United States Forces Japan

This article may require copy editing for grammar, style, cohesion, tone, or spelling. (October 2018) |

The article's lead section may need to be rewritten. (October 2018) |

| United States Forces Japan 在日米軍 | |

|---|---|

USFJ | |

| Country | |

| Size | 50,000 (approx.) |

| Headquarters | Yokota Air Base, Fussa, Western Tokyo |

| Nickname(s) | USFJ |

The United States Forces Japan (USFJ) (在日米軍, Zainichi Beigun) is an active subordinate unified command of the United States Indo-Pacific Command (USINDOPACOM). It was activated at Fuchū Air Station, Tokyo, Japan on 1 July 1957 to replace the Far East Command (FEC). USFJ is commanded by the Commander, U.S. Forces, Japan (COMUSJAPAN). COMUSJAPAN is also the Commander, Fifth Air Force. At present, USFJ is headquartered at Yokota Air Base, Tokyo, Japan.

COMUSJAPAN, plans, directs and supervises the execution of missions and responsibilities assigned by the Commander, U.S. Indo-Pacific Command (COMUSINDOPACOM). He establishes and implements policies to accomplish the mission of the United States Armed Forces in Japan. He is responsible for developing plans for the defense of Japan, and he must be prepared if contingencies arise, to assume operational control of assigned and attached U.S. forces for the execution of those plans.

COMUSJAPAN supports the Security Treaty and administers the Status of Forces Agreement (SOFA) between the United States and Japan. He is responsible for coordinating various matters of interest with the service commanders in Japan. These include matters affecting US-Japan relationships among and between Department of Defense (DOD) agencies; DOD agencies and the U.S. Ambassador to Japan; and DOD agencies and the Government of Japan (GOJ).

Under the Treaty of Mutual Cooperation and Security between the United States and Japan, the United States is obliged to protect Japan in close cooperation with the Japan Self-Defense Forces for maritime defense, ballistic missile defense, domestic air control, communications security (COMSEC) and disaster response operations.

History

After the Japanese surrender in the end of World War II in Asia, the United States Armed Forces assumed administrative authority in Japan. The Japanese Imperial Army and Navy were decommissioned, and the U.S. Armed Forces took control of their military bases until the new government could be formed and positioned to reestablish authority. Allied forces planned to demilitarize Japan, and new government adopted the Constitution of Japan with a no-armed-force clause in 1947.

After the Korean War began in 1950, Douglas MacArthur, the Supreme Commander for the Allied Powers in Japan and the Japanese government established the paramilitary "National Police Reserve", which was later developed into the Japan Ground Self-Defense Force (JGSDF).

In 1951, the Treaty of San Francisco was signed by the allied countries and Japan, which restored its formal sovereignty. At the same time, the U.S. and Japan signed the Japan-America Security Alliance. By this treaty, USFJ is responsible for the defense of Japan. As part of this agreement, the Japanese government requested that the U.S. military bases remain in Japan, and agreed to provide funds and various interests specified in the Status of Forces Agreement. At the expiration of the treaty, the United States and Japan signed the new Treaty of Mutual Cooperation and Security between the United States and Japan. The status of the United States Forces Japan was defined in the U.S.–Japan Status of Forces Agreement. This treaty is still in effect, and it forms the basis of Japan's foreign policy.

In the Vietnam War, the US military bases in Japan, especially those in Okinawa Prefecture, were used as important strategic and logistic bases. In 1970, the Koza riot occurred against the US military presence in Okinawa. The USAF strategic bombers were deployed in the bases in Okinawa, which was still administered by the U.S. government. Before the 1972 reversion of the island to Japanese administration, it has been speculated but never confirmed that up to 1,200 nuclear weapons may have been stored at Kadena Air Base, Okinawa in the 1960s.[1]

As of 2013[update], there are approximately 50,000 U.S. military personnel stationed in Japan, along with approximately 40,000 dependents of military personnel and another 5,500 American civilians employed there by the United States Department of Defense. The United States Seventh Fleet is based in Yokosuka, Kanagawa Prefecture. The 3rd Marine Expeditionary Force (III MEF) is based in Okinawa. 130 USAF fighters are stationed in the Misawa Air Base and Kadena Air Base.[2]

The Japanese government paid ¥217 billion (US$2.0 billion) in 2007[3] as annual host-nation support called Omoiyari Yosan (思いやり予算, sympathy budget or compassion budget).[4] As of the 2011 budget, such payment was no longer to be referred to as Omoiyari Yosan or sympathy budget.[5] Japan compensates 75 percent of U.S. basing costs — $4.4 billion.[6]

The U.S. government employs over 8,000 Master Labor Contract (MLC)/Indirect Hire Agreement (IHA) workers on Okinawa (per the Labor Management Organization) not including Okinawan contract workers.[7]

Immediately after the 2011 Tōhoku earthquake and tsunami, 9,720 dependents of United States military and government civilian employees in Japan evacuated the country, mainly to the United States.[8]

The relocation of the U.S. Marine Corps Air Station Futenma to Henoko had been resolved in December 2013 with the signing of the landfill agreement by the governor of Okinawa. Under the terms of the U.S.-Japan agreement 5,000 U.S. Marines should have been relocated to Guam and 4,000 U.S. Marines to other Pacific locations such as Hawaii or Australia, while some 10,000 Marines were to remain on Okinawa.[9][10][11][12][13][14][15] No timetable for the Marines redeployment had been announced, but The Washington Post reported that U.S. Marines would leave Okinawa as soon as suitable facilities on Guam and elsewhere were ready.[12] The relocation move was expected to cost 8.6 billion US Dollars[9] and includes a $3.1bn cash commitment from Japan for the move to Guam as well as for developing joint training ranges on Guam and on Tinian and Pagan in the Commonwealth of the Northern Mariana Islands.[10] Certain parcels of land on Okinawa which have been leased for use by the American military were supposed to be turned back to Japanese control via a long-term phased return process according to the agreement.[12] These returns have been ongoing since 1972.[citation needed] However, as of July 2016, the situation has not been settled.

In May 2014, in a strategic shift by the United States to Asia and the Pacific, it was revealed the US was deploying two unarmed Global Hawk long-distance surveillance drones to Japan for surveillance missions over China and North Korea.[16]

U.S. presence debate

Do they need bases in Henoko or Futenma? Are they unnecessary? Even aside from this discussion, security is changing.—Former Japan Minister of Defense Fumio Kyuma[17]

U.S. presence on Okinawa

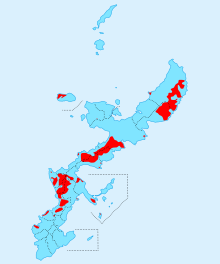

Okinawa makes up only 0.6 percent of the nation's land area;[2] yet, approximately 62% of U.S. bases in Japan (exclusive use only) are in Okinawa.[18][19]

Survey among Japanese and Okinawans

While, in 2002, 73.4% of Japanese citizens appreciate the mutual security treaty with the U.S. and the presence of the USFJ,[20][needs update] part of the population demands a reduction in the number of U.S. military bases in Okinawa.[21]

In May 2010, a survey of the Okinawan people conducted by the Mainichi Shimbun and the Ryūkyū Shimpō, found that 71% of Okinawans surveyed thought that the presence of Marines on Okinawa was not necessary (15% said it was necessary.). Asked what they thought about 62% of United States Forces Japan bases (exclusive use) being concentrated in Okinawa, 50% said that the number should be reduced, 41% said that the bases should be removed. Asked about the US-Japan security treaty, 55% said it should be changed to a peace treaty, 14% said it should be abolished and 7% said it should be maintained.[22]

Many of the bases, such as Yokota Air Base, Naval Air Facility Atsugi and Kadena Air Base, are located in the vicinity of residential districts, and local citizens have complained about excessive aircraft noise.[23][24][25] The 2014 poll by Ryūkyū Shimpō found that 80% of surveyed Okinawans want the Marine Corps Air Station Futenma moved out of the prefecture.[26]

On 25 June 2018 residents of the island of Okinawa have rallied against the construction of a new airfield intended for the US military base in the United States. The activists, armed with placards and banners, went to sea on seventy boats and ships. The posters read: “Do not build a base” and “Stop throwing gravel”. Protesters urged the Japanese authorities to stop the expansion of the US military presence on the island. Some of the boats went to the guarded construction site, where they came across the Coast Guard patrol vessels. Some activists were arrested for invading a prohibited zone.[27]

On 5 September 2018 a civic group in Okinawa demanded a local referendum on the controversial plan to relocate a key U.S. military base within the prefecture with signatures of some 93,000 people, more than four times the figure required by law. The direct request was made to Deputy Okinawa Gov Kiichiro Jahana, who took charge of the base relocation issue following the death of Gov Takeshi Onaga last month. Jahana told the group he intends to convene a prefectural assembly meeting later this month and present a proposal to hold a referendum. [28]

Status of forces agreement

There is also debate over the Status of Forces Agreement due to the fact that it covers a variety of administrative technicalities blending the systems which control how certain situations are handled between the U.S.'s and Japan's legal framework.[29]

U.S. service member behavior

Between 1972 and 2009, U.S. servicemen committed 5,634 criminal offenses, including 25 murders, 385 burglaries, 25 arsons, 127 rapes, 306 assaults and 2,827 thefts.[30] Yet, per Marine Corps Installations Pacific data, U.S. service members are convicted of far fewer crimes than local Okinawans.[31] According to the U.S.-Japan Status of Forces Agreement, when U.S. personnel crimes are committed both off-duty and off-base, they should always be prosecuted under the Japanese law.[32]

On 12 February 2008, the National Police Agency (of Japan) or NPA, released its annual criminal statistics that included activity within the Okinawan prefecture. These findings held American troops were only convicted of 53 crimes per 10,000 U.S. male servicemen, while Okinawan males were convicted of 366 crimes per 10,000. The crime rate found a U.S. serviceman in Okinawa to be 86% less likely to convicted of a crime by the Japanese government than an Okinawan male.[33]

Crime issues

At the beginning of the occupation of Japan, in 1945, many U.S. soldiers participated in the Special Comfort Facility Association.[34] The Japanese government recruited 55,000 women to work providing sexual services to US military personnel.[34] The Association was closed by the Supreme Commander for the Allied Powers.[34]

In more recent history, "crimes ranging from rape to assault and hit-and-run accidents by U.S. military personnel, dependents and civilians have long sparked protests in the prefecture," stated The Japan Times.[35] "A series of horrific crimes by present and former U.S. military personnel stationed on Okinawa has triggered dramatic moves to try to reduce the American presence on the island and in Japan as a whole," commented The Daily Beast in 2009.[36]

In 1995, the abduction and rape of a 12-year-old Okinawan schoolgirl by two U.S. marines and one U.S. sailor led to demands for the removal of all U.S. military bases in Japan. Other controversial incidents include helicopter crashes, the Girard incident, the Michael Brown Okinawa assault incident, the death of Kinjo family and the death of Yuki Uema. In February 2008, a 38-year-old U.S. Marine based on Okinawa was arrested in connection with the reported rape of a 14-year-old Okinawan girl.[37] This triggered waves of protest against American military presence in Okinawa and led to tight restrictions on off-base activities.[38][39] Although the accuser withdrew her charges the U.S. military court-martialed the suspect and sentenced him to 4 years in prison under the stricter rules of the military justice system.[40]

U.S. Forces Japan designated 22 February as a Day of Reflection for all U.S. military facilities in Japan, and established the Sexual Assault Prevention and Response Task Force in an effort to prevent similar incidents.[41] In November 2009, Staff Sgt. Clyde "Drew" Gunn, a U.S. Army soldier stationed at Torii Station was involved in a hit-and-run accident of a pedestrian in Yomitan Village on Okinawa. Later, in April 2010, the soldier was charged with failing to render aid and vehicular manslaughter.[42] Staff Sgt. Gunn, of Ocean Springs, Mississippi, was eventually sentenced to 2 years and 8 months in jail on 15 October 2010.[43]

In 2013, two U.S. military personnel, Seaman Christopher Browning, of Athens, Texas, and Petty Officer 3rd Class Skyler Dozierwalker, of Muskogee, Oklahoma, were found guilty by the Naha District Court of raping and robbing a woman in her 20s in a parking lot in October. Both admitted committing the crime. The case outraged many Okinawans, a number of whom have long complained of military-related crime on their island, which hosts thousands of U.S. troops. It also sparked tougher restrictions for all 50,000 U.S. military personnel in Japan, including a curfew and drinking restrictions.[44]

On 13 May 2013, in a very controversial statement, Toru Hashimoto, co-leader of the Japan Restoration Association said to a senior American military official at the Marine Corps base in Okinawa "We can’t control the sexual energy of these brave marines." and told United States soldiers should make more use of the local adult entertainment industry to reduce sexual crimes against local women.[45] Hashimoto also told the necessity of former Japanese Army comfort women and of prostitutes for the US military in other countries such as Korea.[45]

In June 2016, after a civilian worker at the base was charged with murdering a Japanese woman, tens of thousands of people protested in Okinawa.[46] Organizers estimated turnout at 65,000 people, which would be the largest anti-base protests in Okinawa since 1995.[47]

In November 2017, an intoxicated US service member was arrested following a vehicle crash on the Japanese island of Okinawa that killed the other driver.[48]

Osprey deployment in Okinawa

In October 2012, twelve MV-22 Ospreys were transferred to the US Marine Corps Air Station Futenma to replace aging Vietnam-era Boeing Vertol CH-46 Sea Knight helicopters in Okinawa.[49] In October 2013, an additional 12 Ospreys arrived, again to replace CH-46 Sea Knights, increasing the number of Ospreys to 24. Japanese Defence Minister Satoshi Morimoto explained the Osprey aircraft is safe adding that two recent accidents were 'caused by human factors'.[50] Japanese Prime Minister Yoshihiko Noda also stated that the Japanese government was convinced of the MV-22's safety.[51] Various incidents involving V-22 Ospreys have occurred in Okinawa.[52] On 5 April, 2018, it was announced that the US Air Force is to officially deploy CV-22 Osprey aircraft at its Yokota Air Base on the outskirts of Tokyo in a few months. The deployment would be the first of Ospreys in Japan other than in Okinawa, where the US Marines have already deployed their version of the aircraft, known as the MV-22s.[53]

On 25 April, 2018 two US Air Force Osprey MV-22, deployed at US Marine Corps Air Station Futenma on the Okinawa island, made an emergency landing at the Amami Airport on the nearby island in Kagoshima Prefecture. US Ospreys have experienced numerous mishaps in recent years, prompting Japanese officials to call for revision of certain provisions of the US-Japan Status of Forces Agreement (SOFA), which outlines the rights and privileges of foreign military personnel present in the country. [5]

Facilities

List of current facilities

The USFJ headquarters is at Yokota Air Base, about 30 km west of central Tokyo.

The U.S. military installations in Japan and their managing branches are as follows:

| Branch (MilDep) |

USFJ Facilities Admin Code |

Name of Installation | Primary Purpose (Actual) |

Location |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Air Force | FAC 1054 | Camp Chitose (Chitose III, Chitose Administration Annex) |

Communications | Chitose, Hokkaido |

| FAC 2001 | Misawa Air Base | Air Base | Misawa, Aomori | |

| FAC 3013 | Yokota Air Base | Air Base | Fussa, Tokyo | |

| FAC 3016 | Fuchu Communications Station | Communications | Fuchu, Tokyo | |

| FAC 3019 | Tama Service Annex (Tama Hills Recreation Center) |

Recreation | Inagi, Tokyo | |

| FAC 3048 | Camp Asaka (South Camp Drake AFN Transmitter Site) |

Barracks (Broadcasting) |

Wako, Saitama | |

| FAC 3049 | Tokorozawa Communications Station (Tokorozawa Transmitter Site) |

Communications | Tokorozawa, Saitama | |

| FAC 3056 | Owada Communication Site | Communications | Niiza, Saitama | |

| FAC 3162 | Yugi Communication Site | Communications | Hachioji, Tokyo | |

| FAC 4100 | Sofu Communication Site | Communications | Iwakuni, Yamaguchi | |

| FAC 5001 | Itazuke Auxiliary Airfield | Air Cargo Terminal | Hakata-ku, Fukuoka | |

| FAC 5073 | Sefurisan Liaison Annex (Seburiyama Communications Station) |

Communications | Kanzaki, Saga | |

| FAC 5091 | Tsushima Communication Site | Communications | Tsushima, Nagasaki | |

| FAC 6004 | Okuma Rest Center | Recreation | Kunigami, Okinawa | |

| FAC 6006 | Yaedake Communication Site | Communications | Motobu, Okinawa | |

| FAC 6022 | Kadena Ammunition Storage Area | Storage | Onna, Okinawa | |

| FAC 6037 | Kadena Air Base | Air Base | Kadena, Okinawa | |

| FAC 6077 | Tori Shima Range | Training | Kumejima, Okinawa | |

| FAC 6078 | Idesuna Jima Range | Training | Tonaki, Okinawa | |

| FAC 6080 | Kume Jima Range | Training | Kumejima, Okinawa | |

| Army | FAC 2070 | Shariki Communication Site | Communications | Tsugaru, Aomori |

| FAC 3004 | Akasaka Press Center (Hardy Barracks) |

Office | Minato, Tokyo | |

| FAC 3067 | Yokohama North Dock | Port Facility | Yokohama, Kanagawa | |

| FAC 3079 | Camp Zama | Office | Zama, Kanagawa | |

| FAC 3084 | Sagami General Depot | Logistics | Sagamihara, Kanagawa | |

| FAC 3102 | Sagamihara Housing Area | Housing | Sagamihara, Kanagawa | |

| FAC 4078 | Akizuki Ammunition Depot | Storage | Etajima, Hiroshima | |

| FAC 4083 | Kawakami Ammunition Depot | Storage | Higashihiroshima, Hiroshima | |

| FAC 4084 | Hiro Ammunition Depot | Storage | Kure, Hiroshima | |

| FAC 4152 | Kure Pier No.6 | Port Facility | Kure, Hiroshima | |

| FAC 4611 | Haigamine Communication Site | Communications | Kure, Hiroshima | |

| FAC 6007 | Gesaji Communication Site | Communications | Higashi, Okinawa | |

| FAC 6036 | Torii Communications Station (Torii Station) |

Communications | Yomitan, Okinawa | |

| FAC 6064 | Naha Port | Port Facility | Naha, Okinawa | |

| FAC 6076 | Army POL Depots | Storage | Uruma, Okinawa | |

| Navy | FAC 2006 | Hachinohe POL Depot | Storage | Hachinohe, Aomori |

| FAC 2012 | Misawa ATG Range (R130, Draughon Range) |

Training | Misawa, Aomori | |

| FAC 3033 | Kisarazu Auxiliary Landing Field | Air Facility | Kisarazu, Chiba | |

| FAC 3066 | Negishi Dependent Housing Area (Naval Housing Annex Negishi) |

Housing | Yokohama, Kanagawa | |

| FAC 3083 | Naval Air Facility Atsugi | Air Facility | Ayase, Kanagawa | |

| FAC 3087 | Ikego Housing Area and Navy Annex | Housing | Zushi, Kanagawa | |

| FAC 3090 | Azuma Storage Area | Storage | Yokosuka, Kanagawa | |

| FAC 3096 | Kamiseya Communications Station - returned to Japanese Gov 2015 (Naval Support Facility Kamiseya - returned to Japanese Gov 2015) |

Communications (Housing) |

Yokohama, Kanagawa | |

| FAC 3097 | Fukaya Communication Site (Naval Transmitter Station Totsuka) |

Communications | Yokohama, Kanagawa | |

| FAC 3099 | United States Fleet Activities Yokosuka | Port Facility | Yokosuka, Kanagawa | |

| FAC 3117 | Urago Ammunition Depot | Storage | Yokosuka, Kanagawa | |

| FAC 3144 | Tsurumi POL Depot | Storage | Yokohama, Kanagawa | |

| FAC 3181 | Iwo Jima Communication Site | Communications (Training) |

Ogasawara, Tokyo | |

| FAC 3185 | New Sanno U.S. Forces Center | Recreation | Minato, Tokyo | |

| FAC 5029 | United States Fleet Activities Sasebo | Port Facility | Sasebo, Nagasaki | |

| FAC 5030 | Sasebo Dry Dock Area | Port Facility | Sasebo, Nagasaki | |

| FAC 5032 | Akasaki POL Depot | Storage | Sasebo, Nagasaki | |

| FAC 5033 | Sasebo Ammunition Supply Point | Storage | Sasebo, Nagasaki | |

| FAC 5036 | Iorizaki POL Depot | Storage | Sasebo, Nagasaki | |

| FAC 5039 | Yokose POL Depot | Storage | Saikai, Nagasaki | |

| FAC 5050 | Harioshima Ammunition Storage Area | Storage | Sasebo, Nagasaki | |

| FAC 5086 | Tategami Basin Port Area | Port Facility | Sasebo, Nagasaki | |

| FAC 5118 | Sakibe Navy Annex | Hangar | Sasebo, Nagasaki | |

| FAC 5119 | Hario Dependent Housing Area (Hario Family Housing Area) |

Housing | Sasebo, Nagasaki | |

| FAC 6028 | Tengan Pier | Port Facility | Uruma, Okinawa | |

| FAC 6032 | Camp Shields | Barracks | Okinawa, Okinawa | |

| FAC 6046 | Awase Communications Station | Communications | Okinawa, Okinawa | |

| FAC 6048 | White Beach Area | Port Facility | Uruma, Okinawa | |

| FAC 6084 | Kobi Sho Range | Training | Ishigaki, Okinawa | |

| FAC 6085 | Sekibi Sho Range | Training | Ishigaki, Okinawa | |

| FAC 6088 | Oki Daito Jima Range | Training | Kitadaito, Okinawa | |

| Marine Corps |

FAC 3127 | Camp Fuji | Barracks | Gotenba, Shizuoka |

| FAC 3154 | Numazu Training Area | Training | Numazu, Shizuoka | |

| FAC 4092 | Marine Corps Air Station Iwakuni | Air Station | Iwakuni, Yamaguchi | |

| FAC 6001 | Northern Training Area (Incl. Camp Gonsalves) |

Training | Kunigami, Okinawa | |

| FAC 6005 | Ie Jima Auxiliary Airfield | Training | Ie, Okinawa | |

| FAC 6009 | Camp Schwab | Training | Nago, Okinawa | |

| FAC 6010 | Henoko Ordnance Ammunition Depot | Storage | Nago, Okinawa | |

| FAC 6011 | Camp Hansen | Training | Kin, Okinawa | |

| FAC 6019 | Kin Red Beach Training Area | Training | Kin, Okinawa | |

| FAC 6020 | Kin Blue Beach Training Area | Training | Kin, Okinawa | |

| FAC 6029 | Camp Courtney | Barracks | Uruma, Okinawa | |

| FAC 6031 | Camp McTureous | Barracks | Uruma, Okinawa | |

| FAC 6043 | Camp Kuwae (Camp Lester) | Medical Facility | Chatan, Okinawa | |

| FAC 6044 | Camp Zukeran (Camp Foster) | Barracks | Chatan, Okinawa | |

| FAC 6051 | Marine Corps Air Station Futenma | Air Station | Ginowan, Okinawa | |

| FAC 6056 | Makiminato Service Area (Camp Kinser) | Logistics | Urasoe, Okinawa | |

| FAC 6082 | Tsuken Jima Training Area | Training | Uruma, Okinawa |

- Camp Smedley D. Butler, Okinawa Prefecture, Yamaguchi Prefectures. (Although these camps are dispersed throughout Okinawa and the rest of Japan they are all under the heading of Camp Smedley D. Butler):

- Camp McTureous, Okinawa Prefecture

- Camp Courtney, Okinawa Prefecture

- Camp Foster, Okinawa Prefecture

- Camp Kinser, Okinawa Prefecture

- Camp Hansen, Okinawa Prefecture

- Camp Schwab, Okinawa Prefecture

- Camp Gonsalves (Jungle Warfare Training Center), Okinawa Prefecture

- Kin Blue Beach Training Area, Okinawa Prefecture

- Kin Red Beach Training Area, Okinawa Prefecture

- Higashionna Ammunition Storage Point II

- Henoko Ordnance Ammunition Depot

- Marine Corps Air Station Futenma, Okinawa Prefecture (return after the MCAS Futenma relocates to Camp Schwab)

- Marine Corps Air Station Iwakuni

- Camp Fuji, Shizuoka Prefecture

- Numazu Training Area, Shizuoka Prefecture

- Ie Jima Auxiliary Airfield, Okinawa Prefecture

- Tsuken Jima Training Area, Okinawa Prefecture

JSDF-USFJ Joint Use Facilities and Areas

Temporary use facilities and areas are as follows:

| USFJ Facilities Admin Code |

Name of Installation | Primary Purpose |

Location |

|---|---|---|---|

| FAC 1066 | Camp Higashi Chitose (JGSDF) | Training | Chitose, Hokkaido |

| FAC 1067 | Hokkaido Chitose Maneuver Area (JGSDF) | Training | Chitose, Hokkaido |

| FAC 1068 | Chitose Air Base (JASDF) | Air Base | Chitose, Hokkaido |

| FAC 1069 | Betsukai Yausubetsu Large Maneuver Area (JGSDF) | Training | Betsukai, Hokkaido |

| FAC 1070 | Camp Kushiro (JGSDF) | Barracks | Kushiro, Hokkaido |

| FAC 1071 | Camp Shikaoi (JGSDF) | Training | Shikaoi, Hokkaido |

| FAC 1072 | Kamifurano Medium Maneuver Area (JGSDF) | Training | Kamifurano, Hokkaido |

| FAC 1073 | Camp Sapporo (JGSDF) | Training | Sapporo, Hokkaido |

| FAC 1074 | Shikaoi Shikaribetsu Medium Maneuver Area (JGSDF) | Training | Shikaoi, Hokkaido |

| FAC 1075 | Camp Obihiro (JGSDF) | Training | Obihiro, Hokkaido |

| FAC 1076 | Asahikawa Chikabumidai Maneuver Area (JGSDF) | Training | Asahikawa, Hokkaido |

| FAC 1077 | Camp Okadama (JGSDF) | Recreation | Sapporo, Hokkaido |

| FAC 1078 | Nayoro Maneuver Area (JGSDF) | Training | Nayoro, Hokkaido |

| FAC 1079 | Takikawa Maneuver Area (JGSDF) | Training | Takikawa, Hokkaido |

| FAC 1080 | Bihoro Training Area (JGSDF) | Training | Bihoro, Hokkaido |

| FAC 1081 | Kutchan Takamine Maneuver Area (JGSDF) | Training | Kutchan, Hokkaido |

| FAC 1082 | Engaru Maneuver Area (JGSDF) | Training | Engaru, Hokkaido |

| FAC 2062 | Camp Sendai (JGSDF) | Training | Sendai, Miyagi |

| FAC 2063 | Camp Hachinohe (JGSDF) | Barracks | Hachinohe, Aomori |

| FAC 2064 | Iwate Iwatesan Medium Maneuver Area (JGSDF) | Training | Takizawa, Iwate |

| FAC 2065 | Taiwa Ojojihara Large Maneuver Area (JGSDF) | Training | Taiwa, Miyagi |

| FAC 2066 | Kasuminome Airfield (JGSDF) | Airfield | Sendai, Miyagi |

| FAC 2067 | Aomori Kotani Maneuver Area (JGSDF) | Training | Aomori, Aomori |

| FAC 2068 | Hirosaki Maneuver Area (JGSDF) | Training | Hirosaki, Aomori |

| FAC 2069 | Jinmachi Otakane Maneuver Area (JGSDF) | Training | Murayama, Yamagata |

| FAC 3104 | Nagasaka Rifle Range (JGSDF) | Training | Yokosuka, Kanagawa |

| FAC 3183 | Fuji Maneuver Area (JGSDF) | Training | Fujiyoshida, Yamanashi Gotenba, Shizuoka |

| FAC 3184 | Camp Takigahara (JGSDF) | Training | Gotenba, Shizuoka |

| FAC 3186 | Takada Sekiyama Maneuver Area (JGSDF) | Training | Joetsu, Niigata |

| FAC 3187 | Hyakuri Air Base (JASDF) | Air Base | Omitama, Ibaraki |

| FAC 3188 | Soumagahara Maneuver Area (JGSDF) | Training | Shinto, Gunma |

| FAC 3189 | Camp Asaka (JGSDF) | Training | Asaka, Saitama |

| FAC 4161 | Komatsu Air Base (JASDF) | Air Base | Komatsu, Ishikawa |

| FAC 4162 | 1st Service School (JMSDF) | Training | Etajima, Hiroshima |

| FAC 4163 | Haramura Maneuver Area (JGSDF) | Training | Higashihiroshima, Hiroshima |

| FAC 4164 | Imazu Aibano Medium Maneuver Area (JGSDF) | Training | Takashima, Shiga |

| FAC 4165 | Gifu Air Base (JASDF) | Recreation | Kakamigahara, Gifu |

| FAC 4166 | Camp Itami (JGSDF) | Training | Itami, Hyogo |

| FAC 4167 | Nihonbara Medium Maneuver Area (JGSDF) | Training | Nagi, Okayama |

| FAC 4168 | Miho Air Base (JASDF) | Air Base | Sakaiminato, Tottori |

| FAC 5115 | Nyutabaru Air Base (JASDF) | Air Base | Shintomi, Miyazaki |

| FAC 5117 | Sakibe Rifle Range (JMSDF) | Training | Sasebo, Nagasaki |

| FAC 5120 | Hijudai-Jumonjibaru Maneuver Area (JGSDF) | Training | Yufu, Oita Beppu, Oita |

| FAC 5121 | Tsuiki Air Base (JASDF) | Air Base | Chikujo, Fukuoka |

| FAC 5122 | Omura Air Base (JMSDF) | Recreation | Omura, Nagasaki |

| FAC 5123 | Oyanohara-Kirishima Maneuver Area (JGSDF) | Training | Yamato, Kumamoto Ebino, Miyazaki |

| FAC 5124 | Camp Kita Kumamoto (JGSDF) | Training | Kumamoto, Kumamoto |

| FAC 5125 | Camp Kengun (JGSDF) | Training | Kumamoto, Kumamoto |

| FAC 6181 | Ukibaru Jima Training Area | Training | Uruma, Okinawa |

In Okinawa, U.S. military installations occupy about 10.4 percent of the total land usage. Approximately 74.7 percent of all the U.S. military facilities in Japan are located on the island of Okinawa.

List of former facilities

The United States has returned some facilities to Japanese control. Some are used as military bases of the JSDF; others have become civilian airports or government offices; many are factories, office buildings or residential developments in the private sector. Due to the Special Actions Committee on Okinawa, more land in Okinawa is in the process of being returned. These areas include—Camp Kuwae [also known as Camp Lester], MCAS Futenma, areas within Camp Zukeran [also known as Camp Foster], about 9,900 acres (40 km2) of the Northern Training Area, Aha Training Area, Gimbaru Training Area (also known as Camp Gonsalves), small portion of the Makiminato Service Area (also known as Camp Kinser), and Naha Port.

Army:

- Army Composite Service Group Area (later, Chinen Service Area), Nanjō, Okinawa

- Army STRATCOM Warehouse (later, Urasoe Warehouse), Urasoe, Okinawa

- Bluff Area (later, Yamate Dependent Housing Area), Yokohama, Kanagawa

- Bolo Point Auxiliary Airfield (later, Trainfire Range), Yomitan, Okinawa

- Bolo Point Army Annex, Yomitan, Okinawa

- Camp Bender, Ōta, Gunma

- Camp Boone, Ginowan, Okinawa

- Camp Burness, Chūō, Tokyo

- Camp Chickamauga, 19th Infantry, Beppu, Oita[54]

- Camp Chigasaki, Chigasaki, Kanagawa

- Camp Chitose Annex (Chitose I, II), Chitose, Hokkaido

- Camp Coe, Yokohama, Kanagawa

- Camp Crawford, Sapporo, Hokkaido

- Camp Drake, Asaka, Saitama

- Camp Drew, Ōizumi, Gunma

- Camp Eta Jima, Etajima, Hiroshima

- Camp Fowler, Sendai, Miyagi

- Camp Fuchinobe (Office Japan, NSAPACREP), Sagamihara, Kanagawa

- Camp Hakata, Higashi-ku, Fukuoka[54]

- Camp Hardy, Ginoza, Okinawa

- Camp Haugen, Hachinohe, Aomori

- Camp Katakai, Kujūkuri, Chiba

- Camp King (later, Omiya Ordnance Sub Depot), Omiya, Saitama

- Camp Kokura, Kitakyushu, Fukuoka

- Camp Kubasaki (later, Kubasaki School Area), [Nakagusuku, Okinawa]

- Camp Loper, Tagajō, Miyagi

- Camp McGill, Yokosuka, Kanagawa

- Camp McNair, Fujiyoshida, Yamanashi

- Camp Mercy, Ginowan, Okinawa

- Camp Moore, Kawasaki, Kanagawa

- Camp Mower 34th Infantry, Sasebo, Nagasaki[54]

- Camp Nara, Nara, Nara

- Camp Ojima, Ōta, Gunma

- Camp Otsu, Ōtsu, Shiga

- Camp Palmer, Funabashi, Chiba

- Camp Schimmelpfennig, Sendai, Miyagi

- Camp Stilwell, Maebashi, Gunma

- Camp Weir, Shinto, Gunma

- Camp Whittington, Kumagaya, Saitama

- Camp Wood, 21st Infantry, Kumamoto[54]

- Camp Younghans, Higashine, Yamagata

- Chibana Army Annex (later, Chibana Site), Okinawa, Okinawa

- Chinen Army Annex (later, Chinen Site), Chinen, Okinawa

- Chuo Kogyo (later, Niikura Warehouse Area), Wako, Saitama

- Deputy Division Engineer Office, Urasoe, Okinawa

- Division School Center, Kokura[54]

- Etchujima Warehouse, Koto, Tokyo

- Funaoka Ammunition Depot, Shibata, Miyagi

- Hachinohe LST Barge Landing Area, Hachinohe, Aomori

- Hakata Transportation Office, Hakata-ku, Fukuoka

- Hamby Auxiliary Airfield, Chatan, Okinawa

- Hosono Ammunition Depot, Seika, Kyoto

- Iribaru (Nishihara) Army Annex, Uruma, Okinawa

- Ishikawa Army Annex, Uruma, Okinawa

- Japan Logistical Command (Yokohama Customs House), Yokohama, Kanagawa

- Jefferson Heights, Chiyoda, Tokyo

- Kanagawa Milk Plant, Yokohama, Kanagawa

- Kashiji Army Annex, Chatan, Okinawa

- Kishine Barracks, Yokohama, Kanagawa

- Kobe Pier No. 6, Kobe, Hyogo

- Kobe Port Building, Kobe, Hyogo

- Koza Radio Relay Annex (later, Koza Communication Site), Okinawa, Okinawa

- Kure Barge Landing Area, Kure, Hiroshima

- Lincoln Center, Chiyoda, Tokyo

- Moji Port, Kitakyushu, Fukuoka

- Nagoya Procurement (Purchasing and Contracting) Office, Nagoya, Aichi

- Naha Army Annex (later, Naha Site), Naha, Okinawa

- Naha Service Center, Naha, Okinawa

- Namihira Army Annex, Yomitan, Okinawa

- Negishi Racetrack Area, Yokohama, Kanagawa

- Okinawa Regional Exchange Cold Storage (later, Naha Cold Storage), Naha, Okinawa

- Okinawa Regional Exchange Dry Storage Warehouse (later, Makiminato Warehouse), Urasoe, Okinawa

- Onna Point Army Annex (later, Onna Site), Onna, Okinawa

- Oppama Ordnance Depot, Yokosuka, Kanagawa

- Ota Koizumi Airfield (Patton Field Air Drop Range), Oizumi, Gunma

- Palace Heights, Chiyoda, Tokyo

- Pershing Heights (Headquarters, U.S. Far East Command/United Nations Command), Shinjuku, Tokyo

- Sakuradani Rifle Range, Chikushino, Fukuoka

- Sanno Hotel Officer's Quarter, Chiyoda, Tokyo

- Shikotsuko Training Area, Chitose, Hokkaido

- Shinzato Communication Site, Nanjo, Okinawa

- South Ammunition Storage Annex (later, South Ammunition Storage Area), Yaese, Okinawa

- Sunabe Army Annex, Chatan, Okinawa

- Tana Ammunition Depot, Yokohama, Kanagawa

- Tairagawa (Deragawa) Communication Site, Uruma, Okinawa

- Tengan Communication Site, Uruma, Okinawa

- Tokyo Army Hospital, Chūō, Tokyo

- Tokyo Quartermaster Depot, Minato, Tokyo

- Tokyo Ordnance Depot (later, Camp Oji), Kita, Tokyo

- U.S. Army Medical Center, Sagamihara, Kanagawa

- U.S. Army Printing and Publication Center, Far East, Kawasaki, Kanagawa

- U.S. Army Procurement Agency, Japan, Yokohama, Kanagawa

- Yokohama Center Pier (MSTS-FE), Yokohama, Kanagawa

- Yokohama Engineering Depot, Yokohama, Kanagawa

- Yokohama Motor Command, Yokohama, Kanagawa

- Yokohama Ordnance Depot, Yokohama, Kanagawa

- Yokohama POL Depot, Yokohama, Kanagawa

- Yokohama Servicemen Club, Yokohama, Kanagawa

- Yokohama Signal Supply Depot, Kawasaki, Kanagawa

- Yokohama Signal Maintenance Depot (JLC Air Strip), Yokohama, Kanagawa

- Yokohama South Pier, Yokohama, Kanagawa

- Yomitan Army Annex, Yomitan, Okinawa

- Zama Rifle Range, Sagamihara, Kanagawa

- Zukeran Propagation Annex (later, Communication Site), Chatan, Okinawa

Navy:

- Haiki (Sasebo) Rifle Range, Sasebo, Nagasaki

- Inanba Shima Gunnery Firing Range, Mikurajima, Tokyo

- Kinugasa Ammunition Depot, Yokosuka, Kanagawa

- Koshiba POL Depot, Yokohama, Kanagawa

- Ominato Communication Site, Ominato, Aomori

- Omura Rifle Range, Omura, Nagasaki

- Makiminato Service Area Annex, Urasoe, Okinawa

- Minamitorishima Communication Site, Ogasawara, Tokyo

- Nagahama Rifle Range, Kure, Hiroshima

- Nagai Dependent Housing Area (Admiralty Heights), Yokosuka, Kanagawa

- Nagiridani Dependent Housing Area, Sasebo, Nagasaki

- Naval Air Facility Naha, Naha, Okinawa

- Naval Air Facility Oppama, Yokosuka, Kanagawa

- Navy EM Club, Yokosuka, Yokosuka, Kanagawa

- Niigata Sekiya Communication Site, Chuo-ku, Niigata

- Shinyamashita Dependent Housing Area (Bayside Court), Yokohama, Kanagawa

- Sobe Communication Site (NSGA Hanza), Yomitan, Okinawa

- Tokachibuto Communication Site, Urahoro, Hokkaido

- Tomioka Storage Area, Yokohama, Kanagawa

- Tsujido Maneuver Area, Chigasaki, Kanagawa

- Yokohama Bakery, Yokohama, Kanagawa

- Yokohama Beach (Honmoku) Dependent Housing Area, Yokohama, Kanagawa

- Yokohama Chapel Center, Yokohama, Kanagawa

- Yokohama Cold Storage, Yokohama, Kanagawa

- Yokosuka Naval Pier, Yokosuka, Kanagawa

- Yosami Communication Site, Kariya, Aichi

Air Force:

- Ashiya Air Base (later, ATG Range), Ashiya, Fukuoka

- Asoiwayama Liaison Annex, Tobetsu, Hokkaido

- Brady Air Base (later, Gannosu Air Station), Higashi-ku, Fukuoka

- Chiran Communication Site, Chiran, Kagoshima

- Chitose Air Base, Chitose, Hokkaido

- Daikanyama Communication Site, Yugawara, Kanagawa

- Fuchu Air Station (Headquarters, USFJ/Fifth Air Force, 1957–1974), Fuchu, Tokyo

- Funabashi Communication Site, Funabashi, Chiba

- Grant Heights Dependent Housing Area, Nerima, Tokyo

- Green Park Housing Annex, Musashino, Tokyo

- Hachinohe Small Arms Range, Hachinohe, Aomori

- Hamura School Annex, Hamura, Tokyo

- Haneda Air Base (later, Postal Service Annex), Ota, Tokyo

- Hanshin Auxiliary Airfield, Yao, Osaka

- Hirao Communication Site, Chuo-ku, Fukuoka

- Itami Air Base, Itami, Hyogo

- Itazuke Administration Annex (Kasugabaru DHA), Kasuga, Fukuoka

- Itazuke Air Base, Hakata-ku, Fukuoka

- Johnson Air Base (later, Air Station, Family Housing Annex), Iruma, Saitama

- Kadena Dependent Housing Area, Yomitan, Okinawa

- Kanto Mura Dependent Housing Area and Auxiliary Airfield, Chofu, Tokyo

- Kasatoriyama Radar Site, Tsu, Mie

- Kashiwa Communication Site (Camp Tomlinson), Kashiwa, Chiba

- Komaki (Nagoya) Air Base, Komaki, Aichi

- Kozoji Ammunition Depot, Kasugai, Aichi

- Kume Jima Air Station, Kumejima, Okinawa

- Kushimoto Radar Site, Kushimoto, Wakayama

- Miho Air Base, Sakaiminato, Tottori

- Mineoka Liaison Annex, Minamiboso, Chiba

- Mito ATG Range, Hitachinaka, Ibaraki

- Miyako Jima Air Station, Miyakojima, Okinawa

- Miyako Jima VORTAC Site, Miyakojima, Okinawa

- Moriyama Air Station, Nagoya, Aichi

- Naha Air Base, Naha, Okinawa

- Naha Air Force/Navy Annex, Naha, Okinawa

- Najima Warehouse Area, Higashi-ku, Fukuoka

- Niigata Air Base, Niigata, Niigata

- Ofuna Warehouse, Yokohama, Kanagawa

- Oshima Communication Center, Oshima, Tokyo

- Rokko Communication Site, Kobe, Hyogo

- Senaha Communications Station, Yomitan, Okinawa (returned to the Japanese government in September 2006)

- Sendai Kunimi Communication Site, Sendai, Miyagi

- Showa (later, Akishima) Dependent Housing Area, Akishima, Tokyo

- Shiroi Air Base, Kashiwa, Chiba

- Sunabe Warehouse, Chatan, Okinawa

- Tachikawa Air Base, Tachikawa, Tokyo

- Tokyo Communication Site (NTTPC Central Telephone Exchange), Chūō, Tokyo

- Wajima Liaison Annex, Wajima, Ishikawa

- Wajiro Water Supply Site, Higashi-ku, Fukuoka

- Wakkanai Air Station, Wakkanai, Hokkaido

- Washington Heights Dependent Housing Area, Shibuya, Tokyo

- Yamada Ammunition Depot, Kitakyushu, Fukuoka

- Yokawame Communication Site, Misawa, Aomori

- Yozadake Air Station, Itoman, Okinawa

Marines:

- Aha Training Area, Kunigami, Okinawa

- Camp Gifu, Kakamigahara, Gifu

- Camp Hauge, Uruma, Okinawa

- Camp Okubo, Uji, Kyoto

- Camp Shinodayama, Izumi, Osaka

- Gimbaru Training Area, Kin, Okinawa

- Ihajo Kanko Hotel, Uruma, Okinawa

- Makiminato Housing Area, Naha, Okinawa

- Onna Communication Site, Onna, Okinawa

- Awase Golf Course, Okinawa Prefecture (returned to the Japanese government in April 2010)

- Yaka Rest Center, Kin, Okinawa

- Yomitan Auxiliary Airfield, Yomitan, Okinawa (returned to the Japanese government in 2006, parachute drop training ended in March 2001)

See also

- United States Forces Korea (USFK)

- United States Military Government of the Ryukyu Islands

- United States Civil Administration of the Ryukyu Islands

- Operation Tomodachi

- Bell Boeing V-22 Osprey

References

- ^ 疑惑が晴れるのはいつか, Okinawa Times, 16 May 1999

- ^ a b Yoshida, Reiji, "Basics of the U.S. military presence", Japan Times, 25 March 2008, p. 3.

- ^ 思いやり予算8億円減で日米合意、光熱水料を3年間で, Yomiuri Shinbun, 12 December 2007

- ^ PRESS RELEASE U.S. and Japan Sign Alliance Support Agreement Archived 27 January 2011 at the Wayback Machine, The embassy of the United States in Japan

- ^ http://www.japantimes.co.jp/news/2011/01/22/national/host-nation-deal-inked-not-sympathy-budget/#.WAOBmCRbTGs

- ^ Zeynalov, Mahir (25 December 2017). "Defending Allies: Here is how much US Gains from Policing World". The Globe Post. Retrieved 10 May 2018.

- ^ "Purpose and Duties". Labor Management Organization. Retrieved 10 March 2012.

- ^ Tritten, Travis J., "Evacuation from Japan a vacation? Not so much", Stars and Stripes, 31 May 2011.

- ^ a b Seales, Rebecca (27 April 2012). "End of an era: U.S. cuts back presence in Okinawa as 9,000 Marines prepare to move out". Daily Mail. London. Retrieved 27 April 2012.

- ^ a b "US agrees to Okinawa troop redeployment". Al Jazeera. 27 April 2012. Retrieved 27 April 2012.

- ^ Shanker, Thom (26 April 2012). "U.S. Agrees to Reduce Size of Force on Okinawa". The New York Times. Retrieved 27 April 2012.

- ^ a b c Greg Jaffe and Emily Heil (27 April 2012). "U.S. comes to agreement with Japan to move 9,000 Marines off Okinawa". The Washington Post. Retrieved 27 April 2012.

- ^ "Okinawa deal between US and Japan to move marines". BBC. 27 April 2012. Retrieved 27 April 2012.

- ^ "U.S., Japan unveil revised plan for Okinawa". The Asahi Shimbun. 27 April 2012. Archived from the original on 30 April 2012. Retrieved 27 April 2012.

{{cite news}}: Unknown parameter|dead-url=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ Quintana, Miguel (28 April 2012). "Japan Welcomes US Base Agreement". Voice of America. Retrieved 28 April 2012.

- ^ "Advanced US drones deployed in Japan to keep watch on China, North Korea". The Japan News.Net. Retrieved 31 May 2014.

{{cite news}}: Italic or bold markup not allowed in:|publisher=(help) - ^ http://english.ryukyushimpo.jp/2018/02/16/28494/

- ^ [1] Archived 4 March 2014 at the Wayback Machine, Okinawa Prefectural Government

- ^ http://www.asahi.com/ajw/articles/AJ201606290073.html

- ^ "自衛隊・防衛問題に関する世論調査". The Cabinet Office of Japan. 2002. Archived from the original on 22 October 2010.

- ^ "Japanese protest against US base". BBC News. 8 November 2009.

- ^ "毎日世論調査:辺野古移設に反対84% 沖縄県民対象". Megalodon.jp. Retrieved 10 March 2012.

- ^ 基地騒音の問題 Archived 4 March 2008 at the Wayback Machine, Yamato City

- ^ 横田基地における騒音防止対策の徹底について(要請) Archived 24 February 2009 at the Wayback Machine, Tokyo Metropolitan Government

- ^ 嘉手納町の概要 Archived 30 September 2008 at the Wayback Machine, Kadena Town

- ^ Isabel Reynolds; Takashi Hirokawa (17 November 2014). "Opponent of U.S. Base Wins Okinawa Vote in Setback for Abe". Bloomberg. Retrieved 9 February 2017.

- ^ "Protest held at sea in Okinawa against land reclamation work for U.S. Marine Corps' Futenma base". japantimes.co.jp. 25 June 2018.

- ^ "Okinawa residents seek U.S. base referendum with 93,000 signatures". japantoday.com. 6 September 2018.

- ^ "New Okinawa minister says Japan-U.S. SOFA should be 're-examined' after Osprey crash". The Japan Times Online. 9 August 2017. ISSN 0447-5763. Retrieved 14 January 2018.

- ^ Hearst, David (7 March 2011). "Second battle of Okinawa looms as China's naval ambition grows". the Guardian. Retrieved 20 May 2018.

- ^ [2], Ethos Data

- ^ [3], SOFA Agreement

- ^ "在日米軍・沖縄駐留米軍の犯罪率を考える - 駄犬日誌". D.hatena.ne.jp. 14 February 2008. Retrieved 10 March 2012.

- ^ a b c KRISTOF, NICHOLAS (27 October 1995). "Fearing G.I. Occupiers, Japan Urgesd Women Into Brothels". New York Times. Retrieved 14 May 2013.

- ^ http://www.japantimes.co.jp/news/2016/06/26/national/crime-legal/u-s-civilian-arrested-fresh-okinawa-dui-case-man-injured/#.V54kfSOLTZs

- ^ http://www.thedailybeast.com/articles/2016/06/08/the-suitcase-murder-tearing-the-u-s-and-japan-apart.html

- ^ Lah, Kyung (10 February 2008). "U.S. Marine accused of raping teen in Okinawa". CNN.

- ^ "Japanese protest against US base". Al Jazeera. 23 March 2008.

- ^ "Curfew for US troops in Okinawa". BBC. 20 February 2008.

- ^ http://www.newser.com/story/27674/okinawa-marine-gets-4-years-for-teen-sex-abuse.html

- ^ U.S. imposes curfew on Okinawa forces, The Japan Times, 21 February 2008

- ^ [4][dead link]

- ^ David Allen. "U.S. soldier sentenced to Japanese jail for hit-and-run on Okinawa - News". Stripes. Retrieved 10 March 2012.

- ^ "U.S. Navy sailors convicted in Okinawa rape". USA Today. Retrieved 19 March 2013.

- ^ a b Tabuchi, Hiroko (13 May 2013). "Women Forced Into WWII Brothels Served Necessary Role, Osaka Mayor Says". New York Times. Retrieved 14 May 2013.

- ^ Ben Westcott, Japanese woman's murder provokes protests against U.S. bases in Okinawa, CNN (June 20, 2016).

- ^ Jonathan Soble, At Okinawa Protest, Thousands Call for Removal of U.S. Bases, New York Times (June 19, 2016).

- ^ http://edition.cnn.com/2017/11/19/asia/okinawa-american-drunk-driver/

- ^ 英語学習サイト. "| 社説 | 英語のニュース | The Japan Times ST オンライン ― 英字新聞社ジャパンタイムズの英語学習サイト". st.japantimes.co.jp (in Japanese). Retrieved 14 January 2018.

- ^ "US Osprey military aircraft begin Okinawa base move". BBC News. 1 October 2012.

- ^ "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 8 October 2012. Retrieved 4 October 2012.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|dead-url=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help)CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link) - ^ "Osprey - The Japan Times". The Japan Times. Retrieved 14 January 2018.

- ^ "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 11 April 2018. Retrieved 11 April 2018.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|dead-url=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help)CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link) - ^ a b c d e A Soldier in Kyushu Archived 14 May 2008 at the Wayback Machine, By Capt. William B. Koons, 1 October 1947

External links

- United States Forces Japan

- U.S. Naval Forces Japan

- U.S. Forces, Japan (GlobalSecurity.org)

- Overseas Presence: Issues Involved in Reducing the Impact of the U.S. Military Presence on Okinawa, GAO, March 1998

- U.S. Military Issues in Okinawa

- LMO