Holocaust trains

| The Holocaust trains | |

|---|---|

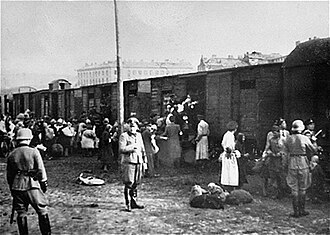

Polish Jews being loaded onto trains at Umschlagplatz of the Warsaw Ghetto, 1942. The site is preserved today as the Polish national monument | |

| Operation | |

| Period | 1941 – 1944 |

| Location | Nazi Germany, Occupied Poland; Belgium, Bulgaria, the Baltic states, Bessarabia, France, Greece, Hungary, Italy, Netherlands, Romania |

| Prisoner victims | |

| Total | 4,000,000 (mostly Jews)[1] |

| Destination | Transit ghettos, Nazi concentration camps, forced labour and extermination camps |

Holocaust trains were railway transports run by the Deutsche Reichsbahn national railway system under the strict supervision of the German Nazis and their allies, for the purpose of forcible deportation of the Jews, as well as other victims of the Holocaust, to the German Nazi concentration, forced labour, and extermination camps.[2][3]

Modern historians suggest that without the mass transportation of the railways, the scale of the "Final Solution" would not have been possible.[4] The extermination of people targeted in the "Final Solution" was dependent on two factors: the capacity of the death camps to gas the victims and "process" their bodies quickly enough, as well as the capacity of the railways to transport the condemned prisoners from the Ghettos in Nazi-occupied Europe and Jewish ghettos in German-occupied Poland to selected extermination sites. The most modern accurate numbers on the scale of the "Final Solution" still rely partly on shipping records of the German railways.[5][6]

Pre-war

The first mass deportation of Jews from Nazi Germany occurred in less than a year before the outbreak of war. It was the forcible eviction of German Jews with Polish citizenship fuelled by the Kristallnacht. Approximately 30,000 Jews were rounded up and sent via rail to refugee camps. In July 1938 both the United States and Britain at the Évian Conference in France refused to accept any more Jewish immigrants.[7] The British Government agreed to take in the shipment of children arranged by Nicholas Winton in Prague, Czechoslovakia, on the conditions that he pay the cost (via Czech travel agency Cedok) and arrange for the foster care. Winton managed to arrange for 669 children to get out on eight trains to London (a small group of 15 were flown out via Sweden). The ninth train was to leave Prague on 3 September 1939, the day Britain entered World War II. The train never left the station, and none of the 250 children on board were seen again. All European Jews trapped under the Nazi regime became the target of Hitler's "Final Solution to the Jewish Question".[8]

The role of railways in the Final Solution

Within various phases of the Holocaust, the trains were employed differently. At first, they were used to concentrate the Jewish populations in the ghettos, and often to transport them to forced labour and German concentration camps for the purpose of economic exploitation.[9][10] In 1939 for logistical reasons the Jewish communities in settlements without railway lines in occupied Poland were dissolved.[11] By the end of 1941, about 3.5 million Polish Jews had been segregated and ghettoised by the SS in a massive deportation action involving the use of freight trains.[12] Permanent ghettos had direct railway connections, because the food aid (paid by the Jews themselves) was completely dependent on the SS similar to all newly built labour camps.[13] Jews were legally banned from baking bread.[14] They were sealed off from the general public in hundreds of virtual prison-islands called Jüdischer Wohnbezirk or Wohngebiet der Juden. However, the new system was unsustainable. By the end of 1941, most ghettoised Jews had no savings left to pay the SS for further bulk food deliveries.[13] The quagmire was resolved at the Wannsee conference of 20 January 1942 near Berlin, where the "Final Solution" (die Endlösung der Judenfrage) was set in place.[15]

During the liquidation of the ghettos starting in 1942, the trains were used to transport the condemned populations to death camps. To implement the "Final Solution", the Nazis made their own Deutsche Reichsbahn an indispensable element of the mass extermination machine, wrote historian Raul Hilberg.[10] Although the prisoner trains took away valuable track space, they allowed for the mass scale and shortened duration over which the extermination needed to take place. The fully enclosed nature of the locked and windowless cattle wagons greatly reduced the number and skill of troops required to transport the condemned Jews to their destinations. The use of railroads enabled the Nazis to lie about the "resettlement program" and, at the same time, build and operate more efficient gassing facilities which required limited supervision.[16]

The Nazis disguised their "Final Solution" as the mass "resettlement to the east". The victims were told they were being taken to labour camps in Ukraine. In reality, from 1942 on for most Jews, deportations meant only death at either Bełżec, Chełmno, Sobibór, Majdanek, Treblinka, or Auschwitz-Birkenau. Some trains that had already transported goods to the Eastern front on their return carried human cargo bound for extermination camps.[17] The plan was being realized in the utmost secrecy. In late 1942 during a telephone conversation Hitler's private secretary Martin Bormann admonished Heinrich Himmler who was informing him about 50,000 Jews already exterminated in a concentration camp in Poland. "They were not exterminated – Bormann screamed – only evacuated, evacuated, evacuated!" and slammed down the phone, wrote Enghelberg.[1]

Scale of the need for mass transportation

Following the Wannsee Conference of 1942, the Nazis began to murder the Jews in large numbers at newly built death camps of Operation Reinhard. The mobile extermination squads were already conducting mass shootings of Jews in the Eastern territories since 1941 which were occupied earlier by the Soviets.[18] The Jews of Western Europe were either deported to ghettos emptied through massacres such as in the Latvian Riga, or sent directly to Treblinka, Belzec and Sobibór extermination camps built in spring and summer of 1942 only for gassing. Auschwitz II Birkenau chambers began operating in March. The last death camp, Majdanek, launched them in late 1942.[19]

At Wannsee, the SS estimated that the "Final Solution" could ultimately eradicate up to 11 million European Jews; Nazi planners envisioned the inclusion of Jews living in neutral and non-occupied countries such as Ireland, Sweden, Turkey, and the United Kingdom. Deportations on this scale required the coordination of numerous German government ministries and state organisations, including the Reich Main Security Office (RSHA), the Transport Ministry, and the Foreign Office. The RSHA coordinated and directed the deportations; the Transport Ministry organized train schedules; and the Foreign Office negotiated with German-allied states and their railways about "processing" their own Jews.[20]

In recent years, the German spokesman for the Train of Commemoration remembrance project, Hans-Rüdiger Minow told The Jerusalem Post that from among the World War II railway staff and officials, there is "no word about those who committed the crimes" even though 200,000 train employees were involved in the rail deportations and "10,000 to 20,000 were responsible for mass murders". The railwaymen were never prosecuted.[21]

The journey

The first trains with German Jews expelled to ghettos in occupied Poland began departing from central Germany on 16 October 1941.[23] Subsequently called Sonderzüge (special trains),[24] the trains had low priority for the movement and would proceed to the mainline only after all other transports went through, inevitably extending shipping time beyond expectations.[24]

The trains consisted of sets of either third class passenger carriages,[25] but mainly freight cars or cattle cars or both; the latter packed with up to 150 deportees, although 50 was the number proposed by the SS regulations. No food or water was supplied. The Güterwagen boxcars were only fitted with a bucket latrine. A small barred window provided irregular ventilation, which oftentimes resulted in multiple deaths from either suffocation or the exposure to the elements.[26] Some freight cars had a layer of quick lime on the floor.[27]

At times the Germans did not have enough filled up cars ready to start a major shipment of Jews to the camps,[4] so the victims were kept locked inside overnight at layover yards. The Holocaust trains waited for more important military trains to pass.[26] An average transport took about four days. The longest transport of the war, from Corfu, took 18 days. When the train arrived at the camp and the doors were opened, everyone was already dead.[4]

Due to delays and cramped conditions, many deportees died in transit. On 18 August 1942, Waffen SS officer Kurt Gerstein had witnessed at Belzec the arrival of "45 wagons with 6,700 people of whom 1,450 were already dead on arrival." That train came with the Jews of the Lwów Ghetto,[27] less than a hundred kilometers away.[28]

Point of arrival

The SS built three extermination camps in occupied Poland specifically for Operation Reinhard: Bełżec, Sobibór, and Treblinka. They were fitted with identical mass killing facilities disguised as communal shower rooms.[29] In addition, gas chambers were developed in 1942 at the Majdanek concentration camp,[29] and at Auschwitz II-Birkenau.[29][30] In German-occupied USSR at the Maly Trostinets extermination camp shootings were used to kill victims in the woods.[31] At the Chełmno extermination camp victims were killed in gas vans whose redirected exhaust fed into sealed compartments at the rear of the vehicle. They were utilized in Trostinets as well.[32] Neither of these two camps had international rail connections therefore the trains used to stop at the nearby ghettos in Łódź and in Minsk respectively.[33] From there, the prisoners were taken by trucks to die.[33][34] At Treblinka, Belzec, and Sobibor the killing mechanism consisted of a large internal-combustion engine delivering exhaust fumes to gas chambers through pipes.[35] At Auschwitz and Majdanek, the gas chambers relied on Zyklon B pellets of hydrogen cyanide, poured through vents in the roof from cans sealed hermetically.[35][36]

Once alighted, the prisoners were split by category. The old, the young, the sick and the infirm were sometimes separated for immediate death by shooting, while the rest were prepared for the gas chambers. In a single 14-hour workday, 12,000 to 15,000[37] people would be killed at any one of these camps.[35][38] The capacity of the crematoria at Birkenau was 20,000 bodies per day.[36][39] The selected new arrivals who looked healthy were put to slave labor in the Sonderkommandos, burying victims in mass graves and burning corpses under pain of death.[23]

The calculations

The standard means of delivery was a 10 metre long cattle freight wagon, although third class passenger carriages were also used when the SS wanted to keep up the "resettlement to work in the East" myth, particularly in the Netherlands and in Belgium. The SS manual covered such trains, suggesting a carrying capacity per each trainset of 2,500 people in 50 cars, each boxcar loaded with 50 prisoners. In reality however, boxcars were crammed with up to 100 persons and routinely loaded from the minimum of 150% to 200% capacity.[40] This resulted in an average of 5,000 people per trainset; 100 persons in each freight car multiplied by 50 cars. Notably, during the mass deportation of Jews from the Warsaw Ghetto to Treblinka in 1942 trains carried up to 7,000 victims each.[41]

In total, over 1,600 trains were organised by the German Transport Ministry, and logged mainly by the Polish state railway company taken over by Germany, due to the majority of death camps being located in occupied Poland.[42] Between 1941 and December 1944, the official date of closing of the Auschwitz-Birkenau complex, the transport/arrival timetable was of 1.5 trains per day: 50 freight cars × 50 prisoners per freight car × 1,066 days = 4,000,000 prisoners in total.[1]

On 20 January 1943, Himmler sent a letter to Albert Ganzenmüller, the Under-secretary of State at the Reich Transport Ministry, pledging: "need your help and support. If I am to wind things up quickly, I must have more trains."[43] Of the estimated 6 million Jews exterminated during World War II, 2 million were murdered on the spot by the military, political police, and mobile death squads of the Einsatzgruppen aided by the Orpo battalions and their auxiliaries. The remainder were shipped to their deaths elsewhere.

Payment

Most of the Jews were forced to pay for their own deportations, particularly wherever passenger carriages were used. This payment came in the form of direct money deposit to the SS in light of the "resettlement to work in the East" myth. Charged in the ghettos for accommodation the adult Jews paid full price one-way tickets, while children under 10–12 years of age paid half price. Those who were running out of money in the ghetto were loaded onto trains to the East as first, while those with some remaining supplies of gold and cash were shipped as last.[2]

The SS forwarded part of this money to the German Transport Authority to pay the German Railways for transport of the Jews. The Reichsbahn was paid the equivalent of a third class railway ticket for every prisoner transported to their destination: 8,000,000 passengers 4 Pfennig per track kilometer, times 600 km (average voyage length), equaled 240 million Reichsmarks. Children under four went free.[24]

The Reichsbahn pocketed both this money and their own share of the cash paid by the transported Jews after the SS fees. According to an expert report established on behalf of the German "Train of Commemoration" project, the receipts taken in by the state-owned Deutsche Reichsbahn for mass deportations in the period between 1938 and 1945 reached a sum of US $664,525,820.34.[44]

Operations across Europe

Powered mainly by efficient steam locomotives, the Holocaust trains were kept to a maximum of 55 freight cars on average, loaded from 150% to 200% capacity.[1] The participation of German State Railway (the Deutsche Reichsbahn) was crucial to the effective implementation of the "Final Solution of the Jewish Question". The DRB was paid to transport Jews and other victims of the Holocaust from thousands of towns and cities throughout Europe to meet their death in the Nazi concentration camp system.[1]

As well as transporting German Jews, DRB was responsible for coordinating transports on the rail networks of occupied territories and Germany's allies. The characteristics of organized concentration and transportation of victims of the Holocaust varied by country.

Belgium

After Germany invaded Belgium on 10 May 1940, all Jews were forced to register with the police as of 28 October 1940. The lists enabled Belgium to become the first country in occupied Western Europe to deport recently immigrating Jews.[47] The implementation of the "Final Solution" in Belgium centred on the Mechelen transit camp (Malines) chosen because it was the hub of the Belgian National Railway system.[47] The first convoy left Mechelen transit camp for extermination camps on 22 July 1942, although nearly 2,250 Jews had already been deported as forced laborers for [Organisation Todt] Error: {{Lang}}: text has italic markup (help) to Northern France.[48] By October 1942 some 16,600 people have been deported in 17 convoys. At this time deportations were temporarily halted until January 1943.[49][50] Those deported in the first wave were not Belgian citizens, resulting from the intervention by the Belgian Queen Elisabeth with the German authorities.[49] In 1943, the deportations of Belgians resumed.

In September, Jews with Belgian citizenship were deported for the first time.[49] After the war, the collaborator Felix Lauterborn stated in his trial that 80 per cent of arrests in Antwerp used information from paid informants.[51] In total, 6,000 Jews were deported in 1943, with another 2,700 in 1944. Transports were halted by the deteriorating situation in occupied Belgium before the liberation.[52]

The percentages of Jews which were deported varied by location. It was highest in Antwerp, with 67 per cent deported, but lower in Brussels (37 per cent), Liége (35 per cent) and Charleroi (42 per cent).[53] The main destination for the convoys was Auschwitz concentration camp in occupied Poland. Smaller numbers were sent to Buchenwald and Ravensbrück concentration camps, as well as Vittel concentration camp in France.[52] In total, 25,437 Jews were deported from Belgium.[52] Only 1,207 of these survived the war.[54]

The only time during World War II that a transport carrying Jewish deportees has been stopped happened on 19 April 1943, when the Transport No. 20 left Mechelen with 1,631 Jews, heading for Auschwitz. Soon after leaving Mechelen, the driver stopped the train after seeing an emergency red light, set by the Belgians. After a brief fire fight between the Nazi train guards and the three resistance members – equipped only with one pistol between them – the train started again. Of the 233 people who attempted to escape, 26 were shot on the spot, 89 were recaptured and 118 got away.[55][56]

Bulgaria

Bulgaria joined the Axis powers in March 1941 and took part in the invasion of Yugoslavia and Greece.[57] The Bulgarian government set up transit camps in Skopje, Blagoevgrad and Dupnitsa for the Jews from the former Serbian province of Vardar Banovina and Thrace (today's Republic of Macedonia and Greece).[57] The "deportations to the east" of 13,000 inmates,[58] mostly to Treblinka extermination camp began on 22 February 1943, predominantly in passenger cars.[59] In four days, some 20 trainsets departed under severely overcrowded conditions to occupied Poland requiring each train to stop daily to dump the bodies of Jews who died during the previous 24 hours.[43] In May 1943 the Bulgarian government led by King Boris expelled 20,000 Jews from Sofia and at the same time, made plans to deport Bulgaria's Jews to the camps pursuant to an agreement with Germany.[59]

A Holocaust train from Thrace was witnessed by Archbishop Stefan of Sofia who was shocked by what he saw. His protest letter along with those of other Orthodox clergymen were ignored by the King.[60] A demonstration in Sofia on 24 May 1943 by the Jewish community led by Rabbi Daniel Zion was quashed by Bulgarian police arresting 400 Jews.[60] Luckily, a small delegation under parliamentarian Dimitar Peshev managed to launch a successful protest at the Ministry of Internal Affairs.[59] The new order issued by Minister Petar Gabrovski to release the Jews already rounded up, was not reversed.[60] His decision prevented the Jewish community of 49,000 people from being exterminated in death camps of General Government.[60] Nevertheless, the Bulgarian Jews remained the subject of severe racial restrictions locally and were stripped by the government of currency, jewelry and gold handed over to the Bulgarian national bank.[61] According to Bulgarian historian Nissan Oren, King Boris did not show any humanitarian inclinations for the Jews of his country, and the later claims of his benevolence are without firm foundation.[62]

Bohemia and Moravia

Czechoslovakia was annexed by Nazi Germany in 1939. Within the new ethnic-Czech Protectorate of Bohemia and Moravia the Czechoslovak State Railways (ČSD) were taken over by the Reichsbann and the new German railway company Böhmisch-Mährische Bahn (BMB) was set up in its place.[63] The Czech human losses were considerably lower in World War II than among other nations (with a positive growth ratio), except for the Jews. One entire town was turned into a walled-off ghetto in 1941, and named Theresienstadt. In all, it contained around 50,000 Jews from the Protectorate and 37,000 from the Reich, with the remaining 20,000 Jews transported to other camps. Three-quarters of Bohemian and Moravian Jews died in the Holocaust,[64] of whom 33,000 died in Terezín.[65] The remainder were transported in Holocaust trains from Theresienstadt mainly to Auschwitz-Birkenau. The last train for Birkenau left Theresienstadt on 28 October 1944 with 2,038 Jews of whom 1,589 were immediately gassed.[66]

France

The French national SNCF railway company under the Vichy Government played its part in the "Final Solution". In total, the Vichy government deported more than 76,000 Jews,[67] without food or water (pleaded for by the Red Cross in vain),[67] as well as thousands of other so-called undesirables to German-built concentration and extermination camps aboard the Holocaust trains, pursuant to an agreement with the German government; fewer than 3 percent survived the deportations.[68][69] According to Serge Klarsfeld, president of the organization Sons and Daughters of Jewish Deportees from France, SNCF was forced by German and Vichy authorities to cooperate in providing transport for French Jews to the border and did not make any profit from this transport.[70] However, in December 2014, SNCF agreed to pay up to $60 million worth of compensation to Holocaust survivors in the United States.[71] It corresponds to approximately $100,000 per survivor.[72]

Drancy internment camp served as the main transport hub for the Paris area and regions west and south thereof until August 1944, under the command of Alois Brunner from Austria.[73] By 3 February 1944, 67 trains had left from there for Birkenau.[66] Vittel internment camp served the northeast, closer to the German border from where all transports were taken over by German agents. By 23 June 1943, 50,000 Jews had been deported from France, a pace that the Germans deemed too slow.[74] The last train from France left Drancy on 31 July 1944 with over 300 children.[66]

Greece

After the invasion and until September 1943 Grece was divided between the Italian, the Bulgarian, and the German zones of occupation. Most Greek Jews lived in Thessaloniki (Salonika) ruled by Germany, where the collection camp was set up for the Jews also from Athens and the Greek Islands. From there 45,000–50,000 Jews were sent to Auschwitz-Birkenau between March and August 1943, packed 80 to a wagon. There were also 13,000 Greek Jews in the Italian, and 4,000 Jews in the Bulgarian zone of occupation. In September 1943 the Italian zone was taken over by the Third Reich. Overall, some 60,000–65,000 Greek Jews were deported in Holocaust trains by the SS to Auschwitz, Majdanek, Dachau and the subcamps of Mauthausen before the war's end,[76][77] including over 90% of Thessaloniki's prewar population of 50,000 Jews. Of these, 5,000 Jews were deported to Treblinka from the regions of Thrace and from Macedonia in the Bulgarian share of the partitioned Greece, where they were gassed upon arrival.[77][78]

Hungary

While in alliance with Nazi Germany, Hungary acquired new provinces at both the First and the Second Vienna Awards (1938; 1940). The advancing Hungarian Army received vital help from the Hungarian State Railways (MÁV) in Northern Transylvania (Erdély).[79] By 1941 the number of Jews under Hungarian control grew to a total of 725,007 officially. Some 184,453 of them lived in Budapest.[80] Soon the non-native Jews were expelled from Hungarian territory. Some 20,000 Jews were transported to occupied Czechoslovakia and Yugoslavia, and the Transylvanian Jews were sent back to Romania.[81] Hungary took part in Operation Barbarossa supplying 50,000 Jewish slave workers for the Eastern Front. Most of them were dead by January 1943. Later that year Hitler discovered that Kállay secretly conferred with the Western Allies. To stop him, Germany launched the Operation Margarethe in March 1944, and took over control of all Jewish affairs.[80] On 29 April 1944 the first deportation of Hungarian Jews to Birkenau took place.[66] Between 15–25 May according to SS-Brigadeführer Edmund Veesenmayer 138,870 Jews had been deported. On 31 May 1944 Veesenmayer reported additional 60,000 Jews sent to the camps in six days, while the total for the past 16 days stood at 204,312 victims.[66] Between May and July 1944, helped by Hungarian police, the German Sicherheitspolizei deported nearly 440,000 Hungarian Jews mostly to Auschwitz-Birkenau,[82][83] or 437,000 at the rate of 6,250 per day.[66]

On 8 July 1944, due to international pressure by the Pope, the King of Sweden, and the Red Cross (all of whom had recently learned about the extent of it), the deportation of the Hungarian Jews had stopped.[66] In October 1944, following a coup d'état which put the Hungarian government back in control, 50,000 of the remaining Jews were forced on a death march to Germany, digging anti-tank ditches on the road westward. A further 25,000 were saved in an "international ghetto" under Swedish protection engineered by Carl Lutz and Raoul Wallenberg. When the Soviet Army liberated Budapest on 17 January 1945, of the original 825,000 Jews in the country,[84] less than 260,000 Jews were still alive,[84][85] including 80,000 Hungarian natives.[86][87]

On 30 June 1944 one Hungarian passenger train later known as the Kastner train transported 1,684 Jews to safety in Switzerland in exchange for gold, diamonds and cash.[88] It was organized by the Hungarian journalist and lawyer Rudolph Kastner, the de facto leader of the Zionist Aid and Rescue Committee (Vaada). For reasons that are still disputed, the Nazi officials under SS-Obersturmbannführer Adolf Eichmann sold them exit visas in exchange for 6.5 million pengő (RM 4,000,000 or $1,600,000).[89][90] In their secret negotiations with the SS, Vaada compiled a list of Jews to be considered including prominent individuals, "paying persons" (i.e. Orthodox Jews, and Zionists), orphans, known refugees,[89] as well as some 600 Jews who held Palestinian immigration certificates.[89] The list also controversially included 388 people from Kastner's home town of Cluj.[88][note 1]

In April 1944 the fascist government of Ferenc Szálasi issued a decree ordering all Jews under the Hungarian jurisdiction to "deposit" with the authorities their gems, gold jewellery ornamented with gems, items made with the use of precious metals, and all valuables including Oriental carpets, silver, furs, paintings and fine furniture.[93] These valuables were laden on a train consisting of 44 cars sent away ahead of the Soviet advance. This train was seized in May 1945 by U.S. occupation troops in Austria. The Hungarian escort pushed the train into a tunnel near Boeckstein where it was found by the Americans who took control of the railway station in Werfen. Two Hungarian lorries were seized in the French sector. The goods were stored in Salzburg, with the valuables in one location and paintings in another. After household items were given to furnish American families, the remainder was repatriated to America where in June 1948 it was sold at Parke-Bernet Galleries in New York.[94][note 2]

Italy

The popular view that Benito Mussolini resisted the deportation of Italian Jews to Germany is widely seen as simplistic by Jewish scholars,[96] because the Italian Jewish community of 47,000 constituted the most assimilated Jews in Europe.[97] About one out of every three Jewish males were members of the Fascist Party before the war began; more than 10,000 Jews who used to conceal their identity,[97] because antisemitism was part of the very ideal of italianità wrote Wiley Feinstein.[98]

The Holocaust came to Italy in September 1943 after the German takeover of the country due to its total capitulation at Cassibile.[98] By February 1944 the Germans shipped 8,000 Jews to Auschwitz-Birkenau via Austria and Switzerland,[99] although more than half of the victims arrested and deported from northern Italy were rounded up by the Italian police and not by the Nazis.[96] Also between September 1943 and April 1944, at least 23,000 Italian soldiers were deported to work as slaves in German war industry, while over 10,000 partisans were captured and deported during the same period to Birkenau. By 1944 there were over half a million Italians working inside the Nazi war machine.[100]

Netherlands

The Netherlands was invaded on 10 May 1940 and fell under the German military control. The community of native-Dutch Jews including the new Jewish refugees from Germany and Austria was estimated at 140,000.[101] Most natives were concentrated in the Amsterdam ghetto before being moved to Westerbork transit camp in the north-east near the German border. Deportees for "resettlement" leaving aboard the NS passenger and freight trains were unaware of their final destination or fate,[102] as postcards were often thrown from moving trains.[103]

Most of the approximately 100,000 Jews sent to Westerbork perished.[103] Between July 1942 and September 1944 almost every Tuesday a train left for Auschwitz-Birkenau and Sobibor extermination camps, or Bergen-Belsen and Theresienstadt, in a total of 94 outgoing trains. About 60,000 prisoners were sent to Auschwitz and 34,000 to Sobibor.[76][104] At liberation approximately 870 Jews remained in Westerbork. Only 5,200 deportees survived, most of them in Theresienstadt, approximately 1980 survivors, or Bergen-Belsen, approximately 2050 survivors. From those on the sixty-eight transports to Auschwitz 1052 people returned, including 181 of the 3450 people taken from eighteen of the trains at Cosel. There were 18 survivors out of approximately one thousand people selected from the nineteen trains to Sobibor, the remainder was murdered on arrival. For the Netherlands the overall survival rate among Jews who boarded the trains for all camps was 4.86 percent.[105][106] On 29 September 2005, the Dutch national rail company Nederlandse Spoorwegen (NS) apologised for its role in the deportation of Jews to the death camps.[107]

Poland

Following invasion of Poland in September 1939 Nazi Germany disbanded Polish National Railways (PKP) immediately and handed over their assets to the Deutsche Reichsbahn in Silesia, Greater Poland and in Pomerania.[108] The Polish management was either executed in mass shooting actions (see: the 1939 Intelligenzaktion and the 1940 German AB-Aktion in Poland) or imprisoned. The brand new Eastern division of DRB acquired 7,192 kilometres (4,469 mi) of new railway lines and 1,052 km of (mostly industrial) narrow gauge.[109] Managerial jobs were staffed with German officials in a wave of some 8,000 instant promotions.[108] The first Polish area subjected to forcible deportation of Polish nationals was the port city of Gdynia strategically important to Nazi Germany. Beginning in mid October 1939 (one and a half month after the attack), DRB began transporting Polish families to Częstochowa, Kraków, Kielce and Lublin. The Poles were required to leave the keys in the doors of their homes and businesses, for the incoming families of German industrial workers and administration of their enterprises. Poles were given only a few hours to pack carry-on luggage, about 30 kilograms (66 lb) per person. In total, some 70,000-80,000 civilians have been expelled from Gdynia alone.[110] The parallel expulsion of Poles from Silesia entailed the forcible displacement of some 18,000–20,000 people during Action Saybusch. The total number of Poles deported from the region grew to around 50,000 before 1944.[111]

In November 1939, as soon as the semi-colonial General Government was set up in occupied central Poland, a separate branch of DRB called Generaldirektion der Ostbahn (Kolej Wschodnia in Polish) was established with headquarters called GEDOB in Kraków.[108] All of the DRB branches existed outside Germany proper.[112] The Ostbahn was granted 3,818 kilometres (2,372 mi) of railway lines (nearly doubled by 1941) and 505 km of narrow gauge, initially.[109] In December 1939, on the request of Hans Frank in Berlin, the Ostbahndirektion was given financial independence after paying back 10 million Reichsmarks to DRB.[113] The removal of all bomb damage was completed in 1940.[114]

The German SS employed Ostbahn to conduct the first mass transport to Auschwitz concentration camp (which just opened) in mid June 1940.[116] Notably, the Birkenau infamous "Gate of Death" (pictured above) for the incoming freight trains at Auschwitz was built in 1943 long after its gas chambers went into operation.[117] Trains were used during the ethnic cleansing operations to create "living space in the East" for the German settlers. Deportations were part of a broader Nazi policy called the Generalplan Ost, whose final version was essentially a grand plan for genocide divided into phases: the "Small Plan" (Kleine Planung) covered the actions which were to be taken during the war, and the "Big Plan" (Grosse Planung) covered intended strategy to be realized after the war was won.[118][119] Hitler intended to destroy the Polish nation completely within 10 to 20 years, and resettle the prewar Poland with ethnically German colonists.[120] The plan resulted in a massive Nazi German operation consisting of the forced resettlement of over 1.7 million ethnic Poles from the annexed territories of occupied Poland.[121] Poles were deported to any one of the German forced labour camps including over 30 Polenlager camps either in Germany itself or in the occupied territories.[122]

Mass deportation of Polish nationals using freight trains (but also lorries and even horse-drawn wagons) took place from November 1942 to July 1943 during the ethnic cleansing of Zamojszczyzna by Nazi Germany, in which all branches of German police including Orpo and Sonderdienst including Wehrmacht and the Ukrainian Auxiliary Police,[123] forcibly removed over 110,000 Poles from 300 villages, including around 30,000 children most of whom were never found.[124] In the second phase of the latter plan, German occupants decided to settle Ukrainians in the area of Zamość region (Zamojszczyzna, "Zamość Lands"), brought in the Ukraineraktion to form a buffer zone to protect the 10,000 German colonists brought in the Heim ins Reich action from Romania and to antagonize Ukrainians with the remaining Poles. In the areas surrounding those from which Poles had been forcibly removed by Germans over 7,000 Ukrainians were settled in 63 previously Polish villages of the Hrubieszów county, while 15,000 Poles were removed, 5,5 out of which by forcible relocation, and the remainders escaped. By the end of March 1943, 116 villages of the Zamość region (Zamojszczyzna) had already been cleared of their Polish inhabitants.,[125][126]

The Deutsche Reichsbahn acquired new infrastructure in Poland worth in excess of 8,278,600,000 złoty,[128] including some of the largest locomotive factories in Europe, the H. Cegielski – Poznań renamed DWM, and Fablok in Chrzanów renamed Oberschlesische Lokomotivwerke Krenau producing engines Ty37 and Pt31 (designed in Poland), as well as the locomotive parts factory Babcock-Zieleniewski in Sosnowiec renamed Ferrum AG later tasked with making parts to V-1 i V-2 rockets also.[129] Under the new management, formerly Polish companies began producing German engines BR44, BR50 and BR86 as early as 1940 virtually for free, using forced labor. All Polish railwaymen were ordered to return to their place of work, or face death. Beating with fists became commonplace, although perceived as shocking by Polish long-term professionals. Their public executions were introduced in 1942.[109] By 1944, the factories in Poznań and Chrzanów were mass-producing the redesigned "Kriegslok" BR52 locomotives for the Eastern front, all stripped of coloured metals by the rule with intentionally shortened lifespan.[108]

Before the onset of Operation Reinhard which marked the most deadly phase of the Holocaust in Poland many Jews were transported by road to killing sites such as the Chełmno extermination camp, equipped with gas vans. In 1942, stationary gas chambers were built at Treblinka, Belzec, Sobibor, Majdanek and Auschwitz. After the Nazi takover of prewar Polish railway company PKP, the train movements, originating inside and outside occupied Poland and terminating at death camps, were tracked by Dehomag using IBM-supplied card-reading machines and traditional waybills produced by the Reichsbahn.[42] The Holocaust trains were always managed and directed by native German SS men posted with that express' role throughout the system.[130]

The shipments to camps under Operation Reinhard came mainly from the ghettos. The Warsaw Ghetto created by Nazi Germans on 16 November 1940 held eventually over 450,000 Jews cramped in an area meant for about 60,000 people. The second-largest Łódź Ghetto held 204,000 Jews. Both ghettos had collection points known as Umschlagplatz along the rail tracks, with most deportations from Warsaw to Treblinka taking place between 22 July through to 12 September 1942.[131][132][133] The gassing at Treblinka started on 23 July 1942, with two pendulum trains delivering victims six days each week ranging from about 4,000 to 7,000 victims per transport, the first in the early morning and the second in the mid-afternoon.[134] All new arrivals were sent immediately to the undressing area by the Sonderkommando squad that managed the arrival platform, and from there to the gas chambers. According to German records, including the official report by SS Brigadeführer Jürgen Stroop, some 265,000 Jews were transported in freight trains from the Warsaw Ghetto to Treblinka during this period. The murder operation code-named Grossaktion Warsaw concluded several months before the subsequent Warsaw Ghetto Uprising resulting in new deportations.[135] The Nazi 1942 record of the total number of victims most of whom were transported by train to Operation Reinhard death camps, including cumulative numbers known today, is as follows:

|

|

The Höfle Telegram lists the number of arrivals to the Reinhard camps through 1942 as 1,274,166 Jews based on Reichsbahn own records. The last train to be sent to Treblinka extermination camp left Białystok Ghetto on 18 August 1943; all prisoners were killed in gas chambers after which the camp closed down per Globocnik's directive.[74] Of the more than 245,000 Jews who passed through the Łódź Ghetto,[140] the last 68,000 inmates, by then the largest final gathering of Jews in all of German occupied Europe, have been liquidated by the Nazis after 7 August 1944. They were told to prepare for resettlement; instead, over the next 23 days they were sent to Birkenau by train at the rate of 2,500 per day, with some of the crippled selected by Josef Mengele for his "medical experiments".[66]

The rail traffic on most Polish railway lines was extremely dense. In 1941 an average of 420 German trains were passing through every 24 hours on top of Polish internal traffic; in 1944 the number rose to 506 military transports per day.[109] No new lines have been built by Nazi Germany. Most supplies from layover yards were taken away. However, almost all Polish language signs were replaced with German, which led to new problems. On 24 November 1944 two trains (one German with military cargo, and one Polish) traveling at regular speeds collided head-on in Barwałd Średni near Wadowice. It was the biggest train collision of World War II in occupied Poland with both locomotives and nearly half of their trainsets destroyed completely. Some 130 people from the Polish passenger train were killed and over 100 wounded.[141][142]

Romania

Căile Ferate Române (Romanian Railways) were involved in the transport of Jewish and Romani people to concentration camps in Romanian Old Kingdom, Bessarabia, northern Bukovina, and Transnistria.[143] In a notable example, after the Iasi pogrom events, Jews were forcibly loaded onto freight cars with planks hammered in place over the windows and traveled for days in unimaginable conditions. Many died and were gravely affected by lack of air, blistering heat, lack of water, food or medical attention. These veritable death trains arrived to their destinations Podu Iloaiei and Călăraşi with only one-fifth of their passengers alive.[143][144][145] No official apology was released yet by Căile Ferate Române for their role in the Holocaust in Romania.

Scandinavia

Norway surrendered to Nazi Germany on 10 June 1940. At the time, there were 1,700 Jews living in Norway. About half of them escaped to neutral Sweden. Round ups by the SS began in the fall of 1942 with support of the Norwegian police. In late November 1942 all Jews of Oslo including women and children were put on a ship requisitioned by the Quisling government and taken to Hamburg, Germany. From there, they were deported to Auschwitz-Birkenau by train. In total, 770 Norwegian Jews were sent by boat to Nazi Germany between 1940 and 1945. Only two dozen survived.[146]

Slovakia

On 9 September 1941, the parliament of the Slovak Republic – a Nazi puppet state – ratified the Jewish Codex, a series of laws and regulations that stripped Slovakia's 80,000 Jews of their civil rights and all means of economic survival. The fascist Slovak leadership was so impatient to get rid of Jews that it paid the Nazis DM 500 in exchange for each expelled Jew and a promise that the deportees would never return to Slovakia. The decision by Slovakia to initiate and pay for the expulsion was unprecedented among the satellite states of Nazi Germany. They paid 40 millions RM to the SS for it. Some 83 percent of the Jewish population perished in two waves of deportations to Auschwitz, Belzec, and Majdanek; the second wave after the Uprising of 28–29 August 1944.[147]

Switzerland

Switzerland was not invaded because its mountain bridges and tunnels between Germany and Italy were too vital for them to go into war.[148] Also, the Swiss banks provided necessary access to international markets by dealing in pilfered gold.[149] There were 18,000 Jews living in Switzerland at the onset of World War II.[150] The country did not turn over their own Jews to the Germans, but according to eye-witness,[151] allowed the Holocaust trains (aware of them since 1942) to use the Gotthard Tunnel on the way to the camps.[150] Most war supplies to Italy were shipped through the Austrian Brenner Pass.[152]

There exists substantial evidence that these shipments included Italian forced labour workers and trainloads of Jews in 1944 during the Nazi occupation of northern Italy,[151] when a German train passed through Switzerland every 10 minutes. The need for the tunnel was complicated by the British Royal Air Force having bombed and disrupted services through the Brenner Pass, as well as a heavy snowfall in the winter of 1944–45.[100]

Of 43 trains that could be tracked down by the 1996 Bergier Commission, 39 went via Austria (Brenner, Tarvisio), one via France (Ventimiglia-Nice). The commission could not find any evidence that the other three passed through Switzerland. It is possible that the train could have been carrying dissidents back from concentration camps. Started in 1944, some repatriation trains went through Switzerland officially, organised by the Red Cross.[148][153]

Aftermath

After the Soviet Army began making severe inroads into the German-occupied Europe and the Allies landed in Normandy in June 1944, the number of trains and transported persons began to vary greatly. By November 1944, with the closure of Birkenau and the advance of the Soviet Army, the death trains had ceased. Conversely, the subsequent death marches had the advantage of being able to utilize the forced labour to build defences.

As the Soviet and Allied Armies made their final pushes, the Nazis transported some of the concentration camp survivors either to other camps located inside the collapsing Third Reich, or to the border areas where they believed they could negotiate the release of captured Nazi Prisoners of War in return for the "Exchange Jews" or those that were born outside the Nazi occupied territories. Many of the inmates were transported via the infamous death marches, but among other transports three trains left Bergen-Belsen in April 1945 bound for Theresienstadt—all were liberated.[106]

The last recorded train is the one used to transport the women of the Flossenbürg March, where for three days in March 1945 the remaining survivors were crammed into cattle cars to await further transport. Only 200 of the original 1000 women survived the entire trip to Bergen-Belsen.[154]

Remembrance and commemoration

There are numerous national commemorations of the mass transportation of Jews in the "Final Solution" across Europe, as well as some lingering controversies surrounding the history of the railway systems utilized by the Nazis.

Poland

All railway lines leading to death camps built in occupied Poland are ceremonially cut off from the existing railway system in the country, similar to the well-preserved arrival point at Auschwitz known as the "Judenrampe" platform. The commemorative monuments are traditionally erected at collection points elsewhere. In 1988 a national monument was created at the Umschlagplatz of the Warsaw Ghetto. Designed by architect Hanna Szmalenberg and sculptor Władysław Klamerus, it consists of a stone structure symbolizing an open freight car.[155] In Kraków, the memorial to Jews from the Kraków Ghetto deported during the Holocaust spreads over the entire deportation site known as the Square of the Ghetto Heroes (Plac Bohaterow Getta). Inaugurated in December 2005, it consists of oversized steel chairs (each representing 1,000 victims), designed by architects Piotr Lewicki and Kazimierz Latak.[156] At the former Łódź Ghetto, the monument was built at the Radegast train station (Bahnhof Radegast), where approximately 200,000 Polish, Austrian, German, Luxemburg and Czech Jews boarded the trains on the way to their deaths in the period from 16 January 1942, to 29 August 1944.[157][158]

Germany

In 2004/2005, German historians and journalists began publicly demanding that at the German passenger train stations commemorative exhibits be set up, after the railroad companies in France and the Netherlands began commemorations of Nazi mass deportations in their own train stations.[159] The Deutsche Bahn AG (DB AG), the state-owned successor of the Deutsche Reichsbahn replied: "we do not have either the personnel or the financial resources" for that kind of commemoration.[160] Demonstrations then began at railway stations in Frankfurt am Main and in Cologne as well as inside the long-distance border-crossing trains.[161] Because the DB AG had responded by having its security personnel repress the protests, German citizens' initiatives rented a historical steam locomotive and installed their own exhibition in remodeled passenger cars. This "Train of Commemoration" made its first journey on the 2007 International Holocaust Remembrance Day of January 27. The Deutsche Bahn AG refused it access to the main stations in Hamburg and Berlin.[162][163] German Jewish communities protested against the company levying mileage tariffs and hourly fees for the exhibit (which by December 31, 2013 reached approx. US $290,000).[164]

Parliamentarians of all parties in the German national parliament called on the DB AG to rethink its behavior.[165] Federal Transport Minister Wolfgang Tiefensee proposed an exhibition by artist Jan Philipp Reemtsma on the railways' role in the deportation of 11,000 Jewish children to their deaths in Nazi concentration and extermination camps throughout World War II. Because the CEO of the railroad company maintained his refusal, a "serious rift" occurred between himself and the Minister of Transport.[166] On January 23, 2008, a compromise was reached, wherein the DB AG established its own stationary exhibit Sonderzüge in den Tod [Chartered Trains to Death – Deportation with the German Reichsbahn].[167] As national press journals pointed out, the exhibit "contained nearly nothing about the culprits." The post-war careers of those in charge of the railroad remained "totally obscured."[168] Since 2009 the civil society association Train of Commemoration which, with its donations financed the exhibition "Train of Commemoration" presented at 130 German stations with 445,000 visitors, has been demanding cumulative compensation for the survivors of these deportations by train. The railroad's proprietors (the German Minister of Transport and the German Minister of Finances) reject this demand.[169]

France

In 1992, SNCF commissioned a report on its involvement in World War II. The company opened its archives to an independent historian, Christian Bachelier, whose report was released in French in 2000.[170][171][172] It was translated to English in 2010.[173]

In 2001, a lawsuit was filed against French government-owned rail company SNCF by Georges Lipietz, a Holocaust survivor, who was transported by SNCF to the Drancy internment camp in 1944.[174] Lipietz was held at the internment camp for several months before the camp was liberated.[175] After Lipietz's death the lawsuit was pursued by his family and in 2006 an administrative court in Toulouse ruled in favor of the Lipietz family. SNCF was ordered to pay 61,000 Euros in restitution. SNCF appealed the ruling at an administrative appeals court in Bordeaux, where in March 2007 the original ruling was overturned.[174][176] According to historian Michael Marrus, the court in Bordeaux "declared the railway company had acted under the authority of the Vichy government and the German occupation" and as such could not be held independently liable.[170] [note 3] Marrus wrote in his 2011 essay that the company has nevertheless taken responsibility for their actions and it is the company's willingness to open up their archives revealing involvement in the transportation of Holocaust victims that has led to the recent legal and legislative attention.[170]

Between 2002 and 2004 the SNCF helped fund an exhibit on deportation of Jewish children that was organized by Nazi hunter Serge Klarsfeld.[170] In 2011, SNCF helped set up a railway station outside of Paris to a Shoah Foundation for the creation of a memorial to honor Holocaust victims.[171] In December 2014, the company came to a $60 million compensation settlement with French Holocaust survivors living in the United States.[71]

Netherlands

Nederlandse Spoorwegen used its 29 September 2005 apology for its role in the "Final Solution" to launch an equal opportunities and anti-Discrimination policy, in part to be monitored by the Dutch council of Jews.[183]

Railway companies involved

- Deutsche Reichsbahn, the German Reich Railway

- NMBS/SNCB, National Railway Company of Belgium

- Nederlandse Spoorwegen (NS) in the Netherlands [183]

- SNCF, French National Railway Company [184]

- CFR, the state railways of Romania

- MÁV, Hungarian State Railways

Footnotes

- ^ Although Kastner was later criticised for putting his own family on the train, Hansi Brand, a member of the Vaada testified at Eichmann's trial in Jerusalem in 1961 that Kastner had included his family to reassure the others that the train was safe, and was not destined, as they feared, for Auschwitz.[91][92]

- ^ To date, of the 1,176 paintings on the Gold Train originally stored by the U.S. Army, only one has been repatriated.[94] On 30 September 2005, the U.S. Government reached agreement with the representatives of the Hungarian Jewish community to pay $25.5 million in compensation with additional $500,000 for the creation of archives preserving documents associated with the Gold Train, and to declassify any remaining documents related to it.[95]

- ^ Following the Lipietz trial, SNCF's involvement in World War II became the subject of attention in the United States when SNCF explored bids on rail projects in Florida and California, and SNCF's partly owned subsidiary, Keolis Rail Services America bid on projects in Virginia and Maryland.[173] In 2010, Keolis placed a bid on a contract to operate the Brunswick and Camden lines of the MARC train in Maryland.[173] Following pressure from Holocaust survivors in Maryland, the state passed legislation in 2011 requiring companies bidding on the project to disclose their involvement in the Holocaust.[177][178] Keolis currently operates the Virginia Railway Express, a contract the company received in 2010.[173][177] In California, also in 2010, state lawmakers passed the Holocaust Survivor Responsibility Act. The bill, written to require companies to disclose their involvement in World War II,[179] was later vetoed by Governor Arnold Schwarzenegger.[178][180] While bidding on these rail contracts, SNCF was criticized for not formally acknowledging and apologizing for its involvement in World War II. In 2011, SNCF chairman Guillaume Pepy released a formal statement of regrets for the company's actions during World War II.[171][181][182] Some historians have expressed the opinion that SNCF has been unfairly targeted in the United States for their involvement in World War II. Human rights attorney Arno Klarsfeld has argued that the negative focus on SNCF was disrespectful to the French railway workers who lost their lives engaging in acts of resistance.[171]

Citations

- ^ a b c d e Hedi Enghelberg (2013). The trains of the Holocaust. Kindle Edition. p. 63. ISBN 978-160585-123-5.

Book excerpts from Enghelberg.com.

{{cite book}}: External link in|quote= - ^ a b Prof. Ronald J. Berger, University of Wisconsin–Whitewater (2002). Fathoming the Holocaust: A Social Problems Approach. Transaction Publishers. pp. 57–58. ISBN 0202366111.

Bureaucrats in the Reichsbahn performed important functions that facilitated the movement of trains. They constructed and published timetables, collected fares, and allocated cars and locomotives. In sending Jews to their death, they did not deviate much from the routine procedures they used to process ordinary train traffic.

- ^ Simone Gigliotti, Victoria University, Australia (2009). The Train Journey: Transit, Captivity, and Witnessing in the Holocaust. Berghahn Books. pp. 36, 55. ISBN 184545927X.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ a b c Ben Hecht, Julian Messner (December 31, 1969), Holocaust: The Trains. Aish.com Holocaust Studies.

- ^ HOLOCAUST FAQ: Operation Reinhard: A Layman's Guide (2/2).

- ^ Tomasz Wiścicki (16 April 2013), Train station to hell. Treblinka death camp retold by Franciszek Ząbecki [Stacja tuż obok piekła. Treblinka w relacji Franciszka Ząbeckiego], Muzeum Historii Polski [Museum of Polish History], retrieved 2 February 2016 – via Internet Archive,

Wspomnienia dawne i nowe by Franciszek Ząbecki (en), Pax publishig, Warsaw 1977.

; also in Clancy Young (2013), Treblinka Death Camp Day-by-Day. Tables with record of daily deportations, Holocaust Education & Archive Research Team, retrieved 2 February 2016 – via Internet Archive,Timeline of Treblinka (en).

- ^ Yad Vashem (2014), Nazi Germany and the Jews 1933-1939, archived from the original on 7 Feb 2014

- ^ Louis Bülow (2014), Sir Nicholas Winton, archived from the original on 7 Feb 2014

- ^ Types of Ghettos. United States Holocaust Memorial Museum, Washington, D.C.

- ^ a b Raul Hilberg. "German Railroads / Jewish Souls". The Role of the German Railroads in the Destruction of the Jews. Society, vol. 14, no. 1 (December 1976), pp. 162-174. Retrieved 5 February 2014.

- ^ "1939: The War Against The Jews." The Holocaust Chronicle published by Publications International, April 2000.

- ^ Michael Berenbaum, The World Must Know, United States Holocaust Memorial Museum, 2006, p. 114.

- ^ a b Peter Vogelsang & Brian B. M. Larsen, "The Ghettos of Poland." The Danish Center for Holocaust and Genocide Studies. 2002.

- ^ Marek Edelman. "The Ghetto Fights". The Warsaw Ghetto: The 45th Anniversary of the Uprising. Literature of the Holocaust, at the University of Pennsylvania.

- ^ François Furet, Unanswered Questions: Nazi Germany and the Genocide of the Jews. Schocken Books (1989), p. 182; ISBN 0-8052-4051-9.

- ^ "Deportation and transportation". The Holocaust Explained. London Jewish Cultural Centre. 2011. Retrieved 6 February 2014.

- ^ The Holocaust Chronicle. "Reichsbahn". Death and Resistance. Publications International. p. 415. Retrieved 6 February 2014.

- ^ Rossino, Alexander B. (2003). "Polish 'Neighbors' and German Invaders: Contextualizing Anti-Jewish Violence in the Białystok District during the Opening Weeks of Operation Barbarossa". Polin. 16. Note 97.

Cited in German court hearing: Vernehmung von Oberregierungsrat Graf von dem G., 2 September 1960. ZStL, 5 AR-Z 13/62, p. 11.

- ^ Jewish Virtual Library (2009). "Gas Chambers at Majdanek". Majdanek, Auschwitz II, Sobibor, Belzec and Treblinka. The American-Israeli Cooperative. Retrieved 11 February 2014.

- ^ German Railways and the Holocaust at the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum.

- ^ Benjamin Weinthal, Berlin (2008-04-17). "Mobile Holocaust exhibit forced to skip stop to ensure German railway system run on time". No Berlin stop for Shoah train. The Jerusalem Post. Retrieved 5 February 2014.

- ^ "The Auschwitz Album". Yad Vashem. Retrieved 4 February 2014.

- ^ a b "The Holocaust". Concentration Camps & Death Camps. Raiha Evelyn. Retrieved 4 February 2014.

- ^ a b c Richard L. Rubenstein, John K. Roth (2003). Approaches to Auschwitz (Google Books search inside). Westminster John Knox Press. p. 362.

- ^ Michael Nadel, Recalling the Holocaust

- ^ a b Joshua Brandt (April 22, 2005). "Holocaust survivor gives teens the straight story". Jewish news weekly of Northern California. Retrieved 5 February 2014.

- ^ a b Kurt Gerstein, "Gerstein Report" in English translation. Tübingen, 4 May 1945.

- ^ Holocaust Encyclopedia, "Belzec: Chronology" United States Holocaust Memorial Museum, 2013.

- ^ a b c Yad Vashem (2013). "Aktion Reinhard" (PDF file, direct download 33.1 KB). Shoah Resource Center, The International School for Holocaust Studies. Retrieved 6 April 2014.

- ^ Grossman, Vasily (1946). "The Treblinka Hell" (PDF). Moscow: Foreign Languages Publishing House. (online). Retrieved 6 April 2014 – via direct download 2.14 MB.

- ^ Yad Vashem (2013). "Maly Trostinets" (PDF file, direct download, 19.5 KB). Shoah Resource Center, The International School for Holocaust Studies. Retrieved 1 September 2013.

- ^ "The genocide: 1942 (Chelmno, Maly Trostinets)". Peace Pledge Union. Retrieved 6 April 2014.

- ^ a b "Maly Trostinec". ARC 2005. Retrieved 6 April 2014.

Maly Trostinec most closely resembled Chelmno, although at Maly Trostinec murder was principally committed by shooting.

- ^ Chris Webb & Carmelo Liscioto. "Maly Trostinets. The Death Camp near Minsk". Holocaust Research Project.org 2008. Retrieved 6 April 2014.

Jews were killed by means of mobile gas chambers... and shot to death in front of pits, 50 meters long and 3 metres deep.

- ^ a b c Arad, Yitzhak (1987). Belzec, Sobibor, Treblinka. The Operation Reinhard Death Camps (Google Books preview). Bloomington, Indianapolis: Indiana University Press. p. 31. ISBN 0-253-21305-3.

Testimony of SS Scharführer Erich Fuchs in the Sobibor-Bolender trial, Düsseldorf.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - ^ a b Piper, Franciszek (1994). "Gas Chambers and Crematoria". In Gutman, Yisrael; Berenbaum, Michael (eds.). Anatomy of the Auschwitz Death Camp. Bloomington, Indiana: Indiana University Press. pp. 169–170. ISBN 0-253-32684-2.

- ^ Alex Woolf (2008). A Short History of the World.

- ^ McVay, Kenneth (1984). "The Construction of the Treblinka Extermination Camp". Yad Vashem Studies, XVI. Jewish Virtual Library.org. Retrieved 3 November 2013.

- ^ Friedlander, Saul (2009). The Years of Extermination. New York: HarperCollins. ISBN 978-0-06-198000-8.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - ^ Geoffrey P. Megargee (2009). The United States Holocaust Memorial Museum Encyclopedia of Camps and Ghettos, 1933-1945. Indiana University Press. p. 1514. ISBN 0253003504. Retrieved 4 February 2014.

- ^ "Treblinka: Railway Transports". This Month in Holocaust History. Yad Vashem. Retrieved 4 February 2014.

- ^ a b Edwin Black on IBM and the Holocaust

- ^ a b NAAF Project. "The Holocaust timeline: 1943". NeverAgain.org, Internet Archive. Retrieved 5 February 2014.

- ^ Train of Commemoration (November 2009). Expert Report on the Deutsche Reichsbahn‘s Receipts (PDF file, direct download 740 KB from Wayback Machine) (in German, English, French, and Polish). Train of Commemoration Registered, Non-Profit Association, Berlin. Retrieved 4 February 2014.

With payment summaries, tables and literature.

{{cite book}}:|work=ignored (help); Italic or bold markup not allowed in:|publisher=(help) - ^ Claude Lanzmann Shoah Collection (July 1978). Henryk Gawkowski and Treblinka railway workers (Clips viewable online) (Camera Rolls #4-7) (in Polish and French). USHMM, Washington, DC: Steven Spielberg Film and Video Archive. Event occurs at 02:10:59 and 07:10:16. ID: 3362-3372. Retrieved 8 September 2015.

- ^ Schreiber, Marion (2003). The Twentieth Train: the True Story of the Ambush of the Death Train to Auschwitz (1st US ed.). New York: Grove Press. p. 203. ISBN 978-0-8021-1766-3.

- ^ a b "The Destruction of the Jews of Belgium". Holocaust Education & Archive Research Team. Retrieved 28 February 2014.

Native-born Belgian Jews were first noticed at Auschwitz after 744 of them were received at the camp following deportation of 998 Jews from Mechelen on 5 August 1942.

- ^ Yahil, Leni (1991). The Holocaust: The Fate of European Jewry, 1932–1945. Studies in Jewish History (Reprint (trans.) ed.). Oxford: Oxford University Press. p. 393. ISBN 0-19-504523-8.

- ^ a b c Yahil, Leni (1991). The Holocaust: The Fate of European Jewry, 1932–1945. Studies in Jewish History (Reprint (trans.) ed.). Oxford: Oxford University Press. p. 435. ISBN 0-19-504523-8.

- ^ Yahil, Leni (1991). The Holocaust: The Fate of European Jewry, 1932–1945. Studies in Jewish History (Reprint (trans.) ed.). Oxford: Oxford University Press. p. 394. ISBN 0-19-504523-8.

- ^ Saerens, Lieven (2008). De Jodenjagers van de Vlaamse SS. Lannoo. p. 188. ISBN 90-209-7384-3.

- ^ a b c Yahil, Leni (1991). The Holocaust: The Fate of European Jewry, 1932–1945. Studies in Jewish History (Reprint (trans.) ed.). Oxford: Oxford University Press. p. 436. ISBN 0-19-504523-8.

- ^ Saerens, Lieven (1998). "Antwerp's Attitudes towards the Jews from 1918–1940 and its Implications for the Period of Occupation". In Michman, Dan (ed.). Belgium and the Holocaust: Jews, Belgians, Germans (2nd ed.). Jerusalem: Yad Vashem. p. 194. ISBN 965-308-068-7.

- ^ Waterfield, Bruno (17 May 2011). "Nazi hunters call on Belgium's justice minister to be sacked". The Telegraph. Retrieved 26 February 2013.

- ^ a b "Escaping the train to Auschwitz". BBC News. 20 April 2013. Retrieved 20 April 2013.

Policeman John Aerts who helped the runaways evade recapture and return to Brussels was later declared a "Righteous Gentile" by Yad Vashem in Jerusalem. Of the three resistance workers: Robert Maistriau was arrested in March 1944, liberated from Bergen-Belsen in 1945, and lived until 2008; Youra Livschitz was later captured and executed; Jean Franklemon was arrested and sent to Sachsenhausen, liberated from there in May 1945, and died in 1977.

{{cite news}}: Unknown parameter|authors=ignored (help) - ^ When the Twentieth convoy arrived at Auschwitz, 70% of the women and girls were gassed immediately on arrival. Sources claim that all of the remaining women from Belgian Transport No.20 were sent to Block X of Birkenau for medical experimentation.[55]

- ^ a b Persecution of Jews in Bulgaria United States Holocaust Memorial Museum, Washington, DC.

- ^ PRWEB (28 February 2011). "International Jewish Committee Calls on Bulgaria to Clarify Their Role in the Deportation of 13,000 Jews to Treblinka". Vocus PRWeb. Retrieved 23 June 2015.

- ^ a b c Holocaust Encyclopedia (10 June 2013). "Treblinka: Chronology". United States Holocaust Memorial Museum. Archived from the original (Internet Archive) on 5 June 2012. Retrieved 9 December 2013.

Deportations from Bulgarian-occupied territory among others.

- ^ a b c d Rossen V. Vassilev, The Rescue of Bulgaria's Jews in World War II New Politics, Winter 2010, Vol: XII-4.

- ^ Michael Bar-Zohar, Beyond Hitler’s grasp: the heroic rescue of Bulgaria’s Jews. Holbrook, Mass.: Adams Media, 1998. ISBN 1-58062-060-4. Review.

- ^ Jewish Virtual Library, World War II & the Holocaust Bulgaria Virtual Jewish History Tour.

- ^ OKm11 at Locomotives.com.pl.

- ^ Hugh LeCaine Agnew. The Czechs and the Lands of the Bohemian Crown. Hoover Press, 2004. p. 215. ISBN 0817944923.

- ^ "The Holocaust Chronicle", Roots of the Holocaust, Prologue: p. 282, Publications International, 2009, retrieved 16 February 2014

- ^ a b c d e f g h NAAF Holocaust Project Timeline: 1944. NAAF Holocaust Project.

- ^ a b Committee on the Judiciary (20 June 2012). "Holocaust-Era Claims in the 21st Century, Hearing" (PDF file, direct download 2.58 MB). One Hundred Twelfth Congress, Second Session. United States Senate. p. 4 (8 / 196). Retrieved 6 February 2014.

- ^ J.-L. Einaudi and Maurice Rajsfus, Les silences de la police—16 July 1942 and 17 October 1961, L'Esprit frappeur, 2001, ISBN 2-84405-173-1

- ^ Bremner, Charles (2008-11-01). "Vichy gets chance to lay ghost of Nazi past as France hosts summit". London: The Times. Retrieved 2008-11-01.

- ^ Serge Klarsfeld (26 June 2012). "Analysis of Statements Made During the June 20, 2012 Hearing of the U.S. Senate Committee of the Judiciary" (PDF). Memorial de la Shoah. Retrieved 19 November 2013.

- ^ a b France to compensate American Holocaust survivors

- ^ Le Monde, Pour le rôle de la SNCF dans la Shoah, Paris va verser 100 000 euros à chaque déporté américain [1]

- ^ Henley, Jon (2003-03-03). "French court strikes blow against fugitive Nazi". London: The Guardian. Retrieved 2014-02-06.

France condemned Brunner to death in absentia in 1954 for crimes against humanity. He is still wanted.

- ^ a b NAAF Holocaust Project Timeline 1943 Continued. NeverAgain.org.

- ^ Yitschak Kerem, Le Monde sépharade, Volume I, p. 924–933. Paris: Éditions du Seuil, 2006. ISBN 2020869926.

- ^ a b Deportations to Killing Centers

- ^ a b Steven Bowman (2002). "The Jews in Greece" (PDF file, direct download). Minorities in Greece: Aspects of a Plural Society. University of Cincinnati: 9 of current document (427). Retrieved 18 February 2014.

- ^ Peter Vogelsang & Brian B. M. Larsen (2002). "Deportations from the Balkans". Holocaust Education: Deportations. The Danish Center for Holocaust and Genocide Studies. Retrieved 18 February 2014.

- ^ Librarian (10 Sep 2006), Hungarian military in WWII. Bulletin, Senta, Serbia.

- ^ a b Naftali Kraus, Holocaust Period. Jewish History of Hungary.

- ^ Naftali Kraus (2014). "Jewish History of Hungary". Porges.net. Retrieved 24 February 2014.

- ^ "Deportations to Killing Centers: Central Europe". Holocaust Encyclopedia. United States Holocaust Memorial Museum, Washington, DC. May 11, 2012. Retrieved 24 February 2014.

- ^ Yad Vashem, Hungarian Jewry at Holocaust History.

- ^ a b Rebecca Weiner, Hungary Virtual Jewish History Tour Jewish Virtual Library.

- ^ David Kranzler, The Man Who Stopped the Trains to Auschwitz: George Mantello, El Salvador, and Switzerland's Finest Hour. [page needed]

- ^ Bridge, Adrian (1996-09-05). "Hungary's Jews Marvel at Their Golden Future". London: The Independent. Retrieved 2014-02-27.

- ^ Peter Vogelsang & Brian B. M. Larsen, Deportations. The Danish Center for Holocaust and Genocide Studies.

- ^ a b Braham, p.48; Bauer, p.197.

- ^ a b c Hilberg, Raul. The Destruction of the European Jews, Yale University Press, 2003, p. 903

- ^ Braham, Randolph (2004): Rescue Operations in Hungary: Myths and Realities, East European Quarterly 38(2): 173–203.

- ^ Bauer, Yehuda (1994): Jews for Sale?, Yale University Press, ISBN 0-300-05913-2.

- ^ Bilsky, Leora (2004): Transformative Justice : Israeli Identity on Trial (Law, Meaning, and Violence), University of Michigan Press, ISBN 0-472-03037-X

- ^ The mystery of the Hungarian 'gold train'. Eyelatch/Iwaniec Associates

- ^ a b The Mystery of the Hungarian "Gold Train" Jewish Virtual Library.

- ^ "Gold Train" Settlement Will Fund Services for Hungarian Holocaust Survivors; Objections, Exclusions Due August 1, 2005.

- ^ a b Bridget Kevane (June 29, 2011). "A Wall of Indifference: Italy's Shoah Memorial". The Jewish Daily Forward.com. Retrieved 16 April 2014.

- ^ a b Egill Brownfeld (Fall 2003). "The Italian Holocaust: The Story of an Assimilated Jewish Community". Jewish Fascists and Anti-Fascists. The American Council For Judaism. Retrieved 16 April 2014.

- ^ a b Franklin Hugh Adler (Winter 2006). "The Civilization of the Holocaust in Italy: Poets, Artists, Saints, Anti-Semites by Wiley Feinstein". Book review. Holocaust and Genocide Studies. Retrieved 16 April 2014.

- ^ Holocaust Encyclopedia (June 10, 2013). "Southern Europe". Deportations to Killing Centers. United States Holocaust Memorial Museum. Retrieved 16 April 2014.

- ^ a b Frontline, Switzerland: The Train. PBS.org

- ^ Jewish Virtual Library, Netherlands (Holland): The Holocaust Era. Encyclopedia Judaica.

- ^ Yad Vashem, Deportation train from Westerbork, Holland. Photo Archives 43253.

- ^ a b Van der Boom (1 May 2007), Holocaust in the Netherlands: 'We really had no idea'. Leiden University. Review of Tegen beter weten in by Ies Vuijsje's.

- ^ Holocaust Encyclopedia, Westerbork. United States Holocaust Memorial Museum, Washington, D.C.

- ^ Schelvis, Jules (1993). Vernietigingskamp Sobibor (in Dutch) (5th. (2004) ed.). De Bataafsche Leeuw. pp. 236ff. ISBN 9789067076296.

- ^ a b BBC - Birmingham - Faith - The Last Train from Belsen

- ^ "Like a slow train coming". Expatica.com. Archived from the original on 2007-12-11.

- ^ a b c d Jerzy Wasilewski (2014). "25 września. Wcielenie kolei polskich na Śląsku, w Wielkopolsce i na Pomorzu do niemieckich kolei państwowych Deutsche Reichsbahn". Polskie Koleje Państwowe PKP. Retrieved 8 February 2014.

- ^ a b c d Teresa Masłowska (2 September 2007). "Wojenne Drogi Polskich Kolejarzy" (PDF file, direct download 644 KB). Czy wiesz, że... Kurier PKP No 35 / 2007. p. 13. Retrieved 8 February 2014.

- ^ PAP (14 October 2014). "W Gdyni odsłonięto pomnik wysiedlonych przez niemieckich okupantów" [Monument unveiled in Gdynia to victims of Nazi German expulsions]. Dzieje.pl.

- ^ Anna Machcewicz (16 February 2010). "Mama wzięła ino chleb" [Mom took only the bread]. Historia. Tygodnik Powszechny. Retrieved 31 January 2016.

- ^ Simone Gigliotti (2009). Resettlement. Berghahn Books. p. 55. ISBN 184545927X. Retrieved 21 September 2015.

{{cite book}}:|work=ignored (help) - ^ Alfred C. Mierzejewski (Jun 19, 2003). Most Valuable Asset of the Reich: A History of the German National Railway 1933-1945. Univ. of North Carolina Press. pp. 78–80. Retrieved 9 February 2014.

{{cite book}}:|work=ignored (help) - ^ Hans Pottgiesser (1975) [1960]. Die Deutsche Reichsbahn im Ostfeldzug 1939 - 1944. Kurt Vowinkel Verlag. pp. 17–18.

Excerpts.

{{cite book}}: External link in|quote= - ^ "The unloading ramps and selections". Auschwitz-Birkenau State Museum.

Transports of Poles from Warsaw during the Uprising there, sent to Auschwitz by way of the transit camp in Pruszków, were unloaded at the third ramp built in 1943 inside Birkenau.

- ^ CSRO (2010). "Pierwszy Transport do KL Auschwitz: 14 Czerwca 1940" [The First Transport]. Narodowy Dzień Pamięci Ofiar Nazistowskich Obozów Koncentracyjnych. Chrześcijańskie Stowarzyszenie Rodzin Oświęcimskich. Państwowe Muzeum Auschwitz - Birkenau.

- ^ Andrew Rawson (2015). Auschwitz: The Nazi Solution. Pen and Sword. p. 29. ISBN 1473855411.

- ^ Robert Gellately. Revieved works: Vom Generalplan Ost zum Generalsiedlungsplan by Czeslaw Madajczyk. Der "Generalplan Ost." Hauptlinien der nationalsozialistischen Planungs- und Vernichtungspolitik by Mechtild Rössler; Sabine Schleiermacher. Central European History, Vol. 29, No. 2 (1996), pp. 270–274

- ^ Madajczyk, Czesław. "Die Besatzungssysteme der Achsenmächte. Versuch einer komparatistischen Analyse." Studia Historiae Oeconomicae vol. 14 (1980): pp. 105-122 [1] in Hitler's War in the East, 1941–1945: A Critical Assessment by Gerd R. Uebersch̀ear and Rolf-Dieter Müller

- ^ Berghahn, Volker R. (1999). "Germans and Poles 1871–1945". in Germany and Eastern Europe: Cultural Identities and Cultural Differences (Rodopi), pp. 15-34; ISBN 9042006889.

- ^ Hitler's War; Hitler's Plans for Eastern Europe. Warsaw: Polonia Publishing House. 1961. pp. 7–33, 164–178 – via Internet Archive from Northeastern University Holocaust Awareness Committee.

{{cite book}}:|work=ignored (help); Unknown parameter|authors=ignored (help) - ^ Norman Davies (1982). Polenlagers. Columbia University Press. p. 338. ISBN 0199253404. Retrieved 2 February 2016.

{{cite book}}:|work=ignored (help) - ^ Agnieszka Jaczyńska (2012). Aktion Zamosc (PDF). OBEP IPN, Lublin: Institute of National Remembrance. 30-35 (1-5 in PDF). Retrieved 2 February 2016.

{{cite book}}:|work=ignored (help) - ^ Paweł Brojek (2014). "Niemieckie wysiedlenia Polaków z Zamojszczyzny. Zabili 10 tys. dzieci" [German deportations of Poles from the Zamość region. Ten thousand children killed]. Prawy.pl - Portal poświęcony Polsce, rodzinie i tradycji.

- ^ Czesław Madajczyk: Zamojszczyzna – Sonderlaboratorium SS t. 1–2. Warszawa: 1979

- ^ Biuletyn IPN nr 40 (5)/2004. Instytut Pamięci Narodowej, IPN, ISSN 1641-9561

- ^ Krystian Brodacki (2001-06-25). "Co z tymi napisami?". W 1942 roku w Krakowie. Nasza Witryna, reprint from Tygodnik Solidarność. Retrieved 8 February 2014.

- ^ Ireneusz Bujniewicz (2009). "Możliwości finansowe PKP w przebudowie i rozbudowie kolejnictwa" (PDF file, direct download 363 KB). Kolejnictwo w przygotowaniach obronnych Polski w latach 1935–1939. Wydawnictwo Tetragon Publishing. p. 22. Retrieved 8 February 2014.

- ^ Michał Kubara, Beata Mamcarczyk, Marcin Paździora, Sandra Schab (2012). Sosnowiec (PDF file, direct download 9.97 MB). Zagłębiowska Oficyna Wydawnicza Publishing. pp. 84–85. ISBN 978-83-928381-1-1. Retrieved 9 February 2014.

{{cite book}}:|work=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Edward Kopówka (2011), "Treblinka II (Monograph, chapt. 3)" (PDF, direct download 20.2 MB), Dam im imię na wieki [I will give them an everlasting name. Isaiah 56:5] (in Polish), Drohiczyńskie Towarzystwo Naukowe [The Drohiczyn Scientific Society], p. 97, ISBN 978-83-7257-496-1, retrieved 9 February 2014

- ^ "Aktion Reinhard" (PDF). Yad Vashem Shoah Resource Center, The International School for Holocaust Studies.

See: 'Aktion Reinhard' named after Reinhard Heydrich, the main organizer of the "Final Solution"; also, Treblinka, 50 miles northeast of Warsaw, set up June/July 1942.

- ^ Robert Moses Shapiro. Holocaust Chronicles. Published by KTAV Publishing Inc. 1999 ISBN 0-88125-630-7, 302 pages. Retrieved 5 February 2014.

... the so-called Gross Aktion of July to September 1942... 300,000 Jews murdered by bullet of gas (page 35).

- ^ "Holocaust Remembrance Day in Warsaw". Retrieved 5 February 2014.

- ^ Kopówka, Edward; Rytel-Andrianik, Paweł, "Treblinka II – Obóz zagłady (Treblinka II Death Camp)" (PDF), Monograph, chapt. 3: ibidem, Drohiczyńskie Towarzystwo Naukowe, p. 94, ISBN 978-83-7257-496-1 – via Drohiczyn Scientific Society, direct download 20.2 MB.

{{citation}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - ^ Holocaust Encyclopedia (10 June 2013). "Warsaw Ghetto Uprising". US Holocaust Memorial Museum. Archived from the original on 2 May 2012. Retrieved 25 August 2013.

- ^ Jacek Małczyński (2009-01-19). "Drzewa "żywe pomniki" w Muzeum – Miejscu Pamięci w Bełżcu [Trees as living monuments at Bełżec]". Współczesna przeszłość, 125-140, Poznań 2009. University of Wrocław. pp. 39–46. Retrieved 8 August 2013.

- ^ Paweł Reszka (Dec 23, 2005). "Majdanek Victims Enumerated. Changes in the history textbooks?" (Internet Archive). Gazeta Wyborcza. Auschwitz-Birkenau State Museum. Retrieved April 29, 2013.

- ^ Raul Hilberg (1985), The Destruction of the European Jews by Yale University Press, p. 1219. ISBN 978-0-300-09557-9, versus Thomas Blatt (1983), Sobibor - The Forgotten Revolt by H.E.P., pp. 3, 92; ISBN 0964944200

- ^ Holocaust Encyclopedia, "Treblinka" United States Holocaust Memorial Museum.

- ^ Jennifer Rosenberg (1998). "The Lódz Ghetto: History & Overview (1939 - 1945)". Jewish Virtual Library. Retrieved 8 February 2014.

- ^ Adam Dyląg. "Barwałd: W rocznicę tragicznych wydarzeń". Archiwum: W rocznicę tragicznych wydarzeń. Portal dwutygodnika Wolna Droga - Pismo Sekcji Krajowej Kolejarzy. Retrieved 10 February 2014.

- ^ J. Studnicki; et al. (2011-10-20). "1944-11-24, Barwałd Średni (śląskie)". Największe katastrofy kolejowe. Towarzystwo Kontroli Rekordów Niecodziennych. Retrieved 8 February 2014.

- ^ a b "Report of the International Commission on the Holocaust in Romania". Yad Vashem. November 11, 2004. Retrieved 2014-02-27.

- ^ Marcu Rozen (2006). "The Holocaust under the Antonescu government". Association of Romanian Jews Victims of the Holocaust (A.R.J.V.H.). Retrieved 2014-02-27.

- ^ "Holocaust in Podu Iloaiei, Romania".

- ^ Holocaust Encyclopedia. "Norway". United States Holocaust Memorial Museum. Roundups of Norwegian Jews. Retrieved 20 January 2016.

Photographs of two deportation ships: SS Donau and SS Monte Rosa, courtesy of Oskar Mendelsohn.

{{cite web}}: External link in|quote= - ^ "The Fate of the Slovak Jews". Holocaust Research Project.org. 2008. Sources: G. Reitlinger, Avigdor Dagan, Raul Hilberg, Israel Gutman, Yitzhak Arad, OMDA Archives. Retrieved 20 January 2016.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|authors=ignored (help) - ^ a b Markus G. Jud, Switzerland's Role in World War II at History of Switzerland.

- ^ Markus G. Jud, Looted Assets, Gold Transactions and Dormant Accounts at Switzerland during World War II.

- ^ a b Switzerland at Yad Vashem International School for Holocaust Studies.

- ^ a b David Marks, The Train, BBC Frontline

- ^ The Avalon Project: The Versailles Treaty June 28, 1919 at www.Yale.edu