United Kingdom employment equality law

United Kingdom employment equality law is a body of law which legislates against prejudice-based actions in the workplace. As an integral part of UK labour law it is unlawful to discriminate against a person because they have one of the "protected characteristics", which are, age, disability, gender reassignment, marriage and civil partnership, race, religion or belief, sex, and sexual orientation. The primary legislation is the Equality Act 2010, which outlaws discrimination in access to education, public services, private goods and services or premises in addition to employment. This follows three major European Union Directives, and is supplement by other Acts like the Protection from Harassment Act 1997. Furthermore, discrimination on the grounds of work status, as a part-time worker, fixed term employee, agency worker or union membership is banned as a result of a combination of statutory instruments and the Trade Union and Labour Relations (Consolidation) Act 1992, again following European law. Disputes are typically resolved in the workplace in consultation with an employer or trade union, or with advice from a solicitor, ACAS or the Citizens Advice Bureau a claim may be brought in an employment tribunal. The Equality Act 2006 established the Equality and Human Rights Commission, a body designed to strengthen enforcement of equality laws.[1]

Discrimination is unlawful when an employer is hiring a person, in the terms and conditions of contract that are offered, in making a decision to dismiss a worker, or any other kind of detriment. "Direct discrimination", which means treating a person less favourably than another who lacks the protected characteristic, is always unjustified and unlawful, with the exception of age. It is lawful to discriminate against a person because of their age, however, only if there is a legitimate business justification accepted by a court. Where there is an "occupational requirement" direct discrimination is lawful, so that for instance an employer could refuse to hire a male actor to play a female role in a play, where that is indispensable for the job. "Indirect discrimination" is also unlawful, and this exists when an employer applies a policy to their workplace that affects everyone equally, but it has a disparate impact on a greater proportion of people of one group with a protected characteristic than another, and there is no good business justification for that practice. Disability differs from other protected characteristics in that employers are under a positive duty to make reasonable adjustments to their workplace to accommodate the needs of disabled staff. For age, belief, gender, race and sexuality there is generally no positive obligation to promote equality, and positive discrimination is generally circumscribed by the principle that merit must be regarded as the most important characteristic of a person. In the field of equal pay between men and women, the rules differ in the scope for comparators. Any dismissal because of discrimination is automatically unfair and entitles a person to claim under the Employment Rights Act 1996 section 94 no matter how long they have worked.

History

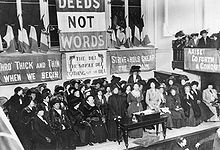

Anti-discrimination law is a recent development. Religious discrimination was first tackled by laws aimed at Roman Catholics. The Papists Act 1778 was the first act that addressed legal discrimination against Roman Catholics, but it was not until the Roman Catholic Relief Act 1829 that Catholics were considered fully emancipated. A year later, in 1830, debates began on the subject of making similar provisions for Jews. A strong Tory lobby in Parliament prevented any furtherance of this cause until the Religious Opinions Act 1846, although this only went some way towards acceptance of all religious viewpoints. It was only the Reform Act 1867 that saw extension of the vote to every male householder. Women were also marginalised from general social participation. The first changes came at municipal level, particular in the Birmingham Municipal Council from the 1830s. The Chartists from the mid 19th century, and the Suffragettes after the turn of the 20th century lobbied for universal suffrage against a conservative judiciary and a liberal political establishment. In Nairn v The University Court of the University of St Andrews (1907), Lord McLaren even proclaimed that it is

"a principle of the unwritten constitutional law of this country that men only were entitled to take part in the election of representatives to Parliament."[2]

The Representation of the People Act 1918 gave the universal franchise to men, and knocked away the last barriers of wealth discrimination for the vote. But for women, only those over 30 were enfranchised, and the judiciary remained as conservative as ever. In Roberts v Hopwood (1925) a metropolitan borough council had decided to pay its workers a minimum of £4 a week, whether they were men or women and regardless of the job they did. The House of Lords approved the district auditor's surcharge for being overly gratuitous, given the fall in the cost of living. Lord Atkinson said

"the council would, in my view, fail in their duty if ... [they] allowed themselves to be guided in preference by some eccentric principles of socialistic philanthropy, or by a feminist ambition to secure the equality of the sexes in the matter of wages in the world of labour."[4]

Though Lord Buckmaster said

"Had they stated that they determined as a borough council to pay the same wage for the same work without regard to the sex or condition of the person who performed it, I should have found it difficult to say that that was not a proper exercise of their discretion."[5]

After a decade, the Representation of the People Act 1928 finally gave women the vote on an equal footing. Attitudes to racial prejudice in the law were set to change markedly with the proverbial "winds of change" sweeping through the Empire after World War II. As Britain's colonies won independence, many immigrated to the motherland, and for the first time communities of all colours were seen in London and the industrial cities of the North. The Equal Pay Act 1970, the Sex Discrimination Act 1975 and the Race Relations Act 1976 were passed by Harold Wilson's Labour government.

In 1975, Britain became a member of the European Community, which became the European Union in 1992 with the agreement of the Maastricht Treaty. The Conservative government opted out of the Social Chapter of the treaty, which included provisions on which anti-discrimination law would be based. Although they passed the Disability Discrimination Act 1995, it was not until Tony Blair's "New Labour" government won the 1997 election that the UK opted into the social provisions of EU law. In 2000, the EU overhauled and introduced new Directives explicitly protecting people with a particular sexuality, religion, belief and age, as well as updating the protection against disability, race and gender discrimination. The law is therefore quite new and is still in a state of flux. Between the EU passing directives and the UK government implementing them, it is apparent that the government has often failed to offer the required minimum level of protection. More changes are likely soon to iron out the anomalies.

Equality framework

Equality legislation in the UK, formerly in separate Acts and regulations for each protected characteristic, is now primarily found in the Equality Act 2010. Particularly since the United Kingdom joined the Social Chapter of the European Union treaties, it mirrors a series of EU Directives. The three main Directives are the Equal Treatment Directive (Directive 2006/54/EC, for gender), the Racial Equality Directive (2000/48/EC) and the Directive establishing a general framework for equal treatment in employment and occupation (2000/78/EC, for religion, belief, sexuality, disability and age). Updates can be implemented automatically in domestic legislation as required by the case law of the European Court of Justice or changes in EU legislation.

Direct discrimination

Direct discrimination occurs when an employer treats someone less favourably on the ground of a protected characteristic. It is unlawful under section 13 of the Equality Act 2010. A protected characteristic (age, disability, gender reassignment, marriage and civil partnership, race, religion or belief, sex, and sexual orientation) must be the reason for the different treatment, so that it is because of that characteristic that the less favourable treatment occurs. Generally, the law protects everyone, not just a group perceived to suffer discrimination. Therefore, it is unlawful to treat a man less favourably than a woman, or a woman less favourably than a man, on the ground of the person's sex. However people who are single are not protected against more favourable treatment of people in marriage or civil partnership, and able people are not protected if a disabled person is treated more favourably.

In Coleman v Attridge Law in the European Court of Justice confirmed that a person may claim discrimination even if they are not the person with the protected characteristic, but rather they suffer unfavourable treatment because of someone they associate with.

For the protected characteristic of Age, it is a defence to a claim of direct discrimination that the discrimination is "justified" by some reason. There is no defence of justification for other protected characteristics.

Harassment

Under the Equality Act 2010 section 26,[6] a person harasses another if he or she engages in unwanted conduct related to a relevant protected characteristic, and the conduct has the purpose or effect of violating the other's dignity, or creating an intimidating, hostile, degrading, humiliating or offensive environment for the other. It is also harassment if a person treats another less favourably because the other has rejected or submitted to unwanted conduct of a sexual nature.

Victimisation

The definition of "victimisation" is found in the Equality Act 2010 section 27.[7] It refers to subjecting a person to a further detriment after they try to complain or bring proceedings in connection with discrimination, on their own behalf or on behalf of someone else.

Indirect discrimination

"Indirect" discrimination is unlawful under the Equality Act 2010 section 19.[8] It involves the application of a provision, criterion or practice to everyone, which has a disproportionate effect on some people and is not objectively justified. For instance, a requirement that applicants for a job be over a certain height would have a greater impact on women than on men, as the average height of women is lower than that of men. It is a defence for the employer to show that the requirement is “a proportionate means of achieving a legitimate aim”.

- Ojutiku v Manpower Services Commission [1982] EWCA Civ 3, [1982] ICR 661

- R (Schaffter) v Secretary of State for Education [1987] IRLR 53

- Rainey v Greater Glasgow Health Board [1987] AC 224

- Clymo v Wandsworth London Borough Council [1989] ICR 250

- Enderby v Frenchay Health Authority (C-127/92) [1994] ICR 112

- R (Equal Opportunities Commission) v Secretary of State for Trade and Industry [1995] 1 AC 1

- Staffordshire County Council v Black [1995] IRLR 234

- R (Seymour Smith) v Secretary of State for Employment [2000] ICR 244

- Rutherford v Secretary of State for Trade and Industry (No 2) [2006] UKHL 19

Positive action

Discrimination law is "blind" in that motive is irrelevant to discrimination and both minorities or majorities could make discrimination claims if they suffer less favourable treatment. Positive discrimination (or "affirmative action" as it is known in the US) to fill up diversity quotas, or for any other purpose, is prohibited throughout Europe, because it violates the principle of equal treatment just as much as negative discrimination. There is, however, a large exception. Suppose an employer is hiring new staff, and they have 2 applications where the applicants are equally qualified for the job. If the workforce does not reflect society's makeup (e.g. that women, or ethnic minorities are under-represented) then the employer may prefer the candidate which would correct that imbalance. But they may only do so where both candidates are of equal merit, and further conditions must be met. This type of measure is also known as positive action. Sections 158 and 159 Equality Act 2010 set out the circumstances in which positive action is allowed. Section 159, which deals with positive action in connection with recruitment and promotion (and which is the basis for the example of equally qualified applicants above), did not come into force until April 2011.[9] The Government Equalities Office has issued a guide to the Section 159 rules.[10] Section 158 deals with the circumstances in which positive action is permitted other than in connection with recruitment and promotion, for example in provision of training opportunities. Section 158 does not have the requirement for candidates to be equally qualified.

Disability claims

The normal types of claim apply to disability, but additional types of claim are particular to it. These are 'discrimination arising from disability' and the reasonable adjustment duty. "Discrimination arising from disability" was a newly formulated test introduced after the House of Lords decision in Lewisham LBC v Malcolm and EHRC[11] was felt to have shifted the balance of protection too far away from disabled people.[12] Section 15 Equality Act 2010 creates a broad protection against being treated unfavourably "because of something arising in consequence of" the person's disability, but subject to the employer having an 'objective justification' defence if it shows its action was a proportionate means of achieving a legitimate aim. There is also a 'knowledge requirement', in that the employer has a defence if it shows it did not know, and could not reasonably be expected to know, that the person had the disability. Section 15 will apply, for example, where a disabled person is dismissed because of a long absence from work which resulted from their disability - the issue will be whether the employer can show the 'objective justification' defence applies (assuming the 'knowledge requirement' is met).

The reasonable adjustment duty is particularly important. The duty can apply where a disabled person is put at a 'substantial' disadvantage in comparison with non-disabled people by a 'provision, criterion or practice' or by a physical feature. The employer's obligation is, broadly, to take such steps as it is reasonable to have to take to avoid the disadvantage (s 20 Equality Act 2010). 'Substantial' means only more than minor or trivial (s 212(1) Equality Act 2010). A further strand of the duty can require an employer to provide an auxiliary aid or service (s 20(5) Equality Act 2010). There are provisions dealing with employer's lack of knowledge of the disability (Equality Act 2010 Sch 8 para 20).

Employers should actively pursue policies to accommodate protected groups into the workforce. This duty is made explicit in law for pregnant women and for people who are disabled. For people with religious sensitivities, particularly the desire to worship during work cases show there is no duty, but employers should apply their minds to accommodating their employee's wishes even if they ultimately decide not to.

Enforcement

The main outcome of the Equality Act 2006 was the establishment of a new Equality and Human Rights Commission, subsuming specialist bodies from before. Its role is in research, promotion, raising awareness and enforcement of equality standards. For lawyers, the most important work of predecessors has been strategic litigation[13] (advising and funding cases which could significantly advance the law) and developing codes of best practice for employers to use. Around 20,000 discrimination cases are brought each year to UK tribunals.

Defences

Occupational Requirement

Under the Equality Act 2010 Sch 9,[14] a number of defences are available to employers who have policies which discriminate. An "occupational requirement" refers to exceptions to the prohibition on direct discrimination. An example could be a theatre requiring an actor of Black African origin to play a Black African character. An employer has the burden of showing that they genuinely need somebody of a particular gender, race, religion, etc., for the job. These exceptions are few.

Material Difference

Under section 23 of the Equality Act, in order to show that there has been discrimination, the claimant must show that there is no material difference between the claimant and the other person, or "comparator", who does not share the same protected characteristic. If the respondent can show that there is another cause for the different treatment, not related to the protected characteristic, then the claim will fail.

Justification

It is a defence to a claim of unlawful indirect discrimination, and also to a claim of direct discrimination on the ground of age, that the discriminatory act is "a proportionate means of achieving a legitimate aim" (sections 13(2) and 19).

Equality protection

People with a protected characteristic are protected from discrimination in employment, and in access to services, education, premises, and associations. Examples of prohibited discrimination include as customers, in social security, access to education and other public services. The UK Labour Government codified and strengthened the disparate heads of protection into a single act, namely the Equality Act 2010.

Sex

In the UK, equality between sexes has been a principle of employment law on since the 1970s, when the Equal Pay Act 1970 and the Sex Discrimination Act 1975 were introduced. Also, in 1972, the UK joined the European Community (now the EU). Article 141(1) of the Treaty of the European Community states,

"Each Member State shall ensure that the principle of equal pay for male and female workers for equal work or work of equal value is applied."

- Directive 2006/54/EC "on the implementation of the principle of equal opportunities and equal treatment of men and women in matters of employment and occupation".

- Equal pay

Race

In the Weaver v NATFHE race discrimination case (also known as the Bournville College Racial Harassment issue), an Industrial Tribunal decided that the trade union NATFHE was entitled to apply its rule that a members' case against another member would not be supported if it put that member's tenure at risk. [1]

- Ghai v Newcastle City Council [2010] EWCA Civ 59

Disability

- Disability Discrimination (Meaning of Disability) Regulations 1996, (SI 1996/1455) esp. rr.3-5

- Guidance on Matters to be Taken into Account in Determining Questions Relating to the Definition of Disability from the Department for Work and Pensions website, esp Part II, para A1; "a substantial effect [under s.1(1) DDA 1995] is one which is more than "minor" or "trivial", and provides that tribunals ought to have regard, in deciding whether an impairment has such an effect to" things like time for relevant activities, the way they are done, impairments' cumulative effects and the effects of behaviour and environment.

- Aylott v Stockton-on-Tees Borough Council [2010] EWCA Civ 910

- Thaine v London School of Economics [2010] ICR 1422

- Clark v TDG Ltd (t/a Novacold Ltd) [1999] IRLR 318

- Leonard v Southern Derbyshire Chamber of Commerce [2001] IRLR 19

Sexuality

- Employment Equality (Sexual Orientation) Regulations 2003 SI 2003/1661 (in effect from 1 December 2003)

- Equality Act (Sexual Orientation) Regulations

Religion or belief

While direct discrimination on grounds of religion or belief is automatically unlawful, the nature of religions or beliefs leads to the conclusion that objective justification for disparate impact is easier. Beliefs often lead adherents to the need to manifest their closely held views, in a way which may conflict with ordinary requirements of the work place. There is not the same degree of privilege granted to beliefs as is to a disability, requiring "reasonable adjustments" for the wishes of the believer. So in cases where an adherent to a religion wishes to take time off to pray, or wear a particular article of clothing or jewellery, it will usually be within the right of the employer to insist that the contract of employment is performed as was initially agreed. This refusal of the law to grant privileged status to beliefs may reflect the element of choice in belief or the need of a secular society to treat all people, whether believers or not, equally.[15]

Discrimination on grounds of religion was previously covered in an ad hoc way for Muslims and Sikhs through the race discrimination provisions. The new regulations were introduced to comply with the EU Framework Directive 2000/78/EC on religion or belief, age, sexuality and disability.

- Article 9 ECHR - Freedom of religion

- Islington LBC v Ladele [2009] EWCA Civ 1357

Age

- Employment Equality (Age) Regulations 2006, SI 2006/1031 (now repealed and replaced by the Equality Act 2010)[16]

- Seldon v Clarkson Wright & Jakes and another [2010] EWCA Civ 899[17]

Work status protection

More recently, two measures have been introduced, and one has been proposed, to prohibit discrimination in employment based on atypical work patterns, for employees who are not considered permanent. The Part-time Workers Regulations and the Fixed-term Employee Regulations were partly introduced to remedy the pay gap between men and women. The reason is, women are far more likely to be doing non-full-time permanent jobs. However following the Treaty of Amsterdam, a new Article 13 promised Community action to remedy inequalities generally. The abortive Agency Workers Directive was meant to be the third pillar in this programme. Discrimination against union members is also a serious problem, for the obvious reason that some employers view unionisation as threat to their right to manage.

Part time workers

- Part-time Workers (Prevention of Less Favourable Treatment) Regulations 2000, SI 2000/1551

- McMenemy v Capital Business Ltd [2007] IRLR 400

- Sharma v Manchester City Council [2008] IRLR 336

- Matthews v Kent & Medway Towns Fire Authority [2006] IRLR 367

- A McColgan, 'Missing the point?' (2000) 29 Industrial Law Journal 260

- O'Brien v Ministry of Justice [2010] UKSC 34

Fixed term "employees"

Agency workers

Union members

- Amalgamated Society of Railway Servants v Osborne [1910] AC 87, Lords Shaw and James said trade union support for MPs was ‘unconstitutional and illegal’. Reversed in 1913.

- Article 11 ECHR

- Public Interest Disclosure Act 1998

- O'Kelly v Trusthouse Forte plc

- Wilson and Palmer v United Kingdom

- Trade Union and Labour Relations (Consolidation) Act 1992 ss 137-177

See also

|

|

Notes

- ^ The EHRC replaced the Commission for Racial Equality, the Equal Opportunities Commission, and the Disability Rights Commission.

- ^ (1907) 15 SLT 471, 473

- ^ Quoted in Bartley, p. 98.

- ^ Roberts v Hopwood [1925] AC 578, 594

- ^ Roberts v Hopwood [1925] AC 578 (HL), at 590

- ^ Formerly the SDA 1975 s 4A, RRA 1976 s 3A, DDA 1995 s 3B, EE(SO)R 2003 r 5, EE(RB)R 2003 r 5, EE(A)R 2006 r 6

- ^ Formerly the SDA 1975 s 4(1), RRA 1976 s 2, DDA 1995 s 55, EE(RB)R 2003 r 4, EE(SO)R 2003 r 4, EE(A)R 2006 r 4

- ^ Formerly SDA 1975 ss 1(1)(b) and 1(2)(b), RRA 1976 ss 1(1)(b) and 1(1A), EE(RB)R 2003 r 3(b), EE(SO)R 2003 r 3(b), EE(A)R 2006 r 3(b)

- ^ "Featherstone: new tools will help make the workplace fairer". Government Equalities Office. Retrieved 16 January 2011.

- ^ "Equality Act 2010: What do I need to know? A quick start guide to using positive action in recruitment and promotion". Government Equalities Office. Retrieved 16 January 2011.

- ^ [2008] UKHL 43, [2008] IRLR 700 overturning Clark v TDG Ltd (t/a Novacold Ltd)

- ^ "Consultation on Improving Protection From Disability Discrimination: Government Response" (PDF). Office for Disability Issues. April 2009. Retrieved 16 January 2011.

- ^ This has been in decline recently; in 2005 the Commission for Racial Equality only funded three cases, CRE, Annual Report 2005 Archived June 9, 2007, at the Wayback Machine (London: CRE, 2006) whereas up to 1984 it was funding one fifth of all claims.

- ^ Formerly SDA 1975 s 7, RRA 1976 ss 4A and 5, EE(RB)R 2003 r 7, EE(SO)R 2003 r 7, EE(A)R 2006 r 8

- ^ K Marx, Zur Kritik der Hegelschen Rechtsphilosophie (Paris 1844) 'Religion ist der Seufzer der bedrängten Kreatur, das Gemüt einer herzlosen Welt, wie sie der Geist geistloser Zuständer ist.' 'Religion is the sigh of a broken being, the heart of a heartless world, just as it is the soul of soulless surroundings.'

- ^ "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 26 March 2011. Retrieved 14 February 2011.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help)CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link) - ^ "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 17 August 2011. Retrieved 8 November 2011.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help)CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

References

- Books

- Hugh Collins, Keith Ewing, Aileen McColgan, Labour Law, Text, Cases and Materials (Hart 2005) ISBN 1-84113-362-0

- Simon Deakin, Gillian Morris, Labour Law (Hart 2004)

- Lord Wedderburn, The Worker and the Law (Sweet and Maxwell 1986) ISBN 0-421-37060-2

- Gary Becker The Economics of Discrimination (2nd edn 1971)

- Richard Posner, 'The Efficiency and Efficacy of Title VII' (Dec 1987) 136(2) University of Pennsylvania Law Review 513-521

- Articles

- C O’Cinneide, “The Commission for Equality and Human Rights: A New Institution for New and Uncertain Times” (2007) Industrial Law Journal 141

External links

- Trade Unions

- Non-permanent workers

- Part-time Work Directive 97/81/EC

- Fixed-term Work Directive 99/70/EC

- Agency Workers Directive 2008/56/EC

- Part-time Workers (Prevention of Less Favourable Treatment) Regulations 2000, SI 2000/1551

- Fixed Term Employees (Prevention of Less Favourable Treatment) Regulations 2002, SI 2002/2034

- Agency Work Regulations 2010, text here

- Protected characteristics

- Treaty of the European Community, whose Article 141 address equal pay between men and women. Article 13, introduced by the Treaty of Amsterdam in 1996, is the basis for

- Framework Directive 2000/78/EC

- Race Equality Directive 2000/43/EC

- Equal Treatment Directive 2006/54/EC, replacing 97/80/EC, 76/207/EEC and 2002/73/EC

- Other websites

- Support for employers - Employers' Forum on Disability

- Disability Standard Benchmark for Employers

- Agediscrimination.info - for age discrimination statistics and information aimed at employers, employees, researchers, students, journalists and others interested in age discrimination issues in the UK.