Nicolae Constantin Batzaria

Nicolae Constantin Batzaria | |

|---|---|

Batzaria in 1940 | |

| Born | November 20, 1874 Kruševo, Manastir vilayet, Ottoman Empire |

| Died | January 28, 1952 (aged 77) Bucharest (Ghencea), Communist Romania |

| Pen name | Ali Baba, N. Macedoneanu, Moș Ene, Moș Nae, Dinu Pivniceru |

| Occupation | Short story writer, novelist, schoolteacher, folklorist, poet, journalist, politician |

| Nationality | Ottoman (to 1915) Romanian (1915–1952) |

| Period | 1901–1944 |

| Genre | Anecdote, children's literature, children's rhyme, comic strip, essay, fairy tale, fantasy, genre fiction, memoir, novella, satire, travel literature |

| Signature | |

Nicolae Constantin Batzaria (Romanian pronunciation: [nikoˈla.e konstanˈtim batsaˈri.a]; Greek: Νικολάε Κονσταντίν Μπατσαρία, Turkish: Nikola Konstantin Basarya; last name also Besaria, Bațaria or Bazaria; also known under the pen names Moș Nae, Moș Ene and Ali Baba; November 20, 1874 – January 28, 1952), was an Aromanian cultural activist, Ottoman statesman and Romanian writer. A schoolteacher and inspector of Aromanian education within Ottoman lands, he stood for the intellectual and political current, espoused by the Macedo-Romanian Cultural Society, which closely identified with both Romanian nationalism and Ottomanism. Batzaria was trained at the University of Bucharest, where he became a disciple of historian Nicolae Iorga, and established his reputation as a journalist before 1908—the string of publications he founded, sometimes with financial support from the Kingdom of Romania, includes Românul de la Pind and Lumina. During his thirties, he joined the clandestine revolutionary movement known as the Young Turks, serving as its liaison with Aromanian factions in Macedonia and Rumelia. He was briefly imprisoned for such activities, but the victorious Young Turk Revolution in 1908 brought him to the forefront of Ottoman politics.

A member of the Ottoman Senate in 1908–1915, Batzaria was also Minister of Public Works under the Three Pashas. He was tasked with several diplomatic missions, including attending the London Conference of 1913, and sought to preserve the purpose of Ottomanism by seeking tactical alliances against, and finally with, the Kingdom of Bulgaria. Alerted by the Pashas' World War I alliances and their reliance on an exclusivist Turkish nationalism, he soon after quit the Ottoman political scene and left into voluntary exile. Naturalized a Romanian in early 1915, he debuted in local politics as a Nationalist-Conservative, switching his allegiance toward the Entente Powers—favoring war against Bulgaria and the Ottomans alike. The fulfillment of Greater Romania in the interwar era saw him affiliating with a number of political movements, from the People's Party to the National Peasants' Party, before he finally settled for the National Liberals in the early 1930s. A member of the Romanian Senate and Assembly of Deputies, each for one term, he was also Prefect of Timiș-Torontal in April–May 1931.

In tandem with his political involvement, Batzaria became a prolific contributor to Romanian literature, producing works of genre fiction and children's literature. Together with comic strip artist Marin Iorda, he created Haplea, one of the most popular characters in early Romanian comics. Batzaria also collected and retold fairy tales from various folkloric traditions, while publishing original novels for adolescents and memoirs of his life in Macedonia. Batzaria's scholarship and activism seeped into affection for minority groups, including the Gagauz, the Romani people, the Armenians, and, initially, the Jews. He was active on the staff of Romania's leading leftist journals, Adevărul and Dimineața, as well as founder of the latter's supplement for children, before switching his allegiance to the right-wing Universul. His turn toward the latter was signaled by the Romanian far-right as the adoption of antisemitism, and, by 1937, he had become explicit in his sympathy for the fascist Iron Guard; during World War II, he supported the Ion Antonescu regime, and was enthusiastically anti-Soviet in his articles and children's prose. Batzaria was banned, persecuted, and finally imprisoned by the postwar communist regime. He spent his final years in obscure captivity, dying of spinal cancer.

Biography

[edit]Early life and activities

[edit]Batzaria was a native of Kruševo (Crushuva), a village in Ottoman-ruled Manastir vilayet, presently in North Macedonia. His Aromanian family had numerous branches outside that region: migrant members had settled in the Kingdom of Romania, in Anatolia, and in the Khedivate of Egypt.[1] Nicolae's father had stayed in Kruševo, but by 1873 had joined in the effort, led by Steriu N. Cionescu, to set up some of the first Romanian-sponsored schools for the Aromanians.[2] The future politician and author was raised in the Eastern Orthodox Church, and later affiliated with its Romanian branch, being an occasional contributor to its program of catechesis;[3] he grew up in Kruševo, where he studied under renowned Aromanian teacher Sterie Cosmescu.[1] He attended the Romanian High School of Bitola, where he learned French with the Lazarist Jean-Claude Faveyrial—who also introduced him to theater, by making him appear in an amateur play.[4] During a summer vacation in Kruševo, he attempted to stage his own version of a play by Vasile Alecsandri. As he recalled in 1932, the project ended up as a "pummeling among us thespians", prompted by the male lead's refusal to appear in travesti.[5]

Graduating in 1891,[6] Batzaria was sent to further his education in Romania, at the Faculties of Letters and Law, University of Bucharest.[7][8][9] The young man became a dedicated disciple of Romanian nationalist theorist Nicolae Iorga, who was inaugurating his lectures in history during Batzaria's first year there.[10][11] He shared Iorga's belief, consolidated with time, that the Aromanians were not an isolated Balkan ethnicity, but part of larger Romanian ethnic community. As he himself explained, "the Romanian people [is] a unitary and indivisible body, regardless of the region wherein historical circumstances have settled it", and the "Macedonian Romanians" constituted "the most aloof branch of the Romanian trunk".[12] Lacking funds for his tuition, Batzaria never graduated.[1] Instead, he earned his recognition as a journalist, educator, and analyst. A polyglot, he could speak Turkish, Greek, Bulgarian, and Serbian, in addition to French, his native Aromanian, and the Romanian language.[13] He regarded the latter two as closely related, with Aromanian as the less prestigious, subordinate dialect of a language that had originated north of the Danube.[14] In one article, he acknowledged that, without immersion, Aromanians would struggle to understand the metropolitan language, or "Daco-Romanian".[5] Literary critic and memoirist Barbu Cioculescu, who befriended Batzaria as a child, recalls that the Aromanian journalist "spoke all Balkan languages", and "perfect Romanian" with a "brittle" accent.[15]

While in Romania, Batzaria also began his collaboration with Romanian journals: Adevărul, Dimineața, Flacăra, Arhiva, Ovidiu and Gândul Nostru.[8][16] Also notable is his work with magazines published by the Aromanian diaspora. These publications depicted the Aromanians as a subgroup of the Romanian people.[17] They include Peninsula Balcanică ("The Balkan Peninsula", the self-styled "Organ for the Romanian interests in the Orient"), Macedonia and Frățilia ("Brotherhood").[17] The latter, published from both Bitola and Bucharest, and then from the Macedonian metropolis of Thessaloniki, had Nicolae Papahagi and Nuși Tulliu on its editorial board.[18] Batzaria made his editorial debut with a volume of anecdotes, Părăvulii—the title, which has to be translated for speakers of Romanian, approximates to "Parables" or "Comparisons".[19] Printed in Bucharest in 1901,[8] it was in fact self-published by Batzaria and Papahagi's own imprint, called Biblioteca Populară Aromânească ("Aromanian People's Library").[5] The volume reportedly made him an instant celebrity in Aromanian circles.[20]

Batzaria returned to Macedonia as a schoolteacher, educating children at the Ioannina school (January–June 1894), and subsequently at his alma mater in Bitola; he was also employed by the school of Gopeš, between September 1903 and January 1904.[21] Around that time, he reportedly met the younger Mustafa Kemal (Atatürk), who was studying at Monastir Military High School.[22] In 1899, Batzaria and his colleagues notably persuaded Take Ionescu, the Romanian Education Minister, to allocate some 724,000 lei as a grant to Macedonian schools, and virulently protested when later governments halved this annual income.[23] He then became chief inspector of the Romanian educational institutions in the Ottoman provinces of Kosovo and Salonika.[9][24] Historian Gheorghe Zbuchea, who researched the self-identification of Aromanians as a Romanian subgroup, sees Batzaria as "the most important representative of the national Romanian movement" among early 20th century Ottoman residents,[25] and "without doubt one of the most complex personalities illustrating the history of trans-Danubian Romanianism".[1] Batzaria's debut in Macedonian cultural debates came at a turning point: through her political representatives, Romania was reexamining the scope of her involvement in the Macedonian question, and asserting that it held no ambition to annex Aromanian land.[26]

From Macedonia, Nicolae Batzaria became a correspondent of Neamul Românesc, a brochure and later magazine published in Romania by Iorga.[12] At that stage, Batzaria, with Tulliu, Nicolae Papahagi and Pericle Papahagi, founded the Association of Educationists in Service to the Romanian People of Turkey (that is, the Aromanians), a union of professionals based in Bitola. They were on a mission to Romania, where their demand for more funding sparked lively debates among Romanian politicians, but Education Minister Spiru Haret eventually signed off a special Macedonian fund, worth 600,000 lei (later increased to over 1 million).[27] The group was also granted a private audience with King Carol I, who showed sympathy for the Aromanian campaign and agreed to receive Batzaria on several other occasions.[23] Perceived as a figure of importance among the Aromanian delegates, Batzaria also began his collaboration with the magazine Sămănătorul, chaired at the time by Iorga.[28]

Lumina, Deșteptarea and Young Turks affiliation

[edit]Nicolae Batzaria's nationalism, aimed specifically against the Ottoman Greeks, became more evident in 1903 when he founded the Bucharest gazette Românul de la Pind ("The Romanian of the Pindus"). It was published under the motto Timeo Danaos et dona ferentes, and monitored the Greek offensive against Aromanian institutions in places such as Mulovishti, calling out for action against the "perfidious" and "inhumane" enemy.[29] In 1905, Batzaria's paper fused into Revista Macedoniei ("Macedonia Magazine"), put out by a league of exiles, the Macedo-Romanian Cultural Society (SCMR).[29] Batzaria and his colleagues in Bitola put out Lumina ("The Light"). A self-styled "popular magazine for the Romanians of the Ottoman Empire", it divided its content into a "clean" Romanian and a smaller Aromanian section, aiming to show "the kinship of these two languages", and arguing that "dialects are preserved, but not cultivated."[30] Batzaria became, in 1904, its editorial director, taking over from founder Dumitru Cosmulei.[31] Lumina was the first Aromanian magazine to be published within the lands of Rumelia (Turkey-in-Europe), and espoused a cultural agenda without political objectives, setting up the first popular library for Aromanian- and Romanian-speakers of Macedonian descent.[32] However, the Association of Educationists stated explicitly that its goal was to elevate the "national and religious sentiment" among "the Romanian people of the Ottoman Empire".[33] Lumina was noted for its better quality, receiving a 2,880 lei grant from Romania's government, but was no longer in print by late 1908.[29] Following a ban on political activities by Sultan Abdul Hamid II, Batzaria was arrested by local Ottoman officials, an experience which later served him in writing the memoir În închisorile turcești ("In Turkish Prisons").[34]

In May 1905, Abdul Hamid decided to give recognition to some Aromanian demands, principally their recognition as a distinct entity within the imperial borders.[35] On May 10 (Romania's first national holiday), Aromanian students at Thessaloniki's School of Commerce, where Batzaria was then teaching Romanian,[36] staged La Farce de maître Pathelin, adapted by him from Molière's version.[37] In October, as the Bitola school marked its silver jubilee, his poem Erà întreg ca tine ("He Was as Sound as You") was recited by local student P. Marcu.[38] By 1907, the city's Aromanians had been largely alienated by Batzaria's politics: his claim to represent the Romanian state, which allowed him executive control over the schools; opponents such as Christea Lambru fought instead for private schools. This schism resulted in the establishment of a separate Aromanian school in Thessaloniki. As claimed by Lambru, in 1908 it had "ten times as many students as the inspectorate school."[39]

Batzaria's contribution to the press was diversified in that same interval. With discreet help from Romanian officials, he and Nicolae Papahagi founded, in Thessaloniki, the French-language sheet Courrier des Balkans ("Balkan Dispatch", published from 1904).[40] It was specifically designed as a propaganda sheet for the Aromanian cause, informing its international readership about the Latin origins and Philo-Romanian agenda of Aromanian nationalism.[41] He also worked on, or helped found, other Aromanian organs in the vernacular, including Glasul Macedoniei ("The Macedonian Voice")[16] and Grai Bun ("The Good Speech"). Late in 1906, Revista Macedoniei turned back into Românul de la Pind, struggling to survive as a self-funded national tribune.[29] Batzaria also replaced N. Macedoneanu as Grai Bun editor in 1907, but the magazine was under-financed and went bankrupt the same year.[31] His Romanian articles were still published in Iorga's Neamul Românesc, but also in the rival journal Viața Romînească.[16] In 1908, Batzaria founded what is seen by some as the first ever Aromanian-language newspaper, Deșteptarea ("The Awakening"), again from Thessaloniki.[8][5][13][42] The next year, it received a sponsorship of 6,000 lei from the Romanian government, and began agitating for the introduction of Aromanian classes in Ottoman primary schools.[31] Nevertheless, Deșteptarea went out of business in 1910.[31][42]

Beginning in 1907, Batzaria took a direct interest in the development of revolutionary conspiracies which aimed to reshape the Ottoman Empire from within. Turkish poet Aka Gündüz, who spoke some Aromanian and befriended the school inspector, recalls that Batzaria was on exceptional terms with the conspiratorial leader, Mehmed Talat.[43] Having also established contacts with İsmail Enver, Batzaria thereafter affiliated with the multi-ethnic Committee of Union and Progress, a clandestine core of the Young Turks movement.[9][44] According to his own statements, he was acquainted with figures at the forefront of the Young Turks organizations: Ahmed Djemal (one of the future "Three Pashas", alongside Enver and Talat), Mehmet Cavit Bey, Hafiz Hakki and others.[45] This was partly backed by Enver's notes in his diary, which includes the mention: "I was instrumental in bringing into the Society the first Christian members. For instance Basarya effendi."[46] Batzaria himself claimed to have been initiated into the society by Djemal and following a ritual similar to that of "nihilists" in the Russian Empire: an oath on a revolver placed inside a poorly lit room, while guarded by men dressed in black and red cloth.[9] Supposedly, Batzaria also joined the Freemasonry at some point in his life.[9]

Modern Turkish historian Kemal H. Karpat connects these events with a larger Young Turks agenda of attracting Aromanians into a political alliance, in contrast to the official policies of the rival Balkan states, all of which refused to recognize the Aromanian ethnicity as distinct.[47] Zbuchea passed a similar judgment, concluding: "Balkan Romanians actively supported the actions of the Young Turks, believing that they provided good opportunities for modernization and perhaps guarantees regarding their future."[25] Another Turkish researcher, M. Şükrü Hanioğlu, looks at the alliance from the point of view of a larger dispute between Greece (and the Greeks in Ottoman lands) on one hand, and, on the other, Ottoman leaders and their Aromanian subjects. Proposing that Aromanian activists, like their Albanian counterparts, "supported the preservation of Ottoman rule in Macedonia" primarily for fear of the Greeks, Hanioğlu highlights the part played by British mediators in fostering the Ottoman–Aromanian entente.[48] He notes that, "with the exception of the Jews", Aromanians were the only non-Islamic community to be drawn into the Ottomanist projects.[49]

Ottoman senator and minister

[edit]

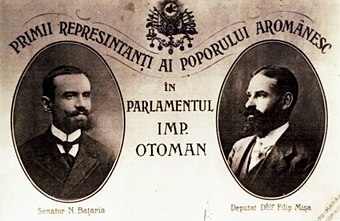

In July 1908, the Aromanian intellectual was propelled to high office by the Young Turk Revolution and the Second Constitutional Era. Days after the events, he visited Constantinople (now Istanbul) as the main delegate of an Aromanian congress from Üsküb. He was personally welcomed by Djemal, Cavit Bey, and Enver, then addressed the crowds gathering in Freedom Square; his twin speeches, in Ottoman Turkish, French and Aromanian, proclaimed an era of "freedom and safety" for all Ottoman subjects.[50] Batzaria was a candidate for the Third Chamber of Deputies; ahead of elections in December, he toured Macedonia, being welcomed by the Aromanians of Veria and Xirolivado, but also by the Megleno-Romanians—including the Muslim ones of Notia.[51] The Young Turk party ultimately rewarded his contribution, legally interpreted as "high services to the State", by assigning him a special non-elective seat in the Ottoman Senate (a status similar to that of another Aromanian Young Turk, Filip Mișea, who served in Chamber).[52] As Zbuchea notes, Batzaria was unqualified for the office, as he was neither forty years old nor a distinguished bureaucrat, and only owed his promotion to his conspiratorial background.[53] In early 1909, Nicolae Tacit was assigned to replace him as inspector.[54]

By then, Batzaria is said to have also become a personal friend of the new sultan, Mehmed V,[16] and of Education Minister Abdurrahman Şeref, who reportedly shared his reverence for Iorga.[55] A regular contributor to Le Jeune Turc and other newspapers based in Constantinople, the Aromanian campaigner was also appointed vice-president of the Turkish Red Crescent, a humanitarian society, which provided him with close insight into the social contribution of Muslim women volunteers, and, through extension, an understanding of Islamic feminism.[56] The next few years were a period of maximal autonomy for Mehmed's Aromanian subjects, who could elect their own local government, eagerly learned Turkish, and, still committed to Ottomanism, were promoted within the bureaucratic corps.[57]

Commenting on what he called the "noble toleration" of Aromanians by Turks, Batzaria recalled in 1943 that: "In Turkey's Romanian schools, classes were held which used the same textbooks as classes held in Romania."[58] In mid 1911, he was also advocating for the Albanians, advising Grand Vizier Ibrahim Hakki Pasha to unite the Albanian political and religious faction under the "single force of Ottomanism".[59] Alongside Ali Galib Bey, Ismail Hakkı Efendi, Mehmed Said Pasha, Salih Hulusi Pasha and others, he served on the Senate committee which dissolved the Chamber, in preparation for the election of 1912.[60] His own community was still dissatisfied with various issues, most of with all its automatic religious inclusion in the Rum Millet, dominated by ethnic Greeks. Batzaria was personally becoming involved in a dispute with the Ecumenical Patriarchate of Constantinople, campaigning among the Turks for the recognition of a separate Aromanian bishopric.[61] The failure of this project, like the under-representation of Aromanians in the Senate, caused some of Batzaria's fellow activists to feel disgruntled.[62]

On September 22, 1912, as the Ottoman Empire was entering the First Balkan War, Batzaria spoke in front of 15,000 people at The Hippodrome, noting that non-Muslims did not wish to be liberated by the anti-Ottoman coalition: "We are free, and only demand our Ottoman freedom."[63] He was then secretly dispatched to Bucharest: Gabriel Noradunkyan, as the Ottoman Foreign Minister, asked him to talk the Romanians into staging military maneuvers on the border with the Kingdom of Bulgaria, as a means to draw Bulgarian troops away from the Ottoman front. As revealed by Batzaria, this request was swiftly denied by the Prime Minister of Romania, Titu Maiorescu. He had more support from the opposition National Liberal Party (PNL), meeting and befriending its leader, Ion I. C. Brătianu.[64] The partition of Macedonia, which resulted from the Ottoman defeat, put a stop to Românul de la Pind, which closed down at the same time as other Aromanian nationalist papers.[65] However, Batzaria's political career was advanced further by Enver's military coup in January 1913: he became Minister of Public Works in Enver's cabinet, without interrupting his journalistic activities.[9][66] On April 28, 1913, he received the Order of the Medjidie, 1st Class.[67] It was also he who represented the executive at the London Conference, where he acknowledged Ottoman losses.[9][68][69]

Against the law which specified that members of the Ottoman executive could not serve in the Senate, Batzaria did not lose his seat.[70] As was later revealed, he continued to act as a partisan of Romanian policies and sent secret reports to his friend, King Carol I of Romania.[23] His networking took him into the Romanian communities of Austria-Hungary, and more specifically Transylvania: late 1913 saw him visiting Brassó (Brașov). Horia Petra-Petrescu, who met him in these circumstances, recalls taking him to the Romanian Gymnasium (which had been founded by the Aromanian Andrei Șaguna, whom Batzaria appeared to hold in high esteem).[71] In early 1914, Le Jeune Turc published Batzaria's praise for Iorga and the Bucharest Institute of South-East European Studies.[72] As Ottoman administrators were being expelled from the Balkans, he and his fellow Aromanian intellectuals tended to support the doomed project of an independent, multi-ethnic, Macedonia.[73] In the short peaceful hiatus which followed his return from London, Batzaria represented the empire in secret talks with Maiorescu, negotiating a new alliance—against Bulgaria.[74] As he himself recalled, the request was refused by Romanian politicians, who stated that they wished to avoid attacking other Christian nations.[75] The Ottoman approach, however, resonated with Romania's intentions, and both states eventually defeated Bulgaria in the Second Balkan War.[76]

Relocation to Romania

[edit]In May 1914, Batzaria accompanied Talat, who was visiting Bucharest in his capacity as Ottoman Minister of the Interior;[77] both men now shared the goal of forging a Bulgarian–Ottoman–Romanian alliance.[78] Shortly after, the July Crisis resulted in the outbreak of World War I. The Ottoman realm, Austria-Hungary, and Bulgaria were aligned with the German Empire and to the other Central Powers, while Romania maintained neutrality. On August 3, Iorga, who supported the Entente Powers, chided his former pupil for his "detestable ideas". As paraphrased by Iorga, Batzaria had voiced his endorsement of Bulgarian irredentism, suggesting that Romania could only benefit from giving her endorsement to a "new Balkan imperialism".[79] Batzaria also welcomed Austrian participation in the war "for the cause of civilization", adding that all subject peoples of the Habsburg Monarchy would eventually understand that "their fate depends on that of the Monarchy."[80]

The following months brought a clash of interests between Batzaria and all Three Pashas. Already alarmed by the officialized Turkification process,[9][25][81] the Aromanian intellectual emerged as an opponent of the Central Powers. On January 16, 1915, he and the Macedonian Bulgarian Stojan Tilkoff jointly gave up their seats in the Ottoman Senate.[82] As reported in the Pester Lloyd, "these resignations had become necessary as a result of Turkey's new territorial structure, which no longer had [...] Vlach or Bulgarian constituencies."[83] Batzaria then traveled to Bucharest, where he acknowledged that the "Romanians of Turkey" were no longer in Ottoman-controlled territory, but also that he could not bear the thought of Romania going to war against the Ottomans. He announced plans on settling there, and that he would apply for naturalization as a Romanian.[84] Batzaria was by then a correspondent for Iorga's new magazine, Ramuri.[12]

The former minister obtained his new citizenship by special vote of the Senate of Romania, on January 28, 1915.[85] Shortly after, he became a militant in Nicolae Filipescu's Nationalist-Conservatives, who advocated for joining the Entente. Opinia newspaper commented on this "conundrum" (bucluc), noting that Batzaria, "hitherto a Turk", was now being recruited by a Russophile lobby.[86] In mid-1916, Batzaria and other SCMR figures, including Vasile Ceanescu, became involved in monitoring Aromanian colonies in Romania, specifically those who had been mass-relocated in Southern Dobruja. They censured the local authorities in Caliacra County for having "unleashed a targeted persecution of the Macedonian Romanians".[87] After August 1916, when Romania declared war on the Central Powers, he opted for settling in neutral Switzerland.[9][88]

He eventually moved back to Bucharest upon the war's end— which saw the consolidation of a Greater Romania, including Transylvania, the Banat, Bukovina, and Bessarabia. Inhabiting a townhouse at 10 Doctor Radovici Street in Cotroceni,[89] he embarked on a career in writing, publishing a succession of fiction and nonfiction volumes in Romanian. He was, in January 1919, a co-founder of the Greater Romanian Journalists' trade union (Union of Professional Journalists),[90] and, in 1921, published his În închisorile turcești with Editura Alcaly.[91] He later produced a series of books detailing the lives of women in the Ottoman Empire and the modern Turkish state: Spovedanii de cadâne. Nuvele din viața turcească ("Confessions of Turkish Odalisques. Novellas from Turkish Life", 1921), Turcoaicele ("The Turkish Women", 1921), Sărmana Lila. Roman din viața cadânelor ("Poor Leila. A Novel from the Life of Odalisques", 1922), Prima turcoaică ("The First of Turkish Women", n.d.), as well as several translations of foreign books on this subject.[92] One of his stories about Ottoman womanhood, Vecina dela San-Stefano ("The Neighbor of Yeşilköy"), was published by the literary review Gândirea in its June 1922 issue.[93] Around the same time, the Viața Romînească publishers issued his booklet România văzută de departe ("Romania Seen from a Distance"), a book of essays which sought to revive confidence and self-respect among Romanian citizens.[94]

Batzaria was welcomed into the League for the Cultural Unity of All Romanians (LUCTR), chaired by Iorga, and, in mid-1923, was tasked with organizing its summer school in Vălenii de Munte.[89] Additionally a member of the People's Party, he served a term in the Senate of Greater Romania (coinciding with Alexandru Averescu's term as Prime Minister).[9][95] By 1926, he had rallied with the opposition Romanian National Party (PNR). Included in its Permanent Delegation together with Iorga, he approved of PNR's fusion with the Romanian Peasantists, affiliating with the resulting National Peasants' Party (PNȚ).[96] During the interwar, he also became a regular contributor to the country's main left-wing dailies: Adevărul and Dimineața. The journals' owners assigned Batzaria with the task of managing and editing a junior version of Dimineața, Dimineața Copiilor ("The Children's Morning"). Story goes that he was not just managing the supplement, but in effect writing down most content for each issue.[97]

While at Adevărul, Batzaria stood accused by right-wing competitors of excessively promoting the National Peasantist leader Iuliu Maniu in view of the 1926 election. A nationalist newspaper, Țara Noastră, argued that Batzaria's political columns were effectively coaching the public to vote PNȚ, and mocked their author as "a former Young Turk and ministerial colleague of that famous [İsmail] Enver-bey".[98] Like the PNȚ, the Adevărul journalist proposed the preservation of communal and regional autonomy in Greater Romania, denouncing centralization schemes as "ferocious reactionarism".[99] A while after, Batzaria drew attention to himself for writing, in Dimineața, about the need to protect the religious and communal liberties of the Jewish minority. The National-Christian Defense League, an antisemitic political faction, reacted strongly against his arguments, accusing Batzaria of having "sold his soul" to the Jewish owners of Adevărul, and to "kike interests" in general.[100] During legislative elections in July 1927, he was allegedly "arrested and stripped" by the local authorities in Cislău.[101] The year 1928 saw Batzaria protesting against the escalation of violence against journalists. His Adevărul piece was prompted by a brawl at the offices of Curentul daily, as well as by attacks on provincial newspapers.[102]

Batzaria still maintained an interest in propagating the cause of Aromanians. The interwar years saw him joining the General Board of the SCMR, of which he was for a while President.[103] He was one of the high-level Aromanian intellectuals who issued public protests when, in 1924, the Greek Gendarmes organized a crackdown against Aromanian activism in the Pindus.[104] In 1927, Societatea de Mâine journal featured one of Batzaria's studies on the ethnic minorities of the Balkans, where he contrasted the persecution of Aromanians in the Kingdom of Yugoslavia with their "unexpected" toleration in Greece.[105] Attending a congress of the LUCTR, hosted in Cluj in June 1929, he spoke with "moving detail" about the Aromanian community as a whole.[106] Still involved with the SCMR and the Aromanian colonists, in September he gave a report about 400 families who had been assigned land in Southern Dobruja, and who were still "deprived of any means to make a living".[107]

The Haplea years

[edit]In 1928, Batzaria was a judge for a national Miss Romania beauty contest, organized by Realitatea Ilustrată magazine and journalist Alexandru Tzigara-Samurcaș (the other members of this panel being female activist Alexandrina Cantacuzino, actress Maria Giurgea, politician Alexandru Mavrodi, novelist Liviu Rebreanu and visual artists Jean Alexandru Steriadi and Friedrich Storck).[108] As an Adevărul journalist, Batzaria nevertheless warned against politically militant feminism and women's suffrage, urging women to find their comfort in marriage.[109] Speaking in 1930, he suggested that the idea of a feminist party in gender-biased Romania was absurd, arguing that women could either support their husbands' political activities or, at most, affiliate with the existing parties.[110]

Batzaria's work in children's literature, taking diverse forms, was often published under the pen names Moș Nae ("Old Man Nae", a term of respect applied to the hypocorism of Nicolae) and Ali Baba (after the eponymous character in One Thousand and One Nights).[19][111] Another variant he favored was Moș Ene,[112] alongside Dinu Pivniceru and N. Macedoneanu.[19] By 1925, Batzaria had created the satirical character Haplea (or "Gobbles"), whom he made into a protagonist for some of Romania's first comic strips.[68][113][114][115] A Christmas 1926 volume, comprising 73 Haplea stories, was welcomed at the time as one of the best books for children.[116] Other characters created by Batzaria in various literary genres include Haplina (the female version and regular companion of Haplea), Hăplișor (their child), Lir and Tibișir (known together as doi isteți nătăfleți, "two clever gawks"), and Uitucilă (from a uita, "to forget").[117] The graphics to Batzaria's rhymed captions were provided by caricaturist Marin Iorda, who also worked on a cinema version of Haplea (one of the first samples of Romanian animation).[68][115][118] It was a compendium of the Dimineața comics, with both Iorda and Batzaria (the credited screenwriter) drawn in as supporting characters.[115] Premiered in December 1927 at Cinema Trianon of Bucharest, it had been in production for almost a year.[115]

From 1929, Batzaria also took over as editor and host of the children's show Ora Copiilor, on National Radio.[119] This collaboration lasted until 1932, during which time Batzaria also gave radio conferences on Oriental subjects (historical Istanbul, the Albanian Revolt of 1912 and the Quran) or on various other topics.[119] By 1930, when he attended the First Balkan Conference as a member of its Intellectual Committee,[120] Batzaria had become known for his genre fiction novels, addressed to the general public and registering much success. Among these were Jertfa Lilianei ("Liliana's Sacrifice"), Răpirea celor două fetițe ("The Kidnapping of the Two Little Girls"),[117] Micul lustragiu ("The Little Shoeshiner") and Ina, fetița prigonită ("Ina, the Persecuted Little Girl").[121] His main fairy tale collection was published as Povești de aur ("Golden Stories").[122] Also in 1930, he worked state-approved textbooks for the 2nd, 3rd and 4th grades, co-authored with P. Puchianu and D. Stoica and published by Scrisul Românesc of Craiova.[123] Alongside Iorga, Gheorghe Balș, George Murnu, and Camil Ressu, he networked with Armenian Romanians such as H. Dj. Siruni, helping to curate the Armenian art exhibit.[124]

Politically, Batzaria had switched to the PNL, and represented its group within the General Council of Bucharest;[125] around 1930, he had entered the Citizens' Committees, a trans-political coalition established by Dem I. Dobrescu, heading their central council.[126] The new Romanian king, Carol II, appointed Iorga as prime minister in early 1931, with Iorga's Democratic Nationalists and their allies also taking up posts in the local administration. On April 25, Batzaria was made Prefect of Timiș-Torontal County, in southwestern Romania.[127] This appointment came with the phasing out of the regional governorates which had been established by the PNȚ; from April 28, Batzaria took over as the last, and temporary, governor of the Banat.[128] He only served in both capacities for less than two weeks: on May 8, Constantin Argetoianu of Internal Affairs had him replaced with Aurel Cioban.[129] Batzaria and Iorga soon quarreled: in March 1932, Neamul Românesc reported on a Bucharest PNL meeting at which Batzaria had promised to use a "fire whip" against the regime. The newspaper also scolded Batzaria for his "flimsy" claim that Iorga had "savagely mistreated" students engaged in anti-government protests.[130] Batzaria benefited from the PNL sweep of December 1933, as the eighth of 20 National Liberals who took seats in the Assembly of Deputies for Ilfov County.[131] His interventions there included an impromptu lecture about the Gagauz people in southern Bessarabia, a topic on which his colleagues in the Assembly were generally uneducated.[132] He also supported amending the nationality law to give Aromanian colonists, who had been denaturalized by their respective Balkan states, a fast-track to Romanian citizenship.[133]

In tandem, Batzaria took to the applied study of philology, which also had political and social implications, as when dealing with exonyms. A January 1931 piece discussed the annoyance felt by Aromanian settlers in Romania at being labeled "Koutsovlachs" (cuțovlahi, or "Lame Vlachs").[134] In September 1933, he commented in Adevărul about the Romani minority and its first efforts at community representation. A sympathizer of the cause, he declared himself puzzled that these organizations still used the exonym țigani ("Gypsies"); his arguments may have inspired activist Gheorghe A. Lăzăreanu-Lăzurică, who set up his own General Union of Roma in Romania.[135] Batzaria remained critical of those who claimed that a 19th-century author, Anton Pann, was of non-Romanian (and possibly Romani) origin, claiming that the coppersmiths from whom Pann descended were "nomadic Romanians."[136]

Batzaria's other work took the form of literary studies: he reportedly consulted researcher Șerban Cioculescu about the Balkan origins of classical Romanian dramatist Ion Luca Caragiale.[15] His interest in Oriental themes also touched his reviews of works by other writers, such as his 1932 essay on the Arabic and Persian motifs reused by Caragiale in the Kir Ianulea story.[137] Caragiale's acquaintance with Ottoman sources was also the subject of Batzaria's last known radio conference, aired in August 1935.[138] A few months later, he was appointed Commissioner of the Luna Bucureștilor ("Bucharest Month") festival. This activity required that he and Iuliu Scriban inaugurate a "Lilliput", set up by entertainers with dwarfism.[139]

Right-wing radical sympathies

[edit]In 1935, Batzaria was still taking a stand against the extremes of Romanian nationalism, and specifically against positive discrimination in support of native Romanians. At the time, he argued that it was "quite difficult to draw a clear distinction between true Romanians and foreign, Romanianized, elements"—suggesting that many outspoken nationalists were themselves included in the latter category.[140] In mid 1936, he parted with Dimineața and joined its right-wing and nationalist rival, Universul, also becoming its publisher.[141] The nationalist priest Ioan Moța welcomed him there, claiming that Batzaria had stood up to Jewish and anti-Romanian interests operating through Adevărul, having been a "white flower in that swamp".[142]

Batzaria was afterward appointed editor of Universul Copiilor ("Children's Universe"), the Universul youth magazine, which took up his Haplea stories and comics. According to literary critic Gabriel Dimisianu, who was a fan of the magazine in his boyhood, Universul Copiilor was "very good".[143] At Universul, he became involved in political disputes facing the leftists and rightists, always siding with the latter. As observed by historian Lucian Boia, this was a common enough tendency among the Aromanian elite and, as Batzaria himself put it in one of his Universul texts, was read as a "strengthening of the Romanian element."[144] The writer also became directly involved in the conflict opposing Universul and Adevărul, during which the latter was accused of being a tool for "communism". He urged the authorities to repress what he argued was a communist conspiracy, led by his former employers.[145]

In manifest contrast to Adevărul, and in agreement with Romanian fascists, Batzaria supported the Italian invasion of Abyssinia as a step forward for "that sound and creative Latin civilization."[146] Batzaria also expressed sympathy toward the fascist and antisemitic "Iron Guard" movement. This political attitude touched his editorial pieces concerning the Spanish Civil War. He marked the death of Iron Guardist politico Ion Moța, in service to the Francoist side, likening him to heroes such as Giuseppe Garibaldi and Lafayette (see Funerals of Ion Moța and Vasile Marin).[147] Ahead of the student congress, held at Târgu Mureș in September 1937, Batzaria contended that Transylvania was at the mercy of non-Romanian industrialists, arguing: "Attempts to create a [native] middle class cannot succeed as long as Romania fights against foreigners only in theory, while embracing them in fact, by buying from their institutions and companies. [...] It must not be forgotten [...] that all kinds of contemporary subversive movements, including revisionism, communism, sectarianism, are supported by our money." His position was quoted and ridiculed in the Hungarian paper Reggeli Ujság: "Mr. Bazaria [...] admitted that we are communists, revisionists, and sectarians, but he finds the adjective 'anarchist' excessive and therefore omits it".[148]

While Iorda began developing Haplea more independently, producing a series of radio plays in the late 1930s, without Batzaria's involvement,[118] the latter was turning his attention back toward Turkish topics. An article he published in July 1939 focused on the obscure noun Aliotman, once used by Romanian poets such as Vasile Alecsandri and Mihai Eminescu to designate the Ottoman realm. His hypothesis, that it was a spontaneous creation, was challenged by scholar Liviu Marian, who located its origin in a 19th-century tract by Dimitrie Cantemir.[149] In late April 1940, Batzaria translated and prefaced a volume by the Bulgarian Atanas Manov, which dealt with the Gagauz and their ultimate origin.[150] Around that time, he was secretly employed as a censor of manuals sent in from the Republic of Turkey to be used by Turco-Romanian students. He later expressed admiration for the Turkish authorities, since the textbooks featured no anti-Romanian text, and since they had self-censored all praise of Kemalism.[58] At the Balkaniad Tour, held in Bucharest in May 1940, he was an official of the Romanian Cycling Federation, personally welcoming the Hellenic and Turkish teams.[151]

The early stages of World War II saw Batzaria involved in debates about the future of Romanian identity in Transylvania. In June 1940, Universul and Plaiuri Săcelene carried his article on the economic failure of sedentarization among the ethnic Romanian Mocani. His claim was that non-Romanians had been deprived of fertile land through an egotistic action by members of other ethnic groups; this conclusion was disputed by economist I. Gârbacea, who argued that the Mocani had been deprived of their lifestyle through over-education, as endorsed by successive Romanian governments.[152] Weeks after, the region's northern parts were sectioned off and assigned to the Kingdom of Hungary, under the Second Vienna Award. Despite his political profile, Batzaria was marginalized by two successive fascist regimes—the Iron Guard's National Legionary State, followed by the authoritarian system of Conducător Ion Antonescu.[153] He was still featured and reviewed in an issue of Familia magazine, where he discussed divided Transylvania, and compared the plight of its inhabitants with that of the Aromanians.[154] His 50th book of stories also saw print, as Regina din Insula Piticilor ("The Queen of Dwarf Island"), set to coincide with Christmas 1940.[155] He also put out the Universul children's almanac.[156]

Wartime propaganda, persecution, and death

[edit]In 1942, after the Guard's downfall, Familia published Batzaria's posthumous homage to Iorga, who had been assassinated by the Guard in 1940.[157] From November 1942, Universul hosted a new series of his political articles, on the subject of "Romanians Abroad". Reflecting the Antonescu regime's rekindled interest in the Aromanian issue, these offered advice on standardizing the official Aromanian dialect.[158] In July 1943, he was a guest speaker at Iorga's people's university, in Vălenii de Munte.[10] In addition to his work as editor, Batzaria focused on translating stories by the Danish author Hans Christian Andersen, which saw print under the Moș Ene signature in stages between 1942 and 1944.[112] Under the same pen name, he published the 1943 Lacrimile mamei ("Mother's Tears"), a "novel for children and the youth".[159] At around that time, Universul Copillor began contributing to Antonescu's propaganda effort, supporting Romania's Eastern Front efforts, against the Soviet Union.[160][161] With its comics and its editorial content, the magazine spearheaded a xenophobic campaign, targeting the Frenchified culture of the upper class, ridiculing the Hungarians of Northern Transylvania, and portraying the Soviets as savages.[161]

The war's end and the rise of the Communist Party made Batzaria a direct target for political persecution. Shortly after the August 23 Coup, the communist press began targeting Batzaria with violent rhetoric, calling for his exclusion from the Romanian Writers' Society (or SSR): "in 1936, when Ana Pauker stood trial, [Batzaria] joined the enemies of the people, grouped under Stelian Popescu's quilt at Universul, instigating in favor of racial hatred".[162] The party organ, Scînteia, identified Universul Copiilor as a "fascist and anti-Soviet" publication, noting: "The traitor Batzaria, aka Moș Nae, should be aware that there is no longer a place for him in today's Romanian media."[160] Panning Lacrimile mamei for the same newspaper in November 1944, novelist Ion Călugăru assessed that Batzaria had combined "an obvious lack of talent, a false sentimentality, an artificial composition, [and] reactionary tendencies." Călugăru sampled portions of the text which "slandered" the Red Army, noting that Batzaria joined up with the "fascist offensive" during his Universul years; the book needed to "vanish from the bookshops, and soon."[163]

Batzaria was stripped of his SSR membership in the early months of 1945,[164] and banned from working in the press through an official decree on July 11.[165] He was one of the "journalists and writers engaged in incitement during Antonescu's hate-mongering rule" who were stripped of their voting rights ahead of legislative elections in November 1946.[166] The consolidation of a communist regime in 1947–1948 led to Batzaria's complete ostracizing, beginning when he was forced out of his house by the authorities (an action which reportedly caused the destruction of all his manuscripts through neglect).[153] Universul Copiilor was entirely suppressed in 1946,[143] but appeared again in 1948, as one of two children's magazines vetted by the regime (alongside Licurici). That year, Scînteia reader Lucian Mustață published an op-ed, censuring Universul Copiilor for distributing low culture and for not contributing to the consolidation of a "socialist society".[167]

Sources diverge on events occurring during Batzaria's final years. Several authors mention that he became a political prisoner of the communists.[8][15][125][168][169] According to Karpat, Batzaria died in poverty at his Bucharest house during the early 1950s.[153] Later research suggests that this occurred in 1952, at a concentration camp. The most specific such sources mention that his life ended at a penal facility located in Bucharest's Ghencea district.[8][168] Scientist Claudiu Mătasă, who shared his cell there, recalled: "His stomach ill, [Batzaria] basically died in my arms, with me taking as much care of him as circumstances would allow..."[168] Barbu Cioculescu gives a more complex account: "In very old age [Batzaria] was arrested, not for being a right-wing man, as he had not in fact been one, but for having served as a city councilor. A spinal cancer sufferer, he died in detention [...] not long after having been sentenced".[15] According to historian of journalism Marin Petcu, Batzaria's confinement was effectively a political assassination.[170]

Work

[edit]Fiction

[edit]As argued by poet-anthologist Hristu Cândroveanu, Batzaria already generated "Homeric laughter" with his Părăvulii. Echoing Anton Pann and his "Oriental wisdom", they include an episode in which Aromanians attempt to circumvent rules imposed by the immigration authorities.[19] Lifetime editions of Batzaria's work include some 30 volumes, covering children's, fantasy and travel literature, memoirs, novels, textbooks, translations, and various reports.[171] According to his profile at the University of Florence Department of Neo-Latin Languages and Literatures, Batzaria was "lacking in originality but [was] a talented vulgarizer".[8] Writing in 1987, children's author Gica Iuteș claimed that the "most beautiful pages" in Batzaria's work were those dedicated to the youth, making Batzaria "a great and modest friend of the children".[117]

Batzaria's short stories for children generally build on ancient fairy tales and traditional storytelling techniques. A group among these accounts retell classics of Turkish, Arabic and Persian literatures (such as One Thousand and One Nights), intertwined with literary styles present throughout the Balkans.[171] This approach to Middle Eastern themes was complemented by borrowings from Western and generally European sources, as well as from the Far East. The Povești de aur series thus includes fairy tales from European folklore and Asian folktales: Indian (Savitri and Satyavan), Spanish (The Bird of Truth), German, Italian, Japanese, Polish, Scandinavian and Serbian.[122] Other works retold modern works of English children's literature, including Hugh Lofting's Doctor Dolittle.[15] His wartime renditions from Andersen's stories covered The Emperor's New Clothes, The Ugly Duckling and The Little Mermaid.[112]

Among the writer's original contributions was a series of novels for the youth. According to literary critic Matei Călinescu, who recalled having enjoyed these works as a child, they have a "tearjerker" and "melodramatic" appeal.[121] Essayist and literary historian Paul Cernat calls them "commercial literature" able to speculate public demand, and likens them to the texts of Mihail Drumeș, another successful Aromanian author (or, beyond literature, to the popular singer Jean Moscopol).[172] Other stories were humorous adaptations of the fairy tale model. They include Regina din Insula Piticilor, in which Mira-Mira, Queen of the Dolls, and her devoted servant Grăurel fend off the invasion of evil wizards.[155] Batzaria is also credited with having coined popular children's rhymes, such as:

Sunt soldat și călăreț, |

I'm a soldier and a cavalryman, |

Batzaria's Haplea was a major contribution to Romanian comics culture and interwar Romanian humor, and is ranked by comics historiographer Dodo Niță as the top Romanian series of all times.[114] The comics, the books and the animated film all ridicule the boorish manners of peasants and add comic effect to the clash of cultures between city and village lives.[115] The scripts were not entirely original creations: according to translator and critic Adrian Solomon, one Haplea episode retold a grotesque theme with some tradition in the Romanian folklore (the story of Păcală), that in which the protagonist murders people for no apparent reason.[174] As noted by Batzaria reviewers, Pann was also an influence in developing Haplea.[116]

Memoirs and essays

[edit]A large segment of Batzaria's literary productions was made up of subjective recollections. Karpat, according to whom such writings displayed the attributes of "a great storyteller" influenced by both Romanian classic Ion Creangă and the Ottoman meddahs, notes that they often fail to comply with orthodox attested timelines and accuracy checks.[175] Reviewing În închisorile turcești, journalist D. I. Cucu recognized Batzaria as an entertaining raconteur, but noted that the text failed to constitute a larger fresco of the Aromanian "denationalization".[91] More such criticism came from Batzaria's modernist contemporary Felix Aderca, who suggested that Batzaria and Iorga (himself an occasional writer) had "compromised for good" the notion of travel literature.[176] Cucu described the account as entirely opposed to the romanticized narratives of Ottoman affairs, by Pierre Loti or Edmondo De Amicis.[91] Novelist Mihail Sadoveanu similarly argued that Batzaria, who lacked Loti's "brilliant style", was "more real" and less self-absorbed in his accounts. His own "pages of literature" were in Spovedanii de cadâne, which dwells on the "sadness of seraglios", introducing Romanians to historical figures such as Yusuf Agha and Edhem Pasha.[177]

The main book in this Ottomanist series is Din lumea Islamului. Turcia Junilor Turci ("From the World of Islam. The Turkey of the Young Turks"), which traces Batzaria's own life in Macedonia and Istanbul. Its original preface was a contribution of Iorga, who recommended it for unveiling "that interesting act in the drama of Ottoman decline that was the first phase of Ottoman nationalism".[9] In Karpat's opinion, these texts bring together the advocacy of liberalism and Westernization, flavored with "a special understanding of the Balkan and Turkish societies".[171] Batzaria's books also describe Christianity as innately superior to Islam, better suited for modernization and education, over Islamic fatalism and superstition.[9][178] His extended essay on women's rights and Islamic feminism, Karpat argues, shows that the Young Turks' modernizing program anticipated the Kemalist ideology of the 1920s.[92] Overall, Batzaria gave voice to an anticlerical agenda targeting the more conservative ulema, but also the more ignorant of Christian priests, and discussed the impact of religious change, noting that the Young Turks eventually chose a secular identity over obeying their Caliphate.[179]

În închisorile turcești and other such writings record the complications of competing nationalisms in Ottoman lands. Batzaria mentions the Albanian landowners' enduring reverence for the Ottoman Dynasty, and the widespread adoption of the vague term "Turk" as self-designation in the Balkan Muslim enclaves.[180] Likewise, he speaks about the revolutionary impact of ethnic nationalism inside the Rum Millet, writing: "it was not rare to see in Macedonia a father who would call himself a Greek without actually being one [...], while one of his sons would become a fanatical Bulgarian, and the other son would turn into a killer of Bulgarians."[181] While theorizing an Aromanian exception among the "Christian peoples" of the Ottoman-ruled Balkans, in that Aromanians generally worked to postpone the evident Ottoman decline, Batzaria also argued that the other ethnic groups were innately hostile to the Young Turks' liberalism.[181] However, Karpat writes, "Batzaria believed, paradoxically, that if the Young Turks had remained genuinely faithful to their original liberal ideals they might have succeeded in holding the state together."[181]

According to Batzaria, the descent into civil war and the misapplication of liberal promises after the Young Turk Revolution made the Young Turk executive fall back on its own ethnic nationalism, and then on Turkification.[9][182] That policy, the author suggested, was ineffective: regular Turks were poor and discouraged, and Europe looked with displeasure on the implicit anti-colonialism of such theories.[183] In Din lumea Islamului, Batzaria looks to the individuals who pushed for this policy. He traces psychological sketches of İsmail Enver (who, although supportive of a "bankrupt" Pan-Turkic agenda, displayed "an insane courage and an ambition that kept growing and solidifying with every step"), Ahmed Djemal (an uncultured chauvinist), and Mehmed Talat ("the most sympathetic and influential" of the Young Turk leaders, "never bitten by the snake of vanity").[9]

Batzaria also noted that Turkification alienated the Aromanians, who were thus divided and forced to cooperate with larger ethnic groups within the Rum Millet just before the First Balkan War, and that cooperation between them and the Bulgarians was already unfeasible before the Second War.[184] According to Betzaria's anecdotal account, he and the Ottoman Armenian politician Gabriel Noradunkyan rescued Istanbul from a Bulgarian siege, by spreading false rumors about a cholera epidemic in the city.[9] His explanation of World War I depicts the Central Powers alliance as a gamble by the most daring of the Young Turks.[185] Deploring the repeated acts of violence perpetrated by the Ottomans against members of the Armenian community (Noradunkyan included),[9] Batzaria also maintains that the Armenian genocide was primarily an endeavor of rogue Ottoman Army units, Hamidieh regiments and other Kurds.[9][186] He claims to have unsuccessfully asked the Ottoman Senate to provide Armenians with weaponry against the "bandits carrying a firman".[9]

In other works, Batzaria expanded his range, covering the various problems of modernity and cultural identity. România văzută de departe, described by Cucu as a "balm" for patriotic feeling, illustrated with specific examples the hopes and aspirations of philo-Romanians abroad: a Romanian-Bulgarian priest, a Timok Romanian mayor, an Aromanian schoolteacher, etc.[94] The 1942 series of essays offered some of Batzaria's final comments on the issue of Aromanian politics. Although he offered implicit recognition of the existence of an "Aromanian dialect", Batzaria noted that Romanian had always been seen by him and his colleagues as the natural expression of Aromanian culture.[158] On the occasion, he referred to "the Romanian minorities" of the Balkans as "the most wronged and persecuted" Balkan communities.[187]

Legacy

[edit]Batzaria's contributions as a writer underwent critical reevaluation during the last decades of the communist regime, when Romania was ruled upon by Nicolae Ceaușescu. Writing at the time, Karpat argued: "Lately there seems to be a revived interest in [Batzaria's] children's stories."[153] In a 1968 memoir of childhood and its pastimes, communist poet Veronica Porumbacu spoke of Batzaria as "my weekly friend".[188] During that period, Romania's literary scene included several authors whose talents had been first noticed by Batzaria when, as children, they sent him their debut works. Such figures include Ștefan Cazimir,[97] Barbu Cioculescu,[189] Mioara Cremene,[190] and Tudor George.[191] Iorda reprised Haplea with a short comic book that appeared in 1971;[192] in this incarnation, the captions were penned by another humorist, Tudor Mușatescu.[118] Batzaria's works for junior readers were published in several editions beginning in the late 1960s,[153] and included reprints of Povești de aur with illustrations by Lívia Rusz.[193] Writing the preface to one such reprint, Gica Iuteș defined Batzaria as "one of the eminent Aromanian scholars" and "a master of the clever word", while simply noting that he had "died in Bucharest in the year 1952".[194] Similarly, the 1979 Dicționarul cronologic al literaturii române ("Chronological Dictionary of Romanian Literature") discussed Batzaria, but gave no clue as to his death.[125]

An Aromanian-themed Radio Romania show, aired in April 1984, included a record of Toma Caragiu reciting from the Părăvulii.[195] In 1985, Cândroveanu hosted samples from the same work in his anthology of Aromanian poems.[19][20] In an overview published that same year, critic Viniciu Gafița assessed that Batzaria was one of the authors without whom "childhood can't even be imagined".[196] These editions ran parallel to those put out in Fayetteville, New York by Tiberius Cunia, which Cândroveanu chronicled in Luceafărul.[19] In tandem with this official recovery, Batzaria's work became an inspiration for the dissident poet Mircea Dinescu, the author of a clandestinely circulated satire which compared Ceaușescu to Haplea and referred to both as figures of destruction.[197][198]

Soon after the 1989 Revolution, which signified the communist regime's end, a magazine called Universul Copiilor was launched by Elena Mănescu, whose own son had been killed during the events.[199] Renewed interest in Batzaria's work came at this stage. It was integrated into new reviews produced by literary historians, and awarded a sizable entry in the 2004 Dicționar General al Literaturii Române ("The General Dictionary of Romanian Literature"). The character of this inclusion produced some controversy: taking Batzaria's entry as a study case, critics argued that the book gave too much exposure to marginal authors, at the detriment of writers from the Optzeciști generation (whose respective articles were comparatively shorter).[200][201] The period saw a number of reprints from his work, including the Haplea comics[113] and a 2003 reissue of his Haplea la București ("Haplea in Bucharest"), nominated for an annual prize in children's fiction.[202] Fragments of his writings, alongside those of Cândroveanu, George Murnu, and Teohar Mihadaș, were included in the Romanian Academy's standard textbook for learning Aromanian (Manual de aromână-Carti trâ învițari armâneaști, edited by Matilda Caragiu Marioțeanu and printed in 2006).[203] On April 10, 2016, the Trâ Armânami Association of French Aromanians formally inaugurated the N. C. Batzaria Aromanian Library (Vivliutikeia Armãneascã N. C. Batzaria) in Paris, France.[204] It was firstly founded in 2015 by Nicolas Trifon and Niculaki Caracota.[205] Haplea continued to appear in comic strips: in 2019, Viorel Pârligras was reusing the character in strips published by a Craiova newspaper.[206]

The writer was survived by daughter Florica (sometimes credited as "Rodica")[153] who died in November 1968.[207] As a child, she was present when Batzaria visited Brașov in 1913.[71] She spent much of her life abroad, and was for a while married to painter Nicolae Dărăscu.[15][208] As "Florica Dărăscu", she also contributed to her father's Dimineața Copiilor.[209] The writer's nephew, Vangheli Mișicu, was employed as an engineer in Galați, where in the 1930s he was putting out the trade magazine Arte și Meserii.[5] In October 1970, Mișicu obtained that Nicolae Batzaria's remains be reburied at Reînvierea Cemetery Plot 15, in Colentina; a ceremony was scheduled on November 1.[210] Batzaria's great-granddaughter, Dana Schöbel-Roman, was a graphic artist and illustrator, who worked with children's author Grete Tartler on the magazine Ali Baba (printed in 1990).[211]

Notes

[edit]- ^ a b c d Zbuchea (1999), p. 79

- ^ Cordescu, pp. 56–57, 59

- ^ "Informațiuni", in Biserica și Școala, Issue 18/1942, p. 151

- ^ Batzaria (1932), p. 1

- ^ a b c d e Batzaria (1932), p. 2

- ^ Cordescu, p. 192

- ^ Karpat, p. 563; Zbuchea (1999), pp. 62–63, 79. See also Batzaria (1942), pp. 37–39

- ^ a b c d e f g (in Romanian) "Batzaria Nicolae", biographical note in Cronologia della letteratura rumena moderna (1780-1914) database, at the University of Florence's Department of Neo-Latin Languages and Literatures; retrieved August 19, 2009

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r Eduard Antonian, "Turcia, Junii Turci și armenii în memoriile lui Nicolae Batzaria", in Ararat, Issue 8/2003, p. 6

- ^ a b "Deschiderea cursurilor Universității populare 'Nicolae Iorga' de la Vălenii de Munte", in Universul, July 17, 1943, p. 5

- ^ Batzaria (1942), pp. 37–38

- ^ a b c Batzaria (1942), p. 41

- ^ a b Karpat, p. 563

- ^ Lascu, pp. 52–53

- ^ a b c d e f (in Romanian) Barbu Cioculescu, "Soarele Cotrocenilor", in Litere, Issue 2/2011, p. 11

- ^ a b c d Zbuchea (1999), p. 82

- ^ a b Zbuchea (1999), pp. 81–82

- ^ Gică, p. 6. See also Batzaria (1932), p. 2

- ^ a b c d e f Hristu Cândroveanu, "Mapamond. Părăvuliile lui Batzaria", in Luceafărul, Vol. XXXII, Issue 45, November 1989, p. 8

- ^ a b Șerban Cioculescu, "Breviar. Un veac de poezie aromână (II)", in România Literară, Issue 48/1985, p. 7

- ^ Cordescu, pp. 84, 191, 204. See also Karpat, p. 563; Zbuchea (1999), pp. 79–80

- ^ Mihail Guboglu, "Contemporanul enciclopedic. Mustafa Kemal Atatürk", in Contemporanul, Issue 21/1983, p. 5

- ^ a b c Zbuchea (1999), p. 80

- ^ Hanioğlu, p. 259; Karpat, p. 563; Zbuchea (1999), pp. 79, 82

- ^ a b c Gheorghe Zbuchea, "Varieties of Nationalism and National Ideas in Nineteenth- and Twentieth-Century Southeastern Europe", in Răzvan Theodorescu, Leland Conley Barrows (eds.), Studies on Science and Culture. Politics and Culture in Southeastern Europe, UNESCO-CEPES, Bucharest, 2001, p. 247. OCLC 61330237

- ^ Zbuchea (1999), pp. 63–65

- ^ Zbuchea (1999), pp. 80–81

- ^ Zbuchea (1999), pp. 80, 81. See also Batzaria (1942), p. 41

- ^ a b c d Gică, p. 7

- ^ Gică, pp. 6–7

- ^ a b c d Gică, p. 6

- ^ Zbuchea (1999), pp. 58, 81. See also Gică, pp. 6–7

- ^ Zbuchea (1999), p. 81

- ^ Karpat, pp. 567–568

- ^ Gică, p. 8; Zbuchea, pp. 67, 72–73, 84, 85, 90, 94–95, 116, 139, 142, 191–192, 241, 265

- ^ Cordescu, pp. 205, 206, 247

- ^ "Corespondență din Salonic", in Universul, May 19, 1905, p. 2

- ^ Cordescu, pp. 197–198

- ^ C., "Scarta aromînilor. — Ce spune președintele comunitățeĭ romîne din Salonic", in Adevărul, July 27, 1908, p. 1

- ^ Zbuchea (1999), p. 82. See also Gică, pp. 7–8

- ^ Gică, pp. 7–8

- ^ a b (in Aromanian) Agenda Armâneascâ, at Radio Romania International, April 14, 2009; retrieved August 20, 2009

- ^ M. E., "Note", in Revista Fundațiilor Regale, Issue 4/1940, p. 235

- ^ Karpat, p. 563; Zbuchea (1999), pp. 78–79, 82–84

- ^ Karpat, pp. 563, 569. See also Zbuchea (1999), pp. 79, 83–84

- ^ Karpat, p. 569

- ^ Karpat, pp. 571–572

- ^ Hanioğlu, pp. 259–260

- ^ Hanioğlu, p. 260

- ^ "Manifestațiile aromînilor — Tinerii turci și aromînii — Manifestație de simpatie inspectorului școalelor aromîne", in Adevărul, July 25, 1908, p. 2

- ^ "Dela frați. Campania electorală a românilor macedoneni", in Tribuna, Vol. XII, Issue 197, September 1908, p. 4

- ^ Hanioğlu, p. 259; Karpat, pp. 563, 569, 571, 576–577. See also Lascu, p. 56; Zbuchea (1999), pp. 78–79, 83–84

- ^ Zbuchea (1999), pp. 83–84, 283

- ^ "Noutăți. Școale românești în Turcia", in Olteanul, Issue 5/1909, p. 6

- ^ Batzaria (1942), pp. 38–39

- ^ Karpat, pp. 563–564

- ^ Zbuchea (1999), pp. 84–99, 109

- ^ a b N. Batzaria, "Tratamentul minorităților românești", in Universul, July 28, 1943, p. 1

- ^ R. A. Guys, "Soluția chestieĭ albaneze. Un important articol al senatorului romîn Batzaria", in Adevărul, July 13, 1911, pp. 1–2

- ^ "Criza din Turcia", in Adevărul, January 4, 1912, p. 5

- ^ Zbuchea (1999), pp. 83, 99–101, 143–144, 146, 155

- ^ Zbuchea (1999), pp. 100–101, 155–156

- ^ R. A. Guys, "Meetingurile războinice din Constantinopol. Un orator cere cucerirea limitelor naturale ale Turciei, cari sînt țărmurile Dunărei, a spus dînsul", in Adevărul, September 25, 1912, p. 3

- ^ N. Batzaria, "O amintire despre Ion I. C. Brătianu", in Universul, November 28, 1940, pp. 1–2

- ^ Gică, pp. 7, 8

- ^ Hanioğlu, p. 468; Karpat, p. 564. See also Zbuchea (1999), pp. 83, 84

- ^ "Decorarea mnistrului Batzaria", in Universul, April 26, 1913, p. 1

- ^ a b c "Gobbles" (with biographical notes), in Plural Magazine, Issue 30/2007

- ^ Karpat, pp. 564, 569–570; Zbuchea (1999), p. 79

- ^ Zbuchea (1999), p. 84

- ^ a b "Un Ardelean despre un Macedonean", in Neamul Românesc, Vol. IX, Issue 3, January 1914, pp. 5–6

- ^ (in Romanian) "Informațiuni", in Românul (Arad), Issue 32/1914, p. 8

- ^ Zbuchea (1999), pp. 109–110

- ^ Karpat, pp. 564, 580; Zbuchea (1999), pp. 108–109. See also Hanioğlu, p. 468

- ^ Karpat, p. 580; Zbuchea (1999), p. 109

- ^ Karpat, pp. 564, 580

- ^ "Külföld. A török belügyminiszter Bukarestben", in Az Ujság, May 5, 1914, p. 7

- ^ "Serviciul telegrafic și telefonic al Opiniei. Talaat Bay in Capitală", in Opinia, May 13, 1914, p. 3

- ^ Nicolae Iorga, "Vaida și Bațaria", in Neamul Românesc, Vol. IX, Issue 30, August 1914, p. 1

- ^ "Turcia pentru Austro-Ungaria", in Opinia, July 17, 1914, p. 1

- ^ Karpat, pp. 577–584

- ^ "The Ottoman Parliament. 13th session, Jan. 16th", in The Orient, Vol. VI, Issue 3, January 1915, p. 23

- ^ "Die Demission türkischer Senatoren", in Pester Lloyd, January 19, 1915, p. 6

- ^ G. M. Doro, "Turcia și războiul. Interview cu fostul ministru turc d. N. Batzaria", in Adevărul, January 13, 1915, p. 3

- ^ "Parlamentul. Ședințele dela 28 Ianuarie. Senatul", in Universul, January 30, 1915, p. 4

- ^ "Nota zilei. Batzarisme", in Opinia, June 28, 1915, p. 1

- ^ "Adunarea dela societatea macedo-română", in Adevărul, July 10, 1916, p. 2

- ^ Karpat, p. 564; Zbuchea (1999), p. 84

- ^ a b "Știri", in Neamul Românesc, June 24, 1923, p. 3

- ^ (in Romanian) G. Brătescu, "Uniunea Ziariștilor Profesioniști, 1919–2009. Compendiu aniversar", in Mesagerul de Bistrița-Năsăud, December 11, 2009

- ^ a b c (in Romanian) D. I. Cucu, "Cărți și reviste. N. Batzaria, În închisorile turcești", in Gândirea, Issue 11/1921, p. 211

- ^ a b Karpat, p. 567

- ^ (in Romanian) N. Batzaria, "Vecina dela San-Stefano", in Gândirea, Issue 5/1922, pp. 90–93

- ^ a b (in Romanian) D. I. Cucu, "Cărți și reviste. N. Batzaria, România văzută de departe", in Gândirea, Issue 4/1922, pp. 80–81

- ^ Karpat, p. 564; Zbuchea (1999), p. 79

- ^ (in Romanian) "Frontul Democratic", in Chemarea Tinerimei Române, Issue 23/1926, p. 23

- ^ a b (in Romanian) Ștefan Cazimir, "Dimineața copilului", in România Literară, Issue 19/2004

- ^ (in Romanian) Alexandru Hodoș, "Însemnări. Însușiri profesionale", in Țara Noastră, Issue 13/1926, p. 423

- ^ Marilena Oana Nedelea, Alexandru Nedelea, "Law of 24 June 1925 – Administrative Unification Law. Purpose, Goals, Limits", in the Ștefan cel Mare University of Suceava's Annals (Fascicle of The Faculty of Economics and Public Administration), Issue 1 (13)/2011, p. 346

- ^ (in Romanian) Șt. Peneș, "Jos masca Domnule Batzaria!", in Înfrățirea Românească, Issue 19/1929, pp. 221–222

- ^ Iorga (1939), p. 230

- ^ Petcu, p. 60

- ^ (in Romanian) Traian D. Lazăr, "Din istoricul Societății de Cultură Macedo-române", in Revista Română (ASTRA), Issue 3/2011, pp. 23–24

- ^ (in Romanian) Delavardar, "Raiul aromânilor", in Cultura Poporului, Issue 6/1924, p. 1

- ^ (in Romanian) N. Batzaria, "Minoritățile etnice din Peninsula Balcanică", in Societatea de Mâine, Issues 25–26, June–July 1927, pp. 323–325

- ^ Iorga (1939), p. 353

- ^ D. Antohi, "Problema coloniștilor macedoneni din Cadrilater. Adunarea generală a Societății Macedo-Române din Capitală", in Universul, September 27, 1929, p. 5

- ^ (in Romanian) Dumitru Hîncu, "Al. Tzigara-Samurcaș – Din amintirile primului vorbitor la Radio românesc", in România Literară, Issue 42/2007

- ^ Maria Bucur, "Romania", in Kevin Passmore (ed.), Women, Gender, and Fascism in Europe, 1919–45, p. 72. Manchester: Manchester University Press, 2003. ISBN 0-7190-6617-4

- ^ (in Romanian) "Ancheta ziarului Universul 'Să se înscrie femeile în partidele politice?', Ziarul Nostru, anul IV, nr. 2, februarie 1930", in Ștefania Mihăilescu, Din istoria feminismului românesc: studiu și antologie de texte (1929-1948), p. 116. Iași: Polirom, 2006. ISBN 973-46-0348-5

- ^ Batzaria (1987), passim; Karpat, p. 564

- ^ a b c Mihaela Cernăuți-Gorodețchi, notes to Hans Christian Andersen, 14 povești nemuritoare, pp. 20, 54, 78, 103. Iași: Institutul European, 2005. ISBN 973-611-378-7

- ^ a b (in Romanian) Maria Bercea, "Incursiune în universul BD", in Adevărul, June 29, 2008

- ^ a b Ioana Calen, "Cărtărescu e tras în bandă – Provocarea desenată", in Cotidianul, June 13, 2006

- ^ a b c d e (in Romanian) Alex Aciobăniței, "Filmul românesc între 1905–1948 (18). Arta animației nu a început cu Gopo!", in Timpul, Issue 72/2004, p. 23

- ^ a b (in Romanian) Ion Băilă, "Literatură pentru copii. Haplea de N. Batzaria", in Societatea de Mâine, Issues 49–50, December 1926, p. 766

- ^ a b c Iuteș, in Batzaria (1987), p. 3

- ^ a b c Carol Isac, "Scurtă istorie a unui personaj", in Steagul Roșu, June 3, 1973, p. 3

- ^ a b Mușețeanu, pp. 41–42

- ^ Gheorghe Vlădescu-Răcoasa, "Prima Conferință Interbalcanică", in Arhiva pentru Știință și Reformă Socială, Issues 1-3/1930, p. 394

- ^ a b Matei Călinescu, Ion Vianu, Amintiri în dialog. Memorii, p. 76. Iași: Polirom, 2005. ISBN 973-681-832-2

- ^ a b Batzaria (1987), passim

- ^ (in Romanian) "Cărți școlare", in Învățătorul, Special Issue, August 20, 1930, p. 37

- ^ Vartan Arachelian, "Iorga și Siruni, sau fericita întâlnire a doi savanți", in Munca unui savant armean în România: Hagop Djololian Siruni, pp. 17–18. Bucharest: Editura Biblioteca Bucureștilor, 2008. ISBN 978-973-8369-25-2

- ^ a b c (in Romanian) Barbu Cioculescu, "Cum se citește un dicționar", in Luceafărul, Issue 33/2011

- ^ Dem I. Dobrescu, "Eftenirea vieții prin comitetele cetățenești", in Curentul, November 1, 1941, p. 1

- ^ "Kinevezték Aradi egye új prefektusát. Maicanescu Miklós ezredes, az új prefektus, dobrudzsát származású aktív katonatiszt. Az új prefektusok névsora. Dimitrescu Constantin: Készen állok, hogy átadjam helyemet", in Aradi Közlöny, April 25, 1931, p. 3; "Ultima Oră. Nouii prefecți", in Lupta, April 25, 1931, p. 4

- ^ "Elgurult milliók. Vakovíci közlekedési miniszter szenzációs leleplezése * Csaknem tízmilliónyi összeget vettek fel jogtalanul a CFR-nél * Cigareanu Livius Manoilescu miatt kilépett a nemzeti parasztpártból * Maniuék a parlament feloszlatásakor manifesztumban fordulnak a néphez. Batzaria prefektus kerül a bánsági kormányzóság élére", in Temesvári Hirlap, April 28, 1931, p. 1

- ^ "Noui prefecți", in Cuvântul, May 8, 1931, p. 3; "Legújabb. Cioban Aurélért ma délelőtt kinevezték Temes megye prefektusává. Álhírek a kormány lemondásáról", in Temesvári Hirlap, May 8, 1931, p. 7

- ^ "Ultima oră. 'Biciul de foc' al d-lui Duca și imprudența d-lui Batzaria", in Neamul Românesc, March 29, 1932, p. 4

- ^ "Tablou indicând rezultatele pe circumscripții electorale ale alegerilor pentru Adunarea deputaților, efectuate în ziua de 20 Decembrie 1933", in Monitorul Oficial, Issue 300/1933, p. 8003

- ^ H. Soreanu, "Reportaj parlamentar. Camera. Aspecte", in Adevărul, March 27, 1934, p. 3

- ^ "Reportaj parlamentar. Camera. Aspecte. Legea naționalității", in Adevărul, March 30, 1934, p. 5

- ^ Lascu, p. 45

- ^ Petre Matei, "Romi sau țigani? Etnonimele – istoria unei neînțelegeri", in István Horváth, Lucian Nastasă (eds.), Rom sau Țigan: dilemele unui etnonim în spațiul românesc, pp. 59–60, 62. Cluj-Napoca: Institutul pentru Studierea Problemelor Minorităților Naționale, 2012. ISBN 978-606-8377-06-3

- ^ Romulus Dianu, "Mișcarea literară. I. O restabilire istorică" and Costel C. Panaitescu, "Universitatea dela Văleni. Origina lui Anton Pann. Conferința d-lui N. Batzaria", in Rampa, July 21, 1929, p. 3

- ^ (in Romanian) Florentina Tone, "Scriitorii de la Adevĕrul", in Adevărul, December 30, 2008,

- ^ Mușețeanu, p. 42

- ^ "Inaugurarea orașului piticilor din 'Luna Bucureștior'", in Buna Vestire, May 19, 1937, p. 5

- ^ "La proposition de M. Vaïda pour l'introduction du 'numerus clausus'", in Glasul Minorităților, Issue 3/1935, pp. 61–62

- ^ Boia, pp. 66–67, 70; Karpat, p. 564

- ^ Ioan Moța, "De vorbă cu țăranii cetitori ai Universului. Nu e destul, [sic] că d. Batzaria a părăsit casa cu stafii...", in Universul, July 14, 1936, p. 3

- ^ a b (in Romanian) Mircea Iorgulescu, Gabriel Dimisianu, "Prim-plan Gabriel Dimisianu. 'Noi n-am crezut că se va termina' ", in Vatra, Issues 3–4/2005, p. 69

- ^ Boia, p. 66

- ^ Hans-Christian Maner, Parlamentarismus in Rumänien (1930–1940): Demokratie im autoritären Umfeldpp. 323–324. Munich: R. Oldenbourg Verlag, 1997. ISBN 3-486-56329-7

- ^ Boia, pp. 66–67

- ^ Valentin Săndulescu, "La puesta en escena del martirio: La vida política de dos cadáveres. El entierro de los líderes rumanos legionarios Ion Moța y Vasile Marin en febrero de 1937", in Jesús Casquete, Rafael Cruz (eds.), Políticas de la muerte. Usos y abusos del ritual fúnebre en la Europa del siglo XX, pp. 260, 264. Madrid: Catarata, 2009. ISBN 978-84-8319-418-8

- ^ "Mit tudnak a helyi román iparosok és kereskedők a kisebbségi kartársaikról?", in Reggeli Ujság, September 8, 1937, p. 2

- ^ Liviu Marian, "Aliotmanul lui Alecsandri", in Convorbiri Literare, Vol. LXXIII, Issues 7–12, July–December 1940, pp. 889–890

- ^ "Carnetul zilei. Magazin literar și artistic. Origina găgăuților", in Curentul, April 22, 1940, p. 2

- ^ "Sport. Balcaniada, marele eveniment ciclist al anului 1940. Echipa Greciei sosește Duminecă.—Suporteurii bulgari la București—F. R. C. face pregătiri asidue pentru o îngrijită organizare", in România, May 18, 1940, p. 6

- ^ I. Gârbacea, "Revista Plaiuri Săcelene", in Tribuna, Issue 108/1940, pp. 2–3

- ^ a b c d e f Karpat, p. 564

- ^ (in Romanian) N. Batzaria, "Ardeleni și Macedoneni", in Familia, Issue 1/1941, pp. 19–23

- ^ a b (in Romanian) Marieta Popescu, "Note. Regina din Insula Piticilor", in Familia, Issue 1/1941, pp. 103–104

- ^ (in Romanian) Marieta Popescu, "Revista revistelor. Calendarul Universul Copiilor 1941", in Familia, Issue 1/1941, p. 112

- ^ Batzaria (1942), passim

- ^ a b Zbuchea (1999), pp. 219–220

- ^ George Baiculescu, "Cronica bibliografică. Cărți pentru copii", in Revista Fundațiilor Regale, Issue 2/1944, p. 450

- ^ a b (in Romanian) Cristina Diac, "Comunism – Avem crime! Vrem criminali!", in Jurnalul Național, April 11, 2006

- ^ a b Lucian Vasile, "Tudorică și Andrei, eroi ai propagandei de război", in Magazin Istoric, March 2011, pp. 80–82

- ^ Victor Frunză, Istoria stalinismului în România, p. 251. Bucharest: Humanitas, 1990. ISBN 973-28-0177-8

- ^ Ion Călugăru, "Literatura pentru copii", in Scînteia, November 13, 1944, p. 2

- ^ Boia, p. 264

- ^ "Epurația în presă", in Universul, July 13, 1945, p. 3

- ^ "Nem szavazhattak az Antonescu-korszak újságírói", in Erdély, September 19, 1946, p. 2

- ^ "Cititorii au cuvântul. Despre unele desene din Universul Copiilor", in Scînteia, October 4, 1948, p. 4

- ^ a b c (in Romanian) Nicolae Dima, Constantin Mătasă, "Viața neobișnuită a unui om de știință român refugiat în Statele Unite", in the Canadian Association of Romanian Writers Destine Literare, Issues 8–9 (16–17), January–February 2011, p. 71

- ^ Boia, p. 312; Eugenio Coșeriu, Johannes Kabatek, Adolfo Murguía, "Die Sachen sagen, wie sie sind...". Eugenio Coșeriu im Gespräch, p. 11. Tübingen: Gunter Narr Verlag, 1997. ISBN 3-8233-5178-8; Zbuchea (1999), p. 79

- ^ Petcu, p. 59

- ^ a b c Karpat, p. 565

- ^ (in Romanian) Roxana Vintilă, "Un Jean Moscopol al literaturii", in Jurnalul Național, June 17, 2009

- ^ Horia Gârbea, Trecute vieți de fanți și de birlici, p. 58. Bucharest: Cartea Românească, 2008. ISBN 978-973-23-1977-2

- ^ Adrian Solomon, "The Truth About Romania's Children", in Plural Magazine, Issue 30/2007