press release). Georgia Institute of Technology. 2001-09-13. Retrieved 2006-11-13.

- ^ a b Susan Simmons (2000). "Analysis of the 1996 Summer Games on Real Estate Markets in Atlanta" (PDF). MIT Center for Real Estate. Retrieved 2009-07-29.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - ^ a b "Touring the Olympic Village". Tech Topics. Georgia Tech Alumni Association. Fall 1995. Retrieved 2007-05-21.

- ^ a b c d "You certainly won't find these in Webster's..." The Technique. 2004-08-20. Retrieved 2007-05-20. Cite error: The named reference "webster2004" was defined multiple times with different content (see the help page).

- ^ Joshi, Nikhil (2006-03-10). "Geibelhaus lectures on controversial president". The Technique. Retrieved 2007-01-29.

- ^ Gray, J.R. (1998-02-06). "Get over headtrip, Management". The Technique. Retrieved 2007-05-20.

- ^ Joshi, Nikhil (2005-03-04). "International plan takes root". The Technique. Retrieved 2007-03-16.

- ^ Chen, Inn Inn (2005-09-23). "Research, International Plan Fair hits Skiles Walkway". The Technique. Retrieved 2007-03-16.

- ^ Pogrebin, Robin (2008-03-16). "Georgia Tech President to lead Smithsonian". The New York Times. Retrieved 2008-04-28.

- ^ "Gary Schuster named Georgia Tech Interim President". Georgia Tech News Release. 2008-04-08. Retrieved 2008-04-28.

- ^ a b "Facts and Figures". Georgia Institute of Technology. Retrieved 2009-07-29.

- ^ "Women in Engineering at Georgia Tech". Georgia Tech College of Engineering. Retrieved 2007-10-09.

- ^ "Welcome!". Georgia Tech Society of Women Engineers. Retrieved 2009-07-29.

- ^ a b "Facts and Figures: Enrollment by Gender". Georgia Tech Office of Institutional Research & Planning. Retrieved 2009-07-29.

- ^ A slightly higher percentage of freshmen women attend during Summer. See Office of Institutional Research & Planning: Facts and Figures: Enrollment by Gender for verification.

- ^ "Financial Information: Revenue". Georgia Tech Fact Book. Georgia Institute of Technology. Retrieved 2007-09-17.

- ^ a b "Tech Receives Highest U.S. News Ranking Ever" (Press release). Georgia Institute of Technology. 2007-08-17. Retrieved 2009-06-18.

- ^ "Financial Information: Expenditures". Georgia Tech Fact Book. Georgia Institute of Technology. Retrieved 2009-07-18.

- ^ a b c d "Georgia Tech ranked seventh nationally among public universities for undergraduates" (Press release). Georgia Institute of Technology. 2008-08-21. Retrieved 2008-09-11.

- ^ "Engineering Graduate Program Rankings". U.S. News & World Report. Archived from the original on 2007-09-21. Retrieved 2007-12-24.

- ^ "THES - QS World University Rankings 2008 - Technology". QS Quacquarelli Symonds Ltd. Retrieved 2008-01-18.

- ^ "Times Higher Education - QS World University Rankings 2007 - Top 100 Universities". QS Network. Retrieved 2009-07-29.

- ^ "2006 General Catalog: Interdisciplinary Programs". Georgia Institute of Technology. Archived from the original on 2008-01-27. Retrieved 2007-03-16.

- ^ "Annual Report". Ivan Allen College of Liberal Arts. Archived from the original on 2008-01-01. Retrieved 2007-03-16.

- ^ "Institutions: Georgia Institute of Technology". Carnegie Classifications. Carnegie Foundation for the Advancement of Teaching. Retrieved 2007-12-25.

- ^ a b c d "Research". Georgia Tech Fact Book. Georgia Institute of Technology. Retrieved 2007-08-11.

- ^ a b c "2006 GTRI Annual Report" (PDF). Georgia Tech Research Institute. Retrieved 2007-04-03.

- ^ DeVol, Ross (2006-09-20). "Mind to Market: A Global Analysis of University Biotechnology Transfer and Commercialization". Milken Institute.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ "Nanotechnology Research Center Building". Georgia Tech Capital Projects. Archived from the original on 2008-01-29. Retrieved 2007-03-06.

- ^ "President's Undergraduate Research Awards (PURA)". Georgia Institute of Technology. Retrieved 2008-02-03.

- ^ "Research Option". Georgia Institute of Technology. Retrieved 2008-02-03.

- ^ Kent, Julie (2007-11-30). "Tech's first research journal begins submission process". The Technique. Retrieved 2008-01-02.

{{cite news}}: CS1 maint: date and year (link) - ^ "Cooperative Education named to national Hall of Honor". The Whistle. 2007-06-18. Retrieved 2007-09-24.

- ^ a b "Division of Professional Practice". Georgia Institute of Technology. Retrieved 2007-09-24.

- ^ "Graduate Cooperative Education Program". Division of Professional Practice. Georgia Institute of Technology. Retrieved 2007-09-24.

- ^ "Academic Information: Undergraduate Cooperative Program". 2006 Fact Book. Georgia Tech Office of Institutional Research and Planning. Retrieved 2007-09-24.

- ^ "UC Inducts 2007 Honorees into Co-op Hall of Honor". Division of Professional Practice. University of Cincinnati. 2007. Retrieved 2007-09-24.

- ^ Mabry, C. Jason (2003-08-22). "Bored yet? Find out what Tech and Atlanta have to offer". The Technique. Retrieved 2007-09-12.

- ^ "Hotels and Restaurants Nearby Georgia Tech". Georgia Tech Research Institute. Archived from the original on 2008-02-06. Retrieved 2008-02-09.

- ^ "Tech Square Retail". Georgia Tech Student Center. Retrieved 2008-02-09.

- ^ Ebrahimi, Aghigh (1999-09-10). "Home Park provides close alternative". The Technique. Retrieved 2007-04-10.

- ^ Meka, Hemanth Rao (1998-02-27). "Home Park Festival seeks to entertain neighbors, help kids". The Technique. Retrieved 2007-05-20.

- ^ "Student Organizations". GT Catalog 2007-2008. Georgia Institute of Technology. Retrieved 2008-02-09.

Georgia Tech has more than 350 chartered student organizations that offer a variety of activities for student involvement.

- ^ "Georgia Tech Student Government Association". Georgia Institute of Technology. Retrieved 2008-02-09.

- ^ Edwards, Pat (1997-04-18). "Ramblins". The Technique. Georgia Institute of Technology. Retrieved 2007-12-21.

- ^ "Greek Life". America's Best Colleges 2008. U.S. News & World Report. 2008. Archived from the original on 2008-02-13. Retrieved 2008-02-09.

{{cite web}}: Italic or bold markup not allowed in:|publisher=(help) - ^ "Princeton Review says Georgia Tech is One of the Toughest". BuzzWords. Georgia Tech Alumni Association. 2002-01-01. Retrieved 2008-02-09.

It's not news to students or graduates, but the Princeton Review confirms that Georgia Tech is one of the nation's toughest schools.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: date and year (link) - ^ Robert Franek ... (2003). The Best Southeastern Colleges: 100 Great Schools to Consider. The Princeton Review. ISBN 0375763295.

Because of the heavy workload at Georgia Tech, most students are 'overly stressed, worried about tomorrow's test, and driven by the desire for the degree. This student has only minimal time for social functions.'

- ^ Haynes, Derek (2002-08-30). "Princeton Review ranks Tech unhappy" (PDF). The Technique. Retrieved 2009-07-30.

- ^ Gordon, Jonathan (2003). "Just the Facts: Negative Publicity Perception at Georgia Tech" (PDF). Georgia Tech Office of Assessment. Retrieved 2008-02-09.

- ^ Kantor, Arcadiy (2008-05-23). "Absence of failure may be the key to real happiness". The Technique. Georgia Institute of Technology. Retrieved 2008-06-09.

The famous comment about the Tech lifestyle is that you can only choose any two pursuits among sleeping, studying and a social life.

- ^ a b c "Dedication of Renovated Brittain Dining Hall Notes". Georgia Tech Library. 2001-10-19. Retrieved 2009-07-18.

- ^ "Georgia Tech - Campus Dining". College Prowler. Retrieved 2009-07-18.

- ^ "FASET Orientation". Georgia Institute of Technology. Retrieved 2008-02-09.

- ^ "Georgia Tech Freshman Experience". Georgia Institute of Technology. Retrieved 2007-03-21.

- ^ "Annual First-Time Freshmen Retention Study" (PDF). Georgia Tech Office of Institutional Research and Planning. Fall 2006. Retrieved 2007-09-11.

- ^ "Student Related Information: Housing". Georgia Tech Fact Book. Georgia Tech Institute Research and Planning. Retrieved 2008-06-04.

- ^ Stephenson, James (2006-08-25). "Housing moves 150 dorm rooms to triples". The Technique. Retrieved 2007-06-10.

- ^ "Our Views Consensus Opinion: Three is a crowd". The Technique. 2006-08-25. Retrieved 2007-06-10.

- ^ Venkataraman, Ranganath (2007-11-17). "Students continue to live in triple dorms". The Technique. Retrieved 2007-06-10.

- ^ "Our Views Consensus Opinion". The Technique. 2007-03-09. Retrieved 2007-06-10.

- ^ a b Tabita, Craig (2007-03-09). "Tech acquires Ga. State dorms". The Technique. Georgia Institute of Technology. Retrieved 2008-06-14.

- ^ Pon, Corbin (2008-09-26). "First phase of North Avenue repair ends today". The Technique. Georgia Institute of Technology. Retrieved 2008-11-14.

- ^ "I-House Provides a Forum to Discuss the U.S. Political Future". Resident Housing Association. Georgia Institute of Technology. 2008-11-01. Retrieved 2008-11-14.

- ^ "Replica Tech Tower 'T' stolen from Student Services Building". The Technique. October 7, 2005. Retrieved 2006-12-19.

{{cite news}}: Unknown parameter|firstname=ignored (help); Unknown parameter|lastname=ignored (help) - ^ "Freshman Survival: You certainly won't find these in Webster's..." The Technique. 2002-08-23. Retrieved 2007-02-01.

- ^ Cheatham, Mike. "School Colors, Stolen Girl Friends, and Yellow Jacket Treachery". University of Georgia. Archived from the original on 2006-06-14. Retrieved 2009-07-30.

- ^ German, Brandon. "Official school colors". College Football Tradition. 1122productions.com. Retrieved 2007-03-16.

- ^ "Georgia Tech traditions". RamblinWreck.com. Georgia Tech Athletic Association. Retrieved 2007-03-12.

- ^ "About the Glee Club". Georgia Tech Glee Club. Retrieved 2007-11-08.

- ^ a b c Johnson, Rusty (2000-02-25). "Campus music programs have storied history". The Technique. Retrieved 2007-03-17.

- ^ "Century of Singing". Tech Topics. Georgia Tech Alumni Association. Spring 2006. Retrieved 2007-06-07.

- ^ "Ancient History". Georgia Tech Glee Club. Retrieved 2009-07-18.

- ^ "Georgia Tech Athletic Bands". Georgia Tech College of Architecture. Retrieved 2007-10-09.

- ^ "Orchestra". Georgia Tech Music Department. Retrieved 2009-07-18.

- ^ "Nothin' but Treble". Nothin' but Treble. Retrieved 2009-07-29.

- ^ "News". Sympathetic Vibrations. Retrieved 2009-07-29.

- ^ "News". Infinite Harmony. Retrieved 2009-07-29.

- ^ "About Us". Ferst Center for the Arts. Retrieved 2007-08-23.

- ^ Guyton, Andrew (2007-03-30). "Third annual MomoCon draws 2,600 gaming fans". The Technique. Retrieved 2007-04-03.

- ^ Stephenson, James (2006-11-17). "PBA inquires about managing WREK". The Technique. Retrieved 2009-07-18.

- ^ Stephenson, James (2007-04-06). "PBA meets with WREK". The Technique. Retrieved 2009-07-18.

- ^ Tabita, Craig (2007-02-16). "RCB meets with GPB representative". The Technique. Retrieved 2009-07-18.

- ^ a b "Georgia Tech Blueprint Yearbook". Blueprint. Retrieved 2009-07-18.

- ^ "North Avenue Review". North Avenue Review. Archived from the original on 2008-01-12. Retrieved 2009-07-29.

{{cite web}}:|archive-date=/|archive-url=timestamp mismatch; 2008-01-21 suggested (help) - ^ "North Avenue Review". Georgia Tech Library and Information Center. Retrieved 2009-07-29.

- ^ "Erato". Erato. Retrieved 2009-07-30.

- ^ "FAQs". The Technique. Retrieved 2009-07-18.

- ^ a b "Student Related Information: Student Organizations". Georgia Tech Fact Book. Georgia Institute of Technology. Retrieved 2009-07-18.

- ^ "Remarks by President Wayne Clough" (PDF). 2002-11-02.

Only 21 percent of Tech undergrads are active Greeks, but Greeks or Greek events accounted for more than half of the 14 students hospitalized last year for alcohol poisoning, and for more than half of the seven cases we have had so far this year.

- ^ "Channel Lineup". Georgia Tech Cable Network. Retrieved 2007-05-20.

- ^ "OIT Home Page". Georgia Tech Office of Information Technology. Retrieved 2007-03-16.

- ^ "ResNet". Georgia Tech ResNet. Retrieved 2007-03-16.

- ^ "Patrol Division". Georgia Tech Police Department. Retrieved 2008-02-09.

- ^ a b "Crime Statistics". Georgia Tech Police Department. Retrieved 2008-02-09.

- ^ "Atlanta, Used to Praise, Confronts Crime Ranking". New York Times. Retrieved 2008-10-11.

- ^ "Atlanta's violent crime at lowest level since '69". The Atlanta Journal-Constitution. 2006-09-27. Retrieved 2006-09-29.

- ^ Nichols, Tempress (2007-08-16). "Atlanta Pleased With Crime Ranking, Macon Has Doubts, Augusta Not Reported". WAGT. nbcagusta.com. Retrieved 2008-10-11.

- ^ a b c d "Georgia Tech Reconnects, Renews Section of Atlanta Business District with Technology Square" (Press release). Georgia Institute of Technology. 2003-10-20. Retrieved 2009-07-31.

- ^ a b c d e "Campus Map". Georgia Tech Alumni Association. Retrieved 2007-10-18.

- ^ "Tech Virtual Tour". Georgia Institute of Technology. Retrieved 2007-10-18.

- ^ Morgan, Jenny (2008-08-22). "Sticker shock? Get textbook deals for any budget". The Technique. Retrieved 2009-08-03.

- ^ "About the School". Georgia Tech School of Modern Languages. Retrieved 2009-07-27.

- ^ "Swann Dormitory (1901)". A Thousand Wheels are set in Motion. Georgia Tech Library and Information Center. Retrieved 2009-07-27.

- ^ Kumar, Neeraj (2000-09-22). "New construction on the Hill recreates historic appearance near Tech Tower". The Technique. Retrieved 2007-03-16.

- ^ "Georgia Institute of Technology Historic District". National Park Service Atlanta. Retrieved 2007-05-26.

- ^ "Tech Rec". Fun On Every Floor. Georgia Institute of Technology. Retrieved 2007-08-23.

- ^ "Campus Master Plan". Georgia Tech Capital Planning & Space Management. 2004. Retrieved 2007-08-22.

- ^ Goodrich, Kaitlin (2008-07-11). "Clough building plans finalized for construction". The Technique. Retrieved 2009-07-28.

- ^ "Technology Square". Georgia Tech Office of Development. Archived from the original on 2008-02-13. Retrieved 2008-02-09.

- ^ Stephenson, James (2007-01-19). "Renovated Fifth Street Bridge opens". The Technique. Retrieved 2007-03-25.

- ^ Subramanian, Arjun (2003-06-13). "Management prepares for Tech Square move". The Technique. Archived from the original on 2007-09-29. Retrieved 2009-08-03.

- ^ a b TVS (2006-01-01). "Georgia Tech's Technology Square". RevitalizationOnline. Retrieved 2008-02-09.

- ^ "Technology Square - Georgia Institute of Technology". TVS. Retrieved 2009-07-30.

- ^ "Georgia Tech, SEDA to Break Ground For New GTREP Campus in Savannah" (Press release). Georgia Institute of Technology. 2002-06-10. Retrieved 2007-08-12.

{{cite press release}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - ^ "Georgia Tech Opens Campus in Savannah" (Press release). Georgia Institute of Technology. 2003-10-14. Retrieved 2007-08-12.

{{cite press release}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - ^ a b Dykes, Jennifer (1999-10-15). "Clough addresses Institute". The Technique. Retrieved 2007-05-22.

- ^ "About Georgia Tech Lorraine". Georgia Tech Lorraine. Retrieved 2007-01-29.

- ^ "Georgia Tech Is Sued For Non-French Web Site". New York Times. 1996-12-31. Retrieved 2008-02-24.

- ^ "Campuses & Global Reach". Georgia Institute of Technology. Retrieved 2009-07-29.

- ^ "Paris Program". Georgia Tech College of Architecture. Retrieved 2009-07-27.

- ^ "A Look Back / A Look Forward". Georgia Tech College of Engineering. August 2007. Retrieved 2008-06-02.

- ^ "Georgia Tech plans SEZ". The Times of India. 2008-01-13. Retrieved 2008-06-02.

- ^ "Georgia Tech to set up campus in Hyderabad". Indo-Asian News Service. Pragati Infosoft. 2007-06-06. Retrieved 2008-06-02.

- ^ Hoover, Kent (2007-08-05). "U.S. universities expand overseas efforts to keep global edge". MSNBC. Archived from the original on 2007-08-07. Retrieved 2007-08-09.

- ^ Cromartie, Bill (2002) [1977]. Clean Old-fashioned Hate: Georgia Vs. Georgia Tech. Strode Publishers. ISBN 09-3252-064-2.

- ^ "Georgia Tech Wins NCAA Women's Tennis Title". RamblinWreck.com. Georgia Tech Athletic Association. 2007-05-22. Retrieved 2007-05-23.

- ^ "Georgia Tech captures first NCAA women's tennis title". ESPNU. ESPN.com. 2007-05-23. Retrieved 2007-05-23.

- ^ a b c d e Edwards, Pat (2000-08-25). "Fight Songs". The Technique. Retrieved 2007-04-10. Cite error: The named reference "songs" was defined multiple times with different content (see the help page).

- ^ "Georgia Tech Traditions". Georgia Tech Athletic Association. Retrieved 2007-02-12.

- ^ "Who's No. 1? Fighting Words About Battle Hymns". Tech Topics. Georgia Tech Alumni Association. Summer 1991. Retrieved 2007-05-20.

- ^ a b c "Inventory of the Georgia Tech Songs Collection, 1900-1953". Georgia Tech Archives and Records Management. Retrieved 2007-05-20.

- ^ "White and Gold". Ramblin' Memories: Traditions, Legends and Sounds of Georgia Tech. Georgia Tech Alumni Association. Retrieved 2008-02-03.

- ^ "Georgia Tech Aquatic Center". RamblinWreck.com. Georgia Tech Athletic Association. Retrieved 2007-05-25.

- ^ "Bylaws of the Georgia Tech Alumni Association, Inc" (PDF). Georgia Tech Alumni Association. Retrieved 2007-05-03.

- ^ "GT Buildings: GTVA-UKL999-A". A Thousand Wheels are set in Motion: The Building of Georgia Tech at the Turn of the 20th Century, 1888-1908. Georgia Tech Library. Retrieved 2007-01-29.

- ^ "20 Common Questions about Georgia Tech". Georgia Tech Archives and Records Management. Retrieved 2007-03-13.

- ^ "History of the NROTC Unit at Georgia Institute of Technology". Georgia Tech NROTC. Retrieved 2007-03-05.

- ^ a b Goettling, Gary (Summer 1994). "The Unconventional Genius of Dr. Kary Banks Mullis". Georgia Tech Alumni Magazine Online. Georgia Tech Alumni Association. Retrieved 2007-03-06.

- ^ "College of Management MBA Program 2005" (PDF). Georgia Tech College of Management. Retrieved 2007-03-24.

- ^ a b "College of Management Honors Exceptional Alumni" (Press release). Georgia Institute of Technology. 2006-05-01. Retrieved 2007-03-06.

- ^ "EarthLink's Leadership: Charles (Gary) Betty". EarthLink. Archived from the original on 2007-12-18. Retrieved 2009-08-01.

- ^ "Michael T. Duke". Wal-Mart Stores. Retrieved 2009-08-01.

- ^ Schwartz, Jerry (Summer 1993). "On His Own". Georgia Tech Alumni Magazine Online. Georgia Tech Alumni Association. Retrieved 2009-08-01.

- ^ "Ivan Allen Jr. Timeline". Ivan Allen College of Liberal Arts. Retrieved 2007-03-06.

- ^ "A Conversation With Sam Nunn". Georgia Tech Alumni Magazine Online. Georgia Tech Alumni Association. Spring 1990. Retrieved 2007-03-06.

- ^ "Presidents of Georgia Tech". Georgia Tech Office of Institutional Research and Planning. Retrieved 2007-03-06.

- ^ "Appointment of William L. Ball III as Assistant to the President for Legislative Affairs". Public Papers of Ronald Reagan. Ronald Reagan Presidential Library. 1986-02-07. Retrieved 2007-03-07.

- ^ "Lieutenant General John M. Brown III". United States Army, Pacific. Archived from the original on 2007-10-06. Retrieved 2007-03-07.

- ^ a b Byrd, Joseph (Spring 1992). "From Civil War Battlefields to the Moon: Leonard Wood". Tech Topics. Georgia Tech Alumni Association. Retrieved 2007-03-12.

- ^ "Astronaut Bio:Richard H. Truly". National Aeronautics and Space Administration. 1992-03. Retrieved 2007-03-07.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - ^ "Astronaut Bio: John Young". National Aeronautics and Space Administration. 2005-05. Retrieved 2007-03-07.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - ^ "Engineering Hall of Fame: College inducts alumni who have made "significant impact on the world"". Tech Topics. Georgia Tech Alumni Association. Winter 1995. Retrieved 2007-03-07.

- ^ "Biography of Vetlesen Prize Winner". Trustees of Columbia University. Retrieved 2007-03-07.

- ^ "Alumni Spotlight: Krishna Bharat". Georgia Tech College of Computing. Archived from the original on 2006-09-11. Retrieved 2009-08-01.

{{cite web}}:|archive-date=/|archive-url=timestamp mismatch; 2006-09-01 suggested (help) - ^ "Speaker D. Richard Hipp". O'Reilly Open Source Convention. Retrieved 2007-03-09.

- ^ "Profiles: Michael Arad". Georgia Institute of Technology. Archived from the original on 2007-06-11. Retrieved 2007-03-09.

- ^ Goettling, Gary (Fall 1992). "Redneck Repartee". Tech Topics. Georgia Tech Alumni Association. Retrieved 2007-03-10.

- ^ Cathey, Boyd D. "Randolph Scott (1898-1987)". North Carolina History Project. Retrieved 2007-03-05.

- ^ a b c d "National Football League players who Attended Georgia Tech". databaseFootball.com. Retrieved 2007-03-13.

- ^ "NBA players who Attended Georgia Institute of Technology". databaseBasketball.com. Retrieved 2007-03-18.

- ^ a b c "Players who Played for Georgia Institute of Technology". baseball-reference.com. Retrieved 2007-03-14.

- ^ "Player Bio: Joe Hamilton". RamblinWreck.com. Georgia Tech Athletic Association. Retrieved 2007-03-08.

- ^ a b "Georgia Tech Honors" (PDF). Georgia Tech Athletic Association. 2007. Retrieved 2007-09-30.

- ^ "Player Bio: Calvin Johnson". RamblinWreck.com. Georgia Tech Athletic Association. Retrieved 2007-03-08.

- ^ "Player Bio: Tashard Choice". RamblinWreck.com. Georgia Tech Athletic Association. Retrieved 2007-04-09.

- ^ "Player Bio: Javaris Crittenton". RamblinWreck.com. Georgia Tech Athletic Association. Retrieved 2007-03-13.

- ^ "Player Bio: Thaddeus Young". RamblinWreck.com. Georgia Tech Athletic Association. Retrieved 2007-03-13.

- ^ "Jarrett Jack Info Page". NBA.com. Retrieved 2007-03-10.

- ^ "Player Bio: Luke Schenscher". RamblinWreck.com. Georgia Tech Athletic Association. Retrieved 2007-03-10.

- ^ "Rapid Success". Tech Topics. Georgia Tech Alumni Association. Fall 2005. Retrieved 2007-03-05.

- ^ "Alumni In The Majors". beesball.com. Retrieved 2007-03-14.

- ^ "Georgia Tech Athletics Hall of Fame". RamblinWreck.com. Georgia Tech Athletic Association. Retrieved 2007-03-04.

Further reading

- Brittain, Marion L. (1948). The Story of Georgia Tech. Chapel Hill, NC: University of North Carolina Press.

- Cromartie, Bill (2002) [1977]. Clean Old-fashioned Hate: Georgia Vs. Georgia Tech. Strode Publishers. ISBN 09-3252-064-2.

- McMath, Robert C. (1985). Engineering the New South: Georgia Tech 1885-1985. Athens, GA: University of Georgia Press. ISBN 08-2030-784-X.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - Wallace, Robert (1969). Dress Her in WHITE and GOLD: A biography of Georgia Tech. The Georgia Tech Foundation, Inc.

External links

- Educational institutions established in 1885

- Georgia Institute of Technology

- Oak Ridge Associated Universities

- Association of Public and Land-Grant Universities

- Southern Association of Colleges and Schools

- Technical universities and colleges

- Universities and colleges in Georgia (U.S. state)

- Glass science institutes

- Engineering universities and colleges in the United States

- Schools in Atlanta, Georgia