Soyuz 3

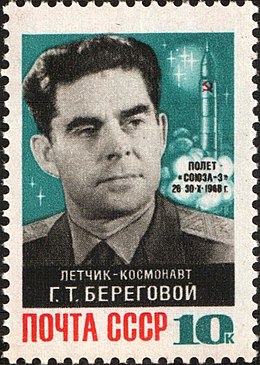

Soyuz 3 commemorative postage stamp, USSR, 1968 | |

| Mission type | Test flight |

|---|---|

| Operator | Soviet space program |

| COSPAR ID | 1968-094A |

| SATCAT no. | 03516 |

| Mission duration | 3 days, 22 hours, 50 minutes, 45 seconds |

| Orbits completed | 81 |

| Spacecraft properties | |

| Spacecraft type | Soyuz 7K-OK |

| Manufacturer | Experimental Design Bureau OKB-1 |

| Launch mass | 6,575 kilograms (14,495 lb) |

| Crew | |

| Crew size | 1 |

| Members | Georgy Beregovoy |

| Callsign | Аргон ([Argon] Error: {{Lang}}: text has italic markup (help) - "Argon") |

| Start of mission | |

| Launch date | 26 October 1968, 08:34:18 UTC |

| Rocket | Soyuz |

| Launch site | Baikonur 31/6[1] |

| End of mission | |

| Landing date | 30 October 1968, 07:25:03 UTC |

| Orbital parameters | |

| Reference system | Geocentric |

| Regime | Low Earth |

| Perigee altitude | 183 kilometres (114 mi) |

| Apogee altitude | 205 kilometres (127 mi) |

| Inclination | 51.7 degrees |

| Period | 88.3 minutes |

| File:Soyuz-3-patch.png

Soyuz programme (Manned missions) | |

Soyuz 3 ("Union 3", Template:Lang-ru) was a spaceflight mission launched by the Soviet Union on 26 October 1968. Flown by Georgy Beregovoy, the Soyuz 7K-OK spacecraft completed 81 orbits over four days. The 47-year-old Beregovoy was a decorated World War II flying ace and the oldest person to go into space up to that time. The mission achieved the first Russian space rendezvous with the unmanned Soyuz 2, but Beregovoy failed to achieve a planned docking of the two craft.

Crew

| Position | Cosmonaut | |

|---|---|---|

| Pilot | Georgy Beregovoy First spaceflight | |

Backup crew

| Position | Cosmonaut | |

|---|---|---|

| Pilot | Vladimir Shatalov | |

Reserve crew

| Position | Cosmonaut | |

|---|---|---|

| Pilot | Boris Volynov | |

Mission parameters

- Mass: 6,575 kg (14,495 lb)

- Perigee: 183 km (114 mi)

- Apogee: 205 km (127 mi)

- Inclination: 51.7°

- Period: 88.3 minutes

Background

The Soviet space program had experienced great success in its early years, but by the mid-1960s the pace of success had slowed. While the Voskhod programme achieved the first multi-crewed spaceflight and first extravehicular activity, problems encountered led to its termination after only two flights, allowing the United States to surpass the Soviet achievements with Project Gemini. The Soyuz programme was intended to rejuvenate the program by developing space rendezvous and docking capability, and practical extravehicular activity without tiring the cosmonaut, as had been demonstrated by the US in Gemini. These capabilities would be required for the Salyut space station program. Soyuz 1 had been launched with the goal of docking with the manned Soyuz 2 craft, but even before the second craft was launched, problems with Soyuz 1 made it clear that Soyuz 2 had to be canceled before the landing of Soyuz 1. This saved the lives of the three-man Soyuz 2 crew; Soyuz 1 ended with the death of cosmonaut Vladimir Komarov on 23 April 1967, due to a faulty parachute system. Soyuz 2 would have flown with the same defective system as Soyuz 1. As a result, the Soyuz spacecraft was revised for Soyuz 2 and Soyuz 3 in 1968.

Spaceflight

Soyuz 2 was launched on 25 October 1968 as an unmanned target vehicle for Soyuz 3, which was launched the following day.[2] The more conservative mission used Beregovoy as the single pilot, with Vladimir Shatalov designated as his backup, and Boris Volynov in reserve. Entering orbit and near Soyuz 2 a half-hour after launch,[3] Beregovoy gradually guided his craft within docking range (200 meters (660 ft)) of his target.[4]

However, Beregovoy failed to achieve docking.[5][6] He failed to notice that Soyuz 2 was turned upside-down in relation to his craft, and used up too much of his maneuvering fuel in the attempt.[7]

He made a second rendezvous and docking attempt the next day, but again failed. Hours later, Soyuz 2 was sent back to Earth and landed by 8:00 am the next day. Beregovoy continued to orbit, making topographical and meteorological observations for the next two days.[8] Beregevoy also treated television viewers to a "live" tour of the spacecraft interior.[9] In addition, the Soviets published a photo of Soyuz 3's launch vehicle on the pad at Baikonur, marking the first time that the R-7 was shown to the outside world.

Return

Beregovoy and Soyuz 3 came back to earth on 30 October 1968, after completing 81 full orbits of the Earth.[10] The re-entry vehicle landed near the city of Karaganda in Kazakhstan, fortuitously cushioned by a blizzard's snowfall.[11] Despite subzero temperatures, Beregovoy's landing was so easy he said later that he hardly felt the impact at all.[12] The Soviets hailed Soyuz 3 as a complete success. Beregovoy was promoted to Major General and named director of the national Center for Cosmonaut Training at Star City.

Soviet secrecy

The launch of Soyuz 2 had not been reported by the Soviet Union, although other nations were aware through their own monitors.[13] It was not until Soyuz 3 was safely aloft that an official announcement was made.

The Soviet government concealed the fact that docking had been unsuccessfully attempted. Contemporary Western news reports described the orbital mission of Soyuz 3 in the same manner as the Soviet press, referring to a "successful rendezvous" with Soyuz 2, but characterizing it as a test with no actual ship-to-ship docking planned.[14] This interpretation was largely accepted for years afterward.[15] The intended docking was disclosed only after the breakup of the Soviet Union, allowing historians to reassess the presumed "success" of the mission.

Legacy

The flight of Soyuz 3 had numerous effects on future space exploration both short- and long-term. The flawless recovery of Soyuz 3 left the spacecraft designers with the impression that re-entry and landing systems had been perfected: the crash-landing of the Zond 6 satellite just one month later had been partly attributed to this mistaken sense of security.[16] The value of the outer space survey of earth was a defining step in the development of the Soyuz program's grand strategy: the later evolution of space-based research platforms have roots in Beregovoy's lengthy and meticulous data-collection.[17] Even the failure of the space docking proved an experiential benefit to the Soviet space program: after the demoralizing catastrophe of Soyuz 1, the credible achievements and safe return of Soyuz 3 breathed new life into the faltering program. New flights continued apace, and they put the knowledge gained from Soyuz 3 towards missions of increasing audacity and success.[18]

References

- ^ Wade, Mark (2016). "Baikonur LC31". Astronautix.com. Encyclopedia Astronautica. Retrieved 14 July 2016.

- ^ Harvey, p .205.

- ^ Harvey, p. 188: "Soyuz 2 was launched first, on October 25, unmanned. Soyuz 3, with Georgi Beregevoi onboard, roared off the pad the next day into a misty drizzling midday sky. Half an hour later he was close to the target, Soyuz 2."

- ^ Clark, p. 49: "The launch announcement said the Soyuz 3 had carried out a rendezvous with the unmanned Soyuz 2 satellite. The two craft were brought to within 200m of each other, with Soyuz 3 being the active partner."

- ^ Hall & Shayler, p. 145: "...details recently received make it clear that docking was planned...."

- ^ Hall & Shayler, p. 145: "...and that Beregevoi had failed to achieve it."

- ^ Hall & Shayler, p. 145: "He [Beregovoy] did not turn his attention to the fact that the ship to which he was meant to dock [Soyuz 2] was overturned [upside-down in relation to his own Soyuz 3].... Therefore the approach of Soyuz 3 [caused] the pilotless object to turn away. In these erroneous manouvres, Beregevoy consumed all the fuel intended for the ship docking."

- ^ Clark, p. 50: "During 28 October, Beregevoi undertook a series of Earth observations, noting three regions of forest fires and a thunderstorm building up in the equatorial regions."

- ^ Clark, p. 50: "Beregevoi took the opportunity of giving viewers a conducted tour around the interior of Soyuz. They were shown both the orbital and descent modules (of course, the rear instrument module could not be seen)...."

- ^ Hall & Shayler, p. 146: "Beregevoi, in Soyuz 3, remained aloft for two more days, and accomplished a safe landing after the eighty-first orbit."

- ^ Hall & Shayler, p. 147: "A blizzard had passed through the landing area earlier that day, and... he descended into a soft snow drift near the city of Karaganda,"

- ^ Harvey, p. 188: "Thick, early snow lay on the ground and the temperature was -12 degrees Celsius.... The impact was so gentle that Georgi Beregevoy barely noticed it."

- ^ Clark, p. 49: "On 25 October... Western tracking stations picked up the launch of a new Soviet satellite. No Soviet announcement was immediately made, however.... News of the launch of Soyuz 2 on the previous day was only revealed in the Soyuz 3 launch announcement...."

- ^ LIFE (11 August 1969), p. 59: "Georgi Beregevoi twice rendezvoused with an unmanned Soviet capsule which had preceded him into space. But he made no attempt to dock with it."

- ^ Gatland, p. 256: "Early tests are related to Georgy Beregevoi's October 1968 flight in Soyuz when the objective was to 'seek out the pilotless Soyuz 2 vehicle orbited earlier, approach it within docking distance and manoeuvre with the use of automatic and manual control systems.".

- ^ Harvey, p. 190: "The [Zond 6] landing accident was so serious that more work was still required on the landing systems, which had been considered solved by the smooth return of Soyuz 3."

- ^ Hall & Shayler, p. 146: "[Beregovoy's survey] was path-finding information for extending the use of Soyuz as an observation and research platform in addition to its role in lunar flights and possibly for its involvement in manned space station operations."

- ^ Clark, p. 50: "With Soyuz 3, the Soviet manned programme regained its confidence, and its success may have encouraged the Soviets to consider a manned flight around the Moon in December, 1968.... Overall it represented a successful return to manned space missions after a break of eighteen months."

Sources

- Clark, Philip (1988). The Soviet Manned Space Program. New York: Orion/Crown. ISBN 9780517569542.

- Gatland, Kenneth (29 April 1971). "Russian space programme plods ahead". New Scientist. 50 (749): 256–257. Retrieved 14 July 2016.

- Hall, Rex D.; Shayler, David J. (2003). Soyuz: A Universal Spacecraft. Berlin: Springer/Praxis. ISBN 9781852336578.

- Harvey, Brian (2007). Soviet and Russian Lunar Exploration. Berlin: Springer/Praxis. ISBN 9780387739762.

- Staff writers (11 August 1969). "A Calendar of Spaceflight: Man's Countdown for the Moon". LIFE. Time, Inc. Retrieved 14 July 2016.