Haplogroup J-M267: Difference between revisions

Undid revision 561714577 by Valentino2013 (talk) rvt major deletion of sourced material |

|||

| Line 360: | Line 360: | ||

====J-L147.1==== |

====J-L147.1==== |

||

J-L147.1 accounts for the majority of J-M267, the predominant haplogroup in Yemen {{harv|Chiaroni|2009}}. accounts for the majority of J-M267 in [[Yemen]], Cohen Jews and [[Ethiopia]] {{harv|Janzen|2013}} as well as [[Quraysh tribe|Quraysh]] including [[Seyyed]] {{harv|Quryish DNA Research Team|2013}} |

J-L147.1 accounts for the majority of J-M267, the predominant haplogroup in Yemen {{harv|Chiaroni|2009}}. accounts for the majority of J-M267 in [[Yemen]], Cohen Jews and [[Ethiopia]] {{harv|Janzen|2013}} as well as [[Quraysh tribe|Quraysh]] including [[Seyyed]] {{harv|Quryish DNA Research Team|2013}} |

||

=====YCAII=22-22===== |

|||

It is a Phyleltic clade inside L-147. YCAII is a very slow STR marker and it is at 22-22 in 70-90% in Arabs with [[Japlogroup J1]] and very frequent in Jews with [[Haplogroup J1]], but YCAII=22-22 is much less frequest in Ethiopians and rare in [[J1]] in Europe and Caucasus. |

|||

======The "DYS388≥16" cluster====== |

|||

When Y STR marker found in all males is DYS388>16 in males with [[J1]] haplogroup it is specific in Arabs with [[J1]], but rare in J1 Jews who are typically DYS388=16. The Arabic expansion in 7th century spread the combination of the two STR markers DYS388=17 accompanied by STR marker YCAII=22-22 was spread by the Arabic expansion in the 7th century. |

|||

Not only is the J-P58 group itself very dominant in many areas where J-M267 is common, but J-P58 in turn contains a large cluster which had been recognized before the discovery of P58 and its subclade L147, and is still a subject of research. This relatively young cluster, inside J-M267 overall, was identified by [[short tandem repeat|STR marker]]s YCAII at 22-22, and DYS388 having at 17 or higher, instead of 16 or 15 {{harv|Chiaroni|2011}} while DYS388<15 is very rare and found only in Europe and Caucasus). This cluster was found in Modal Haplotype of Palestinian populations ({{harvnb|Nebel|2000}} and {{harvnb|Hammer|2009}}) and later confirmed its prevalance in Arabs. More generally, since then this cluster has been found to be frequent among men in the Middle East and North Africa, but less frequent in [[J1]] men in Ethiopia ( J1-M267 is 30 % in Amhari men) and Europe where J1-M267 is rare. The pattern is therefore similar to the pattern of J-P58 generally, described above, and may be caused by the same movements of people {{harv|Chiaroni|2009}}. The Ancient Immigration of J1 men in Neolithic times (stone age) brought J1 (with rare YCAII=22-22 ) in to Europe and Ethiopia while more recent (less than 4000 years before present) immigration to Middle East and North Africa (Semino 2004). Semino consider YCAII=22-22 in j1, a monophyletic clade. |

|||

Now almost all J1 with ycaii=22-22 is found in the J1 Lineage L147 (L147 is the Cohan Modal Haplotype in J1). Finding YCAII=22-22 in J1 male classify him as having L147 or CMH, because YCAII and CMH (L147) are associated (majority of CMH have YCAII=22-22 while YCAII=22-22 is rare outside CL147 clade (males with haplogroup J1 and CMH).CMH is found in other haplogroups such as J2 and Q and E etc. as (Haplotype Convergence= Random coincidence). |

|||

{{harvnb|Tofanelli|2009}} refers to this overall cluster with YCAII=22-22 and high DYS388 values above 16 as an "Arabic" meaning finding a person with J1 Haplogroup and him also having YCAII=22-22 and DYS388=17 or over is specific to Arabs . This Arabic includes [[Arabic]] speakers from [[Maghreb]], [[Sudan]], [[Iraq]] and [[Qatar]], and it is a relatively homogeneous group, implying that it might have dispersed relatively recently compared to J-M267. The more diverse Hasplogroup J1 is found in [[Europeans]] J1=.5% of Europpeans) , [[Kurds]] (18% of Kurds are J1), and [[Ethiopians]] (30% of Amhari are J1). The authors also say that "Omanis show a high diversity of [[J1]]Arabic, considering the role of corridor played at different times by the Gulf of Oman in the dispersal of [[Asia]]n and [[East Africa]]n [[genes]]." {{harvnb|Chiaroni|2009}} also noted the anomalously high number of Most Common ancestor of J1 Omani when compared with other Arabic countries. High diversity of Haplotype in side of a Haplogroup indicate a more distant in the past of a common ancestor. The older the start of a haplotype ( a one man with specific haplogroup) the more diversity it will have between all his decendents at present.Recent in Genetic geneology means less than 4000 years bpe (before present). |

|||

The J1-Cohan Modal Haplotype cluster which is (lineage L147 inside P58 inside J1 ) in turn contains known related sub-clusters. First, it contains the majority of the Jewish "[[Cohen modal haplotype]]", found among Jewish populations, but especially in men with surnames related to Cohen. It also contains both the ''Galilee [[modal haplotype|modal]] haplotype'' and ''Palestinian & Israeli Arab modal [[haplotype]]'' associated with Palestinians and [[Israeli Arabs]] by {{harvnb|Nebel|2000}} and {{harvnb|Hammer|2009}}. {{harvnb|Nebel|2002}} then pointed out that the ''Galilee modal'' ( now part of J1-CMH) is found in Palestinians in Gelilee, in Moroccan Arabs and In San'a Yemen. |

|||

{{harvnb|Nebel|2002}} noted not only the presence of the Galilee modal of J-M267 in the [[Maghreb]] but also that J-M267 in this region had very little diversity generally (meaning all of them came from a more recent ancestor in the last 4000 years ) They concluded that J-M267 in this region "is derived not only from the early Neolithic dispersion but also from recent expansions from the Arabian peninsula" proposing that they might have been carried from the Middle East with the [[Arab expansion]] in the seventh century AD. {{harvnb|Semino|2004}} later agreed that this seemed consistent with the evidence and generalized from this that distribution of the entire YCAII=22-22 cluster of J-M267 in the Arabic speaking areas of the Middle East and North Africa might in fact mainly have an origin in historical times. |

|||

More recent studies have emphasized doubt that the Islamic expansions are old enough to completely explain the major patterns of J-M267 frequencies. {{harvnb|Chiaroni|2009}} rejected this for J-P58 as a whole, but accepted that "some of the populations with low diversity, such as Bedouins from Israel, Qatar, Sudan and UAE, are tightly clustered near high-frequency haplotypes suggesting founder effects with star burst expansion in the Arabian Desert". They did not comment on the Maghreb. |

|||

{{harvnb|Tofanelli|2009}} take a stronger position of rejecting any strong correlation between the Arab expansion and either the YCAII=22-22 STR-defined sub-cluster as discussed by {{harvnb|Semino|2004}} or the smaller "Galilee modal" as discussed by {{harv|Nebel|2002}}. They also estimate that the Cohen modal haplotype must be older than 4500 years old, and maybe as much as 8600 years old - well before the supposed origin of the Cohanim. Only the so-called Palestinian & Israeli Arab modal had a strong correlation to an ethnic group, but it was also rare. In conclusion, the authors were negative about the usefulness of STR defined modals for any "forensic or genealogical purposes" because "they were found across ethnic groups with different cultural or geographic affiliation". |

|||

{{harvnb|Hammer|2009}} disagreed, at least concerning the Cohen modal haplotype. They said that it was necessary to look at a more detailed STR haplotype in order to define a new "Extended Cohen Modal Haplotype" which is extremely rare outside Jewish populations, and even within Jewish populations is mainly only found in Cohanim. They also said that by using more markers and a more restrictive definition, the estimated age of the Cohanim lineage is lower than the estimates of {{harvnb|Tofanelli|2009}}, and it is consistent with a common ancestor at the approximate time of founding of the priesthood which is the source of Cohen surnames. |

|||

====J-L222.2==== |

====J-L222.2==== |

||

Revision as of 20:48, 26 June 2013

| Haplogroup J-M267 | |

|---|---|

| |

| Possible time of origin | 4,000-34,000 years before present (Di Giacomo 2004) |

| Possible place of origin | Western Asia |

| Ancestor | J-P209 |

| Descendants | J-M62, J-M365.1, J-L136, J-Z1828 |

| Defining mutations | M267, L255, L321, L765, L814, L827, L1030 |

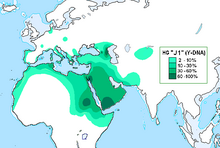

In human genetics, Y DNA haplogroup J-M267[Phylogenetics 1] is a subclade (branch) of Y-DNA haplogroup J-P209,[Phylogenetics 2] along with its sibling clade Y DNA haplogroup J-M172. Men from this lineage share a common paternal ancestor, which is demonstrated and defined by the presence of the SNP mutation referred to as M267, which was announced in (Cinnioğlu 2004). This haplogroup is found today in significant frequencies in many areas in order near the Middle East. For example it is among the most frequent haplogroups in Arabian Peninsula, and parts of the Caucasus, Sudan and the Horn of Africa. It is also found in high frequencies in parts of North Africa Jewish groups especially those with Cohen surnames. It can also be found much less commonly, but still occasionally in significant amounts, in Europe and as far east as the Central Asia.

Origins

As a basic observation, since the discovery of haplogroup J-P209[Phylogenetics 2] it has generally been recognized that it shows signs of having originated in or near West Asia. The frequency and diversity of both J-M267 and J-M172 in that region makes them candidates as genetic markers of the spread of farming technology during the Neolithic, which is proposed to have had a major impact upon human populations.

J-M267 has several recognized subclades, some of which were recognized before J-M267 itself was recognized, for example J-M62 Y Chromosome Consortium "YCC" 2002. With one notable exception, J-P58, most of these are not common (Tofanelli 2009). Because of the dominance of J-P58 in J-M267 populations in many areas, discussion of J-M267's origins require a discussion of J-P58 at the same time.

Distribution

Africa

North Africa

North Africa received Semitic migrations, according to some studies it may have been diffused in recent time by Arabs who, mainly from the 7th century a.d., expanded to northern Africa (Arredi 2004 and Semino 2004). However the Canary islands is not known to have had any Semitic language. There J-M267 is dominated by J-P58, and dispersed in a very uneven manner according to studies so far, often but not always being lower among Berber and/or non-urban populations. In Ethiopia there are signs of older movements of J-M267 into Africa across the Red Sea, not only in the J-P58 form. This also appears to be associated with Semitic languages. According to a study in 2011, in Tunisia, J-M267 is significantly more abundant in the urban (31.3%) than in the rural total population (2.5%). According to the authors, these results could be explained by supposing that Arabization in Tunisia was a military enterprise, therefore, mainly driven by men that displaced native Berbers to geographically marginal areas but that frequently married Berber women (Ennafaa 2011).

| Population | Sample size | J-M267(xJ-M172) | total J-M267 | J-M267(xP58) | J-P58 | publication | previous research on same samples |

| Algeria (Arabs from Oran) | 102 | NA | 22.5% | NA | NA | Robino 2007 | |

| Algeria | 20 | NA | 35% | NA | NA | Semino 2004 | |

| Egypt | 147 | NA | 21.1% | 1.4% | 19.7% | Chiaroni 2009 | Luis 2004 |

| Egypt | 124 | NA | 19.8% | NA | NA | El-Sibai 2009 | |

| Egypt (Western Desert) | 35 | NA | 31.4% | NA | NA | Kujanová 2009 | |

| Libya (Tuareg) | 47 | NA | 0.0% | NA | NA | Ottoni 2011 | |

| Morocco (Amizmiz Valley) | 33 | NA | 0% | NA | NA | Alvarez 2009 | |

| Morocco | 51 | NA | 19.6% | NA | NA | Onofri 2008 | |

| Morocco (Arabs) | 49 | NA | 10.2% | NA | NA | Semino 2004 | |

| Morocco (Arabs) | 44 | NA | 13.6% | NA | NA | Semino 2004 | |

| Morocco (Berbers) | 64 | NA | 6.3% | NA | NA | Semino 2004 | |

| Morocco (Berbers) | 103 | NA | 7.8% | NA | NA | Semino 2004 | |

| Tunisia | 73 | NA | 30.1% | NA | NA | Semino 2004 | |

| Tunisia (Tunis) | 148 | NA | 32.4% | 1.3% | 31.1% | Grugni 2012 | Arredi 2004 |

| Tunisia | 52 | NA | 34.6% | NA | NA | Onofri 2008 | |

| Tunisia (Bou Omrane Berbers) | 40 | NA | 0% | NA | NA | Ennafaa 2011 | |

| Tunisia (Bou Saad Berbers) | 40 | NA | 5% | 0% | 5% | Ennafaa 2011 | |

| Tunisia (Jerbian Arabs) | 46 | NA | 8.7% | NA | NA | Ennafaa 2011 | |

| Tunisia (Jerbian Berbers) | 47 | NA | 0% | NA | NA | Ennafaa 2011 | |

| Tunisia (Sened Berbers) | 35 | NA | 31.4% | 0% | 31.4% | Fadhlaoui-Zid 2011 | |

| Tunisia (Andalusian Zaghouan) | 32 | NA | 43.8% | 0% | 43.8% | Fadhlaoui-Zid 2011 | |

| Tunisia (Cosmopolitan Tunis) | 33 | NA | 24.2 | 0% | 24.2% | Fadhlaoui-Zid 2011 | |

| Canary Islands (pre-Hispanic) | 30 | NA | 16.7% | NA | NA | Fregel 2009 | |

| Canary Islands (17th-18thC)) | 42 | NA | 11.9% | NA | NA | Fregel 2009 | |

| Canary Islands | 652 | NA | 3.5% | NA | NA | Fregel 2009 | |

| Sahrawi | 89 | NA | 20.2% | NA | NA | Fregel 2009 | Bosch 2001 and Flores 2001 |

| Sudan (Khartoum) | 35 | NA | 74.3% | 0.0% | 74.3% | Chiaroni 2009 | Tofanelli 2009 and Hassan 2008 |

| Sudan-Arabic | 35 | NA | 17.1% | 0.0% | 17.1% | Chiaroni 2009 | Hassan 2008 |

| Sudan (Nilo-Saharan languages) | 61 | NA | 4.9% | 3.3% | 1.6% | Chiaroni 2009 | Hassan 2008 |

| Ethiopia Oromo | 78 | NA | 2.6% | 2.6% | 0.0% | Chiaroni 2009 | Semino 2004 |

| Ethiopia Amhara | 48 | NA | 29.2% | 8.3% | 20.8% | Chiaroni 2009 | Semino 2004 |

| Ethiopia Arsi | 85 | 22% | NA | NA | NA | Moran 2004 | |

| Ethiopia General | 95 | 21% | NA | NA | NA | Moran 2004 | |

| Comoros Islands | 293 | NA | 5.0% | NA | NA | Msaidie 2011 |

Asia

West Asia

The area including eastern Turkey and the Zagros and Taurus mountains, has been identified as a likely area of ancient J-M267 diversity. Both J-P58 and other types of J-M267 are present, sometimes with similar frequencies.

| Population | Sample size | Total J-M267 | J-M267(xP58) | J-P58 | Publication | Previous research on same samples |

| Turkey | 523 | 9.0% | 3.1% | 5.9% | Chiaroni 2009 | Cinnioğlu 2004 |

| Iran | 150 | 11.3% | 2.7% | 8.7% | Chiaroni 2009 | Regueiro 2006 |

| Kurds Iraq | 93 | 11.8% | 4.3% | 7.5% | Chiaroni 2009 | |

| Assyrians modern Iraq | 28 | 28.6% | 17.9% | 10.7% | Chiaroni 2009 | |

| Iraq (Nassiriya) | 56 | 26.8% | 1.8% | 25.0% | Chiaroni 2009 | Tofanelli 2009 |

| Assyrians Iran | 31 | 16.1% | 9.7% | 6.5% | Chiaroni 2009 | |

| Iran | 92 | 3.2% | NA | NA | El-Sibai 2009 | |

| Assyrians Turkey | 25 | 20.0% | 16.0% | 4.0% | Chiaroni 2009 |

Levant and Jewish populations

J-M267 is very common throughout this region, dominated by J-P58, but some specific sub-populations have notably low frequencies.

| Population | Sample size | Total J-M267 | J-M267(xP58) | J-P58 | Publication | Previous research on same samples |

| Syria | 554 | 33.6% | NA | NA | El-Sibai 2009 | Zalloua 2008 |

| Druzes (Djebel Druze) | 34 | 14.7% | 2.9% | 11.8% | Chiaroni 2009 | |

| Syria (Sunni from Hama) | 36 | 47.2% | 2.8% | 44.4% | Chiaroni 2009 | |

| Syria (Ma'loula Aramaean) | 44 | 6.8% | 4.5% | 2.3% | Chiaroni 2009 | |

| Syria (Sednaya Syriac Catholic) | 14 | 14.3% | 0.0% | 14.3% | Chiaroni 2009 | |

| Syrian Catholic Damascus | 42 | 9.5% | 0.0% | 9.5% | Chiaroni 2009 | |

| Alawites Syria | 45 | 26.7% | 0.0% | 26.7% | Chiaroni 2009 | |

| Assyrian NE Syria | 30 | 3.3% | 0.0% | 3.3% | Chiaroni 2009 | |

| Ismaili Damascus | 51 | 58.8% | 0.0% | 58.8% | Chiaroni 2009 | |

| Lebanon | 951 | 18.9% | NA | NA | Zalloua 2008 | |

| Galilee Druze | 172 | 13.4% | 1.2% | 12.2% | Chiaroni 2009 | Shlush 2008 |

| Palestinians (Akka (Acre)) | 101 | 39.2% | NA | NA | Zalloua 2008 | |

| Palestine | 49 | 32.7% | 0.0% | 32.7% | Chiaroni 2009 | |

| Jordan | 76 | 48.7% | 0.0% | 48.7% | Chiaroni 2009 | |

| Jordan | 273 | 35.5% | NA | NA | El-Sibai 2009 | |

| Jordan (Amman) | 101 | 40.6% | NA | NA | Flores 2005 | |

| Jordan (Dead Sea) | 45 | 8.9% | NA | NA | Flores 2005 | |

| Jews (Portugal/Trás-os-Montes) | 57 | 12.3% | NA | NA | Nogueiro 2009 | |

| Jews (Cohanim) | 215 | 46.0% | 0.0% | 46.0% | Hammer & Behar 2009 | |

| Jews (non Cohanim) | 1,360 | 14.9% | 0.9% | 14.0% | Hammer 2009 | |

| Bedouin Negev | 28 | 67.9% | 3.6% | 64.3% | Chiaroni 2009 | Cann 2002 |

Arabian peninsula

J-P58 is the most common Y-Chromosome haplogroup among men from all of this region.

| Population | Sample size | Total J-M267 | J-M267(xP58) | J-P58 | Publication | Previous research on same samples |

| Saudi Arabia | 12 | 33.3% | 0.0% | 33.3% | Chiaroni 2009 | Tofanelli 2009 |

| Saudi Arabia | 157 | 40.1% | NA | NA | Abu-Amero 2009 | |

| Qatar | 72 | 58.3% | 1.4% | 56.9% | Chiaroni 2009 | Cadenas 2007 |

| UAE | 164 | 34.8% | 0.0% | 34.8% | Chiaroni 2009 | Cadenas 2007 |

| Yemen | 62 | 72.6% | 4.8% | 67.7% | Chiaroni 2009 | Cadenas 2007 |

| Kuwait | 42 | 33.3% | NA | NA | El-Sibai 2009 | |

| Oman | 121 | 38.0% | 0.8% | 37.2% | Chiaroni 2009 | Luis 2004 |

Europe

J-M267 is uncommon in most of Europe, but it is found in some sub-populations in southern Europe.

| Population | Sample size | Total J-M267 | J-M267(xP58) | J-P58 | publication |

| Crete | 193 | 8.3% | NA | NA | King 2008 |

| Greece (mainland) | 171 | 4.7% | NA | NA | King 2008 |

| Macedonia (Greece) | 56 | 1.8% | NA | NA | Semino 2004 |

| Greece | 249 | 1.6% | NA | NA | Di Giacomo 2004 |

| Bulgaria | 39 | 5.1% | NA | NA | Di Giacomo 2004 |

| Romania | 130 | 1.5% | NA | NA | Di Giacomo 2004 |

| Russia | 223 | 0.4% | NA | NA | Di Giacomo 2004 |

| Republic of Macedonia Albanian speakers | 64 | 6.3% | NA | NA | Battaglia 2008 |

| Albania | 56 | 3.6% | NA | NA | Semino 2004 |

| Croats (Osijek) | 29 | 0.0% | NA | NA | Battaglia 2008 |

| Slovenia | 75 | 1.3% | NA | NA | Battaglia 2008 |

| Italians (northeast) | 67 | 0.0% | NA | NA | Battaglia 2008 |

| Italians | 915 | 0.7% | NA | NA | Capelli 2009 |

| Sicily | 236 | 3.8% | NA | NA | Di Gaetano 2008 |

| Provence | 51 | 2% | NA | NA | King 2011 |

| Portugal (North) | 101 | 1.0% | NA | NA | Gonçalves 2005 |

| Portugal (Centre) | 102 | 4.9% | NA | NA | Gonçalves 2005 |

| Portugal (South) | 100 | 7.0% | NA | NA | Gonçalves 2005 |

| Açores | 121 | 2.5% | NA | NA | Gonçalves 2005 |

| Madeira | 129 | 0.0% | NA | NA | Gonçalves 2005 |

Caucasus

The Caucasus has areas of both high and low J-M267 frequency. The J-M267 in the Caucasus is also notable because most of it is not within the J-P58 subclade.

| Population | Sample size | Total J-M267 | J-M267(xP58) | J-P58 | Publication |

| Avars | 115 | 59.0% | 58.0% | 1.0% | Balanovsky 2011 |

| Dargins | 101 | 70.0% | 69.0% | 1.0% | Balanovsky 2011 |

| Kubachi | 65 | 99.0% | 99.0% | 0.0% | Balanovsky 2011 |

| Kaitak | 33 | 85.0% | 85.0% | 0.0% | Balanovsky 2011 |

| Lezghins | 81 | 44.4% | 44.4% | 0.0% | Balanovsky 2011 |

| Shapsug | 100 | 0.0% | 0.0% | 0.0% | Balanovsky 2011 |

| Abkhaz | 58 | 0.0% | 0.0% | 0.0% | Balanovsky 2011 |

| Circassians | 142 | 11.9% | 4.9% | 7.0% | Balanovsky 2011 |

| Ingush | 143 | 2.8% | 2.8% | 0.0% | Balanovsky 2011 |

| Ossets | 357 | 1.3% | 1.3% | 0.0% | Balanovsky 2011 |

| Chechens (Ingushetia) | 112 | 21.0% | 21.0% | 0.0% | Balanovsky 2011 |

| Chechens (Chechnya) | 118 | 25.0% | 25.0% | 0.0% | Balanovsky 2011 |

| Chechens (Dagestan) | 100 | 16.0% | 16.0% | 0.0% | Balanovsky 2011 |

| Azerbaijan | 46 | 15.2% | NA | NA | Di Giacomo 2004 |

Subclade Distribution

J-P58

J-P58 (AKA J-PAGE8) is found in a low frequency in the Levant and the Arabian Peninsula (Janzen 2013).

The P58 marker which defines subgroup J-P58 was announced in (Karafet 2008), but had been announced earlier under the name Page08 in (Repping 2006 and called that again in Chiaroni 2011). It is very prevalent in many areas where J-M267 is common, especially in parts of North Africa and throughout the Arabian peninsula. It also makes up approximately 70% of the J-M267 among the Amhara of Ethiopia. Notably, it is not common among the J-M267 populations in the Caucasus.

Chiaroni 2009 proposed that J-P58 (that they refer to as J1e) might have first dispersed during the Pre-Pottery Neolithic B period, "from a geographical zone, including northeast Syria, northern Iraq and eastern Turkey toward Mediterranean Anatolia, Ismaili from southern Syria, Jordan, Palestine and northern Egypt." They further propose that the Zarzian material culture may be ancestral. They also propose that this movement of people may also be linked to the dispersal of Semitic languages by hunter-herders, who moved into arid areas during periods known to have had low rainfall. Thus, while other haplogroups including J-M172 moved out of the area with agriculturalists who followed the rainfall, populations carrying J-M267 remained with their flocks) (King 2002 and Chiaroni 2008).

According to this scenario, after the initial neolithic expansion involving Semitic languages, which possibly reached as far as Yemen, a more recent dispersal occurred during the Chalcolithic or Early Bronze Age (approximately 3000–5000 BCE), and this involved the branch of Semitic which leads to the Arabic language. The authors propose that this involved a spread of some J-P58 from the direction of Syria towards Arab populations of the Arabian Peninsula and Negev.

On the other hand, the authors agree that later waves of dispersion in and around this area have also had complex effects upon the distributions of some types of J-P58 in some regions. They list three regions which are particularly important to their proposal:

- The Levant (Syria, Jordan, Israel and Palestine). In this area, Chiaroni 2009 note a "patchy distribution of J1e frequency" which is difficult to interpret, and which "may reflect the complex demographic dynamics of religion and ethnicity in the region".

- The northern area of eastern Anatolia, northern Iraq and northwest Iran. In this area, Chiaroni 2009 recognize signs that J-M267 might have an older presence, and on balance they accept the evidence but note that it could be in error.

- The southern area of Oman, Yemen and Ethiopia. In this area, Chiaroni 2009 recognize similar signs, but reject it as possible a result of "either sampling variability and/or demographic complexity associated with multiple founders and multiple migrations."

The "YCAII=22-22 and DYS388≥15" cluster

Not only is the J-P58 group itself very dominant in many areas where J-M267 is common, but J-P58 in turn contains a large cluster which had been recognized before the discovery of P58, and is still a subject of research. This relatively young cluster, compared to J-M267 overall, was identified by STR markers haplotypes - specifically YCAII as 22-22, and DYS388 having unusual repeat values of 15 or higher, instead of more typical 13 (Chiaroni 2011) This cluster was found to be relevant in some well-publicized studies of Jewish and Palestinian populations (Nebel 2000 and Hammer 2009). More generally, since then this cluster has been found to be frequent among men in the Middle East and North Africa, but less frequent in areas of Ethiopia and Europe where J-M267 is nevertheless common. The pattern is therefore similar to the pattern of J-P58 generally, described above, and may be caused by the same movements of people (Chiaroni 2009).

Tofanelli 2009 refers to this overall cluster with YCAII=22-22 and high DYS388 values as an "Arabic" as opposed to a "Eurasian" type of J-M267. This Arabic type includes Arabic speakers from Maghreb, Sudan, Iraq and Qatar, and it is a relatively homogeneous group, implying that it might have dispersed relatively recently compared to J-M267 generally. The more diverse "Eurasian" group includes Europeans, Kurds, Iranians and Ethiopians (despite Ethiopia being outside of Eurasia), and is much more diverse. The authors also say that "Omanis show a mix of Eurasian pool-like and typical Arabic haplotypes as expected, considering the role of corridor played at different times by the Gulf of Oman in the dispersal of Asian and East African genes." Chiaroni 2009 also noted the anomalously high apparent age of Omani J-M267 when looking more generally at J-P58 and J-M267 more generally.

This cluster in turn contains three well-known related sub-clusters. First, it contains the majority of the Jewish "Cohen modal haplotype", found among Jewish populations, but especially in men with surnames related to Cohen. It also contains both the Galilee modal haplotype and Palestinian & Israeli Arab modal haplotype associated with Palestinians and Israeli Arabs by Nebel 2000 and Hammer 2009. Nebel 2002 then pointed out that the Galilee modal is also the most frequent type of J-P209 haplotype found in northwest Africans, and in Yemen, so it is not isolated to the area of Israel and the Palestine. But notably, this particular variant "is absent from two distinct non-Arab Middle Eastern populations, Jews and Muslim Kurds", even though both these populations do have high levels of J-P209 haplotypes.

Nebel 2002 noted not only the presence of the Galilee modal of J-M267 in the Maghreb but also that J-M267 in this region had very little diversity generally. They concluded that J-M267 in this region "is derived not only from the early Neolithic dispersion but also from recent expansions from the Arabian peninsula" proposing that they might have been carried from the Middle East with the Arab expansion in the seventh century AD. Semino 2004 later agreed that this seemed consistent with the evidence and generalized from this that distribution of the entire YCAII=22-22 cluster of J-M267 in the Arabic speaking areas of the Middle East and North Africa might in fact mainly have an origin in historical times.

More recent studies have emphasized doubt that the Islamic expansions are old enough to completely explain the major patterns of J-M267 frequencies. Chiaroni 2009 rejected this for J-P58 as a whole, but accepted that "some of the populations with low diversity, such as Bedouins from Israel, Qatar, Sudan and UAE, are tightly clustered near high-frequency haplotypes suggesting founder effects with star burst expansion in the Arabian Desert". They did not comment on the Maghreb.

Tofanelli 2009 take a stronger position of rejecting any strong correlation between the Arab expansion and either the YCAII=22-22 STR-defined sub-cluster as discussed by Semino 2004 or the smaller "Galilee modal" as discussed by (Nebel 2002). They also estimate that the Cohen modal haplotype must be older than 4500 years old, and maybe as much as 8600 years old - well before the supposed origin of the Cohanim. Only the so-called Palestinian & Israeli Arab modal had a strong correlation to an ethnic group, but it was also rare. In conclusion, the authors were negative about the usefulness of STR defined modals for any "forensic or genealogical purposes" because "they were found across ethnic groups with different cultural or geographic affiliation".

Hammer 2009 disagreed, at least concerning the Cohen modal haplotype. They said that it was necessary to look at a more detailed STR haplotype in order to define a new "Extended Cohen Modal Haplotype" which is extremely rare outside Jewish populations, and even within Jewish populations is mainly only found in Cohanim. They also said that by using more markers and a more restrictive definition, the estimated age of the Cohanim lineage is lower than the estimates of Tofanelli 2009, and it is consistent with a common ancestor at the approximate time of founding of the priesthood which is the source of Cohen surnames.

J-M368

The correspondence between P58 and high DYS388 values, and YCAII=22-22 is not perfect. For example the J-M368 subclade of J-P58 defined by SNP M368 has DYS388=13 and YCAII=19-22, like other types of J-M267 outside the "Arabic" type of J-M267, and it is therefore believed to be a relatively old offshoot of J-P58, that did not take part in the most recent waves of J-M267 expansion in the Middle East (Chiaroni 2009). These DYS388=13 haplotypes are most common in the Caucasus and Anatolia, but also found in Ethiopia (Tofanelli 2009).

J-M267

J-M267 clusters are found in Eastern Anatolia & parts of the Caucasus (Givargidze & Hrechdakian 2013).

J-M62

J-M62 is found in a very small frequency in Britain.

J-M365.1

J-M365.1 is found in a small frequency in Eastern Anatolia, Iran & parts of Europe (Costa de Oliveira 2013).

J-L136

J-L136 if found in a very small frequency in Europe (Janzen 2013).

J-P56

J-P56 is found sporadically in Anatolia, East Africa, the Arabian Peninsula & Europe (Janzen 2013).

J-L92

J-L92 is found in a small frequency in South Arabia (Janzen 2013).

J-L147.1

J-L147.1 accounts for the majority of J-M267, the predominant haplogroup in Yemen (Chiaroni 2009). accounts for the majority of J-M267 in Yemen, Cohen Jews and Ethiopia (Janzen 2013) as well as Quraysh including Seyyed (Quryish DNA Research Team 2013)

YCAII=22-22

It is a Phyleltic clade inside L-147. YCAII is a very slow STR marker and it is at 22-22 in 70-90% in Arabs with Japlogroup J1 and very frequent in Jews with Haplogroup J1, but YCAII=22-22 is much less frequest in Ethiopians and rare in J1 in Europe and Caucasus.

The "DYS388≥16" cluster

When Y STR marker found in all males is DYS388>16 in males with J1 haplogroup it is specific in Arabs with J1, but rare in J1 Jews who are typically DYS388=16. The Arabic expansion in 7th century spread the combination of the two STR markers DYS388=17 accompanied by STR marker YCAII=22-22 was spread by the Arabic expansion in the 7th century. Not only is the J-P58 group itself very dominant in many areas where J-M267 is common, but J-P58 in turn contains a large cluster which had been recognized before the discovery of P58 and its subclade L147, and is still a subject of research. This relatively young cluster, inside J-M267 overall, was identified by STR markers YCAII at 22-22, and DYS388 having at 17 or higher, instead of 16 or 15 (Chiaroni 2011) while DYS388<15 is very rare and found only in Europe and Caucasus). This cluster was found in Modal Haplotype of Palestinian populations (Nebel 2000 and Hammer 2009) and later confirmed its prevalance in Arabs. More generally, since then this cluster has been found to be frequent among men in the Middle East and North Africa, but less frequent in J1 men in Ethiopia ( J1-M267 is 30 % in Amhari men) and Europe where J1-M267 is rare. The pattern is therefore similar to the pattern of J-P58 generally, described above, and may be caused by the same movements of people (Chiaroni 2009). The Ancient Immigration of J1 men in Neolithic times (stone age) brought J1 (with rare YCAII=22-22 ) in to Europe and Ethiopia while more recent (less than 4000 years before present) immigration to Middle East and North Africa (Semino 2004). Semino consider YCAII=22-22 in j1, a monophyletic clade. Now almost all J1 with ycaii=22-22 is found in the J1 Lineage L147 (L147 is the Cohan Modal Haplotype in J1). Finding YCAII=22-22 in J1 male classify him as having L147 or CMH, because YCAII and CMH (L147) are associated (majority of CMH have YCAII=22-22 while YCAII=22-22 is rare outside CL147 clade (males with haplogroup J1 and CMH).CMH is found in other haplogroups such as J2 and Q and E etc. as (Haplotype Convergence= Random coincidence).

Tofanelli 2009 refers to this overall cluster with YCAII=22-22 and high DYS388 values above 16 as an "Arabic" meaning finding a person with J1 Haplogroup and him also having YCAII=22-22 and DYS388=17 or over is specific to Arabs . This Arabic includes Arabic speakers from Maghreb, Sudan, Iraq and Qatar, and it is a relatively homogeneous group, implying that it might have dispersed relatively recently compared to J-M267. The more diverse Hasplogroup J1 is found in Europeans J1=.5% of Europpeans) , Kurds (18% of Kurds are J1), and Ethiopians (30% of Amhari are J1). The authors also say that "Omanis show a high diversity of J1Arabic, considering the role of corridor played at different times by the Gulf of Oman in the dispersal of Asian and East African genes." Chiaroni 2009 also noted the anomalously high number of Most Common ancestor of J1 Omani when compared with other Arabic countries. High diversity of Haplotype in side of a Haplogroup indicate a more distant in the past of a common ancestor. The older the start of a haplotype ( a one man with specific haplogroup) the more diversity it will have between all his decendents at present.Recent in Genetic geneology means less than 4000 years bpe (before present).

The J1-Cohan Modal Haplotype cluster which is (lineage L147 inside P58 inside J1 ) in turn contains known related sub-clusters. First, it contains the majority of the Jewish "Cohen modal haplotype", found among Jewish populations, but especially in men with surnames related to Cohen. It also contains both the Galilee modal haplotype and Palestinian & Israeli Arab modal haplotype associated with Palestinians and Israeli Arabs by Nebel 2000 and Hammer 2009. Nebel 2002 then pointed out that the Galilee modal ( now part of J1-CMH) is found in Palestinians in Gelilee, in Moroccan Arabs and In San'a Yemen.

Nebel 2002 noted not only the presence of the Galilee modal of J-M267 in the Maghreb but also that J-M267 in this region had very little diversity generally (meaning all of them came from a more recent ancestor in the last 4000 years ) They concluded that J-M267 in this region "is derived not only from the early Neolithic dispersion but also from recent expansions from the Arabian peninsula" proposing that they might have been carried from the Middle East with the Arab expansion in the seventh century AD. Semino 2004 later agreed that this seemed consistent with the evidence and generalized from this that distribution of the entire YCAII=22-22 cluster of J-M267 in the Arabic speaking areas of the Middle East and North Africa might in fact mainly have an origin in historical times.

More recent studies have emphasized doubt that the Islamic expansions are old enough to completely explain the major patterns of J-M267 frequencies. Chiaroni 2009 rejected this for J-P58 as a whole, but accepted that "some of the populations with low diversity, such as Bedouins from Israel, Qatar, Sudan and UAE, are tightly clustered near high-frequency haplotypes suggesting founder effects with star burst expansion in the Arabian Desert". They did not comment on the Maghreb.

Tofanelli 2009 take a stronger position of rejecting any strong correlation between the Arab expansion and either the YCAII=22-22 STR-defined sub-cluster as discussed by Semino 2004 or the smaller "Galilee modal" as discussed by (Nebel 2002). They also estimate that the Cohen modal haplotype must be older than 4500 years old, and maybe as much as 8600 years old - well before the supposed origin of the Cohanim. Only the so-called Palestinian & Israeli Arab modal had a strong correlation to an ethnic group, but it was also rare. In conclusion, the authors were negative about the usefulness of STR defined modals for any "forensic or genealogical purposes" because "they were found across ethnic groups with different cultural or geographic affiliation".

Hammer 2009 disagreed, at least concerning the Cohen modal haplotype. They said that it was necessary to look at a more detailed STR haplotype in order to define a new "Extended Cohen Modal Haplotype" which is extremely rare outside Jewish populations, and even within Jewish populations is mainly only found in Cohanim. They also said that by using more markers and a more restrictive definition, the estimated age of the Cohanim lineage is lower than the estimates of Tofanelli 2009, and it is consistent with a common ancestor at the approximate time of founding of the priesthood which is the source of Cohen surnames.

J-L222.2

J-L222.1 is found in Saudi Arabia & Sudan as well as in North Africa (Eddali 2013).

Phylogenetics

In Y-chromosome phylogenetics, subclades are the branches of haplogroups. These subclades are also defined by single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) or unique event polymorphisms (UEPs).

Phylogenetic history

Prior to 2002, there were in academic literature at least seven naming systems for the Y-Chromosome Phylogenetic tree. This led to considerable confusion. In 2002, the major research groups came together and formed the Y-Chromosome Consortium (YCC). They published a joint paper that created a single new tree that all agreed to use. Later, a group of citizen scientists with an interest in population genetics and genetic genealogy formed a working group to create an amateur tree aiming at being above all timely. The table below brings together all of these works at the point of the landmark 2002 YCC Tree. This allows a researcher reviewing older published literature to quickly move between nomenclatures.

| YCC 2002/2008 (Shorthand) | (α) | (β) | (γ) | (δ) | (ε) | (ζ) | (η) | YCC 2002 (Longhand) | YCC 2005 (Longhand) | YCC 2008 (Longhand) | YCC 2010r (Longhand) | ISOGG 2006 | ISOGG 2007 | ISOGG 2008 | ISOGG 2009 | ISOGG 2010 | ISOGG 2011 | ISOGG 2012 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| J-12f2a | 9 | VI | Med | 23 | Eu10 | H4 | B | J* | J | J | J | - | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| J-M62 | 9 | VI | Med | 23 | Eu10 | H4 | B | J1 | J1a | J1a | J1a | - | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| J-M172 | 9 | VI | Med | 24 | Eu9 | H4 | B | J2* | J2 | J2 | J2 | - | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| J-M47 | 9 | VI | Med | 24 | Eu9 | H4 | B | J2a | J2a | J2a1 | J2a4a | - | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| J-M68 | 9 | VI | Med | 24 | Eu9 | H4 | B | J2b | J2b | J2a3 | J2a4c | - | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| J-M137 | 9 | VI | Med | 24 | Eu9 | H4 | B | J2c | J2c | J2a4 | J2a4h2a1 | - | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| J-M158 | 9 | VI | Med | 24 | Eu9 | H4 | B | J2d | J2d | J2a5 | J2a4h1 | - | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| J-M12 | 9 | VI | Med | 24 | Eu9 | H4 | B | J2e* | J2e | J2b | J2b | - | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| J-M102 | 9 | VI | Med | 24 | Eu9 | H4 | B | J2e1* | J2e1 | J2b | J2b | - | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| J-M99 | 9 | VI | Med | 24 | Eu9 | H4 | B | J2e1a | J2e1a | J2b2a | J2b2a | - | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| J-M67 | 9 | VI | Med | 24 | Eu9 | H4 | B | J2f* | J2f | J2a2 | J2a4b | - | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| J-M92 | 9 | VI | Med | 24 | Eu9 | H4 | B | J2f1 | J2f1 | J2a2a | J2a4b1 | - | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| J-M163 | 9 | VI | Med | 24 | Eu9 | H4 | B | J2f2 | J2f2 | J2a2b | J2a4b2 | - | - | - | - | - | - | - |

Original research publications

The following research teams per their publications were represented in the creation of the YCC tree.

Discussion

This section is empty. You can help by adding to it. (January 2013) |

Phylogenetic trees

There are several confirmed and proposed phylogenetic trees available for haplogroup J-M267. The scientifically accepted one is the Y-Chromosome Consortium (YCC) one published in Karafet 2008 and subsequently updated. A draft tree that shows emerging science is provided by Thomas Krahn at the Genomic Research Center in Houston, Texas. The International Society of Genetic Genealogy (ISOGG) also provides an amateur tree.

The Genomic Research Center draft tree

This is Thomas Krahn at the Genomic Research Center's draft tree Proposed Tree for haplogroup J-M267 (Krahn & FTDNA 2013). For brevity, only the first three levels of subclades are shown.

- M267, L255, L321, L765, L814, L827, L1030

- M62

- M365.1

- L136, L572, L620

- M390

- P56

- P58, L815, L828

- M368.1

- M369

- L92.1, L93

- L147.1, L858, L862, Z643

- L386

- L817, L818

- L860

- L256

- Z1828, Z1829, Z1832, Z1833, Z1834, Z1836, Z1839, Z1840, Z1841, Z1843, Z1844

- Z1842

- L972

The Y-Chromosome Consortium tree

This is the official scientific tree produced by the Y-Chromosome Consortium (YCC). The last major update was in 2008 (Karafet 2008). Subsequent updates have been quarterly and biannual. The current version is a revision of the 2010 update.[1]

This section needs expansion. You can help by adding to it. (January 2013) |

The ISOGG tree

This section needs to be updated. (January 2013) |

Below are the subclades of Haplogroup J-P209 with their defining mutation, according to the ISOGG tree (as of March 2010). Note that the descent-based identifiers may be subject to change, as new SNPs are discovered that augment and further refine the tree. For brevity, only the first three levels of subclades are shown.

See also

Genetics

Y-DNA J Subclades

Y-DNA Backbone Tree

References

- ^ "Y-DNA Haplotree". Family Tree DNA uses the Y-Chromosome Consortium tree and posts it on their website.

Footnotes

Works Cited

Journals

- Moran, CN (2004). "Y chromosome haplogroups of elite Ethiopian endurance runners". Hum Genet. 115 (6): 492–7. doi:10.1007/s00439-004-1202-y. PMID 15503146.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help); Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: ref duplicates default (link) - Abu-Amero, Khaled K; Hellani, Ali; González, Ana M; Larruga, Jose M; Cabrera, Vicente M; Underhill, Peter A (2009). "Saudi Arabian Y-Chromosome diversity and its relationship with nearby regions". BMC Genetics. 10: 59. doi:10.1186/1471-2156-10-59. PMC 2759955. PMID 19772609.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: unflagged free DOI (link) - Alvarez, Luis; Santos, Cristina; Montiel, Rafael; Caeiro, Blazquez; Baali, Abdellatif; Dugoujon, Jean-Michel; Aluja, Maria Pilar (2009). "Y-chromosome variation in South Iberia: Insights into the North African contribution". American Journal of Human Biology. 21 (3): 407–9. doi:10.1002/ajhb.20888. PMID 19213004.

{{cite journal}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Arredi, B; Poloni, E; Paracchini, S; Zerjal, T; Fathallah, D; Makrelouf, M; Pascali, V; Novelletto, A; Tylersmith, C (2004). "A Predominantly Neolithic Origin for Y-Chromosomal DNA Variation in North Africa". The American Journal of Human Genetics. 75 (2): 338–45. doi:10.1086/423147. PMC 1216069. PMID 15202071.

{{cite journal}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Balanovsky, O.; Dibirova, K.; Dybo, A.; Mudrak, O.; Frolova, S.; Pocheshkhova, E.; Haber, M.; Platt, D.; Schurr, T. (2011). "Parallel Evolution of Genes and Languages in the Caucasus Region". Molecular Biology and Evolution. 28 (10): 2905–20. doi:10.1093/molbev/msr126. PMC 3355373. PMID 21571925.

{{cite journal}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Battaglia, Vincenza; Fornarino, Simona; Al-Zahery, Nadia; Olivieri, Anna; Pala, Maria; Myres, Natalie M; King, Roy J; Rootsi, Siiri; Marjanovic, Damir (2008). "Y-chromosomal evidence of the cultural diffusion of agriculture in southeast Europe". European Journal of Human Genetics. 17 (6): 820–30. doi:10.1038/ejhg.2008.249. PMC 2947100. PMID 19107149.

{{cite journal}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Cadenas, Alicia M; Zhivotovsky, Lev A; Cavalli-Sforza, Luca L; Underhill, Peter A; Herrera, Rene J (2007). "Y-chromosome diversity characterizes the Gulf of Oman". European Journal of Human Genetics. 16 (3): 374–86. doi:10.1038/sj.ejhg.5201934. PMID 17928816.

{{cite journal}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Cann, H. M. (2002). "A Human Genome Diversity Cell Line Panel". Science. 296 (5566): 261b. doi:10.1126/science.296.5566.261b. PMID 11954565.

{{cite journal}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Capelli, Cristian; Onofri, Valerio; Brisighelli, Francesca; Boschi, Ilaria; Scarnicci, Francesca; Masullo, Mara; Ferri, Gianmarco; Tofanelli, Sergio; Tagliabracci, Adriano (2009). "Moors and Saracens in Europe: Estimating the medieval North African male legacy in southern Europe". European Journal of Human Genetics. 17 (6): 848–52. doi:10.1038/ejhg.2008.258. PMC 2947089. PMID 19156170.

{{cite journal}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Chiaroni, J; King, Roy J; Underhill, Peter A (2008). "Correlation of annual precipitation with human Y-chromosome diversity and the emergence of Neolithic agricultural and pastoral economies in the Fertile Crescent". 82 (316): 281.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help); Text "ANTIQUITY-OXFORD" ignored (help) - Chiaroni, Jacques; King, Roy J; Myres, Natalie M; Henn, Brenna M; Ducourneau, Axel; Mitchell, Michael J; Boetsch, Gilles; Sheikha, Issa; Lin, Alice A (2009). "The emergence of Y-chromosome haplogroup J1e among Arabic-speaking populations". European Journal of Human Genetics. 18 (3): 348–53. doi:10.1038/ejhg.2009.166. PMC 2987219. PMID 19826455.

{{cite journal}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Cinnioglu, Cengiz; King, Roy; Kivisild, Toomas; Kalfoglu, Ersi; Atasoy, Sevil; Cavalleri, Gianpiero L; Lillie, Anita S.; Roseman, Charles C; Lin, Alice A (2004). "Excavating Y-chromosome haplotype strata in Anatolia". Human Genetics. 114 (2): 127–48. doi:10.1007/s00439-003-1031-4. PMID 14586639.

{{cite journal}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Di Gaetano, Cornelia; Cerutti, Nicoletta; Crobu, Francesca; Robino, Carlo; Inturri, Serena; Gino, Sarah; Guarrera, Simonetta; Underhill, Peter A; King, Roy J (2008). "Differential Greek and northern African migrations to Sicily are supported by genetic evidence from the Y chromosome". European Journal of Human Genetics. 17 (1): 91–9. doi:10.1038/ejhg.2008.120. PMC 2985948. PMID 18685561.

{{cite journal}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - El-Sibai, Mirvat; Platt, Daniel E.; Haber, Marc; Xue, Yali; Youhanna, Sonia C.; Wells, R. Spencer; Izaabel, Hassan; Sanyoura, May F.; Harmanani, Haidar (2009). "Geographical Structure of the Y-chromosomal Genetic Landscape of the Levant: A coastal-inland contrast". Annals of Human Genetics. 73 (6): 568–81. doi:10.1111/j.1469-1809.2009.00538.x. PMID 19686289.

{{cite journal}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Ennafaa, Hajer; Fregel, Rosa; Khodjet-El-Khil, Houssein; González, Ana M; Mahmoudi, Hejer Abdallah El; Cabrera, Vicente M; Larruga, José M; Benammar-Elgaaïed, Amel (2011). "Mitochondrial DNA and Y-chromosome microstructure in Tunisia". Journal of Human Genetics. 56 (10): 734–41. doi:10.1038/jhg.2011.92. PMID 21833004.

{{cite journal}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Fadhlaoui-Zid, Karima; Martinez-Cruz, Begoña; Khodjet-El-Khil, Houssein; Mendizabal, Isabel; Benammar-Elgaaied, Amel; Comas, David (2011). "Genetic structure of Tunisian ethnic groups revealed by paternal lineages". American Journal of Physical Anthropology. 146 (2): 271–80. doi:10.1002/ajpa.21581. PMID 21915847.

{{cite journal}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Flores, Carlos; Maca-Meyer, Nicole; Larruga, Jose M.; Cabrera, Vicente M.; Karadsheh, Naif; Gonzalez, Ana M. (2005). "Isolates in a corridor of migrations: A high-resolution analysis of Y-chromosome variation in Jordan". Journal of Human Genetics. 50 (9): 435–41. doi:10.1007/s10038-005-0274-4. PMID 16142507.

{{cite journal}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Fregel, Rosa; Gomes, Verónica; Gusmão, Leonor; González, Ana M; Cabrera, Vicente M; Amorim, António; Larruga, Jose M (2009). "Demographic history of Canary Islands male gene-pool: Replacement of native lineages by European". BMC Evolutionary Biology. 9: 181. doi:10.1186/1471-2148-9-181. PMC 2728732. PMID 19650893.

{{cite journal}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help)CS1 maint: unflagged free DOI (link) - Di Giacomo, F.; Luca, F.; Popa, L. O.; Akar, N.; Anagnou, N.; Banyko, J.; Brdicka, R.; Barbujani, G.; Papola, F. (2004). "Y chromosomal haplogroup J as a signature of the post-neolithic colonization of Europe". Human Genetics. 115 (5): 357–71. doi:10.1007/s00439-004-1168-9. PMID 15322918.

{{cite journal}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Goncalves, Rita; Freitas, Ana; Branco, Marta; Rosa, Alexandra; Fernandes, Ana T.; Zhivotovsky, Lev A.; Underhill, Peter A.; Kivisild, Toomas; Brehm, Antonio (2005). "Y-chromosome Lineages from Portugal, Madeira and Acores Record Elements of Sephardim and Berber Ancestry". Annals of Human Genetics. 69 (4): 443–54. doi:10.1111/j.1529-8817.2005.00161.x. PMID 15996172.

{{cite journal}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) Also http://wysinger.homestead.com/portugal.pdf - Hammer, Michael F.; Behar, Doron M.; Karafet, Tatiana M.; Mendez, Fernando L.; Hallmark, Brian; Erez, Tamar; Zhivotovsky, Lev A.; Rosset, Saharon; Skorecki, Karl (2009). "Extended Y chromosome haplotypes resolve multiple and unique lineages of the Jewish priesthood". Human Genetics. 126 (5): 707–17. doi:10.1007/s00439-009-0727-5. PMC 2771134. PMID 19669163.

{{cite journal}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC2771134/ or http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC2771134/pdf/439_2009_Article_727.pdf - Hassan, Hisham Y.; Underhill, Peter A.; Cavalli-Sforza, Luca L.; Ibrahim, Muntaser E. (2008). "Y-chromosome variation among Sudanese: Restricted gene flow, concordance with language, geography, and history". American Journal of Physical Anthropology. 137 (3): 316–23. doi:10.1002/ajpa.20876. PMID 18618658.

{{cite journal}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Karafet, T. M.; Mendez, F. L.; Meilerman, M. B.; Underhill, Peter A.; Zegura, S. L.; Hammer, M. F. (2008). "New binary polymorphisms reshape and increase resolution of the human Y chromosomal haplogroup tree". Genome Research. 18 (5): 830–8. doi:10.1101/gr.7172008. PMC 2336805. PMID 18385274.

{{cite journal}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) Published online April 2, 2008. See also Supplementary Material. - King, R; Underhill, Peter A (2002). "Congruent distribution of Neolithic painted pottery and ceramic figurines with Y-chromosome lineages". ANTIQUITY-OXFORD. 76 (293): 707–714.

- King, R. J.; Özcan, S. S.; Carter, T.; Kalfoğlu, E.; Atasoy, S.; Triantaphyllidis, C.; Kouvatsi, A.; Lin, A. A.; Chow, C-E. T. (2008). "Differential Y-chromosome Anatolian Influences on the Greek and Cretan Neolithic". Annals of Human Genetics. 72 (2): 205–14. doi:10.1111/j.1469-1809.2007.00414.x. PMID 18269686.

{{cite journal}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Kujanová, Martina; Pereira, Luísa; Fernandes, Verónica; Pereira, Joana B.; čErný, Viktor (2009). "Near Eastern Neolithic genetic input in a small oasis of the Egyptian Western Desert". American Journal of Physical Anthropology. 140 (2): 336–46. doi:10.1002/ajpa.21078. PMID 19425100.

{{cite journal}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Luis, J; Rowold, D; Regueiro, M; Caeiro, B; Cinnioglu, C; Roseman, C; Underhill, P; Cavallisforza, L; Herrera, R (2004). "The Levant versus the Horn of Africa: Evidence for Bidirectional Corridors of Human Migrations". The American Journal of Human Genetics. 74 (3): 532–44. doi:10.1086/382286. PMC 1182266. PMID 14973781.

{{cite journal}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help). (Also see Errata) - Msaidie, Said; Ducourneau, Axel; Boetsch, Gilles; Longepied, Guy; Papa, Kassim; Allibert, Claude; Yahaya, Ali Ahmed; Chiaroni, Jacques; Mitchell, Michael J (2010). "Genetic diversity on the Comoros Islands shows early seafaring as major determinant of human biocultural evolution in the Western Indian Ocean". European Journal of Human Genetics. 19 (1): 89–94. doi:10.1038/ejhg.2010.128. PMC 3039498. PMID 20700146.

{{cite journal}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Nebel, A; Filon, D; Weiss, DA; Weale, M; Faerman, M; Oppenheim, A; Thomas, MG (2000). "High-resolution Y chromosome haplotypes of Israeli and Palestinian Arabs reveal geographic substructure and substantial overlap with haplotypes of Jews". Hum Genet. 107 (6): 630–41. doi:10.1007/s004390000426. PMID 11153918.

{{cite journal}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Nebel, A; Filon, D; Brinkmann, B; Majumder, P; Faerman, M; Oppenheim, A (2001). "The Y Chromosome Pool of Jews as Part of the Genetic Landscape of the Middle East". The American Journal of Human Genetics. 69 (5): 1095–112. doi:10.1086/324070. PMC 1274378. PMID 11573163.

{{cite journal}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Nebel, A (2002). "Genetic Evidence for the Expansion of Arabian Tribes into the Southern Levant and North Africa". The American Journal of Human Genetics. 70 (6): 1594–6. doi:10.1086/340669. PMC 379148. PMID 11992266.

- Nogueiro (2009). "Phylogeographic analysis of paternal lineages in NE Portuguese Jewish communities". American Journal of Physical Anthropology. 141 (3): NA. doi:10.1002/ajpa.21154. PMID 19918998.

{{cite journal}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Onofri, Valerio; Alessandrini, Federica; Turchi, Chiara; Pesaresi, Mauro; Tagliabracci, Adriano (2008). "Y-chromosome markers distribution in Northern Africa: High-resolution SNP and STR analysis in Tunisia and Morocco populations". Forensic Science International: Genetics Supplement Series. 1: 235. doi:10.1016/j.fsigss.2007.10.173.

{{cite journal}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Ottoni, Claudio; Larmuseau, Maarten H.D.; Vanderheyden, Nancy; Martínez-Labarga, Cristina; Primativo, Giuseppina; Biondi, Gianfranco; Decorte, Ronny; Rickards, Olga (2011). "Deep into the roots of the Libyan Tuareg: A genetic survey of their paternal heritage". American Journal of Physical Anthropology. 145 (1): 118–24. doi:10.1002/ajpa.21473. PMID 21312181.

{{cite journal}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Regueiro, M.; Cadenas, A.M.; Gayden, T.; Underhill, P.A.; Herrera, R.J. (2006). "Iran: Tricontinental Nexus for Y-Chromosome Driven Migration". Human Heredity. 61 (3): 132–43. doi:10.1159/000093774. PMID 16770078.

{{cite journal}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Repping, S; Van Daalen, SK; Brown, LG; Korver, Cindy M; Lange, Julian; Marszalek, Janet D; Pyntikova, Tatyana; Van Der Veen, Fulco; Skaletsky, Helen (2006). "High mutation rates have driven extensive structural polymorphism among human Y chromosomes". Nat Genet. 38 (38): 463–467. doi:10.1038/ng1754.

{{cite journal}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Robino, C.; Crobu, F.; Gaetano, C.; Bekada, A.; Benhamamouch, S.; Cerutti, N.; Piazza, A.; Inturri, S.; Torre, C. (2007). "Analysis of Y-chromosomal SNP haplogroups and STR haplotypes in an Algerian population sample". International Journal of Legal Medicine. 122 (3): 251–5. doi:10.1007/s00414-007-0203-5. PMID 17909833.

{{cite journal}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Semino, Ornella; Magri, Chiara; Benuzzi, Giorgia; Lin, Alice A.; Al-Zahery, Nadia; Battaglia, Vincenza; MacCioni, Liliana; Triantaphyllidis, Costas; Shen, Peidong (2004). "Origin, Diffusion, and Differentiation of Y-Chromosome Haplogroups E and J: Inferences on the Neolithization of Europe and Later Migratory Events in the Mediterranean Area". The American Journal of Human Genetics. 74 (5): 1023–34. doi:10.1086/386295. PMC 1181965. PMID 15069642.

{{cite journal}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Sengupta, Sanghamitra; Zhivotovsky, Lev A.; King, Roy; Mehdi, S.Q.; Edmonds, Christopher A.; Chow, Cheryl-Emiliane T.; Lin, Alice A.; Mitra, Mitashree; Sil, Samir K. (2006). "Polarity and Temporality of High-Resolution Y-Chromosome Distributions in India Identify Both Indigenous and Exogenous Expansions and Reveal Minor Genetic Influence of Central Asian Pastoralists". The American Journal of Human Genetics. 78 (2): 202–21. doi:10.1086/499411. PMC 1380230. PMID 16400607.

{{cite journal}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Shen, Peidong; Lavi, Tal; Kivisild, Toomas; Chou, Vivian; Sengun, Deniz; Gefel, Dov; Shpirer, Issac; Woolf, Eilon; Hillel, Jossi (2004). "Reconstruction of patrilineages and matrilineages of Samaritans and other Israeli populations from Y-Chromosome and mitochondrial DNA sequence Variation". Human Mutation. 24 (3): 248–60. doi:10.1002/humu.20077. PMID 15300852.

{{cite journal}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Shlush, Liran I.; Behar, Doron M.; Yudkovsky, Guennady; Templeton, Alan; Hadid, Yarin; Basis, Fuad; Hammer, Michael; Itzkovitz, Shalev; Skorecki, Karl (2008). Gemmell, Neil John (ed.). "The Druze: A Population Genetic Refugium of the Near East". PLoS ONE. 3 (5): e2105. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0002105. PMC 2324201. PMID 18461126.

{{cite journal}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help)CS1 maint: unflagged free DOI (link) - Tofanelli, Sergio; Ferri, Gianmarco; Bulayeva, Kazima; Caciagli, Laura; Onofri, Valerio; Taglioli, Luca; Bulayev, Oleg; Boschi, Ilaria; Alù, Milena (2009). "J1-M267 Y lineage marks climate-driven pre-historical human displacements". European Journal of Human Genetics. 17 (11): 1520–4. doi:10.1038/ejhg.2009.58. PMC 2986692. PMID 19367321.

{{cite journal}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Zalloua, Pierre A.; Xue, Yali; Khalife, Jade; Makhoul, Nadine; Debiane, Labib; Platt, Daniel E.; Royyuru, Ajay K.; Herrera, Rene J.; Hernanz, David F. Soria (2008). "Y-Chromosomal Diversity in Lebanon is Structured by Recent Historical Events". The American Journal of Human Genetics. 82 (4): 873–82. doi:10.1016/j.ajhg.2008.01.020. PMC 2427286. PMID 18374297.

{{cite journal}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Zalloua, Pierre A.; Platt, Daniel E.; El Sibai, Mirvat; Khalife, Jade; Makhoul, Nadine; Haber, Marc; Xue, Yali; Izaabel, Hassan; Bosch, Elena (2008). "Identifying Genetic Traces of Historical Expansions: Phoenician Footprints in the Mediterranean". The American Journal of Human Genetics. 83 (5): 633–42. doi:10.1016/j.ajhg.2008.10.012. PMC 2668035. PMID 18976729.

{{cite journal}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help)

Websites

Haplogroups/Phylogeny

- ISOGG (2013). "Y-DNA Haplogroup J and its Subclades". International Society of Genetic Genealogists "ISOGG".

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) Ongoing Corrections/Additions by citizen scientists.

Haplotype/SNP research Projects. See also Y-DNA haplogroup projects (ISOGG Wiki)

- Schrack; Janzen; Rottensteiner; Ricci; Mas (2013). "Y-DNA J Haplogroup Project". Family Tree DNA. This is an ongoing research project by citizen scientists. Over 2300 members.

- Givargidze; Hrechdakian (2013). "J1* Y-DNA Project". Family Tree DNA. This is an ongoing research project by citizen scientists. Over 150 members.

- Al Haddad (2013). "J1c3 (J-L147)". Family Tree DNA. This is an ongoing research project by citizen scientists. Over 550 members.

- Cone; Al Gazzah; Sanders (2013). "J-M172 Y-DNA Project (J2)". Family Tree DNA. This is an ongoing research project by citizen scientists. Over 1050 members.

- Aburto; Katz; Al Gazzah; Janzen (2013). "J-L24-Y-DNA Haplogroup Project (J2a1h)". Family Tree DNA. This is an ongoing research project by citizen scientists. Over 450 members.

Haplogroup-Specific Ethnic/Geographical Group Projects

- Eddali (2013). "Arab Tribes". Family Tree DNA. This is an ongoing research project by citizen scientists. Over 950 J members.

- Al Gazzah (2013). "J2-Middle East Project مشروع سلالة ج2 في العالم العربي والشرق الأوسط". Family Tree DNA. This is an ongoing research project by citizen scientists. Over 400 members.

Further reading

- Behar, Doron M.; Thomas, Mark G.; Skorecki, Karl; Hammer, Michael F.; Bulygina, Ekaterina; Rosengarten, Dror; Jones, Abigail L.; Held, Karen; Moses, Vivian (2003). "Multiple Origins of Ashkenazi Levites: Y Chromosome Evidence for Both Near Eastern and European Ancestries". The American Journal of Human Genetics. 73 (4): 768–79. doi:10.1086/378506. PMC 1180600. PMID 13680527.

{{cite journal}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help). Also at http://www.ucl.ac.uk/tcga/tcgapdf/Behar-AJHG-03.pdf and http://www.familytreedna.com/pdf/400971.pdf - Behar, Doron M.; Garrigan, Daniel; Kaplan, Matthew E.; Mobasher, Zahra; Rosengarten, Dror; Karafet, Tatiana M.; Quintana-Murci, Lluis; Ostrer, Harry; Skorecki, Karl (2004). "Contrasting patterns of Y chromosome variation in Ashkenazi Jewish and host non-Jewish European populations". Human Genetics. 114 (4): 354–65. doi:10.1007/s00439-003-1073-7. PMID 14740294.

{{cite journal}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Consortium, T. Y C. (2002). "A Nomenclature System for the Tree of Human Y-Chromosomal Binary Haplogroups". Genome Research. 12 (2): 339–48. doi:10.1101/gr.217602. PMC 155271. PMID 11827954.

{{cite journal}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Firasat, Sadaf; Khaliq, Shagufta; Mohyuddin, Aisha; Papaioannou, Myrto; Tyler-Smith, Chris; Underhill, Peter A; Ayub, Qasim (2006). "Y-chromosomal evidence for a limited Greek contribution to the Pathan population of Pakistan". European Journal of Human Genetics. 15 (1): 121–6. doi:10.1038/sj.ejhg.5201726. PMC 2588664. PMID 17047675.

{{cite journal}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Flores, Carlos; Maca-Meyer, Nicole; González, Ana M; Oefner, Peter J; Shen, Peidong; Pérez, Jose A; Rojas, Antonio; Larruga, Jose M; Underhill, Peter A (2004). "Reduced genetic structure of the Iberian peninsula revealed by Y-chromosome analysis: Implications for population demography". European Journal of Human Genetics. 12 (10): 855–63. doi:10.1038/sj.ejhg.5201225. PMID 15280900.

{{cite journal}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Semino, O.; Passarino, G; Oefner, PJ; Lin, AA; Arbuzova, S; Beckman, LE; De Benedictis, G; Francalacci, P; Kouvatsi, A (2000). "The Genetic Legacy of Paleolithic Homo sapiens sapiens in Extant Europeans: A Y Chromosome Perspective". Science. 290 (5494): 1155–9. doi:10.1126/science.290.5494.1155. PMID 11073453.

{{cite journal}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help)

Phylogenetic Notes

- ^ This table shows the historic names for J-M267 and its earlier discovered and named subclade J-M62 in published peer reviewed literature.

YCC 2002/2008 (Shorthand) J-M267 J-M62 Jobling and Tyler-Smith 2000 - 9 Underhill 2000 - VI Hammer 2001 - Med Karafet 2001 - 23 Semino 2000 - Eu10 Su 1999 - H4 Capelli 2001 - B YCC 2002 (Longhand) - J1 YCC 2005 (Longhand) J1 J1a YCC 2008 (Longhand) J1 J1a YCC 2010r (Longhand) J1 J1a - ^ a b This table shows the historic names for J-P209 (AKA J-12f2.1 or J-M304) in published peer reviewed literature. Note that in Semino 2000 Eu09 is a subclade of Eu10 and in Karafet 2001 24 is a subclade of 23.

YCC 2002/2008 (Shorthand) J-P209

(AKA J-12f2.1 or J-M304)Jobling and Tyler-Smith 2000 9 Underhill 2000 VI Hammer 2001 Med Karafet 2001 23 Semino 2000 Eu10 Su 1999 H4 Capelli 2001 B YCC 2002 (Longhand) J* YCC 2005 (Longhand) J YCC 2008 (Longhand) J YCC 2010r (Longhand) J