Liao dynasty

Khitan Empire | |||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 907–1125 | |||||||||||||||||

Location of the Liao Dynasty in the year 1111 (purple) | |||||||||||||||||

| Capital | Shangjing1 | ||||||||||||||||

| Common languages | Middle Chinese, Khitan | ||||||||||||||||

| Religion | Buddhism, Khitan traditional animism, influences from Taoism and others | ||||||||||||||||

| Government | Monarchy | ||||||||||||||||

| Emperor | |||||||||||||||||

• 916-926 | Taizu | ||||||||||||||||

• 926-947 | Taizong | ||||||||||||||||

• 947-951 | Shizong | ||||||||||||||||

• 951-969 | Muzong | ||||||||||||||||

• 969-982 | Jingzong | ||||||||||||||||

• 982-1031 | Shengzong | ||||||||||||||||

• 1031–1055 | Xingzong | ||||||||||||||||

• 1055–1101 | Daozong | ||||||||||||||||

• 1101-1125 | Tianzuo | ||||||||||||||||

| History | |||||||||||||||||

• Abaoji becomes the Khitan Great Khan | 907 | ||||||||||||||||

• Abaoji assumes the title of Celestial Emperor | 916 | ||||||||||||||||

• "Greater Liao" is adopted as a dynastic name | 947 | ||||||||||||||||

• Liao and Song Dynasties sign the Chanyuan Treaty | 1005 | ||||||||||||||||

• Emperor Tianzuo is captured by the Jin | 1125 | ||||||||||||||||

| Area | |||||||||||||||||

| 947 est.[1] | 2,600,000 km2 (1,000,000 sq mi) | ||||||||||||||||

| 1111 est. | 4,000,000 km2 (1,500,000 sq mi) | ||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||

1. Shangjing was the first of five capitals that were established, all of which served concurrently as regional capitals. | |||||||||||||||||

| Part of a series on the |

| History of China |

|---|

The Liao Dynasty (Khitan: Mos Jælud; Mongolian: Лиао Улс; simplified Chinese: 辽朝; traditional Chinese: 遼朝; pinyin: Liáo Cháo;),[2] also known as the Khitan Empire (Khitan: Mos diau-d kitai huldʒi gur; Mongolian: Хятан Гүрэн, Кидан Гүрэн; simplified Chinese: 契丹国; traditional Chinese: 契丹國; pinyin: Qìdān Guó),[3] was an empire in East Asia that ruled over Mongolia and portions of the Russian Far East, northern Korea, and northern China proper from 907 to 1125. It was founded by the Khitan Great Khan Abaoji around the time of the collapse of the Han Chinese Tang Dynasty. Almost immediately after its founding, the Liao Dynasty began a process of territorial expansion, with its founder Abaoji leading a successful conquest of the Bohai. Later emperors would gain sixteen Chinese prefectures by fueling a proxy war that led to the collapse of the Tang Dynasty, and would make both the Goryeo and the Song Dynasty into tribute states following successful military campaigns into their territories.

Tension between traditional Khitan social and political practices and Chinese customs was a defining feature of the dynasty. This tension led to a series of succession crises; Liao emperors favored the Chinese concept of primogeniture, while much of the rest of the Khitan elite supported the traditional method of succession by the strongest candidate. So different were Khitan and Chinese practices that Abaoji set up two parallel governments. The Northern Administration governed Khitan areas following traditional Khitan practices, while the Southern Administration governed areas with large non-Khitan populations, adopting traditional Chinese governmental practices. Differences between Chinese and Khitan society included gender roles and marital practices: the Khitans took an egalitarian view towards gender, in sharp contrast to Chinese cultural practices that placed women as subservient to men. Khitan women were taught to hunt, managed family property, and held military posts. Many marriages were not arranged, women were not required to be virgins until their first marriage, and women had the right to divorce and remarry.

The Liao Dynasty was destroyed by the Jurchen people of the Jin Dynasty in 1125, with the Jin capture of Liao emperor Tianzuo. However, remnants of its people, led by Yelü Dashi, established the Western Liao Dynasty, also known as the Kara-Khitan Khanate, which ruled over parts of Central Asia for almost a century before being conquered by the army of the Mongolian ruler Genghis Khan. Although cultural achievements associated with the Liao Dynasty are considerable, and a number of various statuary and other artifacts exist in museums and other collections, major questions remain over the exact nature and extent of the influence of the Liao Khitan culture upon subsequent developments, such as the musical and theatrical arts.

History

Khitans before Abaoji

Neither the origins, ethnic makeup, nor early history of the Khitans are well documented in historical records.[4] The earliest reference to a Khitan state is found in the Book of Wei, a history of the Northern Wei Dynasty (386–534) that was completed in 554.[5] Several books written after 554 mention the Khitans as being active during the late third and early fourth centuries. The Book of Jin (648), a history of the Jin Dynasty (265–420), refers to the Khitans in the section covering the reign of Murong Sheng (398–401). Samguk Sagi (1145), a history of the Three Kingdoms of Korea, mentions a Khitan raid taking place in 378.[6]

According to sinologists Denis C. Twitchett and Klaus-Peter Tietze, it is generally held that the Khitans emerged from the Yuwen branch of the Xianbei people. Following a defeat at the hands of another branch of the Xianbei in 345, the Yuwen split into three tribes, one of which was called the Kumo Xi. In 388 the Kumo Xi itself split, with one group remaining under the name Kumo Xi and the other group becoming the Khitans.[5] This view is partially backed up by the Book of Wei, which describes the Khitans as being of Xianbei origins.[5] There are also several competing theories on the origin of the Khitans. Beginning in the Song Dynasty, some Chinese scholars suggested that the Khitans might have descended from the Xiongnu people. While modern historians have rejected the idea that the Khitan were solely Xiongnu in origin, there is some support for the claim that they are of mixed Xianbei and Xiongnu origin. Beginning with Rashid-al-Din Hamadani in the fourteenth century, several Western scholars have theorized that the Khitans were Mongolic in origin, and in the late 19th century Western scholars made the claim that the Khitans were Tungusic in origin -- modern linguistic analysis has discredited this claim.[7]

By the time the Book of Wei was written in 554, the Khitans had formed a state in what is now China's Jilin and Liaoning Provinces.[5] The Khitans suffered a series of military defeats to other nomadic groups in the region, as well as to the Chinese Northern Qi and Sui Dynasties. Khitan tribes at various times fell under the influence of Turkic tribes such as the Uighurs and Chinese dynasties such as the Sui and Tang. This influence would significantly shape Khitan language and culture.[8] For most of the century between 630 and 730, the Khitans were under the influence of the Tang Dynasty. The arrangement was largely the doing of the Khitan Dahe clan. The Tang emperor bestowed the Chinese surname Li on the Dahe and appointed their leader to a governorship that Twitchett and Tietze described as "an office specifically created for the indirect management of the Khitan tribes".[9] Towards the turn of the century, however, Tang control of the north began to slip as it focused attention on its other borders. In 696 the Dahe leader, Li Jinzhong, launched a rebellion and led Khitan forces into Hebei. Although the rebellion was defeated, it took over fifteen years before the Tang were able to reassert control over the Khitans, and that control would never be strong or long-lived. Re-disintegration of Khitan-Liao relations in the 730s saw the Yaolian clan replace the Dahe as the Khitan ruling clan, forcing Tang governor An Lushan to launch two invasions into Khitan territory in 751 and 755. After being soundly defeated by the Khitans during the first invasion, An Lushan was successful in the second, but he then led a rebellion against the Tang that included Khitan troops in his army. The An Lushan Rebellion marked the beginning of the end of the Tang Dynasty.[10]

Following the An Lushan Rebellion, the Khitans became vassals of the Uighurs, while simultaneously paying tributes to the Tang, a situation that lasted from 755 until the fall of the Uighurs in 840. From 840 until the rise of Aboji, the Khitans remained a tributary of the Tang Dynasty.[11]

Abaoji and the rise of the Khitans

| History of Mongolia |

|---|

|

Abaoji, who later became Emperor Taizu of Liao, was born in 872, the son of the chief of the Yila tribe. At that time, the Yila tribe was the largest and strongest of the eight affiliated Khitan tribes; however, the Great Khan, the overall leader of the Khitans, was drawn from the Yaolian lineage. In 901 Abaoji was elected to be the chief of the Yila tribe by its tribal council. By 903, Abaoji had been named the Yüyue, the overall military leader of the Khitans, subordinate only to the Great Khan. Four years later, in 907, Abaoji became the Great Khan of the Khitans, ending nine generations of Yaolian rule.[12] Abaoji acquired the prestige needed to secure the position of Khitan Great Khan through a combination of effective diplomacy and a series of successful military campaigns, beginning in 901, against the Han Chinese forces to the south, the Xi and Shiwei to the west, and the Jurchens in the east.[12]

The same year that Abaoji became Great Khan, the Chinese warlord Zhu Wen, who in 904 had murdered the last legitimate emperor of the Tang Dynasty, declared the Tang over and named himself emperor of China. His dynasty dissolved quickly, ushering in the fifty-three-year period of disunity known as the Five Dynasties period. One of the five dynasties, the Later Jin Dynasty (936–947), was a client state of the Khitans.[13]

For much of Chinese history, the position of Emperor was determined by primogeniture; the position would pass from father to first-born son upon the father's death. While Khitan succession was also kept within families, an emphasis was placed on selecting the most capable option, with all of a leader's brothers, nephews, and sons considered valid choices for succession. Khitan rulers were expected to hand over power to a paternal relative after serving a single three-year term.[14] Abaoji signaled his desire to become a permanent ruler in 907, securing his position by killing most of other Khitan chieftains.[15] Between 907 and 910 Abaoji's rule went unchallenged. It was only after 910, when Abaoji disregarded the Khitan tradition that another member of the family assume the position of Great Khan, that his rule came under direct challenge. In both 912 and 913 members of Abaoji's family, including most of his brothers, attempted armed insurrections. After the first insurrection was discovered and defeated, Abaoji pardoned the conspirators. After the second, only his brothers were pardoned, with the other conspirators suffering violent deaths. The brothers plotted additional rebellions in 917 and 918, both of which were easily crushed.[16]

In 916, at what would have been the end of his third term as Khitan Grand Khan, Abaoji made a number of changes moving the Khitan state closer to the model of governance used by the Chinese dynasties. He assumed the title of Celestial Emperor and designated an era name, named his oldest son Yelü Bei as his successor, and commissioned the construction of a Confucian temple. Two years later he established a capital city, Shangjing (上京), which imitated the model of a Chinese capital city.[17]

Before his death in 926, Abaoji greatly expanded the areas that the Khitans controlled.[18] At its height, the Liao Dynasty encompassed modern-day Mongolia, parts of Kazakhstan and the Russian Far East, and the Chinese provinces of Hebei, Heilongjiang, Inner Mongolia, Jilin, Liaoning, and Shanxi.[19]

Succession issues and the occupation of Kaifeng

In 916 Emperor Taizu (Abaoji) officially designated his eldest son, Yelü Bei, as his successor.[20] Succession by primogeniture was a long-held standard in Chinese culture but was not accepted among the Khitans, creating a friction between Taizu's desires and the beliefs of the Khitan elites, including Taizu's wife, Empress Shulü Ping. Taizu, sensing the possibility that the succession process would run into difficulty, forced the Khitan leadership to swear allegiance to Yelü Bei after he was installed as heir apparent. To the Khitans, this was considered a radical move.[21] This friction between primogeniture and succession by the strongest candidate would lead to repeated succession crises, the first of which occurred after Taizu's sudden and unexpected death in 926.[22]

Yelü Bei was twenty-six years old at the time of his father's death. A polymath, Bei exemplified many of the values of the Chinese aristocracy; he was an expert in music, medicine, fortune-telling, painting, and writing (in both Chinese and Khitan).[23] He was also an accomplished warrior, leading troops into battle during his father's conquest of Bohai. After the campaign ended in victory for the Liao in 926, Emperor Taizu gave Bei command of the conquered territory––which became known as the principality of Dongdan––as well as the title of Prince of Dongdan.[24]

Empress Shulü Ping, who became known as Empress Dowager Yingtian following the death of her husband, was an exceptionally powerful figure both before and after Taizu's death. While the latter was alive, Shulü Ping commanded an army of 200,000 horsemen that was tasked with maintaining order while Taizu led military campaigns abroad. She also led campaigns herself. Following the death of her husband, the Empress rejected the traditional Khitan custom of being buried with him, and elected to cut off her right hand and bury that with the Emperor instead. Shulü Ping then seized full military and civil authority in order to oversee the imperial succession under her own terms.[23] The Empress's refusal to kill herself and be buried with Taizu effectively ended the longstanding custom.[25]

Precisely because Prince Yelü Bei exemplified both Chinese and Khitan values, Empress Shulü Ping objected to Bei assuming the role of Emperor. The Empress believed that Bei's openness to Chinese culture detracted from his leadership ability as a Khitan, and she instead favored Emperor Taizu's more traditionalist second son, Yelü Deguang. Deguang enjoyed not only the support of his mother, but also of the Khitan nobility. Realizing that he could not assume the throne, and that it would be dangerous to try, Bei campaigned in favor of allowing his younger brother to assume the throne, and by the end of 927, formally stated to his mother that Deguang's qualifications were superior to his own, functionally ending his ability to challenge Deguang's ascension to the throne.[26]

Despite Bei voluntarily relinquishing his claim, Deguang, who had assumed the title of Emperor Taizong of Liao, viewed Bei as a threat. Bei still held the role of Prince of Dongdan, and moved back there after relinquishing his imperial claim. In order to break any potential power base Bei might form in Dongdan, Emperor Taizong ordered that the capital of Dongdan and all of its people move to what is now Liaoyang.[27] Prince Bei himself was placed under surveillance by the Emperor.[21] In 930 Prince Bei fled to the Later Tang Dynasty, where he became an honored guest of Emperor Mingzong, who went as far as to bestow upon Prince Bei the Emperor's own surname of Li (李).[21] There are two conflicting accounts of Prince Bei's death: he was assassinated either in 936 by Emperor Mo of Later Tang in retaliation for the Khitans' support in overthrowing the Tang and replacing it with the Later Jin Dynasty, or in 937 by Emperor Gaozu of Later Jin (Shi Jingtang) as a show of loyalty to Emperor Taizong of Liao.[27]

After Emperor Mingzong died in 933, the Later Tang Dynasty began to crumble from its own succession crisis. Mingzong's son and successor Li Conghou ruled for only five months before he was killed in 934 in a coup led by his adoptive brother Li Siyuan (Emperor Mo of Later Tang). Prince Bei, who was still an honored guest at the Tang court at the time, wrote to his brother Emperor Taizong (Yelü Deguang), advising him to invade the Tang. Instead, Taizong lent military support to a rebellion led by Shi Jingtang, a Tang governor and son-in-law of the former Emperor Mingzong. With Khitan help, in 936 Shi Jingtang succeeded in replacing the Later Tang with his own Later Jin Dynasty.[28] After some negotiation with the more powerful Khitans, he ceded sixteen border prefectures stretching from modern-day Datong (Shanxi province) to the coast of the Bohai Sea east of what is now Beijing, to the Liao.[29] Since the Sixteen Prefectures contained numerous strategic passes and fortifications, the Khitans now had unrestricted access to the plains of northern China.[30] Shi Jingtang also agreed to treat Emperor Taizong of Liao as his own father, a move that symbolically elevated Taizong and the Liao to a superior position.[28]

The relationship between the Liao and the Later Jin soured after the death of Shi Jingtang in 942 and the elevation to the throne of Shi Chonggui, also known as Emperor Chudi of Later Jin. The new emperor surrounded himself with anti-Khitan advisers, and in 943 he expelled the Liao envoy from the Jin capital of Kaifeng and seized the property owned by Khitan merchants in the city. By the end of the following year Emperor Taizong had launched an invasion of the Jin. Although the invasion took three years and the Liao faced several setbacks, by the end of 946 Emperor Taizong had secured the surrender of the head of the Later Jin forces and was able to march into Kaifeng unopposed.[31] Emperor Taizong celebrated his victory with the adoption of the dynastic name "Greater Liao".[32] The invading Liao forces, who had not brought adequate supplies for their invasion, began looting the newly conquered territory and imposed high taxes on the ethnic Chinese population in the formerly Jin lands. This sparked a series of rebellions that culminated in 947 with the establishment of the Later Han Dynasty by the former Jin governor Liu Zhiyuan. After occupying Kaifeng for only three months, Emperor Taizong and the Liao were forced to retreat north. During the retreat Emperor Taizong died of a sudden illness, just south of modern day Shijiazhuang, Hebei.[31]

The death of Taizong set up a second succession crisis, again instigated by Empress Dowager Yingtian and fueled by the conflict between Chinese primogeniture and Khitan succession customs. Yelü Ruan, oldest son of Prince Bei and nephew of Emperor Taizong, proclaimed himself Emperor while still in Hebei. Emperor Taizong raised Yelü Ruan, following Yelü Bei's departure for the Later Tang Dynasty, and the relationship between uncle and nephew was close. Yelü Ruan accompanied the emperor during his invasion of the Later Jin Dynasty, and he earned the reputation as a capable warrior and commander, and as one of courteous and noble-minded disposition. Empress Dowager Yingtian supported Emperor Taizong's younger brother, Yelü Lihu, for the throne instead. The Empress Dowager sent two successive armies to face Yelü Ruan, who defeated them both. Ultimately Lihu, who the Khitan nobility viewed as cruel and spoiled, was unable to gain enough support to further challenge Yelü Ruan, and after a peace was brokered by a cousin of the Yelü clan, Yelü Ruan formally assumed the role of emperor and the title of Emperor Shizong of Liao. Emperor Shizong promptly exiled both Empress Dowager Yingtian and Yelü Lihu from the capital, ending their political ambitions.[33] Emperor Shizong's rule would be characterized by a series of rebellions from within his extended family. Although he would rule for only four years before being killed in 951 in a rebellion led by one of his nephews, Emperor Shizong oversaw a refinement of his grandfather's dual system of government, which brought the structure of the Southern Administration closer to the model used by the Tang Dynasty.[34] Emperor Shizong would be succeeded by Emperor Taizong's son Yelü Jing, also known as Emperor Muzong of Liao. Emperor Muzong, who died in 969, would be the second and the last of the emperors to succeed Abaoji who was not a direct descendant of Yelü Bei.[25]

Emperor Shengzong and the height of Liao power

The reign of Emperor Shengzong from 982 to 1031 represented the height of the Liao Dynasty's power.[35][36] Shengzong oversaw successful military campaigns against the Chinese Song Dynasty and the Korean Goryeo Dynasty, and both campaigns secured long-term peace agreements with terms favorable to the Liao.

Submission of the Goryeo

When Abaoji conquered the Bohai state in 926, most of the population was relocated to the area that is now Liaoning, China. At least three groups remained in the former Bohai territory, one of which formed the state of Dingan. Despite launching two invasions, in 975 and 985, the Liao were unable to defeat the Dingan. Unable to eliminate the threat, and weary of Jurchen groups also inhabiting the region, the Liao established three forts with military colonies in the Yalu River valley area.[37]

These military actions so close to Goryeo territory, combined with a cancelled Liao invasion of Goryeo in 947 and a strong diplomatic and cultural relationship between the Goryeo and Song Dynasties, caused Liao-Goryeo relations to be exceedingly poor. Both the Liao and the Goryeo saw each other as posing a military threat; the Liao feared that the Goryeo would attempt to foment rebellions among the Bohai population in Liao territory, while the Goryeo feared invasion by the Liao. The Liao did invade Goryeo in 992, sending a force that the Liao commander claimed to be 800,000 strong, and demanding that the Goryeo cede to the Liao several territories surrounding the Yelu River. The Goryeo appealed for assistance from the Song Dynasty, with which they had a military alliance, but no Song assistance came. The Liao made steady southward progress before reaching the Ch'ongch'on River, at which point they called for negotiations between the Liao and Goryeo military leaders. While the Liao initially demanded total surrender from the Goryeo, and the Goryeo initially appeared willing to consider it, the Korean negotiator was eventually able to convince the Liao to accept a resolution in which the Goryeo Dynasty became a tributary state to the Liao.[38] By 994, regular diplomatic exchanges between the Liao and Goryeo began, and the relationship between the Goryeo and the Song irrevocably chilled.[39]

The peace did not last two decades. In 1009 the Goryeo general Gang Jo murdered King Mokjong of Goryeo and put King Hyeonjong of Goryeo on the throne with the intention of serving as the boy's regent. The Liao immediately sent an army of 400,000 men to Goryeo to punish Gang Jo; however, after an initial period of military success and the breakdown of several attempts at peace negotiations, the Goryeo and Liao entered a decade of continuous warfare. In 1018 the Liao faced the most significant military defeat in the dynasty's history, but by 1019 they had already assembled another large army to march on the Goryeo. At this point both sides realized that they could not defeat each other militarily, so in 1020 King Hyeonjong resumed sending tributes to the Liao, and in 1022 the Liao officially recognized the validity of King Hyeonjong's reign. Goryeo would remain a vassal, and the relationship between the Liao and Goryeo would remain peaceful until the end of the Liao Dynasty.[40]

The Song Dynasty and the Chanyuan Treaty

In 951, the Later Zhou Dynasty emerged, the last of the five short-lived dynasties making up the Five Dynasties and Ten Kingdoms period. The founding emperor of the Later Zhou died in 954 and was succeeded by his adopted son, who would rule with the name Emperor Shizong of Later Zhou. Shizong believed that the Liao Dynasty was poised to invade the Zhou, and in 958 he launched a preemptive military campaign against the Liao, aiming to take the sixteen prefectures ceded to the Liao by Emperor Gaozu of Later Jin in 938. Emperor Shizong died in 959, before his army had even met the Liao forces. In 960 the commander-in-chief of the Later Zhou palace guard, Zhao Kuangyin, usurped the throne, then occupied by Emperor Shizong's seven-year-old son, and proclaimed himself the founder of the Song Dynasty.[41]

Relations between the Liao and the Song were initially peaceful, with the two dynasties exchanging embassies in 974.[42] Following the collapse of the Tang Dynasty, several territories formed small, independent states that were never reunified during the Five Dynasties and Ten Kingdoms period. Additionally, several additional territories that were controlled by military governors during the Tang Dynasty had fallen under the control of local warlords following the Tang collapse. Rather than focus on reclaiming land from the Liao Dynasty, Zhao Kuangyin, who would take the title Emperor Taizu of Song, focused on reclaiming these smaller break-off territories. He would die in 976 having reestablished control over all but one of these territories, the Northern Han kingdom. Despite the Northern Han's status as a protectorate of the Liao Dynasty, Emperor Taizu of Song launched an invasion of the kingdom in 976, only months before his death. The Northern Han received assistance from the Liao, and the invasion was repelled. Emperor Taizong of Song, brother of the founding emperor and the second emperor of the Song Dynasty, launched a second invasion in 979. The Northern Han again received Liao assistance, but this invasion was successful; the Northern Han crumbled, and the Song were able to assume control of the territory.[42] Emperor Taizong of Song immediately followed this victory with an attempted invasion of the sixteen prefectures, but the unrested and undersupplied Song troops were thoroughly routed by the Liao in the Battle of Gaoliang River.[42]

Over the next two decades, the relationship between the Liao and Song continued to deteriorate. The Liao were continuously informed of Song attempts to create military alliances with other groups sharing a border with the Liao, and minor border skirmishes were common. Beginning in 999 Emperor Shengzong of Liao led a series of campaigns against the Song that, while generally successful on the battlefield, failed to secure anything of value from the Song. This changed in 1004 when Emperor Shengzong led a campaign that rapidly worked its way to right outside of the Song capital of Kaifeng by only conquering cities that quickly folded to the Liao army, while avoiding protracted sieges of the cities that resisted heavily. Emperor Zhenzong of Song marched out and met the Liao at Chanyuan, a small city on the Yellow River. In January 1005 the two dynasties signed the Chanyuan Treaty, which stipulated that the Song would give the Liao 200,000 bolts of silk and 100,000 ounces of silver each year, that the two emperors would address each other as equals, that they would finalize the location of their disputed border, and that the two dynasties would resume cordial relations. While the sums (referred to as gifts by the Song and as tributes by the Liao) were later increased to 300,000 bolts of silk and 200,000 ounces of silver per year out of Song fears that the Liao might form a military alliance with the Western Xia, no major wars were fought between the Liao and Song for over a century following the signing of the treaty.[43] By signing the treaty the Song Dynasty functionally ceded its claim over the sixteen prefectures.[44]

Imperial infighting

Emperor Shengzong died in 1031, leaving behind instructions that named his son Yelü Zongzhen as heir. Yelü Zongzhen, known historically by the name Emperor Xingzong of Liao, became the Emperor of the Liao Dynasty at the age of fifteen, and his reign immediately became plagued with courtly infighting. Emperor Xingzong's mother was a low-ranking consort, Nuou Jin, but he was raised by Emperor Shengzong's wife, Empress Ji Dian. Nuou Jin quickly moved to marginalize Ji Dian and her supporters, fabricating a coup and using it to justify exiling Ji Dian and executing most of her supporters in several months of purges. Nuou Jin eventually sent assassins to kill Ji Dian; however, Ji Dian instead committed suicide.[46]

With her rival for power dead, Nuou Jin declared herself the regent and began personally conducting duties normally within the purview of the emperor. When it became clear that Emperor Xingzong was unhappy with his mother's grab for power, Nuou Jin plotted to replace the emperor with another of her sons, Zhong Yuan, whom Nuou Jin raised herself. Zhong Yuan informed the emperor of their mother's plans, however, and the emperor promptly exiled Nuou Jin.[47]

For the remainder of his reign, Emperor Xingzong would have to compete for power with his mother, whose supporters still held key postings, and whose influence was so great that she was eventually allowed to return to the capital and undergo a ceremony to symbolically de-exile herself. Zhong Yuan, for his part, would be rewarded for revealing his mother's plot by being given a succession of higher- and higher-ranking positions, culminating with a governorship outside of the capital.[47] Historian Frederick W. Mote explains the importance of this factional infighting and its relation to the Liao Dynasty's downfall by stating that it "shows to what extent the succession issue within the imperial clan still was the source of weakness in the leadership of the state. It wasted people, diverted energies, and deflected the attention of the rulers from the tasks of governing."[48]

Emperor Xingzong died in 1055. His eldest son, Yelü Hongji (who would later be known by the name Emperor Daozong of Liao), assumed the throne having already gained experience in governing while his father was alive. Unlike his father, Emperor Daozong did not face a succession crisis. While both Ji Dian and Zhong Yuan remained alive, and both had the political influence to interfere with the succession process, neither did.[49]

While Emperor Daozong's reign started off strong, it too was eventually plagued by factional infighting, aggravated by the emperor's own general weakness.[48] The emperor's first major error was in ordering the execution of Xiao A La, a loyal minister and close friend of the emperor, whom the emperor was nonetheless convinced to execute by a rival minister. The fourteenth-century History of Liao speculates that had Xiao A La not been killed, two major incidents that came to dominate Emperor Daozong's reign would have been avoided.[50] The first of these incidents was a rebellion that took place in 1063. That year, several high-ranking members of the Yelü clan, led by a grandson of Emperor Shengzong, attempted to assassinate Emperor Daozong while he was on a hunting trip. He was saved with the assistance of troops led by his mother, Empress Dowager Ren Yi, and retaliated by executing all of the people involved in the plot, as well as their immediate families.[51]

This major change in leadership solidified the power of the chancellor Yelü Yixin and his ally Yelü Renxian, a chancellor and military leader. When Yelü Renxian died in 1072, Yelü Yixin began to view Emperor Daozong's son and heir apparent, Prince Jun, as the only possible threat to Yelü Yixin's power, and set in motion plans to eliminate the prince. He first eliminated Prince Jun's mother, the emperor's wife, by fabricating evidence that the emperor's wife had an affair with a palace musician. Believing Yelü Yixin's trap, Emperor Daozong ordered his wife to commit suicide. Yelü Yixin then fabricated a coup by implicating his own enemies within the court of planning a coup that aimed to depose of Emperor Daozong and place Prince Jun on the throne. While the emperor was initially unconvinced, Yelü Yixin eventually succeeded in convincing the emperor to exile his son by creating a false confession. Prince Jun was immediately exiled, at which point Yelü Yixin sent assassins to eliminate the prince and his wife, preventing both the prince from being returned to power and Yelü Yixin's plot from being discovered.[51] Yelü Yixin's treachery was eventually discovered when, in 1079, Yelü Yixin attempted to convince the emperor to leave the new heir at the palace during a hunting trip. When other members of the court protested that the young boy would be in mortal peril if left behind with Yelü Yixin, the emperor finally saw through Yelü Yixin. By 1080 Yelü Yixin was stripped of his rank and sent to a low-ranking post outside of the capital. Shortly afterwards he was executed.[52]

Aside from the machinations of Yelü Yixin, the only other event of note from Emperor Daozong's rule was a war, which was fought between 1092 and 1102, between the Liao and a Mongolian, possibly Tatar, group known as the Zubu. The Zubu were located at the northwest border of Liao territory, and had fought several wars with the Liao when the Liao tried to expand in that direction. In 1092 the Liao attacked several other tribes in the northwest, and by 1093 the Zubu attacked the Liao, striking deep into Khitan territory. It took until 1100 for the Liao to capture and kill the Zubu chieftain, and another two years to fight of the remaining Zubu forces. The war against the Zubu was the last successful military campaign waged by the Liao Dynasty.[53]

Rise of the Jin and fall of the Liao

The 12th century saw the rapid rise of the Jurchen people, which culminated in 1115 with the foundation of the Jin Dynasty by the Jurchen warlord Aguda.[54] The Jurchens, led by Aguda, captured the Liao Dynasty's supreme capital in 1120 and its central capital in 1122. The Liao emperor Tianzuo fled the southern capital Nanjing (today's Beijing) to the western region, and his uncle Prince Yelü Chun then formed the short-lived Northern Liao in the southern capital, but died soon afterwards.[55] In 1125, the Jurchens captured Emperor Tianzuo and ended the Khitan Empire.[56]

In 1124, just before the final conquest of the Liao Dynasty, a group of Khitans led by Yelü Dashi fled northwest to the border area and military garrison of Kedun (Zhenzhou), in modern-day northern Mongolia.[57] Yelü Dashi convinced the people there, around 20,000 Liao cavalry and their families, to follow him and attempt to restore the Liao Dynasty. Yelü Dashi proclaimed himself emperor in 1131, after which he moved further west into modern Kazakhstan and then occupied the Karakhanid city of Balasaghun (in modern Kyrgyzstan). After a failed attempt in 1134 to reclaim the territory formerly held by the Liao, Dashi decided instead to stay where he was and establish a permanent Khitan state in Central Asia. The state, known as the Kara-Khitan Khanate or the Western Liao Dynasty, controlled several key trading cities, was multicultural, and showed evidence of religious tolerance. The state survived for nearly a century before being conquered by the Mongol Empire in 1218.[58]

An analysis by F. W. Mote concluded that at the time of the Liao Dynasty's fall, "the Liao state remained strong, capable of functioning at reasonable levels and possessing greater resources of war than any of its enemies" and that "one cannot find signs of serious economic or fiscal breakdown that might have impoverished or crippled its ability to respond".[59] Mote also concluded that acculturation did not lead to the replacement of traditional Khitan values with Chinese culture, and that the Khitan commoners were "supremely able and willing to fight", which Mote pointed to as evidence that Khitan society remained strong.[60] Mote instead attributes the fall of the Liao to the leadership ability of Aguda and to the actions of the Khitan Yelü and Xiao clans, which used early defeats at the hand of Aguda as a pretext for plotting the overthrow of Emperor Tianzou.[61] Historian Jacques Gernet disagrees with Mote, writing that "by the middle of the eleventh century the Khitan had lost their combative spirit and adopted a defensive attitude to their neighbors, building walls, ramparts for their towns, and fortified posts."[62] Gernet attributes this change to the influence of Buddhism, which abhors violence, as well as to Chinese wealth and culture in general. Like Mote, Gernet attributes the ultimate downfall of the Liao to the interference by the ruling clans, and he additionally credits a series of droughts and floods, as well as attacks by the Jurchen tribes on the north-east edge of Liao territory, with weakening the Liao to a critical level.[62]

Government

At its height, the Liao Dynasty controlled what is now Shanxi, Hebei, Liaoning, Jilin, Heilongjiang, and Inner Mongolia provinces in China, as well as portions of the Korean peninsula, portions of the Russian Far East, and much of the country of Mongolia.[63][64] The peak population is estimated at 750,000 Khitans and two to three million ethnic Chinese.[65]

Law and administration

The Liao Dynasty employed two separate governments operating in parallel with one another: a Northern Administration in charge of Khitan and other nomadic peoples, most of whom lived in the northern side of Liao territory, and a Southern Administration in charge of the Chinese populace that lived predominantly in the southern side. When Abaoji first established the system, these two governments did not have strict territorial boundaries, but Emperor Shizong established formally delineated boundaries for the two administrations early in his reign. The newly delineated Northern Administration had large Chinese, Bohai, and Uighur populations, and was given its own set of parallel northern and southern governments.[66]

The governments of the Northern Administration and the Southern Administration operated very differently. The Northern Administration operated under a system which Twitchett and Tietze called "essentially a great tribal leader's personal retinue".[67] Many of the governmental appointments dealt with tribal affairs, herds, and retainers serving the imperial house, and most powerful and high-ranking positions dealt with military affairs. The overwhelming majority of officeholders were Khitans, mainly from the imperial Yelü clan and the Xiao consort clan.[68] The Southern Administration was more heavily structured, with Twitchett and Tietze calling it "designed in imitation of a T'ang model".[67] Unlike the Northern Administration, many of the low- and medium-ranked officials in the Southern Administration were Chinese.[69]

The Liao Dynasty was further divided into five "circuits", each with a capital city. The general idea for this system was taken from the Bohai, although no captured Bohai cities were made into circuit capitals.[70] The five capital cities were Shangjing (上京), meaning Supreme Capital, which is located in modern-day Inner Mongolia; Nanjing (南京), meaning Southern Capital, which is located near modern-day Beijing; Dongjing (东京), meaning Eastern Capital, which is located near modern-day Liaoning; Zhongjing (中京), meaning Central Capital, which is located in modern-day Hebei province near the Laoha river; and Xijing (西京), meaning Western Capital, which is located near modern-day Datong.[71] Each circuit was headed by a powerful viceroy who had the autonomy to tailor policies to meet the needs of the population within his circuit.[69] Circuits were further subdivided into administrations called fu (府), which were metropolitan areas surrounding capital cities, and outside of metropolitan areas were divided into prefectures called zhou (州), which themselves were divided into counties called xian (县).[72]

Despite these administrative systems, important state decisions were still made by the emperor. The emperor met with officials from the Northern and Southern Administrations twice a year, but aside from that the emperor spent much of his time attending to tribal affairs outside of the capital cities.[73]

Society and culture

Spoken and written languages

The Khitan spoken language is most closely related to the Mongolic language family; some broader definitions of the Mongolic family include Khitan as a member. More broadly, Khitan is an Altaic language, although scholars are divided on the question whether the Altaic is a true language family or linguistic area in which originally distinct languages have influenced each other over a long period. Khitan shares some terms with the Altaic but non-Mongolic Turkic spoken by the Uighur peoples, who shared the steppes of North Asia with the Khitans for several hundred years.[74]

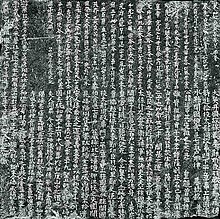

Prior to their conquest of north China and the establishment of the Liao Dynasty, the Khitans had no written language. In 920 the first of two Khitan scripts, the Khitan large script, was developed. A second script, the Khitan small script, was developed in 925.[75] Both scripts are based on the same spoken language, and both contain a mix of logographs and phonographs.[76] Despite the similarities to Chinese characters, the Khitan scripts were functionally different from Chinese.[75]

Few documents written in either the Khitan large or small script survive to this day. Most surviving specimens of both Khitan scripts are epitaph inscriptions on stone tablets, as well as a number of inscriptions on coins, mirrors and seals. Only a single manuscript text in the Khitan large script is known (Nova N 176), and no manuscripts in the Khitan small script are known.[77] The Liao emperors could read Chinese, and while there were some Chinese works translated into Khitan during the Liao Dynasty, the Confucian classics, which served as the core guide to the administration of government in China, are not known to have been translated into Khitan.[78]

Status of women

The status of women in the Liao Dynasty varied greatly, with the Khitan Liao having much a more egalitarian view towards women than the Han Chinese did. Han Chinese living under the Liao Dynasty were not forced to adopt Khitan practices, and while some Han Chinese did, many did not.[79]

Unlike Han society, which had a strict separation of responsibilities along gender lines, and placed women in a very subservient role to men, the Khitan women of the Liao Dynasty performed many of the same functions that the Khitan men did.[80] Khitan women were taught how to hunt, and managed family herds, flocks, finances, and property when their husbands were at war.[80][81][82] Upper-class women were able to hold governmental and military posts.[82]

The sexual freedoms of Liao also stood in stark contrast from those of the Han Chinese. Women from the upper Liao classes, like those of the Han Chinese upper classes, had arranged marriages, in some cases for political purposes.[83][84] However women from the lower classes of the Liao did not have arranged marriages, and would attract suitors by singing and dancing in the streets. The songs served as self-advertisements, with the women telling of their beauty, familial status, and domestic skills. Virginity was not a requirement for marriage among the Liao, and many Liao women were sexually promiscuous before marriage, which stood in sharp contrast from the beliefs of the Han Chinese.[83] Khitan women had the right to divorce their husbands and were able to remarry after being divorced.[82]

Abduction of marriage-age women was common during the Liao Dynasty. Khitans men of all social classes participated in the activity, and the abductees were both Khitan and Han. In some cases, this was a step in the courtship process, where the woman would agree to the abduction and the resulting sexual intercourse, and then the abductor and abductee would return to the woman's home to announce their intention to marry. This process was known as baimen (拜門). In other cases, the abduction would be non-consensual and would result in a rape.[85]

Marriage practices

In Liao custom betrothal was seen as being equally serious to, if not more serious than, marriage itself, and was difficult to annul. The groom would pledge to work for three years for the bride's family, pay a bride price, and lavish the bride's family with gifts. After the three years, the groom would be allowed to take the bride back to his home, and the bride would usually cut off all ties with her family.[86]

Khitan marriage practices differed from those of the Han Chinese in several ways. Men from the elite classes tended to marry women from the generation their senior. While this did not necessarily mean that there would be a large gap in ages between husband and wife, it was often the case. Among the ruling Yelü clan, the average age that boys married was sixteen, while the average age that girls married was between sixteen and twenty-two. Although rare, ages as young as twelve were recorded, for both boys and girls.[87] A special variety of polygamy known as sororate, in which a man would marry two or more women who were sisters, was practiced among the Liao elite.[82][88] Polygamy was not restricted only to sororate, with some men having three or more wives, only some of whom were sisters. Sororate continued throughout the length of the Liao Dynasty, despite laws banning the practice.[88] Over the course of the dynasty, the Liao elite moved away from polygamy and towards the Han Chinese system of having one wife and one or more concubines.[88] This was done largely to smooth over the process of inheritance.[82]

Religion

By the time Abaoji assumed control over the Khitans in the early tenth century, a majority of the Khitan population had adopted Buddhism.[89] Buddhism was practiced throughout the length of the Liao Dynasty. Monasteries were constructed during the reign of the first emperor, Taizu, and Buddhism was especially prominent during the reigns of Emperors Shengzong, Xingzong, and Daozong.[90]

Buddhist scholars living during the time of the Liao Dynasty predicted that the mofa (末法), an age in which the three treasures of Buddhism would be destroyed, was to begin in the year 1052. Previous dynasties, including the Sui and Tang, were also concerned with the mofa, although their predictions for when the mofa would start were different from the one selected by the Liao. As early as the Sui Dynasty, efforts were made to preserve Buddhist teachings by carving them into stone or burying them. These efforts continued into the Liao Dynasty, with Emperor Xingzong funding several projects in the years immediately preceeding 1052.[91]

Evidence from excavated Liao burial sites indicates that animistic or shamanistic practices were fused with Buddhism and other practices in marriage and burial ceremonies. Both animal and human sacrifices have been found in Liao tombs, alongside indications of Buddhist practice. Indications of Daoist, zodiac, and Zoroastrian influences have also been found in Liao burial sites.[92]

Cultural legacy

The influence of the Liao Dynasty on subsequent culture includes a large legacy of statuary art works, with important surviving examples in painted wood, metal, and three-color glazed sancai ceramics. The music and songs of the Liao dynasty are also known to have indirectly or directly influenced Mongol, Jurchen, and Chinese musical traditions.

The rhythmic and tonal pattern of the ci (词) form of poetry, an important part of Song Dynasty poetry, uses a set of poetic meters and is based upon certain definitive musical song tunes. The specific origin of these various original tunes and musical modes is not known, but the influence of Liao Dynasty lyrics both directly and indirectly through the music and lyrics of the Jurchen Jin Dynasty appears likely. At least one Han Chinese source considered the Liao (and Jurchen) music to be the vigorous and powerful music of horse-mounted warriors, diffused through border warfare.[93][94]

Another influence of the Liao cultural tradition is seen in the Yuan Dynasty's zaju (杂剧) theater, its associated orchestration, and the qu (曲) and sanqu (散曲) forms of Classical Chinese poetry. One documented way in which this influence occurred was through the incorporation of Khitan officers and men into the service of the Mongol forces during the first Mongol invasion of 1211 to 1215.[95] This northern route of cultural transmission of the legacy of Liao culture was then returned to China during the Yuan Dynasty.

Notes

- ^ Turchin, Adams, and Hall (2006), 222.

- ^ Template:Language icon 愛新覚羅烏拉熙春 (Aisin-Gioro Ulhicun). "遼朝國號非「哈喇契丹(遼契丹)」考:兼擬契丹大字及契丹小字的音値 (The State Name of the Liao Dynasty was not "Qara Khitai (Liao Khitai )": with Presumptions of Phonetic Values of Khitai Large Script and Khitai Small Script )" (PDF). Retrieved February 4, 2012.

{{cite web}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|1=(help) - ^ Template:Language icon 愛新覚羅烏拉熙春 (Aisin-Gioro Ulhicun). "契丹文dan gur與「東丹國」國號:兼評劉浦江「再談"東丹國"國号問題」 (Original Meaning of Dan gur in the Khitai Scripts: with a Discussion of the State Name of the Dongdanguo)" (PDF). Retrieved February 4, 2012.

- ^ Twitchett and Tietze (1994), 44-45.

- ^ a b c d Twitchett and Tietze (1994), 44.

- ^ Xu (2005), 6.

- ^ Xu (2005), 85-87.

- ^ Twitchett and Tietze (1994), 45-47.

- ^ Twitchett and Tietze (1994), 47-48.

- ^ Twitchett and Tietze (1994), 48-49.

- ^ Twitchett and Tietze (1994), 50-53.

- ^ a b Mote (1999), 37-39

- ^ Mote (1999), 39.

- ^ Wittfogel and Feng (1946), 398-399.

- ^ Wittfogel and Feng (1946), 398.

- ^ Wittfogel and Feng (1946), 400-402.

- ^ Mote (1999), 41. and Wittfogel and Feng (1946), 401.

- ^ Mote (1999), 47-49.

- ^ Shen (2001), 264.

- ^ Twitchett and Tietze (1994), 68. and Mote (1999), 49.

- ^ a b c Mote (1999), 51.

- ^ Mote (1999), 49-50.

- ^ a b Twitchett and Tietze (1994), 68.

- ^ Mote (1999), 49-51.

- ^ a b Mote (1999), 52.

- ^ Twitchett and Tietze (1994), 68-69. and Mote (1999), 50-51.

- ^ a b Twitchett and Tietze (1994), 69.

- ^ a b Twitchett and Tietze (1994), 69-70.

- ^ Smith (2006), 377. and Twitchett and Tietze (1994), 69-70.

- ^ Mote (1999), 65.

- ^ a b Twitchett and Tietze (1994), 72-74.

- ^ Twitchett and Tietze (1994), 73. and Mote (1999), 40.

- ^ Twitchett and Tietze (1994), 75. and Mote (1999), 52.

- ^ Twitchett and Tietze (1994), 76-79. and Mote (1999), 52.

- ^ Gernet (2008), 302.

- ^ Mote (1999), 199.

- ^ Twitchett and Tietze (1994), 102.

- ^ Twitchett and Tietze (1994), 103.

- ^ Twitchett and Tietze (1994), 103-104.

- ^ Twitchett and Tietze (1994), 111-112.

- ^ Mote (1999), 13-14 and 67-68.

- ^ a b c Mote (1999), 69.

- ^ Mote (1999), 69-71.

- ^ Smith (2006), 377.

- ^ Steinhardt (1997), 20.

- ^ Twitchett and Tietze (1994), 114.

- ^ a b Twitchett and Tietze (1994), 114-116.

- ^ a b Mote (1999), 200.

- ^ Twitchett and Tietze (1994), 124-125.

- ^ Twitchett and Tietze (1994), 125.

- ^ a b Twitchett and Tietze (1994), 128-134.

- ^ Twitchett and Tietze (1994), 135.

- ^ Twitchett and Tietze (1994), 138-139.

- ^ Gernet (2008), 356.

- ^ Biran (2005), 20

- ^ Biran (2005), 29-30

- ^ Biran (2005), 25-27

- ^ Gernet (2008), 354. and Mote (1999), 205-206.

- ^ Mote (1999), 204.

- ^ Mote (1999), 203.

- ^ Mote (1999), 201.

- ^ a b Gernet (2008), 354.

- ^ Steinhardt (1994), 5.

- ^ Mote (1999), 58.

- ^ Ebrey (1996), 166.

- ^ Twitchett and Tietze (1994), 77.

- ^ a b Twitchett and Tietze (1994), 78.

- ^ Twitchett and Tietze (1994), 77-78.

- ^ a b Twitchett and Tietze (1994), 79.

- ^ Wittfogel and Feng (1946), 44.

- ^ Twitchett and Tietze (1994), xxix. and Wittfogel and Feng (1946), 44.

- ^ Wittfogel and Feng (1946), 45.

- ^ Twitchett and Tietze (1994), 79-80.

- ^ Mote (1999), 34.

- ^ a b Kane (2009), 2-3.

- ^ Kane (2009), 167-168.

- ^ Template:Language icon Zaytsev, Viacheslav P. (2011). "Рукописная книга большого киданьского письма из коллекции Института восточных рукописей РАН". Письменные памятники Востока (Written Monuments of the Orient). 2 (15): 130–150. ISSN 1811-8062.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|trans_title=ignored (|trans-title=suggested) (help) - ^ Franke and Twitchett (1994), 31-36.

- ^ Johnson (2011), xvii–xviii.

- ^ a b Johnson (2011), 33–34.

- ^ Wittfogel and Feng (1946), 199.

- ^ a b c d e Mote (1999), 76.

- ^ a b Johnson (2011), 85–87.

- ^ Johnson (2011), 97.

- ^ Johnson (2011), 86–88.

- ^ Johnson (2011), 90-92.

- ^ Johnson (2011), 98.

- ^ a b c Johnson (2011), 99-100.

- ^ Mote (1999), 43.

- ^ Shen (2001), 264-265.

- ^ Shen (2001), 266-269.

- ^ Johnson (2011), 53 and 84.

- ^ Crump (1990), 25-26

- ^ Template:Language icon 中国戏曲研究院 (Chinese Academy of Opera), ed. (1959). 中国古典戏曲论著集成 (Collection of Reviews of Classical Chinese Drama). Beijing: 中国戏剧出版社 (China Drama Publishing House). p. 241.

- ^ Crump (1990), 12-13

References

- Biran, Michal (2005). The Empire of the Qara Khitai in Eurasian History: Between China and the Islamic World. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0521842263.

- Crump, James Irving (1980). Chinese Theater in the Days of Kublai Khan. Ann Arbor: Center for Chinese Studies, University of Michigan. ISBN 0-89264-093-6.

- Ebrey, Patricia Buckley (1996). The Cambridge Illustrated History of China (1st pbk. ed.). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 9780521669917.

- Franke, Herbert; Twitchett, Denis (1994). "Introduction". The Cambridge History of China, Volume 6, Alien Regime and Border States, 907-1368. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. pp. 1–42. ISBN 0521243319.

- Gernet, Jacques (2008). A History of Chinese Civilization (2nd ed.). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 9780521497817.

- Johnson, Linda Cooke (2011). Women of the Conquest Dynasties. Honolulu: University of Hawai'i Press. ISBN 9780824834043.

- Kane, Daniel (2009). The Kitan Language and Script. Leiden: Brill. ISBN 9789004168299.

- Mote, Frederick W. (1999). Imperial China: 900–1800. Cambridge: Harvard University Press. ISBN 0674445155.

- Shen, Hsueh-Man (2001). "Realizing the Buddha's "Dharma" Body during the Mofa Period: A Study of Liao Buddhist Relic Deposits". Artibus Asiae. 61 (2): 263–303. Retrieved 11 February 2012.

- Smith, Paul Jakov (2006). "Shuihu zhuan and the Military Subculture of the Northern Song, 960–1127". Harvard Journal of Asiatic Studies. 66 (2): 363–422. Retrieved 18 September 2012.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - Steinhardt, Nancy Shatzman (1994). "Liao: An Architectural Tradition in the Making". Artibus Asiae. 1/2. 54: 5–39. Retrieved 19 February 2012.

- Steinhardt, Nancy Shatzman (1997). Liao architecture. Honolulu: University of Hawai'i Press. ISBN 9780824818432.

- Turchin, Peter (December 2006). "East-West Orientation of Historical Empires and Modern States" (PDF). Journal of World-Systems Research. 12 (2): 219–229. Retrieved 12 August 2010.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - Twitchett, Denis; Tietze, Klaus-Peter (1994). "The Liao". In Franke, Herbert; Twitchett, Denis (eds.). The Cambridge History of China, Volume 6, Alien Regime and Border States, 907-1368. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. pp. 43–153. ISBN 0521243319.

- Wittfogel, Karl A. (1946). "History of Chinese Society Liao (907-1125)". Transactions of the American Philosophical Society. 36: 1–752. Retrieved 10 February 2012.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - Xu, Elina-Qian (2005). Historical development of the pre-dynastic Khitan. Helsinki: University of Helsinki. ISBN 9521004983.

External links

- "Gilded Splendor" - Liao Dynasty art at Asiasociety.org

- Lecture on the Liao by Valerie Hansen (lecture begins at 4:40)