Polynesian navigation

Polynesian navigation was used for thousands of years to make long voyages across thousands of miles of open ocean. Navigators travelled to small inhabited islands using only their own senses and knowledge passed by oral tradition from master to apprentice, often in the form of song. Compared to the European navigators, Polynesian navigation relied on skill and using the natural tools around them to travel the vast ocean and thus needed no instruments. Passed down from their ancestors before them, who never used maps or sextants, they instead read the stars and swells, observing the ocean and sky.[1] These wayfinding techniques along with their unique outrigger canoe construction methods have been kept as guild secrets. Generally each island maintained a guild of navigators who had very high status; in times of famine or difficulty they could trade for aid or evacuate people to neighboring islands. As of 2014, these traditional navigation methods are still taught in the Polynesian outlier of Taumako Island in the Solomons.

History

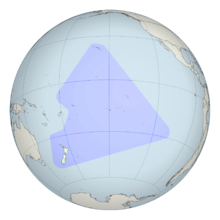

Between about 3000 and 1000 BC speakers of Austronesian languages spread through the islands of Southeast Asia – almost certainly starting out from Taiwan,[2] as tribes whose natives were thought to have previously arrived about from mainland South China about 8000 years ago – into the edges of western Micronesia and on into Melanesia. In the archaeological record there are well-defined traces of this expansion which allow the path it took to be followed and dated with a degree of certainty. In the mid-2nd millennium BC a distinctive culture appeared suddenly in north-west Melanesia, in the Bismarck Archipelago, the chain of islands forming a great arch from New Britain to the Admiralty Islands. This culture, known as Lapita, stands out in the Melanesian archeological record, with its large permanent villages on beach terraces along the coasts. Particularly characteristic of the Lapita culture is the making of pottery, including a great many vessels of varied shapes, some distinguished by fine patterns and motifs pressed into the clay. Within a mere three or four centuries between about 1300 and 900 BC, the Lapita culture spread 6000 km further to the east from the Bismarck Archipelago, until it reached as far as Tonga and Samoa.[3] In this region, the distinctive Polynesian culture developed. The Polynesians are then believed to have spread eastward from the Samoan Islands into the Marquesas, the Society Islands, the Hawaiian Islands and Easter Island; and south to New Zealand. The pattern of settlement also extended to the north of Samoa to the Tuvaluan atolls, with Tuvalu providing a stepping stone to migration into the Polynesian Outlier communities in Melanesia and Micronesia.[4][5][6]

Theories

Pre-Columbian contact with the Americas

In the mid-20th century, Thor Heyerdahl proposed a new theory of Polynesian origins (one which did not win general acceptance), arguing that the Polynesians had migrated from South America on balsa-log boats.[7][8]

The presence in the Cook Islands of sweet potato that is a plant native to the Americas (called kūmara in Māori), which have been radiocarbon-dated to 1000 CE, has been cited as evidence that Americans could have traveled to Oceania. The current thinking is that sweet potato was brought to central Polynesia circa 700 CE and spread across Polynesia from there, possibly by Polynesians who had traveled to South America and back.[9] An alternative explanation posits biological dispersal; plants and/or seeds could float across the Pacific without any human contact.[10]

A 2007 study published in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences examined chicken bones at El Arenal near the Arauco Peninsula, Arauco Province, Chile. The results suggested Oceania-to-America contact. Chickens originated in southern Asia and the Araucana breed of Chile was thought to have been brought by Spaniards around 1500. However, the bones found in Chile were radiocarbon-dated to between 1304 and 1424, well before the documented arrival of the Spanish. DNA sequences taken were exact matches to those of chickens from the same period in American Samoa and Tonga, both over 5000 miles (8000 kilometers) away from Chile. The genetic sequences were also similar to those found in Hawaiʻi and Easter Island, the closest island at only 2500 miles (4000 kilometers), and unlike any breed of European chicken.[11][12][13] Although this initial report suggested a Polynesian pre-Columbian origin a later report looking at the same specimens concluded:

A published, apparently pre-Columbian, Chilean specimen and six pre-European Polynesian specimens also cluster with the same European/Indian subcontinental/Southeast Asian sequences, providing no support for a Polynesian introduction of chickens to South America. In contrast, sequences from two archaeological sites on Easter Island group with an uncommon haplogroup from Indonesia, Japan, and China and may represent a genetic signature of an early Polynesian dispersal. Modeling of the potential marine carbon contribution to the Chilean archaeological specimen casts further doubt on claims for pre-Columbian chickens, and definitive proof will require further analyses of ancient DNA sequences and radiocarbon and stable isotope data from archaeological excavations within both Chile and Polynesia.[14]

In the last 20 years, the dates and anatomical features of human remains found in Mexico and South America have led some archaeologists[who?] to propose that those regions were first populated by people who crossed the Pacific several millennia before the Ice Age migrations; according to this theory, these would have been either eliminated or absorbed by the Siberian immigrants. However, current archaeological evidence for human migration to and settlement of remote Oceania (i.e., the Pacific Ocean eastwards of the Solomon Islands) is dated to no earlier than approximately 3,500 BP;[15] trans-Pacific contact with the Americas coinciding with or pre-dating the Beringia migrations of at least 11,500 BP is highly problematic, except for movement along intercoastal routes.

Recently, linguist Kathryn A. Klar of University of California, Berkeley and archaeologist Terry L. Jones of California Polytechnic State University have proposed contacts between Polynesians and the Chumash and Gabrielino of Southern California, between 500 and 700. Their primary evidence consists of the advanced sewn-plank canoe design, which is used throughout the Polynesian Islands, but is unknown in North America — except for those two tribes. Moreover, the Chumash word for "sewn-plank canoe," tomolo'o, may have been derived from kumulaa'au, a Hawaiian word meaning "useful tree".

In 2008, an expedition starting on the Philippines sailed two modern Wharram-designed catamarans loosely based on a Polynesian catamaran found in Auckland Museum New Zealand. The boats were built in the Philippines by an experienced boat builder to Wharram designs using modern strip plank with epoxy resin glue built over plywood frames. The catamarans had modern Dacron sails, Terylene stays and sheets with modern roller blocks. Wharram says he used Polynesian navigation to sail along the coast of Northern New Guinea and then sailed 150 miles to an island for which he had modern charts, proving that it is possible to sail a modern catamaran along the path of the Lapita Pacific migration.[16] Unlike many other modern Polynesian "replica" voyages the Wharram catamarans were not towed or escorted by a modern vessel with modern GPS navigation system, nor were they fitted with a motor.

Polynesian contact with the prehispanic Mapuche culture in central-south Chile has been suggested because of apparently similar cultural traits, including words like toki (stone axes and adzes), hand clubs similar to the Māori wahaika, the sewn-plank canoe as used on Chiloe island, the curanto earth oven (Polynesian umu) common in southern Chile, fishing techniques such as stone wall enclosures, a hockey-like game, and other potential parallels. Some strong westerlies and El Niño wind blow directly from central-east Polynesia to the Mapuche region, between Concepcion and Chiloe. A direct connection from New Zealand is possible, sailing with the Roaring Forties. In 1834, some escapees from Tasmania arrived at Chiloe Island after sailing for 43 days.[17]

Subantarctic and Antarctica

Another area of debate centers on the furthest southern extent of Polynesian expansion.

There is some material evidence of Polynesian visits to some of the subantarctic islands to the south of New Zealand, which are outside Polynesia proper. A shard of pottery has been found in the Antipodes Islands, and is now in the Te Papa museum in Wellington, and there are also remains of a Polynesian settlement dating back to the 13th century on Enderby Island in the Auckland Islands.[18][19][20][21]

The realm of legend suggests that Ui-te-Rangiora around the year 650, led a fleet of Waka Tīwai south until they reached, "a place of bitter cold where rock-like structures rose from a solid sea",[22] The brief description appears to match the Ross Ice Shelf or possibly the Antarctic mainland,[23] but may just be a description of icebergs and Pack Ice found in the Southern Ocean[24][25]

Post-colonization

Knowledge of the traditional Polynesian methods of navigation was largely lost after contact with and colonization by Europeans. This left the problem of accounting for the presence of the Polynesians in such isolated and scattered parts of the Pacific. According to Andrew Sharp, the explorer Captain James Cook, already familiar with Charles de Brosses’s accounts of large groups of Pacific islanders who were driven off course in storms and ended up hundreds of miles away with no idea where they were, encountered in the course of one of his own voyages a castaway group of Tahitians who had become lost at sea in a gale and blown 1000 miles away to the island of Atiu. Cook wrote that this incident "will serve to explain, better than the thousand conjectures of speculative reasoners, how the detached parts of the earth, and, in particular, how the South Seas, may have been peopled".[26] On his first voyage of Pacific exploration, Cook had the services of a Polynesian navigator, Tupaia, who drew a chart of the islands within a 2,000 miles (3,200 km) radius (to the north and west) of his home island of Ra'iatea. Tupaia had knowledge of 130 islands and named 74 on his chart.[27] Tupaia had navigated from Ra'iatea in short voyages to 13 islands. He had not visited western Polynesia, as since his grandfather’s time the extent of voyaging by Raiateans had diminished to the islands of eastern Polynesia. His grandfather and father had passed to Tupaia the knowledge as to the location of the major islands of western Polynesia and the navigation information necessary to voyage to Fiji, Samoa and Tonga.[28] As the Admiralty orders directed Cook to search for the “Great Southern Continent", Cook ignored Tupaia’s Chart and his skills as a navigator.

By the late 19th century to the early 20th century, a more generous view of Polynesian navigation had come into favor, creating a much romanticized view of their seamanship, canoes, and navigational expertise. Late 19th and early 20th centuries writers such as Abraham Fornander and Percy Smith told of heroic Polynesians migrating in great coordinated fleets from Asia far and wide into present-day Polynesia.[8]

Experimental research

Another view was presented by Andrew Sharp who challenged the ‘heroic vision’ hypothesis, asserting instead that Polynesian maritime expertise was severely limited in the field of exploration and that as a result the settlement of Polynesia had been the result of luck, random island sightings, and drifting, rather than as organized voyages of colonization. Thereafter the oral knowledge passed down for generations allowed for eventual mastery of traveling between known locations.[29] Sharp's reassessment caused a huge amount of controversy and led to a stalemate between the romantic and the skeptical views.[8]

By the mid-to-late 1960s it was time for a new hands-on approach. Anthropologist David Lewis sailed his catamaran from Tahiti to New Zealand using stellar navigation without instruments.[30] Anthropologist and historian Ben Finney built Nalehia, a 40-foot (12 m) replica of a Hawaiian double canoe. Finney tested the canoe in a series of sailing and paddling experiments in Hawaiian waters. At the same time, ethnographic research in the Caroline Islands in Micronesia brought to light the fact that traditional stellar navigational methods were still very much in everyday use there. The building and testing of canoes inspired by traditional designs, the harnessing of knowledge from skilled Micronesian, as well as voyages using stellar navigation, allowed practical conclusions about the seaworthiness and handling capabilities of traditional Polynesian canoes and allowed a better understanding of the navigational methods that were likely to have been used by the Polynesians and of how they, as people, were adapted to seafaring.[31] Recent re-creations of Polynesian voyaging have used methods based largely on Micronesian methods and the teachings of a Micronesian navigator, Mau Piailug.[32]

Polynesian navigators employed a whole range of techniques including use of the stars, the movement of ocean currents and wave patterns, the air and sea interference patterns caused by islands and atolls, the flight of birds, the winds and the weather.[33]

Harold Gatty suggested that long-distance Polynesian voyaging followed the seasonal paths of bird migrations. In “The Raft Book,”[34] a survival guide he wrote for the U.S. military during World War II, Gatty outlined various Polynesian navigation techniques Allied sailors or aviators wrecked at sea could use to find their way to land. There are some references in their oral traditions to the flight of birds and some say that there were range marks onshore pointing to distant islands in line with the West Pacific Flyway. A voyage from Tahiti, the Tuamotus or the Cook Islands to New Zealand might have followed the migration of the long-tailed cuckoo (Eudynamys taitensis) just as the voyage from Tahiti to Hawaiʻi would coincide with the track of the Pacific golden plover (Pluvialis fulva) and the bristle-thighed curlew (Numenius tahitiensis). It is also believed that Polynesians employed shore-sighting birds as did many seafaring peoples. One theory is that they would have taken a frigatebird (Fregata) with them. These birds refuse to land on the water as their feathers will become waterlogged making it impossible to fly. When the voyagers thought they were close to land they may have released the bird, which would either fly towards land or else return to the canoe.[33]

For navigators near the equator celestial navigation is simplified since the whole celestial sphere is exposed. Any star that passes the zenith (overhead) is on the celestial equator, the basis of the equatorial coordinate system. The stars are known by their declination, and when they rise or set they determine a bearing for navigation. For example, in the Caroline Islands Mau Piailug taught natural navigation using a star compass. The development of "sidereal compasses" has been studied[35] and theorized to have developed from an ancient pelorus.[33]

It is likely that the Polynesians also used wave and swell formations to navigate. Many of the habitable areas of the Pacific Ocean are groups of islands (or atolls) in chains hundreds of kilometers long. Island chains have predictable effects on waves and on currents. Navigators who lived within a group of islands would learn the effect various islands had on their shape, direction, and motion and would have been able to correct their path in accordance with the changes they perceived. When they arrived in the vicinity of a chain of islands they were unfamiliar with, they may have been able to transfer their experience and deduce that they were nearing a group of islands. Once they had arrived fairly close to a destination island, they would have been able to pinpoint its location by sightings of land-based birds, certain cloud formations, as well as the reflections shallow water made on the undersides of clouds. It is thought that the Polynesian navigators may have measured the time it took to sail between islands in "canoe-days" or a similar type of expression.[33]

The first settlers of the Hawaiian Islands are thought to have sailed from the Marquesas Islands using Polynesian navigation methods.[36] To test this theory, the Hawaiian Polynesian Voyaging Society was established in 1973. The group built a replica of an ancient double-hulled canoe called the Hōkūle‘a, whose crew successfully navigated the Pacific Ocean from Hawaiʻi to Tahiti in 1976 without instruments. In 1980, a Hawaiian named Nainoa Thompson invented a new method of non instrument navigation (called the "modern Hawaiian wayfinding system"), enabling him to complete the voyage from Hawaiʻi to Tahiti and back. In 1987, a Māori named Matahi Whakataka (Greg Brightwell) and his mentor Francis Cowan sailed from Tahiti to Aotearoa without instruments.

In New Zealand, a leading Māori navigator and ship builder is Hector Busby who was also inspired and influenced by Nainoa Thompson and Hokulea's voyage there in 1985.[37][38]

Notes

- ^ Clark, Liesl (15 February 2000). "Polynesia's Genius Navigators". Retrieved 17 November 2016.

- ^ Howe, K. R (2006), Vaka Moana: Voyages of the Ancestors - the discovery and settlement of the Pacific, Albany, Auckland: David Bateman, pp. 92–98

{{citation}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help) - ^ Bellwood, Peter (1987). The Polynesians – Prehistory of an Island People. Thames and Hudson. pp. 45–65.

{{cite book}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|chapterurl=(help) - ^ Bellwood, Peter (1987). The Polynesians – Prehistory of an Island People. Thames and Hudson. pp. 29 & 54.

{{cite book}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|chapterurl=(help) - ^ Bayard, D.T. (1976). The Cultural Relationships of the Polynesian Outiers. Otago University, Studies in Prehistoric Anthropology, Vol. 9.

{{cite book}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|chapterurl=(help) - ^ Kirch, P.V. (1984). The Polynesian Outiers. 95 (4) Journal of Pacific History. pp. 224–238.

{{cite book}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|chapterurl=(help) - ^ Sharp 1963, pp. 122–128.

- ^ a b c Finney 1963, p. 5.

- ^ Van Tilburg, Jo Anne (1994). Easter Island: Archaeology, Ecology and Culture. Washington, DC: Smithsonian Institution Press.

- ^ Montenegro, A.; et al. "Modeling the prehistoric arrival of the sweet potato in Polynesia" (PDF). Journal of Archaeological Science. University of Victoria. Retrieved 6 September 2011.

- ^ Whipps, Heather (June 4, 2007), "Chicken Bones Suggest Polynesians Found Americas Before Columbus", Live Science, retrieved 2007-06-05.

- ^ "Polynesians beat Spaniards to South America, study shows" by Thomas H. Maugh II, Los Angeles Times, 5 June 2007

- ^ Storey et al., " Radiocarbon and DNA evidence for a pre-Columbian introduction of Polynesian chickens to Chile" (abstract, full article available through subscription), Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 10.1073/pnas.0703993104, 7 June 2007

- ^ Indo-European and Asian origins for Chilean and Pacific chickens revealed by mtDNA. Jaime Gongora, Nicolas J. Rawlence, Victor A. Mobegi, Han Jianlin, Jose A. Alcalde, Jose T. Matus, Olivier Hanotte, Chris Moran, J. Austin, Sean Ulm, Atholl J. Anderson, Greger Larson and Alan Cooper, "Indo-European and Asian origins for Chilean and Pacific chickens revealed by mtDNA" PNAS July 29, 2008 vol. 105 no 30 [1]

- ^ Kirch, Patrick V. Background to Pacific Archaeology and Prehistory, Oceanic Archaeology Laboratory, Univ. California, Berkeley.

- ^ Klaus Hympendahl. "Lapita Voyage - The first expedition following the migration route of the ancient Polynesians". Retrieved 2 March 2016.

- ^ "Rapa Nui" (in Spanish). Retrieved 2007-06-05.

- ^ O'Connor, Tom Polynesians in the Southern Ocean: Occupation of the Auckland Islands in Prehistory in New Zealand Geographic 69 (September–October 2004): 6-8

- ^ Anderson, Atholl J., & Gerard R. O'Regan To the Final Shore: Prehistoric Colonisation of the Subantarctic Islands in South Polynesia in Australian Archaeologist: Collected Papers in Honour of Jim Allen Canberra: Australian National University, 2000. 440-454.

- ^ Anderson, Atholl J., & Gerard R. O'Regan The Polynesian Archaeology of the Subantarctic Islands: An Initial Report on Enderby Island Southern Margins Project Report. Dunedin: Ngai Tahu Development Report, 1999

- ^ Anderson, Atholl J. Subpolar Settlement in South Polynesia Antiquity 79.306 (2005): 791-800

- ^ "Expedition Cruises Fathom Expeditions Custom Cruise". Retrieved 2 March 2016.

- ^ "All About Antarctica". Retrieved 2 March 2016.

- ^ "The Left Coaster: freeze frame". Retrieved 2 March 2016.

- ^ "Ui-te-Rangiora". Encyclopedia Britannica. Retrieved 2 March 2016.

- ^ Sharp 1963, p. 16.

- ^ Druett, Joan (1987). Tupaia – The Remarkable Story of Captain Cook’s Polynesian Navigator. Random House, New Zealand. pp. 226–227.

{{cite book}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|chapterurl=(help) - ^ Druett, Joan (1987). Tupaia – The Remarkable Story of Captain Cook’s Polynesian Navigator. Random House, New Zealand. pp. 218–233.

{{cite book}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|chapterurl=(help) - ^ Sharp 1963.

- ^ Lewis 1976.

- ^ Finney 1963, pp. 6–9.

- ^ See also: Polynesian Voyaging Society, Hokulea.

- ^ a b c d Gatty 1958.

- ^ “Be Your Own Navigator,” Smithsonian Libraries Unbound, Feb. 11, 2016.

- ^ M.D. Halpern (1985) The Origins of the Carolinian Sidereal Compass, Master's thesis, Texas A & M University

- ^ Bellwood, Peter (1987). The Polynesians – Prehistory of an Island People. Thames and Hudson. pp. 39–65.

{{cite book}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|chapterurl=(help) - ^ "Profile: Hekenukumai (Hector) Busby". Toi Māori Aotearoa. Retrieved 12 October 2014.

- ^ "Waka Tapu Canoes". NZMACI & Taitokerau Tarai Waka. Retrieved October 12, 2014.

References

- Lusby et al. (2009/2010)"Navigation and Discovery in the Polynesian Oceanic Empire" Hydrographic Journal Nos.131, 132, 134.

- Finney, Ben R (1963), "New, Non-Armchair Research", in Finney, Ben R (ed.), Pacific Navigation and Voyaging, The Polynesian Society Inc..

- Finney, Ben R, ed. (1976), Pacific Navigation and Voyaging, The Polynesian Society Inc..

- Gatty, Harold (1943), The Raft Book: Lore of Sea and Sky, U.S. Air Force.

- Gatty, Harold (1958), Finding Your Ways Without Map or Compass, Dover Publications, Inc., ISBN 0-486-40613-X.

- Lewis, David (1963), "A Return Voyage Between Puluwat and Saipan Using Micronesian Navigational Techniques", in Finney, Ben R (ed.), Pacific Navigation and Voyaging, The Polynesian Society Inc..

- Lewis, David (1994), We the Navigators:the Ancient art of Landfinding in the Pacific, University of Hawaiʻi Press Inc..

- Kayser, M.; Brauer, S.; Weiss, G.; Underhill, P.A.; Roewer, L.; Schiefenhšfel, W.; Stoneking, M. (2000), Melanesian Origin of Polynesian Y Chromosomes, vol. 10, Current Biology.

- Kayser, M.; Brauer, S.; Weiss, G.; Underhill, P.A.; Roewer, L.; Schiefenhšfel, W.; Stoneking, M. (2000), Melanesian Origin of Polynesian Y Chromosomes, vol. 11, Current Biology.

- Sharp, Andrew (1963), Ancient Voyagers in Polynesia, Longman Paul Ltd..

- Sutton, Douglas G. (Ed.) (1994), The Origins of the First New Zealanders, Auckland University Press.

- King, Michael (2003), History of New Zealand, Penguin Books, ISBN 0-14-301867-1.

- Downes, Lawrence (16 July 2010), Star Man, New York Times.

See also

External links

- Kawaharada, Dennis. "Wayfinding: Modern Methods and Techniques of Non-Instrument Navigation, Based on Pacific Traditions". Wayfinding Strategies and Tactics. Honolulu, HI, USA: Polynesian Voyaging Society. Retrieved 2012-11-26.

- "Wayfinding". Honolulu, HI, USA: Polynesian Voyaging Society. Archived from the original on 2009-09-17. Retrieved November 26, 2012.

- Exploratorium. "Never Lost | Polynesian Navigation" (Flash). San Francisco, CA, USA: Exploratorium. Retrieved November 26, 2012.

{{cite web}}: External link in|publisher=