Cable Building (New York City)

| Cable Building | |

|---|---|

The Cable Building from the south (2011) | |

| Location | 611 Broadway, New York, New York |

| Coordinates | 40°43′33″N 73°59′49″W / 40.72583°N 73.99694°W |

| Built | 1892–1894 |

| Architect | Stanford White; McKim, Mead & White |

| Architectural style(s) | Beaux-Arts |

| Designated | June 29, 1999 |

| Part of | NoHo Historic District |

The Cable Building is located at 611 Broadway at the northwest corner with Houston Street in NoHo and Greenwich Village, in Manhattan, New York City. Since it spans a block, the Cable Building also has addresses of 2–18 West Houston Street and 178–188 Mercer Street.

Construction and design

[edit]

The Cable Building was built in 1892–1894 to designs by Stanford White. It is a steel and iron frame structure with brick, stone, and terra-cotta facing. It has a limestone base with a two-story arcade featuring show windows graced by iron spandrels and elegant keystones. Furthermore, it also has a prominent copper cornice with lions' faces, egg-and-dart moldings, and surmounting acanthus.[1] By May 1892, work was underway, though no contract had been awarded for the superstructure.[2] When it was completed, the Real Estate Record and Builders Guide wrote that the Cable Building was "conspicuous among the modern buildings that are fast imparting a new and grander appearance to Broadway".[3] Of special notice was the Broadway main entrance, which was flanked by two figures measuring 11 feet high; the figures were sculpted by the Scottish-American sculptor J. Massey Rhind.[4]

The Cable Building was designed by Stanford White, a partner in McKim, Mead & White, the preeminent American architectural firm at the turn of the twentieth century. It is a nine-story Beaux-Arts structure, which impressively captures White's design principles of the "American Renaissance". This is the only McKim, Mead & White building in the NoHo Historic District. The building's detailing is similar to two of the firm's earlier designs: the 1887 building at 900 Broadway,[5] and the long-gone 1890 Hotel Imperial at Broadway and 32nd Street. Stanford White was the partner in charge for both of these projects for the family and was a close friend.[6] Of the twenty-nine American cities that built cable traction systems between 1870 and 1900 along with their accompanying cable powerhouses, this is the only powerhouse that was built by an architect of such stature.[7]

The building's lot originally contained St Thomas church and cemetery, the church burned in 1851, was rebuilt, and subsequently sold and demolished to build the Cable Building.

St Thomas decided to utilize open ground behind the church for burial vaults. Here they built 58 vaults, each 9×11 feet, that were sold for $250 each. At least 36 of the vaults were purchased by families of St. Thomas. Among those who acquired a family vault was William Backhouse Astor, a member of St. Thomas’ original vestry. William B. Astor’s father John Jacob Astor, the wealthiest man in the country at that time, was interred in William’s private vault in St. Thomas’ churchyard when he died in 1848.

Removal of the burial vaults in the churchyard posed a difficulty in the sale of St. Thomas’ church property at Broadway and Houston. When the vestry originally sold the vault lots at the rear of the church, the deeds protected the rights of the vault owners for the duration of the church’s corporation. [8]

Tenant

[edit]

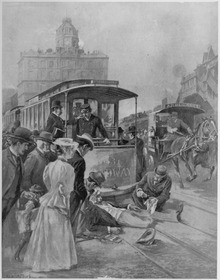

The Cable Building was originally the headquarters and power station for the Metropolitan Traction Company, one of the city's cable car companies, founded in 1892.[9] The MTC's original investment in the building was $750,000. The company spent $12 million on a cable car railway system to move cars on Broadway from Bowling Green to 36th Street, which started operations in 1893. This was the central power station; other stations were at 51st Street and Front Street.[10]

The building's basement, which had been excavated 46' under the street surface, housed four 32-foot winding wheels that carried the cables that pulled the cable streetcars. They were powered by four Corliss steam engines 38" x 60", 1200 HP each, developed by the Dickson Manufacturing Company of Scranton, Pennsylvania.

There were 18 high pressure coal fired Heine boilers totaling 4,500 HP built in St Louis Missouri which powered the engines, the dynamo and heating. [11]

The upper seven floors contained offices arranged around a large internal court with two rectangular light wells.

Less than ten years after it was finished and occupied, due to numerous mechanical problems with the steel driving cables fraying, slipping off drums and guides, and frayed cables becoming "hung up" on the cable car's grip mechanism, causing run-away cars that couldn't be stopped until someone called the powerhouse via telephone to have them shut the line down- the underground cable traction was replaced by electric cables in 1901, but the building retained its original name.

The last Broadway cable car left the Battery Station at 8:27 PM on May 21, 1901.[12]

Later history

[edit]

The New York Railways Company sold the building in 1925, and it was soon occupied by small businesses and manufacturers. From the 1940s to 1970s, the Cable Building housed mainly garment makers, which was the prevailing use in that area at the time. It was converted back to offices in 1983, with new ground-floor storefronts. M. D. Carlisle Real Estate has owned The Cable Building since 1985.

Pop artist Keith Haring's studio was located at 611 Broadway from 1982 to 1985.[13] According to pop artist Andy Warhol, Haring's rent was $1,000 in 1983.[14]

The basement space that originally contained the cable powerhouse became the Angelika Film Center. They operate a multi-screen theater, which specializes in art house films. It was designed by architect Igor Josza[15] and built by contractor Don Schimenti[16] in 1989. Part of the ground floor and all of the second floor has been occupied since 2002 by a 40,217 square-foot Crate & Barrel store.[17] Offices tenant the other seven floors.

The building is in the NoHo Historic District, which the New York City Landmarks Preservation Commission designated as a historic district in 1999.[18]

References

[edit]- ^ New York City Landmarks Preservation Committee, Pages 95–97. "NOHO HISTORIC DISTRICT Designation Report" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on March 26, 2013. Retrieved March 5, 2014.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) - ^ "The Beginning of the Transformation of Broadway". The Real Estate Record and Builders Guide. May 7, 1892. Archived from the original on March 6, 2014. Retrieved March 6, 2014.

- ^ Gray, Christopher (November 7, 1999). "Streetscapes/The 1893 Cable Building, Broadway and Houston Street; Built for New Technology by McKim, Mead & White". The New York Times. Retrieved March 5, 2014.

- ^ "The Cable Building, Northwest Corner of Broadway and Houston Street" (PDF). V. 52, No.1344, Dec. 16, 1893, page 760. Real Estate Record and Builders Guide. Retrieved March 7, 2014.

- ^ Gray, Christopher (January 15, 2006). "Streetscapes | Broadway and 20th Street Same Parents, No Resemblance". The New York Times. Retrieved March 7, 2014.

- ^ Broderick, Mosette (2010). Triumvirate: McKim, Mead & White: Art, Architecture, Scandal, and Class in America's Gilded Age. New York City: Alfred A. Knopf. ISBN 9780307594273.

- ^ Hilton, George W. (1997). The Cable Car in America, page 129. Stanford, California: Stanford University Press.

- ^ French, Mary (February 27, 2022). "St. Thomas' Churchyard". New York City Cemetery Project. Retrieved August 19, 2024.[better source needed]

- ^ "John D. Crimmins Dies of Pneumonia Financier and Philanthropist expires at his Home after Brief Illness at 73". The New York Times. November 10, 1917.

- ^ "The Broadway Cable Railway". The Street Railway Journal. January 1893.

- ^ 1895 Heine Safety Boiler handbook

- ^ Hilton, George W. (1997). The Cable Car in America, page 310. Stanford, California: Stanford University Press.

- ^ Gruen, John (1991). Keith Haring : the authorized biography. New York : Prentice Hall Press. p. 88. ISBN 978-0-13-516113-5.

- ^ Warhol, Andy; Hackett, Pat (1989). The Andy Warhol diaries. New York, NY : Warner Books. p. 483. ISBN 978-0-446-51426-2.

- ^ "Igor Josza Architecture".

- ^ "Lynbrook resident Donald Schimenti dies". Lynbrook Herald. November 28, 2012. Retrieved March 25, 2023.

- ^ Pristin, Terry (January 26, 2002). "Crate & Barrel to Open a Store in Lower Manhattan Landmark". The New York Times. Retrieved March 6, 2014.

- ^ New York City Landmarks Preservation Commission. "NoHo Historic District Designation Report" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on March 26, 2013. Retrieved March 5, 2014.

External links

[edit] Media related to Cable Building (Manhattan) at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Cable Building (Manhattan) at Wikimedia Commons

- 1894 establishments in New York (state)

- Beaux-Arts architecture in New York City

- Broadway (Manhattan)

- Cable car railways in the United States

- Cableways on the National Register of Historic Places

- Greenwich Village

- McKim, Mead & White buildings

- New York City Designated Landmarks in Manhattan

- Office buildings completed in 1894

- Office buildings in Manhattan

- Stanford White buildings

- Transportation buildings and structures on the National Register of Historic Places in New York City