Gone with the Wind (film)

| Gone with the Wind | |

|---|---|

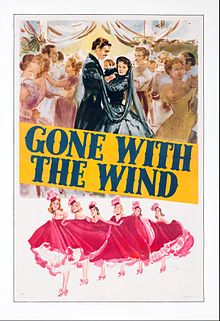

Theatrical pre-release poster | |

| Directed by | Victor Fleming |

| Screenplay by | Sidney Howard |

| Produced by | David O. Selznick |

| Starring | |

| Cinematography | Ernest Haller |

| Edited by | |

| Music by | Max Steiner |

Production companies | |

| Distributed by | Loew's Inc.[nb 1] |

Release date |

|

Running time |

|

| Country | United States |

| Language | English |

| Budget | $3.85 million |

| Box office | >$390 million |

Gone with the Wind is a 1939 American epic-historical romance film adapted from Margaret Mitchell's 1936 novel Gone with the Wind. It was produced by David O. Selznick of Selznick International Pictures and directed by Victor Fleming. Set in the 19th-century American South, the film tells the story of Scarlett O'Hara, the strong-willed daughter of a Georgia plantation owner, from her romantic pursuit of Ashley Wilkes, who is married to his cousin, Melanie Hamilton, to her marriage to Rhett Butler. Set against the backdrop of the American Civil War and Reconstruction era, the story is told from the perspective of wealthy white Southerners. The leading roles are portrayed by Vivien Leigh (Scarlett), Clark Gable (Rhett), Leslie Howard (Ashley), and Olivia de Havilland (Melanie).

The production of the film was difficult from the start. Filming was delayed for two years due to Selznick's determination to secure Gable for the role of Rhett Butler, and the "search for Scarlett" led to 1,400 women being interviewed for the part. The original screenplay was written by Sidney Howard, but underwent many revisions by several writers in an attempt to get it down to a suitable length. The original director, George Cukor, was fired shortly after filming had begun and was replaced by Fleming, who in turn was briefly replaced by Sam Wood while Fleming took some time off due to exhaustion.

The film received positive reviews upon its release in December 1939, although some reviewers found it dramatically lacking and bloated. The casting was widely praised and many reviewers found Leigh especially suited to her role as Scarlett. At the 12th Academy Awards, it received ten Academy Awards (eight competitive, two honorary) from thirteen nominations, including wins for Best Picture, Best Director (Fleming), Best Adapted Screenplay (posthumously awarded to Sidney Howard), Best Actress (Leigh) and Best Supporting Actress (Hattie McDaniel, becoming the first African-American to win an Academy Award). It set records for the total number of wins and nominations at the time. The film was immensely popular, becoming the highest-earning film made up to that point, and retained the record for over a quarter of a century. When adjusted for monetary inflation, it is still the most successful film in box-office history.

The film has been criticized as historical revisionism glorifying slavery, but nevertheless, it has been credited for triggering changes to the way African-Americans are depicted on film. It was re-released periodically throughout the 20th century and became ingrained in popular culture. The film is regarded as one of the greatest films of all time; it has placed in the top ten of the American Film Institute's list of top 100 American films since the list's inception in 1998, and in 1989, the United States Library of Congress selected it for preservation in the National Film Registry.

Plot

- Part 1

On the eve of the American Civil War in 1861, Scarlett O'Hara lives at Tara, her family's cotton plantation in Georgia, with her parents and two sisters. Scarlett learns that Ashley Wilkes—whom she secretly loves—is to be married to his cousin, Melanie Hamilton, and the engagement is to be announced the next day at a barbecue at Ashley's home, the nearby plantation Twelve Oaks.

At the Twelve Oaks party, Scarlett secretly declares her feelings to Ashley, but he rebuffs her by responding that he and Melanie are more compatible. Scarlett is incensed when she discovers another guest, Rhett Butler, has overheard their conversation; a smitten Rhett promises Scarlett he will keep her secret. The barbecue is disrupted by the declaration of war and the men rush to enlist. As Scarlett watches Ashley kiss Melanie goodbye, Melanie's younger brother Charles proposes to her. Although she does not love him, Scarlett consents and they are married before he leaves to fight.

Scarlett is widowed when Charles dies from a bout of pneumonia and measles while serving in the Confederate Army. Scarlett's mother sends her to the Hamilton home in Atlanta to cheer her up, although the O'Haras' outspoken housemaid Mammy tells Scarlett she knows she is going there only to wait for Ashley's return. Scarlett, who should not attend a party while in mourning, attends a charity bazaar in Atlanta with Melanie where she runs into Rhett again, now a blockade runner for the Confederacy. Celebrating a Confederate victory and to raise money for the Confederate war effort, gentlemen are invited to bid for ladies to dance with them. Rhett makes an inordinately large bid for Scarlett and, to the disapproval of the guests, she agrees to dance with him.

The tide of war turns against the Confederacy after the Battle of Gettysburg in which many of the men of Scarlett's town are killed. Scarlett makes another unsuccessful appeal to Ashley while he is visiting on Christmas furlough, although they do share a private and passionate kiss in the parlor on Christmas Day, just before he returns to war.

Eight months later, as the city is besieged by the Union Army in the Atlanta Campaign, Scarlett and her young house servant Prissy must deliver Melanie's baby without medical assistance after she goes into premature labor. Afterwards, Scarlett calls upon Rhett to take her home to Tara with Melanie, her baby, and Prissy; he collects them in a horse and wagon, but once out of the city chooses to go off to fight, leaving Scarlett and the group to make their own way back to Tara. Upon her return home, Scarlett finds Tara deserted, except for her parents, her sisters, and two servants: Mammy and Pork. Scarlett learns that her mother has just died of typhoid fever and her father has become incompetent. With Tara pillaged by Union troops and the fields untended, Scarlett vows she will do anything for the survival of her family and herself.

- Part 2

As the O'Haras and their servants work in the cotton fields, Scarlett's father is killed after he is thrown from his horse in an attempt to chase away a scalawag from his land. With the defeat of the Confederacy Ashley also returns, but finds he is of little help at Tara. When Scarlett begs him to run away with her, he confesses his desire for her and kisses her passionately, but says he cannot leave Melanie. Unable to pay the taxes on Tara implemented by Reconstructionists, Scarlett dupes her younger sister Suellen's fiancé, the middle-aged and wealthy mill owner Frank Kennedy, into marrying her, by saying Suellen got tired of waiting and married another beau.

Frank, Ashley, Rhett and several other accomplices make a night raid on a shanty town after Scarlett is attacked while driving through it alone, resulting in Frank's death. With Frank's funeral barely over, Rhett proposes to Scarlett and she accepts. They have a daughter whom Rhett names Bonnie Blue, but Scarlett, still pining for Ashley and chagrined at the perceived ruin of her figure, lets Rhett know that she wants no more children and that they will no longer share a bed.

One day at Frank's mill, Scarlett and Ashley are seen embracing by Ashley's sister, India, and harboring an intense dislike of Scarlett she eagerly spreads rumors. Later that evening, Rhett, having heard the rumors, forces Scarlett to attend a birthday party for Ashley; incapable of believing anything bad of her beloved sister-in-law, Melanie stands by Scarlett's side so that all know that she believes the gossip to be false. After returning home from the party, Scarlett finds Rhett downstairs drunk, and they argue about Ashley. Rhett kisses Scarlett against her will, stating his intent to have sex with her that night, and carries the struggling Scarlett to the bedroom. The next day, Rhett apologizes for his behavior and offers Scarlett a divorce, which she rejects, saying that it would be a disgrace. When Rhett returns from an extended trip to London Scarlett informs him that she is pregnant, but an argument ensues which results in her falling down a flight of stairs and suffering a miscarriage. As she is recovering, tragedy strikes when Bonnie dies while attempting to jump a fence with her pony.

Scarlett and Rhett visit Melanie on her deathbed, who has suffered complications arising from a new pregnancy. As Scarlett consoles Ashley, Rhett returns to Tara; realizing that Ashley only ever truly loved Melanie, Scarlett dashes after Rhett to find him preparing to leave for good. She pleads with him, telling him she realizes now that she has loved him all along and that she never really loved Ashley, but Rhett says that with Bonnie's death went any chance of reconciliation. Scarlett begs him to stay but Rhett rebuffs her and walks out the door and into the early morning fog, leaving her weeping on the staircase and vowing to one day win back his love.

Cast

Despite receiving top-billing in the opening credits, Gable—along with Leigh, Howard, and de Havilland who receive second, third and fourth billing respectively—has a relatively low placing in the cast list, due to its unusual structure. Rather than ordered by conventional billing, the cast is broken down into three sections: the Tara plantation, Twelve Oaks, and Atlanta. The cast's names are ordered according to the social rank of the characters; therefore Thomas Mitchell, who plays Gerald O'Hara, leads the cast list as the head of the O'Hara family, while Barbara O'Neil as his wife receives the second credit and Vivien Leigh as the eldest daughter the third credit, despite having the most screen time. Similarly, Howard C. Hickman as John Wilkes is credited over Leslie Howard who plays his son, and Clark Gable, who plays only a visitor at Twelve Oaks, receives a relatively low credit in the cast list, despite being presented as the "star" of the film in all the promotional literature.[2] Following the death of Mary Anderson—who played Maybelle Merriwether—in April 2014, there are only two surviving credited cast members from the film: Olivia de Havilland who played Melanie Wilkes and Mickey Kuhn, who played her son Beau Wilkes.[3]

- Tara plantation

- Thomas Mitchell as Gerald O'Hara

- Barbara O'Neil as Ellen O'Hara (his wife)

- Vivien Leigh as Scarlett O'Hara (daughter)

- Evelyn Keyes as Suellen O'Hara (daughter)

- Ann Rutherford as Carreen O'Hara (daughter)

- George Reeves as Brent Tarleton (actually as Stuart)[nb 2]

- Fred Crane as Stuart Tarleton (actually as Brent)[nb 2]

- Hattie McDaniel as Mammy (house servant)

- Oscar Polk as Pork (house servant)

- Butterfly McQueen as Prissy (house servant)

- Victor Jory as Jonas Wilkerson (field overseer)

- Everett Brown as Big Sam (field foreman)

- At Twelve Oaks

- Howard Hickman as John Wilkes

- Alicia Rhett as India Wilkes (his daughter)

- Leslie Howard as Ashley Wilkes (his son)

- Olivia de Havilland as Melanie Hamilton (their cousin)

- Rand Brooks as Charles Hamilton (Melanie's brother)

- Carroll Nye as Frank Kennedy (a guest)

- Clark Gable as Rhett Butler (a visitor from Charleston)

- In Atlanta

- Laura Hope Crews as Aunt Pittypat Hamilton

- Eddie Anderson as Uncle Peter (her coachman)

- Harry Davenport as Doctor Meade

- Leona Roberts as Mrs. Meade

- Jane Darwell as Mrs. Merriwether

- Ona Munson as Belle Watling

- Minor supporting roles

- Paul Hurst as the Yankee deserter

- Cammie King Conlon as Bonnie Blue Butler

- J. M. Kerrigan as Johnny Gallagher

- Jackie Moran as Phil Meade

- Lillian Kemble-Cooper as Bonnie's nurse in London

- Marcella Martin as Cathleen Calvert

- Mickey Kuhn as Beau Wilkes

- Irving Bacon as the Corporal

- William Bakewell as the mounted officer

- Isabel Jewell as Emmy Slattery

- Eric Linden as the amputation case

- Ward Bond as Tom, the Yankee captain

- Cliff Edwards as the reminiscent soldier

- Yakima Canutt as the renegade

- Louis Jean Heydt as the hungry soldier holding Beau Wilkes

- Olin Howland as the carpetbagger businessman

- Robert Elliott as the Yankee major

- Mary Anderson as Maybelle Merriwether

Production

Before publication of the novel, several Hollywood executives and studios declined to create a film based on it, including Louis B. Mayer and Irving Thalberg at Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer (MGM), Pandro Berman at RKO Pictures, and David O. Selznick of Selznick International Pictures. Jack L. Warner liked the story, but Warner Bros.'s biggest star Bette Davis was uninterested, and Darryl Zanuck of 20th Century-Fox did not offer enough money. Selznick changed his mind after his story editor Kay Brown and business partner John Hay Whitney urged him to buy the film rights. In July 1936—a month after it was published—Selznick bought the rights for $50,000.[4][5][6]

Casting

The casting of the two lead roles became a complex, two-year endeavor. For the role of Rhett Butler, Selznick wanted Clark Gable from the start, but Gable was under contract to MGM, who never loaned him to other studios.[4] Gary Cooper was considered, but Samuel Goldwyn—to whom Cooper was under contract—refused to loan him out.[7] Warner offered a package of Bette Davis, Errol Flynn, and Olivia de Havilland for lead roles in return for the distribution rights.[8] By this time, Selznick was determined to get Gable and eventually struck a deal with MGM. Selznick's father-in-law, MGM chief Louis B. Mayer, offered in August 1938 to provide Gable and $1,250,000 for half of the film's budget but for a high price: Selznick would have to pay Gable's weekly salary, and half the profits would go to MGM while Loew's, Inc—MGM's parent company—would release the film.[4][7]

The arrangement to release through MGM meant delaying the start of production until the end of 1938, when Selznick's distribution deal with United Artists concluded.[7] Selznick used the delay to continue to revise the script and, more importantly, build publicity for the film by searching for the role of Scarlett. Selznick began a nationwide casting call that interviewed 1,400 unknowns. The effort cost $100,000 and was useless for the film, but created "priceless" publicity.[4] Early frontrunners included Miriam Hopkins and Tallulah Bankhead, who were regarded as possibilities by Selznick prior to the purchase of the film rights; Joan Crawford, who was signed to MGM, was also considered as a potential pairing with Gable. After a deal was struck with MGM, Selznick held discussions with Norma Shearer—who was MGM's top female star at the time—but she withdrew herself from consideration. Katharine Hepburn lobbied hard for the role with the support of her friend, George Cukor, who had been hired to direct, but she was vetoed by Selznick who felt she was not right for the part.[7][8][9]

Many famous—or soon-to-be-famous—actresses were considered, but only thirty-one women were actually screen-tested for Scarlett including Ardis Ankerson, Jean Arthur, Tallulah Bankhead, Diana Barrymore, Joan Bennett, Nancy Coleman, Frances Dee, Ellen Drew (as Terry Ray), Paulette Goddard, Susan Hayward (under her real name of Edythe Marrenner), Vivien Leigh, Anita Louise, Haila Stoddard, Margaret Tallichet, Lana Turner and Linda Watkins.[10] Although Margaret Mitchell refused to publicly name her choice, the actress who came closest to winning her approval was Miriam Hopkins, who Mitchell felt was just the right type of actress to play Scarlett as written in the book. However, Hopkins was in her mid-thirties at the time and was considered too old for the part.[7][8][9] Four actresses, including Jean Arthur and Joan Bennett, were still under consideration by December 1938; however, only two finalists, Paulette Goddard and Vivien Leigh, were tested in Technicolor, both on December 20.[11] Goddard almost won the role, but controversy over her marriage with Charlie Chaplin caused Selznick to change his mind.[4]

Selznick had been quietly considering Vivien Leigh, a young English actress who was still little known in America, for the role of Scarlett since February 1938 when Selznick saw her in Fire Over England and A Yank at Oxford. Leigh's American agent was the London representative of the Myron Selznick talent agency (headed by David Selznick's brother, one of the owners of Selznick International), and she had requested in February that her name be submitted for consideration as Scarlett. By the summer of 1938 the Selznicks were negotiating with Alexander Korda, to whom Leigh was under contract, for her services later that year.[12] Selznick's brother arranged for them to meet for the first time on the night of December 10, 1938, when the burning of Atlanta was filmed. In a letter to his wife two days later, Selznick admitted that Leigh was "the Scarlett dark horse", and after a series of screen tests, her casting was announced on January 13, 1939.[13] Just before the shooting of the film, Selznick informed newspaper columnist Ed Sullivan: "Scarlett O'Hara's parents were French and Irish. Identically, Miss Leigh's parents are French and Irish."[14]

Screenplay

Of original screenplay writer Sidney Howard, film historian Joanne Yeck writes, "reducing the intricacies of Gone with the Wind's epic dimensions was a herculean task ... and Howard's first submission was far too long, and would have required at least six hours of film; ... [producer] Selznick wanted Howard to remain on the set to make revisions ... but Howard refused to leave New England [and] as a result, revisions were handled by a host of local writers".[15] Selznick dismissed director George Cukor three weeks into filming and sought out Victor Fleming, who was directing The Wizard of Oz at the time. Fleming was dissatisfied with the script, so Selznick brought in famed writer Ben Hecht to rewrite the entire screenplay within five days. Hecht returned to Howard's original draft and by the end of the week had succeeded in revising the entire first half of the script. Selznick undertook rewriting the second half himself but fell behind schedule, so Howard returned to work on the script for one week, reworking several key scenes in part two.[16]

"By the time of the film's release in 1939, there was some question as to who should receive screen credit," writes Yeck. "But despite the number of writers and changes, the final script was remarkably close to Howard's version. The fact that Howard's name alone appears on the credits may have been as much a gesture to his memory as to his writing, for in 1939 Sidney Howard died at age 48 in a farm-tractor accident, and before the movie's premiere."[15] Selznick, in a memo written in October 1939, discussed the film's writing credits: "[Y]ou can say frankly that of the comparatively small amount of material in the picture which is not from the book, most is my own personally, and the only original lines of dialog which are not my own are a few from Sidney Howard and a few from Ben Hecht and a couple more from John Van Druten. Offhand I doubt that there are ten original words of [Oliver] Garrett's in the whole script. As to construction, this is about eighty per cent my own, and the rest divided between Jo Swerling and Sidney Howard, with Hecht having contributed materially to the construction of one sequence."[17]

According to Hecht biographer, William MacAdams, "At dawn on Sunday, February 20, 1939, David Selznick ... and director Victor Fleming shook Hecht awake to inform him he was on loan from MGM and must come with them immediately and go to work on Gone with the Wind, which Selznick had begun shooting five weeks before. It was costing Selznick $50,000 each day the film was on hold waiting for a final screenplay rewrite and time was of the essence. Hecht was in the middle of working on the film At the Circus for the Marx Brothers. Recalling the episode in a letter to screenwriter friend Gene Fowler, he said he hadn't read the novel but Selznick and director Fleming could not wait for him to read it. They would act out scenes based on Sidney Howard's original script which needed to be rewritten in a hurry. Hecht wrote, "After each scene had been performed and discussed, I sat down at the typewriter and wrote it out. Selznick and Fleming, eager to continue with their acting, kept hurrying me. We worked in this fashion for seven days, putting in eighteen to twenty hours a day. Selznick refused to let us eat lunch, arguing that food would slow us up. He provided bananas and salted peanuts ... thus on the seventh day I had completed, unscathed, the first nine reels of the Civil War epic."

MacAdams writes, "It is impossible to determine exactly how much Hecht scripted ... In the official credits filed with the Screen Writers Guild, Sidney Howard was of course awarded the sole screen credit, but four other writers were appended ... Jo Swerling for contributing to the treatment, Oliver H. P. Garrett and Barbara Keon to screenplay construction, and Hecht, to dialogue ..."[18]

Filming

Principal photography began January 26, 1939, and ended on July 1, with post-production work continuing until November 11, 1939. Director George Cukor, with whom Selznick had a long working relationship, and who had spent almost two years in pre-production on Gone with the Wind, was replaced after less than three weeks of shooting.[8][nb 3] Selznick and Cukor had already disagreed over the pace of filming and the script,[8][19] but other explanations put Cukor's departure down to Gable's discomfort at working with him. Emanuel Levy, Cukor's biographer, claimed that Clark Gable had worked Hollywood's gay circuit as a hustler and that Cukor knew of his past, so Gable used his influence to have him discharged.[21] Vivien Leigh and Olivia de Havilland learned of Cukor's firing on the day the Atlanta bazaar scene was filmed, and the pair went to Selznick's office in full costume and implored him to change his mind. Victor Fleming, who was directing The Wizard of Oz, was called in from MGM to complete the picture, although Cukor continued privately to coach Leigh and De Havilland.[16] Another MGM director, Sam Wood, worked for two weeks in May when Fleming temporarily left the production due to exhaustion. Although some of Cukor's scenes were later reshot, Selznick estimated that "three solid reels" of his work remained in the picture. As of the end of principal photography, Cukor had undertaken eighteen days of filming, Fleming ninety-three, and Wood twenty-four.[8]

Cinematographer Lee Garmes began the production, but on March 11, 1939—after a month of shooting footage that Selznick and his associates regarded as "too dark"—was replaced with Ernest Haller, working with Technicolor cinematographer Ray Rennahan. Garmes completed the first third of the film—mostly everything prior to Melanie having the baby—but did not receive a credit.[22] Most of the filming was done on "the back forty" of Selznick International with all the location scenes being photographed in California, mostly in Los Angeles County or neighboring Ventura County.[23] Tara, the fictional Southern plantation house, existed only as a plywood and papier-mâché facade built on the "back forty" California studio lot.[24] For the burning of Atlanta, other false facades were built in front of the "back forty"'s many abandoned sets, and Selznick himself operated the controls for the explosives that burned them down.[4] Sources at the time put the estimated production costs at $3.85 million, making it the second most expensive film made up to that point, with only Ben-Hur (1925) having cost more.[25][nb 4]

Although legend persists that the Hays Office fined Selznick $5,000 for using the word "damn" in Butler's exit line, in fact the Motion Picture Association board passed an amendment to the Production Code on November 1, 1939, that forbade use of the words "hell" or "damn" except when their use "shall be essential and required for portrayal, in proper historical context, of any scene or dialogue based upon historical fact or folklore ... or a quotation from a literary work, provided that no such use shall be permitted which is intrinsically objectionable or offends good taste." With that amendment, the Production Code Administration had no further objection to Rhett's closing line.[27]

Music

To compose the score, Selznick chose Max Steiner, with whom he had worked at RKO Pictures in the early 1930s. Warner Bros.—who had contracted Steiner in 1936—agreed to lend him to Selznick. Steiner spent twelve weeks working on the score, the longest period that he had ever spent writing one, and at two hours and thirty-six minutes long it was also the longest that he had ever written. Five orchestrators were hired, including Hugo Friedhofer, Maurice de Packh, Bernard Kaun, Adolph Deutsch and Reginald Bassett. The score is characterized by two love themes, one for Ashley's and Melanie's sweet love and another that evokes Scarlett's passion for Ashley, though notably there is no Scarlett and Rhett love theme. Steiner drew considerably on folk and patriotic music, which included Stephen Foster tunes such as "Louisiana Belle," "Dolly Day," "Ringo De Banjo," "Beautiful Dreamer," "Old Folks at Home," and "Katie Belle," which formed the basis of Scarlett's theme; other tunes that feature prominently are: "Marching through Georgia" by Henry Clay Work, "Dixie," "Garryowen" and "The Bonnie Blue Flag." The theme that is most associated with the film today is the melody that accompanies Tara, the O'Hara plantation; in the early 1940s, "Tara's Theme" formed the musical basis of the song "My Own True Love" by Mack David. In all, there are ninety-nine separate pieces of music featured in the score. Due to the pressure of completing on time, Steiner received some assistance in composing from Friedhofer, Deutsch and Heinz Roemheld, and in addition, two short cues—by Franz Waxman and William Axt—were taken from scores in the MGM library.[28]

Release

Preview, premiere and initial release

On September 9, 1939, Selznick, his wife, Irene, investor John "Jock" Whitney and film editor Hal Kern drove out to Riverside, California to preview it at the Fox Theatre. The film was still a rough cut at this stage, missing completed titles and lacking special optical effects. It ran for four hours and twenty-five minutes, but would later be cut down to under four hours for its proper release. A double bill of Hawaiian Nights and Beau Geste was playing, and after the first feature it was announced that the theater would be screening a preview; the audience were informed they could leave but would not be readmitted once the film had begun, nor would phone calls be allowed once the theater had been sealed. When the title appeared on the screen the audience cheered, and after it had finished it received a standing ovation.[8][29] In his biography of Selznick, David Thomson wrote that the audience's response before the film had even started "was the greatest moment of [Selznick's] life, the greatest victory and redemption of all his failings",[30] with Selznick describing the preview cards as "probably the most amazing any picture has ever had."[31] When Selznick was asked by the press in early September how he felt about the film, he said: "At noon I think it's divine, at midnight I think it's lousy. Sometimes I think it's the greatest picture ever made. But if it's only a great picture, I'll still be satisfied."[25]

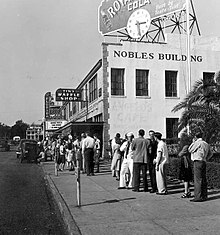

About 300,000 people came out in Atlanta for the film's premiere at the Loew's Grand Theatre on December 15, 1939. It was the climax of three days of festivities hosted by Mayor William B. Hartsfield, which included a parade of limousines featuring stars from the film, receptions, thousands of Confederate flags and a costume ball. Eurith D. Rivers, the governor of Georgia, declared December 15 a state holiday. An estimated three hundred thousand residents and visitors to Atlanta lined the streets for up to seven miles to watch a procession of limousines bring the stars from the airport. Only Leslie Howard and Victor Fleming chose not to attend: Howard had returned to England due to the outbreak of World War II, and Fleming had fallen out with Selznick and declined to attend any of the premieres.[25][31] Hattie McDaniel was also absent, as she and the other black actors from the film were prevented from attending the premiere due to Georgia's Jim Crow laws, which would have kept them from sitting with the white members of the cast. Upon learning that McDaniel had been barred from the premiere, Clark Gable threatened to boycott the event, but McDaniel convinced him to attend.[32] President Jimmy Carter would later recall it as "the biggest event to happen in the South in my lifetime."[33] Premieres in New York and Los Angeles followed, the latter attended by some of the actresses that had been considered for the part of Scarlett, among them Paulette Goddard, Norma Shearer and Joan Crawford.[31]

From December 1939 to July 1940, the film played only advance-ticket road show engagements at a limited number of theaters at prices upwards of $1—more than double the price of a regular first-run feature—with MGM collecting an unprecedented 70 percent of the box office receipts (as opposed to the typical 30–35 percent of the period). After reaching saturation as a roadshow, MGM revised its terms to a 50 percent cut and halved the prices, before it finally entered general release in 1941 at "popular" prices.[34] Along with its distribution and advertising costs, total expenditure on the film was as high as $7 million.[31][35]

Later releases

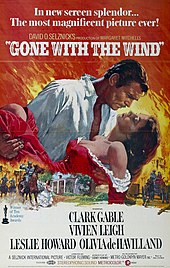

In 1942, Selznick liquidated his company for tax reasons, and sold his share in Gone with the Wind to his business partner, John Whitney, for $500,000. In turn, Whitney sold it on to MGM for $2.8 million, so that the studio more or less owned the film outright.[35] MGM immediately re-released the film in spring 1942,[16] and again in 1947 and 1954;[8] the 1954 reissue was the first time the film was shown in widescreen, compromising the original Academy ratio and cropping the top and bottom to an aspect ratio of 1.75:1. In doing so, a number of shots were optically re-framed and cut into the three-strip camera negatives, forever altering five shots in the film.[36] A 1961 release commemorated the centennial anniversary of the start of the Civil War, and included a gala "premiere" at the Loew's Grand Theater. It was attended by Selznick and many other stars of the film, including Vivien Leigh and Olivia de Havilland;[37] Clark Gable had died the previous year.[38] For its 1967 re-release, it was blown up to 70mm,[8] and issued with updated poster artwork featuring Gable—with his white shirt ripped open—holding Leigh against a backdrop of orange flames.[37] There were further re-releases in 1971, 1974 and 1989; for the fiftieth anniversary reissue in 1989, it was given a complete audio and video restoration. It was released theatrically one more time in the United States, in 1998.[39][40] In 2013, a 4K digital restoration was released in the United Kingdom to coincide with Vivien Leigh's centenary.[41] In 2014, special screenings were scheduled over a two-day period at theaters across the United States to coincide with the film's 75th anniversary.[42]

Television and home video

The film received its world television premiere on the HBO cable network on June 11, 1976, and played on the channel for a total of fourteen times throughout the rest of the month. It made its network television debut in November later that year: NBC paid $5 million for a one-off airing, and it was broadcast in two parts on successive evenings. It became at that time the highest-rated television program ever presented on a single network, watched by 47.5 percent of the households sampled in America, and 65 percent of television viewers, still the record for the highest rated film to ever air on television. In 1978, CBS signed a deal worth $35 million to broadcast the film twenty times over as many years.[16][40] Turner Entertainment acquired the MGM film library in 1986, but the deal did not include the television rights to Gone with the Wind, which were still held by CBS. A deal was struck in which the rights were returned to Turner Entertainment and CBS's broadcast rights to The Wizard of Oz were extended.[16] It was used to launch two cable channels owned by Turner Broadcasting System: Turner Network Television (1988) and Turner Classic Movies (1994).[43][44] It debuted on videocassette in March 1985, where it placed second in the sales charts,[16] and has since been released on DVD and Blu-ray Disc formats.[37]

Reception

Critical response

Gone with the Wind was well received upon its release, with most consumer magazines and newspapers generally giving it excellent reviews.[8] However, while its production values, technical achievements, and scale of ambition were universally recognized, some of the more notable reviewers of the time found the film to be dramatically lacking. Frank S. Nugent for The New York Times best summed up the general sentiment by acknowledging that while it was the most ambitious film production made up to that point, it probably was not the greatest film ever made, but he nevertheless found it to be an "interesting story beautifully told".[45] Franz Hoellering of The Nation was of the same opinion: "The result is a film which is a major event in the history of the industry but only a minor achievement in motion-picture art. There are moments when the two categories meet on good terms, but the long stretches between are filled with mere spectacular efficiency."[46]

The result is a film which is a major event in the history of the industry but only a minor achievement in motion-picture art.

— Franz Hoellering, reviewer for The Nation

While the film was praised for its fidelity to the novel,[45] this aspect was also singled out as the main factor in contributing to the bloated running time, which many critics felt was to the detriment of the overall dramatic impact.[47] John C. Flinn wrote for Variety that Selznick had "left too much in", and that as entertainment, the film would have benefited if repetitious scenes and dialog from the latter part of the story had been trimmed.[47] The Manchester Guardian felt that the film's one serious drawback was that the story lacked the epic quality to justify the outlay of time and found the second half, which focuses on Scarlett's "irrelevant marriages" and "domestic squabbles," mostly superfluous, and the sole reason for their inclusion had been "simply because Margaret Mitchell wrote it that way". The Guardian believed that if "the story had been cut short and tidied up at the point marked by the interval, and if the personal drama had been made subservient to a cinematic treatment of the central theme—the collapse and devastation of the Old South—then Gone With the Wind might have been a really great film."[48] Likewise, Hoellering also found the second half of the film to be weaker than the first half: identifying the Civil War to be the driving force of the first part while the characters dominate in the second part, he concluded this is where the main fault of the picture lay, commenting that "the characters alone do not suffice". Despite many excellent scenes, he considered the drama to be unconvincing and that the "psychological development" had been neglected.[46]

Much of the praise was reserved for the casting, with Vivien Leigh in particular being singled out for her performance as Scarlett. Nugent described her as the "pivot of the picture" and believed her to be "so perfectly designed for the part by art and nature that any other actress in the role would be inconceivable".[45] Similarly, Hoellering found her "perfect" in "appearance and movements"; he felt her acting best when she was allowed to "accentuate the split personality she portrays" and thought she was particularly effective in such moments of characterization like the morning after the marital rape scene.[46] Flinn also found Leigh suited to the role physically and felt she was best in the scenes where she displays courage and determination, such as the escape from Atlanta and when Scarlett kills a Yankee deserter.[47] Leigh won in the Best Actress category for her performance at the 1939 New York Film Critics Circle Awards.[49] Of Clark Gable's performance as Rhett Butler, Flinn felt the characterization was "as close to Miss Mitchell's conception—and the audience's—as might be imagined",[47] a view which Nugent concurred with,[45] although Hoellering felt that Gable didn't quite convince in the closing scenes, as Rhett walks out on Scarlett in disgust.[46] Of the other principal cast members, both Hoellering and Flinn found Leslie Howard to be "convincing" as the weak-willed Ashley, with Flinn identifying Olivia de Havilland as a "standout" as Melanie;[46][47] Nugent was also especially taken with de Havilland's performance, describing it as a "gracious, dignified, tender gem of characterization".[45] Hattie McDaniel's performance as Mammy was singled out for praise by many critics: Nugent believed she gave the best performance in the film after Vivien Leigh,[45] with Flinn placing it third after Leigh's and Gable's performances.[47]

Academy Awards

At the 12th Academy Awards, Gone with the Wind set a record for Academy Award wins and nominations, winning in eight of the competitive categories it was nominated in, from a total of thirteen nominations. It won for Best Picture, Best Actress, Best Supporting Actress, Best Director, Best Screenplay, Best Cinematography, Best Interior Decoration, and Best Editing, and received two further honorary awards for its use of equipment and color (it also became the first color film to win Best Picture).[50][51] Its record of eight competitive wins stood until Gigi (1958) won nine, and its overall record of ten was broken by Ben-Hur (1959) which won eleven.[52] Gone with the Wind also held the record for most nominations until All About Eve (1950) secured fourteen.[9] It was the longest American sound film made up to that point, and may still hold the record of the longest Best Picture winner depending on how it is interpreted.[53] The running time for Gone with the Wind is just under 221 minutes, while Lawrence of Arabia (1962) runs for just over 222 minutes; however, including the overture, intermission, entr'acte, and exit music, Gone with the Wind lasts for 234 minutes (although some sources put its full length at 238 minutes) while Lawrence of Arabia comes in slightly shorter at 232 minutes with its additional components.[54][55]

Hattie McDaniel became the first African-American to win an Academy Award—beating out her co-star Olivia de Havilland who was also nominated in the same category—but was racially segregated from her co-stars at the awards ceremony at the Coconut Grove; she and her escort were made to sit at a separate table at the back of the room.[56] Meanwhile, screenwriter Sidney Howard became the first posthumous Oscar winner and Selznick personally received the Irving G. Thalberg Memorial Award for his career achievements.[9][50]

African-American reaction

Black commentators criticised the film for its depiction of black people and as a glorification of slavery. Carlton Moss, a black dramatist, complained in an open letter that whereas The Birth of a Nation was a "frontal attack on American history and the Negro people", Gone with the Wind was a "rear attack on the same". He went on to dismiss it as a "nostalgic plea for sympathy for a still living cause of Southern reaction". Moss further criticized the stereotypical black characterizations, such as the "shiftless and dull-witted Pork", the "indolent and thoroughly irresponsible Prissy", Big Sam's "radiant acceptance of slavery", and Mammy with her "constant haranguing and doting on every wish of Scarlett".[57] Following Hattie McDaniel's Oscar win, Walter Francis White, leader of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People, accused her of being an Uncle Tom. McDaniel responded that she would "rather make seven hundred dollars a week playing a maid than seven dollars being one"; she further questioned White's qualification to speak on behalf of blacks, since he was light-skinned and only one-eighth black.[56]

Opinion in the black community was generally divided upon release, with the film being called by some a "weapon of terror against black America" and an insult to black audiences, and demonstrations were held in various cities.[56] Even so, some sections of the black community recognized McDaniel's achievements to be representative of progression: some African-Americans crossed picket lines and praised McDaniel's warm and witty characterization, while others hoped that the industry's recognition of her work would lead to increased visibility on screen for other black actors. In its editorial congratulation to McDaniel on winning her Academy Award, Opportunity: A Journal of Negro Life used the film as reminder of the "limit" put on black aspiration by old prejudices.[56][57] Malcolm X would later recall that "when Butterfly McQueen went into her act, I felt like crawling under the rug".[58]

Audience response

Upon its release, Gone with the Wind broke attendance records everywhere. At the Capitol Theatre in New York alone, it was averaging eleven thousand admissions per day in late December,[34] and within four years of its release had sold an estimated sixty million tickets across the United States—sales equivalent to just under half the population at the time.[59][60] It repeated its success overseas, and was a sensational hit during the Blitz in London, opening in April 1940 and playing for four years.[61] By the time MGM withdrew it from circulation at the end of 1943 its worldwide distribution had returned a gross rental (the studio's share of the box office gross) of $32 million, making it the most profitable film ever made up to that point.[9][16]

Even though it earned its investors roughly twice as much as the previous record-holder, The Birth of a Nation,[62][63] the box-office performances of the two films were likely much closer. The bulk of the earnings from Gone with the Wind came from its roadshow and first-run engagements, which represented 70 percent and 50 percent of the box-office gross respectively, before entering general release (which at the time typically saw the distributor's share set at 30–35 percent of the gross).[34] In the case of The Birth of a Nation, its distributor, Epoch, sold off many of its distribution territories on a "states rights" basis—which typically amounted to 10 percent of the box-office gross—and Epoch's accounts are only indicative of its own profits from the film, and not the local distributors. Carl E. Milliken, secretary of the Motion Picture Producers and Distributors Association, estimated that The Birth of a Nation had been seen by fifty million people by 1930.[64][65]

When it was re-released in 1947, it earned an impressive $5 million rental in the United States and Canada, and was one of the top ten releases of the year.[35][62] Successful re-releases in 1954 and 1961 enabled it to retain its position as the industry's top earner, despite strong challenges from more recent films such as Ben-Hur,[66] but it was finally overtaken by The Sound of Music in 1966.[67] The 1967 reissue was unusual in that MGM opted to roadshow it, a decision that turned it into the most successful re-release in the history of the industry. It generated a box-office gross of $68 million, making it MGM's most lucrative picture after Doctor Zhivago from the latter half of the decade.[68] MGM earned a rental of $41 million from the release,[69] with the U.S. and Canadian share amounting to over $30 million, placing it second only to The Graduate for that year.[62][69] Including its $6.7 million rental from the 1961 reissue,[70] it was the fourth highest-earner of the decade in the North American market, with only The Sound of Music, The Graduate and Doctor Zhivago making more for their distributors.[62] A further re-release in 1971 allowed it to briefly recapture the record from The Sound of Music, bringing its total worldwide gross rental to about $116 million by the end of 1971—more than trebling its earnings from its initial release—before losing the record again the following year to The Godfather.[40][71]

Across all releases, it is estimated that Gone with the Wind has sold over 200 million tickets in the United States and Canada,[59] and 35 million tickets in the United Kingdom,[72] generating more theater admissions in those territories than any other film.[73][74] In total, Gone with the Wind has grossed over $390 million globally at the box office;[75] in 2007 Turner Entertainment estimated the gross to be equivalent to approximately $3.3 billion when adjusted for inflation to current prices,[9] while Guinness World Records arrived at a figure of $3.44 billion in 2014, making it the most successful film in cinema history.[76]

The film remains immensely popular with audiences into the 21st century, having been voted the most popular film in two nationwide polls of Americans undertaken by Harris Interactive in 2008, and again in 2014. The market research firm surveyed over two thousand U.S. adults, with the results weighted by age, sex, race/ethnicity, education, region and household income so their proportions matched the composition of the adult population.[77][78]

Critical re-evaluation

- AFI's 100 Years...100 Movies – #4

- AFI's 100 Years...100 Passions – #2

- AFI's 100 Years...100 Heroes and Villains

- Rhett Butler, Hero – Nominated

- Scarlett O'Hara, Hero – Nominated

- AFI's 100 Years...100 Movie Quotes:

- "Frankly, my dear, I don't give a damn." – #1

- "After all, tomorrow is another day!" – #31

- "As God is my witness, I'll never be hungry again." – #59

- "Fiddle-dee-dee." – Nominated

- "I don't know nothin' 'bout birthin' babies." – Nominated

- AFI's 100 Years of Film Scores – #2

- AFI's 100 Years...100 Cheers – #43

- AFI's 100 Years...100 Movies (10th Anniversary Edition) – #6

- AFI's 10 Top 10 – #4 Epic film

American Film Institute[79]

In revisiting the film in the 1970s, Arthur Schlesinger noted that Hollywood films generally age well, revealing an unexpected depth or integrity, but in the case of Gone with the Wind time has not treated it kindly.[80] Richard Schickel posits that one measure of a film's quality is to ask what you can remember of it, and the film falls down in this regard: unforgettable imagery and dialogue are simply not present.[81] Stanley Kauffmann, likewise, also found the film to be a largely forgettable experience, claiming he could only remember two scenes vividly.[82] Both Schickel and Schlesinger put this down to it being "badly written", in turn describing the dialogue as "flowery" and possessing a "picture postcard" sensibility.[80][81] Schickel also believes the film fails as popular art, in that it has limited rewatch value—a sentiment that Kauffmann also concurs with, stating that having watched it twice he hopes "never to see it again: twice is twice as much as any lifetime needs".[81][82] Both Schickel and Andrew Sarris identify the film's main failing is in possessing a producer's sensibility rather than an artistic one: having gone through so many directors and writers the film does not carry a sense of being "created" or "directed", but rather having emerged "steaming from the crowded kitchen", where the main creative force was a producer's obsession in making the film as literally faithful to the novel as possible.[81][83]

Sarris concedes that despite its artistic failings, the film does hold a mandate around the world as the "single most beloved entertainment ever produced".[83] Judith Crist observes that, kitsch aside, the film is "undoubtedly still the best and most durable piece of popular entertainment to have come off the Hollywood assembly lines", the product of a showman with "taste and intelligence".[84] Schlesinger notes that the first half of the film does have a "sweep and vigor" that aspire to its epic theme, but—finding agreement with the film's contemporary criticisms—the personal lives take over in the second half, and it ends up losing its theme in unconvincing sentimentality.[80] Kauffmann also finds interesting parallels with The Godfather, which had just replaced Gone with the Wind as the highest-grosser at the time: both were produced from "ultra-American" best-selling novels, both live within codes of honor that are romanticized, and both in essence offer cultural fabrication or revisionism.[82]

The critical perception of the film has shifted in the intervening years, which resulted in it being ranked 235th in Sight & Sound's prestigious decennial critics poll in 2012,[85] and in 2015 sixty-two international film critics polled by the BBC voted it the 97th best American film.[86]

Industry recognition

The film has featured in several high-profile industry polls: in 1977 it was voted the most popular film by the American Film Institute (AFI), in a poll of the organization's membership;[8] the AFI also ranked the film fourth on its "100 Greatest Movies" list in 1998,[87] with it slipping down to sixth place in the tenth anniversary edition in 2007.[88] Film directors ranked it 322nd in the 2012 edition of the decennial Sight & Sound poll,[85] and in 2016 it was selected as the ninth best "directorial achievement" in a Directors Guild of America members poll.[89] In 2014, it placed fifteenth in an extensive poll undertaken by The Hollywood Reporter, which ballotted every studio, agency, publicity firm and production house in the Hollywood region.[90] Gone with the Wind was selected for preservation in the U.S. National Film Registry in 1989.[9]

Analysis

Racial criticism

Gone with the Wind has been criticized as having perpetuated Civil War myths and black stereotypes.[91] David Reynolds writes that "The white women are elegant, their menfolk noble or at least dashing. And, in the background, the black slaves are mostly dutiful and content, clearly incapable of an independent existence." Reynolds likened Gone with the Wind to The Birth of a Nation and other re-imaginings of the South during the era of segregation, in which white Southerners are portrayed as defending traditional values and the issue of slavery is largely ignored.[58] The film has been described as a "regression" that promotes the myth of the black rapist and the honourable and defensive role of the Ku Klux Klan during Reconstruction,[92] and as a "social propaganda" film offering a "white supremacist" view of the past.[91] From 1972 to 1996, the Atlanta Historical Society held a number of Gone with the Wind exhibits, among them a 1994 exhibit titled, "Disputed Territories: Gone with the Wind and Southern Myths". One of the questions explored by the exhibit was "How True to Life Were the Slaves in GWTW?" This section showed slave experiences were diverse and concluded that the "happy darky" was a myth, as was the belief that all slaves experienced violence and brutality.[93]

Despite factual inaccuracies in its depiction of the Reconstruction period, it nevertheless reflects contemporary interpretations common throughout the early 20th century. One pervasive viewpoint argued by academics is reflected in a brief scene in which Mammy fends off a leering freedman: a government official can be heard offering bribes to the emancipated slaves for their votes. The clear inference is that freedmen are ignorant about politics and unprepared for freedom, unwittingly becoming the tools of corrupt Reconstruction officials. While perpetuating some Lost Cause myths, the film makes concessions in regards to others. After the attack on Scarlett in the shanty town, a group of men including Scarlett's husband Frank, Rhett Butler and Ashley raid the town; in the novel they belong to the Ku Klux Klan, representing the common trope of protecting the white woman's virtue, but the filmmakers consciously neutralize the presence of the Klan in the film by referring to it only as a "political meeting".[94]

Thomas Cripps has argued that the film in some respects undercuts racial stereotypes;[95] in particular, the film created greater engagement between Hollywood and black audiences,[95] with dozens of movies making small gestures in recognition of the emerging trend.[57] Only a few weeks after its initial run, a story editor at Warner wrote a memo to Walter Wanger about Mississippi Belle, a script that contained the worst excesses of plantation films, suggesting that Gone with the Wind had made the film "unproducible". More than any film since The Birth of a Nation, it unleashed a variety of social forces that foreshadowed an alliance of white liberals and blacks who encouraged the expectation that blacks would one day achieve equality. According to Cripps, the film eventually became a template for measuring social change.[57]

Depiction of marital rape

One of the most notorious and widely condemned scenes in Gone with the Wind depicts what is now legally defined as "marital rape".[96][97] The scene begins with Scarlett and Rhett at the bottom of the staircase, where he begins to kiss her, refusing to be told 'no' by the struggling and frightened Scarlett;[98][99] Rhett overcomes her resistance and carries her up the stairs to the bedroom,[98][99] where the audience is left in no doubt that she will "get what's coming to her".[100] The next scene, the following morning, shows Scarlett glowing with barely suppressed sexual satisfaction;[98][99][100] Rhett apologizes for his behavior, blaming it on his drinking.[98] The scene has been accused of combining romance and rape by making them indistinguishable from each other,[98] and of reinforcing a notion about forced sex: that women secretly enjoy it, and it is an acceptable way for a man to treat his wife.[100]

Molly Haskell has argued that nevertheless, women are mostly uncritical of the scene, and that by and large it is consistent with what women have in mind when they fantasize about being raped. Their fantasies revolve around love and romance rather than forced sex; they assume that Scarlett was not an unwilling sexual partner and wanted Rhett to take the initiative and insist on having sexual intercourse.[101]

Legacy

In popular culture

Gone with the Wind and its production have been explicitly referenced, satirized, dramatized and analyzed on numerous occasions across a range of media, from contemporaneous works such as Second Fiddle—a 1939 film spoofing the "search for Scarlett"—to current television shows, such as The Simpsons.[91][102][103] The Scarlett O'Hara War (a 1980 television dramatization of the casting of Scarlett),[104] Moonlight and Magnolias (a 2007 play by Ron Hutchinson that dramatizes Ben Hecht's five-day re-write of the script),[105] and "Went with the Wind!" (a sketch on The Carol Burnett Show that parodied the film in the aftermath of its television debut in 1976) are among the more noteworthy examples of its enduring presence in popular culture.[16] It was also the subject of a 1988 documentary, The Making of a Legend: Gone with the Wind, detailing the film's difficult production history.[106] In 1990, the United States Postal Service issued a stamp depicting Clark Gable and Vivien Leigh embracing in a scene from the film.[107]

Sequel

Following publication of her novel, Margaret Mitchell was inundated with requests for a sequel but claimed to not have a notion of what happened to Scarlett and Rhett, and that she had "left them to their ultimate fate". Mitchell continued to resist pressure from Selznick and MGM to write a sequel until her death in 1949. In 1975, her brother, Stephens Mitchell (who assumed control of her estate), authorized a sequel to be jointly produced by MGM and Universal Studios on a budget of $12 million. Anne Edwards was commissioned to write the sequel as a novel which would then be adapted into a screenplay, and published in conjunction with the film's release. Edwards submitted a 775-page manuscript entitled Tara, The Continuation of Gone with the Wind, set between 1872 and 1882 focusing on Scarlett's divorce from Rhett; MGM was not satisfied with the story and the deal collapsed.[16]

The idea was revived in the 1990s, when a sequel was finally produced in 1994, in the form of a television miniseries. Scarlett was based upon the novel by Alexandra Ripley, itself a sequel to Mitchell's book. British actors Joanne Whalley and Timothy Dalton were cast as Scarlett and Rhett, and the series follows Scarlett's relocation to Ireland after again becoming pregnant by Rhett.[108]

See also

References

Explanatory notes

- ^ Loews was the parent company of MGM.[1]

- ^ a b The credits at the start of the film contain an error: George Reeves is listed "as Brent Tarleton", but plays Stuart, while Fred Crane is listed "as Stuart Tarleton", but plays Brent.[2]

- ^ From a private letter from journalist and on-set technical advisor Susan Myrick to Margaret Mitchell in February 1939:

- George [Cukor] finally told me all about it. He hated [leaving the production] very much he said but he could not do otherwise. In effect he said he is an honest craftsman and he cannot do a job unless he knows it is a good job and he feels the present job is not right. For days, he told me he has looked at the rushes and felt he was failing... the thing did not click as it should. Gradually he became convinced that the script was the trouble... David [Selznick], himself, thinks HE is writing the script... And George has continually taken script from day to day, compared the [Oliver] Garrett-Selznick version with the [Sidney] Howard, groaned and tried to change some parts back to the Howard script. But he seldom could do much with the scene... So George just told David he would not work any longer if the script was not better and he wanted the Howard script back. David told George he was a director—not an author and he (David) was the producer and the judge of what is a good script... George said he was a director and a damn good one and he would not let his name go out over a lousy picture... And bull-headed David said "OK get out!"[19]

- ^ Time also reports that Hell's Angels (1930)—directed by Howard Hughes—cost more, but this was later revealed to be a fallacy; the accounts for Hell's Angels show it cost $2.8 million, but Hughes publicized it as costing $4 million, selling it to the media as the most expensive film ever made up to that point.[26]

Citations

- ^ Gomery, Douglas; Pafort-Overduin, Clara (2011). Movie History: A Survey (2nd ed.). Taylor & Francis. p. 144. ISBN 9781136835254.

- ^ a b "Gone With the Wind". The American Film Institute Catalog of Motion Pictures. American Film Institute. Retrieved January 12, 2013.

- ^ Noland, Claire (April 8, 2014). "Mary Anderson dies at 96; actress had role in 'Gone With the Wind'". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved April 8, 2014.

- ^ a b c d e f Friedrich, Otto (1986). City of Nets: A Portrait of Hollywood in the 1940s. Berkeley and Los Angeles: University of California Press. pp. 17–21. ISBN 978-0-520-20949-7.

- ^ "The Book Purchase". Gone With The Wind Online Exhibit. University of Texas at Austin: Harry Ransom Center. Archived from the original on February 24, 2014.

{{cite web}}:|archive-date=/|archive-url=timestamp mismatch; June 2, 2014 suggested (help) - ^ "The Search for Scarlett: Chronology". Gone With The Wind Online Exhibit. University of Texas at Austin: Harry Ransom Center. Archived from the original on February 23, 2014.

{{cite web}}:|archive-date=/|archive-url=timestamp mismatch; June 2, 2014 suggested (help) - ^ a b c d e Lambert, Gavin (February 1973). "The Making of Gone With The Wind, Part I". The Atlantic Monthly. Retrieved March 7, 2013.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k "Gone with the Wind (1939) – Notes". TCM database. Turner Classic Movies. Retrieved January 16, 2013.

- ^ a b c d e f g Miller, Frank; Stafford, Jeff. "Gone with the Wind (1939) – Articles". TCM database. Turner Classic Movies. Archived from the original on September 26, 2013.

- ^ "The Search for Scarlett: Girls Tested for the Role of Scarlett". Gone With The Wind Online Exhibit. University of Texas at Austin: Harry Ransom Center. Archived from the original on January 5, 2014.

- ^ Haver, Ronald (1980). David O. Selznick's Hollywood. New York: Alfred A. Knopf. ISBN 978-0-394-42595-5.

- ^ Pratt, William (1977). Scarlett Fever. New York: Macmillan Publishers. pp. 73–74, 81–83. ISBN 978-0-02-598560-5.

- ^ Walker, Marianne (2011). Margaret Mitchell and John Marsh: The Love Story Behind Gone With the Wind. Peachtree Publishers. pp. 405–406. ISBN 978-1-56145-617-8.

- ^ Selznick, David O. (January 7, 1939). "The Search for Scarlett: Vivien Leigh – Letter from David O. Selznick to Ed Sullivan". Gone With The Wind Online Exhibit. University of Texas at Austin: Harry Ransom Center. Archived from the original on October 28, 2013.

- ^ a b Yeck, Joanne (1984). Dictionary of Literary Biography. Vol. American Screenwriters. Gale.

{{cite encyclopedia}}: Missing or empty|title=(help) - ^ a b c d e f g h i Bartel, Pauline (1989). The Complete Gone with the Wind Trivia Book: The Movie and More. Taylor Trade Publishing. pp. 64–69, 127 & 161–172. ISBN 978-0-87833-619-7.

- ^ a b Selznick, David O. (1938–1939). Behlmer, Rudy (ed.). Memo from David O. Selznick: the creation of Gone with the wind and other motion picture classics, as revealed in the producer's private letters, telegrams, memorandums, and autobiographical remarks. New York: Modern Library (published 2000). pp. 179–180 & 224–225. ISBN 978-0-375-75531-6.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - ^ MacAdams, William (1990). Ben Hecht. New York: Barricade Books. pp. 199–201. ISBN 978-1-56980-028-7.

- ^ a b Myrick, Susan (1982). White Columns in Hollywood: Reports from the GWTW Sets. Macon, Georgia: Mercer University Press. pp. 126–127. ISBN 978-0-86554-044-6.

- ^ Eyman, Scott (2005). Lion of Hollywood: The Life and Legend of Louis B. Mayer. Robson Books. pp. 258–259. ISBN 978-1-86105-892-8.

- ^ Capua, Michelangelo (2003). Vivien Leigh: A Biography. McFarland & Company. pp. 59–61. ISBN 978-0-7864-1497-0.

- ^ Turner, Adrian (1989). A celebration of Gone with the wind. Dragon's World. p. 114.

- ^ Molt, Cynthia Marylee (1990). Gone with the Wind on Film: A Complete Reference. Jefferson, NC: McFarland & Company. pp. 272–281. ISBN 978-0-89950-439-1.

- ^ Bridges, Herb (1998). The Filming of Gone with the Wind. Mercer University Press. PT4. ISBN 978-0-86554-621-9.

- ^ a b c "Cinema: G With the W". Time. December 25, 1939. pp. 9171, 762137–1, 00.html 1–9171, 762137–2, 00.html 2 & 9171, 762137–7, 00.html 7. Retrieved July 6, 2011.

- ^ Eyman, Scott (1997). The speed of sound: Hollywood and the talkie revolution, 1926–1930. Simon & Schuster. p. 253. ISBN 978-0-684-81162-8.

- ^ Leff, Leonard J.; Simmons, Jerold L. (2001). The Dame in the Kimono: Hollywood, Censorship, and the Production Code. University Press of Kentucky. p. 108.

- ^ MacDonald, Laurence E. (1998). The Invisible Art of Film Music: A Comprehensive History. Scarecrow Press. pp. 52–53. ISBN 978-1-880157-56-5.

- ^ Bell, Alison (June 25, 2010). "Inland Empire cities were once 'in' with Hollywood for movie previews". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved January 25, 2013.

- ^ Thomson, David (1992). Showman: The Life of David O. Selznick. New York: Knopf. ISBN 978-0-394-56833-1.

- ^ a b c d Lambert, Gavin (March 1973). "The Making of Gone With The Wind, Part II". The Atlantic Monthly. Vol. 265, no. 6. pp. 56–72. Retrieved January 25, 2013.

- ^ Harris, Warren G. (2002). Clark Gable: A Biography. Harmony Books. p. 211.

- ^ Cravens, Hamilton (2009). Great Depression: People and Perspectives. Perspectives in American Social History. ABC-CLIO. p. 221. ISBN 978-1-59884-093-3.

- ^ a b c Schatz, Thomas (1999) [1st. pub. 1997]. Boom and Bust: American Cinema in the 1940s. Vol. Volume 6 of History of the American Cinema. University of California Press. pp. 65–66. ISBN 978-0-520-22130-7.

{{cite book}}:|volume=has extra text (help) - ^ a b c Shearer, Lloyd (October 26, 1947). "GWTW: Supercolossal Saga of an Epic". The New York Times. Retrieved July 14, 2012.

- ^ Haver, Ronald (1993). David O. Selznick's Gone with the wind. New York: Random House. pp. 84–85.

- ^ a b c Brown, Ellen F.; Wiley, John, Jr. (2011). Margaret Mitchell's Gone With the Wind: A Bestseller's Odyssey from Atlanta to Hollywood. Taylor Trade Publications. pp. 287, 293 & 322. ISBN 978-1-58979-527-3.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Olson, James Stuart (2000). Historical Dictionary of the 1950s. Greenwood Publishing Group. p. 108. ISBN 978-0-313-30619-8.

- ^ Block, Alex Ben; Wilson, Lucy Autrey, eds. (2010). George Lucas's Blockbusting: A Decade-By-Decade Survey of Timeless Movies Including Untold Secrets of Their Financial and Cultural Success. HarperCollins. pp. 220–221. ISBN 978-0-06-177889-6.

- ^ a b c Krämer, Peter (2005). The New Hollywood: From Bonnie And Clyde To Star Wars. Short Cuts. Vol. 30. Wallflower Press. p. 46. ISBN 978-1-904764-58-8.

- ^ Andrew, Geoff. "Gone with the Wind". British Film Institute. Archived from the original on December 1, 2013.

- ^ Fristoe, Roger. "Gone with the Wind: 75th Anniversary – Screenings and Events". Turner Classic Movies. Retrieved September 28, 2014.

- ^ Clark, Kenneth R. (September 29, 1988). "Tnt Rides In On 'Gone With Wind'". Chicago Tribune. Retrieved January 29, 2013.

- ^ Robert, Osborne. "Robert Osborne on TCM's 15th Anniversary". Turner Classic Movies. Retrieved January 29, 2013.

- ^ a b c d e f Nugent, Frank S. (December 20, 1939). "The Screen in Review; David Selznick's 'Gone With the Wind' Has Its Long-Awaited Premiere at Astor and Capitol, Recalling Civil War and Plantation Days of South--Seen as Treating Book With Great Fidelity". The New York Times. Retrieved February 1, 2013.

- ^ a b c d e Hoellering, Franz (1939). "Gone With the Wind". The Nation (published December 16, 2008). Retrieved February 1, 2013.

- ^ a b c d e f Flinn, John C., Sr. (December 20, 1939). "Gone With the Wind". Variety. Archived from the original on February 24, 2013. Retrieved June 14, 2013.

{{cite news}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ "From the archive, 28 May 1940: Gone with the wind at the Gaiety". The Manchester Guardian (published May 28, 2010). May 28, 1940. Retrieved February 1, 2013.

- ^ "New York Film Critics Circle Awards – 1939 Awards". New York Film Critics Circle. Retrieved July 21, 2015.

- ^ a b "Results page – 1939 (12th)". Academy Awards database. Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences. Retrieved February 3, 2013.

- ^ Randall, David; Clark, Heather (February 24, 2013). "Oscars – cinema's Golden Night: The ultimate bluffer's guide to Hollywood's big night". The Independent. Retrieved March 7, 2013.

- ^ Cutler, David (February 22, 2013). Goldsmith, Belinda; Zargham, Mohammad (eds.). "Factbox : Key historical facts about the Academy Awards". Reuters. Retrieved March 7, 2013.

- ^ "Beyond the Page: Famous Quotes". Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences. Archived from the original on September 5, 2012. Retrieved March 8, 2013.

- ^ Dirks, Tim. "Academy Awards: Best Picture – Facts & Trivia". Filmsite.org. AMC Networks. p. 2. Retrieved March 7, 2013.

- ^ Kim, Wook (February 22, 2013). "17 Unusual Oscar Records – Longest Film (Running Time) to Win an Award: 431 Minutes". Time. Retrieved March 7, 2013.

- ^ a b c d Haskell, Molly (2010). Frankly, My Dear: Gone With the Wind Revisited. Icons of America. Yale University Press. pp. 213–214. ISBN 978-0-300-16437-4.

- ^ a b c d Lupack, Barbara Tepa (2002). Literary Adaptations in Black American Cinema: From Oscar Micheaux to Toni Morrison. University of Rochester Press. pp. 209–211. ISBN 978-1-58046-103-0.

- ^ a b Reynolds, David (2009). America, Empire of Liberty: A New History. Penguin UK. pp. 241–242. ISBN 978-0-14-190856-4.

- ^ a b Young, John (February 5, 2010). "'Avatar' vs. 'Gone With the Wind". Entertainment Weekly. Retrieved February 5, 2013.

- ^ "About the 1940 Census". Official 1940 Census Website. National Archives and Records Administration. Retrieved February 5, 2013.

- ^ "London Movie Doings". The New York Times. June 25, 1944. X3.

- ^ a b c d Finler, Joel Waldo (2003). The Hollywood Story. Wallflower Press. pp. 47, 356–363. ISBN 978-1-903364-66-6.

- ^ "Show Business: Record Wind". Time. February 19, 1940. Archived from the original on February 2, 2010. Retrieved January 19, 2013.

- ^ Stokes, Melvyn (2008). D.W. Griffith's the Birth of a Nation: A History of the Most Controversial Motion Picture of All Time. Oxford University Press. pp. 119 & 287. ISBN 978-0-19-533678-8.

- ^ Grieveson, Lee (2004). Policing Cinema: Movies and Censorship in Early-Twentieth-Century America. University of California Press. p. 308. ISBN 978-0-520-23966-1.

- ^ Thomas, Bob (August 1, 1963). "Movie Finances Are No Longer Hidden From Scrutiny". The Robesonian. Associated Press. p. 10.

- ^ Berkowitz, Edward D. (2010). Mass Appeal: The Formative Age of the Movies, Radio, and TV. Cambridge Essential Histories. Cambridge University Press. p. 160. ISBN 978-0-521-88908-7.

- ^ Hall, Sheldon; Neale, Stephen (2010). Epics, spectacles, and blockbusters: a Hollywood history. Wayne State University Press. pp. 181–182. ISBN 978-0-8143-3008-1.

- ^ a b Thomas, Bob (May 6, 1971). "Reissues playing big role in movie marketing today". The Register-Guard. Associated Press. p. 9E.

- ^ Kay, Eddie Dorman (1990). Box office champs: the most popular movies of the last 50 years. Random House Value Publishing. p. 92. ISBN 978-0-517-69212-7.

- ^ Akhmatova, Anna (1973). "Gone With the Wind". The Atlantic Monthly. Vol. 231. p. 2.

As of the end of 1971, GWTW stood as the all-time money-drawing movie, with a take of $116 million, and, with this year's reissues, it should continue to run ahead of the second place contender and all-time kaffee-mit-schlag spectacle.

- ^ "Gone with the Wind tops film list". BBC News. November 28, 2004. Retrieved June 9, 2011.

- ^ "Domestic Grosses – Adjusted for Ticket Price Inflation". Box Office Mojo. Retrieved February 8, 2013.

- ^ "The Ultimate Film Chart". British Film Institute. Retrieved August 9, 2009.

- ^ "Gone with the Wind". The Numbers. Nash Information Services. Retrieved February 8, 2013.

- ^ "Highest box office film gross – inflation adjusted". Guinness World Records. 2014. Retrieved February 9, 2015.

- ^ Corso, Regina A. (February 21, 2008). "Frankly My Dear, The Force is With Them as Gone With the Wind and Star Wars are the Top Two All Time Favorite Movies" (PDF) (Press release). Harris Interactive. Archived from the original (PDF) on July 14, 2013. Retrieved July 13, 2014.

{{cite press release}}:|archive-date=/|archive-url=timestamp mismatch; June 14, 2013 suggested (help) - ^ Shannon-Missal, Larry (December 17, 2014). "Gone but Not Forgotten: Gone with the Wind is Still America's Favorite Movie" (Press release). Harris Interactive. Archived from the original on December 28, 2014. Retrieved February 13, 2015.

- ^ "AFI's 100 Years...The Complete Lists". American Film Institute. Retrieved February 27, 2013.

- ^ a b c Schlesinger, Arthur (March 1973). "Time, alas, has treated Gone With the Wind cruelly". The Atlantic Monthly. Vol. 231, no. 3. p. 64. Retrieved February 16, 2013.

- ^ a b c d Schickel, Richard (March 1973). "Glossy, Sentimental, Chuckle-headed". The Atlantic Monthly. Vol. 231, no. 3. p. 71. Retrieved February 16, 2013.

- ^ a b c Kauffman, Stanley (March 1973). "The Romantic Is Still Popular". The Atlantic Monthly. Vol. 231, no. 3. p. 61. Retrieved February 16, 2013.

- ^ a b Sarris, Andrew (March 1973). "This moviest of All Movies". The Atlantic Monthly. Vol. 231, no. 3. p. 58. Retrieved February 16, 2013.

- ^ Crist, Judith (March 1973). "Glorious Excesses". The Atlantic Monthly. Vol. 231, no. 3. p. 67. Retrieved February 16, 2013.

- ^ a b "The Greatest Films Poll: Gone with the Wind". British Film Institute. 2012. Retrieved March 3, 2013.

- ^ BBC Culture (July 20, 2015). "The 100 greatest American films". BBC. Retrieved July 21, 2015.

- ^ "AFI's 100 Years...100 Movies". American Film Institute. June 1998. Retrieved February 27, 2013.

- ^ "AFI's 100 Years...100 Movies (10th Anniversary Edition)". American Film Institute. June 20, 2007. Retrieved February 27, 2013.

- ^ "The 80 Best-Directed Films". Directors Guild of America. Spring 2016. Retrieved May 4, 2016.

- ^ "Hollywood's 100 Favorite Films". The Hollywood Reporter. June 25, 2014. Retrieved July 13, 2014.

- ^ a b c Vera, Hernán; Gordon, Andrew Mark (2003). Screen Saviors: Hollywood Fictions of Whiteness. Rowman & Littlefield. p. viii & 102. ISBN 978-0-8476-9947-6.

- ^ Silk, Catherine; Silk, Johnk (1990). Racism and Anti-Racism in American Popular Culture: Portrayals of African-Americans in Fiction and Film. Manchester University Press. p. 141. ISBN 978-0-7190-3070-3.

- ^ Dickey, Jennifer W. (2014). A Tough Little Patch of History: Gone with the Wind and the politics of memory. University of Arkansas Press. p. 66. ISBN 978-1-55728-657-4.

- ^ Ruiz, W. Bryan Rommel (2010). American History Goes to the Movies: Hollywood and the American Experience. Taylor & Francis. p. 61. ISBN 978-0-203-83373-5.

- ^ a b Smyth, J.E. (2006). Reconstructing American Historical Cinema: From Cimarron to Citizen Kane. University Press of Kentucky. p. 164. ISBN 978-0-8131-7147-0.

- ^ White, John; Haenni, Sabine, eds. (2009). Fifty Key American Films. Routledge Key Guides. Routledge. p. 59. ISBN 978-0-203-89113-1.

- ^ Hickok, Eugene W., Jr. (1991). The Bill of Rights: Original Meaning and Current Understanding. University of Virginia Press. p. 103. ISBN 978-0-8139-1336-0.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ a b c d e Paludi, Michele A. (2012). The Psychology of Love. Women's Psychology. Vol. 2. ABC-CLIO. p. xxvi. ISBN 978-0-313-39315-0.

- ^ a b c Allison, Julie A.; Wrightsman, Lawrence S. (1993). Rape: The Misunderstood Crime (2 ed.). Sage Publications. p. 90. ISBN 978-0-8039-3707-9.

- ^ a b c Pagelow, Mildred Daley; Pagelow, Lloyd W. (1984). Family Violence. Praeger special studies. ABC-CLIO. p. 420. ISBN 978-0-275-91623-7.

- ^ Frus, Phyllis (2001). "Documenting Domestic Violence in American Films". In Slocum, J. David (ed.). Violence in American Cinema. Afi Film Readers. Routledge. p. 231. ISBN 978-0-415-92810-6.

- ^ Nugent, Frank S. (July 1, 1939). "Second Fiddle (1939) The Screen; 'Second Fiddle,' With Tyrone Power and Sonja Heine, Opens at the Roxy--Reports on New Foreign Films". The New York Times. Retrieved June 19, 2014.

- ^ Gómez-Galisteo, M. Carmen (2011). The Wind Is Never Gone: Sequels, Parodies and Rewritings of Gone with the Wind. McFarland & Company. p. 173. ISBN 978-0-7864-5927-8.

- ^ "The Scarlett O'Hara War (1980)". Allmovie. Rovi Corporation. Retrieved March 2, 2013.

- ^ Spencer, Charles (October 8, 2007). "Moonlight and Magnolias: Comedy captures the birth of a movie classic". The Daily Telegraph. Retrieved January 17, 2013.

- ^ Thames, Stephanie. "The Making Of A Legend: Gone With The Wind (1988) – Articles". TCM database. Turner Classic Movies. Retrieved March 2, 2013.

- ^ McAllister, Bill (March 5, 1990). "Postal Service Goes Hollywood, Puts Legendary Stars on Stamp". The Daily Gazette. p. B9.

- ^ "Scarlett (1994)". Allmovie. Rovi Corporation. Retrieved March 3, 2013.

Further reading

- Bridges, Herb (1999). Gone with the Wind: The Three-Day Premiere in Atlanta. Mercer University Press. ISBN 978-0-86554-672-1.

- Cameron, Judy; Christman, Paul J (1989). The Art of Gone with the Wind: The Making of a Legend. Prentice Hall. ISBN 978-0-13-046740-9.

- Harmetz, Aljean (1996). On the Road to Tara: The Making of Gone with the Wind. New York: Harry N. Abrams. ISBN 978-0-8109-3684-3.

- Lambert, Gavin (1973). GWTW: The Making of Gone With the Wind. New York: Little, Brown and Company. ISBN 978-0-316-51284-8.

- Vertrees, Alan David (1997). Selznick's Vision: Gone with the Wind and Hollywood Filmmaking. University of Texas Press. ISBN 978-0-292-78729-2.

External links

- Gone with the Wind at IMDb

- Gone with the Wind at the TCM Movie Database

- Template:External link

- Template:External link and Template:External link premiere films at the Atlanta History Center.

- Template:External link

- Template:External link

- Template:External link

- Gone with the Wind at Rotten Tomatoes

- 1939 films

- Gone with the Wind

- Margaret Mitchell

- 1930s historical films

- 1930s romance films

- 1930s romantic drama films

- American films

- American Civil War films

- American epic films

- American romantic drama films

- Best Picture Academy Award winners

- Culture of Atlanta, Georgia

- English-language films

- Film scores by Max Steiner

- Films about American slavery

- Films about rape

- Films about revenge

- Films based on American novels

- Films directed by Victor Fleming

- Films featuring a Best Actress Academy Award-winning performance

- Films featuring a Best Supporting Actress Academy Award winning performance

- Films produced by David O. Selznick

- Films set in Georgia (U.S. state)

- Films set in Atlanta, Georgia

- Films set in London

- Films set in the 1860s

- Films set in the 19th century

- Films shot in California

- Films whose art director won the Best Art Direction Academy Award

- Films whose cinematographer won the Best Cinematography Academy Award

- Films whose director won the Best Directing Academy Award

- Films whose editor won the Best Film Editing Academy Award