The White Man's Burden

"The White Man's Burden: The United States and the Philippine Islands" (1899), by Rudyard Kipling, is a poem about the Philippine–American War (1899–1902), which was published in a McLure's publication.[1]

Originally, Kipling wrote the poem for the Diamond Jubilee celebration of Queen Victoria's reign (1837–1901), but it was exchanged for the poem "Recessional", also by Kipling. Later, he rewrote the poem "The White Man's Burden" to address the American colonization of the Philippine Islands, a Pacific Ocean archipelago conquered from Imperial Spain, in the three-month Spanish–American War (1898); the birth of the American Empire.[2][3]

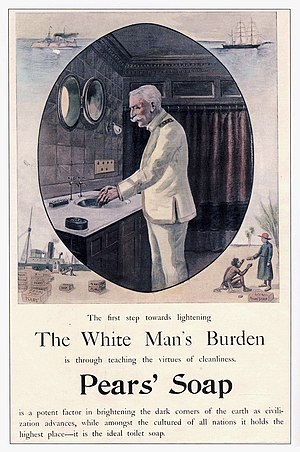

The poem exhorts the reader and the listener to embark upon the enterprise of empire, yet gives somber warning about the costs involved; nonetheless, American imperialists understood the phrase The white man's burden to justify imperialism as a noble enterprise of civilization, conceptually related to the American philosophy of Manifest Destiny.[4][5][6][7]

The title and themes of "The White Man's Burden" ostensibly make the poem about Eurocentric racism and about the belief of the Western world that industrialisation is the way to civilise the Third World.[8][9][10]

History

The poem of "The White Man's Burden" was first published in the 10 February 1899 edition of the New York Sun, a McLure's newspaper.[1]

Three days earlier, on 7 February 1899, to the senate floor, Senator Benjamin Tillman had read aloud three stanzas of "The White Man's Burden" in argument against ratification of the Treaty of Paris , and that the U.S should renounce claim of authority over the Philippine Islands. To that effect, Senator Tillman asked:

Why are we bent on forcing upon them a civilization not suited to them, and which only means, in their view, degradation and a loss of self-respect, which is worse than the loss of life itself?[11]

Four days later, on 11 February 1899, the U.S. Congress ratified the "Treaty of Peace between the United States of America and the Kingdom of Spain" (Treaty of Paris, 1898), which established American imperial jurisdiction upon the archipelago of the Philippine Islands, in the Pacific Ocean, near the Asian mainland.[1]

Poem

The White Man's Burden: The United States and The Philippine Islands (1899)

Take up the White Man's burden, Send forth the best ye breed

Go bind your sons to exile, to serve your captives' need;

To wait in heavy harness, On fluttered folk and wild—

Your new-caught, sullen peoples, Half-devil and half-child.

Take up the White Man's burden, In patience to abide,

To veil the threat of terror And check the show of pride;

By open speech and simple, An hundred times made plain

To seek another's profit, And work another's gain.

Take up the White Man's burden, The savage wars of peace—

Fill full the mouth of Famine And bid the sickness cease;

And when your goal is nearest The end for others sought,

Watch sloth and heathen Folly Bring all your hopes to nought.

Take up the White Man's burden, No tawdry rule of kings,

But toil of serf and sweeper, The tale of common things.

The ports ye shall not enter, The roads ye shall not tread,

Go make them with your living, And mark them with your dead.

Take up the White Man's burden And reap his old reward:

The blame of those ye better, The hate of those ye guard—

The cry of hosts ye humour (Ah, slowly!) toward the light:—

"Why brought he us from bondage, Our loved Egyptian night?"

Take up the White Man's burden, Ye dare not stoop to less—

Nor call too loud on Freedom To cloak your weariness;

By all ye cry or whisper, By all ye leave or do,

The silent, sullen peoples Shall weigh your gods and you.

Take up the White Man's burden, Have done with childish days—

The lightly proffered laurel, The easy, ungrudged praise.

Comes now, to search your manhood, through all the thankless years

Cold, edged with dear-bought wisdom, The judgment of your peers!

The imperialist interpretation of "The White Man's Burden" (1899) proposes that the white man has a moral obligation to rule the non-white peoples of the Earth, whilst encouraging their economic, cultural, and social progress through colonialism. [13]

In the later 20th century, in the context of decolonisation and the Developing World, the phrase "the white man's burden" was emblematic of the "well-intentioned" aspects of Western colonialism and "Eurocentrism".[14] The poem's imperialist interpretation also includes the milder, philanthropic colonialism of the missionaries:

The implication, of course, was that the Empire existed not for the benefit — economic or strategic or otherwise — of Britain, itself, but in order that primitive peoples, incapable of self-government, could, with British guidance, eventually become civilized (and Christianized).[15]

The poem positively represents colonialism as the moral burden of the white race, divinely destined to civilise the brutish and barbarous parts of the world; to wit, the Filipino people are "new-caught, sullen peoples, half-devil and half-child". Although imperialist beliefs were common currency in the culture of that time, there were opponents to Kipling's poetic misrepresentation of imperial conquest and colonisation, notably Mark Twain (To the Person Sitting in Darkness, 1901) and William James, for them "The White Man's Burden" was plain of manner, meaning, and intent.[16]

Kipling offered the poem to Theodore Roosevelt, then governor of New York state (1899–1900), to help him politically persuade anti-imperialist Americans to accept the annexation of the Philippine Islands to the United States.[17][18] Moreover, Kipling's literary work extolling the virtues of British colonialism in India, were popular in the U.S.; thus, in September 1898, Kipling could tell Governor Roosevelt:

Now, go in and put all the weight of your influence into hanging on, permanently, to the whole Philippines. America has gone and stuck a pick-axe into the foundations of a rotten house, and she is morally bound to build the house over, again, from the foundations, or have it fall about her ears.[19]

In the event, the Norton Anthology of English Literature thematically aligns the poem "The White Man's Burden" (1899) with Kipling's beliefs that the British Empire (1583–1945) was the Englishman's "Divine Burden to reign God's Empire on Earth."[3] Moreover, the writer John Derbyshire said that Kipling was "an imperialist utterly without any illusions about what being an imperialist actually means. Which, in some ways, means that he was not really an imperialist at all."[20] Like much of his work, The White Man's Burden (1899) is a poetic celebration of imperialism, which Rudyard Kipling believed eventually would benefit the colonised peoples.[21][22]

Literary responses

In the late 19th century, the philanthropic racism that Rudyard Kipling presented and defended in the poem of The White Man's Burden (1899) provoked contemporary parodies and critical works, such as "The Brown Man's Burden" (1899) by Henry Labouchère, a British politician[23] and "The Black Man's Burden: A Response to Kipling" (April 1899) by H. T. Johnson, a clergyman,[24] and Take up the Black Man's Burden by J. Dallas Bowser.[25] Moreover, a Black Man's Burden Association was organised to demonstrate to the public how the colonial mistreatment of brown people in the Philippines Islands was an extension of the Jim Crow laws (1863–1965) of the legal mistreatment of black Americans at home, in the U.S.[24]

Ernest Crosby wrote a poem, "The Real White Man's Burden" (1902).[26]

In the Congo Free State, the British journalist, E. D. Morel, reported the brutality of Belgian imperialism in "The Black Man's Burden" (1903).[27] In The Black Man's Burden: The White Man in Africa, from the Fifteenth Century to World War I (1920), Morel presents a critique of the relation between the White Man's Burden and the Black Man's Burden.[28][29]

In poem "The Black Man's Burden [A Reply to Rudyard Kipling]" (1920), Hubert Harrison counters the points of colonial-civilization that Kipling extols in "The White Man's Burden" (1899), which result in the moral degradation of colonist and colonized.[30][31]

See also

- The Gods of the Copybook Headings (1919), by Rudyard Kipling

- Industrial Revolution

- 1899 in literature

- 1899 in poetry

- Colonialism

- Rudyard Kipling bibliography

- Orientalism

- White savior narrative in film

Notes

- ^ a b c Herman, Shadowing the White Man's Burden (2010), p. 45.

- ^ Judd, Denis (June 1997). "Diamonds are forever: Kipling's imperialism; poems of Rudyard Kipling". History Today. 47 (6): 37.: "Theodore Roosevelt . . . thought the verses 'rather poor poetry, but good sense from the expansionist stand-point'. Henry Cabot Lodge told Roosevelt, in turn: 'I like it. I think it is better poetry than you say.' "

- ^ a b Stephen Greenblatt (ed.), Norton Anthology of English Literature, New York 2006 ISBN 0-393-92532-3.

- ^ Zwick, Jim (December 16, 2005). Anti-Imperialism in the United States, 1898–1935. [dead link]

- ^ Miller, Stuart Creighton (1982). Benevolent Assimilation: The American Conquest of the Philippines, 1899–1903. Yale University Press. ISBN 0-300-03081-9. p. 5: ". . . imperialist editors came out in favor of retaining the entire archipelago (using) higher-sounding justifications related to the "white man's burden".

- ^ Examples of justification for imperialism based on Kipling's poem include the following (originally published 1899–1902):

- Opinion archive, International Herald Tribune (February 4, 1999). "In Our Pages: 100, 75 and 50 Years Ago; 1899: Kipling's Plea". International Herald Tribune: 6.: "An extraordinary sensation has been created by Mr. Rudyard Kipling's new poem, The White Man's Burden, just published in a New York magazine. It is regarded as the strongest argument yet published in favor of expansion."

- Dixon, Thomas (1902). The Leopard's Spots — A Romance of the White Man's Burden 1865–1900.. Full text of a novel by Thomas Dixon, Jr. praising the Ku Klux Klan, published online by The University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill.

- ^ Pimentel, Benjamin (October 26, 2003). The Philippines; "Liberator" Was Really a Colonizer; Bush's Revisionist History. p. D3.

{{cite book}}:|work=ignored (help): charactising the poem as a "call to imperial conquest". - ^ "Eurocentrism", Encyclopedia of the Developing World, Thomas M. Leonard, Taylor & Francis, eds. 2006, ISBN 0-415-97662-6, p. 636.

- ^ Chisholm, Michael (1982). Modern World Development: A Geographical Perspective. Rowman & Littlefield, 1982, ISBN 0-389-20320-3, p.12.

- ^ Mama, Amina (1995). Beyond the Masks: Race, Gender, and Subjectivity. Routledge, 1995, ISBN 0-415-03544-9, p. 39.

- ^ Herman, Shadowing the White Man's Burden (2010), pp. 41–42.

- ^ Original published version

- ^ The Oxford Companion to English Literature 6th. Ed. (2000) p. 808.

- ^ Plamen Makariev, "Eurocentrism" in: Encyclopedia of the Developing World, Thomas M. Leonard, Taylor & Francis, eds. 2006, ISBN 0-415-97662-6, p. 636: "On one hand, this is the Western 'well-intended' asporation to dominate 'the developing world.' The formula 'the white man's burden' from Rudyard Kipling's eponymous poem is emblematic in this respect". C.f. Chisholm, Michael (1982). Modern World Development: A Geographical Perspective. Rowman & Littlefield, 1982, ISBN 0-389-20320-3, p.12: "This Eurocentric view of the world assumed that, but for the 'improvements' wrought by Europeans in Latin America, in Africa and in Asia, the manifest poverty of their peoples would be even worse."; Rieder, John. Colonialism and the Emergence of Science Fiction 2008. Wesleyan University Press, Middleton, Conn., p. 30: "The protonarrative of progress operates euqally in the ideology of the 'white man's burden' — the belief that non-whites are childlike innocents in need of white men's protection — and the assumptions that undergird Victorian anthropology. From the most legitimate scientific endeavor to the most debased and transparent prejudices runs the common assumption that the relation of the colonizing socieities to the colonized ones is that of the developed, modern present to its own undeveloped, primitive past."

- ^ David Cody, "The growth of the British Empire", VictorianWeb, (Paragraph 4)

- ^ John V. Denson (1999). The Costs of War: America's Pyrrhic Victories. Transaction Publishers. pp. 405–406. ISBN 978-0-7658-0487-7(note ff. 28 & 33).

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: postscript (link) - ^ Wolpert, Stanley (2006)

- ^ Brantlinger, Patrick (2007) "Kipling's 'The White Man's Burden' and its Afterlives" English Literature in Transition 1880–1920, 50.2, pp. 172–191

- ^ Kipling, Rudyard (1990) The Letters of Rudyard Kipling, Thomas Pinney, Editor. London, Macmillan, Vol II, p. 350.

- ^ Sailer, Steve (2001). "What Will Happen In Afghanistan?". United Press International. 26 September 2001.

- ^ Langer, William (1935). A Critique of Imperialism. New York: Council on Foreign Relations, Inc. p. 6.

- ^ Demkin, Stephen (1996). Manifest destiny – Lecture notes. USA: Delaware County Community College.

- ^ Labouchère, Henry (1899). "The Brown Man's Burden" an anti-imperialist parody of Kipling's white-burden poem.

- ^ a b ""The Black Man's Burden": A Response to Kipling". History Matters. American Social History Productions. Retrieved April 12, 2016.

- ^ Brantlinger, Patrick. Taming Cannibals: Race and the Victorians. Cornell University Press, 2011. p215

- ^ Crosby, Ernest (1902). The Real White Man's Burden. Funk and Wagnalls Company. pp. 32–35. Published online by History Matters, American Social History Project, CUNY and George Mason University.

- ^ "The Black Man's Burden"

- ^ "The Black Man's Burden"

- ^ Morel, Edmund (1903). The Black Man's Burden. Fordham University.

- ^ "The Black Man's Burden"

- ^ http://www.expo98.msu.edu/people/Harrison.htm

References

- A Companion to Victorian Poetry, Alison Chapman; Blackwell, Oxford, 2002.

- Chisholm, Michael (1982). Modern World Development: A Geographical Perspective. Rowman & Littlefield, 1982, ISBN 0-389-20320-3.

- Cody, David. The growth of the British Empire. The Victorian Web, University Scholars Program, National University of Singapore, November 2000.

- Crosby, Ernest (1902). The Real White Man's Burden. Funk and Wagnalls Company, 32–35.

- Dixon, Thomas (1902). The Leopard's Spots – A Romance of the White Man's Burden 1865–1900.

- Encyclopedia of India. Ed. Stanley Wolpert. Vol. 3. Detroit: charles Scribner's Sons, 2006, p. 35–36. 4 vols.

- "Eurocentrism". In Encyclopedia of the Developing World. Ed. Thomas M. Leonard, Taylor & Francis, 2006, ISBN 0-415-97662-6.

- Greenblatt, Stephen (ed.). Norton Anthology of English Literature, New York 2006 ISBN 0-393-92532-3

- Kipling. Fordham University. Full text of the poem.

- Labouchère, Henry (1899). "The Brown Man's Burden".

- Mama, Amina (1995). Beyond the Masks: Race, Gender, and Subjectivity. Routledge, 1995, ISBN 0-415-03544-9.

- Miller, Stuart Creighton (1982). Benevolent Assimilation: The American Conquest of the Philippines, 1899–1903. Yale University Press. ISBN 0-300-03081-9.

- Murphy, Gretchen (2010). Shadowing the White Man's Burden: U.S. Imperialism and the Problem of the Color Line. NYU Press. ISBN 978-0-8147-9619-1

- Pimentel, Benjamin (October 26, 2003). "The Philippines; "Liberator" Was Really a Colonizer; Bush's revisionist history". The San Francisco Chronicle: D3.

- Sailer, Steve (2001). "What Will Happen In Afghanistan?". United Press International, 26 September 2001.

- "The White Man's Burden." McClure's Magazine 12 (Feb. 1899).

- The Shining. Jack Nicholson's character Jack, uses the phrase to refer to whiskey.

External links

- The text of the poem at Fordham University

The White Man's Burden public domain audiobook at LibriVox

The White Man's Burden public domain audiobook at LibriVox

- 1899 poems

- White supremacy

- Works about New Imperialism

- Eurocentrism

- Imperialism

- Poetry by Rudyard Kipling

- Racism in the United Kingdom

- British colonisation in Africa

- Philippine–American War

- History of the Philippines (1898–1946)

- 1899 in international relations

- Works originally published in McClure's

- Anti-Filipino sentiment