Goths

The Goths (Template:Lang-got; Template:Lang-non; Template:Lang-la; Template:Lang-gr) were an East Germanic people, two of whose branches, the Visigoths and the Ostrogoths, played an important role in the fall of the Western Roman Empire and the emergence of Medieval Europe.

An important source of knowledge of the Goths is Getica, a semi-fictional account, written in the 6th century by the Roman historian Jordanes, of their migration from southern Scandza (Scandinavia), into Gothiscandza—believed to be the lower Vistula region in modern Pomerania—and from there to the coast of the Black Sea. Archaeological evidence from the Pomeranian Wielbark culture and the Chernyakhov culture, northeast of the lower Danube, confirms that some such migration did in fact take place. In the 3rd century, the Goths crossed either the lower Danube or the Black Sea, ravaged the Balkans and Anatolia as far as Cyprus, and sacked Athens, Byzantium, and Sparta.[1] By the 4th century, the Goths had captured Dacia,[2][3] and were divided into at least two distinct groups separated by the Dniester River, the Thervingi (led by the Balti dynasty) and the Greuthungi (led by the Amali dynasty).

The Goths dominated a vast area,[4] which at its peak under the King Ermanaric and his sub-king Athanaric possibly extended all the way from the Danube to the Ural Mountains, and from the Black to the Baltic Sea.[5][6] In the late 4th century, the Huns came from the east and invaded the region controlled by the Goths. Although the Huns successfully subdued many of the Goths, who joined their ranks, a group of Goths led by Fritigern fled across the Danube. They then revolted against the Roman Empire, winning a decisive victory at the Battle of Adrianople. By this time the Gothic missionary Wulfila, who devised the Gothic alphabet to translate the Bible, had converted many of the Goths from paganism to Arian Christianity. In the 4th, 5th, and 6th centuries the Goths separated into two main branches, the Visigoths, who became federates of the Romans, and the Ostrogoths, who joined the Huns.

After the Ostrogoths successfully revolted against the Huns at the Battle of Nedao in 454, their leader Theodoric the Great settled his people in Italy, founding a kingdom which eventually gained control of the whole peninsula. Shortly after Theodoric's death in 526, the country was captured by the Byzantine Empire, in a war that devastated and depopulated the peninsula.[7] After their able leader Totila was killed at the Battle of Taginae, effective Ostrogothic resistance ended, and the remaining Goths were assimilated by the Lombards, another Germanic tribe, who invaded Italy and founded a kingdom in the northern part of the country in 567 AD.

The Visigoths sacked Rome under Alaric I in 410, defeated Attila at the Battle of the Catalaunian Plains under Theodoric I in 451, and founded a kingdom in Aquitaine. The Visigoths were pushed to Hispania by the Franks following the Battle of Vouillé in 507. By the late 6th century, the Visigoths had converted to Catholicism. They were conquered in the early 8th century by the Muslim Moors, but began to regain control under the leadership of the Visigothic nobleman Pelagius, whose victory at the Battle of Covadonga began the centuries-long Reconquista. The Visigoths founded the Kingdom of Asturias, which eventually evolved into modern Spain and Portugal.[8]

Gothic language and culture largely disappeared during the Middle Ages, although its influence continued to be felt in small ways in some western European states. As late as the 16th century a small number of people in the Crimea may still have been speaking the Gothic language known as Crimean Gothic.[9]

Etymology

The Goths have been referred to by many names, perhaps at least in part because they comprised many separate ethnic groups, but also because in early accounts of Proto-Indo-European and later Germanic migrations in general it was common practice to use various names to refer to the same group. The Goths clearly believed (as most modern scholars do)[10] that the various names all derived from a single prehistoric ethnonym that referred originally to a uniform culture that flourished around the middle of the first millennium BC—the original "Goths".

The word "Goths" derives from the stem Gutan-.[11] This stem produces the singular *Gutô, plural *Gutaniz in Proto-Germanic. It survives in the modern Scandinavian tribal name Gutes, which is what the inhabitants of present-day Swedish island Gotland in Baltic Sea call themselves. (In Gutnish - Gutar, in Swedish "Gotlänningar") Another modern Scandinavian tribal name, Geats (in Swedish "Götar"), which is what the (original) inhabitants of present-day Götaland/Geatland (originally south of Svealand, and north of the former Danish regions Skåne and Halland) call themselves, derives from a related Proto-Germanic word, *Gautaz (plural *Gautôz). (Both *Gautaz and *Gutô relate to the Proto-Germanic verb *geutaną, meaning "to pour".[12]

The Indo-European root of the word "geutan" and its cognates in other language is *gʰewd-[13] American Heritage Dictionary (AHD) designates *gʰewd- as a centum form, in reliance on Julius Pokorny.[14] This same root may be connected to the name of a river that flows through Västergötland in Sweden, the Göta älv, which drains Lake Vänern into the Kattegat[15] at the city of Gothenburg (Swedish: Göteborg), on the western coast of Sweden. It is certainly plausible that a flowing river would be given a name that describes it as "pouring", and that, if the original home of the Goths was near that river, they would choose an ethnonym that described them as living by the river. Another possibility is of course that the name of the "Geats" developed independently from that of the Gutar/Goths. The earliest mention of Geats was possibly made by Ptolemy in the 100's AD ("doutai" or "goutai") and in the 500's by Jordanes ("gauthigoth") and Prokopios ("gautoi")[16]

Both the Goths and the Gutes were called Gotar in Old West Norse, and Gutar in Old East Norse (for example in the Gutasaga and in runic inscription on the Rökstone). In contrast, the other tribe, the Geats, were clearly differentiated from the Goths / Gutes. Since Old Norse literature do not distinguish between the Goths and the Gutes (Gotlanders), but do clearly distinguish between the Goths or Gutes on the one hand, and the Geats on the other (as do Old English literature), it is plausible that the Goths who migrated out of Scandinavia were members of the Gutes tribe.

At some time in European prehistory, consonant changes according to Grimm's Law shifted *gʰ to *g and *d to *t in Germanic. This same law more or less rules out *gʰedʰ-,[17] which would become *ged- in Germanic.

According to the rules of Indo-European ablaut, the full grade (containing an *e), *gʰewd-, might be replaced with the zero-grade (the *e disappears), *gʰud-, or the o-grade (the *e changes to an *o), *gʰowd-, accounting for the various forms of the name. The zero-grade is preserved in modern times in the Lithuanian ethnonym for Belarusians, Gudai (earlier Baltic Prussian territory before Slavic conquests by about 1200 CE), and in certain Prussian towns in the territory around the Vistula River in Gothiscandza, today Poland (Gdynia, Gdańsk)[dubious – discuss]. The use of all three grades suggests that the name derives from an Indo-European stage; otherwise, it would be from a line descending from one grade. However, when and where the ancestors of the Goths assigned this name to themselves and whether they used it in Indo-European or proto-Germanic times remain unsolved questions of historical linguistics and prehistoric archaeology.

A compound name, Gut-þiuda, at root the "Gothic people", appears in the Gothic Calendar (aikklesjons fullaizos ana gutþiudai gabrannidai). Parallel occurrences indicate that it may mean "country of the Goths": Old Icelandic Sui-þjòd, "Sweden"; Old English Angel-þēod, "Anglia"; Old Irish Cruithen-tuath, "country of the Picts".[11]

History

Origins

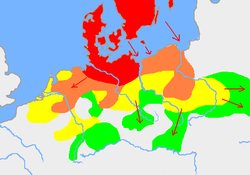

red: Oksywie culture,

then early Wielbark culture

blue: Jastorf culture (light: expansion, purple: repressed)

yellow: Przeworsk culture (orange: repressed)

pink, orange, purple: expansion of Wielbark culture (2nd century AD)

According to Jordanes' Getica, written in the mid-6th century, the earliest migrating Goths sailed from Scandza (Scandinavia) under King Berig[20] in three ships[21] and named the place at which they landed after themselves: "Today [says Jordanes] it is called Gothiscandza" ("Scandza of the Goths").[22] Although the exact location of Gothiscandza is unclear, Jordanes tells us that one shipload "dwelled in the province of Spesis on an island surrounded by the shallow waters of the Vistula."[23] From there, the Goths then moved into an area along the southern coast of the Baltic Sea which was inhabited by the "Ulmerugi" (Rugii), expelled them,[24] and also subdued the neighboring Vandals.

The Goths, according to Isidore of Seville, were descended from Gog and Magog, and of the same race as the Getae.[25][26]

According to Tacitus, the Goths and the neighboring Rugii and Lemovii carried round shields and short swords, and obeyed their regular authority.[24][27][28]

Pliny[29] recounts a report of Pytheas, an explorer who visited Northern Europe in the 4th century BC., that the "Gutones, a people of Germany," inhabit the shores of an estuary of at least 6,000 stadia called Mentonomon (i.e., the Baltic Sea), where amber is cast up by the waves. Lehmann (cited in the section on Etymology, above) accepts this, although one version of Pliny's manuscript uses the word "Guiones" instead of "Gutones."[30] In Pliny's only other mention of the Gutones,[31] he states that the Vandals are one of the five races of Germany, and that the Vandals comprise four distinct groups, the Burgodiones, the Varinnae, the Charini and the Gutones. He does not specify where the Vandals lived, but his description is consistent with his contemporary Ptolemy's description of the east Germanic tribes.[32] Since we have only Pliny's report of what Pytheas said about the Gutones, and not Pytheas's report itself, the 4th century BC date is unconfirmed, but not necessarily invalid.

The earliest known material culture associated with the Goths on the southern coast of the Baltic Sea is the Wielbark culture,[33] centered on the modern region of Pomerania in northern Poland. This culture replaced the local Oksywie or Oxhöft culture in the 1st century, when a Scandinavian settlement was established in a buffer zone between the Oksywie culture and the Przeworsk culture.[34]

The culture of this area was influenced by southern Scandinavian culture beginning as early as the late Nordic Bronze Age and early Pre-Roman Iron Age (c. 1300 – c. 300 BC).[35] In fact, the Scandinavian influence on Pomerania and today's northern Poland from c. 1300 BC (period III) and onwards was so considerable that some see the culture of the region as part of the Nordic Bronze Age culture.[36]

The Goths are believed to have crossed the Baltic Sea sometime between the end of this period (ca 300 BC) and AD 100. Early archaeological evidence in the traditional Swedish province of Östergötland suggests a general depopulation during this period.[37] However, this is not confirmed in more recent publications.[38] The settlement in today's Poland may correspond to the introduction of Scandinavian burial traditions, such as the stone circles and the stelae especially common on the island of Gotland and other parts of southern Sweden.

However, Heather is skeptical of this hypothesis, claiming that there is no archaeological evidence for a substantial emigration from Scandinavia.[39]

Migration to the Black Sea

The arrival of Germanic-speaking invaders along the coast of the Black Sea is generally explained as a gradual migration of the Goths from what is now Poland to Ukraine, reflecting the tradition of Jordanes and old songs.[40] According to Jordanes's Getica, the Goths entered Oium, part of Scythia,[41] under their 5th king, Filimer, where they subdued the Spali (Sarmatians).[42] There they became divided into the Thervingi (later known as Visigoths) ruled by the Balthi family and the Greuthungi (Ostrogoths) ruled by the Amali family.[43] Jordanes parses Ostrogoths as "eastern Goths", and Visigoths as "Goths of the western country."[44]

Beginning in the middle 2nd century, the Wielbark culture shifted to the southeast, towards the Black Sea. The part of the Wielbark culture that moved was the oldest portion, located west of the Vistula and still practicing Scandinavian burial traditions.[45] It has been suggested that the Goths maintained contact with southern Sweden during their migration.[46]

In Ukraine, they installed themselves as the rulers of the local Zarubintsy culture, forming the new Chernyakhov culture (c. 200 – c. 400). Chernyakhov settlements tend to cluster in open ground in river valleys. The houses include sunken-floored dwellings, surface dwellings, and stall-houses. The largest known settlement (Budesty-Budești) is 35 hectares.[47] Most settlements are open and unfortified, although some forts have also been discovered.[citation needed] Chernyakhov cemeteries feature both cremation and inhumation burials; among the latter the head is to the north. Some graves were left empty. Grave goods often include pottery, bone combs, and iron tools, but hardly ever weapons.[48]

Around the mid 2nd century AD, there was a significant migration by Germanic tribes of Scandinavian origin (Rugii, Goths, Gepidae, Vandals, Burgundians, and others)[49] towards the south-east, creating turmoil along the entire Roman frontier.[49][50][51][52] The 6th century Byzantine historian Procopius noted that the Goths, Gepidae and Vandals were physically and culturally identical, suggesting a common origin.[53] These migrations culminated in the Marcomannic Wars, which resulted in widespread destruction and the first invasion of Italy in the Roman Empire period.[52]

The Goths in Scythia and Dacia

Upon their arrival on the Pontic Steppe, the Goths quickly adopted the ways of the steppe nomads,[54] excelling in horsemanship, archery and falconry.[55] In addition they were also accomplished agriculturalists[56] and seafarers.[57] J. B. Bury describes the Gothic period as "the only non-nomadic episode in the history of the steppe."[58] Encyclopedia Britannica compares the migration of the Goths to that of the early Mongols, who migrated southward from the forests and came to dominate the eastern Eurasian steppe around the same time as the Goths in the west.[59]

The first Greek references to the Goths call them Scythians, since this area along the Black Sea historically had been occupied by an unrelated people of that name. The term as applied to the Goths appears to be geographical rather than ethnological in reference.[60]

In the first attested incursion in Thrace the Goths were mentioned as Boranoi by Zosimus, and then as Boradoi by Gregory Thaumaturgus.[61] The first incursion of the Roman Empire that can be attributed to Goths is the sack of Histria in 238. Several such raids followed in subsequent decades,[62] in particular the Battle of Abrittus in 251, led by Cniva, in which the Roman Emperor Decius was killed. At the time, there were at least two groups of Goths: the Thervingi and the Greuthungi. Goths were subsequently heavily recruited into the Roman Army to fight in the Roman-Persian Wars, notably participating at the Battle of Misiche in 242.

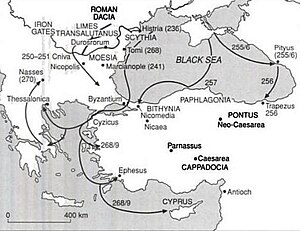

The first seaborne raids took place in three subsequent years, probably 255-257. An unsuccessful attack on Pityus was followed in the second year by another which sacked by Pityus and Trapezus and ravaged large area in the Pontus. In the third year a much larger force devastated large areas of Bithynia and the Propontis, including the cities of Chalcedon, Nicomedia, Nicaea, Apamea, Cius and Prusa. By the end of the raids the Goths had seized control over Crimea (Kingdom of the Bosporus) and the Bosphorus and captured several cities on the Euxinean coast, including Olbia and Tyras, which enabled them to engage in widespread naval activities.[63]

After a 10-year gap, the Goths, along with the Heruli, another Germanic tribe from Scandinavia, raiding on 500 ships,[64] sacked Heraclea Pontica, Cyzicus and Byzantium. They were defeated by the Roman navy but managed to escape into the Aegean Sea, where they ravaged the islands of Lemnos and Scyros, broke through Thermopylae and sacked several cities of southern Greece (province of Achaea) including Athens, Corinth, Argos, Olympia and Sparta.[65]

Then an Athenian militia, led by the historian Dexippus, pushed the invaders to the north where they were intercepted by the Roman army under Gallienus.[66] He won an important victory near the Nessos (Nestos) river, on the boundary between Macedonia and Thrace, the Dalmatian cavalry of the Roman army earning a reputation as good fighters. Reported barbarian casualties were 3,000 men.[67] Subsequently, the Heruli leader Naulobatus came to terms with the Romans.[64]

After Gallienus was assassinated outside Milan in the summer of 268 in a plot led by high officers in his army, Claudius was proclaimed emperor and headed to Rome to establish his rule. Claudius' immediate concerns were with the Alamanni, who had invaded Raetia and Italy. After he defeated them in the Battle of Lake Benacus, he was finally able to take care of the invasions in the Balkan provinces.[68]

In the meantime, the second and larger sea-borne invasion had started. An enormous coalition consisting of Goths (Greuthungi and Thervingi), Gepids and Peucini, led again by the Heruli, assembled at the mouth of river Tyras (Dniester).[69] The Augustan History and Zosimus claim a total number of 2,000–6,000 ships and 325,000 men.[70] This is probably a gross exaggeration but remains indicative of the scale of the invasion. After failing to storm some towns on the coasts of the western Black Sea and the Danube (Tomi, Marcianopolis), the invaders attacked Byzantium and Chrysopolis. Part of their fleet was wrecked, either because of the Gothic inexperience in sailing through the violent currents of the Propontis[71] or because it was defeated by the Roman navy.

Then they entered the Aegean Sea and a detachment ravaged the Aegean islands as far as Crete, Rhodes and Cyprus. The fleet probably also sacked Troy and Ephesus, destroying the Temple of Artemis, one of the Seven Wonders of the Ancient World. While their main force had constructed siege works and was close to taking the cities of Thessalonica and Cassandreia, it retreated to the Balkan interior at the news that the emperor was advancing. On their way, they plundered Doberus (Paionia ?) and Pelagonia.[72]

Learning of the approach of Claudius, the Goths first attempt to directly invade Italy.[73] They are engaged near Naissus by a Roman army led by Claudius advancing from the north. The battle most likely took place in 269, and was fiercely contested. Large numbers on both sides were killed but, at the critical point, the Romans tricked the Goths into an ambush by pretended flight. Some 50,000 Goths were allegedly killed or taken captive and their base at Thessalonika destroyed.[67]

It seems that Aurelian who was in charge of all Roman cavalry during Claudius' reign, led the decisive attack in the battle. Some survivors were resettled within the empire, while others were incorporated into the Roman army. The battle ensured the survival of the Roman Empire for another two centuries. In 270, after the death of Claudius, Goths under the leadership of Cannabaudes again launched an invasion on the Roman Empire, but were defeated by Aurelian, who however surrendered Dacia beyond the Danube.

Around 275 the Goths launched a last major assault on Asia Minor, where piracy by Black Sea Goths was causing great trouble in Colchis, Pontus, Cappadocia, Galatia and even Cilicia.[74] They were defeated sometime in 276 by Emperor Marcus Claudius Tacitus.[74]

In 332 Constantine helped the Sarmatians to settle on the north banks of the Danube to defend against the Goths' attacks and thereby enforce the Roman Empire's border. Around 100,000 Goths were reportedly killed in battle, and Ariaricus, son of the King of the Goths, was captured. In 334, Constantine evacuated approximately 300,000 Sarmatians from the north bank of the Danube after a revolt of the Sarmatians' slaves. From 335 to 336, Constantine, continuing his Danube campaign, defeated many Gothic tribes.[75][76][77]

Both the Greuthungi and Thervingi became heavily Romanized during the 4th century. This came about through trade with the Romans, as well as through Gothic membership of a military covenant, which was based in Byzantium and involved pledges of military assistance. Reportedly, 40,000 Goths were brought by Constantine to defend Constantinople in his later reign, and the Palace Guard was mostly composed of Germanic soldiers, as the quality and quantity of the native Romans troops kept declining.[78] The Goths were converted to Arianism by Ulfila during this time.

Refugees and invaders in the Roman Empire

In the 4th century, the Greuthungian king Ermanaric became the most powerful Gothic ruler, coming to dominate a vast area of the Pontic Steppe which possibly stretched from the Baltic Sea to the Black Sea as far eastwards as the Ural Mountains.[6] Ermanaric's dominance of the Volga-Don trade routes made historian Gottfried Schramm consider his realm as a forerunner of the Viking founded state of Kievan Rus'.[79]

Hunnic domination of the Gothic kingdoms in Scythia began in the 370s according to Ammianus.[80] and confirmed by the Eunapius and the later Zosimus. Major sources for this period of Gothic history include Ammianus Marcellinus' Res gestae, which mentions Gothic involvement in the civil war between emperors Procopius and Valens of 365 and recounts the Gothic refugee crisis and revolt of 376–82. Around 375 AD the Huns overran the Alans and then the Goths. It is possible that the Hunnic attack came as a response to the Gothic eastwards expansion.[81][82][83]

Christopher I. Beckwith suggests that the entire Hunnic thrust into Europe and the Roman Empire was an attempt to subdue independent Goths in the west.[83] Ermanaric committed suicide, and the Greuthungi fell under Hunnic dominance. Shortly afterwards, the Huns fell upon the Thervingi, whose staunchly pagan ruler Athanaric sought refuge in the mountains. Meanwhile, the Arian Thervingian rebel chieftain Fritigern approached the Eastern Roman Emperor Valens in 376 with a portion of his people and asked to be allowed to settle with his people on the south bank of the Danube. Valens permitted this, and even assisted the Goths in their crossing of the river[84] (probably at the fortress of Durostorum).

Following a famine the Gothic War of 376–82 ensued, and the Goths and some of the local Thracians rebelled. The Roman Emperor Valens was killed at the Battle of Adrianople in 378. Following the decisive Gothic victory at Adrianople, Julius, the magister militum Eastern Roman Empire,[85] organized a widescale massacre of Goths in Asia Minor, Syria and other parts of the Roman East.[86] Fearing rebellion, Julian lured the Goths into the confines of urban streets from which they could not escape, massacring both soldiers and civilians alike.[86] As word spread among the Goths rioted throughout the region, and large numbers were killed.[86] Kulikowski suggests that survivors of the massacre settled in Phrygia.[87]

The Goths remained divided — as Visigoths and Ostrogoths — during the 5th century. These two tribes were among the Germanic peoples who clashed with the late Roman Empire during the Migration Period. A Visigothic force led by Alaric I sacked Rome in 410. Honorius granted the Visigoths Aquitania, where they defeated the Vandals and conquered most of the Iberian Peninsula by 475.

In the meantime, under Theodemir, the Ostrogoths broke away from Hunnic rule following the Battle of Nedao in 454, and decisively defeated the Huns again under Valamir at Bassianae in 468. At the request of emperor Zeno, Theodoric the Great conquered all of Italy from the Scirian Odoacer beginning in 488. The Goths were briefly reunited under one crown in the early 6th century under Theodoric the Great, who became regent of the Visigothic kingdom following the death of Alaric II at the Battle of Vouillé in 507. Procopius interpreted the name Visigoth as "western Goths" and the name Ostrogoth as "eastern Goth", reflecting the geographic distribution of the Gothic realms at that time.

The Ostrogothic kingdom persisted until 553 under Teia, when Italy returned briefly to Byzantine control. This restoration of imperial rule was reversed by the conquest of the Lombards in 568. This period of Ostrogothic history is documented by Procopius' de bello gothico, which describes the Gothic war of 535–52. The Visigothic kingdom lasted until 711 under Roderic, when it fell to the Muslim Umayyad invasion of the Iberian Peninsula (Al-Andalus).

Some Visigothic nobles under the leadership of Pelagius of Asturias did manage to defeat the Moors at the Battle of Covadonga, and subsequently established the Kingdom of Asturias in the northwest of Iberian Peninsula. The Gothic victory at Covadonga is regarded as the initiation of the Reconquista, and it was from the Asturian kingdom that modern Spain evolved. These Goths became completely hispanisized, little left of their original culture except for Germanic names still in use in present-day Spain.

In the late 6th century Goths settled as foederati in parts of Asia Minor. Their descendants, who formed the elite Optimatoi regiment, still lived there in the early 8th century. While they were largely assimilated, their Gothic origin was still well-known: the chronicler Theophanes the Confessor calls them Gothograeci.

Physical appearance

The 6th-century Byzantine historian Procopius wrote that the Goths were tall and blond haired:

For they all have white bodies and fair hair, and are tall and handsome to look upon...[53]

The 4th century Greek historian Eunapius described the Goths' powerful build in a pejorative way:

Their bodies provoked contempt in all who saw them, for they were far too big and far too heavy for their feet to carry them, and they were pinched in at the waist — just like those insects Aristotle writes of.[88]

As the Goths increasingly became soldiers in the Roman armies in the 4th century AD, contributing to the almost complete Germanization of the Roman Army by that time,[49] the Gothic penchant for wearing skins became fashion in Constantinople, which was heavily denounced by conservatives.[89] The 4th century Greek bishop Synesius compared the Goths to wolves among sheep, mocked them for wearing skins and questioned their loyalty towards Rome:

A man in skins leading warriors who wear the chlamys, exchanging his sheepskins for the toga to debate with Roman magistrates and perhaps even sit next to a consul, while law-abiding men sit behind. Then these same men, once they have gone a little way from the senate house, put on their sheepskins again, and when they have rejoined their fellows they mock the toga, saying that they cannot comfortably draw their swords in it.[89]

Culture

Art

Before the invasion of the Huns the Gothic Chernyakhov culture produced jewelry, vessels, and decorative objects in a style much influenced by Greek and Roman craftsmen. They developed a polychrome style of gold work, using wrought cells or setting to encrust gems into their gold objects. This style was influential in West Germanic areas well into the Middle Ages.

Language

The Gothic language is an extinct Germanic language that was spoken by the Goths. It is known primarily from the Codex Argenteus, a 6th-century copy of a 4th-century Bible translation, and is the only East Germanic language with a sizable corpus. All others, including Burgundian and Vandalic, are known, if at all, only from proper names that survived in historical accounts, and from loan-words in other languages like Spanish and French.

As a Germanic language, Gothic is a part of the Indo-European language family. It is the Germanic language with the earliest attestation but has no modern descendants. The oldest documents in Gothic date back to the 4th century. The language was in decline by the mid-6th century, due in part to the military defeat of the Goths at the hands of the Franks, the elimination of the Goths in Italy, and geographic isolation (in Spain the Gothic language lost its last and probably already declining function as a church language when the Visigoths converted to Catholicism in 589).[90]

The language survived as a domestic language in the Iberian peninsula (modern Spain and Portugal) as late as the 8th century, and Frankish author Walafrid Strabo wrote that it was still spoken in the lower Danube area and in isolated mountain regions in Crimea in the early 9th century (see Crimean Gothic). Gothic-seeming terms found in later (post-9th century) manuscripts may not belong to the same language.

The existence of such early attested corpora makes it a language of considerable interest in comparative linguistics.

Economy

Roman writers note that the Goths neither claimed taxes from their own nor their subjects. The early 5th century Christian writer Salvian compared the Goths' and related people's favourable treatment of the poor to the miserable state of peasants in Roman Gaul:

For in the Gothic country the barbarians are so far from tolerating this sort of oppression that not even Romans who live among them have to bear it. Hence all the Romans in that region have but one desire, that they may never have to return to the Roman jurisdiction. It is the unanimous prayer of the Roman people in that district that they may be permitted to continue to lead their present life among the barbarians.[91]

Religion

Initially pagan, the Goths were gradually converted to Arian Christianity in the course of the 4th century as a result of the missionary activity by the Gothic bishop Wulfila, who devised an alphabet to translate the Bible.

During the 370s, converted Goths were persecuted by the remaining pagan authorities of the Thervingi people.

The Visigothic Kingdom in Hispania was converted to Catholicism in the 7th century.

The Ostrogoths (and their remnants, the Crimean Goths) were in close connection to the Patriarchate of Constantinople from the 5th century, and became fully incorporated under the Metropolitanate of Gothia from the 9th century.

Legacy

The Gutes (Gotlanders) themselves had oral traditions of a mass migration towards southern Europe, recorded in the Gutasaga. If the facts are related, this would be a unique case of a tradition that endured for more than a thousand years and that actually pre-dates most of the major splits in the Germanic language family.

The Goths' relationship with Sweden became an important part of Swedish nationalism, and until the 19th century the Swedes were commonly considered to be the direct descendants of the Goths. Today, Swedish scholars identify this as a cultural movement called Gothicismus, which included an enthusiasm for things Old Norse.

In Medieval and Modern Spain, the Visigoths were believed to be the origin of the Spanish nobility (compare Gobineau for a similar French idea). By the early 7th century, the ethnic distinction between Visigoths and Hispano-Romans had all but disappeared, but recognition of a Gothic origin, e.g. on gravestones, still survived among the nobility. The 7th-century Visigothic aristocracy saw itself as bearers of a particular Gothic consciousness and as guardians of old traditions such as Germanic namegiving; probably these traditions were on the whole restricted to the family sphere (Hispano-Roman nobles did service for Visigothic nobles already in the 5th century and the two branches of Spanish aristocracy had fully adopted similar customs two centuries later).[92]

In Spain, a man acting with arrogance would be said to be "haciéndose los godos" ("making himself to act like the Goths"). Thus, in Chile, Argentina and the Canary Islands, godo was an ethnic slur used against European Spaniards, who in the early colony period often felt superior to the people born locally (criollos). In Colombia the members of the Conservative Party were referred to as godos.

The Spanish and Swedish claims of Gothic origins led to a clash at the Council of Basel in 1434. Before the assembled cardinals and delegations could engage in theological discussion, they had to decide how to sit during the proceedings. The delegations from the more prominent nations argued that they should sit closest to the Pope, and there were also disputes over who was to have the finest chairs and who was to have their chairs on mats. In some cases, they compromised so that some would have half a chair leg on the rim of a mat. In this conflict, Nicolaus Ragvaldi, bishop of Växjö, claimed that the Swedes were the descendants of the great Goths, and that the people of Västergötland (Westrogothia in Latin) were the Visigoths and the people of Östergötland (Ostrogothia in Latin) were the Ostrogoths. The Spanish delegation retorted that it was only the lazy and unenterprising Goths who had remained in Sweden, whereas the heroic Goths had left Sweden, invaded the Roman empire and settled in Spain.[93][94]

Written sources about the Goths

- Ambrose: The prologue of De Spiritu Sancto (On the Holy Ghost) makes passing reference to Athanaric's royal titles before 376.[95][citation needed] Comment on Saint Luke: "Chuni in Halanos, Halani in Gothos, Gothi in Taifalos et Sarmatas insurexerunt"[improper synthesis?]

- Ammianus Marcellinus: Res Gestae Libri XXXI.[96]

- Aurelius Victor: The Caesars, a history from Augustus to Constantius II

- Basil of Caesarea: Letters

- Cassiodorus: A lost history of the Goths used by Jordanes

- Claudian: Poems

- Dexippus: Scythica which was used by Zosimus for his New hystory

- Epitome de Caesaribus

- Eunapius of Sardis: Live of the Sophists

- Eutropius: Breviary

- Gregory Thaumaturgus: Canonical letter

- Gregory of Nyssa

- Historia Augusta: A history from Hadrian to Carus. However, large portions are known to be fraudulent and the factual accuracy of the remainder is disputed.[97]

- Jerome: Chronicle

- Jordanes

- Julian the Apostate

- Lactantius: On the death of the Persecutors

- Olympiodorus of Thebes

- Orosius: History against pagans

- Panegyrici latini

- Paulinus: Life of bishop Ambrose of Milan

- Philostorgius: Greek church history

- Sozomen

- Synesius: De regno and De providentia

- Tacitus: Germania, chapters 17, 44

- Themistius: Speeches

- Theoderet of Cyrrhus

- Theodosian Code

- Zosimus

See also

References

Citations

- ^ Gibbon, Edward (1930). The Decline and Fall of the Roman Empire. Plain Label Books. ISBN 978-1-60303-405-0.

- ^ "Goth". Encyclopædia Britannica Online. Encyclopædia Britannica, Inc. Retrieved 16 January 2015.

- ^ "Visigoth". Encyclopædia Britannica Online. Encyclopædia Britannica, Inc. Retrieved 16 January 2015.

- ^ "Ostrogoth". Encyclopædia Britannica Online. Encyclopædia Britannica, Inc. Retrieved 16 January 2015.

- ^ Waldman & Mason 2006, p. 575

- ^ a b Wolfram 1997, pp. 26–28 harvnb error: multiple targets (2×): CITEREFWolfram1997 (help)

- ^ London, Jack (2007). The Human Drift. 1st World Publishing. p. 11. ISBN 978-1-4218-3371-2.

- ^ "Spain: The Christian states, 711–1035". Encyclopædia Britannica Online. Encyclopædia Britannica, Inc. Retrieved 16 January 2015.

- ^ Bennett, William H (1980). An Introduction to the Gothic Language. p. 27..

- ^ Wolfram 1990, pp. 16–35

- ^ a b Lehmann, Winfred P.; Helen-Jo J. Hewitt (1986). A Gothic Etymological Dictionary. Leiden: E.J. Brill. p. 164. ISBN 978-90-04-08176-5., as is apparent from Pytheas's name for them, the Gutones, cited in Pliny'.

- ^ (Compare modern Swedish gjuta (pour, perfuse, found), modern Dutch gieten, modern German gießen, Gothic giutan, old Scandinavian giota, old English geotan all cognate with Latin fondere "to pour" and old Greek cheo "I pour".

- ^ Roots, Bartleby, p. 165.

- ^ The American Heritage Dictionary of the English Language, p. 447.

- ^ Wolfram 1990, p. 21

- ^ NE (Nationalencyklopedin), (2014). "götar". Nationalencyklopedin. Retrieved 6 January 2014.

{{cite web}}:|first=has numeric name (help) - ^ Roots, Bartleby, p. 155.

- ^ Kinder, Hermann (1988), Penguin Atlas of World History, vol. I, London: Penguin, p. 108, ISBN 0-14-051054-0.

- ^ "Languages of the World: Germanic languages". The New Encyclopædia Britannica. Chicago, IL, United States: Encyclopædia Britannica, Inc. 1993. ISBN 0-85229-571-5.

- ^ Jordanes; Charles C. Mierow, Translator (1997). "The Origins and Deeds of the Goths". Calgary: J. Vanderspoel, Department of Greek, Latin and Ancient History, University of Calgary. p. 25. Retrieved 26 October 2013.

{{cite web}}:|author2=has generic name (help) - ^ Jordanes, p. 94.

- ^ Jordanes. p. 26.

- ^ Jordanes. p. 96.

- ^ a b Beck, Heinrich; Geuenich, Dieter; Hoops, Johannes; Jankuhn, Herbert; Steuer, Heiko (2004), Reallexikon der Germanischen Altertumskunde (in German) (2nd ed.), Berlin: Walter de Gruyter, pp. 452ff, ISBN 978-3-11-017733-6.

- ^ "History of the Goths: Historia de regibus Gothorum, Wandalorum et Suevorum". History of the Goths by Isidore of Seville.

goths descended from Gog and Magog

- ^ Isidore (Bishop of Seville.). History of the Kings of the Goths, Vandals, and Suevi. E.J. Brill.

- ^ The Works of Tacitus: the Oxford Translation, Revised, with Notes, BiblioBazaar, 2008, p. 836, 0559473354.

- ^ Rives, JB (1999), On Tacitus, Germania, Oxford University Press, p. 311, ISBN 0-19-815050-4.

- ^ the Elder, Pliny, "11", Natural History, vol. 37

- ^ Tacitus, Cornelius; JB Rives, translator and commentator (1999), Germania, Oxford: Oxford University Press, p. 113, ISBN 0-19-924000-0

{{citation}}:|author2=has generic name (help).Since Pytheas mentions the Teutones in the same passage, it securely dates them to 300 BC. - ^ the Elder, Pliny, "13", Natural History, vol. 4.

- ^ Ptolomy, "10", Geography, vol. II.

- ^ The Goths in Greater Poland, Poznan.

- ^ Kokowski, Andrzej (1999), Archäologie der Goten (in German), ISBN 83-907341-8-4.

- ^ Gothic Connections, Institutionen för arkeologi och antik historia – Uppsala universitet.

- ^ Dabrowski, J. (1989). Nordische Kreis un Kulturen Polnischer Gebiete. Die Bronzezeit im Ostseegebiet. p. 73.

- ^ Oxenstierna (1945), Die Urheimat der Goten.

- ^ Kaliff (2001), Gothic Connections: Contacts between Eastern Scandinavia and the Southern Baltic Coast, 1000 BC – 500 A.

- ^ Heather, The Goths, p. 26.

- ^ Wolfram 1990, p. 42

- ^ Jordanes. p. 27.

- ^ Jordanes. p. 28.

- ^ Jordanes. p. 42.

- ^ Jordanes. p. 82.

- ^ Jewellery of the Goths, Poznan: Muzarp.

- ^ Arhenius, B, Connections between Scandinavia and the East Roman Empire in the Migration Period, pp. 119, 134, in Alcock, Leslie (1990), From the Baltic to the Black Sea: Studies in Medieval Archaeology, London: Unwin Hyman, pp. 118–37.

- ^ Heather, Peter; Matthews, John (1991), The Goths in the Fourth Century, Liverpool: Liverpool University Press, pp. 52–4.

- ^ Heather, Peter; Matthews, John (1991), Goths in the Fourth Century, Liverpool: Liverpool University Press, pp. 54–6.

- ^ a b c "History of Europe: The Germans and Huns". Encyclopædia Britannica Online. Encyclopædia Britannica, Inc. Retrieved 16 January 2015.

- ^ "Ancient Rome: The barbarian invasions". Encyclopædia Britannica Online. Encyclopædia Britannica, Inc. Retrieved 16 January 2015.

- ^ "Germanic peoples". Encyclopædia Britannica Online. Encyclopædia Britannica, Inc. Retrieved 16 January 2015.

- ^ a b "Germany: Ancient History". Encyclopædia Britannica Online. Encyclopædia Britannica, Inc. Retrieved 16 January 2015.

- ^ a b Procopius. History of the Wars. Book III. II

- ^ "The Steppe: Early patterns of migration". Encyclopædia Britannica Online. Encyclopædia Britannica, Inc. Retrieved 17 January 2015.

- ^ Wolfram 1990, pp. 209–210

- ^ Kershaw 2013

- ^ Wolfram 1990, pp. 52–56

- ^ Bury

- ^ "The Steppe: Flourishing trade in the east". Encyclopædia Britannica Online. Encyclopædia Britannica, Inc. Retrieved 17 January 2015.

- ^ Kulikowski 2006, p. 19. "And so the Goths, when they first appear in our written sources, are Scythians – they lived where the Scythians had once lived, they were the barbarian mirror image of the civilised Greek world as the Scythians had been, and so they were themselves Scythians."

- ^ Kulikowski 2006, p. 15

- ^ Kulikowski 2006, p. 18

- ^ Bowman, Garnsey & Cameron 2005, pp. 223–229

- ^ a b G. Syncellus, p.717

- ^ Scriptores Historiae Augustae, Vita Gallienii, 13.8

- ^ Scriptores Historiae Augustae, Vita Gallienii, 13.8

- ^ a b Zosimus, 1.43

- ^ John Bray, p.290

- ^ The Historia Augusta mentions Scythians, Greuthungi, Tervingi, Gepids, Peucini, Celts and Heruli. Zosimus names Scythians, Heruli, Peucini and Goths.

- ^ Scriptores Historiae Augustae, Vita Divi Claudii, 6.4

- ^ Zosimus, 1.42

- ^ Contractus, Hermannus, Chronicon, quoting of Caesarea, Eusebius, Vita Constantini, p. 263: "Macedonia, Graecia, Pontus, Asia et aliae provinciae depopulantur per Gothos".

- ^ Tucker 2009, p. 150

- ^ a b Bowman, Garnsey & Cameron 2005, pp. 53–54

- ^ "6.32", Origo Constantini, mentions the actions.

- ^ Eusebius, "IV.6", Vita Constantini

- ^ Odahl, Charles Manson, "X", Constantine and the Christian Empire.

- ^ "Ancient Rome: The Reign of Constantine". Encyclopædia Britannica Online. Encyclopædia Britannica, Inc. Retrieved 16 January 2015.

- ^ Gottfried Schramm, Altrusslands Anfang. Historische Schlüsse aus Namen, Wörtern und Texten zum 9. und 10. Jahrhundert, Freiburg i. Br. 2002, p. 54.

- ^ "However, the seed and origin of all the ruin and various disasters that the wrath of Mars aroused ... we have found to be (the invasions of the Huns)", Marcellinus, Ammianus; tr. John Rolfe (1922), "2", Latin text and English translation, vol. XXXI, Loeb edition.

- ^ Beckwith 2009, pp. 81–83

- ^ Beckwith 2009, pp. 94–100

- ^ a b Beckwith 2009, pp. 331–332

- ^ Kulikowski 2006, p. 130.

- ^ Kulikowski 2006, p. 198

- ^ a b c Kulikowski 2006, pp. 145–147

- ^ Kulikowski 2006, p. 154

- ^ Moorhead & Stuttard 2010, p. 56

- ^ a b Cameron, Long & Sherry 1993, p. 99

- ^ Pohl, Walter. Strategies of Distinction: Construction of Ethnic Communities, 300–800 (Transformation of the Roman World. pp. 119–21. ISBN 90-04-10846-7..

- ^ Kristinsson 2010, p. 172

- ^ Pohl, Walter. Strategies of Distinction: Construction of Ethnic Communities, 300–800 (Transformation of the Roman World). pp. 124–6. ISBN 90-04-10846-7..

- ^ Ergo 12-1996.

- ^ Söderberg, Werner. (1896). "Nicolaus Ragvaldis tal i Basel 1434", in Samlaren, pp. 187–95.

- ^ Ambrose, On the Holy Ghost, book I, preface, paragraph 15

- ^ Edward Gibbon judged Ammianus "an accurate and faithful guide, who composed the history of his own times without indulging the prejudices and passions which usually affect the mind of a contemporary." (Gibbon, Edward, Decline and Fall of the Roman Empire, Chapter 26.5). But he also condemned Ammianus for lack of literary flair: "The coarse and undistinguishing pencil of Ammianus has delineated his bloody figures with tedious and disgusting accuracy." (Gibbon, Chapter 25.) Ernst Stein praised Ammianus as "the greatest literary genius that the world produced between Tacitus and Dante" (E. Stein, Geschichte des spätrömischen Reiches, Vienna 1928).

- ^ Craig H. Caldwell: Contesting late Roman Illyricum. Invasions and transformations in the Danubian-Balkan provinces. A dissertation presented to the Pricenton University in candidacy for the degree of doctor in philosophy. Quote: "The Life Of Probus like much of the rest of Historia Augusta is a more trustworthy source for its fourth-century audience then for its third-century subject"; Robert J. Edgeworthl (1992): More Fiction in the "Epitome". Steiner. Quote: "For a century it has been establish to general if not universal satisfaction, that biographies in Historia Augusta, especially after Caracalla, are a tissue of fiction and fabrication layered onto a thin thread of historical fact"; this view originates with Hermann Dessau.

Sources

- Andersson, Thorsten (1996). "Göter, goter, gutar". Namn och Bygd (in Swedish). 84. Uppsala: 5–21.

- Beckwith, Christopher I. (16 March 2009). Empires of the Silk Road: A History of Central Eurasia from the Bronze Age to the Present. Princeton University Press. ISBN 1400829941. Retrieved 30 December 2014.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Bell-Fialkoff, Andrew, Editor (2000). The Role of Migration in the History of the Eurasian Steppe: Sedentary Civilization vs. "Barbarian" and Nomad. New York: St. Martin's Press. ISBN 0-312-21207-0.

{{cite book}}:|first=has generic name (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Bowman, Alan; Garnsey, Peter; Cameron, Averil (8 September 2005). The Cambridge Ancient History: Volume 12, The Crisis of Empire, AD 193-337. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0521301998. Retrieved 17 January 2015.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Bradley, Henry (1888). The Goths: From the Earliest Times to the End of the Gothic Dominion in Spain. London: T. Fisher Unwin. ISBN 1-4179-7084-7. Downloadable Google Books.

- Bury, J. B. The Cambridge Medieval History Series volumes 1-5. Plantagenet Publishing. Retrieved 17 January 2015.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Cameron, Alan; Long, Jacqueline; Sherry, Lee (20 June 2013). Barbarians and Politics at the Court of Arcadius. University of California Press. ISBN 0520065506. Retrieved 17 January 2015.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Dabrowski, J. (1989) Nordische Kreis un Kulturen Polnischer Gebiete. Die Bronzezeit im Ostseegebiet. Ein Rapport der Kgl. Schwedischen Akademie der Literatur Geschichte und Alter unt Altertumsforschung über das Julita-Symposium 1986. Ed Ambrosiani, B. Kungl. Vitterhets Historie och Antikvitets Akademien. Konferenser 22. Stockholm.

- Oxenstierna, Graf E.C. (1948) [1945]. Die Urheimat der Goten. Leipzig, Mannus-Buecherei 73.

- Heather, Peter: The Goths (Blackwell, 1996)

- Hermodsson, Lars: Goterna — ett krigafolk och dess bibel, Stockholm, Atlantis, 1993.

- Jacobsen, Torsten Cumberland, The Gothic War: Rome's Final Conflict in the West. Yardley: Westholme, 2009. x, 371 p.

- Kaliff, Anders (2001), Gothic Connections: Contacts between Eastern Scandinavia and the Southern Baltic Coast, 1000 BC – 500 AD, Occasional Papers in Archaeology (OPIA), vol. 26, Uppsala

{{citation}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - Jūratė Statkutė de Rosales Balts and Goths : the missing link in European history, translation by Danutė Rosales ; supervised and corrected by Ed Tarvyd. Lemont, Ill. : Vydūnas Youth Fund, 2004.

- Kershaw, Stephen (20 June 2013). A Brief History of the Roman Empire. Hachette UK. ISBN 0520085116. Retrieved 17 January 2015.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Kristinsson, Axel (2010). Expansions: Competition and Conquest in Europe Since the Bronze Age. ReykjavíkurAkademían. ISBN 9979992212. Retrieved 17 January 2015.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Kulokowski, Michael (30 October 2006). Rome's Gothic Wars: From the Third Century to Alaric. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 1139458094. Retrieved 17 January 2015.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Mastrelli, Carlo Alberto in Volker Bierbauer et al., I Goti, Milan: Electa Lombardia, Elemond Editori Associati, 1994.

- Moorhead, Sam; Stuttard, David (2010). AD410: The Year that Shook Rome. Getty Publications. ISBN 1606060244. Retrieved 17 January 2015.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Nordgren, I.: Goterkällan — om goterna i Norden och på kontinenten, Skara: Vaestergoetlands museums skriftserie nr 30, 2000.

- Nordgren, I.: The Well Spring of the Goths: About the Gothic peoples in the Nordic Countries and on the Continent (2004).

- Rodin, L.; Lindblom, V; Klang, K.: Gudaträd och västgötska skottkungar – Sveriges bysantiska arv, Göteborg: Tre böcker, 1994.

- Schaetze der Ostgoten, Stuttgart: Theiss, 1995. Studia Gotica — Die eisenzeitlichen Verbindungen zwischen Schweden und Suedosteuropa — Vortraege beim Gotensymposion im Statens Historiska Museum, Stockholm 1970.

- Tacitus: Germania (with introduction and commentary by J.B. Rives), Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1999.

- Waldman, Carl; Mason, Catherine (2006). Encyclopedia of European Peoples. Infobase Publishing. ISBN 1438129181. Retrieved 16 January 2015.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Wenskus, Reinhard: Stammesbildung und Verfassung. Das Werden der Frühmittelalterlichen Gentes (Köln 1961).

- Wolfram, Herwig (1990). History of the Goths. University of California Press. ISBN 0520069838. Retrieved 16 January 2015.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Tucker, Spencer (23 December 2009). A Global Chronology of Conflict: From the Ancient World to the Modern Middle East. ABC-CLIO. ISBN 1851096728. Retrieved 17 January 2015.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Wolfram, Herwig (1997). The Roman Empire and Its Germanic Peoples. University of California Press. ISBN 0520085116. Retrieved 1 January 2015.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Wolfram, Herwig (1997). The Roman Empire and Its Germanic Peoples. University of California Press. ISBN 0520085116. Retrieved 1 January 2015.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help)

External links

- Forest People: The Goths in Transyvania, Hungary: NIIF

- The origin of the Goths (PDF), Neðerlands: Kortland

- . Collier's New Encyclopedia. 1921.

- Kaliff, Anders (2001). "Gothic Connections". Uppsala Universitet. Retrieved 30 October 2013.

- "The Savage Goths", Terry Jones' Barbarians, June 2006.

- Jordanes (1997), The Origins and Deeds of the Goths, Translated by Charles C. Mierow, Calgary: J. Vanderspoel, Department of Greek, Latin and Ancient History, University of Calgary, retrieved 5 September 2008

- Makiewicz, Tadeusz. "The Goths in Greater Poland". The Council of Europe, EuRoPol Gaz S.A. Retrieved 5 September 2008.

- Skorupka, Tomasz (1997). "Jewellery of the Goths". Translated by Rafal Witkowski. Poznan Archaeological Museum. Retrieved 16 September 2008.

- Hooker, Richard (1996). "The Germans". World Civilizations. Washington State University. Retrieved 19 September 2008.