Sigmund Freud: Difference between revisions

ClueBot NG (talk | contribs) m Reverting possible vandalism by 88.5.243.62 to version by Polisher of Cobwebs. False positive? Report it. Thanks, ClueBot NG. (812818) (Bot) |

Tag: repeating characters |

||

| Line 95: | Line 95: | ||

In February 1923, Freud detected a leukoplakia, a benign growth associated with heavy smoking, on his mouth. Freud initially kept this secret, but in April 1923 he informed Ernest Jones, telling him that the growth had been removed. Freud consulted the [[dermatologist]] Maximilian Steiner, who advised him to quit smoking but lied about the growth's seriousness, minimizing its importance. Freud later saw [[Felix Deutsch]], who saw that the growth was cancerous; he identified it to Freud using the euphemism "a bad leukoplakia" instead of the technical diagnosis [[epithelioma]]. Deutsch advised Freud to stop smoking and have the growth excised. Freud was treated by Marcus Hajek, a [[rhinologist]] whose competence he had previously questioned. Hajek performed an unnecessary cosmetic surgery in his clinic's outpatient department. Freud bled during and after the operation, and may narrowly have escaped death. Freud subsequently saw Deutsch again. Deutsch saw that further surgery would be required, but refrained from telling Freud that he had cancer because he was worried that Freud might wish to commit suicide.<ref>Gay, Peter. ''Freud: A Life for Our Time''. London: Papermac, 1988, pp. 419–420</ref> |

In February 1923, Freud detected a leukoplakia, a benign growth associated with heavy smoking, on his mouth. Freud initially kept this secret, but in April 1923 he informed Ernest Jones, telling him that the growth had been removed. Freud consulted the [[dermatologist]] Maximilian Steiner, who advised him to quit smoking but lied about the growth's seriousness, minimizing its importance. Freud later saw [[Felix Deutsch]], who saw that the growth was cancerous; he identified it to Freud using the euphemism "a bad leukoplakia" instead of the technical diagnosis [[epithelioma]]. Deutsch advised Freud to stop smoking and have the growth excised. Freud was treated by Marcus Hajek, a [[rhinologist]] whose competence he had previously questioned. Hajek performed an unnecessary cosmetic surgery in his clinic's outpatient department. Freud bled during and after the operation, and may narrowly have escaped death. Freud subsequently saw Deutsch again. Deutsch saw that further surgery would be required, but refrained from telling Freud that he had cancer because he was worried that Freud might wish to commit suicide.<ref>Gay, Peter. ''Freud: A Life for Our Time''. London: Papermac, 1988, pp. 419–420</ref> |

||

==Escape from Nazism== |

==Escape from Nazism==??????????????? |

||

In 1930, Freud was awarded the [[Goethe Prize]] in recognition of his contributions to psychology and to German literary culture. In January 1933, the [[Nazis]] took control of Germany, and Freud's books were prominent among those they burned and destroyed. Freud quipped: “What progress we are making. In the [[Middle Ages]] they would have burned me. Now, they are content with burning my books.”<ref>{{cite web|url=http://quotationsbook.com/quote/34000/ |title=Freud, Sigmund, quote: What progress |publisher=Quotationsbook.com |date=23 September 1939 |accessdate=6 February 2011}}</ref> |

In 1930, Freud was awarded the [[Goethe Prize]] in recognition of his contributions to psychology and to German literary culture. In January 1933, the [[Nazis]] took control of Germany, and Freud's books were prominent among those they burned and destroyed. Freud quipped: “What progress we are making. In the [[Middle Ages]] they would have burned me. Now, they are content with burning my books.”<ref>{{cite web|url=http://quotationsbook.com/quote/34000/ |title=Freud, Sigmund, quote: What progress |publisher=Quotationsbook.com |date=23 September 1939 |accessdate=6 February 2011}}</ref> |

||

Revision as of 15:05, 13 January 2012

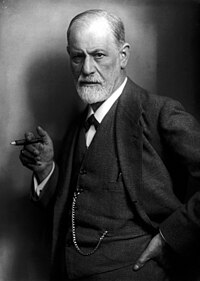

Sigmund Freud | |

|---|---|

Sigmund Freud, by Max Halberstadt, 1921 | |

| Born | 6 May 1856 |

| Died | 23 September 1939 (aged 83) London, England, UK |

| Nationality | Austrian |

| Alma mater | University of Vienna |

| Known for | Psychoanalysis |

| Awards | Goethe Prize Foreign Member of the Royal Society (London)[1] |

| Scientific career | |

| Fields | Neurology Psychotherapy Psychoanalysis |

| Institutions | University of Vienna |

| Signature | |

| Part of a series of articles on |

| Psychoanalysis |

|---|

|

Sigmund Freud (German pronunciation: [ˈziːkmʊnt ˈfʁɔʏt]), born Sigismund Schlomo Freud (6 May 1856 – 23 September 1939), was an Austrian neurologist who founded the discipline of psychoanalysis. Freud's family and ancestry were Jewish, and Freud always considered himself a Jew, although he rejected Judaism and had a critical view of religion. Interested in philosophy as a student, Freud later turned away from it and became a neurological researcher into cerebral palsy, aphasia and microscopic neuroanatomy. Freud went on to develop theories about the unconscious mind and the mechanism of repression, and established the field of verbal psychotherapy by creating psychoanalysis, a clinical method for treating psychopathology through dialogue between a patient (referred to as an "analysand") and a psychoanalyst. Though psychoanalysis has declined as a therapeutic practice, it has helped inspire the development of many other forms of psychotherapy, some diverging from Freud's original ideas and approach.

Freud postulated the existence of libido (an energy with which mental process and structures are invested), developed therapeutic techniques such as the use of free association (in which patients report their thoughts without reservation and make no attempt to concentrate while doing so), discovered the transference (the process by which patients displace on to their analysts feelings based on their experience of earlier figures in their lives) and established its central role in the analytic process, and proposed that dreams help to preserve sleep by representing as fulfilled wishes that would otherwise awake the dreamer. He was also a prolific essayist, drawing on psychoanalysis to contribute to the history, interpretation and critique of culture. Freud's theories have been criticized as pseudo-scientific and sexist, and they have been marginalized within psychology departments, although they remain influential within the humanities. Freud has been called one of the three masters of the "school of suspicion", alongside Karl Marx and Friedrich Nietzsche, while his ideas have been compared to those of Plato and Thomas Aquinas.

Early life

Sigismund Schlomo Freud was born on 6 May 1856, to Jewish Galician parents in the Moravian town of Příbor (Template:Lang-de), Austrian Empire, now part of the Czech Republic.[2] His father, Jacob Freud (1815–1896),[3] was 41, a wool merchant, and had two children by a previous marriage. His mother, Amalié (née Nathansohn), the third wife of Jacob, was 21.[4] He was the first of their eight children and, in accordance with tradition, his parents favored him over his siblings from the early stages of his childhood. Freud was born with a caul, which the family accepted as a positive omen.[5] Freud was raised by the traditions and beliefs of a Jewish religion; although his attitude towards his religion was "critically negative," he always considered himself a Jew.[6]

Despite their poverty, Freud's parents ensured his schooling and education. Due to the Panic of 1857, Freud's father lost his business, and the Freud family moved to Leipzig before settling in Vienna. In 1865, the nine-year-old student Freud entered the Leopoldstädter Kommunal-Realgymnasium, a prominent high school. He proved an outstanding pupil and graduated from the Matura in 1873 with honors. Freud loved literature and was proficient in German, French, Italian, Spanish, English, Hebrew, Latin and Greek.[6] He went to the University of Vienna at 17. Freud had planned to study law, but instead joined the medical faculty at the University of Vienna to study under Darwinist Professor Karl Claus.[7] At that time, the eel life cycle was unknown and Freud spent four weeks at the Austrian zoological research station in Trieste, dissecting hundreds of eels in an unsuccessful search for their male reproductive organs.

Freud greatly admired the philosopher Franz Brentano, known for his theory of perception, as well as Theodor Lipps, who was one of the main supporters of the ideas of the unconscious and empathy.[8] Brentano discussed the possible existence of the unconscious mind in his 1874 book Psychology from an Empirical Standpoint. Although Brentano himself rejected the unconscious, his discussion of it probably helped introduce Freud to the concept.[9]

Freud read Friedrich Nietzsche as a student, and bought his collected works in 1900, the year of Nietzsche's death; Freud told Wilhelm Fliess that he hoped to find in Nietzsche "the words for much that remains mute in me." Peter Gay writes that Freud treated Nietzsche's writings "as texts to be resisted far more than to be studied"; immediately after reporting to Fliess that he had bought Nietzsche's works, Freud added that he had not yet opened them.[10] Students of Freud began to point out analogies between his work and that of Nietzsche almost as soon as he developed a following.[11] After his early interest in it, Freud turned against philosophy and directed his attention away from metaphysical issues.[12]

Freud began smoking tobacco at age 24; initially a cigarette smoker, he became a cigar smoker. Freud believed that smoking enhanced his capacity to work, and believed he could exercise self-discipline in moderating his tobacco-smoking; yet, despite health warnings from Fliess, and to the detriment of his health, Freud remained a smoker, eventually suffering a buccal cancer.[13]

Carl Jung initiated the rumor that a romantic relationship may have developed between Freud and his sister-in-law, Minna Bernays, who had moved into Freud's apartment at 19 Berggasse in 1896.[14] Hans Eysenck suggests that the affair occurred, resulting in an aborted pregnancy for Miss Bernays.[15] The publication in 2006 of a Swiss hotel log, dated 13 August 1898, has been regarded by some Freudian scholars (including Gay) as showing that there was a factual basis to these rumors.[16]

Development of psychoanalysis

In October 1885, Freud went to Paris on a fellowship to study with Jean-Martin Charcot, a renowned neurologist and researcher of hypnosis. He was later to remember the experience of this stay as catalytic in turning him toward the practice of medical psychopathology and away from a less financially promising career in neurology research.[18] Charcot specialized in the study of hysteria and susceptibility to hypnosis, which he frequently demonstrated with patients on stage in front of an audience. Freud later turned away from hypnosis as a potential cure for mental illness, instead favouring free association and dream analysis.[19]

After opening his own medical practice, specializing in neurology, Freud married Martha Bernays in 1886. Her father Berman was the son of Isaac Bernays, chief rabbi in Hamburg. The couple had six children (Mathilde, 1887; Jean-Martin, 1889; Oliver, 1891; Ernst, 1892; Sophie, 1893; Anna, 1895).

After experimenting with hypnosis on his neurotic patients, Freud abandoned it as ineffective. He instead adopted a form of treatment where the patient talked through his or her problems. This came to be known as the "talking cure" and its goal was to locate and release powerful emotional energy that had initially been rejected or imprisoned in the unconscious mind. Freud called this psychic action repression, and he believed it impeded the normal functioning of the psyche, and could even cause physical retardation, which he described as "psychosomatic". The term "talking cure" was initially coined by a patient, Anna O., who was treated by Freud's colleague Josef Breuer. The "talking cure" is widely seen as the basis of psychoanalysis.[20] In late 1895 Freud arrived at the view that unconscious memories of sexual molestation in early childhood were a necessary precondition for the psychoneuroses (hysteria and obsessional neurosis), now known as the seduction theory.[21][22] However he later lost faith in the theory and that led in 1897 to the emergence of Freud's new theory of infantile sexuality, and eventually to the Oedipus complex.[23]

After the publication of The Interpretation of Dreams in November 1899,[24] interest in his theories began to grow, and a circle of supporters developed. However, Freud often clashed with those supporters who criticized his theories, the most famous of whom was Jung. Part of the disagreement between them was due to Jung's interest in and commitment to spirituality and occultism, which Freud saw as unscientific.[25]

Karen Horney, a pupil of Karl Abraham, criticized Freud's theory of femininity, leading him to defend it against her. Horney's challenge to Freud's theories, along with that of Melanie Klein, produced the first psychoanalytic debate on femininity. Ernest Jones, although usually an "ultra-orthodox" Freudian, sided with Horney and Klein. Horney was Freud's most outspoken critic, although her and Jones's disagreement with Freud was over how to interpret penis envy rather than whether it existed. Horney understood Freud's conception of the castration complex as a theory about the biological nature of women, one in which women were biologically castrated men, and rejected it as scientifically unsatisfying.[26]

In his forties, Freud experienced several, probably psychosomatic, medical problems, including depression and heart irregularities that fuelled a superstitious belief that he would die at the age of 51.[27] Around this time Freud began exploring his own dreams, memories, and the dynamics of his personality development. During this self-analysis, he came to realize a hostility he felt towards his father, Jacob Freud, who had died in 1896. He also became convinced that he had developed sexual feelings towards his mother in infancy ("between two and two and a half years").[28] Richard Webster argues that Freud’s account of his self-analysis shows that he “had remembered only a long train journey, from whose duration he deduced that he might have seen his mother undressing”, and that Freud’s memory was an artificial reconstruction.[29]

Patients

Freud used pseudonyms in his case histories. Some patients known by pseudonyms were Cäcilie M. (Anna von Lieben); Dora (Ida Bauer, 1882–1945); Frau Emmy von N. (Fanny Moser); Fräulein Elisabeth von R. (Ilona Weiss);[30] Fräulein Katharina (Aurelia Kronich); Fräulein Lucy R.; Little Hans (Herbert Graf, 1903–1973); Rat Man (Ernst Lanzer, 1878–1914); Enos Fingy (Joshua Wild, 1878–1920);[31] and Wolf Man (Sergei Pankejeff, 1887–1979). Other famous patients included H.D. (1886–1961); Emma Eckstein (1865–1924); Gustav Mahler (1860–1911), with whom Freud had only a single, extended consultation; and Princess Marie Bonaparte.

Several writers have criticized both Freud's clinical efforts and his accounts of them.[32] Eysenck writes that Freud consistently mis-diagnosed his patients and fraudulently misrepresented case histories.[15] Frederick Crews writes that "...even applying his own indulgent criteria, with no allowance for placebo factors and no systematic followup to check for relapses, Freud was unable to document a single unambiguously efficacious treatment".[33] Mikkel Borch-Jacobsen writes that historians of psychoanalysis have shown "that things did not happen in the way Freud and his authorised biographers told us"; he cites Han Israëls's view that "Freud...was so confident in his first theories that he publicly boasted of therapeutic successes that he had not yet obtained." Freud, in that interpretation, was forced to provide explanations for his abandonment of those theories that concealed his real reason, which was that the therapeutic benefits he expected did not materialise; he knew that his patients were not cured, but "did not hesitate to build grand theories on these non-existent foundations."[34]

Followers

Freud spent most of his life in Vienna. From 1891 until 1938 he and his family lived in an apartment at Berggasse 19 near the Innere Stadt or historical quarter of Vienna. As a docent of the University of Vienna, Freud, since the mid-1880s, had been delivering lectures on his theories to small audiences every Saturday evening at the lecture hall of the university's psychiatric clinic.[35] His work generated a considerable degree of interest from a small group of Viennese physicians. From the autumn of 1902 and shortly after his promotion to the honourific title of außerordentlicher Professor,[36] a small group of followers formed around him, meeting at his apartment every Wednesday afternoon, to discuss issues relating to psychology and neuropathology.[37] This group was called the Wednesday Psychological Society (Psychologischen Mittwoch-Gesellschaft) and it marked the beginnings of the worldwide psychoanalytic movement.[38]

This discussion group was founded around Freud at the suggestion of the physician Wilhelm Stekel. Stekel had studied medicine at the University of Vienna under Richard von Krafft-Ebing. His conversion to psychoanalysis is variously attributed to his successful treatment by Freud for a sexual problem or as a result of his reading The Interpretation of Dreams, to which he subsequently gave a positive review in the Viennese daily newspaper Neues Wiener Tagblatt.[39] The other three original members whom Freud invited to attend, Alfred Adler, Max Kahane, and Rudolf Reitler, were also physicians[40] and all five were Jewish by birth.[41] Both Kahane and Reitler were childhood friends of Freud. Kahane had attended the same secondary school and both he and Reitler went to university with Freud. They had kept abreast of Freud's developing ideas through their attendance at his Saturday evening lectures.[42] In 1901, Kahane, who first introduced Stekel to Freud's work,[35] had opened an out-patient psychotherapy institute of which he was the director in Bauernmarkt, in Vienna.[37] In the same year, his medical textbook, Outline of Internal Medicine for Students and Practicing Physicians was published. In it, he provided an outline of Freud's psychoanalytic method.[43] Kahane broke with Freud and left the Wednesday Psychological Society in 1907 for unknown reasons and in 1923 he committed suicide.[44] Reitler was the director of an establishment providing thermal cures in Dorotheergasse which had been founded in 1901.[37] He died prematurely in 1917.[45] Adler, regarded as the most formidable intellect among the early Freud circle, was a socialist who in 1898 had written a health manual for the tailoring trade. He was particularly interested in the potential social impact of psychiatry.[45]

Max Graf, a Viennese musicologist and father of "Little Hans", who had first encountered Freud in 1900 and joined the Wednesday group soon after its initial inception,[46] described the ritual and atmosphere of the early meetings of the society:

The gatherings followed a definite ritual. First one of the members would present a paper. Then, black coffee and cakes were served; cigar and cigarettes were on the table and were consumed in great quantities. After a social quarter of an hour, the discussion would begin. The last and decisive word was always spoken by Freud himself. There was the atmosphere of the foundation of a religion in that room. Freud himself was its new prophet who made the heretofore prevailing methods of psychological investigation appear superficial.[45]

By 1906 the group had grown to sixteen members, including Otto Rank, who was employed as the group's paid secretary.[47] Also in that year Freud began correspondence with Jung who was then an assistant to Eugen Bleuler at the Burghölzli Mental Hospital in Zurich.[48] In March 1907 Jung and Ludwig Binswanger, also a Swiss psychiatrist, travelled to Vienna to visit Freud and attend the discussion group. Thereafter they established a small psychoanalytic group in Zurich. In 1908, reflecting its growing institutional status, the Wednesday group was renamed the Vienna Psychoanalytic Society.[49]

Some of Freud's followers subsequently withdrew from the original psychoanalytic society and founded their own schools.

From 1909, Adler's views on topics such as neurosis began to differ markedly from those held by Freud. As Adler's position appeared increasingly incompatible with Freudianism a series of confrontations between their respective viewpoints took place at the meetings of the Viennese Psychoanalytic Society in January and February 1911. In February 1911 Adler, then the President of the society, resigned his position. At this time Stekel also resigned his position as vice-president of the society. Adler finally left the Freudian group altogether in June 1911 to found his own heretical organisation with nine other members who had also resigned from the group.[50] This new formation was initially called Society for Free Psychoanalysis but it was soon renamed the Society for Individual Psychology. In the period after World War I, Adler became increasingly associated with a psychological position he devised called individual psychology.[51]

In 1912 Jung published Wandlungen und Symbole der Libido (published in English in 1916 as Psychology of the Unconscious) and it became clear that his views were taking a direction quite different from those of Freud. To distinguish his system from psychoanalysis, Jung called it analytical psychology. In the autumn of 1913 the relationship between Freud and Jung broke down irretrievably and the Swiss psychoanalytic organisation fell into disrepair.[52]

Freud published a paper entitled The History of the Psychoanalytic Movement in 1914, the German original being first published in the Jahrbuch der Psychoanalyse, giving his view on the birth and evolution of the psychoanalytic movement and the withdrawal of Adler and Jung from it.

Struggle with cancer

In February 1923, Freud detected a leukoplakia, a benign growth associated with heavy smoking, on his mouth. Freud initially kept this secret, but in April 1923 he informed Ernest Jones, telling him that the growth had been removed. Freud consulted the dermatologist Maximilian Steiner, who advised him to quit smoking but lied about the growth's seriousness, minimizing its importance. Freud later saw Felix Deutsch, who saw that the growth was cancerous; he identified it to Freud using the euphemism "a bad leukoplakia" instead of the technical diagnosis epithelioma. Deutsch advised Freud to stop smoking and have the growth excised. Freud was treated by Marcus Hajek, a rhinologist whose competence he had previously questioned. Hajek performed an unnecessary cosmetic surgery in his clinic's outpatient department. Freud bled during and after the operation, and may narrowly have escaped death. Freud subsequently saw Deutsch again. Deutsch saw that further surgery would be required, but refrained from telling Freud that he had cancer because he was worried that Freud might wish to commit suicide.[53]

==Escape from Nazism==??????????????? In 1930, Freud was awarded the Goethe Prize in recognition of his contributions to psychology and to German literary culture. In January 1933, the Nazis took control of Germany, and Freud's books were prominent among those they burned and destroyed. Freud quipped: “What progress we are making. In the Middle Ages they would have burned me. Now, they are content with burning my books.”[54]

Freud continued to maintain this optimistic underestimate of the growing Nazi threat and remained determined to stay in Vienna, even following the Anschluss of 13 March 1938 in which Nazi Germany annexed Austria, and the violent outbursts of anti-Semitism that ensued.[55]

Ernest Jones, the then President of the International Psychoanalytic Association (IPA), flew into Vienna from London via Prague on 15 March determined to get Freud to change his mind and seek exile in Britain. This prospect and the shock of the arrest and interrogation of Anna Freud by the Gestapo finally convinced Freud it was time to leave Vienna.[56] Jones left for London the following week with a list provided by Freud of the party of émigrés for whom immigration permits would be required. Back in London Jones used his personal acquaintance with the Home Secretary, Sir Samuel Hoare, (they were both members of the same ice-skating club) to expedite the granting of permits. There were seventeen in all and work permits were provided where relevant. Jones also used his influence in scientific circles, persuading the President of the Royal Society, Sir William Bragg, to write to the Foreign Secretary, Lord Halifax, requesting to good effect that diplomatic pressure be applied in Berlin and Vienna on Freud’s behalf. Freud also had support from American diplomats, notably his ex-patient and American ambassador to France, William Bullitt.[57]

The departure from Vienna began in stages throughout April and May 1938. Freud's grandson, Ernst Halberstadt, and Freud’s son Martin’s wife and children left for Paris in April. Freud’s sister-in-law, Minna Bernays, left for London on 5 May, Martin Freud the following week and Freud’s daughter Mathilde and her husband, Robert Hollitscher, on 24 May.[58]

By the end of the month, however, arrangements for Freud’s own departure for London had become stalled, mired in a legally tortuous and financially extortionate process of negotiation with the Nazi authorities. However, the Nazi appointed Kommissar put in charge of his assets and those of the IPA proved to be sympathetic to Freud's plight. Anton Sauerwald had studied chemistry at Vienna University under Professor Josef Herzig, a life-long friend of Freud’s. He evidently retained, notwithstanding his Nazi Party allegiance, a respect for their professional standing. Sauerwald was expected to disclose details of all Freud’s bank accounts to his superiors and follow their instructions to destroy the historic library of books housed in the offices of the IPA. In the event he did neither, removing evidence of Freud’s foreign bank accounts to his own safe-keeping and arranging the storage of the books in the Austrian National Library where they remained until the end of the war.[59]

Though Sauerwald’s intervention lessened the financial burden of the tax on Freud’s declared assets, other substantial charges were levied in relation to the debts of the IPA and the valuable collection of antiquities Freud possessed. Unable to access his own accounts, Freud turned to Princess Marie Bonaparte, the most eminent and wealthy of his French followers, who had arrived in Vienna to offer her support, and it was she who made the necessary funds available.[60] This enabled Sauerwald, who had just received instructions to transform Freud's home into a Race Institute for the study of Aryan superiority, to sign the necessary exit visas and Freud, his wife, Martha, and daughter, Anna, left Vienna on the Orient Express on 4 June, accompanied by their household staff and a doctor. They arrived in Paris the following day where they stayed as guests of Marie Bonaparte and arrived at Victoria Station, London on the 6 June.

Many famous names were soon to call on Freud to pay their respects, notably Salvador Dalí, Stefan Zweig, Leonard and Virginia Woolf and H.G. Wells. Representatives of the Royal Society called with the Society’s Charter for Freud to sign himself into membership. Marie Bonaparte arrived towards the end of June to discuss the fate of Freud’s four elderly sisters left behind in Vienna. Her subsequent attempts to get them exit visas failed and they were all to die in Nazi concentration camps.[61] In the Spring of 1939 Anton Sauerwald arrived to see Freud, ostensibly to discuss matters relating to the assets of the IPA. He was able to do Freud one last favour. He returned to Vienna to drive Freud’s Viennese cancer specialist, Hans Pichler, to London to operate on the worsening condition of Freud’s cancerous jaw.[62]

Sauerwald was tried and imprisoned in 1945 by an Austrian court for his activities as a Nazi Party official. Responding to a plea from his wife, Anna Freud wrote to confirm that Sauerwald “used his office as our appointed commissar in such a manner as to protect my father”. Her intervention helped secure his release from jail in 1947.[63]

In the Freuds new home at 20 Maresfield Garden, Hampstead, North London, Freud’s Vienna consulting room was recreated in faithful detail. He continued to see patients there until the terminal stages of his illness.

Death

In September 1939, Freud, who was suffering from cancer and in severe pain, persuaded his doctor and friend Max Schur to help him commit suicide. After reading Honoré de Balzac's La Peau de chagrin in a single sitting, Freud asked him, “Schur, you remember our ‘contract’ not to leave me in the lurch when the time had come. Now it is nothing but torture and makes no sense.”[64] When Schur replied that he had not forgotten, Freud said, “I thank you.” and then “Talk it over with Anna, and if she thinks it’s right, then make an end of it.”[64] Anna Freud wanted to postpone her father’s death, but Schur convinced her it was pointless to keep him alive, and on 21 and 22 September administered doses of morphine that resulted in Freud's death on 23 September 1939.[64] Three days after his death, Freud's body was cremated at Golders Green Crematorium in England during a service attended by Austrian refugees, including the author Stefan Zweig. His ashes were later placed in the crematorium's columbarium. They rest in an ancient Greek urn that Freud received as a gift from Marie Bonaparte, which he kept in his study in Vienna for many years. After his wife Martha died in 1951, her ashes were also placed in the urn.

Ideas

Early work

Freud began his study of medicine at the University of Vienna in 1873.[66] He took almost nine years to complete his studies, due to his interest in neurophysiological research, specifically investigation of the sexual anatomy of eels and the physiology of the fish nervous system. He entered private practice in neurology for financial reasons, receiving his M.D. degree in 1881 at the age of 25.[67] He was also an early researcher in the field of cerebral palsy, which was then known as "cerebral paralysis." He published several medical papers on the topic, and showed that the disease existed long before other researchers of the period began to notice and study it. He also suggested that William Little, the man who first identified cerebral palsy, was wrong about lack of oxygen during birth being a cause. Instead, he suggested that complications in birth were only a symptom. Freud hoped that his research would provide a solid scientific basis for his therapeutic technique. The goal of Freudian therapy, or psychoanalysis, was to bring repressed thoughts and feelings into consciousness in order to free the patient from suffering repetitive distorted emotions.

Classically, the bringing of unconscious thoughts and feelings to consciousness is brought about by encouraging a patient to talk about dreams and engage in free association, in which patients report their thoughts without reservation and make no attempt to concentrate while doing so.[68] Another important element of psychoanalysis is the transference, the process by which patients displace on to their analysts feelings and ideas which derive from previous figures in their lives. Transference was first seen as a regrettable phenomenon that interfered with the recovery of repressed memories and disturbed patients' objectivity, but by 1912 Freud had come to see it as an essential part of the therapeutic process.[69]

The origin of Freud's early work with psychoanalysis can be linked to Josef Breuer. Freud credited Breuer with opening the way to the discovery of the psychoanalytical method by his treatment of the case of Anna O. In November 1880 Breuer was called in to treat a highly intelligent 21-year-old woman (Bertha Pappenheim) for a persistent cough that he diagnosed as hysterical. He found that while nursing her dying father, she had developed a number of transitory symptoms, including visual disorders and paralysis and contractures of limbs, which he also diagnosed as hysterical. Breuer began to see his patient almost every day as the symptoms increased and became more persistent, and observed that she entered states of absence. He found that when, with his encouragement, she told fantasy stories in her evening states of absence her condition improved, and most of her symptoms had disappeared by April 1881. However, following the death of her father in that month her condition deteriorated again. Breuer recorded that some of the symptoms eventually remitted spontaneously, and that full recovery was achieved by inducing her to recall events that had precipitated the occurrence of a specific symptom.[70][71] In the years immediately following Breuer's treatment, Anna O. spent three short periods in sanatoria with the diagnosis "hysteria" with "somatic symptoms,"[72] and some authors have challenged Breuer's published account of a cure.[73][74][75] Richard Skues rejects this interpretation, which he sees as stemming from both Freudian and anti-psychoanalytical revisionism, that regards both Breuer's narrative of the case as unreliable and his treatment of Anna O. as a failure.[76]

In the early 1890s Freud used a form of treatment based on the one that Breuer had described to him, modified by what he called his "pressure technique" and his newly developed analytic technique of interpretation and reconstruction. According to Freud's later accounts of this period, as a result of his use of this procedure most of his patients in the mid-1890s reported early childhood sexual abuse. He believed these stories, but then came to believe that they were fantasies. He explained these at first as having the function of "fending off" memories of infantile masturbation, but in later years he wrote that they represented Oedipal fantasies.[77]

Another version of events focuses on Freud's proposing that unconscious memories of infantile sexual abuse were at the root of the psychoneuroses in letters to Fliess in October 1895, before he reported that he had actually discovered such abuse among his patients.[78] In the first half of 1896 Freud published three papers stating that he had uncovered, in all of his current patients, deeply repressed memories of sexual abuse in early childhood.[79] In these papers Freud recorded that his patients were not consciously aware of these memories, and must therefore be present as unconscious memories if they were to result in hysterical symptoms or obsessional neurosis. The patients were subjected to considerable pressure to "reproduce" infantile sexual abuse "scenes" that Freud was convinced had been repressed into the unconscious.[80] Patients were generally unconvinced that their experiences of Freud's clinical procedure indicated actual sexual abuse. He reported that even after a supposed "reproduction" of sexual scenes the patients assured him emphatically of their disbelief.[81]

As well as his pressure technique, Freud's clinical procedures involved analytic inference and the symbolic interpretation of symptoms to trace back to memories of infantile sexual abuse.[82] His claim of one hundred percent confirmation of his theory only served to reinforce previously expressed reservations from his colleagues about the validity of findings obtained through his suggestive techniques.[83]

Cocaine

As a medical researcher, Freud was an early user and proponent of cocaine as a stimulant as well as analgesic. He believed that cocaine was a cure for many mental and physical problems, and in his 1884 paper "On Coca" he extolled its virtues. Between 1883 and 1887 he wrote several articles recommending medical applications, including its use as an antidepressant. He narrowly missed out on obtaining scientific priority for discovering its anesthetic properties of which he was aware but had mentioned only in passing.[84] (Karl Koller, a colleague of Freud's in Vienna, received that distinction in 1884 after reporting to a medical society the ways cocaine could be used in delicate eye surgery.) Freud also recommended cocaine as a cure for morphine addiction.[85] He had introduced cocaine to his friend Ernst von Fleischl-Marxow who had become addicted to morphine taken to relieve years of excruciating nerve pain resulting from an infection acquired while performing an autopsy. However, his claim that Fleischl-Marxow was cured of his addiction was premature, though he never acknowledged he had been at fault. Fleischl-Marxow developed an acute case of "cocaine psychosis", and soon returned to using morphine, dying a few years later after more suffering from intolerable pain.[86]

The application as an anesthetic turned out to be one of the few safe uses of cocaine, and as reports of addiction and overdose began to filter in from many places in the world, Freud's medical reputation became somewhat tarnished.[87]

After the "Cocaine Episode"[88] Freud ceased to publicly recommend use of the drug, but continued to take it himself occasionally for depression, migraine and nasal inflammation during the early 1890s, before giving it up in 1896.[89] In this period he came under the influence of his friend and confidant Fliess, who recommended cocaine for the treatment of the so-called nasal reflex neurosis. Fliess, who operated on the noses of several of his own patients, also performed operations on Freud and on one of Freud's patients whom he believed to be suffering from the disorder, Emma Eckstein. However, the surgery proved disastrous.[90]

Some critics [who?] have suggested that much of Freud's early psychoanalytical theory was a by-product of his cocaine use.[91]

The Unconscious

Freud argued for the importance of the unconscious mind in understanding conscious thought and behavior. However, as psychologist Jacques Van Rillaer pointed out, "the unconscious was not discovered by Freud. In 1890, when psychoanalysis was still unheard of, William James, in his monumental treatise on psychology, examined the way Schopenhauer, von Hartmann, Janet, Binet and others had used the term 'unconscious' and 'subconscious'".[92] Moreover, as historian of psychology Mark Altschule observed, "It is difficult—or perhaps impossible—to find a nineteenth-century psychologist or psychiatrist who did not recognize unconscious cerebration as not only real but of the highest importance."[93]

Freud developed his first topology of the psyche in The Interpretation of Dreams (1899) in which he proposed that the unconscious exists and described a method for gaining access to it. The preconscious was described as a layer between conscious and unconscious thought; its contents could be accessed with a little effort. One key factor in the operation of the unconscious is "repression". Freud believed that many people "repress" painful memories deep into their unconscious mind. Although Freud later attempted to find patterns of repression among his patients in order to derive a general model of the mind, he also observed that repression varies among individual patients.

Later, Freud distinguished between three concepts of the unconscious: the descriptive unconscious, the dynamic unconscious, and the system unconscious. The descriptive unconscious referred to all those features of mental life of which people are not subjectively aware. The dynamic unconscious, a more specific construct, referred to mental processes and contents that are defensively removed from consciousness as a result of conflicting attitudes. The system unconscious denoted the idea that when mental processes are repressed, they become organized by principles different from those of the conscious mind, such as condensation and displacement.

Eventually, Freud abandoned the idea of the system unconscious, replacing it with the concept of the id, ego, and super-ego. Throughout his career, however, he retained the descriptive and dynamic conceptions of the unconscious.

Dreams

Freud believed that the function of dreams is to preserve sleep by representing as fulfilled wishes that would otherwise awaken the dreamer.[94]

Psychosexual development

Freud hoped to prove that his model was universally valid and thus turned to ancient mythology and contemporary ethnography for comparative material. Freud named his new theory the Oedipus complex after the famous Greek tragedy Oedipus Rex by Sophocles. "I found in myself a constant love for my mother, and jealousy of my father. I now consider this to be a universal event in childhood," Freud said. Freud sought to anchor this pattern of development in the dynamics of the mind. Each stage is a progression into adult sexual maturity, characterized by a strong ego and the ability to delay gratification (cf. Three Essays on the Theory of Sexuality). He used the Oedipus conflict to point out how much he believed that people desire incest and must repress that desire. The Oedipus conflict was described as a state of psychosexual development and awareness. He also turned to anthropological studies of totemism and argued that totemism reflected a ritualized enactment of a tribal Oedipal conflict.[95] Freud also believed that the Oedipus complex was bisexual, involving an attraction to both parents[96]

Traditional accounts have held that, as a result of frequent reports from his patients, in the mid-1890s Freud posited that psychoneuroses were a consequence of early childhood sexual abuse.[97] More specifically, in three papers published in 1896 he contended that unconscious memories of sexual abuse in infancy are a necessary precondition for the development of adult psychoneuroses. However, examination of Freud's original papers has revealed that his clinical claims were not based on patients' reports but were findings deriving from his analytical clinical methodology, which at that time included coercive procedures.[98][99][100][101][102] He privately expressed his loss of faith in the theory to his friend Fliess in September 1897, giving several reasons, including that he had not been able to bring a single case to a successful conclusion.[103] In 1906, while still maintaining that his earlier claims to have uncovered early childhood sexual abuse events remained valid, he postulated a new theory of the occurrence of unconscious infantile fantasies.[104] He had incorporated his notions of unconscious fantasies in The Interpretation of Dreams (1900), but did not explicitly relate his seduction theory claims to the Oedipus theory until 1925.[105] Notwithstanding his abandonment of the seduction theory, Freud always recognized that some neurotics had experienced childhood sexual abuse.

Freud also believed that the libido developed in individuals by changing its object, a process codified by the concept of sublimation. He argued that humans are born "polymorphously perverse", meaning that any number of objects could be a source of pleasure. He further argued that, as humans develop, they become fixated on different and specific objects through their stages of development—first in the oral stage (exemplified by an infant's pleasure in nursing), then in the anal stage (exemplified by a toddler's pleasure in evacuating his or her bowels), then in the phallic stage. In the latter stage, Freud contended, male infants become fixated on the mother as a sexual object (known as the Oedipus Complex), a phase brought to an end by threats of castration, resulting in the castration complex, the severest trauma in his young life.[106] (In his later writings Freud postulated an equivalent Oedipus situation for infant girls, the sexual fixation being on the father. Though not advocated by Freud himself, the term 'Electra complex' is sometimes used in this context.)[107] The repressive or dormant latency stage of psychosexual development preceded the sexually mature genital stage of psychosexual development. The child needs to receive the proper amount of satisfaction at any given stage in order to move on easily to the next stage of development; under or over gratification can lead to a fixation at that stage, which could cause a regression back to that stage later in life.[108]

Id, ego, and super-ego

In his later work, Freud proposed that the human psyche could be divided into three parts: Id, ego, and super-ego. Freud discussed this model in the 1920 essay Beyond the Pleasure Principle, and fully elaborated upon it in The Ego and the Id (1923), in which he developed it as an alternative to his previous topographic schema (i.e., conscious, unconscious, and preconscious). The id is the completely unconscious, impulsive, child-like portion of the psyche that operates on the "pleasure principle" and is the source of basic impulses and drives; it seeks immediate pleasure and gratification.[108]

Freud acknowledged that his use of the term Id (das Es, "the It") derives from the writings of Georg Groddeck.[109]

The super-ego is the moral component of the psyche, which takes into account no special circumstances in which the morally right thing may not be right for a given situation. The rational ego attempts to exact a balance between the impractical hedonism of the id and the equally impractical moralism of the super-ego; it is the part of the psyche that is usually reflected most directly in a person's actions. When overburdened or threatened by its tasks, it may employ defense mechanisms including denial, repression, and displacement. This concept is usually represented by the "Iceberg Model".[110] This model represents the roles the Id, Ego, and Super Ego play in relation to conscious and unconscious thought.

Freud compared the relationship between the ego and the id to that between a charioteer and his horses: the horses provide the energy and drive, while the charioteer provides direction.[108]

Life and death drives

Freud believed that people are driven by two conflicting central desires: the life drive (libido or Eros) (survival, propagation, hunger, thirst, and sex) and the death drive. The death drive was also termed "Thanatos", although Freud did not use that term; "Thanatos" was introduced in this context by Paul Federn.[111] Freud hypothesized that libido is a form of mental energy with which processes, structures and object-representations are invested.[112]

In Beyond the Pleasure Principle, Freud inferred the existence of the death instinct. Its premise was a regulatory principle that has been described as "the principle of psychic inertia", "the Nirvana principle", and "the conservatism of instinct". Its background was Freud's earlier Project for a Scientific Psychology, where he had defined the principle governing the mental apparatus as its tendency to divest itself of quantity or to reduce tension to zero. Freud had been obliged to abandon that definition, since it proved adequate only to the most rudimentary kinds of mental functioning, and replaced the idea that the apparatus tends toward a level of zero tension with the idea that it tends toward a minimum level of tension.[113]

Freud in effect readopted the original definition in Beyond the Pleasure Principle, this time applying it to a different principle. He asserted that on certain occasions the mind acts as though it could eliminate tension entirely, or in effect to reduce itself to a state of extinction; his key evidence for this was the existence of the compulsion to repeat. Examples of such repetition included the dream life of traumatic neurotics and children's play. In the phenomenon of repetition, Freud saw a psychic trend to work over earlier impressions, to master them and derive pleasure from them, a trend was prior to the pleasure principle but not opposed to it. In addition to that trend, however, there was also a principle at work that was opposed to, and thus "beyond" the pleasure principle. If repetition is a necessary element in the binding of energy or adaptation, when carried to inordinate lengths it becomes a means of abandoning adaptations and reinstating earlier or less evolved psychic positions. By combining this idea with the hypothesis that all repetition is a form of discharge, Freud reached the conclusion that the compulsion to repeat is an effort to restore a state that is both historically primitive and marked by the total draining of energy: death.[113]

Religion

Freud regarded the monotheistic God as an illusion based upon the infantile emotional need for a powerful, supernatural pater familias. He maintained that religion – once necessary to restrain man’s violent nature in the early stages of civilization – in modern times, can be set aside in favor of reason and science.[114] “Obsessive Actions and Religious Practices” (1907) notes the likeness between faith (religious belief) and neurotic obsession.[115] Totem and Taboo (1913) proposes that society and religion begin with the patricide and eating of the powerful paternal figure, who then becomes a revered collective memory.[116] In Civilization and its Discontents (1930), he describes religion as an “oceanic sensation” he never experienced, (despite being a self-identified cultural Jew).[117] Moses and Monotheism (1937) proposes that Moses was the tribal pater familias, killed by the Jews, who psychologically coped with the patricide with a reaction formation conducive to their establishing monotheist Judaism;[118] analogously, he described the Roman Catholic rite of Holy Communion as cultural evidence of the killing and devouring of the sacred father.[119][120] Moreover, he perceived religion, with its suppression of violence, as mediator of the societal and personal, the public and the private, conflicts between Eros and Thanatos, the forces of life and death.[121] Later works indicate Freud’s pessimism about the future of civilization, which he noted in the 1931 edition of Civilization and its Discontents.[122]

Legacy

Psychotherapy

Freud provided the basis for the entire field of individual verbal psychotherapy. According to Donald H. Ford and Hugh B. Urban, "Later systems have differed about therapy and technique in certain respects, but all of them have been constructed around Freud's basic discovery that if one can arrange a special set of conditions and have the patient talk about his difficulties in certain ways, behavior changes of many kinds can be accomplished."[123] For Joel Kovel, "Freud with his methods and central insight remains the progenitor of modern therapy", even though psychoanalysis itself has "sunk to a relatively minor role so far as actual therapeutic practice goes."[124]

The neo-Freudians, a loosely defined group understood by Kovel to include Adler, Rank, Horney, Harry Stack Sullivan and Erich Fromm, rejected Freud's theory of instinctual drive, emphasized 'interpersonal relations' and areas of mental life such as self-assertiveness, and made modifications to therapeutic practice that reflected these theoretical shifts. Adler originated the basic approach, although his influence was indirect. In Kovel's view, the assumption that underlies neo-Freudian practice also informs "most therapeutic approaches now extant" in the United States: "If what is wrong with people follows directly from bad experience, then therapy can be in its basics nothing but good experience as a corrective." Neo-Freudian analysis therefore places more emphasis on the patient's relationship with the analyst and less on exploration of the unconscious.[124]

Jacques Lacan approached psychoanalysis through linguistics and literature. Lacan believed that Freud's essential work had been done prior to 1905, and concerned the interpretation of dreams, neurotic symptoms, and slips, which had been based on a revolutionary way of understanding language and its relation to experience and subjectivity. Lacan believed that ego psychology and object relations theory were based upon misreadings of Freud's work; for Lacan, the determinative dimension of human experience is neither the self (as in ego psychology) nor relations with others (as in object relations theory), but language. Lacan saw desire as more important than need, and considered it necessarily ungratifiable: according to one account, "...for Lacan, the child comes to desire above all else to be the completing object of the m(other's) desire."[125]

Wilhelm Reich developed ideas that Freud had developed at the beginning of his psychoanalytic investigation, but then superseded but never finally discarded; these were the concept of the Actualneurosis, and a theory of anxiety based upon the idea of dammed-up libido. In Freud's original view, what really happened to a person (the 'actual') determined the resulting neurotic disposition. Freud applied that idea both to infants and to adults; in the former case, seductions were sought as the causes of later neuroses, and in the latter incomplete sexual release. Unlike Freud, Reich retained the idea that actual experience, especially sexual experience, was of key significance. Kovel writes that by the 1920s, Reich had "taken Freud's original ideas about sexual release to the point of specifying the orgasm as the criteria of healthy function." Reich was also "developing his ideas about character into a form that would later take shape, first as 'muscular armour', and eventually as a transducer of universal biological energy, the orgone."[124]

Fritz Perls, who helped to develop Gestalt therapy, was influenced by Reich and Jung as well as by Freud. The key idea of gestalt therapy is that Freud overlooked the structure of awareness, which, properly understood, is "an active process that moves toward the construction of organized meaningful wholes...between an organism and its environment." These wholes, called gestalts, are "patterns involving all the layers of organismic function - thought, feeling, and activity." Neurosis is seen as splitting in the formation of gestalts, and anxiety as the organism sensing "the struggle towards its creative unification." Gestalt therapy attempts to cure patients through placing them in contact with "immediate organismic needs." Perls rejected the verbal approach of classical psychoanalysis; talking in gestalt therapy serves the purpose of self-expression rather than gainging self-knowledge. Gestalt therapy usually takes place in groups, and in concentrated "workshops" rather than being spread out over a long period of time; it has been extended into new forms of communal living.[124]

Arthur Janov's primal therapy, which has been an influential post-Freudian psychotherapy, resembles psychoanalytic therapy in its emphasis on early childhood experience, but nevertheless has profound differences with it. While Janov's theory is akin to Freud's early idea of Actualneurosis, he does not have a dynamic psychology but a nature psychology in which need is primary while wish is derivative and dispensable when need is met. Despite its surface similarity to Freud's ideas, Janov's theory lacks a strictly psychological account of the unconscious and belief in infantile sexuality. While for Freud there was a hierarchy of danger situations, for Janov the key event in the child's life is awareness that the parents do not love it.[124] Janov writes that primal therapy in some ways "has returned full circle to early Freud."[126]

Crews considers Freud the key influence upon "champions of survivorship" such as Ellen Bass and Laura Davis, co-authors of The Courage to Heal, although in his view they are indebted not to classic psychoanalysis but to "the pre-psychoanalytic Freud, the one who supposedly took pity on his hysterical patients, found that they were all harboring memories of early abuse...and cured them by unknotting their repression." Crews sees Freud as having anticipated the recovered memory movement's "puritanical alarmism" by emphasizing "mechanical cause-and-effect relations between symptomatology and the premature stimulation of one body zone or another", and with pioneering its "technique of thematically matching a patient's symptom with a sexually symmetrical 'memory.'" Crews believes that Freud's confidence in accurate recall of early memories anticipates the theories of recovered memory therapists such as Lenore Terr, which in his view have lead to people being imprisoned or involved in litigation.[127]

Ethan Watters and Richard Ofshe write that the psychodynamic conception of the mind may be at the end of its usefulness, which could affect "thousands upon thousands and therapists and their patients." They believe that due to "the massive investment the field of psychotherapy has made in the psychodynamic approach, the dying convulsions of the paradigm will not be pretty", although they grant that it is possible that the psychodynamic paradigm "may retain the appearance of buoyancy to the uninformed or unsophisticated."[128]

Science

Verdicts on the scientific merits of Freud's theories have differed. Gilbert Ryle calls Freud "psychology's one man of genius" and the influence of his teaching "deservedly profound" even though its allegories have been "damagingly popular",[129] while David Stafford-Clark calls him "a man whose name will always rank with those of Darwin, Copernicus, Newton, Marx and Einstein; someone who really made a difference to the way the rest of us can begin to think about the meaning of human life and society."[130] Seymour Fisher and Roger P. Greenberg write that, "A reservoir of experimental data pertinent to Freud's work currently exists and...offers support for a respectable number of his major ideas and theories."[131] Camille Paglia writes that Freud, "...intricately explored the metaphors and metamorphoses of the dream process; he demonstrated our daily, comic self-sabotage through slips of the tongue and accidents; he charted the fierce, subliminal conflicts of love and family life; he argued for the full sexuality of women, which the Victorian 19th century censored out; he shockingly established that sexuality does not begin at puberty but in childhood and even infancy".[132]

In contrast, Lydiard H. Horton calls Freud's dream theory "dangerously inaccurate"[133] and Eysenck claims that Freud "set psychiatry back one hundred years" and that "what is true in his theories is not new and what is new in his theories is not true",[134] while Peter Medawar, a Nobel Prize winning immunologist, made the oft-quoted remark that psychoanalysis is the "most stupendous intellectual confidence trick of the twentieth century",[135] and Webster calls psychoanalysis "perhaps the most complex and successful" pseudoscience in history.[136] J. Allan Hobson believes that Freud, by rhetorically discrediting 19th century investigators of dreams such as Alfred Maury and the Marquis de Hervey de Saint-Denis at a time when study of the physiology of the brain was only beginning, created "a break, which lasted half a century, in the scientific tradition of dream theory."[137] Crews writes that "Step by step, we are learning that Freud has been the most overrated figure in the entire history of science and medicine—one who wrought immense harm through the propagation of false etiologies, mistaken diagnoses, and fruitless lines of inquiry."[138]

Karl Popper, who argued that all proper scientific theories must be potentially falsifiable, claimed that Freud's psychoanalytic theories were presented in unfalsifiable form, meaning that no experiment or observation could ever prove them wrong.[139] Adolf Grünbaum considers Popper's critique of Freud flawed, and argues that many of Freud's theories are empirically testable,[140] for example the theory that paranoia results from repressed homosexuality invites the falsifiable prediction that a decline in the repression of homosexuality will result in a corresponding decline in paranoia, thereby disproving Popper's claim that psychoanalytic propositions can never be proven wrong.[141] Grünbaum's view has in turn been challenged from different perspectives. Ernest Gellner describes Freudian psychoanalysis as "an inherently untestable system [that] can and does often permit a kind of ex gratia testing, on the understanding that this privilege remains easily revocable at will and short notice."[142] Frank Cioffi and Allen Esterson both dispute Grünbaum's contentions that Freud was "hospitable to refutation" and his modifications of his theories as a rule "clearly motivated by evidence", arguing that his exegesis of Freud's writings is flawed on this issue.[143][144]

According to a study that appeared in the June 2008 issue of The Journal of the American Psychoanalytic Association, while psychoanalysis remains influential in the humanities, it is regarded as "desiccated and dead" by psychology departments and textbooks. The New York Times commented that to psychoanalysts the report underscores "pressing questions about the relevance of their field and whether it will survive as a practice", noting that the marginalization of Freudian theory in psychology departments has been attributed to psychoanalysts being out of step with the way in which other disciplines in psychology have placed "emphasis on testing the validity of their approaches scientifically." Meanwhile, advances in neuroscience have "attracted new students and resources, further squeezing out psychoanalysis."[145]

Researchers in the emerging field of neuro-psychoanalysis, founded by neuroscientist and psychoanalyst Mark Solms,[146] have argued for Freud's theories, pointing out brain structures relating to Freudian concepts such as libido, drives, the unconscious, and repression.[147][148] However, Solms's case is frequently dependent on the notion of neuro-scientific findings being "broadly consistent" with Freudian theories,[149] rather than strict validations of those theories.[150] More generally the dream researcher G. William Domhoff has disputed claims of specifically Freudian dream theory being validated as contended by Solms.[151] There has also been criticism of the very concept of neuro-psychoanalysis by psychoanalysts.[152]

Philosophy

Freud's theories have influenced the Frankfurt School and critical theory. Herbert Marcuse's Eros and Civilization helped make the idea that Freud and Marx were "speaking to similar questions, if from very different vantage points" credible to the left. Marcuse criticized neo-Freudian revisionism for discarding the death instinct, the primal horde, and the killing of the primal father, which he saw as Freud's most daring hypotheses and possessed of symbolic value, and for flattening out the conflicts between individual and society and between instinctual desires and consciousness, which he saw as a conformist return to pre-Freudian psychology. Rejecting the idea that the death instinct meant an innate urge to aggression, Marcuse interpreted it instead as aiming at the end of the tension that is life. For Marcuse, since it was based on the so-called Nirvana principle, which expressed yearning for the tranquility of inorganic nature, the death instinct was similar in its goals to the life instinct. Marcuse argued that if the tension of life were reduced, the death instinct would cease to be very powerful, thereby turning Freud's seemingly pessimistic conclusions in a utopian direction.[153]

Gellner sees numerous parallels between Plato and Freud: "Plato and Freud hold virtually the same theory of dreams. They hold all in all rather similar tripartite theories of the structure of the human soul/personality." Gellner concludes Freud "constitutes the inversion of Plato: he is Plato stood-on-his-head." Whereas Plato saw an "inherent hierarchy in the very nature of things", and relied upon it to validate norms, Freud was a naturalist who could not follow such an approach. Both men's theories drew a parallel between the structure of the human mind and that of society, but while Plato wanted to strengthen the super-ego, which corresponded to the aristocracy, Freud wanted to strengthen the ego, which corresponded to the middle class.[154] Fromm identifies Freud, together with Karl Marx and Albert Einstein, as the "architects of the modern age", while nevertheless remarking, "That Marx is a figure of world historical significance with whom Freud cannot even be compared in this respect hardly needs to be said."[155] For Paul Robinson, Freud "rendered for the twentieth century services comparable to those Marx rendered for the nineteenth."[156]

Jean-Paul Sartre offers a critique of Freud's theory of the unconscious in Being and Nothingness, based on the claim that consciousness is essentially self-conscious. Sartre also attempts to adapt some of Freud's ideas to his own account of human life, and thereby develop an 'existential psychoanalysis' in which causal categories are replaced by teleological categories.[157] Maurice Merleau-Ponty considers Freud, like Hegel, Kierkegaard, Marx, and Nietzsche, to be one of the anticipators of phenomenology.[158] Theodor W. Adorno writes that Freud was Edmund Husserl's "opposite number...against the entire claim and tendency of whose psychology Husserl's polemic against psychologism could have been directed."[159] Paul Vitz sees numerous similarities between Freud's ideas and Thomism, noting that Brentano saw Thomas Aquinas as one of the first people to teach that there is such a thing as the unconscious and that Freud may have been unknowingly siding with Aquinas on this issue. Vitz adds that to his knowledge, "no one really grounded in both systems has attempted a thorough comparison or synthesis."[9] Paul Ricoeur sees Freud as one of the masters of the "school of suspicion", alongside Marx and Nietzsche.[160] Ricoeur and Jürgen Habermas have helped create "a distinctly hermeneutic version of Freud", one which "claimed him as the most significant progenitor of the shift from an objectifying, empiricist understanding of the human realm to one stressing subjectivity and interpretation." Their interpretation of Freud has been criticized by Grünbaum, who argues that it radically misrepresents Freud's views.[141]

Jacques Derrida finds Freud to be both a late figure in the history of western metaphysics and, with Nietzsche and Heidegger, an important precursor of his own brand of radicalism.[161] Crews criticizes Derrida and his followers for "appropriating and denaturing propositions from systems of thought whose premises they have already rejected", and considers Derrida's use of psychoanalysis one example of such appropriation. Crews writes that Derrida credits Freud with discovering "the irreducibility of the 'effect of deferral'" and the realization that "the present is not primal . . . but reconstitued" in the same essay in which he calls psychoanalysis an "unbelievable mythology." According to Crews, Derrida endorses "Freud's creakiest psychophysical concepts, such as 'repressed memory traces' and 'cathectic innervations', simply because they evoke his own central notion of différance."[162]

Jean-François Lyotard was interested in Freud's view that dream thoughts are hidden messages and codes that require analysis and interpretation, and in Freud's account of the operations of condensation and displacement. Lyotard's theory of the unconscious goes further than Freud's by reversing its account of the dream-work: for Lyotard, condensation (metonymy) does not compact the material of the dream and desire is not disguised. The unconscious is desire, but not in a disguised form at all. It is a force whose intensity is manifest not by way of condensation but via disfiguration.[163]

Bernard Williams writes that there has been hope that some psychoanalytical theories may "support some ethical conception as a necessary part of human happiness", but that in some cases the theories appear to support such hopes because they themselves involve ethical thought. In his view, while such theories may be better as channels of individual help because of their ethical basis, it disqualifies them from providing a basis for ethics.[164]

Feminism

Robinson, observing that "Everyone knows that Freud has fallen from grace", suggests that the disenchantment with Freud can be traced to the revival of feminism.[166] Simone de Beauvoir criticizes Freud and psychoanalysis from an existentialist standpoint in The Second Sex, arguing that Freud saw an "original superiority" in the male that is in reality socially induced.[167] Betty Friedan criticizes Freud and what she considered his Victorian view of women in The Feminine Mystique.[165] Freud's concept of penis envy was attacked by Kate Millett, whose Sexual Politics accused him of confusion and oversights.[168] Naomi Weisstein writes that Freud and his followers erroneously thought that his "years of intensive clinical experience" added up to scientific rigor.[169] Freud is also criticized by Shulamith Firestone and Eva Figes. In The Dialectic of Sex, Firestone argues that Freud was a "poet" who produced metaphors rather than literal truths; in her view, Freud, like feminists, recognized that sexuality was the crucial problem of modern life, but ignored the social context and failed to question society itself. Firestone interprets Freudian "metaphors" in terms of the literal facts of power within the family. Figes tries to place Freud within a "history of ideas." Juliet Mitchell defends Freud against his feminist critics in Psychoanalysis and Feminism, accusing them of misreading him and misunderstanding the implications of psychoanalytic theory for feminism. Mitchell helped introduce English-speaking feminists to Lacan.[167] Mitchell is criticized by Jane Gallop in The Daughter's Seduction. Gallop complements Mitchell for her criticism of "the distortions inflicted by feminists upon Freud's text and his discoveries", but finds her treatment of Lacanian theory lacking.[170]

Some French feminists, among them Julia Kristeva and Luce Irigaray, have been influenced by Freud as interpreted by Lacan.[171] Irigaray has produced a theoretical challenge to Freud and Lacan, using their theories against them to "put forward a coherent psychoanalytic explanation for theoretical bias. She claims that the cultural unconscious only recognizes the male sex, and details the effects of this unconscious belief on accounts of the psychology of women."[172]

Carol Gilligan writes that "The penchant of developmental theorists to project a masculine image, and one that appears frightening to women, goes back at least to Freud..." She sees Freud's criticism of women's sense of justice reappearing in the work of Jean Piaget and Lawrence Kohlberg. Gilligan notes that Nancy Chodorow, in contrast to Freud, attributes differences between the sexes not to anatomy but to the fact that "the early social environment differs for and is experienced differently by male and female children." Chodorow writes "against the masculine bias of psychoanalytic theory" and "replaces Freud's negative and derivative description of female psychology with a positive and direct account of her own."[173]

Works

Major works by Freud

- The Standard Edition of the Complete Psychological Works of Sigmund Freud, translated from the German under the General Editorship of James Strachey. In collaboration with Anna Freud. Assisted by Alix Strachey and Alan Tyson, 24 volumes, Vintage, 1999

- Studies on Hysteria (with Josef Breuer) (Studien über Hysterie, 1895)

- The Complete Letters of Sigmund Freud to Wilhelm Fliess, 1887–1904, Publisher: Belknap Press, 1986, ISBN 978-0-674-15421-6

- The Interpretation of Dreams (Die Traumdeutung, 1899 [1900]) ISBN 978-0-465-01977-9

- The Psychopathology of Everyday Life (Zur Psychopathologie des Alltagslebens, 1901) ISBN 978-1-4565-6856-6

- Three Essays on the Theory of Sexuality (Drei Abhandlungen zur Sexualtheorie, 1905)

- Jokes and their Relation to the Unconscious (Der Witz und seine Beziehung zum Unbewußten, 1905)

- Delusion and Dream in Jensen's Gradiva (Der Wahn und die Träume in W. Jensens Gradiva, 1907)

- Totem and Taboo (Totem und Tabu, 1913)

- On Narcissism (Zur Einführung des Narzißmus, 1914)

- Introduction to Psychoanalysis (Vorlesungen zur Einführung in die Psychoanalyse, 1917)

- Beyond the Pleasure Principle (Jenseits des Lustprinzips, 1920)

- The Ego and the Id (Das Ich und das Es, 1923)

- The Future of an Illusion (Die Zukunft einer Illusion, 1927)

- Civilization and Its Discontents (Das Unbehagen in der Kultur, 1930)

- Moses and Monotheism (Der Mann Moses und die monotheistische Religion, 1939)

- An Outline of Psycho-Analysis (Abriß der Psychoanalyse, 1940)

Correspondence

- The Letters of Sigmund Freud and Otto Rank: Inside Psychoanalysis (eds. E. J. Lieberman and Robert Kramer). Johns Hopkins University Press, 2012. http://www.amazon.com/Letters-Sigmund-Freud-Otto-Rank/dp/1421403544

- The Complete Letters of Sigmund Freud to Wilhelm Fliess, 1887–1904, (editor and translator Jeffrey Moussaieff Masson), 1985, ISBN 978-0-674-15420-9

- The Sigmund Freud Carl Gustav Jung Letters, Publisher: Princeton University Press; Abr edition, 1994, ISBN 978-0-691-03643-4

- The Complete Correspondence of Sigmund Freud and Karl Abraham, 1907–1925, Publisher: Karnac Books, 2002, ISBN 978-1-85575-051-7

- The Complete Correspondence of Sigmund Freud and Ernest Jones, 1908–1939., Belknap Press, Harvard University Press, 1995, ISBN 978-0-674-15424-7

- The Sigmund Freud Ludwig Binswanger Letters, Publisher: Open Gate Press, 2000, ISBN 978-1-871871-45-6

- The Correspondence of Sigmund Freud and Sándor Ferenczi, Volume 1, 1908–1914, Belknap Press, Harvard University Press, 1994, ISBN 978-0-674-17418-4

- The Correspondence of Sigmund Freud and Sándor Ferenczi, Volume 2, 1914–1919, Belknap Press, Harvard University Press, 1996, ISBN 978-0-674-17419-1

- The Correspondence of Sigmund Freud and Sándor Ferenczi, Volume 3, 1920–1933, Belknap Press, Harvard University Press, 2000, ISBN 978-0-674-00297-5

- The Letters of Sigmund Freud to Eduard Silberstein, 1871–1881, Belknap Press, Harvard University Press, ISBN 978-0-674-52828-4

- Sigmund Freud and Lou Andreas-Salome; letters, Publisher: Harcourt Brace Jovanovich; 1972, ISBN 978-0-15-133490-2

- The Letters of Sigmund Freud and Arnold Zweig, Publisher: New York University Press, 1987, ISBN 978-0-8147-2585-6

- Letters of Sigmund Freud – selected and edited by Ernst Ludwig Freud, Publisher: New York: Basic Books, 1960, ISBN 978-0-486-27105-7

Other works and essays

- Dostoevsky and Parricide

- Reflections on War and Death (Zeitgemäßes über Krieg und Tod, 1918)

See also

References

- ^ Attention: This template ({{cite doi}}) is deprecated. To cite the publication identified by doi:10.1098/rsbm.1941.0002, please use {{cite journal}} (if it was published in a bona fide academic journal, otherwise {{cite report}} with

|doi=10.1098/rsbm.1941.0002instead. - ^ Gresser, Moshe. Dual Allegiance: Freud As a Modern Jew. SUNY Press, 1994, p. 225

- ^ Hergenhahn, BR. An introduction to the history of psychology. Thomson Wadsworth, 2005, p. 475

- ^ Gay, Peter. Freud: A Life for Our Time. London: Papermac, 1988, p.5

- ^ Deborah P. Margolis, M.A. "D.P. Morgalis, Freud and his Mother". Pep-web.org. Retrieved 6 February 2011.

- ^ a b Hothersall, D. 2004. "History of Psychology", 4th ed., Mcgraw-Hill:NY p. 276

- ^ Hothersall, D. 1995. History of Psychology, 3rd ed., Mcgraw-Hill:NY

- ^ Pigman, G.W. (1995). "Freud and the history of empathy". The International journal of psycho-analysis. 76 (Pt 2): 237–56. PMID 7628894Template:Inconsistent citations

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: postscript (link) - ^ a b Vitz, Paul C. Sigmund Freud's Christian Unconscious. New York: The Guilford Press, 1988, pp. 53–54.

- ^ Gay, Peter. Freud: A Life for Our Time. London: Papermac, 1988, p.45.

- ^ Paul Roazen, in Dufresne, Todd (ed). Returns of the French Freud: Freud, Lacan, and Beyond. New York and London: Routledge Press, 1997, p. 13

- ^ Holt, Robert. Holt, Robert R.. New York: The Guilford Press, 1989, p. 242

- ^ Gay, Peter. Freud: A Life for Our Time. London: Papermac, 1988, pp. 77, 169.

- ^ Gay, Peter. Freud: A Life for Our Time. London: Papermac, 1988, p. 76.

- ^ a b Eysenck, Hans. Decline and Fall of the Freudian Empire. Transaction Publishers, 2004

- ^ Blumenthal, Ralph (24 December 2006). "Hotel log hints at desire that Freud didn't repress". International Herald TribuneTemplate:Inconsistent citations

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: postscript (link) - ^ "Freudfile Sigmund Freud Life and Work – Jean-Martin Charcot". Freudfile.org. Retrieved 6 February 2011.

- ^ Joseph Aguayo, PhD. "Joseph Aguayo ''Charcot and Freud: Some Implications of Late 19th century French Psychiatry and Politics for the Origins of Psychoanalysis'' (1986). Psychoanalysis and Contemporary Thought, 9:223–260". Pep-web.org. Retrieved 6 February 2011.

- ^ Kennard, Jerry (12 February 2008). AnxietyConnection.com Freud 101: Psychoanalysis

- ^ Gay, Peter. Freud: A Life for Our Time. London: Papermac, 1988, pp. 65–66.

- ^ Freud, Sigmund (1896c). The Aetiology of Hysteria. Standard Edition 3, pp. 203, 211, 219.

- ^ Eissler, K.R. (2005), Freud and the Seduction Theory: A Brief Love Affair. Int. Univ. Press, p. 96.

- ^ R. Webster (1995), Why Freud Was Wrong, HarperCollins, pp. 214–258.

- ^ Peter Gay points out that although Die Traumdietung was published on 4 November 1899, the date that incorrectly appeared on the title page was 1900. Gay, Peter (1998). Freud: a Life for Our Time. New York: Norton. p. 3. ISBN 978-0-393-31826-5.

- ^ Gay, Peter (29 March 1999). "The TIME 100: Sigmund Freud" (Document). Time IncTemplate:Inconsistent citations

{{cite document}}: Unknown parameter|accessdate=ignored (help); Unknown parameter|url=ignored (help)CS1 maint: postscript (link) - ^ Appignanesi, Lisa & Forrester, John. Freud's Women. London: Penguin Books, 2000

- ^ Jones, E. Sigmund Freud: Life and Work. Hogarth Press, 1953, pp. 339–342.

- ^ Masson, Jeffrey M. (ed.). The Complete Letters of Sigmund Freud to Wilhelm Fless, 1887–1904. Harvard University Press, 1985, pp. 268, 272.

- ^ Webster, Richard. Why Freud Was Wrong. London: HarperCollins, 1995, pp. 253–254.

- ^ Appignanesi, Lisa & Forrester, John. Freud's Women. London: Penguin Books, 1992, p.108

- ^ Breger, Louis. Freud: Darkness in the Midst of Vision. Wiley, 2011, p.262