Hidden Armenians

Hidden Armenians (Turkish: Gizli Ermeniler) or crypto-Armenians (Armenian: ծպտեալ հայեր tsptyal hayer; Turkish: Kripto Ermeniler)[1] is an "umbrella term to describe Turkish people of full or partial ethnic Armenian origin who generally conceal their Armenian identity from wider Turkish society."[2] They are mostly descendants of Ottoman Armenians who, at least outwardly, were Islamized (and turkified or kurdified) "under the threat of physical extermination" during the Armenian Genocide.[3][better source needed]

Turkish journalist Erhan Başyurt[a] describes hidden Armenians as "families (and in some cases, entire villages or neighbourhoods) [...] who converted to Islam to escape the deportations and death marches [of 1915], but continued their hidden lives as Armenians, marrying among themselves and, in some cases, clandestinely reverting to Christianity."[4] According to the European Commission 2012 report on Turkey, a "number of crypto-Armenians have started to use their original names and religion."[5] The Economist suggests that the number of Turks who reveal their Armenian background is growing.[6]

History

Background

The western parts of the Armenian Highlands, the traditional homeland of the Armenian people, came under Ottoman (Turkish) control in the 16th century.[7] Armenians remained an overwhelming majority of the area's population until the 17th century, however, their number gradually decreased and by the early 20th century they constituted up to 38% of the population of Western Armenia, designed at the time as the Six vilayets. Turks and Kurds made up a significant part of the population.[8]

Armenian Genocide

In 1915 and the following years, the Armenians living in their ancestral lands in the Ottoman Empire were systematically exterminated by the Young Turk government in the Armenian Genocide. During the genocide, between 100,000 and 200,000 Armenian women were taken into harems by Muslim husbands and children were converted, forced into slavery, or kidnapped and raised as Turks or Kurds.[9][10] When relief workers and surviving Armenians started to search for and claim back these Armenian orphans after World War I, only a small percentage were found and reunited, while many others continued to live as Muslims. Additionally, there were cases of entire families converting to Islam to survive the genocide.[11]

Republican period

"After converting to Islam, many of the crypto-Armenians said they still faced unfair treatment: their land was often confiscated, the men were humiliated with "circumcision checks" in the army and some were tortured."[12] Between the 1930s and 1980s, the Turkish government conducted a secret investigation of hidden Armenians.[13]

The term "Crypto-Armenians" appears as early as 1956.[14]

Recent developments

In 2010, Mass was held at Akdamar church for the first time in 95 years. Although the church was reopened as a museum in 2007, after a million dollar restoration, prayers were not allowed until 2010.[15] In September 2010, 2,000 Armenians attended a mass at Akdamar church.[16]

When the Surp Giragos Church was reopened in 2011, dozens of Armenians who had been raised Muslim participated in a baptism ceremony at the restored Church. The names of those who participated in the baptism ceremony, conducted by Deputy Patriarch Archbishop Aram Ateşyan, were not released publicly for security reasons. Turkish-Armenians who wish to convert must first file for a formal "change of religion" at court. They then go to the Church where they learn about the foundational teachings of the Christian faith. When it is decided that the applicant has understood these teachings, they are permitted to prepare for the baptism ceremony.[17][18]

In May 2015, 12 Armenians from Tunceli were baptized.[19] The twelve Armenians were baptized together in a collective ceremony after a six month education about Christian beliefs.[20]

In 2009, the British MP Bob Spink tabled an early day motion entitled "Independent Inquiry into The Armenian Genocide" that stated that the House of Commons "is concerned about the welfare of thousands of Crypto-Armenians in Turkey."[21]

Number

Various scholars and authors have estimated the number of individuals of full or partial Armenian descent living in Turkey. The range of the estimates is great due to different criteria used. Most of these numbers do not make a distinction between hidden Armenians and Islamized Armenians. According to journalist Erhan Başyurt the main difference between the two groups is their self-identity. Islamized Armenian, in his words, are "children women who were saved by Muslim families and have continued their lives among them", while hidden Armenians "continued their hidden lives as Armenians."[4]

| Number | Author | Description | Year |

|---|---|---|---|

| 30,000–40,000 | Tessa Hofmann, German scholar of Armenian studies | "Muslim 'crypto-Armenians' ... who have adapted to the Kurdish or Turkish majority" | 2002[22] |

| 100,000 | Mesrob II, Armenian Patriarch of Constantinople | "at least 100,000 Armenian converts to Islam" | 2007[23] |

| 100,000 | Erhan Başyurt, Turkish journalist | additional 40,000 to 60,000 Islamized Armenians | 2006[4] |

| 100,000 | Salim Cöhce, History Professor at the İnönü University | 2005[24] | |

| 300,000 | Hrant Dink, Turkish-Armenian journalist | 2005[24] | |

| 300,000 | Yervand Baret Manuk, Turkish-Armenian Armenologist | additional 1,000,000 to 2,000,000 Islamized Armenians | 2010[25] |

| 500,000 | Yusuf Halaçoğlu, Turkish historian | 2009[26][27] | |

| 700,000 | Karen Khanlaryan, Iranian Armenian journalist and MP | 700,000 hidden Armenians and 1,300,000 Islamized Armenians | 2005[3] |

| 3,000,000 | Haykazun Alvrtsyan, Armenian researcher | "In Germany alone, there were 300,000 Muslim Armenians. He insisted that today in the Eastern part of Turkey, in various areas of historic Armenia there live at least 2.5 million Muslim Armenians, half of which are hiding." | 2014[28] |

| 3,000,000–5,000,000 | Aziz Dagcı, the President of the NGO "Union of Social Solidarity and Culture for Bitlis, Batman, Van, Mush and Sasun Armenians" |

Islamized Armenians | 2011[29][30] |

| 4,000,000–5,000,000 | Sarkis Seropyan, the editor of the Armenian section of Agos | Islamized Armenians, more than half of which "confess that their ancestors have been Armenian" | 2013[31] |

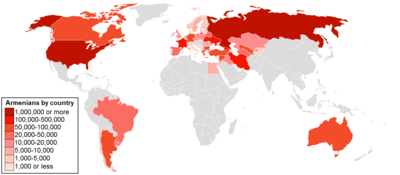

Distribution

Most Crypto-Armenians reside in eastern provinces of Turkey, where the pre-genocide Armenian population was concentrated.[32][33]

Tunceli

Dersim Armenians

Through the 20th century, an unknown number of Armenians living in the mountainous region of Tunceli (Dersim) had converted to Alevism.[34] During the Armenian Genocide, many of the Armenians in the region were saved by their Kurdish neighbors.[35] According to Mihran Prgiç Gültekin, the head of the Union of Dersim Armenians, around 75% of the population of Dersim are "converted Armenians."[36][37] He reported in 2012 that over 200 families in Tunceli have declared their Armenian descent, but others are afraid to do so.[36][38] In April 2013, Aram Ateşyan, the acting Armenian Patriarch of Constantinople, stated that 90% of Tunceli's population is of Armenian origin.[39]

Notable hidden Armenians

- Fethiye Çetin (b. 1950 in Maden, Elâzığ Province), lawyer, writer and human rights activist

- Ahmet Abakay (b. 1950 in Divriği), journalist[40]

- Yaşar Kurt (b. 1968), rock singer

- Ruhi Su (1912-1985), musician

See also

References

- Notes

- ^ Başyurt is the author of Armenian Adoptees: Hidden Lives (Ermeni Evlatlıklar, Saklı Kalmış Hayatlar), a book on Crypto-Armenians published in 2006.

- Citations

- ^ Ziflioğlu, Vercihan (24 June 2011). "Hidden Armenians in Turkey expose their identities". Hürriyet Daily News. Retrieved 13 November 2013.

- ^ Ziflioğlu, Vercihan (19 June 2012). "'Elective courses may be ice-breaker for all'". Hürriyet Daily News. Retrieved 24 June 2013.

- ^ a b Khanlaryan, Karen (29 September 2005). "The Armenian ethnoreligious elements in the Western Armenia". Noravank Foundation. Retrieved 16 June 2013.

- ^ a b c Altınay & Turkyilmaz 2011, p. 41.

- ^ "Commission Working Document Turkey 2012 Progress Repor" (PDF). European Commission. 10 October 2012. p. 24. Retrieved 21 October 2013.

- ^ "The cost of reconstruction". The Economist. 11 March 2010. Retrieved 24 June 2013.

Although today's inhabitants of Geben hesitate to call themselves Armenians, a growing number of "crypto-Armenians" (people forced to change identity) do just that.

- ^ West, Barbara A. (2009). Encyclopedia of the Peoples of Asia and Oceania. New York: Infobase Publishing. p. 56. ISBN 9781438119137.

- ^ Ghazarian, H. (1976). Hambardzumyan, Viktor (ed.). Soviet Armenian Encyclopedia Volume 2 (in Armenian). Yerevan: Armenian Encyclopedia Publishing. p. 43.

- ^ Goldhagen, Daniel Jonah (2010). Worse Than War: Genocide, Eliminationism, and the Ongoing Assault on Humanity (1st ed.). New York: PublicAffairs. p. 38. ISBN 9781586489007.

- ^ Naimark, Norman M. (2002). Fires of Hatred: Ethnic Cleansing in Twentieth-century Europe. Cambridge, Massachusetts: Harvard University Press. p. 42. ISBN 9780674009943.

- ^ Altınay & Turkyilmaz 2011, p. 25.

- ^ Cheviron, Nicholas (24 April 2013). "Turkey's Muslim Armenians come out of hiding". Agence France-Presse. Retrieved 24 June 2013.

- ^ Hur, Ayse (1 September 2008). "Turks cannot be without Armenians, Armenians cannot be without Turks!" (PDF). Taraf. Retrieved 24 June 2013.

- ^ "unknown". The Armenian Review. 9. Hairenik Association: 125. 1956.

Letters which have reached relatives in America at various times indicate that at least some of the Armenian Islamized persons are in fact "crypto-Armenians", in public completely loyal and nationalistic Turks, but privately waiting for the day...

{{cite journal}}: Cite uses generic title (help) - ^ "Armenians hold historic service in ancient Turkish church - CNN.com". Retrieved 30 December 2017.

- ^ "2,000 Armenians Flock to Mass in Ancient Restored Church". Times of Oman (Muscat, Oman). 9 September 2012. Retrieved 30 December 2017 – via HighBeam.

- ^ OCP (24 October 2011). "Armenians claim roots in Diyarbakır". Hurriyet. Retrieved 30 December 2017.

- ^ "Ermeni kimliğine dönenler artıyor [The return to Armenian identity increases]". Radikal (in Turkish). 20 November 2011. Retrieved 16 June 2013.

- ^ eakin (1 June 2015). "How some Armenians are reclaiming their Christian faith". Al-Monitor. Retrieved 30 December 2017.

- ^ "12 Dersimli Ermeni vaftizle kimliğine döndü". Agos. Retrieved 30 December 2017.

- ^ Spink, Bob (25 November 2009). "Independent Inquiry into The Armenian Genocide". Parliament of the United Kingdom. Retrieved 24 June 2013.

- ^ Hofmann, Tessa (October 2002). "Armenians in Turkey Today" (PDF). Forum of Armenian Associations in Europe. pp. 10–11. Retrieved 24 June 2013.

- ^ Reimann, Anna (1 June 2007). "Armenischer Patriarch in der Türkei: "Die Armenier sind wieder allein" [Armenian Patriarch in Turkey: "The Armenians are alone again"]". Spiegel Online (in German). Retrieved 16 June 2013.

Patriarch Mesrob II: Heute leben ungefähr 80.000 christliche Armenier in der Türkei. Mindestens 100.000 weitere Armenier seien zum Islam konvertiert.

- ^ a b Basyurt, Erhan (26 December 2005). "Anneannem bir Ermeni'ymiş! [My Grandmother is Armenian]". Aksiyon (in Turkish). Archived from the original on 10 November 2013. Retrieved 10 November 2013.

300 bin rakamının abartılı olduğunu düşünmüyorum. Bence daha da fazladır. Ama, bu konu maalesef akademik bir çabaya dönüşmemiş. Keşke akademisyen olsaydım ve sırf bu konu üzerinde bir çalışma yapsaydım.

{{cite news}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ ""Իսլամացուած եւ գաղտնի հայերը միատարր չեն", ըստ Երուանդ Մանուկի [Ervand Manuk: "The Islamized Armenians are not homogeneous"]". Aztag (in Armenian). 7 October 2010. Retrieved 24 June 2013.

Մահմետական հայերու համար 1–2 միլիոն, գաղտնի հայերու համար 300 հազարէն 1 միլիոն թիւերը կը տրուին: Բնականաբար այս թիւերը գիտական եւ ստոյգ չեն:

- ^ "500 Bi̇n Kri̇pto Ermeni̇ Var". Odatv (in Turkish). 23 September 2009. Retrieved 24 June 2013.

- ^ "Prof. Dr. Halaçoğlu: Ermeniler Anadolu'da 500 Bine Yakın Türk'ü Katletti" (in Turkish). Cihan News Agency. 2 March 2011. Retrieved 24 June 2013.

- ^ Mkrtchyan, Gayane (28 October 2014). "The "Armenian Question": Specialist says political changes bring chance for reclaiming ethnic roots for Armenians in Turkey". ArmeniaNow.

- ^ Danielyan, Diana (1 July 2011). "Հնարավո՞ր է արթացնել Թուրքիայի մուսուլմանացած հայերին [Is the awakening of Islamized Armenians in Turkey possible?]". Azg Daily. Retrieved 24 June 2013.

Դաղչը զարմանալի թիվ է մատնանշում. տարբեր հաշվարկների համաձայնՙ Թուրքիայում 3–5 մլն մուսուլմանացած հայեր կան:

- ^ Danielyan, Diana (1 July 2011). ""Azg": Is the awakening of Islamized Armenians in Turkey possible?". Hayern Aysor. Retrieved 24 June 2013.

Dagch says according to different calculations, there are 3–5 million Islamized Armenians in Turkey

- ^ "More than half of 4–5 million Islamized Armenians confess that their ancestors have been Armenian". Public Radio of Armenia. 5 November 2013. Retrieved 10 November 2013.

- ^ Söylemez, Haşim (27 August 2007). "Türkiye'de, Araplaşan binlerce Ermeni de var". Aksiyon (in Turkish). Archived from the original on 3 June 2013. Retrieved 16 June 2013.

{{cite news}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ Melkonyan, Ruben (27 September 2007). "Արաբացած հայեր Թուրքիայում [Arabized Armenians in Turkey]" (in Turkish). Noravank Foundation. Retrieved 16 June 2013.

- ^ "Armenian Elements in the Beliefs of the Kizilbash Kurds". İnternet Haber. 27 April 2013. Archived from the original on 24 March 2012. Retrieved 28 April 2013.

{{cite news}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ A. Davis, Leslie (1990). Blair, Susan K. (ed.). The slaughterhouse province: an American diplomat's report on the Armenian genocide, 1915–1917 (2. print. ed.). New Rochelle, New York: A.D. Caratzas. ISBN 9780892414581.

- ^ a b "Mihran Gultekin: Dersim Armenians Re-Discovering Their Ancestral Roots". Massis Post. Yerevan. 7 February 2011. Archived from the original on 28 January 2013. Retrieved 30 December 2012.

{{cite news}}: Unknown parameter|dead-url=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ Adamhasan, Ali (5 December 2011). "Dersimin Nobel adayları..." Adana Medya (in Turkish). Archived from the original on 16 January 2013. Retrieved 20 October 2013.

{{cite news}}: Unknown parameter|dead-url=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ "Dersim Armenians back to their roots". PanARMENIAN.Net. 7 February 2011. Retrieved 31 December 2012.

- ^ "Tunceli'nin yüzde 90'ı dönme Ermeni'dir". İnternet Haber (in Turkish). 27 April 2013. Retrieved 28 April 2013.

- ^ Ziflioglu, Vercihan. "My mother was Armenian, journalist group chair reveals". Hürriyet Daily News. Retrieved 14 October 2013.

Bibliography

- Melkonyan, Ruben (2008). "The Problem of Islamized Armenians in Turkey" (PDF). Yerevan: Noravank Foundation.

- Melkonyan, Ruben (2009). Իսլամացված հայերի խնդիրների շուրջ [On the Issues of Islamized Armenians] (in Armenian). Yerevan: Noravank Foundation.

- Altınay, Ayşe Gül; Turkyilmaz, Yektan (2011). "Unraveling layers of gendered silencing: Converted Armenian survivors of the 1915 catastrophe". In Singer, Amy; Neumann, Christoph K.; Somel, Selcuk Aksin (eds.). Untold Histories of the Middle East: Recovering Voices from the 19th and 20th Centuries. Abingdon, Oxon: Routledge. ISBN 9780203845363.

{{cite book}}:|journal=ignored (help); Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Altınay, Ayşe Gül; Çetin, Fethiye (2014). The Grandchildren: The Hidden Legacy of 'Lost' Armenians in Turkey. Transaction Publishers. ISBN 978-1412853910.